Abstract

Background

Bupropion and venlafaxine are effective antidepressants with unique pharmacological profiles.

Objectives

The purpose of this meta-analysis was to determine the efficacy, acceptability, and tolerability of bupropion and venlafaxine therapies for adults with major depressive disorder (MDD). The authors searched clinical trials with low risk of bias, performed from January 1985 to February 2013.

Data sources

The searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and Cochrane Controlled Trials Register were conducted in February 2013. Included populations consisted of adult patients with MDD or major depression.

Study eligible criteria, participants, and interventions

Included studies were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing bupropion and venlafaxine in adult patients with MDD and offering endpoint results relevant to: (1) severity of depression; (2) response rate; (3) remission rate; (4) overall discontinuation rate; or (5) discontinuation rate due to adverse events. Limitation of language was not utilized.

Study appraisal and synthesis methods

The abstracts located from the electronic databases were reviewed. The completed reports from pertinent studies were examined, and essential data were extracted. Based on the Cochrane’s bias assessment, risks of bias were assessed. Any study with two risks or more was excluded. Efficacious outcomes included the mean changed scores of rating scales for depression, overall response rates, and overall remission rates. Acceptability was determined by the overall discontinuation rates. The discontinuation rates due to adverse events were the measurement of tolerability. Relative risks (RR) and weighted mean differences or standardized mean differences with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were computed using a random effect model.

Results

A total of 1,117 participants in three RCTs were included. Depression rating scales used in one and two studies were the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and the Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale, respectively. The pooled mean changed scores of the bupropion-treated group were comparable to those of the venlafaxine-treated group with standardized mean differences (95% CI) of 0.05 (−0.16 to 0.26). The overall response and remission rates were similar with the RRs (95% CI) of 0.92 (0.79–1.08) and 0.97 (0.75–1.24), respectively. The pooled overall discontinuation rate and discontinuation rate due to adverse events were not different between groups with the RRs (95% CI) of 1.00 (0.80–1.26) and 0.69 (0.44–1.10), respectively.

Limitations

The small number of RCTs included in the meta-analysis.

Conclusion

According to the limited data obtained from three RCTs, bupropion XL is as effective and tolerable as venlafaxine XR for adult patients with MDD. Further studies in this area should be conducted to confirm these findings.

Keywords: bupropion, venlafaxine, major depressive disorder, acceptability, tolerability, response rate

Background

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)1–3 and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs)4,5 are common agents for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD). However, some MDD patients do not remit despite receiving an adequate dose and duration of SSRIs and TCAs. The response and remission rates of MDD patients treated with SSRIs are 62%–63%6,7 and 38%,8,9 respectively. Those rates for TCAs may be modestly higher (68% and 44%, respectively). In addition, the discontinuation rate due to adverse events might be as high as 13% and 11%–17% for SSRIs and TCAs treatment,10 respectively. The overall discontinuation rates, as a measure of acceptability, in those patients are 27% for SSRIs and 27%–34% for TCAs.10 These high withdrawal rates suggest that a significant proportion of MDD patients cannot accept or cannot tolerate SSRIs or TCAs.

Sexual dysfunction is a common side effect of antidepressant therapy. The overall rate of treatment emergent sexual dysfunction related to antidepressants may be as high as 15%–80%.11–13 Antidepressants increasing serotonergic function have a negative effect on all three phases of the sexual response cycle, including sexual desire, arousal, and orgasm. Therefore, serotonergic antidepressants, especially SSRIs and selective serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, tend to possess the risk of sexual dysfunction. Recent studies suggest that adjunctive treatment with bupropion can improve sexual function in both women and men with SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction.14,15

Bupropion is a dopamine–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. It is effective not only for depressive disorders but also for nicotine dependence16 and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.17 Possibly due to the lack of serotonergic activity,18 it has less propensity to induce sexual dysfunction, weight gain, and a psychological side effect of apathy syndrome19–22 than SSRIs. These adverse events are important because they are the primary reasons of SSRI discontinuation.23

Venlafaxine is a serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor approved for the treatment of MDD patients. This agent is of interest because its efficacy is relatively superior to other antidepressants; eg, SSRIs24,25 and duloxetine.26 However, its discontinuation rate due to adverse events appears to be higher than that of SSRIs.27

Because bupropion has pharmacological and clinical profiles different from most antidepressants and venlafaxine is highly effective, we proposed to carry out a meta-analysis comparing it with venlafaxine in patients with MDD in terms of: efficacy, as measured by pooled mean change scores of depression severity, response, and remission rates; acceptability, as measured by overall discontinuation rate; and tolerability, as measured by discontinuation rate due to adverse events. In addition, sexual dysfunction in both groups was also compared. Only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were included.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

Eligible studies were RCTs comparing bupropion and venlafaxine in MDD patients aged 18–65 years old. Severity of depression was rated at baseline and the end of treatment with a standardized rating scale.28 The rates of response, remission, overall discontinuation, or discontinuation rate due to adverse events were reported. The RCTs with any duration of treatment for major depressive episode, diagnosed by any set of criteria, were included. No language restriction was applied.

Information sources

The searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO and Cochrane Controlled Trials Register databases were conducted in February 2013. In accordance with the MEDLINE search, the earliest publications regarding bupropion and venlafaxine were 1977 and 1985, respectively. Thus, searching for those publications covered the period from 1985 through February 2013. Searching was restricted to adult humans. Additional studies were also searched from the clinical trials registry, including ClinicalTrials.gov, the EU Clinical Trials Register, and the databases of GlaxoSmithKline and Pfizer, producers of the original bupropion and venlafaxine, respectively. The reference of the article given by any method was explored. All accordant RCTs and clinical controlled trials were taken into account.

Searches

To optimize the sensitivity in identification of the randomized clinical trials, the searched strategy for MEDLINE adhered to these words and phrases: “(bupropion) OR (Wellbutrin)” AND “(venlafaxine) OR (Effexor) OR (Efexor)” AND “(major depressive disorder) OR (MDD) OR (major depression)”. Similar search strategies were used for the other databases.

Study selection

To determine if articles conformed to the included criteria defined above, all abstracts searched by electronic databases were independently assessed by the reviewers (NM and BM). After the full-text relevant article was collected, the reviewers then independently examined its eligibility. All disagreements on such eligibility were resolved by a consensus.

Data collection process

After an extraction form of data was generated, the first reviewer (NM) extracted all data into this form. Those extracted data were audited by the second reviewer (BM). Any disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved by consensus. In the event that any disagreement could not be resolved, the fourth author (MS) made a decision.

Data items

Extracted data were acquired from individual studies, including: (1) the essential information used for validity evaluation; (2) basic demographic data of subjects, criteria for diagnosis, study designs, and eligible/ineligible criteria; (3) forms, doses, and period of treatment with bupropion and venlafaxine; (4) interesting results. If possible, the intention-to-treat outcomes were documented.

Risk of bias in individual studies

The assessment of internal validity (quality) of each included study was conducted by two reviewers (NM and BM). According to the Cochrane Collaboration quality assessment, the risk of bias was measured on: (1) sequence generation (randomization); (2) allocation concealment; (3) blinding of participants, personal and outcome; (4) incomplete outcome data; (5) intention-to-treat analysis; (6) selective outcome reporting; and (7) other biases.29 Those risks were categorized by low, high or unclear risk of biases.29 Trials with more than two high risks were excluded from the analysis.

Summary measures

Interesting results comprised efficacy, acceptability, and tolerability. Efficacious measurement depended on the scores of changed mean rated on an MDD scale, and the rate of response was determined by any defined criteria. Although the use of acceptability and tolerability is interchangeable, they each had their own specific definition. According to a recent meta-analysis, this review defined acceptability as measured by the overall discontinuation rate.30 Similar to a previous review, tolerability, which frequently refects the side effects of medications,31 was gathered from the discontinuation rate due to adverse events. Any dichotomous or continuous data relevant to sexual functions were also recorded.

Relative risk (RR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) was applied for synthesis of the discontinuous data. The RR of 1 demonstrates that there were no differences between two groups. For an unexpected result, an RR less than 1, indicated less possibility to obtain this result. In this review, RRs were applied for comparing the rates of response, remission, overall discontinuation, and discontinuation due to adverse events between two groups.

A weighted mean difference (WMD) or standardized mean difference (SMD) is defined as the mean difference between comparison groups that is divided by an estimate of the within-group standard deviation. Mean differences, with 95% CI, were applied for synthesizing the continuous data. If measurement of outcomes used different rating scales across studies, a direct comparison or combination of the study results may be implausible. When the effect is expressed as SMD which has no units, the results can be combined. If the same rating scales were used, a WMD, directly comparing or combining the study results, can be applied. In this meta-analysis, the WMDs or the SMDs were decided to be estimated when the included trials employed similar measured instruments or different measured instruments, respectively. When a standard deviation of a changed mean score was not reported, it was gathered by applying any statistical analysis. If impossible, a direct substitution was used.32

Synthesis of results

Synthesis of data is able to apply either a fixed or random effect model. Based on the fixed effect method, all eligible trials are assumed to contribute a similar effect size, and the variations taking place across studies in this model were ignored. These major concerns could be solved by using a random effect model. In general, the conclusion for one true effect size is practically infeasible. Even if the eligible trials were comparatively homogeneous, we cannot exactly estimate them identically. Consequently, we planned to use a random effect model to synthesize all data in this meta-analysis.

Risk of bias across studies

To assess the reporting bias, a funnel plot, inspecting from each study against some measures of each trial’s size or accuracy,33 was utilized.

Test of heterogeneity

To determine the resemblance of study results, a test of heterogeneity should be applied. While performing this review, we hypothesized that the effect size was different owing to the quality of methodology in each trial. Individual study results were assessed to determine whether they had greater differences than anticipated by chance alone. To evaluate these results, we observed them shown as graphical display and also used the test of heterogeneity. When an I2 of 50% or more was noted, the results were acknowledged as a significance of heterogeneity.

Statistical software

The RevMan 5.1 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark) was applied for all analyses in this meta-analysis.

Results

Study selection

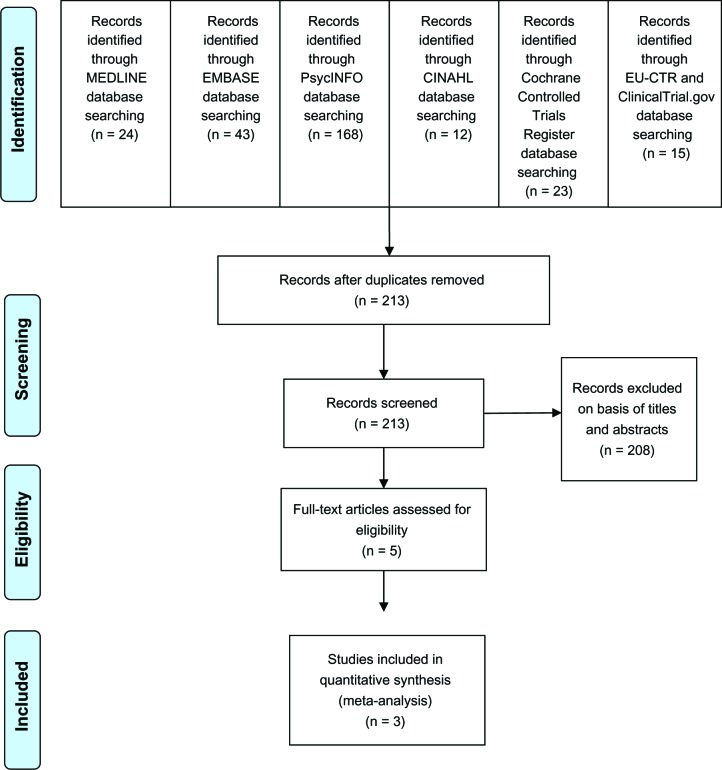

The database searches obtained a total of 285 results (MEDLINE, 24; EMBASE, 43; PsycINFO, 168; CINAHL, 12; Cochrane Controlled Trials Register, 23; EU Clinical Trials Register, 3; ClinicalTrials.gov, 12) (see Figure 1). When duplicates were removed, only 213 studies remained. After checking their titles and abstracts, 208 studies were excluded due to clearly not fitting the eligibility criteria. Three study reports obtained from the database of GlaxoSmithKline34–36 were reviewed. Finally, full papers of eight studies were examined.34–41 Of these, three were duplicates, two were excluded because one was carried out in MDD patients not responding to an SSRI and had a high risk of bias,38 and the other was a trial of the elderly population.39 A total of three studies, therefore, were taken into account in this meta-analysis. Relevant or unpublished trials meeting the eligible criteria were not found.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study.

Abbreviation: E-CTR, Eropean Clinical Trials Register.

Study characteristics

The study duration for the three included studies was between 14 to16 weeks, including up to 2 weeks of screening, 8–12 weeks of treatment, up to 3 weeks of taper phases, and up to 3 weeks of follow-up. All subjects were randomized at baseline to receive either bupropion or venlafaxine. The mean 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D-17), 18-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D-18), and Clinical Global Impression-Severity (CGI-S) scores at baseline were similar across the three studies (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Important characteristics of controlled trials of bupropion versus venlafaxine in major depressive disorder

| Study | Number of patients | Age of subjects (years) | Study duration (weeks) | Drug/dose | Diagnostic criteria | Included criteria | Response criteria | Remission criteria | Outcome measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thase37 | 342 | 18 or more | 15–16 | Bupropion XL*/150 mg/day and 450 mg/day Venlafaxine XR**/75–225 mg/day |

DSM IV-TR | HAM-D-17 ≥ 17 and CGI-S ≥4 | ≥50% reduction in HAM-D-17 | HAM-D-17 ≤7 | HAM-D-17, CGI-S, CGI-I, CSFQ |

| Hewett40 | 374 | 18–64 | 14 | Bupropion XL*/150 mg/day and 300 mg/day Venlafaxine XR**/75–150 mg/day |

DSM IV | HAM-D-18 ≥ 17 and CGI-S ≥4 | ≥50% reduction in MADRS | MADRS ≤ 11 | MADRS, CGI-S, CGI-I, HAM-A MEI, Q-LES-Q-SF, SDS, CSFQ |

| Hewett41 | 401 | 18–64 | Up to 14 | Bupropion XL*/150 mg/day and 300 mg/day Venlafaxine XR**/75–150 mg/day |

DSM IV | HAM-D-18 ≥ 17 and CGI-S ≥4 | ≥50% reduction in MADRS | MADRS ≤ 11 | MADRS, CGI-S, CGI-I, HAM-A MEI, Q-LES-Q-SF, SDS, CSFQ |

Notes:

Wellbutrin XR®, GlaxoSmithKline, London, UK

Effexor XR®, Wyeth-Ayers, Philidelphia, PA, USA.

Abbreviations: CGI-I, Clinical Global Impression-Improvement scale; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impression-Severity of Illness; CSFQ, Changes in Sexual Functioning Questionnaire; DSM IV-TR, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders fourth edition text revision; HAM-A, Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety; HAM-D-17, 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; HAM-D-18, 18-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; MADRS, Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale; MEI, 18-item Motivation and Energy Inventory; Q-LES-Q-SF, Short Form Quality of Life Enjoyment Satisfaction Questionnaire; SDS, Sheehan Disability Scale.

Of 1,117 participants, 65.6% were female (see Table 1). All participants were patients with MDD. Mean (standard deviation) ages of the bupropion and venlafaxine groups were 41.83±12.36 years and were 41.62±11.87 years, respectively. All subjects in the included trials were treated with bupropion XL or venlafaxine XR. The doses of bupropion XL (Wellbutrin XR®, GlaxoSmithKline, London, UK) and venlafaxine XR (Effexor XR®, Wyeth-Ayerst, Philadelphia, PA, USA) ranged from 150 mg/day to 450 mg/day and 75 mg/day to 225 mg/day, respectively. Table 1 shows the basic characteristics of eligible trials.

Regarding depression severity, two studies reported the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MARDS) scores, and the other reported the HAM-D-17 scores. SMDs of the mean changed scores were calculated and synthesized. Because all three trials used the Changes in Sexual Functioning Questionnaire (CSFQ), the WMDs of mean changed CSFQ score were, therefore, estimated and synthesized.37,40,41 All trials presented the rates of remission, response, overall discontinuation and discontinuation due to adverse events.

Risk of bias within studies

The randomized technique, double blindness, and an intention-to-treat analysis were applied in all trials. Dropouts and similarity of baseline were presented in all trials. None of the trials presented a generated sequence for randomization and allocation concealment. The risk of bias for baseline similarity was not observed (see Table 2). Since all trials had the low-risk of biases, all their data were analyzed.

Table 2.

Risk of bias summary of controlled trials of bupropion versus venlafaxine in major depressive disorder

| Study | Issues of bias

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

| Thase37 | U | L | L | L | U | L | L | L |

| Hewett40 | U | L | L | L | U | L | L | L |

| Hewett41 | U | L | L | L | U | L | L | L |

Notes: 1 = Adequate sequence generation; 2 = Allocation concealment; 3 = Blinding (subjective outcome); 4 = Dropout data addressed; 5 = Free of selective reporting; 6 = Free of other bias; 7 = Baseline similarity; 8 = Itention-to-treat analysis or modifed intention-to-treat analysis.

Abbreviations: L, low risk of bias; U, unclear risk of bias.

Results of individual studies

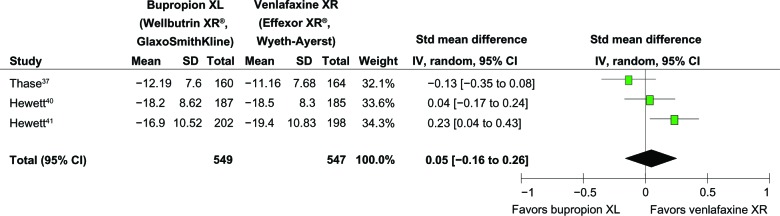

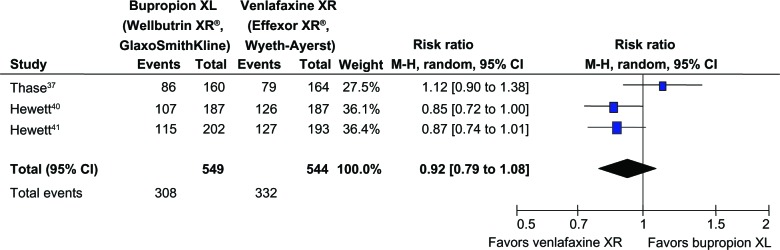

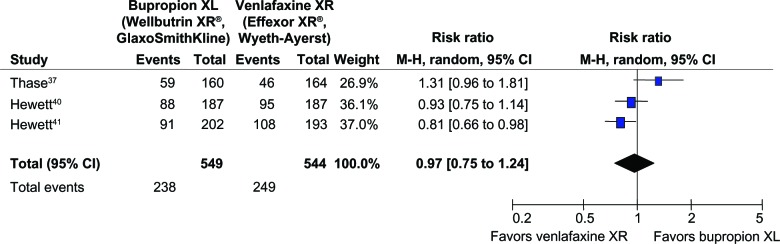

The mean changed HAM-D-17, HAM-D-18, or MADRS scores of both groups in each study was not significantly different (see Figure 2). The rates of response and remission between the bupropion- and venlafaxine-treated groups in individual trials were comparable (see Figures 3 and 4). In addition, the mean changed CSFQ scores of the bupropion- and venlafaxine-treated groups in individual trials had no significant differences (see Figure 5).

Figure 2.

Comparison of the mean changes from baseline of depression rating scales (95% confidence interval) in patients with MDD: bupropion versus venlafaxine.

Notes: Heterogeneity: Tau2 = 0.02; Chi2 = 6.11; df = 2 (P = 0.05); I2 = 67%. Test for overall effect: Z = 0.46 (P = 0.64).

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; IV, inverse variance; MDD, major depressive disorder; SD, standard deviation; Std, standard; df, degrees of freedom.

Figure 3.

Comparison of relative risk (95% confidence interval) for clinical response rates in patients with MDD: bupropion versus venlafaxine.

Notes: Heterogeneity: Tau2 = 0.01; Chi2 = 4.65; df = 2 (P = 0.10); I2 = 57%. Test for overall effect: Z = 1.04 (P = 0.30).

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel; MDD, major depressive disorder.

Figure 4.

Comparison of relative risk (95% confidence interval) for clinical remission rates in patients with MDD: bupropion versus venlafaxine.

Notes: Heterogeneity: Tau2 = 0.03; Chi2 = 6.70, df = 2 (P = 0.04); I2 = 70%. Test for overall effect: Z = 0.27 (P = 0.79).

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel; MDD, major depressive disorder.

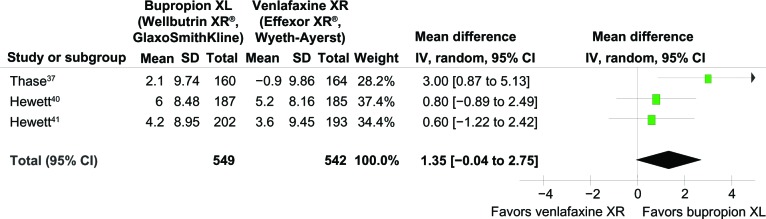

Figure 5.

Comparison of the mean changes from baseline of the CSFQ (95% confidence interval) in patients with MDD: bupropion versus venlafaxine.

Notes: Heterogeneity: Tau2 = 0.61; Chi2 = 3.34, df = 2 (P = 0.19); I2 = 40%. Test for overall effect: Z = 1.90 (P = 0.06).

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom; CSFQ, Changes in Sexual Functioning Questionnaire; IV, inverse variance; MDD, major depressive disorder; SD, standard deviation.

Synthesis of results

Efficacy

Significant heterogeneity was observed in the SMDs of depression severity, the response rates, and the remission rates. The pooled SMD of depression severity had no significant differences between groups (SMD [95% CI] of 0.05 [−0.16 to 0.26], I2 = 67%) (see Figure 2). The pooled response rate was comparable (RR [95% CI] of 0.92 [0.79 to 1.08], I2 = 57%) (see Figure 3). The pooled remission rate of the two groups had also no significant difference between groups (RR [95% CI] of 0.97 [0.75 to 1.24], I2 = 70%) (see Figure 4). Although there was a trend of superiority for bupropion on sexual function, the pooled mean changed CSFQ scores of the two groups was also not significantly different (WMD [95% CI] of 1.35 [−0.04 to 2.75], I2 = 40%) (see Figure 5).

Discontinuation rates

Both discontinuation rates had no significant heterogeneity. The pooled overall discontinuation rate of the bupropion and venlafaxine groups was comparable (RR [95% CI] of 1.0 [0.80 to 1.26], I2 = 26%). The pooled discontinuation rate due to adverse events in the bupropion-treated group was not significantly greater than that of the venlafaxine-treated group (RR [95% CI] of 0.69 [0.44 to 1.10], I2 = 0%).

Risk of bias across studies

For a meta-analysis of nine RCTs or less, a funnel plot for the testing of publication bias may not have enough power to detect a chance of real asymmetry occurred by included results.33 Hence, a test of funnel plot was not performed since only three trials were taken in this review.

Discussion

This meta-analysis identified only three randomized controlled trials of bupropion compared with venlafaxine. All participants were adult patients with MDD. Two of the three studies had the same study designs.34,35,40,41 The outcomes of this review demonstrate that 150–450 mg/day of bupropion XL is as effective as 75–225 mg/day of venlafaxine in the MDD treatment. No difference of discontinuation rates due to adverse events or overall discontinuation rates suggests that both the tolerability and acceptability of both agents were comparable. Although there was a trend of superiority for bupropion with regard to sexual function, the pooled mean changed CSFQ scores of the two groups were still not significantly different.

The comparable efficacy and acceptability of bupropion and venlafaxine found in this meta-analysis should be viewed with caution. While venlafaxine appears to be superior to SSRIs (Stahl et al 2002;42 and Papakostas et al 200743), bupropion may not be the same. A previous meta-analysis of seven RCTs comparing bupropion (n = 748) and SSRIs (n = 758) showed that bupropion and SSRIs were superior to placebo and had similar remission rates at week 8 (47% for both). While the present findings support the comparable acceptability of bupropion and venlafaxine, venlafaxine has been found to be less acceptable than SSRI.27 Another study found that bupropion and SSRIs may have similar acceptability, with dropout rates of 59% and 55%, respectively.44 These conflicting results may suggest that the efficacy and acceptability of bupropion are somewhere between those of SSRIs and venlafaxine. More clinical trials comparing bupropion and venlafaxine are therefore warranted to determine the efficacy and acceptability of bupropion as compared with other antidepressants.

Treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction related to antidepressants is a common problem in clinical practice. This problem may complicate the adherence to antidepressant treatment. Sexual dysfunction may be as high as 80% in MDD patients treated with antidepressants. Compared with placebo, higher percentages of sexual dysfunction are associated with citalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, and venlafaxine. Antidepressant therapies with a lower prevalence of sexual dysfunction may consist of amineptine, agomelatine, bupropion, mirtazapine, moclobemide, and nefazodone.11 Similarly, a meta-analysis of seven RCTs suggested that SSRI-treated patients had a greater rate of sexual dysfunction than patients treated with bupropion and placebo.45 Possibly due to the small sample size, only the trend of superiority in this respect can be found in the bupropion-treated group.

This meta-analysis had a number of limitations. Initially, the measures of depression severity were different among the included trials. Although one of trials used the HAM-D-17 scale, the other two used the MADRS scale. The response rates, the remission rate, and the severity of depression derived from these scales were therefore varied across the studies. Secondly, this review took in account only three RCTs funded by a patent holding company for bupropion XL. Hence, the findings should be considered as rudimentary outcomes and interpreted with caution. Thirdly, although all included trials were categorized as low risk, they did not report a sequence of generation and blinding adequately. Finally, due to the small number of eligible trials, a funnel plot test to evaluate asymmetry could not be applied.33 The publication bias in this matter, therefore, could not be excluded.

Conclusion

According to the findings provided from these three RCTs, bupropion XL was as effective as venlafaxine XR for adult MDD patients. The equivalent dropout rate due to adverse events indicates the comparable tolerability of both active agents. Based on the overall discontinuation rates, which took into account both the efficacious benefit and risk from adverse events, these agents appeared to have comparable acceptability. Based on the CSFQ scores, a trend indicated that bupropion is less likely to cause treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction. However, these outcomes should be considered as initial findings. Further well-defined clinical trials in this field should be conducted to confirm these findings. Additionally, further systemic reviews of bupropion in the treatment of MDD compared with other antidepressants, including SSRIs, may be useful.

Acknowledgments

All authors conceptualized the idea, developed the review protocol, prepared the manuscript for publication, and affirmed the manuscript in its current form. NM and BM searched articles from the databases, extracted the data, and analyzed the data.

Footnotes

Disclosure

NM and BM received travel honoraria and/or travel reimbursement from GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, and Lundbeck. KE reports no conflict of interest in this paper. MS received honoraria, consultancy fees, research grants, and/or travel reimbursement from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Janssen-Cilag, Johnson and Johnson, Lundbeck, Thai-Otsuka, Sanofii-Aventis, and Servier. There was no financial support for this meta-analysis. The authors report no further conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Bech P, Cialdella P, Haugh MC, et al. Meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of fluoxetine v. placebo and tricyclic antidepressants in the short-term treatment of major depression. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:421–428. doi: 10.1192/bjp.176.5.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Papakostas GI, Charles D, Fava M. Are typical starting doses of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors sub-optimal? A meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-finding studies in major depressive disorder. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2010;11(2 Pt 2):300–307. doi: 10.3109/15622970701432528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Geddes JR, et al. MANGA Study Group Does randomized evidence support sertraline as first-line antidepressant for adults with acute major depression? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(11):1732–1742. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Furukawa TA, McGuire H, Barbui C. Meta-analysis of effects and side effects of low dosage tricyclic antidepressants in depression: systematic review. BMJ. 2002;325(7371):991. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7371.991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Furukawa T, McGuire H, Barbui C. Low dosage tricyclic antidepressants for depression [review] Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(3):CD003197. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steffens DC, Krishnan KR, Helms MJ. Are SSRIs better than TCAs? Comparison of SSRIs and TCAs: a meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 1997;6(1):10–18. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6394(1997)6:1<10::aid-da2>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Papakostas GI, Homberger CH, Fava M. A meta-analysis of clinical trials comparing mirtazapine with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for the treatment of major depressive disorder. J Psychopharmacol (Oxford) 2008;22(8):843–848. doi: 10.1177/0269881107083808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Machado M, Iskedjian M, Ruiz I, Einarson TR. Remission, dropouts, and adverse drug reaction rates in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of head-to-head trials. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22(9):1825–1837. doi: 10.1185/030079906X132415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thase ME, Pritchett YL, Ossanna MJ, Swindle RW, Xu J, Detke MJ. Efficacy of duloxetine and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: comparisons as assessed by remission rates in patients with major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27(6):672–676. doi: 10.1097/jcp.0b013e31815a4412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson IM. Meta-analytical studies on new antidepressants. Br Med Bull. 2001;57:161–178. doi: 10.1093/bmb/57.1.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Serretti A, Chiesa A. Treatment-emergent sexual dysfunction related to antidepressants: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;29(3):259–266. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181a5233f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams VS, Edin HM, Hogue SL, Fehnel SE, Baldwin DS. Prevalence and impact of antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction in three European countries: replication in a cross-sectional patient survey. J Psychopharmacol (Oxford) 2010;24(4):489–496. doi: 10.1177/0269881109102779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strohmaier J, Wüst S, Uher R, et al. Sexual dysfunction during treatment with serotonergic and noradrenergic antidepressants: clinical description and the role of the 5-HTTLPR. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2011;12(7):528–538. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2011.559270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Safarinejad MR. Reversal of SSRI-induced female sexual dysfunction by adjunctive bupropion in menstruating women: a double-blind, placebo-controlled and randomized study. J Psychopharmacol (Oxford) 2011;25(3):370–378. doi: 10.1177/0269881109351966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Safarinejad MR. The effects of the adjunctive bupropion on male sexual dysfunction induced by a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor: a double-blind placebo-controlled and randomized study. BJU Int. 2010;106(6):840–847. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.09154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eisenberg MJ, Filion KB, Yavin D, et al. Pharmacotherapies for smoking cessation: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. CMAJ. 2005;179(2):135–144. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.070256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maneeton N, Maneeton B, Srisurapanont M, Martin SD. Bupropion for adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;65(7):611–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2011.02264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stahl SM, Pradko JF, Haight BR, Modell JG, Rockett CB, Learned-Coughlin S. A Review of the Neuropharmacology of Bupropion, a Dual Norepinephrine and Dopamine Reuptake Inhibitor. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;6(4):159–166. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v06n0403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoehn-Saric R, Lipsey JR, McLeod DR. Apathy and indifference in patients on fluvoxamine and fluoxetine. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1990;10(5):343–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Opbroek A, Delgado PL, Laukes C, et al. Emotional blunting associated with SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction. Do SSRIs inhibit emotional responses? Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002;5(2):147–151. doi: 10.1017/S1461145702002870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee SI, Keltner NL. Antidepressant apathy syndrome. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2005;41(4):188–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6163.2005.00033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Demyttenaere K, Jaspers L. Review: Bupropion and SSRI-induced side effects. J Psychopharmacol (Oxford) 2008;22(7):792–804. doi: 10.1177/0269881107083798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bolling MY, Kohlenberg RJ. Reasons for quitting serotonin reuptake inhibitor therapy: paradoxical psychological side effects and patient satisfaction. Psychother Psychosom. 2004;73(6):380–385. doi: 10.1159/000080392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmitt AB, Bauer M, Volz HP, et al. Differential effects of venlafaxine in the treatment of major depressive disorder according to baseline severity. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;259(6):329–339. doi: 10.1007/s00406-009-0003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schueler YB, Koesters M, Wieseler B, et al. A systematic review of duloxetine and venlafaxine in major depression, including unpublished data. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2011;123(4):247–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eckert L, Lançon C. Duloxetine compared with fluoxetine and venlafaxine: use of meta-regression analysis for indirect comparisons. BMC Psychiatry. 2006;6:30. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-6-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Silva VA, Hanwella R. Efficacy and tolerability of venlafaxine versus specific serotonin reuptake inhibitors in treatment of major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of published studies. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;27(1):8–16. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e32834ce13f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uher R, Farmer A, Maier W, et al. Measuring depression: comparison and integration of three scales in the GENDEP study. Psychol Med. 2008;38(2):289–300. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC, editors; Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. Version 5.1.0 (updated Mar 2011) Available from: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation antidepressants: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373(9665):746–758. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Papakostas GI. Tolerability of modern antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(Suppl E1):8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wiebe N, Vandermeer B, Platt RW, Klassen TP, Moher D, Barrowman NJ. A systematic review identifes a lack of standardization in methods for handling missing variance data. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59(4):342–353. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chapter 10: Addressing reporting biases. In: Sterne JAC, Egger M, Moher D, editors; Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011) Available from: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org. [Google Scholar]

- 34.GlaxoSmithKline A multi-centre, randomised, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo- and active-controlled, fexible dose study evaluating the efficacy, safety and tolerability of extended-release bupropion hydrochloride (150 mg–300 mg once daily), extended-release venlafaxine hydrochloride (75 mg–150 mg once daily) and placebo in subjects with major depressive disorder Available from http://www.gsk-clinicalstudyregister.com/result_detail.jsp?protocolId=AK130939&studyId=7A3E0BD4-A282-4F67-AB1F-FFC9B215D730&compound=bupropion&type=Compound&letterrange=A-FDate accessed February 2, 2013

- 35.GlaxoSmithKline A multi-centre, randomised, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo- and active-controlled, fexible dose study evaluating the efficacy, safety and tolerability of extended-release bupropion hydrochloride (150 mg–300 mg once daily), extended-release venlafaxine hydrochloride (75 mg–150 mg once daily) and placebo in subjects with major depressive disorder Available from http://www.gsk-clinicalstudyregister.com/result_detail.jsp?protocolId=101497&studyId=F54FA1DC-4F87-46AF-A8DA-BFEBFCF170B7&compound=bupropion&type=Compound&letterrange=A-FDate accessed February 2, 2013

- 36.GlaxoSmithKline A twelve-week, multi-center, randomized, doubleblind, double-dummy, parallel-group, active-controlled, escalating dose study to compare the effects on sexual functioning of bupropion hydrochloride extended-release (WELLBUTRIN® XL, 150–450 mg/day) and extended-release venlafaxine (effexor XR, 75–225 mg/day) in subjects with major depressive disorder Available from http://www.gsk-clinicalstudyregister.com/result_detail.jsp?protocolId=100368&studyId=A5B5F2C5-6C67-40EC-9476-DFAA38338F84&compound=bupropion&type=Compound&letterrange=A-F. NCT00316160Date accessed February 2, 2013

- 37.Thase ME, Clayton AH, Haight BR, Thompson AH, Modell JG, Johnston JA. A double-blind comparison between bupropion XL and venlafaxine XR: sexual functioning, antidepressant efficacy, and tolerability. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;26(5):482–488. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000239790.83707.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. STAR*D Study Team Bupropion-SR, sertraline, or venlafaxine-XR after failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(12):1231–1242. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hewett K, Chrzanowski W, Jokinen R, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled evaluation of extended-release bupropion in elderly patients with major depressive disorder. J Psychopharmacol (Oxford) 2010;24(4):521–529. doi: 10.1177/0269881108100254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hewett K, Chrzanowski W, Schmitz M, et al. Eight-week, placebo-controlled, double-blind comparison of the antidepressant efficacy and tolerability of bupropion XR and venlafaxine XR. J Psychopharmacol (Oxford) 2009;23(5):531–538. doi: 10.1177/0269881108089602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hewett K, Gee MD, Krishen A, et al. Double-blind, placebo-controlled comparison of the antidepressant efficacy and tolerability of bupropion XR and venlafaxine XR. J Psychopharmacol (Oxford) 2010;24(8):1209–1216. doi: 10.1177/0269881109106953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stahl SM, Entsuah R, Rudolph RL. Comparative efficacy between venlafaxine and SSRIs: a pooled analysis of patients with depression. Biological psychiatry. 2002 Dec 15;52(12):1166–1174. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01425-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Papakostas GI, Thase ME, Fava M, Nelson JC, Shelton RC. Are antide-pressant drugs that combine serotonergic and noradrenergic mechanisms of action more effective than the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in treating major depressive disorder? A meta-analysis of studies of newer agents. Biological psychiatry. 2007 Dec 1;62(11):1217–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gartlehner G, Hansen RA, Carey TS, Lohr KN, Gaynes BN, Randolph LC. Discontinuation rates for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and other second-generation antidepressants in outpatients with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;20(2):59–69. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200503000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thase ME, Haight BR, Richard N, et al. Remission rates following antidepressant therapy with bupropion or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a meta-analysis of original data from 7 randomized controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(8):974–981. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]