Abstract

While it is known that all German anatomical institutes that have been examined made use of the bodies of victims of the National Socialist (NS) regime for teaching and research between 1933 and 1945, detailed investigations on many institutions are still missing. Among these is the anatomical institute of the University of Cologne. This university was the first university to voluntarily self-align with the policies of the new regime and was therefore often called a ‘model NS university’. In addition, Cologne was the site of a NS special court and a central place for executions. Based on archival sources, this study investigates the interaction between the anatomical institute of the University of Cologne with the NS authorities and the origin of the body supply for dissection and research. The documents reveal that the institute continued to receive bodies from traditional sources like the public morgue and hospitals, but with the beginning of World War II (WWII) an increasing amount of bodies of victims of the NS regime became available. Thus, the anatomical institute of Cologne collaborated and benefited from the policies of the NS regime, especially during WWII, like all other already explored anatomical institutes in Germany to varying degrees.

Keywords: anatomy, bodies of the executed, National Socialism, Third Reich

Introduction

In the first decade of the 21st century there has been a lot of basic research on the history of anatomy in the Third Reich. However, while it is known that all German anatomical institutes that have been examined made use of the bodies of victims of the National Socialist (NS) regime for teaching and research, a comprehensive historical investigation as well as detailed studies on many institutions have yet to be pursued. Out of a total of 31 anatomical departments existing in Germany and its occupied territories during the Third Reich, detailed studies are only available for 12 of them (Mörike, 1988; Forsbach, 2006; Hildebrandt, 2009a,b,c; Blessing et al. 2012; Noack, 2012; Oehler-Klein et al. 2012; Redies et al. 2012; Schultka & Viebig, 2012; Ude-Koeller et al. 2012; Schütz et al. 2013). Among the missing institutions is the anatomical institute of the University of Cologne. Cologne is of special interest in this historical period as it was not only the location of one of the NS Sondergerichte (special courts notorious for their harsh legislation and quick trials), but also one of the central places of executions in the Third Reich, the main prison ‘Klingelpütz’. The cooperation of the young anatomical institute with the regime solved a problem that persisted since its foundation: finally the anatomical institute of Cologne acquired enough bodies for anatomical dissections, while the circumstances of this acquisition were (if at all) of secondary importance.

After the closing of the so-called ‘Old University’ in Cologne (1798) by the French following the War of the First Coalition, it was refounded in 1919 as the ‘New University’. With the introduction of a preclinical medical curriculum an anatomical institute was opened in 1925 (Ortmann, 1986). During the period of the Weimar Republic the institute suffered from a chronic lack of bodies as was documented by the body registers. Only the urban district of Cologne was available as an area for body procurement, while bodies from the surrounding Rhine Province were delivered to the anatomical institute of the University of Bonn. The anatomical institute of Cologne obtained its material mostly from marginalized social groups, which included destitute deceased, newborns, suicides, prisoners, drowned persons and unidentifiable bodies. Most of the bodies came from urban hospitals and the public morgue. The process of procurement was based on a rescript of the Prussian Ministry of the Interior from 9 June 1889 that regulated the procurement of bodies for the anatomical institutes (Viebig, 2002). Addressees were the authorities responsible for prisons, poorhouses and workhouses, which were subject to the local governments. It must be pointed out that historically, executed persons were the first legal source for the anatomical institutes (Redies & Hildebrandt, 2012). However, the edict had no holding legal force; it was more of a reminder than strict law and did allow many exceptions. Noteworthy is the option for relatives to disagree with the delivery of the convict to an anatomical institute if they were able to take over the costs for the funeral. The edict aimed to counteract the lack of bodies, which caused disturbances of the anatomical teaching that was viewed as a basis of medical studies and was therefore of great public interest. Ministerial decrees of the years 1926, 1927 and 1933 confirmed the continuing validity of the rescript of 1889.

The situation of the body supply changed with the NS regime and even more so during World War II (WWII). The current study analyzes how the anatomical institute of Cologne benefited from and collaborated with the new government. Specific questions concern the extent of the involvement of the institute with the NS regime, the traditional sources of bodies, and the number and social background of the persons, including NS victims, whose bodies were used for anatomical purposes during that time period. This analysis of archival material and other literature on the subject reveals that the anatomical institute of the University of Cologne was clearly collaborating with and profiting from NS policies, especially during WWII.

Materials and methods

Archival material from the anatomical institute of the University of Cologne

The history of the anatomical institute in Cologne is well documented compared with other facilities and faculties of the university. The largest part of archival material is held at the archives of the university. It includes the body registers from 1925, when the institute was founded, until 1942, when one of the first extensive bombing raids by the allied forces struck Cologne. The registers contain information on the total number of bodies split into the delivering facilities, followed by a personal comment of the current director (from time to time there is additional information about the sex). In addition, the personal correspondences of the directors of the anatomical institute provide important information from 1933 until December 1945 (with gaps between July 1944 and December 1945). These anatomists' personal commitment was often a decisive factor in body procurement. The documents contain the correspondence with the mayor of Cologne – until 1933 this was Konrad Adenauer who later became the first Chancellor of the German Federal Republic – various Reich Ministries, as well as the board of the university (ex officio the mayor was chairman of the board) and colleagues from other German anatomical institutes. All of these files are referred to as UAK Zug./Nr.

Because of the destruction of the building housing the Historisches Archiv der Stadt Köln (city archive) in a cave-in due to underground construction in March 2009, access to files of municipal institutions (1815–1945), for example, hospital and cemetery administration, morgue, registry office and the employment of prisoners of war, is currently impossible.

Material from other archives

The State Archive of North Rhine-Westphalia holds the case files of the regional NS special courts. Of interest are the files regarding the special courts with death sentences and executions in the city prison of Cologne in the Vollstreckungsbezirk VII (execution district VII). They are located at the section Rheinland (Düsseldorf), portfolio NW 0174.

Bodies of the executed that were not claimed by relatives were delivered to the universities of Münster, Bonn or Cologne. In addition to the special court in Cologne, the courts in Essen, Düsseldorf, Duisburg, Aachen, Trier, Koblenz and Hagen provided bodies for the institute.

The German Federal Archive in Berlin holds the personal files of the former directors of the anatomical institute in Cologne, containing their membership in the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (NSDAP; the National Socialist German Workers' Party) and its sub-organizations. The personal file of Hans Böker is located under the signature R 4901/13259 and the personal file of Franz Stadtmüller under R 4901/13277.

Further sources of information

There are two monographs on the history of anatomy in Cologne. The medical doctoral thesis titled Die Geschichte der Anatomie an der Universität Köln von 1478–1798 (The history of anatomy at the University of Cologne 1478–1798; Walter Pribilla, 1940) does not concern the time period investigated here and is of no further interest. Rolf Ortmann, a former director of the anatomical institute, wrote a history of the institute in 1986. He dealt with the jüngere Geschichte des Anatomischen Institut der Universität zu Köln 1919–1984. 65 Jahre in bewegter Zeit (The younger history of the anatomical institute of the University of Cologne 1919–1984. 65 years in turbulent times). Ortmann's work suffers from its anecdotal writing style. The extremely short treatment of the time period of NS is conspicuous – three pages in a 136-page book – as is the dispatch of the NS regime as an ‘interregnum’ (an interim government to fill a political void, which was created by the collapse of the former Weimar government). This display needs to be corrected.

In terms of the general NS history of Cologne the situation of source materials is difficult. Reasons for this are the extensive destructions during the air strikes, the post-war confusion and the destruction of the city archives, all of which constituted an irreparable loss for the tracing of the history of the Rhine metropolis. Studies on the history of the university treat the medical school and the anatomical institute only marginally, mentioning the institute mostly in the context of the severe destruction in WWII and in the chapters on persecution of the university teachers – the chairman of the anatomical institute Otto Veit was retired prematurely because of his so-called ‘Jewish descent’.

Definition of the term ‘NS victim’

By definition, a NS victim is a person who suffered damage through or was killed by the NS regime (Duden online, 2013). The legal definition follows the Bundesentschädigungsgesetz (German Restitution Laws) of the 1950s. The text of the law states that only certain people can be seen as victims of NS: persons who were pursued due to their political opposition against NS or due to ‘racial’, religious or ideological reasons were persecuted by Nazi violent measures and therefore suffered damages to life, body, health, freedom, property, fortunes, in their professional or economical progressing. Abbreviated they are called ‘Verfolgte’ (persecuted persons) (Bundesministerium der Justiz, 2009).

For this study, we know that the following groups of people delivered to the anatomical institute of Cologne were defined as NS victims: (i) prisoners of the Rhenish-Westphalian workhouse Brauweiler; (ii) prisoners of war; (iii) prisoners of concentration camps; and (iv) executed persons. The body registers contain no indication that the anatomical institute of Cologne received bodies of euthanasia victims.

The workhouse Brauweiler was an early concentration camp and later a prison for the Gestapo (Geheime Staatspolizei, Secret State Police) of Cologne (Kahlfeld & Schaffer, 2009). It is known that until 1945, 550 inmates of this camp were involuntarily sterilized at the university medical center of Cologne (Daners, 1996).

The body registers noted that Russian prisoners of war were also dissected at the anatomical institute of the University of Cologne. They probably originated from the transit camp in Cologne.

Inside the metropolitan area, on the site of the Cologne Fair, there was the so-called Messelager Köln. From 1942 till 1944 it was used as a sub-camp of the concentration camp Buchenwald and run by the SS (Schutzstaffel, Protection Squadron). The SS-Baubrigade III (construction brigade) was housed there. The inmates were concentration camp prisoners who were responsible for clean-up, disposal of unexploded ordnance devices and the recovery of bodies after bombings. Furthermore, on the site was a prison of the Gestapo as well as buildings for forced laborers, prisoners of war and transit camps for the Jewish population and the Sinti and Roma (Fings, 2004).

The largest contingent of bodies was that of the bodies of the executed. The expansion of NS legislation requiring the death penalty, especially for political and petty crimes, led to a great increase of executions, especially during the war years. The criminal nature of this new legislation justifies the consideration of all of the executed as NS victims (Hildebrandt, 2012). During the Third Reich the main prison ‘Klingelpütz’ took over the function of a central execution site for the NS justice where 1000–1500 people fell victim to NS prosecution (Klein, 1983; Wüllenweber, 1990).

Results

The University of Cologne in the Third Reich

On 11 April 1933 the University of Cologne was the first to perform the Selbstgleichschaltung (self-alignment) with NS university policies, even before the official law was ratified, and was therefore the first university to fall in line with the new rulers. While the University of Cologne has been called a ‘model NS university’ for this reason, it is possibly more accurate to interpret this as an opportunistic attitude paired with partial agreement as well as tendering to the new rulers (Golczewski, 1988; Heiber, 1992). It is no coincidence that the first president of the university after the NS ascent to power was a member of the NSDAP and of the medical school. Three out of the five university presidents during the Third Reich were physicians, and all five were NSDAP members.

Physicians played a major role in the implementation of the NS ideology, and many seemed to support the party themselves (Lifton, 1986). Therefore, it is not surprising that of all professions the physicians had the largest share of memberships of the NSDAP and/or their associated organizations with over 45, and 20% of these were also members of the SA or the SS (Kater, 1989). This attitude is reflected in numbers from the University of Cologne. Approximately 89% of the teaching staff of the medical school held a membership of the NSDAP, among them 16 of the 18 chairmen. In comparison, this ratio was significantly lower within the remaining university. In all other faculties an average of 43% of the staff and 21 of 49 chairmen were party members (Franken, 2008). Party membership was widespread as it was supposed to promote one's career. These data have to be treated with caution as they refer to 1944, and it is likely that party membership was not that high in the earlier years of the regime. The aforementioned problem with sources makes it virtually impossible to establish the membership rates for earlier years. However, an investigation among the physicians in private practice painted a similar picture: three-quarters of the Rhine physicians were institutionally embedded in the NS system, and in the district of Cologne 58% of the physicians were members of the NSDAP (Rüther, 2001). These numbers show that despite the fact that the Rhine region was very catholic and formerly strongly dominated by the German Centre Party, there were few oppositionists and most of the population favored the regime (Klein, 1983; Dietmar, 1992; Heidenreich, 2004).

Twenty percent of the professors at the University of Cologne were dismissed for so-called racial or political reasons, a number that reflected the national average; two professors were killed by the NS regime because of their political convictions (Meuthen, 1998; Serup-Bildfeldt, 2004; Grüttner, 2008).

The recruitment practice at the anatomical institute was influenced by NS politics. Otto Veit (1884–1976), director of the institute since its foundation in 1925, was forced into early retirement in 1937, as he was considered to be of mixed race according to the Nuremberg ‘racial’ laws and had to vacate his position following the Deutsches Beamtengesetz (German Law of Civil Servants, January 1937) (Golczewski, 1988; Liebermann, 1988; UAK 192/181). In 1938, Hans Böker (1886–1939) took his place. He was a member of the SA and of the Opferring (lit. circle of victims) der NSDAP (the Opferring was not an official party institution, but was tolerated by the party because its purpose was to raise funds for the NSDAP). According to Hossfeld, Böker was also a supporting member of the SS and member of the NSDAP, the Reichsluftschutzbund (Air Protection Corps), Nationalsozialistische Volkswohlfahrt (National Socialist People's Welfare) and Reichsbund der Kinderreichen (Reich's League of those wealthy in children) (Hossfeld, 2006). Böker expressed a race theory that opposed certain aspects of the social Darwinism of the NS ideologists, proposing that indirect environmental effects on an organism cause ‘reconstructions’, wherein the subject actively adapts to the changing conditions (Meyer-Abich, 1941; Mertens, 1955). Possibly the numerous memberships in NS organizations were supposed to serve as a protection against repercussions following his ideological dissent for the Reich Ministry of Science, Education and Culture (REM) had already been made aware of him (Hossfeld, 2006). After Böker's death in 1939, Franz Stadtmüller (1889–unknown) became his successor and held the position as director until 1945. He was a supporting member of the SS and member of the NSDAP.

The anatomical institute of Cologne in the Third Reich: new sources for body procurement

During the Weimar Republic there were several institutions that regularly provided bodies for the anatomical institute of Cologne. These were city hospitals, whereby the Cologne university medical center Lindenburg delivered by far the largest contingent, and the public morgue. The city's facilities for the disabled, welfare centers and religious hospitals played only a marginal role in the supply.

The sources of body procurement for the anatomical institute changed during the Third Reich. Certain religious hospitals were no longer included because of low delivery numbers. The same applied for police authorities and welfare offices. Other areas of change involved the following.

Barracks that had been formerly used by the British occupying forces following World War I were transformed into a retirement home and asylum called Riehler Heimstätten. Founded in 1926, it included 2200 beds and held about 80% of Cologne's spots for the elderly (Dietmar, 1992). These Heimstätten were the source for the fourth highest number of bodies made available by municipal facilities, but from mid-1941 they were claimed as and converted to an increasing extent into an auxiliary hospital for the able-bodied and thus ‘more valuable’ population. A shifting system was devised that relocated the residents of the Heimstätten to the killing center in Hadamar. Those people became victims of the Decentralised Euthanasia in summer 1942. Of the patients transferred from Cologne to Hadamar hardly anyone would have survived (Süss, 2003; Rüther, 2005). However, it must be assumed that those bodies the registers allocated to the Heimstätten were not euthanasia victims, but in earlier years residents of the retirement home and as from 1941 patients of the auxiliary hospital. No bodies came in with the designation ‘Hadamar’.

Between 1938 and 1941 the establishment of 11 so-called auxiliary hospitals increased the much-needed number of hospital beds in Cologne (Wenge, 2006). Although this provisionary arrangement was not able to compensate for the serious shortage of doctors, it was nevertheless a relief for the local health system. Four of those auxiliary hospitals (the nursing home Vingst and Dellbrück – wards for terminally sick patients with tuberculosis – as well as the Kolpinghaus and a hospital at Schulstraße, for which there is no further information available) delivered bodies of the deceased to the anatomical institute of Cologne from 1941 onwards.

The state prison ‘Klingelpütz’ started to supply the anatomical institute in 1935 with several bodies per year. This state prison ‘Klingelpütz’ is to be differentiated here from ‘Klingelpütz’ as the execution site of the special courts. The latter was specifically assigned to the special courts and was thus a source for bodies of the executed, while the state prison mostly delivered bodies of prisoners who had died under ‘natural’ circumstances within the prison. These included death due to bad hygienic conditions, malnutrition or torture. In 1933, the prison was temporarily used as a preventive detention facility and, since November 1944, it was presumably used by the Gestapo (Roth, 2005; Thiesen, 2011).

In 1940 registry offices of the urban districts supplied only few bodies for anatomical research and dissection.

Judging by the body registers and the occasional information from notes in the correspondence of the directors, the anatomical institute used the bodies primarily for dissection by medical students. This contributes to a good education of the future physicians, which represents a major interest of the university and the public. Since 1939 – the first year the institute gained bodies from the execution site – all those bodies were ‘used for scientific purposes’ (i.e. UAK 9/683, translation by the author). There are no other comments on this matter whatsoever.

The delivery of bodies from those sources, which are – in light of the history of body sources of other anatomical institutes – to be designated as ‘traditional’, remained the same throughout the transition from the Weimar Republic to the NS period. However, among the new sources were four groups of institutions that provided bodies that must be defined as NS victims. All of them became victims of NS crimes during WWII.

Since 1939 the bodies of detainees of the Rhenish-Westphalian workhouse Brauweiler were brought as dissection material to the anatomical institute of Cologne. This is important to note, as Brauweiler is situated in the Rhine Region, which was normally the exclusive procurement area of the anatomy of Bonn.

In 1941 the anatomical institute received seven bodies of Russian prisoners of war. So far it has not been possible to identify the victims or find out with certainty from which facilities they originated. However, it is likely that they were imprisoned in the Messelager Köln, as this was a transit camp for prisoners of war amongst others for those of Soviet nationality (Fings, 1996).

In the following year, 1942, two bodies were delivered from the concentration sub-camp Messelager Köln. As the names of these persons are missing in the body register, an identification has not yet been possible.

The most significant new source of bodies was the execution site with its regular delivery of bodies of the executed, which became available from 1939 onwards. While the execution rates had been low during the Weimar Republic, the numbers of executions rose dramatically during WWII.

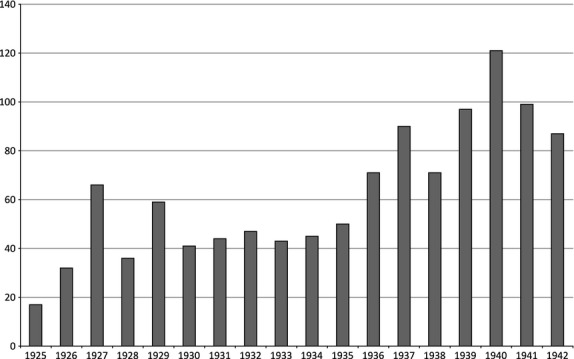

Figure 1 gives an overview on the development of the delivery of bodies to the anatomical institute of the University of Cologne from 1925 to 1942. Since the late 1930s – especially with the beginning of WWII due to the addition of NS victims – an increase in body numbers per year becomes apparent.

Fig. 1.

The number of bodies for anatomical teaching and research during the Weimar Republic and the Third Reich at the anatomical institute of the University of Cologne.

The development of professional interactions between the facilities providing the bodies and the anatomical institute as well as the establishment of the institute itself was crucial for the increasing numbers of bodies available to the anatomical institute of Cologne. In a letter from Director Veit to the board of the university regarding the supply with bodies, Veit mentioned that a higher delivery rate was possible by improving relationships with delivery facilities. For example, the body count of the small hospital Deutz, where a former assistant of the anatomical institute started to work, had increased in 1 year from nothing to seven (UKA 9/238,1).

In 1940, the highest number of bodies in the young history of the anatomical institute of Cologne was reached with a total of 121. Director Stadtmüller mentioned in his annual report that this amount of bodies ‘truly satisfied’ the requirement for the teaching of a then very high number of students, and it proved that it was possible to receive an adequate supply from the municipality (UKA 9/683). This was the first time ever that a director expressed his satisfaction about this subject, as all previous correspondence contained only complaints about the serious shortage of bodies for anatomical education. It is important to remember that the municipality was the only official regional procurement area that did not expand during the reign of the Nazi Party; the only exception being the workhouse Brauweiler, which used to exclusively deliver to the anatomical institute of the University of Bonn. The change was possibly due to the fact that Brauweiler served as a prison for the Gestapo of Cologne.

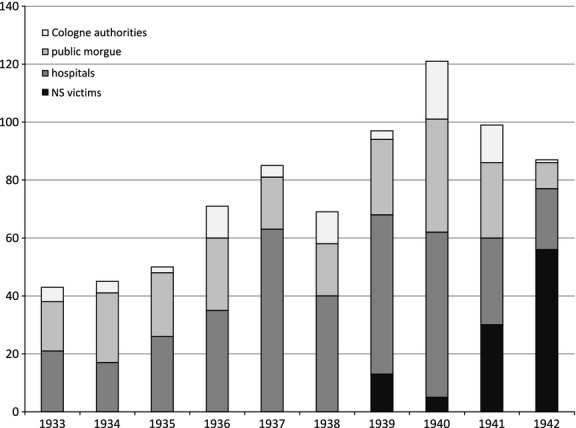

Figure 2 presents the ratio of the different delivery facilities in comparison with the total number of bodies. The majority of bodies through the years of the Third Reich came regularly and in relatively constant numbers from the urban hospitals, followed by the public morgue, while bodies of NS victims were available in increasing numbers from 1939 onwards. During that year the first executed persons were delivered to the anatomical institute of Cologne, but only in 1941 did this group of bodies reached a higher number. In 1941, the institute received a total of 99 bodies, 21 of which came from the execution site. In the following year a majority of 50 of 87 bodies were those of executed persons, while the deliveries from traditional institutions decreased.

Fig. 2.

The total number of bodies of the anatomical institute of the University of Cologne; divided into major categories of the delivery facilities.

The general decline of body deliveries from other sources than the execution site since 1940 can be explained by the severe destructions of urban facilities during the devastating aerial warfare as well as the exhaustion of the storage capacity at the anatomical institute.

It is important to point out that the bodies of the executed were a preferred source of ‘material’ by the anatomists. ‘Material’ from these bodies was considered to be ‘fresh as in life’ and the planning of the research was easier with a known date of execution (Redies & Hildebrandt, 2012). In August 1942, director Stadtmüller wrote to the board of the university that the anatomical institute of Cologne ‘is currently over abundantly supplied with bodies so that it cannot receive any more. Therefore I have already refused to accept the deliveries from the morgue and the registry offices, and in the near future I will not be able to accept bodies of the executed. I intend to give 10 bodies of the executed and 15 other bodies to Würzburg. Heil Hitler!’ (UAK 9/683, translation by the author) The anatomical institute was in such a ‘comfortable’ situation concerning body supply as would have been unthinkable during the time of the Weimar Republic.

In February 1943 the anatomical institute was partially destroyed by incendiary bombs but continued to work under wartime restrictions until at least July 1944, when an increased delivery of the executed was documented (UAK 9/239). In October 1944 the University of Cologne was officially closed. It was not until March 1945 that Cologne was finally liberated by American troops.

Bodies of executed NS victims

In 1939, the Reich Minister of Justice addressed a memorandum to Adolf Hitler in which he noted that the special courts should be equated with courts-martial, but they were never labeled as such (Gruchmann, 1987). Hence, it is not surprising that the vast majority of those executed were sentenced to death for looting very often for seemingly minor crimes, for example a man in 1945 in Cologne who stole a laundry bag, a letter opener and a magnifying glass (NW 174/295, I). Foreign workers were sporadically among the victims as well as less frequently ‘real’ criminals, for example, murderers.

In 1933, a decree by the Prussian Ministry of Science, Art and Culture determined that the bodies of executed persons should be assigned to 12 selected anatomical institutions, including the University of Cologne (6 October 1933) (Viebig, 2002). The relatives of the deceased had the right to ask for the release of the body, if they were able to pay for the funeral. Otherwise, the assigned anatomical institutes were given the opportunity to use the executed for dissection. This arrangement was amended several times, and from November 1942 onwards relatives were no longer informed about the date of execution and were denied the right to claim the body (Waltenbacher, 2008). It is interesting to note that the University of Cologne sent an inquiry to the REM only 11 months after Hitler's Machtergreifung (seizure of power) in January 1933: ‘Perhaps it could be achieved by the Minister of Justice, that all communists who have been executed for political crimes should be delivered without exception to the anatomical institutes. Currently, families are still allowed to claim the bodies of the executed for a funeral.’ (UAK 9/683, translation by the author) This approach shows ruthlessness and a willingness to benefit from the NS system. The university as well as the anatomical institute of Cologne obviously had opportunistically adapted to the political conditions, given the fact that they aimed their rhetoric against the ‘communists’, a particularly persecuted group of political opponents of the NS regime. The inquiry attempted to establish a working routine in favor of the anatomical institute and to the disadvantage of the relatives. Although this request was at first indignantly rejected by the authorities, the prisons and the prosecution supported the anatomists in providing facilities to dissect executed persons directly after the beheading. In Cologne a specially constructed dissection room was attached to the main prison for the use of medical research. The REM intended to enlarge the execution site into a research institution that allowed new areas of scientific investigation for anatomists and physiologists (Waltenbacher, 2008). The NS regime had a particular interest in providing enough bodies for medical education, as a shortage of bodies in the dissection courses could lead to a delay in the licensing of future physicians, who were needed in greater numbers especially during WWII.

During the NS era medical ethics changed its focus away from the concern for the individual patient to that for the health of the whole Volkskörper (body of the people) (Stöckel, 2005; Bruns, 2009). This background may explain the following statement by the Cologne anatomists, when they wrote to the REM that it ‘would quite match the gesundes Volksempfinden (healthy national sensibility) if the body of an executed person serves the interests of the Volksgemeinschaft (people's community), which he offended most severely, even after his death’ (UAK 9/683, translation by the author).

The ‘Klingelpütz’ was the central place of execution for the special courts in Cologne, Aachen, Duisburg, Düsseldorf, Essen, Trier, Koblenz, Luxembourg and (in the early days of the war) Dortmund. In addition, it was the site for executions following military trials in occupied Belgium, France and Holland, sometimes also for executions following death sentences by the Volksgerichtshof (People's Court, the highest special court in the Third Reich with over 5000 enforced death sentences). Finally, it served as an execution site for convicted Nacht und Nebel prisoners (‘night and fog’, a secret decree by Hitler that aimed at preventing crimes against the German authorities in the occupied territories) (Grimm & Lauf, 1994; Daners & Wißkirchen, 2006).

In 1939, when the first bodies of the executed from the ‘Klingelpütz’ were delivered to the anatomical institute, this group made up 9.7% of the absolute numbers of bodies for anatomical dissection in Cologne. In 1941 their share rose to 20.8%, with a peak of 43.5% in 1942, when the body journals suddenly ended. The REM promised the board of the Cologne Medical School in 1939 that it had ‘attempted the most complete procurement of bodies of the executed for the universities of Cologne, Bonn and Münster’ (Waltenbacher, 2008, translation by the author). Based on the special court records at the State Archive of North Rhine-Westphalia, further numbers could be reconstructed for Execution District VII. In 1943 at least 21 and in 1944 another 14 persons were executed following verdicts by the special courts, and were delivered to the anatomical institute of Cologne. Between December 1944 and January 1945 the execution site in the prison of Cologne was damaged in a bombing raid and the guillotine had to be dismantled; thereafter death sentences were executed by shooting (NW 174/295, II). From this time on the numbers of bodies of the executed delivered to the anatomical institute ceased, which may have been due to the physical state of the bodies after shooting or to the collapsing infrastructure at the end of the war that included a lack of fuel and a recruitment of staff and students to the battlefront.

Concluding remarks

Compared with the Weimar Republic, the number of bodies delivered to the anatomical institute of Cologne increased during the Third Reich. The relationship between the city institutions like hospitals or municipal administration and the directors of the anatomical institute – which were maintained through regular correspondence – helped to create stable working routines and establish the anatomical institute within the city. The institute had learned to make better use of its official procurement area – the municipality of Cologne. These facilities became a reliable resource for bodies during the Weimar Republic and the Third Reich. Their deliveries rose steadily and reached their highest point in 1940. The large city hospitals and the public morgue led this list. Later the importance of these ‘traditional’ procurement areas declined, as from 1940 onwards Cologne became increasingly a target of the allied air forces and was completely in ruins by the end of the war. From the start of WWII in 1939 the bodies of NS victims became a growing contingent within the body supply of the anatomical department – foremost among them the bodies of the executed. The last existing body registers from 1942 reveal that by then the numbers of the NS victims had surpassed the numbers of bodies from traditional sources.

In conclusion, the anatomical department in Cologne joins the other already investigated German anatomical institutes in the Third Reich. With a total number of about 810 bodies (body registers 1933–1942 plus executed 1943–1944) during the Third Reich, the anatomical institute of Cologne ranged clearly below the average in terms of the total number of bodies used (Hildebrandt, 2009b; S. Hildebrandt, Personal communication). The anatomical institute of Würzburg, which was one of the largest institutions of its kind in the early 20th century, had a total of 944 corpses whereof the executed accounted for 13% (Blessing et al. 2012). The anatomical institute of Bonn, which was the closest to Cologne, used partially the same procurement area (the workhouse Brauweiler, the central execution site) and had twice as many medical students as Cologne had a total of 1025 bodies at its disposal, thereof 154 executed (15%) (Forsbach, 2006). Among the bodies of the anatomical institute of Cologne were ∼11–14% executed. Compared with Bonn, Cologne as a relatively small department was quite well supplied with bodies. However, these comparisons should be treated with caution, mainly because of the differences in the sufficiency of the source materials.

It holds true that the anatomical institute of the University of Cologne evidently benefited from the new body ‘material’ made available by the criminal NS regime for dissection and research – so did all the other German institutes. The accessible sources do not give any more precise information about the fate of the bodies after the collapse of the Third Reich. There is just a short notification from December 1945 that stated that a large number of bodies of the executed were still in the storage containers of the morgue. Those bodies were to be prepared for the identification department of the United Nations, and apparently two agents of the Luxembourgian record department came looking for the bodies of their nationals who were put to death at the ‘Klingelpütz’ (UAK 9/650). It can be speculated that the bodies of NS victims were retained at least for a while. But it is not known if there was any effort to identify the victims or the ways in which the institute dealt with the bodies afterwards.

The documents reviewed for this investigation showed no evidence of insights into the anatomists' actions, their doubt or remorse; the anatomical institute of Cologne was focused primarily on increasing the number of bodies for medical education and even actively collaborated with the NS authorities. The history of anatomy in the Third Reich serves as a warning that ethics in medicine must not depend on the existing political system (Cohen & Werner, 2009; Hildebrandt, 2009c).

Acknowledgments

The author is especially indebted to Sabine Hildebrandt, MD for the critical reading of the manuscript, as well as for assistance with the translation of the text. Furthermore, the author thanks colleagues Jens Lohmeier for the productive help with the interpretation of the sources and Mathias Schütz for the help with the revision. The reviewers are also thanked for helpful comments on an earlier version of this paper.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Blessing T, Wegener A, Koepsell H, et al. The Würzburg Anatomical Institute and its supply of corpses (1933–1945) Ann Anat. 2012;194:281–285. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruns F. Medizinethik im Nationalsozialismus. Entwicklungen und Protagonisten in Berlin (1939–1945) Stuttgart: Franz Steiner; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bundesministerium der Justiz. 2009. Bundesgesetz zur Entschädigung für Opfer der nationalsozialistischen Verfolgung (Bundesentschädigungsgesetz – BEG). Available from: http://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/bundesrecht/beg/gesamt.pdf (Accessed 14 May 2013)

- Cohen J, Werner RM. On medical research and human dignity. Clin Anat. 2009;22:161–162. doi: 10.1002/ca.20746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daners H. ‘Ab nach Brauweiler!’ Nutzung der Abtei Brauweiler als Arbeitsanstalt, Gestapogefängnis, Landkrankenhaus. Pulheim: Verein für Geschichte und Heimatkunde; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Daners H, Wißkirchen J. Was in Brauweiler geschah. Die NS-Zeit und ihre Folgen in der Rheinischen Provinzial-Arbeitsanstalt. Dokumentation. Pulheim: Verein für Geschichte; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dietmar C. Die Chronik Kölns. Dortmund: Chronik; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Duden online. 2013. NS-Opfer, das. Available from: http://www.duden.de/rechtschreibung/NS_Opfer (Accessed 14 May 2013)

- Fings K. Messelager Köln Ein KZ-Außenlager im Zentrum der Stadt. Köln: Emons; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fings K. Sklaven für die ‘Heimatfront’. Kriegsgesellschaft und Konzentrationslager. In: Echternkamp J, editor. Die deutsche Kriegsgesellschaft 1939 bis 1945. Erster Halbband: Politisierung, Vernichtung, Überleben. München: DVA; 2004. pp. 195–271. [Google Scholar]

- Forsbach R. Die Medizinische Fakultät der Universität Bonn im Dritten Reich. München: R. Oldenbourg; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Franken I. ‘Dass ich kein rabiater Nationalsozialist gewesen bin.’ NS-Medizin an Kölner Unikliniken am Beispiel von Hans C. Naujoks (1892–1959), Direktor der Universitäts-Frauenklinik. In: Der Vorstand der Uniklinik Köln, editor. Festschrift des Universitätsklinikums Köln. 100 Jahre ‘auf der Lindenburg’. Köln: J.P. Bachem; 2008. pp. 99–134. [Google Scholar]

- Golczewski F. Kölner Universitätslehrer und der Nationalsozialismus. Personengeschichtliche Ansätze. Köln: Böhlau; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Grimm H, Lauf E. Die Abgeurteilten des Volksgerichtshofes: Eine Analyse der sozialen Merkmale. Hist Soc Res. 1994;19:33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Gruchmann L. Justiz im Dritten Reich 1933–1940 Anpassung und Unterwerfung in der Ära Gürtner. München: R. Oldenbourg; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Grüttner M. Die Säuberung’ der Universitäten: Entlassungen und Relegationen aus rassistischen und politischen Gründen. In: Scholtyseck J, Studt C, editors. Universitäten und Studenten im Dritten Reich. Bejahung, Anpassung, Widerstand. XIX. Königswinterer Tagung vom 17–19. Februar 2006. Berlin: Lit; 2008. pp. 23–39. [Google Scholar]

- Heiber H. Universität unterm Hakenkreuz. Teil II. Die Kapitulation der Hohen Schulen. Das Jahr 1933 und seine Themen. Band 1. München: Saur; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Heidenreich E. Hier wohnte Köln 1933 bis 1945. In: Serup-Bilfeldt K, editor. Stolpersteine. Vergessene Namen, verwehte Spuren. Wegweiser zu Kölner Schicksalen in der NS-Zeit. Mit einem Beitrag von Elke Heidenreich. 2nd edn. Köln: Kiepenheuer & Witsch; 2004. pp. 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrandt S. Anatomy in the Third Reich: an outline, part 1. National Socialist politics, anatomical institutions, and anatomists. Clin Anat. 2009a;22:883–893. doi: 10.1002/ca.20872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrandt S. Anatomy in the Third Reich: an outline, part 2. Bodies for anatomy and related medical disciplines. Clin Anat. 2009b;22:894–905. doi: 10.1002/ca.20873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrandt S. Anatomy in the Third Reich: an outline, part 3. The science and ethics of anatomy in National Socialist Germany and postwar consequences. Clin Anat. 2009c;22:906–915. doi: 10.1002/ca.20874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrandt S. Anatomy in the Third Reich: careers disrupted by National Socialist policies. Ann Anat. 2012;194:251–266. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossfeld U. 2006. Evolution und Schöpfung. Geschichte und Theorie des Darwinismus/Antidarwinismus – ein Überblick -, Redemanuskript: Erfurter Dialog, Staatskanzlei am 23. Januar 2006. Available from: http://www.thueringen.de/imperia/md/content/tsk/veranstaltungen/erfurterdialog/erfurter_dialog_hossfeld.pdf (Accessed 14 May 2013)

- Kahlfeld R, Schaffer W. LVR. Qualität für Menschen. Bestand ‘Arbeitsanstalt bzw. Rheinisches Landeskrankenhaus Brauweiler 1833–1978’. Köln: Landschaftsverband Rheinland; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kater M. Doctors under Hitler. Chapel Hill, London: The University of North Carolina Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Klein A. Köln im Dritten Reich: Stadtgeschichte der Jahre 1933–1945. Köln: Greven; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Liebermann P. ‘Die Minderwertigen müssen ausgemerzt werden’. Die Medizinische Fakultät 1933–1946. In: Blaschke W, Hensel O, Liebermann P, et al., editors. Nachhilfe zur Erinnerung. 600 Jahre Universität zu Köln. Köln: Pahl-Rugenstein; 1988. pp. 110–120. [Google Scholar]

- Lifton RJ. The Nazi doctors. Medical killing and the psychology of genocide. New York: Basic Books; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Mertens R. Neue Deutsche Biographie 2. 1955. Böker, Hans. (original version). Available from: http://www.deutsche-biographie.de/pnd116223359.html (Accessed 24 January 2013) [Google Scholar]

- Meuthen E. Kleine Kölner Universitätsgeschichte. Köln: Rektor der Univ. zu Köln; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer-Abich A. Konstruktion und Umkonstruktion. Ein Nachruf auf HANS BÖKER ergänzt durch neue Beiträge zur Theorie der Umkonstruktionen und der Frage ihrer Vererbbarkeit. Jena: Gustav Fischer; 1941. [Google Scholar]

- Mörike KD. Geschichte der Tübinger Anatomie. Tübingen: J. C. B. Mohr (Paul Siebeck); 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Noack T. Anatomical departments in Bavaria and the corpses of executed victims of National Socialism. Ann Anat. 2012;194:286–292. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2012.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oehler-Klein S, Preuss D, Roelcke V. The use of executed Nazi victims in anatomy: findings from the Institute of Anatomy at Gießen University, pre- and post-1945. Ann Anat. 2012;194:293–297. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2012.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortmann R. Die jüngere Geschichte des anatomischen Instituts der Universität zu Köln 1919–1984. 65 Jahre in bewegter Zeit. Köln: Böhlau; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Redies C, Hildebrandt S. Anatomie im Nationalsozialismus. Ohne jeglichen Skrupel. Dtsch Ärztebl Int. 2012;109:A2413–A2415. [Google Scholar]

- Redies C, Fröber R, Viebig M, et al. Dead bodies for the anatomical institute in the Third Reich: an investigation at the University of Jena. Ann Anat. 2012;194:298–303. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth T. Köln (‘Klingelpütz’) In: Benz W, Distel B, editors. Der Ort des Terrors. Geschichte der nationalsozialistischen Konzentrationslager. Band 2: Frühe Lager – Dachau - Emslandlager. München: C.H. Beck; 2005. pp. 138–140. [Google Scholar]

- Rüther M. Geschichte der Medizin. Ärzte im Nationalsozialismus. Neue Forschungen und Erkenntnisse zur Mitgliedschaft in der NSAP. Dtsch Ärztebl Int. 2001;98:A3264–A3265. [Google Scholar]

- Rüther M. Köln im Zweiten Weltkrieg. Alltag und Erfahrungen zwischen 1939 und 1945. Darstellungen – Bilder – Quellen. Köln: Emons; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Schultka R, Viebig M. The fate of the bodies of executed persons in the Anatomical Institute of Halle between 1933 and 1945. Ann Anat. 2012;194:274–280. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schütz M, Waschke J, Marckmann G, et al. The Munich Anatomical Institute under National Socialism. First results and prospective tasks of an ongoing research project. Ann Anat. 2013;195:296–302. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serup-Bildfeldt K. Stolpersteine vor der Universität und dem Haus Sachsenring 26. ‘Arbeite, als lebtest du ewig. Bete, als müsstest du heute noch sterben’. Professor Benedikt Schmittmann (1872–1939) In: Serup-Bildfeldt K, editor. Stolpersteine. Vergessene Namen, verwehte Spuren. Wegweiser zu Kölner Schicksalen in der NS-Zeit. Mit einem Beitrag von Elke Heidenreich. 2nd edn. Köln: Kiepenheuer & Witsch; 2004. pp. 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Stöckel S. Sozialmedizin im Spiegel ihrer Zeitschriftendiskurse. Von der Monatsschrift für soziale Medizin bis zum Öffentlichen Gesundheitsdienst. In: Schagen U, Schleidermacher S, editors. 100 Jahre Sozialhygiene, Sozialmedizin und Public Health in Deutschland. Berlin: CD-Rom; 2005. pp. 3–35. [Google Scholar]

- Süss W. Der ‘Volkskörper’ im Krieg. Gesundheitspolitik, Gesundheitsverhältnisse und Krankenmord im nationalsozialistischen Deutschland 1939–1945. München: R. Oldenbourg; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Thiesen S. Strafvollzug in Köln 1933–1945. Eine Studie zur Normdurchsetzung während des Nationalsozialismus in der Straf- und Untersuchungshaftanstalt Köln-Klingelpütz. Berlin: Lit; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ude-Koeller S, Knauer W, Viebahn C. Anatomical practice at Göttingen University since the age of enlightenment and the fate of victims from Wolfenbüttel prison under Nazi rule. Ann Anat. 2012;194:304–313. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viebig M. Zu Problemen der Leichenversorgung des Anatomischen Institutes der Universität Halle vom 19. bis Mitte des 20. Jahrhundert. In: Rupieper HJ, editor. Beiträge zur Geschichte der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg. 1502–2002. Halle (Saale): mdv; 2002. pp. 117–146. [Google Scholar]

- Waltenbacher T. Zentrale Hinrichtungsstätten. Der Vollzug der Todesstrafe in Deutschland von 1937–1945. Scharfrichter im Dritten Reich. Berlin: Zwilling-Berlin; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wenge N. Kölner Kliniken in der NS-Zeit. Zur tödlichen Dynamik im lokalen Gesundheitswesen 1933–1945. In: Frank M, Moll F, editors. Kölner Krankenhausgeschichten. Am Anfang war Napoleon. Köln: Locher; 2006. pp. 546–569. [Google Scholar]

- Wüllenweber H. Sondergerichte im Dritten Reich. Vergessene Verbrechen der Justiz. Frankfurt: Luchterhand; 1990. [Google Scholar]