Abstract

Background

Women of reproductive age in parts of sub-Saharan Africa are faced both with high levels of HIV and the threat of dying from the direct complications of pregnancy. Clinicians practicing in such settings have reported a high incidence of direct obstetric complications among HIV-infected women, but the evidence supporting this is unclear. The aim of this systematic review is to establish whether HIV-infected women are at increased risk of direct obstetric complications.

Methods and findings

Studies comparing the frequency of obstetric haemorrhage, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, dystocia and intrauterine infections in HIV-infected and uninfected women were identified. Summary estimates of the odds ratio (OR) for the association between HIV and each obstetric complication were calculated through meta-analyses. In total, 44 studies were included providing 66 data sets; 17 on haemorrhage, 19 on hypertensive disorders, five on dystocia and 25 on intrauterine infections. Meta-analysis of the OR from studies including vaginal deliveries indicated that HIV-infected women had over three times the risk of a puerperal sepsis compared with HIV-uninfected women [pooled OR: 3.43, 95% confidence interval (CI): 2.00–5.85]; this figure increased to nearly six amongst studies only including women who delivered by caesarean (pooled OR: 5.81, 95% CI: 2.42–13.97). For other obstetric complications the evidence was weak and inconsistent.

Conclusions

The higher risk of intrauterine infections in HIV-infected pregnant and postpartum women may require targeted strategies involving the prophylactic use of antibiotics during labour. However, as the huge excess of pregnancy-related mortality in HIV-infected women is unlikely to be due to a higher risk of direct obstetric complications, reducing this mortality will require non obstetric interventions involving access to ART in both pregnant and non-pregnant women.

Introduction

The substantial burden of HIV infection amongst women of reproductive age in sub-Saharan Africa and the maternal health risks that these women are challenged with has lead to HIV and maternal mortality being described as two intersecting epidemics [1], [2]. Many pregnant women in this region face not only the threat of dying from the direct complications of pregnancy and delivery, but also from complications arising from advancing HIV disease. Given this intersection, it is important to understand whether and how HIV interacts with pregnancy.

The biological interaction between HIV and pregnancy is not well understood. It has been argued that pregnancy may accelerate HIV progression as pregnancy is associated with suppressed immune function independent of HIV status [3], [4]. However, the epidemiological evidence supporting this hypothesis is weak. A systematic review investigating the effects of pregnancy on HIV progression and survival found no evidence that pregnancy increased progression to an HIV-related illness or a fall in CD4 count to fewer than 200 cells per cubic millilitre. The same review showed weak evidence that pregnant women were more likely to progress to an AIDS-defining illness or death compared with their non-pregnant counterparts but this was based on only six studies [5].

Clinicians working in settings where HIV is highly prevalent have reported a high incidence of direct obstetric complications in HIV-infected pregnant women [6]. Some researchers have also hypothesised that HIV may increase the risk of direct obstetric complications, though the evidence was based on very few studies with small sample sizes [2], [7]. There are several biological pathways which may explain such an association. Firstly, the compromised immune status and general poor health of HIV-infected women may leave them more vulnerable to infections, including puerperal sepsis [8]. Secondly, it has been suggested that HIV-related thrombocytopenia, where there is a low platelet count in the blood, may increase a woman's risk of haemorrhage [9]. Additionally, social factors such as poor access to healthcare increase a woman's risk of obstetric complications, and may be exacerbated in HIV-infected women due to the discrimination and stigma these women face in some settings [10].

To date there has been no effort to synthesise the empirical evidence on the association between HIV and direct obstetric complications. The aim of this study is to investigate whether HIV increases the risk of obstetric complications, by systematically reviewing literature which compares the risk of obstetric complications in HIV-infected and uninfected women. The obstetric complications which were pre-specified for this review are obstetric haemorrhage, pregnancy-induced hypertension, dystocia and intrauterine infections.

Methods

Search Strategy

Pubmed, Embase, Popline and African Index Medicus were searched up to 6th July 2011 using search terms for HIV, pregnancy and the following direct obstetric complications: obstetric haemorrhage, pregnancy-induced hypertension, dystocia and intrauterine infections (see Supplementary File S1 for the full search strategy). There were no language or publication date restrictions. All abstracts were reviewed by a single author (CC) and a 20% sample of abstracts was independently reviewed by a second researcher. Full text copies of potentially relevant papers were obtained and the reference lists of review articles and articles which were included in this systematic review were searched for further relevant publications.

Eligibility Criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they compared the occurrence of direct obstetric complications during pregnancy, delivery and/or up to 365 days postpartum between HIV-infected and uninfected women using a cohort, cross-sectional or case-control design. Obstetric complications relevant for this review were categorised as: obstetric haemorrhage (including placenta praevia, placental abruption, antepartum haemorrhage, peri- or postpartum haemorrhage and retained placenta); pregnancy-induced hypertension (including eclampsia and pre-eclampsia); dystocia (including prolonged or obstructed labour, abnormal presentation and uterine rupture); and intrauterine infections (including puerperal sepsis, wound infection and endometritis). Studies were required to have a sample size of at least 30 women in each study group with no restrictions on country, dates or whether the study was population or facility based.

Data Extraction and management

Data were extracted by a single author (CC) on: study location, dates, design and population, definition and ascertainment of the obstetrical outcome (e.g. whether haemorrhage was ascertained through visual estimate or actual measurement of blood loss), the mode of delivery, gestational age at recruitment and length of postpartum follow-up, HIV prevalence in the study population, whether antiretroviral therapy (ART) was available, the number of women with the obstetric complication by HIV status, the type of denominator (pregnancy, live births or women) and the denominator.

Study populations described in more than one paper were included only once, using data from the paper with the most detailed information. When more than one obstetrical outcome was evaluated in a single study, these were extracted and treated as separate data sets.

Assessment of risk of bias

The risk of bias for each data set was assessed using the component approach adopted by The Cochrane Collaboration [11]. All data sets were assessed on the definition and ascertainment of the obstetric complication, the completeness of data, adjustment for confounding and selection of the comparison group. Each of the quality criteria were classified as having a low risk or high risk of bias for each data set. For example, a data set was classified as having a high risk of bias for outcome ascertainment if methods which were likely to lead to cases being missed were used (e.g. hospital record review). Where there was insufficient information to assess the risk of bias, the data set was classified as at an unclear risk of generating bias.

Statistical Methods

All analyses were carried out using STATA 12.0. The association between HIV and each obstetric complication was estimated using odds ratios (OR). Summary measures of effect for each obstetric complication were obtained by conducting a random-effects meta-analysis of the best effect estimate available from each study. Where an adjusted OR was available from the paper, this was taken as the best estimate; otherwise the crude estimate was used. Articles do not generally state whether there is overlap between categories of obstetric complications, for example, whether the women who have puerperal sepsis are also the women who are included as having endometritis. We therefore only provide summary estimates for sub-categories within each broad obstetric grouping. As the effect of HIV on the obstetric complications may vary by the mode of delivery, studies which included either vaginal deliveries only or both vaginal and caesarean deliveries were considered separately from studies which only included caesareans. Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots and was formally tested using Begg's test [12].

Additionally, for data sets which included vaginal and caesarean section deliveries, a meta-analysis was conducted to assess whether HIV-infected women had increased odds of caesarean. ORs were computed for each study rather than each data set.

Results

Search Strategy Results

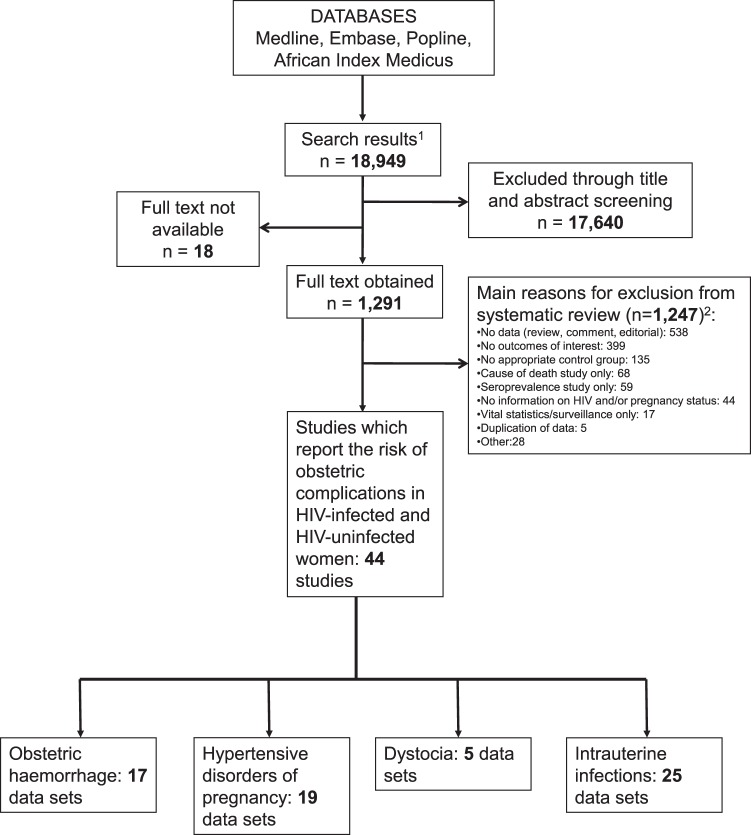

We initially identified 18,949 titles and abstracts and 1,291 of these were retained for full text review (Figure 1). Of the 1,291 articles, 1,247 were excluded as they did not contain relevant data. A total of 44 studies, providing 66 data sets, were included. Seventeen data sets contained information on obstetric haemorrhage (one caesarean only study), 19 on hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (one caesarean only study), five on dystocia and 25 data sets contained information on intrauterine infections (12 caesarean only studies and one study which was stratified by mode of delivery and therefore provided two data sets).

Figure 1. Flow chart of study selection for inclusion in the systematic review.

1After removal of duplicates 2Articles may have been excluded for multiple reasons.

Study Characteristics

Table 1 describes the 51 eligible data sets based on vaginal deliveries or all modes of delivery. The 15 data sets which only included women undergoing a caesarean section are described in Table 2. Overall, study populations were from Spain, [13]–[15] France, [16] the UK, [17] Germany, [18] Holland, [19] Italy, [20] the USA, [21]–[27] Mexico, [28] Dominican Republic, [29] Brazil, [30], [31] Kenya, [32]–[35], Ethiopia, [36] Rwanda, [37], [38] Uganda, [39]–[41] Nigeria, [42]–[44] Zimbabwe, [45] South Africa, [46]–[50] India, [51], [52] and Thailand [53], [54]. One study was conducted in Italy, Spain, Sweden, Poland and Ukraine [55] and another was conducted in Malawi, Tanzania and Zambia [56]. All studies were conducted in health facilities. Thirty-four of the data sets (52%) were conducted when ART was available in the study population.

Table 1. Summary of studies of HIV and obstetric complications which included births by vaginal delivery.

| Reference | Study design | Study Setting | Study Population | Mode of delivery in each study group | ART Available | Definition of obstetric complication | % of HIV positive with obstetric complication (total number of HIV+ women) | % of HIV negative with obstetric complication (total number of HIV+ women) | Crude Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted Odds Ratio(95% CI) | ||

| Haemorrhage | ||||||||||||

| Aboud et al. 2009 [56] | Prospective Cohort [from a randomised controlled trial (RCT)] | Multiple hospitals and antenatal clinics in Malawi (Blantyre and Lilongwe), Tanzania (Dar es Salaam) and Zambia (Lusaka) (2001–2003) | All HIV+ women enrolled and one HIV− woman enrolled for every five HIV+ women. | No information provided | No | Antepartum haemorrhage (no further details) | 0.5 (1,558) | 0 (271) | 2.98 (0.17–51.72) | - | ||

| Postpartum haemorrhage (no further details) | 0.6 (1,558) | 0 (271) | 3.68 (0.22–63.02) | - | ||||||||

| Azira et al. , 2010 [16] | Retrospective Cohort | One maternity hospital in Paris, France (2001–2006) | All HIV+ women with an undetectable viral load at 36 weeks gestation and one HIV− control for each HIV+ woman matched for parity, previous c-section and geographic origin. Excluded deliveries before 37th week of gestation, multiple pregnancies, non cephalic presentation or elective c-section and for HIV+ women viral load had to be undetectable. | HIV+: 17.8% had a c-section HIV−: 15.7% had a c-section | Yes | Postpartum haemorrhage defined as blood loss≥500mL after delivery | 12.3 (146) | 18.5 (146) | 0.62 (0.32–1.18) | - | ||

| Braddick et al., 1990 [32] | Prospective Cohort | One maternity hospital in Nairobi, Kenya (1986–1989) | All HIV+ women and HIV− women who lived close to the follow-up clinic. | HIV+: 0.5% had a c-section HIV−: No c-sections | No | Antepartum haemorrhage defined as bleeding during the third trimester | 8.1 (161) | 2.9 (307) | 2.91 (1.22–6.96) | - | ||

| Chamiso, 1996 [36] | Prospective Cohort | One maternity hospital in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (1993–1995) | All HIV+ women and HIV− women matched to the HIV+ women for age and parity. | HIV+: 6.5% had a c-section HIV−: 9.2% had a c-section | No | Placenta praevia (no further details) | 2.2 (92) | 2.9 (173) | 0.75 (0.14–3.93) | - | ||

| Postpartum haemorrhage (no further details) | 0 (92) | 1.2(173) | 0.37 (0.02–7.81) | - | ||||||||

| Retained placenta (no further details) | 0 (92) | 1.7 (173) | 0.26 (0.01–5.15) | - | ||||||||

| Chanrachakul et al., 2001 [53] | Retrospective Cohort | One tertiary hospital in Bangkok, Thailand (1991–1999) | All nulliparous HIV+ women delivering from 1991–1999 and all non-private, nulliparous HIV− women admitted in 1998. Excluded emergency c-section, deliveries before 37th week of gestation, multiple pregnancies or non cephalic presentation. | HIV+: 14.6% had a c-section HIV−: 15.0% had a c-section; analysis restricted to vaginal deliveries | No1 | Postpartum haemorrhage (no further details) | 7.3 (82) | 2.8 (1,540) | 2.75 (1.13–6.66) | - | ||

| Retained placenta (no further details) | 1.2 (82) | 0.7 (1,540) | 1.89 (0.24–14.94) | - | ||||||||

| De Groot et al., 2003 [46] | Retrospective Cohort | One high risk obstetric unit in Bloemfontein, South Africa (2001) | All HIV+ women and two HIV- controls for every HIV+ woman enrolled. | HIV+: 56.8% had a c-section HIV−: 55.7% had a c-section | No1 | Antepartum haemorrhage defined as any bleeding occurring during pregnancy but before delivery | 13.6 (81) | 8.2 (170) | 1.75 (0.76–4.05) | - | ||

| Postpartum haemorrhage defined as a fall in Hb level≥3g/dL associated with vaginal bleeding | 4.9 (81) | 6.5 (170) | 0.75 (0.23–2.43) | - | ||||||||

| Figueroa-Damian, 1999 [28] | Prospective Cohort | Institute of Perinatology in Mexico City, Mexico (1989–1997) | 44 HIV+ women and two HIV− controls for each HIV+ woman, matched on age and socioeconomic status. | HIV+: 29.9% had a c-section HIV−: 51.2% had a c-section | Yes | Postpartum haemorrhage (no further details) | 2–.3 (44) | 0 (88) | 6.10 (0.24–152.93) | - | ||

| Haeri et al., 2009 [21] | Retrospective Cohort | Two tertiary care centres in Columbia and North Carolina, USA (2000–2007) | All HIV+ women on ART and two HIV− controls for each HIV+ woman matched for age, race, parity, care location, delivery mode, insurance type and year of delivery. Excluded deliveries before 20 weeks gestation. | HIV+: 51.0% had a c-section HIV−: 52.0% had a c-section | Yes | Placental Abruption (no further details) | 1.3 (151) | 1.7 (302) | 0.80 (0.15–4.16) | - | ||

| Kourtis et al., 2006 [22] | Retrospective Cohort | 20% of all community hospitals in the USA (1994 & 2003) | All HIV+ and HIV− pregnant women between 15-44 years of age who were hospitalised. | No information provided | Yes | Antepartum haemorrhage defined according to ICD-9 codes | 2.8 (12,378) | 1.2 (8,784,767) | 2.33 (2.09–2.59) | - | ||

| Leroy et al ., 1998 [37] | Prospective Cohort | One tertiary hospital in Kigali, Rwanda (1992–1993) | All HIV+ women and one HIV− control for each HIV+ woman matched for age. Only included women resident in Kigali who attended antenatal clinic two days a week and wished to deliver in the hospital. | HIV+: 5.8% had a c-section HIV−: 6.0% had a c-section | No | Postpartum haemorrhage (no further details) | 1.4 (364) | 0 (365) | 11.18 (0.62–202.99) | - | ||

| Retained placenta (no further details) | 12.1 (305) | 10.1 (308) | 1.23 (0.74–2.05) | - | ||||||||

| Lionel et al ., 2008 [51] | Retrospective Cohort | One hospital in Vellore, India (2000–2002) | All HIV+ and HIV− women. | HIV+: 58.7% had a c-section HIV−: 21.5% had a c-section | Yes | Major placenta praevia | 0.9 (109) | 0.5 (23,277) | 2.06 (0.29–14.92) | - | ||

| Placental abruption (Grade III) | 0.9 (109) | 0.1 (23,277) | 19.58 (2.51–153.02) | - | ||||||||

| Postpartum haemorrhage (no further details) | 0 (109) | 1.2 (23,277) | 0.39 (0.02–6.31) | - | ||||||||

| Louis et al., 2006 [23] | Retrospective Cohort | One tertiary hospital in Detroit, USA (2000–2005) | All HIV+ women and a random selection of HIV− women. | HIV+: 39.9% had a c-section HIV−: 15.8% had a c-section | Yes | Postpartum haemorrhage (no further details) | 1.4 (148) | 5.3 (152) | 0.25 (0.05–1.18) | - | ||

| Minkoff et al., 1990 [24] | Prospective Cohort | Four prenatal clinics in New York, USA (1985–1989) | All HIV+ women who had a live, singleton birth; in three of the prenatal clinics all HIV− women were also recruited, and in one of the clinics two HIV− controls were selected for each HIV+ woman. | HIV+: 12.0% had a c-section HIV−: 18.0% had a c-section | No | Placenta praevia (no further details) | 1.2 (85) | 1.7 (118) | 0.69 (0.06–7.74) | - | ||

| Placental abruption (no further details) | 0 (85) | 2.5 (118) | 0.18 (0.01–3.62) | - | ||||||||

| Peripartum haemorrhage (no further details) | 4.5 (89) | 4.0 (126) | 1.14 (0.30–4.37) | - | ||||||||

| Retained placenta (no further details) | 3.4 (89) | 0.8 (126) | 4.36 (0.45–42.62) | - | ||||||||

| Mmiro et al ., 1993 [39] | Prospective Cohort | One university hospital in Kampala, Uganda (1988–1990) | All HIV+ women and a random 10% sample of HIV− women. Only included women who lived within 15km of Mulago and agreed to deliver in the hospital. | No difference in the mode of delivery in HIV+ and HIV− women | No | Antepartum haemorrhage (no further details) | 0.9 (539) | 1.4 (660) | 0.68 (0.23–2.03) | – | ||

| Postpartum haemorrhage (no further details) | 0.6 (539) | 0.9 (660) | 0.61 (0.15–2.45) | - | ||||||||

| Peret et al ., 1993 [30] | Prospective Cohort | One maternity hospital in Belo Horizonte, Brazil (2001–2003) | 82 HIV+ women and 123 HIV− women matched on mode of delivery, gestational age at delivery and maternal age. Only included women if they did not have chronic diseases and/or complications of pregnancy. | HIV+: 72.0% had a c-section HIV−: 72.0% had a c-section | Yes | Postpartum haemorrhage defined by clinical observation and/or need for at least one of the following interventions: uterotonic drugs, revision of the uterine cavity and the birth canal or curettage | 2.4 (82) | 0 (123) | 7.67 (0.36–161.86) | - | ||

| Van Eijk et al. , 2007 [33] | Prospective Cohort | One large hospital in Kisumu, Kenya (1996–2000) | All women who delivered at the hospital if they had an uncomplicated singleton pregnancy at more than 32 weeks gestation, resided in Kisumu and had no underlying chronic illnesses. | HIV+: 3.1% had a c-section HIV−: 3.6% had a c-section | Not clear | Peripartum haemorrhage (no further details) | 1.4 (743) | 0.3 (2,365) | 4.02 (1.58–2.33) | - | ||

| Hypertensive diseases of pregnancy | ||||||||||||

| Aboud et al. 2009 [56] | Prospective Cohort (from an RCT) | Multiple hospitals and antenatal clinics in Malawi (Blantyre and Lilongwe), Tanzania (Dar es Salaam) and Zambia (Lusaka) (2001–2003) | All HIV+ women enrolled and one HIV− woman enrolled for every five HIV+ women. | No information provided | No | Hypertension, with or without proteinuria, measured in the intrapartum period | 1.7 (1,558) | 1.1 (271) | 1.52 (0.46–5.04) | - | ||

| Bodkin et al., 2005 [47] | Retrospective cohort | One tertiary hospital in Gautang, South Africa (2003) | A sample of HIV+ women selected using stratified random sampling (stratifying on normal risk, moderate risk or high risk pregnancy) and one HIV− control selected for every two HIV+ women. | Only follows up women in ante-partum period | Yes | Pregnancy-induced hypertension (no further details) | 17.0 (212) | 9.9 (101) | 1.86 (0.88–3.92) | - | ||

| Eclampsia ( no further details) | 2.8 (212) | 1.0 (101) | 2.91 (0.35–24.52) | - | ||||||||

| Boer et al., 2006 [19] | Retrospective cohort | Two medical centres in Amsterdam and Rotterdam, Holland (1997–2003) | All HIV+ treated with ART and two HIV− controls for each HIV+ woman matched on maternal age, parity, ethnicity, and being singleton or twin. The controls had to be healthy and not referred, not have had obstetric complications in the past and live near the hospital. | HIV+: 40.8% had a c-section HIV−: 12.8% had a c-section | Yes | Pre-eclampsia (during pregnancy until seven days postpartum) defined according to the definition of the International Society for the Studies of Hypertension in Pregnancy | 2.0 (98) | 1.0 (196) | 2.02 (0.28–14.57) | - | ||

| Chamiso, 1996 [36] | Prospective Cohort | One maternity hospital in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (1993–1995) | All HIV+ women and HIV− women matched to the HIV+ women for age and parity. | HIV+: 6.5% had a c-section HIV−: 9.2% had a c-section | No | Pregnancy-induced hypertension defined as an increment in systolic blood pressure of 30 mmHg and in diastolic blood pressure of 15 mmHg from the pre- or early pregnancy level of blood pressure | 6.5 (92) | 2.3 (173) | 2.95 (0.81–10.72) | - | ||

| De Groot et al. , 2003 [46] | Retrospective Cohort | One high risk obstetric unit in Bloemfontein, South Africa (2001) | All HIV+ women and two HIV− controls for every HIV+ woman enrolled. | HIV+: 56.8% had a c-section HIV−: 55.7% had a c-section | No1 | Pre-eclampsia defined as systolic blood pressure of ≥140 mm Hg or a diastolic blood pressure of ≥ 90 mmHg, on at least 2 occasions 4 hours or more apart and proteinuria of ≥ 0.3 g/24 hours) | 43.2 (81) | 35.9 (170) | 1.36 (0.79–2.33) | - | ||

| Eclampsia defined as 1+ convulsions which could not be explained by other cerebral conditions, in a patient with pre-eclampsia | 7.4 (81) | 17.1 (170) | 0.39 (0.15–0.98) | - | ||||||||

| Figueroa-Damian, 1999 [28] | Prospective Cohort | Institute of Perinatology in Mexico City, Mexico (1989–1997) | 44 HIV+ women and two HIV− controls for each HIV+ woman, matched on age and socioeconomic status. | HIV+: 29.9% had a c-section HIV−: 51.2% had a c-section | Yes | Acute hypertensive disorder of pregnancy (no further details) | 2.3 (44) | 4.6 (88) | 0.49 (0.05–4.51) | - | ||

| Frank et al., 2004 [48] | Retrospective Cohort | One tertiary hospital and five primary care clinics in Johannesburg, South Africa (2002) | Random sample of HIV+ and HIV− pregnant Soweto residents who delivered at a gestational age of 20 weeks or more in a public health facility. | No information provided | No | Pregnancy-induced hypertension which includes proteinuric hypertension, gestational hypertension, non proteinuric hypertension and chronic hypertension | 14.9 (704) | 14.8 (1,896) | 1.01 (0.79–1.28) | - | ||

| Pre-eclampsia defined as hypertension (diastolic blood pressure of ≥ 90 mm Hg on 2+ occasions, 4 hours apart) associated with proteinuria which developed after 20 weeks of pregnancy | 2.1 (704) | 3.0 (1,896) | 0.97 (0.59–1.62) | - | ||||||||

| Eclampsia (no further details) | 0.3 (704) | 0.3 (1,896) | 0.90 (0.18–4.46) | - | ||||||||

| Haeri et al., 2009 [21] | Retrospective Cohort | Two tertiary care centres in Columbia and North Carolina, USA (2000–2007) | All HIV+ women on ART and two HIV− controls for each HIV+ woman matched for age, race, parity, care location, delivery mode, insurance type and year of delivery. Excluded deliveries before 20 weeks gestation. | HIV+: 51.0% had a c-section HIV−: 52.0% had a c-section | Yes | Gestational hypertension (no further details) | 0.7 (151) | 4.3 (302) | 0.15 (0.02–1.14) | 0.18 (0.02–1.40) 2 | ||

| Pre-eclampsia defined according to the national working group for Hypertension in Pregnancy Guidelines | 6.0 (151) | 11.9 (302) | 0.50 (0.25–1.01) | 0.55 (0.26–1.18) 2 | ||||||||

| Kourtis et al., 2006 [22] | Retrospective Cohort | 20% of all community hospitals in the USA (1994 & 2003) | All HIV+ and HIV− pregnant women between 15-44 years of age who were hospitalised. | No information provided | Yes | Pre-eclampsia/hypertensive disorders of pregnancy defined according to ICD-9 codes | 7.7 (12,378) | 7.1 (8,784,767) | 1.09 (1.02–1.17) | - | ||

| Lionel et al. , 2008 [51] | Retrospective Cohort | One hospital in Vellore, India (2000–2002) | All HIV+ and HIV− women. | HIV+: 58.7% had a c-section HIV−: 21.5% had a c-section | Yes | Pregnancy-induced hypertension (no further details) | 21.1 (109) | 8.1 (23,277) | 3.02 (1.90–4.80) | - | ||

| Eclampsia (includes antepartum, intrapartum and postpartum) | 23.9 (109) | 0.8 (23,277) | 38.47 (24.21–61.14) | - | ||||||||

| Mattar et al ., 2004 [31] | Retrospective Cohort | One obstetric outpatient clinic in Sao Paulo, Brazil (2000–2002) | All women referred to the outpatient obstetric unit. Excluded women with pre-existing hypertension. | No information provided | Yes | Pre-eclampsia defined as hypertension (> = 140 mmHg x 90 mmHg) and proteinuria (> = 300 mg/24h) after 20 weeks of pregnancy | 0.8 (123) | 10.7 (1,708) | 0.07 (0.01–0.49) | - | ||

| Mmiro et al ., 1993 [39] | Prospective Cohort | One university hospital in Kampala, Uganda (1988–1990) | All HIV+ women and a random 10% sample of HIV− women. Only included women who lived within 15km of Mulago and agreed to deliver in the hospital. | No difference in the mode of delivery in HIV+ and HIV− women | No | Hypertension defined as diastolic blood pressure >90 mmHg | 3.7 (539) | 6.2 (660) | 0.58 (0.34–1.01) | - | ||

| Olagbuji et al ., 2010 [42] | Prospective Cohort | One tertiary hospital in Benin City, Nigeria (2007–2008) | HIV+ women who did not have AIDS, chronic medical disorders predating the pregnancy, multiple gestation or duration of ART intake of less than 8 weeks. A single HIV− control was selected for each HIV+ woman. | HIV+: 29.1% had a c-section HIV−: 20.2% had a c-section | Yes | Pregnancy-induced hypertension (no further details) | 4.9 (203) | 3.0 (203) | 1.70 (0.61–4.77) | - | ||

| Roman-Poueriet et al ., 2009 [29] | Retrospective Cohort | All main obstetric facilities, a social security hospital and two private clinics in La Romana, Dominican Republic (2003–2006) | All HIV+ and HIV− women. | HIV+: 42.5% had a c-section HIV−: 17.4% had a c-section | Yes | Pregnancy-induced hypertension (no further details) | 2.8 (252) | 0.5 (9,003) | 5.69 (2.54–12.74) | - | ||

| Singh et al., 2009 [52] | Prospective Cohort | One hospital in Imphal, India (2006–2008) | 50 HIV+ and 100 HIV− women who did not have medical or obstetric complications during pregnancy. | HIV+: 32.0% had a c-section HIV−: 10.0% had a c-section | Yes | Pre-eclamptic toxaemia (no further details) | 6.0 (50) | 8.0 (100) | 0.73 (0.19–2.90) | - | ||

| Suy et al., 2006 [13] | Prospective Cohort | One referral centre in Barcelona, Spain (2001–2003) | All HIV+ and HIV− women delivering after at least 22 weeks of pregnancy. | No information provided | Yes | Pre-eclampsia defined as the new onset of hypertension with 2 readings ≥6 hours apart of more than 140 mmHg systolic during gestation, delivery or immediate postpartum period, plus a dipstick reading of at least 1+ for proteinuria (0.1 g/l) confirmed by > 300 mg/24 h urine collection after 22 weeks of pregnancy | 11.0 (82) | 2.9 (8,768) | 4.18 (2.07–8.46) | - | ||

| Waweru et al. , 2009 [34] | Prospective Cohort | One maternity hospital in Kenya, Nairobi (Study dates not provided) | 57 HIV+ and HIV− women who were randomly selected. | Only follows up women in ante-partum period | Not clear | Pre-eclampsia (no further details provided) | 17.5 (57) | 12.3 (57) | 1.52 (0.53–4.32) | - | ||

| Wimalasundera et al. , 2002 [17] | Prospective Cohort | Two hospitals in London, UK (1990–2001) | 214 HIV+ women and a single HIV− control for each HIV+ woman matched for age, parity and ethnic origin. | Only follows up women in ante-partum period | Yes | Pre-eclampsia defined according to Higgins and de Swiet [74] | 4.2 (214) | 5.6 (214) | 0.74 (0.30–1.79) | - | ||

| Dystocia | ||||||||||||

| Chanrachakul et al., 2001 [53] | Retrospective Cohort | One tertiary hospital in Bangkok, Thailand (1991–1999) | All nulliparous HIV+ women delivering from 1991–1999 and all non-private, nulliparous HIV− women admitted in 1998. Excluded emergency c-section, deliveries before 37th week of gestation, multiple pregnancies or non cephalic presentation. | HIV+: 14.6% had a c-section HIV−: 15.0% had a c-section; analysis restricted to vaginal deliveries | No1 | Prolonged labour defined as labour longer than 12 hours | 29.2 (82) | 5.0 (1,540) | 7.86 (4.64–13.33) | - | ||

| Leroy et al ., 1998 [37] | Prospective Cohort | One tertiary hospital in Kigali, Rwanda (1992–1993) | All HIV+ women and one HIV− control for each HIV+ woman matched for age. Only included women resident in Kigali who attended antenatal clinic two days a week and wished to deliver in the hospital. | HIV+: 5.8% had a c-section HIV−: 6.0% had a c-section | No | Dystocia (no further details) | 7.7 (349) | 7.5 (349) | 1.04 (0.59–1.82) | - | ||

| Abnormal presentation (no further details) | 7.0 (356) | 5.6 (360) | 1.28 (0.70–2.36) | - | ||||||||

| Lionel et al. , 2008 [51] | Retrospective Cohort | One hospital in Vellore, India (2000–2002) | All HIV+ and HIV− women. | HIV+: 58.7% had a c-section HIV−: 21.5% had a c-section | Yes | Uterine Rupture (no further details) | 0.9 (109) | 0.3 (23,277) | 2.75 (0.38–19.98) | - | ||

| Minkoff et al., 1990 [24] | Prospective Cohort | Four prenatal clinics in New York, USA (1985–1989) | All HIV+ women who had a live, singleton birth; in three of the prenatal clinics all HIV− women were also recruited, and in one of the clinics two HIV− controls were selected for each HIV+ woman. | HIV+: 12.0% had a c-section HIV−: 18.0% had a c-section | No | Abnormal presentation (no further details) | 4.8 (84) | 5.9 (118) | 0.79 (0.22–2.80) | - | ||

| Wandabwa et al., 2008 [40] | Case-control | One hospital in Mulago, Uganada (2001–2002) | Case of ruptured uterus and controls were selected from women who had a gestation of 24 or more weeks, delivered a live, singleton baby by vaginal delivery, did not have episiotomy, tear of more than first degree or excessive blood loss. | All vaginal deliveries | No | Uterine rupture diagnosed both by clinical examination and at laparatomy | - | - | 2.40 (1.10–4.20) | 3.20 (1.50–7.20)3 | ||

| Intrauterine infections | ||||||||||||

| Aboud et al. 2009 [56] | Prospective Cohort (from an RCT) | Multiple hospitals and antenatal clinics in Malawi (Blantyre and Lilongwe), Tanzania (Dar es Salaam) and Zambia (Lusaka) (2001–2003) | All HIV+ women enrolled and one HIV− woman enrolled for every five HIV+ women. | No information provided | No | Puerperal sepsis (no further details) | 1.8 (1,558) | 0 (271) | 10.11 (0.62–166.11) | - | ||

| Chamiso, 1996 [36] | Prospective Cohort | One maternity hospital in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (1993–1995) | All HIV+ women and HIV− women matched to the HIV+ women for age and parity. | HIV+: 6.5% had a c-section HIV−: 9.2% had a c-section | No | Endometritis (no further details) | 9.8 (92) | 0 (173) | 39.48 (2.27–686.46) | - | ||

| Chanrachakul et al., 2001 [53] | Retrospective Cohort | One tertiary hospital in Bangkok, Thailand (1991–1999) | All nulliparous HIV+ women delivering from 1991–1999 and all non-private, nulliparous HIV− women admitted in 1998. Excluded emergency c-section, deliveries before 37th week of gestation, multiple pregnancies or non cephalic presentation. | HIV+: 14.6% had a c-section HIV−: 15.0% had a c-section | No1 | Puerperal infection (no further details) | 1.0 (96) | 1.0 (1,856) | 1.02 (0.13–7.68) | - | ||

| Figueroa-Damian, 1999 [28] | Prospective Cohort | Institute of Perinatology in Mexico City, Mexico(1989–1997) | 44 HIV+ women and two HIV− controls for each HIV+ woman, matched on age and socioeconomic status. | HIV+: 29.9% had a c-section HIV−: 51.2% had a c-section | Yes | Endometritis (no further details) | 0(44) | 4.6(88) | 0.21 (0.01–4.01) | - | ||

| Fiore et al., 2004 [55] | Prospective Cohort | 14 references centres in Italy, Spain, Sweden, Poland and Ukraine (1992–2003) | HIV+ women were matched the first HIV− woman delivering after the infected index case on age ethnicity, parity and whether admitted to the delivery unit in active labour. | All vaginal deliveries | Yes | Endometritis (no further details) | 4.4 (250) | 2.0 (250) | 2.26 (0.77–6.59) | - | ||

| Kourtis et al., 2006 [22] | Retrospective Cohort | 20% of all community hospitals in the USA (1994 & 2003) | All HIV+ and HIV− pregnant women between 15–44 years of age who were hospitalised. | No information provided | Yes | Major puerperal sepsis identified using ICD-9 codes | 2.9 (12,378) | 0.9 (8,784,767) | 3.37 (3.03–3.74)767)n sepsis (no further details)ere sleHIV+ woman there were two HIV− | - | ||

| Lepage et al. 1991 [38] | Prospective Cohort | One hospital in Kigali, Rwanda (1988–1989) | All HIV+ women and an equal number of HIV− women matched for age and parity. Women had to have lived for at least six months in a district within a diameter of <10 Km from the hospital and delivered a live newborn. | No information provided | No | Endometritis (no further details) | 0.9 (215) | 0.9 (216) | 1.00 (0.14–7.20) | - | ||

| Minkoff et al., 1990 [24] | Prospective Cohort | Four prenatal clinics in New York, USA (1985–1989) | All HIV+ women who had a live, singleton birth; in three of the prenatal clinics all HIV− women were also recruited, and in one of the clinics two HIV− controls were selected for each HIV+ woman. | HIV+: 12.0% had a c-section HIV−: 18.0% had a c-section | No | Endometritis (no further details) | 4.4 (91) | 2.4 (126) | 1.89 (0.41–8.64) | - | ||

| Okong et al. 2004 [41] | Case-control | One hospital in Kampala, Uganda (1996–1997) | For each case of postpartum endometritis and myometritis (PPEM), two controls without PPEM were randomly recruited, matched for mode of delivery. | Cases and controls were matched for mode of delivery | No | Endometritis defined as auxiliary temperature ≥38oC on 2 different occasions 24 hours apart, with a tender uterus and foul-smelling or purulent vaginal discharge between delivery and 42 days postpartum | - | - | 2.74 (1.34–5.65) | - | ||

| Onah et al. , 2007 [43] | Retrospective Cohort | One university hospital in Enugu, Nigeria (2002–2004) | All HIV+ women and for every HIV+ woman the next two HIV− women who delivered were selected as controls. | HIV+: 8.1% had a c-section HIV−: 11.0% had a c-section | Yes | Puerperal sepsis (no further details) | 8.1 (62) | 0 (100) | 19.23 (1.04–354.04) | - | ||

| Peret et al ., 1993 [30] | Prospective Cohort | One maternity hospital in Belo Horizonte, Brazil (2001–2003) | 82 HIV+ women and 123 HIV− women matched for mode of delivery, gestational age at delivery and maternal age. Only included women if they did not have chronic diseases and/or complications of pregnancy. | HIV+: 72.0% had a c-section HIV−: 72.0% had a c-section | Yes | Endometritis defined as febrile morbidity with a tender uterus and/or foul-smelling vaginal discharge | 4.9 (82) | 0 (123) | 14.16 (0.75–266.61) | - | ||

| Temmerman et al., 1994 [35] | Prospective Cohort | One health centre in Nairobi, Kenya (1989–1991) | All HIV+ women and a sample of HIV− women matched for age and parity to each HIV+ woman. | HIV+: 1.9% had a c-section HIV−: 3.8% had a c-section | No | Postpartum endometritis diagnosed if at ≥two of the following symptoms were present: fever of >38oC, foul lochia and uterine tenderness | 10.3 (253) | 4.2 (265) | 2.64 (1.28–5.47) | - | ||

Information was not supplied in the published paper so whether antiretroviral treatment should have been available was based on the study dates and study location; for two studies it was not clear from the study dates and location whether ART would be available so the information was inferred from the literature.

a) Bangkok, Thailand between 2001: No ART treatment based on the UNAIDS data accessed on 29th October 2012 at http://www.unaids.org/en/dataanalysis/datatools/aidsinfo/.

b) Bloemfontein, South Africa in 2001: No ART treatment based on the UNAIDS data accessed on 29th October 2012 at http://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/southafrica/.

Adjusted for smoking and cocaine use.

Adjusted for age, type of house, the distance from home to Mulago hospital, permission to attend health unit, person paying for hospital upkeep, previous length of labour and previous delivery by c-section.

Table 2. Summary of studies of HIV and obstetric complications which only looked at births by caesarean section.

| Reference | Study design | Study Setting | Study Population | ART Available | Definition of obstetric complication | % of HIV positive with obstetric complication (total number of HIV+ women) | % of HIV negative with obstetric complication (total number of HIV+ women) | Crude Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

| Haemorrhage | |||||||||

| Chama and Morrupa, 2008 [44] | Prospective Cohort | One university hospital in Maiduguri, Nigeria (2006) | All HIV+ women and an equivalent number of HIV− women who delivered by elective c-section. | Yes | Intra-operative haemorrhage defined as any bleeding during surgery requiring blood transfusion or a fall in packed cell volume ≥4% | 23.1 (52) | 40.4 (52) | 0.44 (0.19–1.04) | - |

| Hypertensive diseases of pregnancy | |||||||||

| Chama and Morrupa, 2008 [44] | Prospective Cohort | One university hospital in Maiduguri, Nigeria (2006) | All HIV+ women and an equivalent number of HIV− women who delivered by elective c-section. | Yes | Postpartum pregnancy-induced hypertension (no further details) | 0 (52) | 1.9 (52) | 0.33 (0.01–8.21) | - |

| Sepsis | |||||||||

| Cavasin et al., 2009 [25] | Retrospective Cohort | Two health centres (one of which is part of a university hospital) in New Orleans in the USA (1998–2004) | All HIV+ women undergoing c-section; HIV− women were those who delivered by c-section during the same time period. | Yes | Post-operative endometritis defined as temperature elevation above 38°C with uterine tenderness and requiring antibiotics treatment in the absence of other aetiology for fever | 12.6 (119) | 12.1 (264) | 1.05 (0.54–2.01) | - |

| Chama and Morrupa, 2008 [44] | Prospective Cohort | One university hospital in Maiduguri, Nigeria (2006) | All HIV+ women and an equivalent number of HIV− women who delivered by elective c-section. | Yes | Wound sepsis (not clearly defined) | 3.8 (52) | 5.8 (52) | 0.65 (0.10–4.08) | - |

| Fiore et al., 2004 [55] | Prospective Cohort | 14 references centres in Italy, Spain, Sweden, Poland and Ukraine (1992–2003) | All HIV+ women delivering by elective c-section were matched with the first HIV− woman delivering by elective c-section after the infected index case for age, ethnicity, parity, and whether admitted to the delivery unit in active labour. | Yes | Wound infection (no further details) | 0.6 (158) | 0 (158) | 3.02 (0.12–74.67) | - |

| Endometritis (no further details) | 1.3 (158) | 2.5 (158) | 0.49 (0.09–2.73) | - | |||||

| Grubert et al ., 1999 [18] | Retrospective Cohort | One medical facility in Germany (1987–1999) | All HIV+ women delivering by c-section were matched to an HIV− woman on age, duration of gestation and indication for caesarean. | Yes | Endometritis (no further details) | 4.8 (62) | 0 (62) | 7.35 (0.37–145.40) | - |

| Louis et al., 2007 [26] | Prospective Cohort | 19 different academic medical centres in the USA (1999–2002) | All women of known HIV status having a c-section at a gestational age of >20 weeks and who delivered a singleton infant of at least 500g birth weight. | Yes | Maternal sepsis defined as the presence of positive blood cultures and cardiovascular decompensation | 1.1 (378) | 0.2 (54,281) | 6.98 (2.55–19.15) | 6.2 (2.3–17.0)2 |

| Wound infection defined as erythema of the incision accompanied by purulent drainage requiring wound care | 2.1 (378) | 1.3 (54,281) | 1.67 (0.83–3.39) | 1.6 (0.8–3.3)2 | |||||

| Endometritis defined as persistently elevated postpartum body temperature with uterine tenderness in the absence of a non-uterine source | 11.6 (378) | 5.8 (54,281) | 2.14 (1.56–2.93) | 1.9 (1.3–2.6) 2 | |||||

| Maiques et al., 2010 [14] | Retrospective cohort | One referral hospital in Valencia, Spain (1997–2007) | All HIV+ women on ART and having a c-section; for every HIV+ woman the HIV− women who delivered by c-section before and after were selected as controls. | Yes | Wound infection or hematoma (no further details) | 5.0 (160) | 2.8 (320) | 1.82 (0.69–4.81) | - |

| Endometritis defined using clinical signs and a positive vaginal swab | 0.6 (160) | 0.6 (320) | 1.00 (0.09–11.11) | - | |||||

| Maiques-Montesinos et al. , 1999 [15] | Retrospective Cohort | One maternity hospital in Valencia, Spain (1987–1996) | All HIV+ women delivering by c-section were matched to HIV− women for indication for c-section, stage of labour, number of foetuses and date of delivery. | No | Sepsis (no further details) | 4.4 (45) | 0 (90) | 10.40 (0.49–221.37) | - |

| Wound infection or hematoma (no further details) | 26.7 (45) | 6.7 (90) | 5.09 (1.76–14.69) | - | |||||

| Endometritis (no further details) | 2.2 (45) | 4.4 (90) | 0.49 (0.05–4.50) | - | |||||

| Moodlier et al. , 2007 [49] | Retrospective Cohort | One tertiary hospital in Durban, South Africa (2003–2004) | All women undergoing a c-section with known HIV status. | No1 | Wound sepsis defined as the breakdown of the suture line as a result of a subcutaneous infectious process | 5.4 (186) | 8.0 (175) | 0.65 (0.28–1.51) | - |

| Endometritis defined as a sustained pyrexia (auxiliary temp greater than 38°C) post-delivery (excluding the first 24 hours) | 5.9 (186) | 1.1 (175) | 5.44 (1.19–24.89) | - | |||||

| Panburana et al., 2003 [54] | Prospective Cohort | One tertiary hospital in Bangkok, Thailand (1999–2001) | Do not provide specific details on how HIV+ and HIV− women were selected but did exclude women who had a preterm delivery. | Yes | Endometritis (no further details) | 2.7 (74) | 1.7 (360) | 1.64 (0.32–8.28) | - |

| Rodriguez et al., 2001 [27] | Prospective Cohort | One facility in the USA (no further details provided) (1992–2000) | All HIV+ women delivering by c-section were matched to an HIV− woman on age, race, year of delivery and indication for c-section. | Yes | Sepsis (no further details) | 1.2 (86) | 0 (86) | 3.04 (0.12–75.55) | - |

| Wound infection defined as purulent drainage, induration or tenderness | 7.0 (86) | 4.7 (86) | 1.54 (0.42–5.65) | - | |||||

| Postpartum endometritis defined as a temperature >38oC on two consecutive readings at an 8 hour interval, exclusive of the first 24 hours after delivery, with uterine tenderness, foul lochia, and no other apparent causes for fever | 16.3 (86) | 10.5 (86) | 1.66 (0.68–4.08) | - | |||||

| Semprini et al., 1995 [20] | Retrospective Cohort | Seven centres in Italy (1989–1993) | All HIV+ women delivering by c-section were matched to an HIV− woman on indication for c-section, active labour and whether they had ruptured membranes. | No | Sepsis (no further details) | 0.6 (156) | 0 (156) | 3.02 (0.12–74.69) | - |

| Wound infection (no further details) | 8.3 (156) | 1.9 (156) | 4.64 (1.29–16.61) | - | |||||

| Febrile endometritis (no further details) | 13.5 (156) | 2.6 (156) | 5.91 (1.98–17.65) | - | |||||

| Urbani et al., 2001 [50] | Prospective Cohort | Two teaching hospitals in South Africa (1998) | 307 women were enrolled irrespective of HIV status, and subsequently HIV status was ascertained. Women were excluded if they had diabetes mellitus. | No | Wound infection (no further details) | 6.8 (59) | 3.2 (248) | 2.18 (0.63–7.51) | - |

| Endometritis defined as fever of ≥38oC on 2 occasions at least 4 hours apart and more than 24 hours post-operatively, tachycardia of >100 beats per minute on 2 occasions at least 4 hours apart and more than 24 hours post-operatively, and tenderness of the cervix on movement | 23.7 (59) | 6.9 (248) | 4.23 (1.95–9.19) | - | |||||

| Zvandasara et al. , 2007 [45] | Prospective Cohort | One maternity hospital in Harare, Zimbabwe (2006) | All patients undergoing a c-section with known HIV status. | No | Wound infection was diagnosed in the presence of purulent discharge from the incision with induration and tenderness with or without fever | 23.8 (164) | 15.7 (382) | 1.67 (1.06–2.63) | - |

| Postpartum endometritis defined as temperature ≥38oC on 2 successive readings at an 8 hour interval (excluding the 24 hours after delivery) and uterine tenderness, slight vaginal bleeding or foul smelling odour and no other apparent causes of fever | 25.6 (164) | 20.9 (382) | 1.30 (0.85–1.99) | - | |||||

Information was not supplied in the published paper so whether antiretroviral treatment should have been available was based on the study dates and study location; for one study it was not clear from the study dates and location whether ART would be available so the information was inferred from the literature.

a) Durban, South Africa in 2004: No ART treatment based on the UNAIDS data accessed on 20th December 2012 at http://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/southafrica/.

Adjusted for number of previous caesarean section.

Risk of Bias Within and Between Data Sets

The assessment of the risk of bias is summarised in Tables 3 and 4. Only 23 of the 66 data sets provided a definition for the obstetric complication: from eight of the 19 data sets (42%) reporting on hypertensive disorders to seven amongst the 25 data sets (28%) for intrauterine infections. The risk of bias in the ascertainment of obstetric complications cases was judged to be high for 29 of the 66 data sets; most of which relied on medical records to ascertain the nature of the complication.

Table 3. Risk of bias within studies which include vaginal deliveries.

| Reference | Definition of obstetric complication | Ascertainment of obstetric complication | Completeness of data | Adjustment for confounders | Selection of comparison group | |||||

| HAEMORRHAGE | ||||||||||

| Aboud et al. 2009 [56] with supplementary information from [75] | No definitions provided for antepartum haemorrhage or postpartum haemorrhage | The pregnancy was followed prospectively, although it was not clear who collected the outcome data | 6.9% of HIV+ women were lost to follow up compared with 7.6% of HIV− women | None | Unclear on exact selection methods; however no HIV− women were selected from one of the study sites | |||||

| High risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | High risk | High risk | ||||||

| Azria et al. , 2010 [16] | Definition provided for postpartum haemorrhage | Hospital record review | Eight medical records of HIV+ women were missing data; no information for HIV− women | HIV+ and HIV− women were matched on key confounders | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| Low risk | High risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Braddick et al., 1990 [32] | Definition provided for antepartum haemorrhage | Hospital record review | 0.6% of women refused to participate | None | HIV− Women were selected based on close proximity to the follow up clinic, but this selection criteria was not applied to HIV+ women | |||||

| Low risk | High risk | Low risk | High risk | High risk | ||||||

| Chamiso, 1996 [36] | No definitions provided for placenta praevia, postpartum haemorrhage or retained placenta | Recorded by a general practitioner blinded to woman's HIV status | 22% of HIV+ women were lost to follow up | HIV+ and HIV− women were matched on key confounders | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| High risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Chanrachakul et al., 2001 [53] | No definitions provided for postpartum haemorrhage or retained placenta | Hospital record review | No information provided | None | HIV+ and HIV− women were enrolled from the same hospital; however HIV+ women were managed using traditional labour management and HIV− women were managed using active labour management | |||||

| High risk | High risk | Unclear risk | High risk | High risk | ||||||

| De Groot et al., 2003 [46] | Definitions provided for antepartum haemorrhage and postpartum haemorrhage | Hospital record review | 2% of medical files selected into study were missing HIV status | None | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| Low risk | High risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Figueroa-Damian, 1999 [28] | No definition provided for postpartum haemorrhage | The pregnancy was followed prospectively, although it was not clear who collected the outcome data | No information provided | HIV+ and HIV− women were matched on key confounders | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| High risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Haeri et al., 2009 [21] | No definition provided for placental abruption | Hospital record review | No information provided | HIV+ and HIV− women were matched on key confounders | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same two tertiary care centres | |||||

| High risk | High risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Kourtis et al., 2006 [22] | ICD-9 codes were used to define antepartum haemorrhage | Hospital discharge data | No information provided | None1 | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospitals | |||||

| Low risk | High risk | Unclear risk | High risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Leroy et al ., 1998 [37] | No definitions provided for postpartum haemorrhage or retained placenta | Recorded by a midwife blinded to woman's HIV status | 5.2% refusal rate; 4.7% lost to follow up | HIV+ and HIV− women were matched on key confounders | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Lionel et al ., 2008 [51] | Placental abruption defined as grade III but no definitions for placenta praevia and PPH | Hospital record review | No information provided | None | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| Unclear risk | High risk | Unclear risk | High risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Louis et al., 2006 [23] | No definition provided for postpartum haemorrhage | Hospital record review | No information provided | None | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| High risk | High risk | Unclear risk | High risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Minkoff et al., 1990 [24] | No definitions provided for placenta praevia, placental abruption, peripartum haemorrhage or retained placenta | Method of ascertaining outcome not clear | 10% of HIV+ women refused to participate | None | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same clinics | |||||

| High risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Mmiro et al ., 1993 [39] | No definitions provided for antepartum haemorrhage or postpartum haemorrhage | Hospital record review | No information provided | None | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| High risk | High risk | Unclear risk | High risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Peret et al ., 1993 [30] | Definition provided for postpartum haemorrhage | The pregnancy was followed prospectively, although it was not clear who collected the outcome data | No information provided | HIV+ and HIV− women were matched on key confounders | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Van Eijk et al. , 2007 [33] | No definition provided for peripartum haemorrhage | Method of ascertaining outcome not clear | 1.5% of women had missing data and were excluded | None | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| High risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | ||||||

| HYPERTENSIVE DISEASES OF PREGNANCY | ||||||||||

| Aboud et al. 2009 [56] with supplementary information from [75] | No definition provided for hypertension | The pregnancy was followed prospectively, although it was not clear who collected the outcome data | 6.9% of HIV+ women were lost to follow up compared with 7.6% of HIV− women | None | Unclear on exact selection methods; however no HIV− women were selected from one of the study sites | |||||

| High risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | High risk | High risk | ||||||

| Bodkin et al., 2005 [47] | No definitions provided for pregnancy-induced hypertension or eclampsia | Hospital record review | 49.6% of women refused to be tested for HIV | HIV+ and HIV− women were only matched on whether their pregnancy was high-risk, medium-risk or low-risk | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| High risk | High risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Boer et al., 2006 [19] | Definition provided for pre-eclampsia | Method of ascertaining outcome not clear | No information provided | HIV+ and HIV− women were matched on key confounders | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same medical centres | |||||

| Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Chamiso, 1996 [36] | Definition provided from pregnancy-induced hypertension | Recorded by a general practitioner blinded to woman's HIV status | 22% of HIV+ women were lost to follow up | HIV+ and HIV− women were matched on key confounders | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | ||||||

| De Groot et al. , 2003 [46] | Definitions provided for pre-eclampsia and eclampsia | Hospital record review | 2% of medical files selected into study were missing HIV status | None | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| Low risk | High risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Figueroa-Damian, 1999 [28] | No definition provided for acute hypertensive disorder of pregnancy | The pregnancy was followed prospectively, although it was not clear who collected the outcome data | No information provided | HIV+ and HIV− women were matched on key confounders | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| High risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Frank et al., 2004 [48] | Definitions provided for pregnancy-induced hypertension and pre-eclampsia but not for eclampsia | Hospital record review | 27% of files reviewed did not have known HIV status | None | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital and clinics | |||||

| Unclear risk | High risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Haeri et al., 2009 [21] | Definition provided for pre-eclampsia but not for gestational hypertension | Hospital record review | No information provided | HIV+ and HIV− women were matched on key confounders and adjusted analysis conducted | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same two tertiary care centres | |||||

| Unclear risk | High risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Kourtis et al., 2006 [22] | ICD-9 codes were used to define pre-eclampsia/ hypertensive disorders of pregnancy | Hospital discharge data | No information provided | None1 | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospitals | |||||

| Low risk | High risk | Unclear risk | High risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Lionel et al. , 2008 [51] | No definitions provided for pre-eclampsia and eclampsia | Hospital record review | No information provided | None | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| High risk | High risk | Unclear risk | High risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Mattar et al ., 2004 [31] | Definition provided for pre-eclampsia | Hospital record review | No information provided | None | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same clinic | |||||

| Low risk | High risk | Unclear risk | High risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Mmiro et al ., 1993 [39] | Definition provided for hypertension | Hospital record review | No information provided | None | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| Low risk | High risk | Unclear risk | High risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Olagbuji et al ., 2010 [42] | No definition provided for pregnancy-induced hypertension | Method of ascertaining outcome not clear | No information provided | State that HIV− women were matched to HIV+ women but do not state what the matching characteristics were | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| High risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Roman-Poueriet et al ., 2009 [29] | No definition provided for pregnancy-induced hypertension | Hospital record review | No information provided | None | Women were recruited from a range of public, private clinics and hospitals and a specialist HIV clinic | |||||

| High risk | High risk | Unclear risk | High risk | Unclear risk | ||||||

| Singh et al., 2009 [52] | No definition provided for pre-eclamptic toxaemia | States that the “antenatal complications in both study groups were observed” | No information provided | None | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| High risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | High risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Suy et al., 2006 [13] | Definition provided for pre-eclampsia | Using a database | No information provided | Adjusted analysis was conducted but it is not clear what factors were adjusted for, therefore only the crude estimate was extracted | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| Low risk | High risk | Unclear risk | High risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Waweru et al. , 2009 [34] | No definition provided for pre-eclampsia | Method of ascertaining outcome not clear | No information provided | None | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| High risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | High risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Wimalasundera et al. , 2002 [17] | Definition provided for pre-eclampsia | Method of ascertaining outcome not clear | No information provided | HIV+ and HIV− women were matched on key confounders | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospitals | |||||

| Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | ||||||

| DYSTOCIA | ||||||||||

| Chanrachakul et al., 2001 [53] | Definition provided for prolonged labour | Hospital record review | No information provided | None | Although HIV+ and HIV− women were enrolled from the same hospital, HIV+ women were managed using traditional labour management and HIV− women were managed using active labour management | |||||

| Low risk | High risk | Unclear risk | High risk | High risk | ||||||

| Leroy et al ., 1998 [37] | No definitions provided for dystocia or abnormal presentation | Recorded by a midwife blinded to woman's HIV status | 5.2% refusal rate; 4.7% lost to follow up | HIV+ and HIV− women were matched on key confounders | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Lionel et al. , 2008 [51] | No definition provided for uterine rupture | Hospital record review | No information provided | None | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| High risk | High risk | Unclear risk | High risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Minkoff et al., 1990 [24] | No definition provided for abnormal presentation | Method of ascertaining outcome not clear | 10% of HIV+ women refused to participate | None | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same clinics | |||||

| High risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Wandabwa et al., 2008 [40] | Definition provided for uterine rupture | Cases of ruptured uterus were identified by clinical examination and at laparatomy | No information provided | Adjusted analysis conducted | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| Low risk | Low risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | ||||||

| INTRAUTERINE INFECTION | ||||||||||

| Aboud et al. 2009 [56] with supplementary information from [75] | No definition provided for puerperal sepsis | The pregnancy was followed prospectively, although it was not clear who collected the outcome data | 6.9% of HIV+ women were lost to follow up compared with 7.6% of HIV− women | None | Unclear on exact selection methods; however no HIV− women were selected from one of the study sites | |||||

| High risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | High risk | High risk | ||||||

| Chamiso, 1996 [36] | No definition provided for endometritis | Recorded by a general practitioner blinded to woman's HIV status | 22% of HIV+ women were lost to follow up | HIV+ and HIV− women were matched on key confounders | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| High risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Chanrachakul et al., 2001 [53] | No definition provided for puerperal infection | Hospital record review | No information provided | None | Although HIV+ and HIV− women were enrolled from the same hospital, HIV+ women were managed using traditional labour management and HIV− women were managed using active labour management | |||||

| High risk | High risk | Unclear risk | High risk | High risk | ||||||

| Figueroa-Damian, 1999 [28] | No definition provided for endometritis | The pregnancy was followed prospectively, although it was not clear how the outcome data was collected | No information provided | HIV+ and HIV− women were matched on key confounders | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| High risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Fiore et al., 2004 [55] | No definition provided for endometritis | Women were evaluated for the development of obstetric complications | No information provided | HIV+ and HIV− women were matched on key confounders | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same delivering centres | |||||

| High risk | Low risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Kourtis et al., 2006 [22] | ICD-9 codes used to define major puerperal sepsis | Hospital discharge data | No information provided | None1 | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospitals | |||||

| Low risk | High risk | Unclear risk | High risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Lepage et al. 1991 [38] | No definition provided for endometritis | Hospital record review | 21% refusal rate; 16% of HIV− women and 21% of HIV+ women were lost to follow up | HIV+ and HIV− women were matched on key confounders | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| High risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Minkoff et al., 1990 [24] | No definition provided for endometritis | Method of ascertaining outcome not clear | 10% of HIV+ women refused to participate | None | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same clinics | |||||

| High risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Okong et al. 2004 [41] | Definition provided for endometritis | Cases of endometritis were identified by midwives | 8% of cases and controls refused to participate | None | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Onah et al. , 2007 [43] | No definition provided for puerperal sepsis | Hospital record review | 19% of HIV− women had to be excluded because their medical records could not be located | None | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| High risk | High risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Peret et al ., 1993 [30] | Definition provided for endometritis | The pregnancy was followed prospectively, although it was not clear who collected the outcome data | No information provided | HIV+ and HIV− women were matched on key confounders | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Temmerman et al., 1994 [35] | Definition provided for endometritis | Identified by a research nurse | 2.3% women refused to participate; missing data for 38% of HIV+ and 35% of HIV− women on endometritis | HIV+ and HIV− women were matched on key confounders | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same health centre | |||||

| Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | ||||||

Adjusted odds ratios stratified by two time periods were available but were not extracted.

Table 4. Risk of bias within caesarean section studies.

| Reference | Definition of obstetric complication | Ascertainment of obstetric complication | Completeness of data | Adjustment for confounders | Selection of comparison group | |||||

| HAEMORRHAGE | ||||||||||

| Chama and Morrupa, 2008 [44] | Definition provided for intra-operative haemorrhage | No information provided | No information provided | None | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | High risk | Low risk | ||||||

| HYPERTENSIVE DISEASES OF PREGNANCY | ||||||||||

| Chama and Morrupa, 2008 [44] | No definition provided for pregnancy-induced hypertension | No information provided | No information provided | None | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| High risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | High risk | Low risk | ||||||

| INTRAUTERINE INFECTION | ||||||||||

| Cavasin et al., 2009 [25] | Definition provided for endometritis, but not for septic pelvic thrombosis | Hospital record review | No information provided | None | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same two health centres | |||||

| Unclear risk | High risk | Unclear risk | High risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Chama and Morrupa, 2008 [44] | No definition provided for wound sepsis | No information provided | No information provided | None | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| High risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | High risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Fiore et al., 2004 [55] | No definitions provided for wound infection or endometritis | Women were evaluated for the development of obstetric complications | No information provided | HIV+ and HIV− women were matched on key confounders | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same delivering centres | |||||

| High risk | Low risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Grubert et al ., 1999 [18] | No definition provided for endometritis | Method of ascertaining outcome not clear | No information provided | HIV+ and HIV− women were matched on key confounders | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same medical facility | |||||

| High risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Louis et al., 2007 [26] | Definitions provided maternal sepsis, wound infection and endometritis | Method of ascertaining outcome not clear | No information provided | Adjusted analysis conducted | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same medical centres | |||||

| Low risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Maiques et al., 2010 [14] | Definition provided for endometritis, but not for wound infection | Method of ascertaining outcome not clear | No information provided | None | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | High risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Maiques-Montesinos et al. , 1999 [15] | No definitions provided for sepsis, wound infection/haematoma or endometritis | Hospital record review | No information provided | HIV+ and HIV− women were matched on key confounders | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| High risk | High risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Moodlier et al. , 2007 [49] | Definitions provided wound sepsis and endometritis | Hospital record review | Only 1% of charts were missing, but state that about half of the women refused HIV testing | None | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| Low risk | High risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Panburana et al., 2003 [54] | No definition provided for endometritis | Simply states that all complications were “recorded in both study and control groups” | No information provided | None | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| High risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | High risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Rodriguez et al., 2001 [27] | Definition provided for endometritis and wound infection, but not for sepsis | Hospital record review | 11% of HIV+ women did not have records available for review | HIV+ and HIV− women were matched on key confounders | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| Unclear risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Semprini et al., 1995 [20] | No definitions provided for sepsis, wound infection or febrile endometritis | Method of ascertaining outcome not clear | No information provided | HIV+ and HIV− women were matched on key confounders | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same centres | |||||

| High risk | Unclear risk | Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Urbani et al., 2001 [50] | Definition provided for endometritis but not for wound infection | Identified by a researcher | 95% of women undergoing c-section were recruited | None | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospitals | |||||

| Unclear risk | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | ||||||

| Zvandasara et al. , 2007 [45] | Definition provided for wound sepsis | Identified by a researcher | No patients were excluded | None | HIV+ and HIV− women selected from the same hospital | |||||

| Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | ||||||

Very few studies had sufficient information on the completeness of the data to enable the risk of bias to be assessed and only 17 of 66 data sets were classified as at low risk of bias. In particular, studies relying on medical records tended not to report how many records had to be excluded due to missing information (e.g. HIV status).

Overall, 25 of 66 data sets either adjusted for confounders in their analysis or matched the HIV-infected and uninfected women with respect to some key confounders. The majority of the data sets (58 of 66) were judged to be at low risk of bias in the selection of the comparison group of HIV-uninfected women.

There was no evidence of publication bias for any of the outcomes included in the analysis with the exception of pre-eclampsia (p = 0.01) (Supplementary material, Figure S1).

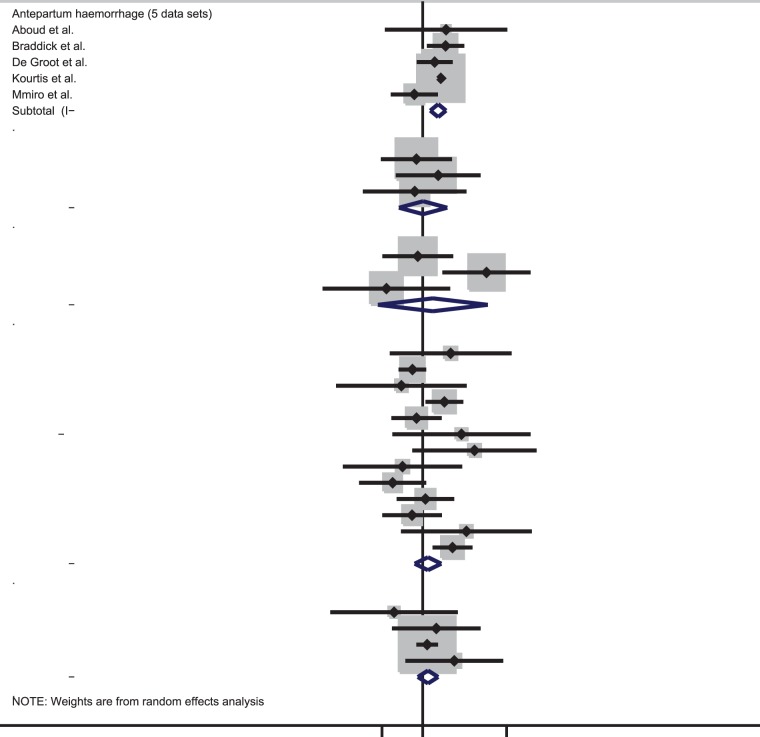

Effect of HIV on obstetric haemorrhage

The prevalence of antepartum haemorrhage was higher in HIV-infected than uninfected women in four out of five data sets (Table 1). Meta-analysis indicated that HIV-infected women have double the odds of antepartum haemorrhage [summary odds ratio (OR): 2.06, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.42–2.97] (Figure 2). There was no evidence for between-study heterogeneity (I2: 27.5%, p-value = 0.24). Based on three data sets, there was no evidence for an association between HIV and either placenta praevia (summary OR: 1.02, 95% CI: 0.33–3.14, I2: 0%, p-value = 0.70) or placental abruption (summary OR: 1.61, 95% CI: 0.12–20.79, I2: 76.1%, p-value = 0.02) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Forest plot showing the strength of association between HIV and obstetric haemorrhage in studies with vaginal deliveries only or included both vaginal deliveries and c-section deliveries.

Thirteen data sets compared the prevalence of postpartum haemorrhage in HIV-infected and uninfected women with ORs ranging from 0.25 to 11.18. The meta-analysis suggests there is no evidence that HIV increases the odds of postpartum haemorrhage (summary OR: 1.28, 95% CI: 0.69–2.38, I2: 53.4%, p = 0.01). Similarly, there was no evidence for increased odds of retained placenta with HIV infection (summary OR: 1.28, 95% CI: 0.80–2.06, I2: 0%, p = 0.50).

One study looked at the association between HIV and postpartum haemorrhage amongst women undergoing a caesarean section (Table 2). There was no evidence of an association between HIV and postpartum haemorrhage (OR: 0.44, 95%CI: 0.19–1.04).

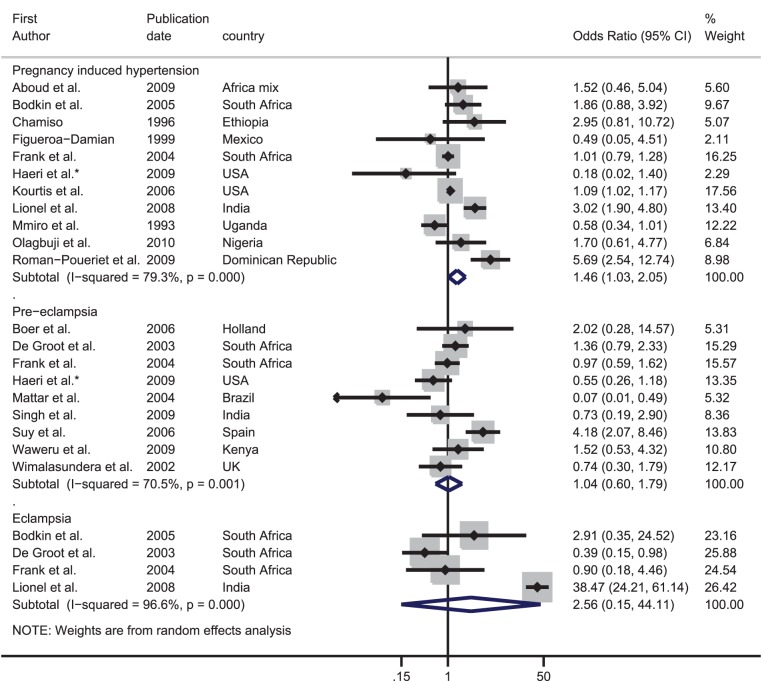

Effect of HIV on hypertensive disorders of pregnancy

Out of the 11 data sets with data on pregnancy-induced hypertension, eight found that HIV-infected women were at increased risk of pregnancy-induced hypertension (Table 1). The meta-analysis showed some evidence for increased odds of pregnancy-induced hypertension with HIV infection (summary OR: 1.46, 95% CI: 1.03–2.05). However, there was strong evidence for between-study heterogeneity (I2: 79.3%, p-value<0.001) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Forest plot showing the strength of association between HIV and hypertensive diseases of pregnancy.

*Adjusted odds ratio.

Nine data sets examined the association between HIV and pre-eclampsia; four of these found a higher prevalence in HIV-infected women than uninfected women. There was no evidence that HIV infection was associated with pre-eclampsia (summary OR: 1.04, 95% CI: 0.60–1.79, I2: 70.5%, p-value = 0.001).

The ORs from the four data sets comparing the prevalence of eclampsia in HIV-infected and uninfected women varied from 0.39 to 38.47. The meta-analysis produced a summary OR of 2.56, however the confidence intervals were very wide (95% CI: 0.15–44.11) and there was strong evidence for between-study heterogeneity (I2: 96.6%, p-value<0.001).

There was one data set from Nigeria which was restricted to caesarean sections. There was no evidence of an association between HIV and postpartum pregnancy-induced hypertension (OR: 0.33, 95%CI 0.01–8.21).

Effect of HIV on dystocia

There were only six data sets where the outcome could be broadly categorised as dystocia (Table 1, Figure 4). One data set from Rwanda found no association between HIV and dystocia (OR: 1.04, 95% CI 0.59–1.82), whilst a study from Thailand indicated that HIV-infected women have nearly eight times the odds of prolonged labour compared with uninfected women (OR: 7.86, 95% CI: 4.64–13.33). Two data sets reported on abnormal presentation, and there was no evidence for an association between HIV and abnormal presentation in the meta-analysis (summary OR: 1.17, 95% CI: 0.68–2.03, I2: 0%, p = 0.50). Conversely, both data sets which compared the prevalence of uterine rupture showed an increased risk in HIV-infected women, giving a summary OR of 3.14 (95% CI: 1.51–6.50, I2:0%, p = 0.89).

Figure 4. Forest plot showing the strength of association between HIV and dystocia.

*Adjusted odds ratio.

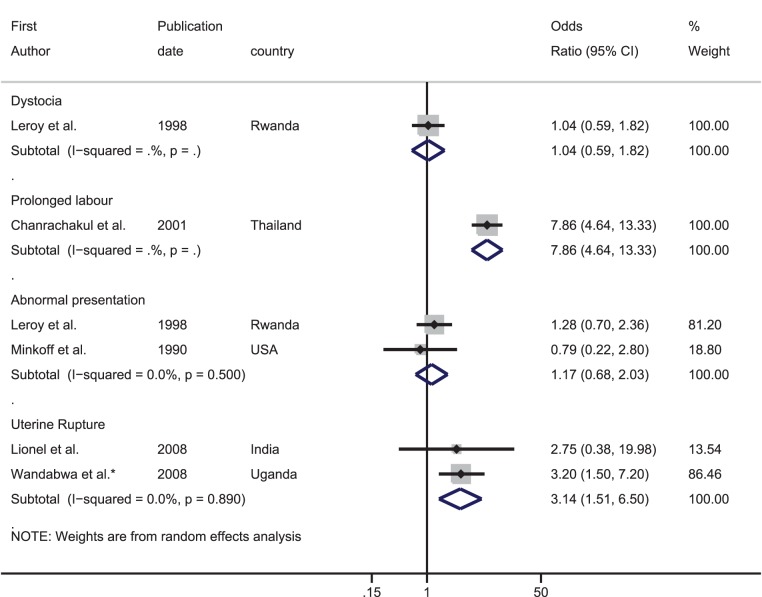

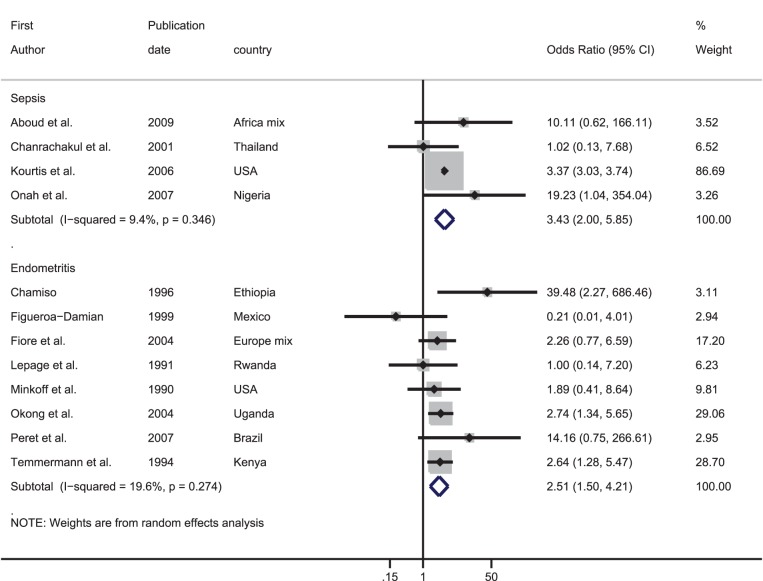

Effect of HIV on intrauterine infections

Figure 5 shows the association between HIV and intrauterine infections. Meta-analysis based on four data sets indicated that HIV-infected women have over three times the odds of having puerperal sepsis compared with uninfected women (summary OR 3.43, 95% CI: 2.00–5.85, I2: 9.4%, p-value = 0.35). There was also evidence from eight data sets that HIV-infected women had over 2.5 times the risk of endometritis compared with uninfected women (summary OR 2.51, 95% CI: 1.50–4.21, I2: 19.6%, p-value = 0.27).

Figure 5. Forest plot showing the strength of association between HIV and intrauterine infection.

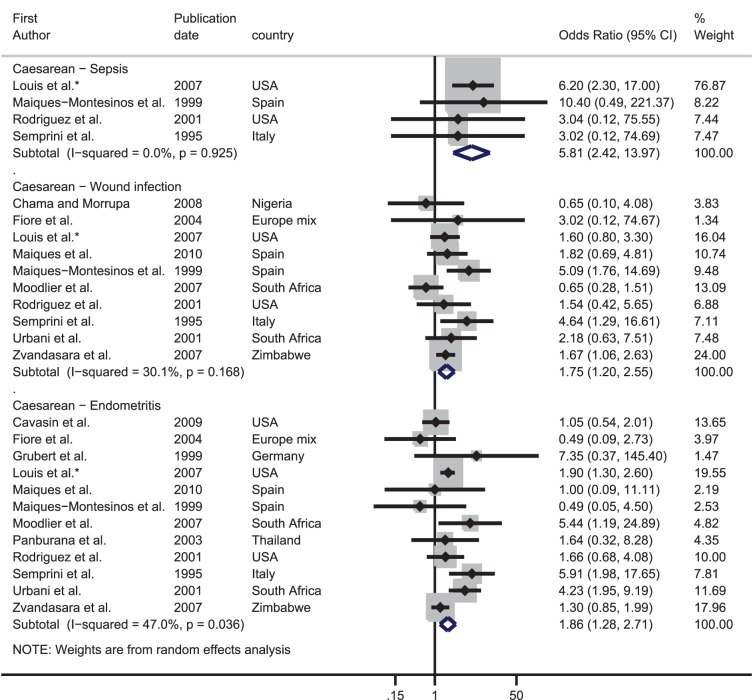

The results of the meta-analyses for women who had a caesarean section are presented in Figure 6. The pooled OR from four data sets indicated that HIV-infected women had nearly six times higher odds of suffering from puerperal sepsis compared with their uninfected counterparts (summary OR 5.81, 95% CI: 2.42–13.97, I2: 0%, p-value = 0.93). Amongst the ten data sets which contained information on wound infection, the pooled OR was 1.75 (95% CI: 1.20–2.55) although there was weak evidence for between-study heterogeneity (I2: 30.1%, p = 0.17). Finally, there were 12 studies which looked at endometritis in HIV-infected and uninfected women; nine found a higher occurrence in HIV-infected women. The meta-analysis showed that HIV-infected women had over double the odds of endometritis than uninfected women (OR: 1.86, 95% CI: 1.28–2.71). There was good evidence for between-study heterogeneity (I2: 47.0%, p = 0.04).

Figure 6. Forest plot showing the strength of association between HIV and intrauterine infection in studies which only looked at caesarean deliveries.

*Adjusted odds ratio.

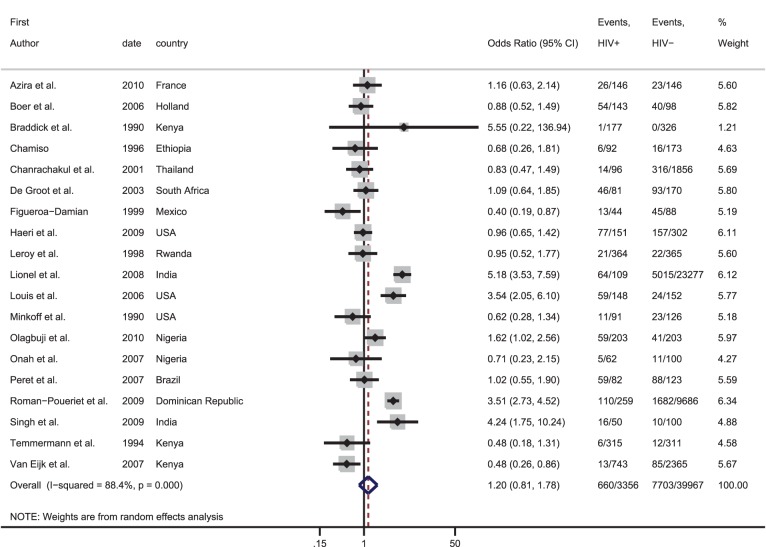

Caesarean section

Of the studies which included vaginal and caesarean section deliveries, 13 did not provide information on the proportion of HIV-infected and uninfected women who had a caesarean (one stated that there was no difference in the mode of delivery in HIV-infected and uninfected women, one was restricted to only vaginal deliveries, three only followed women during pregnancy and eight did not provide any information on the proportion of infected and uninfected women having caesareans). Figure 7 shows the relative odds of having a caesarean for HIV-infected compared with uninfected women across the 19 studies which provided data. The ORs varied from 0.40 to 5.55 and there was no evidence that HIV-infected women were more likely to have a caesarean compared with uninfected women [pooled OR: 1.20, 95% CI: 0.81–1.78]. However, there was strong evidence for between-study heterogeneity (I2: 88.4%, p<0.001).

Figure 7. Forest plot showing the strength of association between HIV and caesarean section in studies included in this systematic review.

Discussion