Abstract

Background

The provision of complementary therapy in palliative care is rare in Canadian hospitals. An Ontario hospital's palliative care unit developed a complementary therapy pilot project within the interdisciplinary team to explore potential benefits. Massage, aromatherapy, Reiki, and Therapeutic Touch™ were provided in an integrated approach. This paper reports on the pilot project, the results of which may encourage its replication in other palliative care programs.

Objectives

The intentions were (1) to increase patients'/families' experience of quality and satisfaction with end-of-life care and (2) to determine whether the therapies could enhance symptom management.

Results

Data analysis (n=31) showed a significant decrease in severity of pain, anxiety, low mood, restlessness, and discomfort (p<0.01, 95% confidence interval); significant increase in inner stillness/peace (p<0.01, 95% confidence interval); and convincing narratives on an increase in comfort. The evaluation by staff was positive and encouraged continuation of the program.

Conclusions

An integrated complementary therapy program enhances regular symptom management, increases comfort, and is a valuable addition to interdisciplinary care.

Introduction

The provision of complementary therapy in palliative care is rare in Canadian hospitals. Mackenzie Richmond Hill Hospital (MRHH) is a community hospital north of Toronto, with a 15-bed inpatient palliative care unit established in 2000 within Complex Continuing Care. In 2010 the MRHH Foundation funded an integrated complementary therapy pilot program. This brief account reports on the project, the results of which may encourage its replication in other palliative care programs.

Methods

The Leadership Team of Complex Continuing Care had overall responsibility, while the Complementary Therapy Consultant (CTC) led day-to-day operations. The CTC was both hands on and responsible for recruiting, training, and managing Volunteer Complementary Therapists (VCTs). A Volunteer Position Description, Standard of Practice, and Guidelines for Selection, Supervision and Support of VCTs were developed, as well as an operational framework. Complementary therapists were recognized practitioners and members of the professional association for the key therapy practiced.

MRHH model

Aromatherapy and massage, Reiki, and Therapeutic Touch™ were provided. Table 1 gives information on these therapies.1,2 In line with the hospital's fragrance-free policy, the use of aromatherapy was guided by an agreed standard of practice.

Table 1.

Aromatherapy, Reiki, and Therapeutic Touch™

| Aromatherapy in palliative care uses essential oils in two ways—first, diluted in carrier oils for massage which aims to enhance psychological and physical well-being and increase comfort, and secondly, in ointments, creams, and mouth care preparations for certain symptoms. |

| Reiki is a Japanese word for universal life-force energy. Reiki is a Japanese light-touch, energy-based modality during which the practitioner supports a reestablishment of a natural energy flow throughout the patient's body.1 Reiki is said to enhance the body's natural healing ability.1 |

| Therapeutic Touch™ is described as a directed process of energy exchange during which practitioners use their hands as a focus to facilitate healing.2 Therapeutic Touch™ does not require the practitioner to touch the patient. |

A therapeutic relationship3 and the skillful use of touch were integral to the program. ‘Skillful touch’ is said to stimulate self-awareness and restore to the patient some sense of control and balance in a seemingly powerless situation.4,5 VCTs were taught to provide simple massage and received supervision from the CTC to support the development of the therapeutic relationship.

The North American consensus definition of spirituality states, “Spirituality is the aspect of humanity that refers to the way individuals seek and express meaning and purpose, and the way they experience their connectedness to the moment, to self, to others, to nature, and to the significant or sacred.”6 It has been said that staff in a palliative care team are responsible for providing psychological support and spiritual care at the level of their role and competence.7 In the relaxed atmosphere of complementary therapy sessions, patients often expressed emotions and asked ‘seeking’ questions. Complementary therapists listened and responded supportively. Table 2 outlines the MRHH integrated model.

Table 2.

A Model for an Integrated and Holistic Complementary Therapy Program

| • A therapeutic relationship |

| • Aromatherapy: (1) aromatherapy massage and (2) aromatherapy products |

| • Reiki and Therapeutic Touch™ |

| • Complementary therapists practicing more than one modality, including simple massage |

| • Spiritual care |

| • Emotional support |

| • Access to brief medical and social history of patients |

| • Documentation/charting |

| • Interdisciplinary team meetings |

| • Supervision and support for VCTs |

Volunteer Complementary Therapist, VCT.

Patient assessment and interventions

Background information was obtained prior to approaching a patient, including brief medical and social histories, reasons for admission, current condition, and any family/social issues of concern. In general, patients/families had not experienced complementary therapy and time was given to build rapport. It was explained how massage/aromatherapy, Reiki, and Therapeutic Touch™ may help to promote relaxation, ease discomfort, or simply be something pleasurable. Patients were screened for allergies to skin care products. Families were taught simple hand and foot massage when possible.

Aromatherapy products8 were made to enhance symptom management when appropriate. Table 3 shows the variety of aromatherapy products that were made in a room that was designated for this purpose.

Table 3.

Aromatherapy Products

| • Massage or aromatherapy massage oil |

| • Mouth care products, e.g., aromatherapy mouth care solution for dry mouth, aloe vera gel for dry lips, aromatherapy mouth care solution for malodor or pain in the mouth. |

| • Aromatherapy ointment for red, inflamed, and/or painful intact skin |

| • Aromatherapy moisturizing cream for dry and/or itchy skin |

| • Aromastick inhaler for breathlessness and/or anxiety |

| All aromatherapy products were labeled with the patient's name, what the product was to be used for, ingredients, batch number, and expiration date. |

Complementary therapists responded supportively if a patient/family ‘opened up.’ This level of interaction was often sufficient, but the interdisciplinary team decided whether follow-up was required by the social work or spiritual care teams. Two examples of psychospiritual supportive care are given in Tables 4 and 5.

Table 4.

Psychospiritual Supportive Care (a)

| Henry, 75, was admitted with metastatic prostate cancer and spinal cord compression. He was bedbound, otherwise alert, orientated, and had a good appetite. He felt that if he could not go home, there was no purpose to living. He loved having his lower legs massaged but he could not relax and talked throughout the session, ending with the lament, “What is the point?!” No amount of talking or massage seemed to ease his anguish. At the third session his wife, son, and daughter were present and when he continued to lament, “What is the point?! What is the point?!” the complementary therapist replied, “Henry, you have said this many times. It sounds like life feels very dark and dire to you. When life feels so dire, what is most important to you?” He replied immediately, “My family! Spending time with my family, having my family around me.” At this point his son turned to the window with tears in his eyes. Henry continued to talk about how important his family was to him, and the complementary therapist left Henry with his family. Henry's daughter followed the complementary therapist out and said, “Thank you. You have no idea how important it was for us to hear Dad say that.” This was a turning point for Henry and his family. |

Table 5.

Psychospiritual Supportive Care (b)

| Martha, 62, was admitted with rectal carcinoma and a newly formed colostomy. She was withdrawn, did not communicate except monosyllabically, and refused to learn to look after her colostomy. She always wanted a massage but did not communicate other than to stare at the complementary therapist or television throughout the session. After several weeks, and during a massage, one complementary therapist asked Martha if she really wanted massage, as she did not seem to be enjoying it at all. The therapist assured Martha that she did not need to consent to massage to ‘please the complementary therapist,’ but Martha insisted that she wanted massage. A week later, a second complementary therapist, having built a relationship with Martha over several weeks, continued to gently pursue the theme of the benefits of massage for Martha. Gently and during the course of the massage (and while Martha was continuing to stare) the therapist asked Martha if she could let her know, for evaluation purposes, how massage helped her. Martha said, “It helps me relax.” The complementary therapist then asked Martha, “If you could use a word other than relax, what word would you use?” When Martha said “therapeutic,” the complementary therapist continued to gently probe, “In what way?” Martha remained silent and stared at the ceiling for a long time (while the massage continued), and when the complementary therapist finally reminded her by simply saying “Hello?” Martha blurted out, “My legs feel wonderful afterwards.” After 10 weeks, an expression of emotion from Martha, a breakthrough which eventually lead to her discharge home for several months. |

Evaluation

Data was collected on admissions, the number who received complementary therapy interventions, and sessions that included psychospiritual supportive care. Patients/families were asked to complete a simple questionnaire after one or two sessions—the questions were based on a study with patients with cancer that identified symptoms with which complementary therapy helped.9 A visual analogue scale was used for before and after scores and narrative comments were invited. Staff completed a questionnaire.

Results

The general data showed that 86% of patients admitted had received complementary therapy interventions, and 69% of sessions had included a degree of psychospiritual support. Aromatherapy products shown in Table 3 were routinely used.

Patient/family evaluation

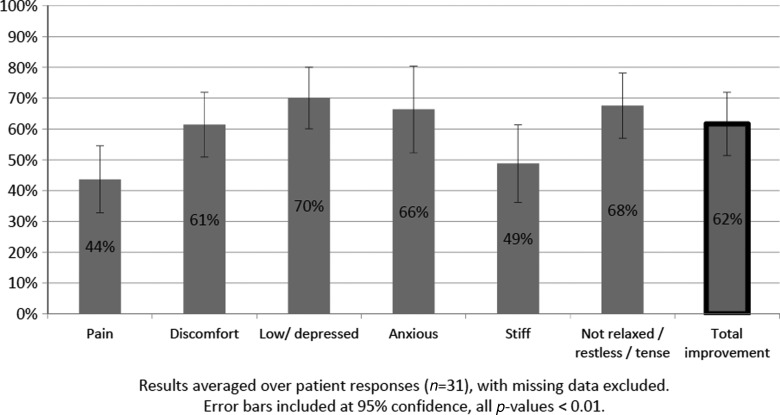

Table 6 shows the symptoms that were problematic for 45% or more patients. Patients were asked to rate the severity of each symptom before and after one or two sessions. A visual analogue scale from 0 to 10 was used, with 0=as good as it can be and 10=as bad as it can be. Figure 1 shows the percent improvement. Percent improvement was measured by comparing the before and after responses. It was calculated by dividing the change in symptom level by the largest possible improvement. Results were averaged over a subset of n=31 respondents (missing data excluded). The total improvement for each patient was the average of the percent improvement across each symptom. A standard paired sample t test was conducted for each symptom and the total improvement for each patient; the p-values were all less than 0.01, indicating that the percent improvements were all significant, with 95% confidence.

Table 6.

Which of These Symptoms Are a Problem for You?

| Symptom | Percent of patients |

|---|---|

| Pain | 45% |

| Discomfort | 70% |

| Low/depressed | 65% |

| Anxiety | 65% |

| Stiff | 50% |

| Not relaxed/restless/tense | 75% |

FIG. 1.

Average percent decrease in symptoms.

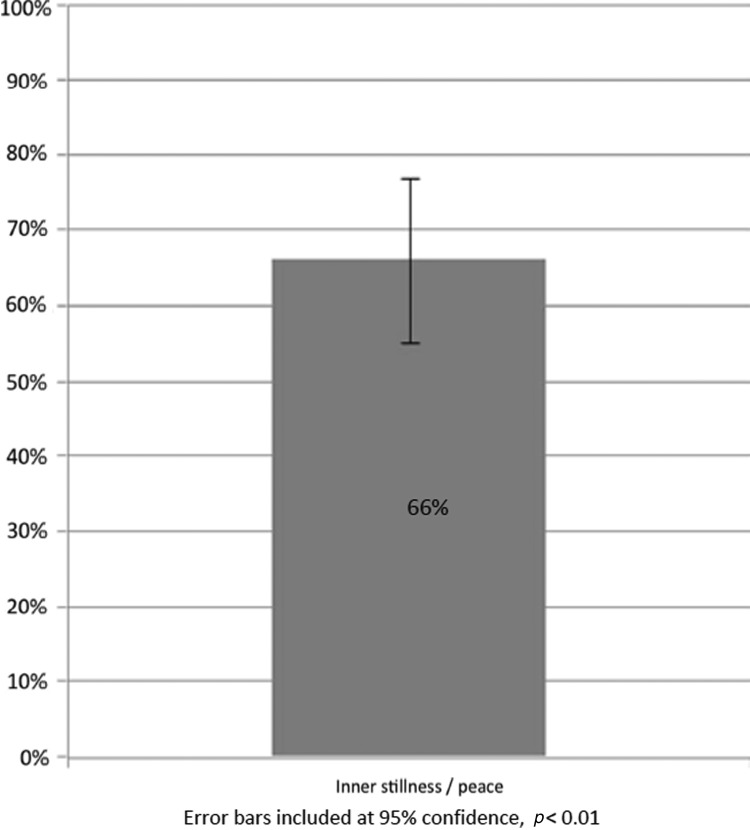

Patients were asked whether inner stillness/peace was relevant for them and if so, to rate their perception of inner stillness/peace before and after one or two sessions. Again a visual analogue scale was used, with 0=as bad as it can be, and 10=as good as it can be. Table 7 and Figure 2 show the results.

Table 7.

Is Inner Stillness / Peace Relevant to You?

| Percent of patients | |

|---|---|

| Yes, relevant | 80% |

| No, not relevant | 20% |

FIG. 2.

Percent increase in inner stillness/peace.

The questionnaire invited narrative comments from patients/families. The word “calm” was used most often to describe how patients felt or appeared to their family after a session, when previously they had been “anxious,” “fearful,” “irritable,” “restless,” “stressed,” or in “pain.” One family commented that their father was “able to deal with discomfort with greater ease.” Another patient stated that “it put me in touch with my deeper self.” Aromatherapy products were said to be “small but important” measures bringing “significant comforts,” relieving dry or painful skin or a dry mouth, and allowing families to participate in the care of their loved ones. The “unhurried way” of the complementary therapists was said to make patients feel “special,” that “somebody cares,” and that a “holistic” dimension was added to care.

Staff evaluation

The feedback from the chief palliative care physician noted favorable results:

The level of satisfaction of patients and families has been absolutely amazing—not only regarding symptom control, but the level of comfort and peace. The complementary therapist is able to listen to their inner worries and concerns, which has really helped to support the work of the rest of the team. And at our weekly rounds she is a valuable resource.

The manager of the palliative care unit remarked, “The complementary therapy team works alongside the care team, not in a silo. They treat the whole person, not the disease, and involve families and friends. This has been an exceptional program.”

Other comments from staff related to the program adding a more holistic dimension through responding to patients as individuals and enhancing quality of life and comfort. Staff also commented that patients liked the ointments, creams, and taste of the mouth care solution.

Results showed a difference between what patients found problematic and why staff referred them for complementary therapy. While 65% of patients found anxiety and low mood/depression an issue, staff did not refer for these concerns. This finding resulted in the CTC assessing all patients unless there was a reason why she should not approach particular individuals. One reason was as simple as the patient's or family's request to be left alone.

Discussion

As for any new program, there were challenges to work through, but the process was beneficial. The addition of complementary therapists had a positive impact on patients/families and the interdisciplinary team. Patients received more holistic, personalized, high-quality end-of-life care that enhanced not only physical but emotional and spiritual care. Patients reported a decrease in pain, discomfort, restlessness, tension, anxiety, and feelings of depression while they acknowledged an increase in inner stillness/peace. The routine use of aromatherapy products is a further testament to the benefits gained. The narrative comments provided by patients/families and staff revealed how important both the personalized care and the aromatherapy products were to the patient's comfort.

The above results are supported by a study10 that analyzed unsolicited letters of gratitude received by two palliative care teams. According to the study, relatives appeared grateful for the holistic care and special atmosphere created in which their loved ones received professional treatment, emotional support, and were cared for with a humane attitude.

Two other Ontario hospitals are known to provide Therapeutic Touch™. The MRHH program has taken complementary therapy in palliative care to another level by developing a holistic and integrated model providing three complementary modalities: massage/aromatherapy, Reiki, and Therapeutic Touch™.

Conclusion

The integrated complementary therapy pilot program was regarded by patients/families as an essential adjunct to end-of-life care. Massage/aromatherapy, Reiki, and Therapeutic Touch™ provided in a holistic approach proved to enhance the management of end-of-life symptoms. The results of the evaluation were significant and, together with the positive feedback from patients/families and staff, highlight the value of the program. Discussions are underway for permanent funding. The MRHH palliative care team is committed to exploring new measures that have the potential to improve patient care and to better satisfy patients' and families' needs during the last few months of life.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exit.

References

- 1.Canadian Reiki Association. Burlington, Ontario: [Jun 20;2013 ]. What is the Usui System of Natural Healing? [Google Scholar]

- 2.Therapeutic Touch™ Network of Ontario. Etobicoke, Ontario: [Jun 20;2013 ]. What is Therapeutic Touch™? [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell A. Cormack M. The Therapeutic Relationship in Complementary Health Care. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Juhan D. Job's Body: A Handbook for Bodywork. New York: Station Hill Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marianne Tavares: “An Exploratory Study on the Use of Massage and Counselling Skills, Specifically Visualisation, in Chronic Illness”. MSc diss. Brunel University; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Puchalski C. Ferrell B. Virani R. Otis-Green S. Baird P. Bull J. Chochinov H. Handzo G. Nelson-Becker H. Prince-Paul M. Pugliese K. Sulmasy D. Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: The report of the Consensus Conference. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:885–904. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) Guidance on Cancer Services: Improving Supportive and Palliative Care for Adults with Cancer: The Manual. London: NICE; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tavares M. Integrating Clinical Aromatherapy in Specialist Palliative Care. Toronto: Marianne Tavares; 2011. [Jun 20;2013 ]. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts D. Caress A-L. Todd C. Long A. Mackereth P. Carter A. Parkin S. Stringer J. McNulty A. Delgado C. Wilson C. O'Rourke J. A Multi-Centre Evaluation of Complementary Therapy Provision for Patients with Cancer: Access, Expectations, Indications for Therapy. Manchester, UK: St. Ann's Hospice and University of Manchester; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centeno C. Arantzamendi M. Rodriguez B. Tavares M. Letters from relatives: A source of information providing rich insight into the experience of the family in palliative care. J Palliat Care. 2010;26(3):167–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]