Abstract

Faced with a moral dilemma, conflict arises between a cognitive controlled response aimed at maximizing welfare, i.e. the utilitarian judgment, and an emotional aversion to harm, i.e. the deontological judgment. In the present study, we investigated moral judgment in adult individuals with high functioning autism/Asperger syndrome (HFA/AS), a clinical population characterized by impairments in prosocial emotions and social cognition. In Experiment 1, we compared the response patterns of HFA/AS participants and neurotypical controls to moral dilemmas with low and high emotional saliency. We found that HFA/AS participants more frequently delivered the utilitarian judgment. Their perception of appropriateness of moral transgression was similar to that of controls, but HFA/AS participants reported decreased levels of emotional reaction to the dilemma. In Experiment 2, we explored the way in which demographic, clinical and social cognition variables including emotional and cognitive aspects of empathy and theory of mind influenced moral judgment. We found that utilitarian HFA/AS participants showed a decreased ability to infer other people’s thoughts and to understand their intentions, as measured both by performance on neuropsychological tests and through dispositional measures. We conclude that greater prevalence of utilitarianism in HFA/AS is associated with difficulties in specific aspects of social cognition.

Keywords: utilitarianism, moral judgment, social cognition, emotion, Asperger syndrome

INTRODUCTION

Autism is considered an umbrella term for a heterogeneous spectrum of pervasive neurodevelopmental disorders with prominent difficulties in socialization (DSM-IV-TR, 2000). Individuals with high functioning forms of autism (HFA) or Asperger syndrome (AS) typically exhibit a stereotyped behavioral profile characterized by marked impairments in the use of non-verbal communicative cues leading to poor social interactions, as well as repetitive behaviors and restricted interests, motor clumsiness and linguistic oddities such as unusual word choices and inappropriate prosody. Difficulties among individuals with HFA/AS have been linked to impairments in central components of social cognition, including theory of mind (ToM) and empathy (e.g. Baron-Cohen et al., 1985, 1997, 1999; Baron-Cohen and Wheelwright, 2004).

The term ‘empathy’ has been applied to a broad spectrum of different phenomena that emerge in response to the feelings and thoughts of others (Batson, 2009). The most simple of these processes is motor empathy, in which one’s body merely mimics the posture of an observed agent (Hatfield et al., 2009). In everyday life, however, being empathic toward others involves a more complex set of processes. On the one hand, we must have cognitive empathy, or the ability to represent the internal mental state of others in order to infer their feelings, thoughts, intentions and beliefs (Blair and Blair, 2009). These processes have also been referred to as perspective taking, theory of mind (Baron-Cohen, 2005) or empathic inference (Ickes, 2009). Another important group of processes, collectively known as emotional empathy, involve the set of feelings elicited in response to the affective state of others, which can carry feelings of warmth or concern for an agent (empathic concern) or a set of self-oriented feelings generated by such agent (personal distress). Emotional empathy feeds on a phylogenetically earlier neural system of social attachment and reward, supported by circuits within the brain stem, midbrain and ventral tegmental area (Panksepp, 1998; Moll et al., 2007) as well as a broad network of structures that include the amygdala, the pars opercularis and other extended areas within the inferior frontal gyrus, the inferior parietal lobule, as well as the insula (Blair, 2008; Singer et al., 2009; Decety and Michalska, 2010; Hurlemann et al., 2010; Shamay-Tsoory, 2009, 2011). Cognitive empathy relies in a widespread cortical circuit involving the temporoparietal junction (Young et al., 2007, 2010, 2010b), several regions within the prefrontal cortex including the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and Brodmann areas 11 and 10, the medial temporal lobe and parts of the insula (Blair, 2008; Shamay-Tsoory, 2009, 2011). Accordingly, emotional empathy precedes cognitive empathy throughout human ontogeny (de Waal, 2008; Decety and Svetlova, 2012), as observed in children, who are able to emotionally respond to others yet fail at distinguishing between their own and the agent’s distress until later in life (Preston and de Waal, 2002; Singer, 2006). Cognitive and affective aspects of ToM can even be uncoupled by experimentally disrupting the aforementioned neural circuits (Kessler et al., 2009), and can be dissociated when brain networks are clinically altered (Shamay-Tsoory, 2009), as is the case with certain neurological and psychiatric patient populations (Shamay-Tsoory et al., 2005, 2007; Shamay-Tsoory and Aharon-Peretz, 2007).

Among infant (Yirmiya et al., 1992; Blair, 1999), adolescent (Shamay-Tsoory et al., 2002) and adult (Rogers et al., 2007; Dziobek et al., 2008) populations with HFA/AS, emotional empathy has been reported to be relatively spared and major difficulties seem to arise in theory of mind and the cognitive aspects of empathy. Besides the apparently unaffected emotional aspects of empathy per se, emotional disturbances in individuals with HFA/AS have been acknowledged to persist even throughout adulthood (Gray et al., 2012). Such disturbances include impairments in emotion recognition and atypical emotional responses to a wide variety stimuli, including faces (Uono et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2011), body movements (Atkinson, 2009), vocalizations (Heaton et al., 2012) and verbal information (Kuchinke et al., 2011).

Emotion, empathy and ToM have all been strongly related to another complex aspect of social functioning: moral judgment. For years, however, traditional rationalist approaches to moral psychology had emphasized the role of reasoning in the moral judgment both of mature adults (Kohlberg, 1981) and children (Piaget, 1965). Modern trends, instead, have focused on the way affective and intuitive processes influence human morality (Haidt, 2001, 2003). According to Haidt (2003), morally good behavior is promoted by prosocial emotions such as empathy, sympathy and compassion for others. An interesting question thus arises: how is moral judgment affected in a population characterized by a preponderant impairment in cognitive empathy/ToM and atypical emotional processing?

The first studies in the moral cognition of people with autism revealed that the ability of children with autism to distinguish between conventional transgressions (e.g. playing with food, drinking soup out of a bowl at an elegant dinner party, etc.) and moral transgressions (e.g. pulling someone’s hair, kicking someone, etc.) was independent of their performance in simple ToM tasks (Blair, 1996; Leslie et al., 2006). When providing a justification to their judgment of moral transgressions, however, children with autism were usually less able to deliver appropriate or relevant arguments (Grant et al., 2005). Yet, difficulties in justifying judgments delivered to moral dilemmas have also been reported among neurotypical populations (Hauser et al., 2007), stressing the likely role of intuitive processes in driving our moral judgments (Haidt, 2001). As proposed by Cushman et al. (2006), some moral principles may indeed be available consciously while others may simply come intuitively. In this sense, one possibility is that the language and executive functioning characteristic of individuals with autism impairments may further limit their ability to access and/or deliver and share consciously available moral principles.

Among persons with HFA/AS, while compensatory mechanisms may be acquired throughout development (e.g. Frith et al., 1991; Baron-Cohen et al., 1997; Frith, 2004; Moran et al., 2011), impaired ToM and cognitive empathy, as well as disturbances in emotional processing persist onto adulthood (Grey et al., 2012). It is thus sensible to investigate moral judgment in adult populations with autism. To the best of our knowledge, only two other studies have examined moral cognition in this population. Moran et al. (2011) found that HFA/AS participants perceived accidental harms caused by innocent intentions (e.g. accidentally killing someone) as less morally permissible than neurotypical adults. In other words, faced with a negative outcome, they failed to infer the original intention of the agent. Zalla et al. (2011) demonstrated that adults with HFA/AS were incapable of distinguishing moral from disgust (e.g. poking one’s nose in public) transgressions in terms of how serious each transgression was, and this inability was associated with impairment in ToM tasks.

Converging evidence regarding the contribution of emotions has come from several sources (Young and Koenigs, 2007). For instance, neuroimaging studies have consistently demonstrated activation of emotion-related areas when faced with a moral judgment task (Greene et al., 2001, 2004; Moll et al., 2002; Heekeren et al., 2003; Luo et al., 2006; Young et al., 2007; Young and Saxe, 2008). So much so, that moral judgment seems to be malleable—for example, eliciting more severe moral judgments—when the affective state is experimentally manipulated (Wheatley and Haidt, 2005; Valdesolo and DeSteno, 2006; Greene et al., 2008).

A dual process theory of moral judgment has been proposed in order to integrate the contributions of reason and emotion to these complex behaviors (Greene et al., 2001, 2004; Greene, 2003; Greenwald et al., 2003). According to this model, automatic emotional intuitions co-occur with reasoned, deliberative processes to enable moral behavior. Faced with particular moral scenarios, however, conflict emerges between these two systems (Greene et al., 2001, 2004). For these scenarios, while the automatic emotional responses tend to favor deontological judgments (i.e. those associated with a sense of duty and righteousness), controlled cognitive processes promote utilitarian or consequentialist judgments (i.e. those that lead to the greater good). Dilemmas which merely demand the deflection of an existing threat (e.g. hitting a switch to kill one instead of many) are associated with greater activation of brain areas linked to reasoning and problem solving, such as the dorsolateral prefrontal and inferior parietal cortices (Greene et al., 2001, 2004). Faced with these ‘impersonal’, low emotionally charged dilemmas, respondents tend to more frequently deliver utilitarian judgments. Instead, moral scenarios that feature an agent causing severe direct physical harm to a particular target (e.g. pushing a man to his death to save many) yield greater activation in brain areas that have been implicated in emotion and social cognition, including the medial prefrontal cortex and posterior cingulate gyrus (Greene et al., 2001, 2004). In these so-called ‘personal’ moral scenarios, the high emotional saliency results in deontological responses being more frequently delivered than utilitarian ones. This is in contrast with a different type of moral dilemma considered ‘impersonal’, which merely demands the deflection of an existing threat. Faced with these ‘personal’, high emotionally charged dilemmas, respondents tend to more frequently deliver deontological judgments.

Research conducted in clinical populations typically characterized by emotional and social cognition disturbances—such as patients with lesions to the prefrontal cortex, behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia, and psychopaths—has revealed increased rates of utilitarian judgment to moral dilemmas (Eslinger et al., 1992; Blair, 1995; Anderson et al., 2002, 2006; Mendez et al., 2005; Mendez, 2006; Koenigs et al., 2007; Gleichgerrcht et al., 2010; Miller et al., 2010; Young et al., 2010a).

Based on these findings and given the emotion processing and social cognition deficits typical of individuals with HFA/AS, we hypothesized that adult participants in this clinical population would also show increased utilitarian judgment relative to neurotypical controls. Moreover, considering the apparently more severe impairments in cognitive relative to emotional empathy in this population, we hypothesized that utilitarian moral judgment in HFA/AS adults would be associated particularly with impairments in cognitive aspects of empathy.

METHOD

The study was initially approved by the local ethics committee following the standards established by the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

Participants

Thirty-six adults [66.7% (n = 24) male; mean age = 32.6 (s.d. = 10.9); mean years of education = 14.7 (s.d. = 4.0)] with a clinical diagnosis of HFA/AS according to DSM-IV criteria (2000) were recruited from the Institute of Cognitive Neurology (INECO, Argentina) as part of a broader study on cognition in HFA/AS. Diagnosis was based on thorough clinical evaluation of participants and information gathered from their parents. Diagnostic features were further confirmed using screening questionnaires, including the Childhood Asperger Syndrome Test (CAST; Scott et al., 2002) and the Autism Spectrum Quotient for adults (AQ; Baron-Cohen et al., 2001b).

Participants had full-scale IQ scores (Wechsler, 1997) >90, with mean verbal IQ scores of 114 (s.d. = 23.5) and mean performance IQ scores of 104 (s.d. = 15.5)]. Mean CAST was 17.9 (s.d. = 5.6) and mean AQ score was 33.2 (s.d. = 7.5). On an average, participants exhibited mean scores of 73.9 (s.d. = 24.5) on the Systematizing Quotient—Revised (SQ; Wheelwright et al., 2006) and mean scores of 19.2 (s.d. = 12.0) on the Empathy Quotient (EQ; Baron-Cohen and Wheelwright, 2004). All participants gave their informed consent prior to inclusion in this study.

Thirty-six neurotypical (NT) participants [63.8% (n = 23) male; mean age = 34.2 (s.d. = 8.7); mean years of education = 15.1 (s.d. = 4.2); mean verbal IQ = 110.3 (s.d. = 14.3) and mean performance IQ = 109.2 (s.d. = 12.3)] were recruited from the same demographic background as HFA/AS participants. NT participants had neither a personal nor a family history of psychiatric or neurological disease, and were comparable to HFA/AS participants in terms of age (t70 = 0.69, P = 0.49), gender (χ2 = 0.18, P = 0.89, df = 1), education (t70 = 0.41, P = 0.68), verbal IQ (t70 = 0.81, P = 0.42) and performance IQ (t70 = 0.1.18, P = 0.24).

EXPERIMENT 1

Procedure

HFA/AS participants and NT controls were presented with two moral scenarios, in counterbalanced order: the standard trolley dilemma and the footbridge dilemma (Thomson and Parent, 1986; Greene et al., 2001, 2004). Both scenarios required participants to choose whether to harm one person to save five people but differed in the emotional saliency of the harmful act they featured (Section 1 in Supplementary Data), thus constituting one impersonal and one personal moral scenario, as follows:

Impersonal scenario: The trolley dilemma required participants to decide whether to flip a switch to redirect a trolley onto a man, and away from a group of five people (utilitarian response) or whether to allow the trolley to hit the five people (deontological response).

Personal scenario: The footbridge dilemma required participants to decide whether to push a man off a bridge so that his body would stop the trolley from hitting five people further down the tracks (utilitarian response) or whether to allow the trolley to allow the trolley to hit the five people (deontological response).

A third vignette was also presented, which consisted of a non-moral dilemma which lacked emotional saliency (Greene et al., 2004), asking participants to decide whether they would take the train instead of the bus to avoid arriving late to an important meeting. In this sense, the non-moral scenario judged a morally inconsequential dilemma (Section 1in Supplementary Data,).

Participants answered three questions to each scenario:

Would you flip the switch (moral impersonal scenario)/push the man (moral personal scenario)/take the train (non-moral scenario)? (Yes/No). This question provided a direct reflection of the participant’s moral judgment to low and high emotionally salient scenarios. As explained in the introduction, we predicted increased utilitarian judgment among HFA/As participants.

How appropriate is it to flip the switch (moral impersonal scenario)/push the man (moral personal scenario)/take the train (non-moral scenario)? [on a scale of 1 (‘not appropriate at all’) to 10 (‘very appropriate’)]. This question provided a measure of whether participants’ moral judgment was related to tell morally appropriate and inappropriate actions apart. That is to say, if HFA/AS participants delivered utilitarian judgments more frequently, was it because they perceived moral transgressions as more appropriate than neurotypical controls did? Based on previous work showing that HFA/AS participants ignore the intention and focus on the outcome of morally charged actions (Moran et al., 2011), we expected reported appropriateness to be comparable to that of controls.

How strongly do you feel about this decision? [on a scale of 1 (‘no emotional reaction’) to 10 (‘max emotional reaction’)]. This question provided a measure of participant’s own perception of reactivity towards their moral judgment. For a person to express high emotional reactivity to killing one in order to save many, they must understand that the action being executed is a moral transgression and that the victim of said transgression has thoughts and intentions that may differ from our own. Based on previous work showing impairments among HFA/AS participants in identifying moral transgressions (Zalla et al., 2011) and showing impairments in cognitive aspects of ToM (Frith et al., 1991; Baron-Cohen et al., 1997; Frith, 2004), we hypothesized altered levels of emotional reacitivty to moral scenarios.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables (e.g. Yes/No answers) were compared between groups using independent χ2 tests. Ordinal variables were analyzed using independent- and paired-samples t tests for inter- and intra-group comparisons, respectively. The α value for all statistical tests was set at 0.05, two-tailed.

RESULTS

Moral judgment

Non-moral scenario

A total of 35 HFA/AS participants (97.2%) and 36 NT controls (100%) stated that they would take the train instead of the bus to avoid being late for the meeting.

Moral scenarios

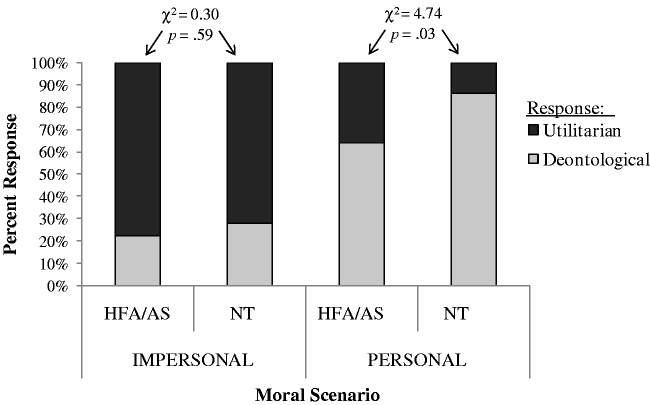

No significant differences were found on the proportion of HFA/AS participants (n = 8, 22.2%) and NT controls (n = 10, 27.7%) who delivered the deontological response (i.e. ‘no, I would not flip the swith’) on the impersonal scenario (χ2 = 0.30, P = 0.59, df = 1) (Figure 1). On the personal scenario, however, a significant difference was found between the groups (χ2 = 4.74, P = 0.03, df = 1), with 31 NT controls (86.1%) but only 23 HFA/AS participants (63.9%) delivering the deontological judgment (i.e. ‘no, I would not push the man off the footbridge’).

Fig. 1.

Proportion of utilitarian and deontological responses to the impersonal and personal scenarios by High Function Autism/Asperger Syndrome participants (HFA/AS) and neurotypical controls (NT).

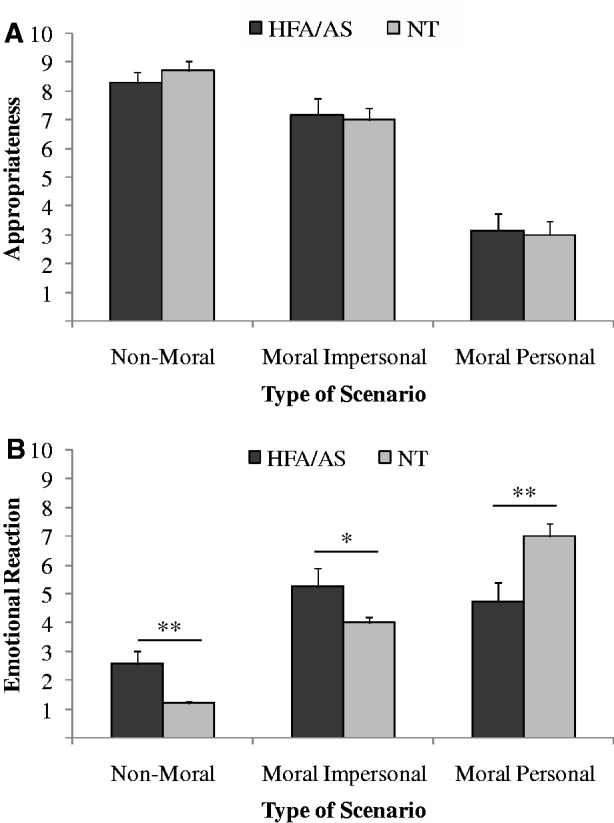

Appropriateness

As shown in Figure 2A, no significant differences were found between the groups on how appropriate they felt the utilitarian decision was on the non-moral scenario (t70 = 0.81, P = 0.50), the impersonal moral scenario (t70 = 0.26, P = 0.69) or the personal moral scenario (t70 = 0.21, P = 0.73). Within the HFA/AS group, the decision take the train instead of the bus on the non-moral dilemma was perceived as significantly more appropriate than the utilitarian judgment on both the impersonal (t34 = 2.0, P = 0.05) and personal (t34 = 8.07, P < 0.001) moral scenarios. The utilitarian judgment on the impersonal moral scenario was also perceived as more significantly appropriate than the utilitarian response to the personal moral dilemma (t34 = 6.44, P < 0.001). The same pattern was observed in NT controls (all P < 0.01).

Fig. 2.

Perceived levels of appropriateness (A) and emotional reactivity (B) reported by High Function Autism/Asperger Syndrome participants (HFA/AS) and neurotypical controls (NT). Error bars are s.e.m. *p < 0.01; **p < 0.001.

Emotional reaction

As shown in Figure 2B, HFA/AS participants responded more strongly than NT controls on the non-moral scenario (t70 = 2.96, P < 0.01) and the impersonal moral dilemma (t70 = 1.93, P = 0.05). On the contrary, the emotional reaction reported by HFA/AS to the personal moral dilemma was significantly lower than that of NT controls (t70 = 2.9, P < 0.01). Participants with HFA/AS reacted significantly more strongly on impersonal (t34 = 4.29, P < 0.001) and personal (t34 = 3.08, P < 0.01) moral scenarios relative to the non-moral dilemma, yet no significant difference was found on the emotional reaction between the two moral dilemmas (t34 = 1.47, P = 0.15). NT controls, instead, showed a marked significantly stronger reaction to the personal dilemma relative to the impersonal one (t34 = 7.52, P < 0.001).

Correlation analyses

In order to test whether IQ was related to moral judgment among HFA/AS participants, we sought correlations between IQ scores and reported levels of appropriateness and emotional reaction. No significant correlations were found between verbal IQ scores and appropriateness on either the impersonal (r = 0.06, P = 0.78) or the personal scenario (r = 0.24, P = 0.21). Similarly, no significant correlations were found between performance IQ scores and appropriateness on neither the impersonal (r = 0.07, P = 0.72) nor the personal scenario (r = −0.04, P = 0.84). Emotional reactivity was also unrelated to either verbal (impersonal: r = −0.04, P = 0.85; personal: r = 0.01, P = 0.99) or performance (impersonal: r = 0.05, P = 0.79; personal: r = 0.07, P = 0.72) IQ.

EXPERIMENT 2

Procedure

In order to further explore moral judgment in HFA/AS, participants from Experiment 1 were further assessed with the following tests:

Theory of mind

Reading the Mind in the Eyes test (MIE; Baron-Cohen et al., 2001a). On this task, participants were presented with photographs of the ocular region of human faces and asked to choose which adjective, among four, best described what the individuals in the picture were feeling. Because participants had to infer what others were feeling, this task measured affective ToM. The score for this task was percent correct. Data for the MIE test was available for 30 HFA/AS participants.

Faux Pas test (Stone et al., 1998). Participants were read 20 short vignettes, 10 of which contained a social faux pas. Each vignette was also placed in front of the participant so they could refer back to the story as needed, thus decreasing working memory load. Following each vignette, participants were asked whether something inappropriate had been said by any of the characters, and if so, asked to give an explanation as to why it was inappropriate. If a faux pas was correctly identified, two follow-up questions were further asked: ‘Why did the person say that?’ and ‘How did the other person feel?’ A memory question is used as a control to confirm that the core events in the stories were retained. Performance on this task was scored regarding the number of (i) ‘hits’, or the correct identification of stories featuring a faux pas (out of 10 points); (ii) ‘rejects’, or the appropriate rejection of those stories which did not contain a faux pas (out of 10 points); (iii) ‘total score’, which resulted from adding hits and rejects; (iv) ‘intentionality’, or the recognition that the person committing the faux pas was unaware that he/she had said something inappropriate (out of 10 points) and (v) ‘emotional attribution’, or the recognition that the person hearing the faux pas felt hurt or insulted (out of 10 points). Therefore, intentionality is a measure of cognitive ToM, while emotional attribution taps on affective ToM. Data for the Faux Pas test was available for 30 HFA/AS participants.

Empathy

HFA/AS participants then responded to the items of three empathy domains, as measured by the Interpersonal Reactivity Inventory (IRI; Davis, 1983):

Perspective taking (PT): the tendency to adopt the point of view of other people;

Empathic concern (EC): the tendency to experience other-oriented feelings of warmth, compassion and concern for those in pain or distress;

Personal distress (PD): the set of self-oriented feelings of unease and discomfort in reaction to the emotions of others.

While PT represents a measure of cognitive empathy and is strongly associated with ToM, EC and PD both belong to the realm of emotional empathy. Data for the IRI was available for 33 HFA/AS participants.

Moral knowledge

Participants were administered the Moral Behavior Inventory (MBI; Mendez et al., 2005), which presents 24 everyday situations (e.g. ‘Fail to keep minor promises’ and ‘Temporarily park in a handicap spot’) to be labeled as ‘not wrong’, ‘mildly wrong’, ‘moderately wrong’ or ‘severely wrong’, on a 4-point Likert scale. The MBI is thought to provide a measure of ‘moral gnosia’ in that it measures patients’ ability to distinguish right from wrong. Data for the MBI was available for 34 HFA/AS participants.

Statistical analysis

Demographic (age and education) and clinical (AQ, CAST, EQ and SQ) variables, as well as performance on ToM tasks and measures of empathy and moral knowledge were initially compared between utilitarian and deontological responders on each moral scenario using independent sample t tests. HFA/AS participants were then classified into the following groups based on their response patterns to both moral scenarios: (i) Extreme Deontologists (ED) not only deliver the deontological response to the personal dilemma (i.e. ‘no, I would not push the man’) but also to the impersonal dilemma (i.e. ‘no, I would not flip the switch’); (ii) Extreme Utilitarians (EU) not only deliver the utilitarian response to the impersonal dilemma (i.e. ‘yes, I would flip the switch’) but also to the personal dilemma (i.e. ‘yes, I would push the man’) and (iii) Majority Responders (MR) deliver the utilitarian judgment in response to the impersonal dilemma and the deontological judgment in response to the personal scenario, a pattern of moral responses that is observed in the majority of participants across studies, on independent pairs of moral dilemmas and in different demographic populations (e.g. Greene et al., 2001, 2004, 2008; Greene, 2003; Mendez et al., 2005; Cushman et al., 2006; Valdesolo and DeSteno, 2006; Hauser et al., 2007). The fourth possibility, i.e. a deontological response to the impersonal scenario and a utilitarian response to the personal scenario was not observed in this sample. Comparisons between ED, EU and ER participants were conducted by means of one-way ANOVAs with Tukey post hoc tests when appropriate. Categorical variables (e.g. gender) were analyzed with contingency tables.

RESULTS

Impersonal scenario

We compared deontological (i.e. ‘no, I would not flip the switch’) and utilitarian (i.e. ‘yes, I would flip the switch’) HFA/AS responders on this low emotionally salient dilemma on several variables in order to determine whether moral judgment was associated with potentially different demographic backgrounds. No significant differences were found in regards to age (t34 = 0.64, P = 0.53), gender (χ2 = 1.87, P = 0.26, df = 1) and years of education (t34 = 0.09, P = 0.93). We also compared clinical variables related to the autistic spectrum in seeking for potential clinical markers that could influence moral cognition among HFA/AS participants. We found that although AQ (t34 = 0.53, P = 0.59), CAST (t34 = 1.19, P = 0.24) and SQ (t34 = 0.97, P = 0.34) scores were comparable between the groups, deontological responders trended toward scoring significantly higher than utilitarians on the EQ (t34 = 1.94, P = 0.06). In comparing performance on affective ToM, as measured by the MIE (t28 = 1.21, P = 0.24), as well as all subscores of the Faux Pas (hits: t34 = 0.57, P = 0.57; rejects: t34 = 0.65, P = 0.52; total: t34 = 0.77, P = 0.45; intentionality: t34 = 0.94, P = 0.35; emotional attribution: t34 = 0.37, P = 0.72) we observed comparable scores between the groups. Neither empathy (perspective taking: t31 = 0.07, P = 0.95; empathic concern: t31 = 0.47, P = 0.65; personal distress: t31 = 1.75, P = 0.09) nor moral knowledge (t32 = 1.61, P = 0.14) differed between deontological and utilitarian responders either (Table 1), stressing that utilitarian vs deontological responses to the impersonal scenario were unrelated to participant’s empathic abilities or capacity to tell good from bad apart.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical profile, theory of mind performance and scores on empathy and moral knowledge measures for High Function Autism/Asperger Syndrome participants who delivered the deontological and utilitarian responses to the impersonal and personal scenarios

| Impersonal scenario |

Personal scenario |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deontological response (n = 8) | Utilitarian response (n = 28) | Deontological response (n = 23) | Utilitarian response (n = 13) | |

| Age (years) | 31.0 (5.4) | 33.7 (11.5) | 33.3 (12.1) | 30.0 (9.0) |

| Gender (% male) | 50 | 71 | 74 | 54 |

| Education (years) | 14.8 (2.5) | 14.6 (4.2) | 14.8 (4.1) | 13.1 (3.2) |

| AQ | 31.9 (10) | 33.6 (6.9) | 34.2 (7.6) | 31.3 (7.3) |

| CAST | 15.7 (4.6) | 18.6 (5.8) | 18.0 (9.4) | 23.3 (15.6) |

| EQ | 26.7 (15.6) | 17.2 (10.2) | 23.3 (15.6) | 17.2 (9.4) |

| SQ | 71.7 (24.4) | 81.9 (25) | 69.1 (25) | 76.2 (24.5) |

| MIE (% total) | 84.7 (10.6) | 78.8 (12) | 82.3 (10.5) | 76.5 (12.9) |

| Faux Pas | ||||

| Hits | 6.9 (1.2) | 6.4 (2.4) | 6.8 (2.1) | 6.1 (2.5) |

| Rejects | 9.5 (0.7) | 9.3 (0.8) | 9.7 (0.5) | 8.7 (1.2)** |

| Total score | 16.5 (1.7) | 15.8 (2.5) | 16.5 (2.3) | 14.8 (2.5)* |

| Intentionality | 5.5 (1.2) | 4.8 (2.1) | 5.6 (1.8) | 4.1 (2.1)* |

| Emotional attribution | 4.7 (1.9) | 4.4 (1.9) | 4.5 (1.9) | 4.4 (2.1) |

| IRI | ||||

| Perspective taking | 14.6 (6.6) | 14.4 (6.6) | 17.2 (7.2) | 12.1 (5.1)* |

| Empathic concern | 23.0 (6.1) | 24.4 (7.4) | 24.7 (7.7) | 23.0 (6.1) |

| Personal distress | 16.3 (4.9) | 20.3 (5.4) | 20.2 (5.1) | 17.8 (6.1) |

| Moral knowledge (total) | 57.4 (13) | 65.9 (9.7) | 62.4 (11) | 67.4 (9.9) |

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

AQ = Autism Quotient; CAST = Childhood Asperger Syndrome Test; EQ = Empathy Quotient; SQ = Systematizing Quotient—Revised; MIE = Reading the Mind in the Eyes test; IRI = Interpersonal Reactivity Index.

Personal scenario

We again sought for potential demographic and clinical differences that may explain utilitarian vs deontological responses to the personal moral dilemma. No significant differences were found between deontological (i.e. ‘no, I would not push the man’) and utilitarian (i.e. ‘yes, I would push the man’) HFA/AS responders in regards to age (t34 = 0.41, P = 0.41), gender (χ2 = 1.51, P = 0.22, df = 1) and years of education (t34 = 1.24, P = 0.22). Scores obtained on the AQ (t34 = 1.05, P = 0.30), CAST (t34 = 0.02, P = 0.98), EQ (t34 = 1.18, P = 0.26) and SQ (t34 = 0.78, P = 0.44) were comparable between the groups. No significant differences were found for performance on affective ToM, as measured by the MIE (t28 = 1.26, P = 0.22). The capacity to detect an actually occurring faux pas (hits: t34 = 0.83, P = 0.41) did not differ significantly between the groups, but utilitarian responders performed significantly worse than deontological responders in recognizing that no faux pas was present (rejects: t34 = 3.52, P < 0.01) and on the task overall (total: t34 = 2.07, P < 0.05). The ability to infer other people’s intentionality on the Faux Pas test was also significantly poorer among utilitarian HFA/AS responders (t34 = 2.26, P = 0.03), despite no significant differences on the Emotional Attribution score (t28 = 0.05, P = 0.88). While empathic concern (t31 = 0.64, P = 0.53) and personal distress (t31 = 1.12, P = 0.28) were comparable between the groups, a significant difference was found for perspective taking (t31 = 2.09, P = 0.04), with utilitarian responders reporting lower tendencies to adopt the point of view of other people relative to deontological responders. Moral knowledge (t32 = 1.32, P = 0.20) did not differ the groups (Table 1).

Moral judgment patterns

Based on the criteria outlined above, 8 participants were classified as ED, 13 participants as EU and 16 parcitipants as MR. Said classification was not predicted by age (F2,34 = 2.35, P = 0.11), gender (χ2 = 2.75, P = 0.25, df = 2), or years of education (F2,34 = 2.2, P = 0.13). Nor were the groups significantly different on the AQ (F2,34 = 0.82, P = 0.45), CAST (F2,34 = 0.03, P = 0.97), EQ (F2,34 = 1.1, P = 0.34), or SQ (F2,34 = 2.25, P = 0.12). The groups were comparable on their ToM performance, both on the MIE (F2,28 = 1.78, P = 0.19) and the different subscores of the Faux Pas (hits: F2,28 = 1.07, P = 0.35; rejects: F2,28 = 2.3, P = 0.11; intentionality: F2,28 = 0.84, P = 0.44; and emotional attribution: F2,28 = 0.19, P = 0.83). When considering the overall performance on the task, however, a significant difference was found between the groups (F2,28 = 3.4, P < 0.05), with EU scoring significantly lower than both ED (P < 0.05) and MR (P < 0.05). ED and MR, instead, had similar scores on the total Faux Pas (P = 0.82). A similar pattern was observed for empathy measures: while the groups did not differ significantly on empathic concern (F2,30 = 0.68, P = 0.51) and personal distress (F2,30 = 1.46, P = 0.25), EU participants scored significantly lower on the Perspective Taking scale (F2,30 = 3.49, P = 0.04) than ED (P < 0.05) and MR (P < 0.05) participants, but the latter groups did not differ between each other (P = 0.78). These results were found in the absence of significant differences on moral knowledge (F2,31 = 1.43, P = 0.25) across the groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical profile, theory of mind performance and scores on empathy and moral knowledge measures for High Function Autism/Asperger Syndrome participants who were classified as either extreme deontologists (ED), extreme utilitarians (EU) and majority responders (MR) based on their answers to both impersonal and personal scenarios (see text for further clarification)

| Extreme deontologists | Extreme utilitarians | Majority responders | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 30.0 (7.0) | 30.0 (9.0) | 34.9 (12.6) |

| Gender (% male) | |||

| Education (years) | 15.5 (2.1) | 13.1 (3.2) | 15.8 (4.4) |

| AQ | 35.5 (9.8) | 31.3 (7.3) | 33.9 (7.3) |

| CAST | 17.3 (4.3) | 17.9 (5.6) | 17.9 (6.5) |

| EQ | 20.0 (10) | 23.3 (15.6) | 16.6 (9.5) |

| SQ | 91.5 (26.3) | 69.1(24.5) | 72.8 (23.5) |

| MIE (% total) | 88.2 (12.1) | 76.5 (13) | 80.5 (11.6) |

| Faux Pas | |||

| Hits | 7.5 (1.0) | 6.1 (2.5) | 6.7 (2.2) |

| Rejects | 9.7 (0.2) | 9.2 (1.0) | 9.5 (0.5) |

| Total Score | 17.4 (1.2) | 14.8 (2.2) | 16.9 (2.7)* |

| Intentionality | 6.0 (0.9) | 4.8 (2.1) | 5.1 (1.9) |

| Emotional attribution | 4.0 (2.0) | 4.4 (2.1) | 4.6 (1.9) |

| IRI | |||

| Perspective taking | 17.3 (4.2) | 11.0 (4.2) | 15.4 (6.1)* |

| Empathic concern | 23.0 (5.8) | 21.5 (2.3) | 25.4 (8.4) |

| Personal distress | 17.3 (4.5) | 17.8 (6.1) | 20.9 (5.1) |

| Moral knowledge (total) | 57.3 (17) | 67.4 (9.9) | 63.5 (9.7) |

*p < 0.05.

AQ = Autism Quotient; CAST = Childhood Asperger Syndrome Test; EQ = Empathy Quotient; SQ = Systematizing Quotient—Revised; MIE = Reading the Mind in the Eyes test; IRI = Interpersonal Reactivity Index.

Correlation analyses

Correlations were sought between variables that significantly differed between the groups in order to better understand whether they were tapping on the exact same constructs, or whether they could be providing information of related yet distinguishable constructs. No correlations were found within HFA/AS participants between Perspective Taking and the total score on the Faux Pas (r = 0.08, P = 0.68) nor any of its subscores (hits: r = 0.16, P = 0.45; rejects: r = 0.27, P = 0.20; intentionality: r = 0.12, P = 0.58; emotional attribution: r = 0.23, P = 0.28). The same held true when correlations were sought independently within deontological and utilitarian responders to the impersonal and personal scenario separately, and within EU, ED and MR participants independently (all P > 0.14).

DISCUSSION

Moral cognition constitutes a core feature of our social interactions in real life. In the present study, we investigated moral judgment among adult individuals with HFA/AS. As predicted based on this population’s well-established cognitive ToM impairments (e.g. Baron-Cohen et al., 1985, 1997, 1999; Stone et al., 1998; Baron-Cohen and Wheelwright, 2004; Moran et al., 2011; Zalla et al., 2011), we found increased utilitarian judgment to personal moral dilemmas relative to neurotypical controls. In other words, when faced with emotionally high saliency scenarios that involve a moral transgression resulting from direct physical harm to an agent, persons with HFA/AS more frequently than controls favored the utilitarian outcome. This phenomenon, however, was not observed with regards to impersonal dilemmas: when emotional saliency was low, HFA/AS and NT controls were as likely to deliver utilitarian judgments. Also importantly, these findings were unrelated to participants’ verbal or performance IQ scores.

Remarkably, increased utilitarianism among HFA/AS participants was not associated with their perception of appropriateness to inflict harm onto an agent to maximize the benefit for others. HFA/AS individuals and controls both considered that pushing a man onto the train tracks to save five lives (personal scenario) was less appropriate than flipping a switch to kill a man instead of five (impersonal scenario). Both groups also judged appropriateness at a similar level on each scenario, yet HFA/AS participants still delivered the utilitarian judgment more frequently on the personal dilemma. In fact, we further found that utilitarian and deontological HFA/AS respondents exhibited similar scores on a dispositional measure of moral knowledge, suggesting that their perception of what is right and wrong does not influence moral judgment. This dissociation between moral knowledge and moral judgment is consistent with reports of patients with behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia, who exhibit increased utilitarianism associated with brain degeneration of social cognition and emotional circuits (Mendez et al., 2005; Gleichgerrcht et al., 2010).

We thus sought to understand what aspects of emotion and social cognition, particularly ToM, could be associated with increased utilitarian judgment in this clinical group. It became evident from patients’ reports of emotional reactivity to each scenario that emotion deficits were relevant to moral judgment. HFA/AS participants reported significantly higher emotional reactions than neurotypical controls not only to the moral impersonal dilemma, but even to a non-moral dilemma that featured no transgressions, harm or victims. Yet, when faced with a situation charged with high emotional saliency, their emotional reaction was significantly decreased relatively to controls. Unlike the latter group who exhibit increased reactivity to personal dilemmas relative to impersonal ones, HFA/AS participants reported similar levels of emotional reactivity to both types of scenarios. This finding is consistent with previous reports highlighting, on the one hand, that individuals with HFA/AS exhibit atypical emotional processing (e.g. Gray et al., 2011), and on the other, an extensive overlap between HFA/AS and alexithymia, the inability to identify or describe emotions (Tani et al., 2004; Fitzgerald and Bellgrove, 2006). In fact, alexithymia has been found to be a better predictor than autism symptom severity of decreased brain activation in areas related to prosocial emotions (Bird et al., 2010) and reduced eye fixation when individuals with autism look at social scenes (Bird et al., 2011). Our present findings in this context call for further research exploring the relationship between measures of alexithymia and moral cognition in HFA/AS populations.

Our hypothesis that utilitarian moral judgment was associated with impairments in cognitive aspects of social cognition was also confirmed in this study. In particular, for situations posing low emotional saliency (i.e. impersonal dilemmas), moral judgment was not associated either with demographic, clinical or social cognition parameters. When faced with a dilemma bearing high emotional saliency, however, utilitarian judgment was linked to a decreased ability to deny that a faux pas had been commited (Faux Pas’ reject score) and to pick up on social appropriateness (Faux Pas’ total score), as well as a decreased ability to understand others’ intentions (Faux Pas’ intentionality subscore), and a diminished tendency to take other’s point of view (perspective taking subscale of the IRI). Participants who delivered the utilitarian response to the personal moral scenario had poorer performance and lower self-reported scores on all four variables, relative to deontological responders with the same diagnosis. Previous studies in adult HFA/AS populations reported severe impairments particularly in these aspects of theory of mind and empathy (Rogers et al., 2007; Dziobek et al., 2008). Moreover, our results are consistent with Moran et al.’s (2011) findings showing that HFA/AS participants fail to judge the moral inappropriateness of an action based on the original intentions of the agent. Instead, they do so by focusing on the outcome of said action. This is likely because, as revealed in the present study, their ability to infer the intentions of other’s and adopt other’s point of view are impaired.

What our findings suggest is that among adults with HFA/AS, those who showed more severe impairments in cognitive ToM and empathy were more likely to deliver utilitarian judgments. These data further support previous findings showing increased utilitarianism in different patient populations with cognitive empathy impairments (Eslinger et al., 1992; Blair, 1995; Anderson et al., 2002, 2006; Mendez et al., 2005; Mendez, 2006; Koenigs et al., 2007; Gleichgerrcht et al., 2010; Miller et al., 2010; Young et al., 2010a). For this reason, it also became relevant to investigate empathy and ToM among extreme utilitarian and deontological individuals. Participants who delivered extreme utilitarian judgment (that is, utilitarian responses not only to the impersonal dilemma as do most respondents but to the personal dilemma as well), showed diminished scores particularly on cognitive ToM/empathy. Moreover, it seem as though participants with extreme utilitarian judgment deviate from the rest of the HFA/AS individuals: their cognitive ToM was significantly lower than that of extreme deontologists (those who deliver deontological judgments to both types of scenario) and the majority of participants (those who exhibit utilitarian responses to the impersonal scenarios but deontological judgment on the personal dilemma), while these two latter groups did not differ between each other.

There are certain limitations to the present study that must be taken into consideration for future work in this field. First, it is important for subsequent studies to replicate these findings using other independent moral scenarios in order to determine the generalizability of the patterns found here. Greene et al. (2001, 2004) and other authors have collected dozens of moral dilemmas that are similar in structure to the trolley and footbridge pair of dilemmas. As well, small variations in the scenarios can test for other subtle yet important aspects of moral judgment. For instance, there are dilemmas in which one person is killed to save many, including the person who commits the moral transgression (as opposed to the scenarios used in the present study, in which the person killing one to save many would not die if s/he decided to not kill the victim). Other dilemmas test a choice to commit a moral transgression for one’s own selfish benefit (rather than for the greater good). Second, more complex predictive models and statistical approaches that control for the effects of multiple comparisons will contribute to identifying the reliability of the present findings. Third, all moral cognition variables analyzed in this study resulted from structured yes/no or Likert-scale answers. Asking participants to verbalize the justifications that underlie their moral judgment can provide very useful information to better comprehend the moral psychology of individuals with HFA/AS.

Understanding the complex interaction between higher cognitive functions in autism carries important implications. First, it provides additional support to theoretical models highlighting the role of emotion in moral judgment. Among HFA/AS adults, disruption of prosocial sentiments leads to increased utilitarianism, which, as argued above, is relevant in the understanding of empathizing vs systemizing trends among persons with autism. From a clinical perspective, our findings provide useful information in the design of intervention programs aimed at training social skills among individuals with autism. These programs usually use hypothetical situations to help individuals recognize emotions, intentions and beliefs of others in order to foster and promote more fruitful social interactions (Carter et al., 2004; Golan and Baron-Cohen, 2006). Accordingly, our study reveals that the use of moral scenarios with high emotional saliency can be useful stimuli to incorporate in attempting to work on the cognitive aspects of empathy/ToM.

Taken together, the findings from the present study reveal that impairments in cognitive aspects of empathy and theory of mind typical of individuals with HFA/AS can elicit utilitarian judgment. Greater prevalence of consequentialism when adults with HFA/AS are faced with high emotionally charged moral dilemmas appears to be associated with difficulties in social cognition.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at SCAN online.

FUNDING

Fundación INECO grant.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank participants and their families for their willingness to participate in the present study.

REFERENCES

- Anderson SW, Barrash J, Bechara A, Tranel D. Impairments of emotion and real-world complex behavior following childhood- or adult-onset damage to ventromedial prefrontal cortex. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2006;12(2):224–35. doi: 10.1017/S1355617706060346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson SW, Bechara A, Damasio H, Tranel D, Damasio AR. Impairment of social and moral behavior related to early damage in human prefrontal cortex. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2(11):1032–37. doi: 10.1038/14833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association, A.P. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th edn. 2000. DSM-IV-TR, 4th edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson AP. Impaired recognition of emotions from body movements is associated with elevated motion coherence thresholds in autism spectrum disorders. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47(13):3023–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S. Mindblindness: An Essay on Autism and Theory of Mind. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S, Jolliffe T, Mortimore C, Robertson M. Another advanced test of theory of mind: evidence from very high functioning adults with autism or asperger syndrome. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1997;38(7):813–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S, Leslie AM, Frith U. Does the autistic child have a “theory of mind”? Cognition. 1985;21(1):37–46. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(85)90022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S, O’Riordan M, Stone V, Jones R, Plaisted K. Recognition of faux pas by normally developing children and children with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1999;29(5):407–18. doi: 10.1023/a:1023035012436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S. The empathy quotient: an investigation of adults with Asperger syndrome or high functioning autism, and normal sex differences. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2004;34(2):163–75. doi: 10.1023/b:jadd.0000022607.19833.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Hill J, Raste Y, Plumb I. The “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” Test revised version: a study with normal adults, and adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2001a;42(2):241–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Skinner R, Martin J, Clubley E. The autism-spectrum quotient (AQ): evidence from Asperger syndrome/high-functioning autism, males and females, scientists and mathematicians. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2001b;31(1):5–17. doi: 10.1023/a:1005653411471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batson DC. These things called empathy: eight related but distinct phenomena. In: Decety J, Ickes WJ, editors. The Social Neuroscience of Empathy. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bird G, Press C, Richardson DC. The role of alexithymia in reduced eye-fixation in autism spectrum conditions. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2011;41(11):1556–64. doi: 10.1007/s10803-011-1183-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird G, Silani G, Brindley R, White S, Frith U, Singer T. Empathic brain responses in insula are modulated by levels of alexithymia but not autism. Brain. 2010;133(Pt 5):1515–25. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair RJ. A cognitive developmental approach to mortality: investigating the psychopath. Cognition. 1995;57(1):1–29. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(95)00676-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair RJ. Brief report: morality in the autistic child. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1996;26(5):571–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02172277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair RJ. Psychophysiological responsiveness to the distress ofothers in children with autism. Personality and Individual Differences. 1999;26(3):477–85. [Google Scholar]

- Blair RJ. Fine cuts of empathy and the amygdala: dissociable deficits in psychopathy and autism. Q J Exp Psychol (Hove) 2008;61(1):157–70. doi: 10.1080/17470210701508855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair RJ, Blair KS. Empathy, Morality, and Social Convention: Evidence from the Study of Psychopathy and Other Psychiatric Disorders. Cambridge: MIT Press; 2009. pp. 139–52. [Google Scholar]

- Carter C, Meckes L, Pritchard L, Swensen S, Wittman PP, Velde B. The Friendship Club: an after-school program for children with Asperger syndrome. Family and Community Health. 2004;27(2):143–50. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200404000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushman F, Young L, Hauser M. The role of conscious reasoning and intuition in moral judgment: testing three principles of harm. Psychological Science. 2006;17(12):1082–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MH. Measuring individual differences in empathy: evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1983;44(1):113–26. [Google Scholar]

- de Waal FB. Putting the altruism back into altruism: the evolution of empathy. Annual Review of Psychology. 2008;59:279–300. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decety J, Michalska KJ. Neurodevelopmental changes in the circuits underlying empathy and sympathy from childhood to adulthood. Dev Sci. 2010;13(6):886–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decety J, Svetlova M. Putting together phylogenetic and ontogenetic perspectives on empathy. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience. 2012;2(1):1–24. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dziobek I, Rogers K, Fleck S, et al. Dissociation of cognitive and emotional empathy in adults with Asperger syndrome using the Multifaceted Empathy Test (MET) Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2008;38(3):464–73. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0486-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eslinger PJ, Grattan LM, Damasio H, Damasio AR. Developmental consequences of childhood frontal lobe damage. Archives of Neurology. 1992;49(7):764–9. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1992.00530310112021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald M, Bellgrove MA. The overlap between alexithymia and Asperger’s syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2006;36(4):573–6. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0096-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith U. Emanuel Miller lecture: confusions and controversies about Asperger syndrome. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45(4):672–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith U, Morton J, Leslie AM. The cognitive basis of a biological disorder: autism. Trends in Neuroscience. 1991;14(10):433–8. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(91)90041-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleichgerrcht E, Torralva T, Roca M, Pose M, Manes F. The role of social cognition in moral judgment in frontotemporal dementia. Social Neuroscience. 2010;6(2):113–22. doi: 10.1080/17470919.2010.506751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golan O, Baron-Cohen S. Systemizing empathy: teaching adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism to recognize complex emotions using interactive multimedia. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18(2):591–617. doi: 10.1017/S0954579406060305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant CM, Boucher J, Riggs KJ, Grayson A. Moral understanding in children with autism. Autism. 2005;9(3):317–31. doi: 10.1177/1362361305055418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray K, Jenkins AC, Heberlein AS, Wegner DM. Distortions of mind perception in psychopathology. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108(2):477–79. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015493108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray K, Keating C, Taffe J, Bereton A, Einfeld S, Tonge B. Trajectory of behavior and emotional problems in autism. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2012;117(2):121–33. doi: 10.1352/1944-7588-117-2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene J. From neural ‘is’ to moral ‘ought’: what are the moral implications of neuroscientific moral psychology? Nature Review Neuroscience. 2003;4(10):846–9. doi: 10.1038/nrn1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene J, Morelli SA, Lowenberg K, Nystrom LE, Cohen JD. Cognitive load selectively interferes with utilitarian moral judgment. Cognition. 2008;107(3):1144–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene J, Nystrom LE, Engell AD, Darley JM, Cohen JD. The neural bases of cognitive conflict and control in moral judgment. Neuron. 2004;44(2):389–400. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene J, Sommerville RB, Nystrom LE, Darley JM, Cohen JD. An fMRI investigation of emotional engagement in moral judgment. Science. 2001;293(5537):2105. doi: 10.1126/science.1062872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald AG, Nosek BA, Banaji MR. Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: I. An improved scoring algorithm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85(2):197–216. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidt J. The emotional dog and its rational tail: a social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychological Review. 2001;108(4):814–34. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.4.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidt J. The moral emotions. In: Davidson RJ, Scherer KR, Goldsmith HH, editors. Handbook of Affective Sciences. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield E, Rapson RL, Yen-Chi L. Emotional contagion and empathy. In: Decety J, Ickes WJ, editors. The Social Neuroscience of Empathy. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser M, Cushman F, Young L, Jin R, Mikhail J. A dissociation between moral judgments and justifications. Mind and Language. 2007;22(1):1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Heaton P, Reichenbacher L, Sauter D, Allen R, Scott S, Hill E. Measuring the effects of alexithymia on perception of emotional vocalizations in autistic spectrum disorder and typical development. Psychological Medicine. 2012;4:1–7. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712000621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heekeren HR, Wartenburger I, Schmidt H, Schwintowski HP, Villringer A. An fMRI study of simple ethical decision-making. NeuroReport. 2003;14(9):1215–9. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200307010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlemann R, Patin A, Onur OA, Cohen MX, Baumgartner T, Metzler S, et al. Oxytocin enhances amygdala-dependent, socially reinforced learning and emotional empathy in humans. J Neurosci. 2010;30(14):4999–5007. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5538-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ickes WJ. Empathic accuracy: its links to clinical, cognitive, developmental, social, and physiological psychology. In: Decety J, Ickes WJ, editors. The Social Neuroscience of Empathy. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler J, Kalbe E, Schlegel M, et al. Dissociating cognitive from affective theory of mind: a TMS study. Cortex. 2009;46(6):769–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenigs M, Young L, Adolphs R, et al. Damage to the prefrontal cortex increases utilitarian moral judgements. Nature. 2007;446(7138):908–11. doi: 10.1038/nature05631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlberg L. The Philosophy of Moral Development 1. New York: Harper & Row; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Kuchinke L, Schneider D, Kotz SA, Jacobs AM. Spontaneous but not explicit processing of positive sentences impaired in Asperger’s syndrome: pupillometric evidence. Neuropsychologia. 2011;49(3):331–338. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie AM, Mallon R, DiCorcia JA. Transgressors, victims, and cry babies: is basic moral judgment spared in autism? Social Neuroscience. 2006;1(3–4):270–83. doi: 10.1080/17470910600992197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Q, Nakic M, Wheatley T, Richell R, Martin A, Blair RJ. The neural basis of implicit moral attitude–an IAT study using event-related fMRI. NeuroImage. 2006;30(4):1449–57. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez MF. What frontotemporal dementia reveals about the neurobiological basis of morality. Medical Hypotheses. 2006;67(2):411–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2006.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez MF, Anderson E, Shapira JS. An investigation of moral judgement in frontotemporal dementia. Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology: Official Journal of the Society for Behavioral and Cognitive Neurology. 2005;18(4):193–7. doi: 10.1097/01.wnn.0000191292.17964.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MB, Sinnott-Armstrong W, Young L, et al. Abnormal moral reasoning in complete and partial callosotomy patients. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48(7):2215–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll J, de Oliveira-Souza R, Bramati IE, Grafman J. Functional networks in emotional moral and nonmoral social judgments. NeuroImage. 2002;16(3 Pt 1):696–703. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moll J, de Oliveira-Souza R, Garrido GJ, et al. The self as a moral agent: linking the neural bases of social agency and moral sensitivity. Social Neuroscience. 2007;2(3–4):336–52. doi: 10.1080/17470910701392024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran JM, Young L, Saxe R, et al. Impaired theory of mind for moral judgment in high-functioning autism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011;108:2688–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011734108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panksepp J. Affective Neuroscience. New York: Oxford University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Piaget J. The Moral Judgment of the Child. New York: Free Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Preston SD, de Waal FB. Empathy: its ultimate and proximate bases. The Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2002;25(1):1–20; discussion 20–71. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x02000018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers K, Dziobek I, Hassenstab J, Wolf OT, Convit A. Who cares? Revisiting empathy in Asperger syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2007;37(4):709–15. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0197-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott FJ, Baron-Cohen S, Bolton P, Brayne C. The CAST (Childhood Asperger Syndrome Test): preliminary development of a UK screen for mainstream primary-school-age children. Autism. 2002;6(1):9–31. doi: 10.1177/1362361302006001003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamay-Tsoory SG. Cambridge: The Social Neuroscience of Empathy; 2009. Empathic processing: its cognitive and affective dimensions and neuroanatomical basis; pp. 215–32. [Google Scholar]

- Shamay-Tsoory SG. The neural bases for empathy. Neuroscientist. 2011;17(1):18–24. doi: 10.1177/1073858410379268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamay-Tsoory SG, Aharon-Peretz J. Dissociable prefrontal networks for cognitive and affective theory of mind: a lesion study. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45(13):3054–67. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamay-Tsoory SG, Shur S, Barcai-Goodman L, Medlovich S, Harari H, Levkovitz Y. Dissociation of cognitive from affective components of theory of mind in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research. 2007;149(1–3):11–23. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamay-Tsoory SG, Tomer R, Berger BD, Goldsher D, Aharon-Peretz J. Impaired “affective theory of mind” is associated with right ventromedial prefrontal damage. Cognitive and Behavioral Neurology: Official Journal of the Society for Behavioral and Cognitive Neurology. 2005;18(1):55–67. doi: 10.1097/01.wnn.0000152228.90129.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamay-Tsoory SG, Tomer R, Yaniv S, Aharon-Peretz J. Empathy deficits in Asperger syndrome: a cognitive profile. Neurocase. 2002;8(3):245–52. doi: 10.1093/neucas/8.3.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer T. The neuronal basis and ontogeny of empathy and mind reading: review of literature and implications for future research. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2006;30(6):855–63. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone VE, Baron-Cohen S, Knight RT. Frontal lobe contributions to theory of mind. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 1998;10(5):640–56. doi: 10.1162/089892998562942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tani P, Lindberg N, Joukamaa M, et al. Asperger syndrome, alexithymia and perception of sleep. Neuropsychobiology. 2004;49(2):64–70. doi: 10.1159/000076412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson JJ, Parent W. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1986. Rights, restitution, and risk: essays, in moral theory. [Google Scholar]

- Uono S, Sato W, Toichi M. The specific impairment of fearful expression recognition and its atypical development in pervasive developmental disorder. Social Neuroscience. 2011;6(5–6):452–63. doi: 10.1080/17470919.2011.605593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdesolo P, DeSteno D. Manipulations of emotional context shape moral judgment. Psychological Science. 2006;17(6):476–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale®. 3rd edn. San Antonio: Pearson; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wheatley T, Haidt J. Hypnotic disgust makes moral judgments more severe. Psychological Science. 2005;16(10):780–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheelwright S, Baron-Cohen S, Goldenfeld N, et al. Predicting Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ) from the Systemizing Quotient-Revised (SQ-R) and Empathy Quotient (EQ) Brain Research. 2006;1079(1):47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang HH, Savosyanov AN, Tsai AC, Liou M. Face recognition in Asperger syndrome: a study on EEG spectral power changes. Neuroscience Letters. 2011;492(2):84–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yirmiya N, Sigman MD, Kasari C, Mundy P. Empathy and cognition in high-functioning children with autism. Child Development. 1992;63(1):150–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young L, Bechara A, Tranel D, Damasio H, Hauser M, Damasio A. Damage to ventromedial prefrontal cortex impairs judgment of harmful intent. Neuron. 2010a;65(6):845–51. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young L, Camprodon JA, Hauser M, Pascual-Leone A, Saxe R. Disruption of the right temporoparietal junction with transcranial magnetic stimulation reduces the role of beliefs in moral judgments. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010b;107(15):6753–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914826107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young L, Cushman F, Hauser M, Saxe R. The neural basis of the interaction between theory of mind and moral judgment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104(20):8235–40. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701408104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young L, Dodell-Feder D, Saxe R. What gets the attention of the temporo-parietal junction? An fMRI investigation of attention and theory of mind. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48(9):2658–64. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young L, Koenigs M. Investigating emotion in moral cognition: a review of evidence from functional neuroimaging and neuropsychology. British Medical Bulletin. 2007;84:69–79. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldm031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young L, Saxe R. The neural basis of belief encoding and integration in moral judgment. NeuroImage. 2008;40(4):1912–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalla T, Barlassina L, Buon M, Leboyer M. Moral judgment in adults with autism spectrum disorders. Cognition. 2011;121(1):115–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.