Abstract

The present study was envisaged to investigate the effect of green banana (GBF) and soybean hulls flours (SHF) on the physicochemical characteristics, colour, texture and storage stability of chicken meat nuggets. The addition of GBF and SHF in the nugget formulations was effective in sustaining desired cooking yield and emulsion stability besides nutritional benefits. Protein and fat contents were decreased (p > 0.05), but fibers and ash contents was increased (p < 0.05) amongst treatments. The flour formulated samples were lighter (L* value) less dark (a*) than control. Textural values were affected significantly. On storage, samples with GBF showed lower pH (p > 0.05%) than control and treatments. Lipid oxidation products, however, unaffected (p > 0.05) but increased in all samples over storage time. Flour treatments showed a positive impact in respect to microbiological quality, however, sensory evaluation indicated comparable scores for all attributes at all times. So, incorporation of GBF and SHF in the formulation could improve the quality and storage stability of chicken nuggets.

Keywords: Nuggets, Banana flour, Soybean hulls, Storability

In the recent years, scientific evidence confirming the relationship between food and health necessitated rapid development of formulated meat products which are natural, functional and nutritional as well (Viuda-Martos et al. 2010). Functional meat products are generally produced by reformulation of meat by incorporating health promoting ingredients such as fibres (Hur et al. 2009), proteins (Fernandez-Gines et al. 2005), prebiotics (Wang 2009), probiotics (Vuyst et al. 2008), polyunsaturated fatty acids (Clough 2008), antioxidants (Eim et al. 2008) etc. The diet prevailing in many industrialized countries is characterized by an excess of energy dense food rich in fat, but with a deficiency of complex carbohydrates which constitute major portion of dietary fiber. Fiber in meat improves functionality through their solubility, viscosity, gel forming ability, water-binding capacity, oil adsorption capacity, and mineral and organic molecule binding capacity, which affects product quality and characteristics (Tungland and Meyer 2002). Beside these, high fiber intake tends to reduce risk of colon cancer, obesity, cardiovascular diseases, and several other disorders (Schneeman 1999). However, due to imposition of new food laws concerning the health claims and vast regional differences in the consumption of functional foods growth opportunities remain in the global health market as scientific studies remain uncovered the benefits of both emerging and existing ingredients (Viuda-Martos et al. 2010).

Green banana flour (GBF) and soybean hull flour (SHF) are rich in fibers. SHF contains up to 50% dietary fibers (Batajoo and Shaver 1998), while fiber contents in GBF are 14.0% (Pacheco-Delahaye et al. 2008). A distinctive characteristic of the soy polysaccharide is that it improves textural property through water binding capacity (Lai et al. 2003). As soya hulls increased, its fiber competes for water increasing the viscosity, which causes less shrinkage when added in meat products (Koksel et al. 2004). Antioxidant property of soya proteins is well documented (Das et al. 2008). The water absorption property of banana flours, however, depends on the degree of intermolecular bonding, while swelling power and solubility are temperature dependent, as starch molecule depolymerized by the thermal treatment (Alexander 1995). The banana flour starts to gel formation at initial pasting temperature of 63 °C. GBF is also rich in vitamin C and A, glutathione, flavonoids and phenolics which have potent antioxidant property (Suntharalingam and Ravindran 1993). However their functionality in meat system still needs to be elucidated.

There is no other published literature on the effect of GBF and SHF on chicken nuggets. Therefore, objective of this study was to investigate the effects of GBF and SHF on the physicochemical quality, sensory property and storage stability of chicken nuggets.

Materials and methods

Preparation of green banana and soybean hulls flours

Raw green bananas (Musa paradisica L. subsp. normalis) and soybeans (Glycine max) were purchased from local supermarkets at the time of peak production, after that immediately processed in the laboratory. For green banana flour (GBF), raw bananas were boiled at 95 °C for 5 min and peeled off the rind manually. The edible portion was sliced and then dipped into 0.05% sodium metabisulphite (s. d. Fine Chemicals, Mumbai, India) solution for 2 hrs to prevent enzymatic reaction. Banana slices were washed repeatedly using fresh sodium metabisulphite solution, and finally washed with tap water. After drained off excess liquid, they were oven dried at 60 °C until brittle.

Soybean hulls flour (SHF) was prepared from raw soybean. The raw soybeans were manually peeled off after overnight soaking in tap water. The recovered hulls were boiled in water for 30 min to destroy trypsin inhibitors and haemagglutinins (Kratzer et al. 1990). The water content was removed by draining and squeezing, and finally they were dried in a cabinet dryer (MSW, India) at 60 °C for 14 hrs. Both banana slices and hulls were ground separately in an Inalsa food grinder (Inalsa make, India) to get fine particles of flours.

Chicken meat nuggets formulation and processing

The spent male birds of broiler parent stock (IBL-98) of 32 wks age were slaughtered in the departmental slaughterhouse as per scientific method. The dressed carcases (3.5–4 kg per bird) were chilled at 4 ± 1 °C for overnight, deboned manually, and then divided into small cubes. The meat cubes were then first minced through a 6 mm grinding plate followed by 4 mm plate in a meat mincer (Kalsi motors, Ludhiana, India). Chicken nuggets were manufactured according to standard formulation (only the meat percentages added up to 100% while the percentages of all ingredients are related to meat): 100% lean chicken meat (w/w), 5% chilled water (w/w), 5% refined vegetable oil (w/w), 5% textured soy protein (Nutrela hydrated, 1:3 ) of Ruchi Soya Industries, Mumbai, India (w/w), 3% refined wheat flour (w/w), 3% condiment (onion, garlic and ginger; 3: 1:1) paste (w/w), 3% whole egg liquid (w/w), 1.75% spice mix (w/w), 1.5% sodium chloride (w/w), 0.5% sugar (w/w), 0.2% tetra-sodium pyrophosphate (TSPP, w/w) and 120 mg kg−1 sodium nitrite. This original mixture was used as control sample while GBF and SHF were added alone or in combination with replacement of lean meat. Three experiments were conducted, in which, GBF and SHF were added respectively to experiment 1 and 2 at 3, 4 and 5% level. While in the 3 rd experiment combinations of both the flours were added at GBF, 3% + SHF, 1%; GBF, 2%. + SHF, 2% and GBF, 1%. + SHF, 3%. All batches of minced meat samples were mixed separately with the other ingredients in an Inalsa food blender for 1 min. Salt and TSPP were added first and ice water and refined vegetable oil were added slowly at the time of mixing in Inalsa mixer. Other ingredients also added simultaneously. After complete mixing, meat batters were taken out and filled up in rectangular shape aluminium moulds (20 × 8 × 5 cm3). The filled up moulds were placed in an autoclave and cooked at 6.8 kg pressures, 121 °C temperature for 20 min. The cooked samples were cooled to room temperature, packed in colourless low density polyethylene (LDPE) bags (150–200 gauges, 20 × 10 cm2), sealed and then kept at 4 ± 1 °C before sliced them into nuggets (5 × 2 × 2 cm3) and subsequent quality evaluation. Best treatments selected from each of above three experiments were subjected to storage stability studies at 4 ± 1 °C.

Packaging and storage condition

About 200 g of nugget samples were kept in LDPE bags, sealed aerobically and then stored at 4 ± 1 °C. Three separate batches of nuggets were prepared and analyzed at 5 days interval.

Physicochemical analysis and nutritive value

Emulsion stability of nuggets was determined following the method of Baliga and Madaiah (1970), and pH was measured (Devatkal and Naveena 2010) in meat homogenates prepared with 10 g of sample and distilled water (50 ml), using an Elico pH meter (Model: LI 127). The cooking yield was determined after recording the weight of emulsion before and after cooking, and expressed as percentage. Moisture, protein, fat, total ash and crude fibers were determined following the AOAC (2007) procedures. Total calorie estimates (Kcal) were determined on the basis of 100 g sample using Atwater values for fat (9Kcal/g), protein (4.02Kcal/g) and carbohydrate (3.87Kcal/g) (Mansour and Khalil 1997). The amount of carbohydrate for energy estimates was calculated on the basis of product formulations and composition of added ingredients. The energy value of dietary fiber was considered as per European legislation act by using a conversion factor of 2 Kcal per g of fibre. (Commission Directive 2008/100/EC, 2010). All analyses were performed in duplicate.

Colour profile analysis

Colour profile was measured using Hunter Colour Lab, USA (Mini XE, Portable type) having setting of cool white light (D65) and 2° was used to know Hunter L*, a*, and b* values. Hunter L* value denotes (brightness100) or lightness (0), a* (+redness/−greenness), b* (+yellowness/−blueness) values were recorded on/in a thick slice of whole meat block. The instrument was calibrated using light trap/black glass and white tile provided with the instrument. Then the above colour parameters were selected. The instrument was directly put on the surface of meat product at three different points. Mean and standard error for each parameter were estimated.

Texture profile analysis

Texture profile analysis (TPA) was conducted using Texture analyzer (TA-HDi, Stable Microsystem, UK) at Central Institute of Post Harvest Engineering and Technology, PAU Campus, Ludhiana. Six slices of each sample of 1 × 1 × 1 cm3 was subjected to pretest speed (2 mm/sec), post test speed (5 mm/sec) and test speed (1 mm/sec) with a deformation of 3 mm, time (2 sec) having a load cell of 500 N. A compression platform of 25 mm was used as a probe. The TPA was performed as per the procedure outlined by Rai and Balasubramanian (2009). The parameters determined from the force-time plot were Hardness (N) = maximum force required to compress the sample (second peak, F2); Springiness (cm) was calculated as the distance that the product recovered its height during the time that elapsed between the end of the first compression and the start of the second compression; Cohesiveness (A2/A1) was measured as the ratio of the positive force area during the second compression (A2) to the positive area during the first compression (A1). Chewiness (N cm) was calculated as hardness × cohesiveness × springiness; and Resilience = the ratio of area of A5/A4.

Lipid oxidation

Evaluation of TBARS (n = 6) was performed using TBA test of Witte et al (1970), in which, TCA extract was first filtered through Whatman No. 1 filter paper (s. d. Fine Chemicals, Mumbai, India), and then 3 ml of this filtrate was mixed with 3 ml of 0.005 M TBA reagent, incubated at 27 ± 2 °C under dark, and finally absorbance (O.D.) was taken at 532 nm wavelength using UV-VIS spectrophotometer (Elico make, USA). TBA value was calculated as mg malonaldehyde kg−1 of sample by multiplying O.D. value with K factor 5.2.

Free fatty acids

The method as described by Koniecko (1979) was followed, in which, exactly 5 g of the nuggets was blended with 30 ml of chloroform in the presence of anhydrous sodium sulphate for 2 min. It was then passed through Whatman No. 1 filter paper and filtrate was collected in a 250 ml conical flask. About 2 or 3 drops of 0.2% phenolphthalein indicator solution were added to the chloroform extract, which was titrated against 0.1 N alcoholic potassium hydroxide to get the pink colour end point. The quantity of potassium hydroxide consumed during titration was recorded. Free fatty acids content was calculated and expressed as percentage as following-

|

Microbiological analysis

Conventional methods recommended by American Public Health Association (1984) were used to enumerate microbiological quality of nugget samples. Samples (10 g) were excised from the nuggets with a sterile scalpel and forceps and then homogenized with 90 ml of sterile 0.1% peptone water in a pre-sterilized mortar for 2 min. Standard plate counts were determined on Plate Count Agar (PCA), Coliforms on Violet Red Bile Agar and Staphylococcal spp. were counted on Baird Parker Agar. In all cases, plates were incubated at 37 ± 2 °C for 48 hrs. Psychrotrophic counts were determined on PCA, and the plates were incubated at 4 ± 1 °C for 14 d. Yeast and moulds were determined on Potato Dextrose Agar and plates were incubated ate 25 ± 2 °C for 7 d. Pour plate methods in duplicate (n = 6) were used to analyze the samples. Cultural media were from HiMedia Labouratoeis Ltd., Mumbai, India.

Sensory evaluation

Samples were evaluated by a seven member experienced panel of judges from faculty and postgraduate students of College of Veterinary Science, Guru Angad Dev Veterinary and Animal Sciences University, Ludhiana, India. A Quantitative Descriptive Analysis was carried out for the attributes of appearance and colour, texture, flavour, juiciness and overall acceptability using 8 point scale, where 8 = extremely desirable and 1 = extremely undesirable (Keeton 1983). Rectangular pieces approximately 5 × 2 × 2 cm3 were cut and served to the panel members. Tap water at room temperature was provided to cleanse the palate between samples. The tests were carried out one hour before or two hours after the midday meal. Three sitting (n = 21) were conducted at each time on samples warmed in a microwave oven for 20 sec.

Statistical analysis

Data were interpreted by analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Duncan’s multiple range tests on ‘SPSS-12.0’ software packages as per standard methods of (Snedecor and Cochran 1994). Three replicate experiments were carried out and statistical significance was expressed at the 5% level.

Results and discussion

Physicochemical quality

The results of pH, emulsion stability (ES) and cooking yield (CY) of raw and cooked nugget samples are presented in Table 1. Samples formulated with individual or combination of flours did not affect emulsion pH. Similar trend was also observed in products pH, and in general, comparatively higher pH was noted from samples with SHF which could be attributed due to higher pH of SHF (6.7−6.8) (Sessa 2004). ES which corresponds to CY was also higher for samples from experiment 2 (SHF) than other treatments including control. It is worthwhile to report that with the inclusion of different flours, ES and CY were improved significantly (p < 0.05) as compared to control. CY was higher from the samples with combination of flours though they were not compared statistically. Marked increased in CY and ES amongst the treatments could be attributed due to increase of viscosity by the fibers which ultimately reduces shrinkage on cooking (Lai et al. 2003).

Table 1.

Effects of green banana and soybean hulls flour on the physicochemical quality of chicken meat nuggets

| Emulsion pH | Emulsion Stability (%) | Cooking yield (%)a | Product pH | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment 1 | ||||

| Control (0%) | 6.1 ± 0.01 | 92.0 ± 0.57b | 92.4 ± 0.98b | 6.3 ± 0.01 |

| GBF (3%) | 6.1 ± 0.01 | 93.4 ± 0.48ab | 92.4 ± 1.02b | 6.3 ± 0.01 |

| GBF (4%) | 6.0 ± 0.01 | 94.2 ± 0.49a | 93.5 ± 1.01ab | 6.2 ± 0.01 |

| GBF (5%) | 6.0. ± 0.02 | 94.3 ± 0.37a | 94.2 ± 1.14a | 6.2 ± 0.02 |

| Experiment 2 | ||||

| Control (0%) | 6.0 ± 0.02 | 93.5 ± 0.41b | 91.7 ± 0.55b | 6.3 ± 0.01 |

| SHF (3%) | 6.0 ± 0.02 | 95.1 ± 0.28ab | 92.9 ± 0.45ab | 6.8 ± 0.01 |

| SHF (4%) | 6.1 ± 0.03 | 95.7 ± 0.34a | 93.8 ± 0.41a | 6.3 ± 0.01 |

| SHF (5%) | 6.1 ± 0.02 | 96.3 ± 0.24a | 93.8 ± 0.17a | 6.3 ± 0.02 |

| Experiment 3 | ||||

| Control (0%) | 6.0 ± 0.02 | 93.4 ± 0.33b | 93.7 ± 0.52b | 6.3 ± 0.01 |

| GBF, 3% + SHF, 1% | 6.0 ± 0.01 | 93.8 ± 0.46b | 94.8 ± 0.45a | 6.2 ± 0.02 |

| GBF, 2% + SHF, 2% | 6.1 ± 0.01 | 95.4 ± 0.41a | 95.2 ± 0.28a | 6.2 ± 0.01 |

| GBF, 1% + SHF, 3% | 6.1 ± 0.01 | 95.1 ± 0.21a | 95.0 ± 0.33a | 6.3 ± 0.01 |

n = 6, a n = 3

GBF Green banana flour; SHF Soybean hulls flour

Values with different small case letter superscripts on the same column are significantly different (p < 0.05)

Proximate composition and nutritive value

Data relating to proximate composition and nutritive value are shown in Table 2. It has been observed that addition of GBF and SHF alone or in combinations significantly (p < 0.05) affected moisture content; while protein and fat contents were remained unchanged. Flour combination treatments exhibited higher moisture content than individual ones which could be attributed due to interaction of both the flours improves water retention capacity thereby good gel strength of starch granules. Swelling power and solubility were also imparted good product characteristics. Crude fibers were observed as expected (Table 2). Control samples contained little fiber, and this was due to addition of textured soy proteins (TSP). Amongst the experiments SHF treated samples shown to have highest fiber and ash contents. The highest energy value was calculated from control samples (193.94 -177.33 kcal/100 g). The energy value for GBF, SHF and combination of flour added samples were affected significantly; however effects were non-significant among the treatments of the experiment 1 and 2. Indeed, in respect to controls, approximately 16−17% energy reduction could be possible. This was due to lower content of fats in treated samples, which are most concentrated dietary energy source contributing 9 kcal/g, more than twice that providing by proteins and carbohydrates.

Table 2.

Effects of green banana and soybean hulls flour on the proximate composition of chicken meat nuggets

| Moisture (%) | Protein (%) | Fat (%) | Crude fiber (%) | Ash (%) | Energy value (Kcal/100 g) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment 1 | ||||||

| Control (0%) | 64.5 ± 0.40b | 20.9 ± 0.57a | 11.9 ± 0.60a | 0.5 ± 0.03c | 0.3 ± 0.02d | 193.9 ± 3.2b |

| GBF (3%) | 65.5 ± 0.40ab | 19.8 ± 0.52ab | 9.4 ± 0.41b | 2.8 ± 0.03b | 2.3 ± 0.08c | 173.7 ± 2.9a |

| GBF (4%) | 66.1 ± 0.49ab | 18.8 ± 0.20b | 9.1 ± 0.36bc | 3.0 ± 0.05a | 2.5 ± 0.05b | 169.1 ± 3.1a |

| GBF (5%) | 66.3 ± 0.37a | 18.7 ± 0.21b | 8.8 ± 0.18c | 3.2 ± 0.03a | 2.7 ± 0.07a | 167.5 ± 3.1a |

| Experiment 2 | ||||||

| Control (0%) | 65.9 ± 0.24b | 20.7 ± 0.35a | 10.0 ± 0.05a | 0.6 ± 0.04d | 2.7 ± 0.05b | 177.3 ± 2.9a |

| SHF (3%) | 67.2 ± 0.32a | 19.9 ± 0.27b | 7.8 ± 0.23b | 3.3 ± 0.10c | 2.8 ± 0.07ab | 165.1 ± 3.1b |

| SHF (4%) | 67.0 ± 0.34a | 18.9 ± 0.24b | 7.6 ± 0.07b | 4.1 ± 0.08b | 2.9 ± 0.07a | 160.2 ± 2.8b |

| SHF (5%) | 66.8 ± 0.43a | 18.7 ± 0.29b | 7.4 ± 0.05b | 4.7 ± 0.06a | 3.0 ± 0.09a | 154.9 ± 3.4b |

| Experiment 3 | ||||||

| Control (0%) | 65.4 ± 0.30b | 20.5 ± 0.32 | 9.5 ± 0.60 | 0.6 ± 0.01d | 2.4 ± 0.03b | 183.0 ± 2.1d |

| GBF, 3% + SHF, 1% | 67.9 ± 0.26a | 19.6 ± 0.24 | 9.1 ± 0.25 | 2.8 ± 0.10c | 2.8 ± 0.02a | 166.5 ± 1.8c |

| GBF, 2% + SHF, 2% | 67.4 ± 0.20a | 19.9 ± 0.27 | 8.7. ± 0.25 | 3.3 ± 0.08a | 2.9 ± 0.02a | 160.2 ± 1.5a |

| GBF, 1% + SHF, 3% | 67.7 ± 0.37a | 19.8 ± 0.32 | 9.0 ± 0.14 | 3.2 ± 0.06b | 2.7 ± 0.01a | 161.9 ± 2.1b |

n = 6

GBF Green banana flour; SHF Soybean hulls flour

Values with different small case letter superscripts on the same column are significantly different (p < 0.05)

Texture profile analysis (TPA)

TPA result shows that significant differences were observed in hardness of flour added samples as compared to control (Table 3). However differences were non-significant among the treatments. Higher hardness value could be attributed to the chemical composition of GBF and SHF, which enable them to lose integrity, leaving the products with harder texture. Springiness value was significantly higher for nuggets with SHF. The behavior of gumminess and chewiness was, in general, as expected since these are secondary parameters related to hardness, springiness and cohesiveness. Control samples were showed lower (p < 0.05) gumminess, cohesiveness and chewiness values compared to GBF/SHF formulated products. In most cases, as the product become harder, it was measured as more cohesive, and it is become softer, it was measured as less cohesive. Resilience was comparatively lower for nuggets with GBF.

Table 3.

Effects of green banana and soybean hulls flour on the textural parameters* of chicken meat nuggets

| Hardness | Springiness | Cohesiveness | Gumminess | Chewiness | Resilience | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment 1 | ||||||

| Control (0%) | 18.0 ± 1.1b | 0.82 ± 0.10 | 0.47 ± 0.02b | 8.0 ± 0.81b | 6.4 ± 0.69b | 0.29 ± 0.01a |

| GBF (3%) | 18.4 ± 1.1ab | 0.84 ± 1.09 | 0.48 ± 0.02ab | 8.8 ± 0.41ab | 7.0 ± 0.45ab | 0.24 ± 0.01ab |

| GBF (4%) | 18.9 ± 0.9ab | 0.85 ± 0.01 | 0.48 ± 0.01ab | 9.2 ± 0.52ab | 7.4 ± 0.47ab | 0.23 ± 0.01b |

| GBF (5%) | 20.5 ± 1.0a | 0.87 ± 0.01 | 0.49 ± 0.02a | 9.3 ± 0.33a | 7.7 ± 0.61a | 0.25 ± 0.03ab |

| Experiment 2 | ||||||

| Control (0%) | 18.0 ± 1.1b | 0.81 ± 0.01b | 0.47 ± 0.01 | 8.0 ± 0.81b | 6.4 ± 0.64b | 0.29 ± 0.01 |

| SHF (3%) | 18.5 ± 0.8ab | 0.84 ± 0.02a | 0.47 ± 0.02 | 8.9 ± 0.42b | 6.6 ± 0.39b | 0.28 ± 0.01 |

| SHF (4%) | 19.1 ± 0.8ab | 0.86 ± 0.01a | 0.48 ± 0.01 | 9.7 ± 0.29ab | 6.8 ± 0.48b | 0.28 ± 0.01 |

| SHF (5%) | 20.8 ± 1.0a | 0.88 ± 0.03a | 0.49 ± 0.01 | 10.3 ± 0.54a | 7.0 ± 0.62a | 0.27 ± 0.03 |

| Experiment 3 | ||||||

| Control (0%) | 18.1 ± 1.1b | 0.78 ± 0.02b | 0.46 ± 0.02a | 7.9 ± 0.73ab | 6.4 ± 0.55ab | 0.27 ± 0.01a |

| GBF, 3% + SHF, 1% | 19.5 ± 0.92a | 0.80 ± 0.01b | 0.46 ± 0.01a | 9.1 ± 0.48a | 7.2 ± 0.37a | 0.22 ± 0.01b |

| GBF, 2% + SHF, 2% | 19.9 ± 0.77a | 0.84 ± 0.01a | 0.47 ± 0.02a | 9.5 ± 0.62a | 6.8 ± 0.48a | 0.26 ± 0.01a |

| GBF, 1% + SHF, 3% | 18.2 ± 1.04ab | 0.81 ± 0.01b | 0.43 ± 0.02b | 6.6 ± 0.45b | 6.0 ± 0.64b | 0.27 ± 0.03a |

n = 12

GBF Green banana flour; SHF Soybean hulls flour

Values with different small case letter superscripts on the same column are significantly different (p < 0.05)

*Unit for Hardness = N, Springiness = cm, Cohesiveness = ratio, Gumminess = N, Chewiness = N cm, Resilience = ratio

Hunter colour value

Data for Hunter colour values of the chicken nuggets are presented in Table 4. The lightness (L*) value was significantly (p < 0.05) higher for treated samples than control. This could be attributed due to higher level of white components in the fiber of GBF and SHF. In lightness evaluation, it is important to note that although L* values were greater in all nuggets with added flours in respect to control, the increase of fiber concentrations further did not affect lightness value significantly. Redness (a*) value was significantly (p < 0.05) higher in controls, and this a* behavior is similar to moisture content of the treated samples as the samples with highest moisture content correspond to the samples with lowest a* value. A similar relation between a* value and moisture content has been reported by Fernandez-Gines et al. (2004) in beef bologna. The reduction in redness, however, did not affect yellowness (b*) value in between control and treatments. Samples with 5% added GBF had highest yellowness (b*) values. This indicates that GBF flour had more negative effect than SHF on b* value of chicken nuggets. There are no other literature data on the GBF/SHF, however, result with lentil flour indicated lighter colour (L*) meat balls and their yellowness value only little affected (Serdaroglu et al. 2005).

Table 4.

Effects of green banana and soybean hulls flour on the colour profiles of chicken nuggets

| Lightness (L*) | Redness (a*) | Yellowness (b*) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment 1 | |||

| Control (0%) | 53.6 ± 0.25b | 10.3 ± 0.13a | 17.9 ± 0.18b |

| GBF (3%) | 53.7 ± 0.22b | 10.1 ± 0.11a | 18.2 ± 1.14b |

| GBF (4%) | 53.9 ± 0.27ab | 9.7 ± 0.16a | 18.3 ± 0.59ab |

| GBF (5%) | 54.2 ± 0.09a | 9.4 ± 0.10b | 18.9 ± 0.17a |

| Experiment 2 | |||

| Control (0%) | 53.6 ± 0.25b | 10.3 ± 0.14a | 17.9 ± 0.18 |

| SHF (3%) | 53.9 ± 0.17ab | 9.9 ± 0.08b | 18.1 ± 0.16 |

| SHF (4%) | 54.1 ± 0.19ab | 9.5 ± 0.08b | 18.2 ± 0.18 |

| SHF (5%) | 54.7 ± 0.11a | 9.1 ± 0.07b | 18.3 ± 0.21 |

| Experiment 3 | |||

| Control (0%) | 54.0 ± 0.18b | 10.7 ± 0.21a | 17.6 ± 0.18a |

| GBF, 3% + SHF, 1% | 54.9 ± 0.69a | 9.6 ± 0.19b | 18.2 ± 0.47a |

| GBF, 2% + SHF, 2% | 54.1 ± 0.19ab | 9.8 ± 0.09b | 18.4 ± 0.14a |

| GBF, 1% + SHF, 3% | 54.4 ± 0.17ab | 9.7 ± 0.05b | 18.2 ± 0.15a |

n = 12

GBF green banana flour; SHF Soybean hulls flour

Values with different small case letter superscripts on the same column are significantly different (p < 0.05)

Sensory evaluation

Results of sensory evaluation are presented in Table 5. It is worthwhile to note that neither single nor combinations of flour had additional advantage on sensory attributes of treated nuggets than control. Control samples had significantly (p < 0.05) higher flavour, texture, juiciness and overall acceptability scores than 5% added GBF /SHF. Control samples showed higher acceptability than treated nuggets which could be due to better retention of fat and textural values. Among the treatments, samples with GBF shown to had much influence on the most of the sensory attributes by the taste panel members.

Table 5.

Effects of green banana and soybean hulls flour combinations on the sensory quality* of chicken meat nuggets

| Appearance & colour | Flavour | Texture | Juiciness | Overall acceptability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment 1 | |||||

| Control (0%) | 7.1 ± 0.09 | 7.3 ± 0.10a | 7.4 ± 0.10a | 7.3 ± 0.11a | 7.4 ± 0.10a |

| GBF (3%) | 7.1 ± 0.07 | 7.2 ± 0.10a | 7.4 ± 0.09a | 7.2 ± 0.09a | 7.4 ± 0.07a |

| GBF (4%) | 7.1 ± 0.09 | 7.1 ± 0.05ab | 7.2 ± 0.09ab | 6.9 ± 0.06ab | 7.1 ± 0.04ab |

| GBF (5%) | 7.0 ± 0.09 | 6.8 ± 0.09b | 6.9 ± 0.14b | 6.8 ± 0.12b | 6.9 ± 0.08b |

| Experiment 2 | |||||

| Control (0%) | 7.0 ± 0.09 | 7.0 ± 0.09a | 7.1 ± 0.05a | 7.1 ± 0.07a | 7.0 ± 0.04a |

| SHF (3%) | 6.9 ± 0.09 | 6.8 ± 0.09a | 7.1 ± 0.07a | 6.9 ± 0.08ab | 7.0 ± 0.09a |

| SHF (4%) | 6.9 ± 0.12 | 6.7 ± 0.12ab | 7.1 ± 0.14a | 6.8 ± 0.14ab | 7.0 ± 0.15a |

| SHF (5%) | 6.9 ± 0.13 | 6.6 ± 0.18b | 6.8 ± 0.14b | 6.7 ± 0.15b | 6.7 ± 0.18b |

| Experiment 3 | |||||

| Control (0%) | 7.1 ± 0.14 | 7.1 ± 0.09a | 6.9 ± 0.13 | 6.9 ± 0.12ab | 7.2 ± 0.11a |

| GBF, 3% + SHF, 1% | 7.2 ± 0.09 | 7.1 ± 0.11a | 6.9 ± 0.14 | 6.9 ± 0.14a | 7.1 ± 0.09a |

| GBF, 2% + SHF, 2% | 7.1 ± 0.07 | 6.9 ± 0.11ab | 7.0 ± 0.12 | 6.9 ± 0.14ab | 7.2 ± 0.09a |

| GBF, 1% + SHF, 3% | 7.0 ± 0.11 | 6.6 ± 0.12b | 6.9 ± 0.13 | 6.6 ± 0.14b | 6.7 ± 0.13b |

n = 21, *Based on 8 point descriptive scale, where 8 = extremely desirable and 1 = extremely undesirable

GBF green banana flour; SHF Soybean hulls flour; Values with different small case letter superscripts on the same column are significantly different (p < 0.05)

From the above study it has been observed that among the three different experiments, samples with 4% GBF, 4% SHF and 50:50 combinations of both the flour (GBF, 2% + SHF, 2%) were optimum considering different physicochemical and sensory quality parameters. So they were selected for storage stability study.

Changes in quality during storage at refrigeration (4 ± 1 °C) temperature

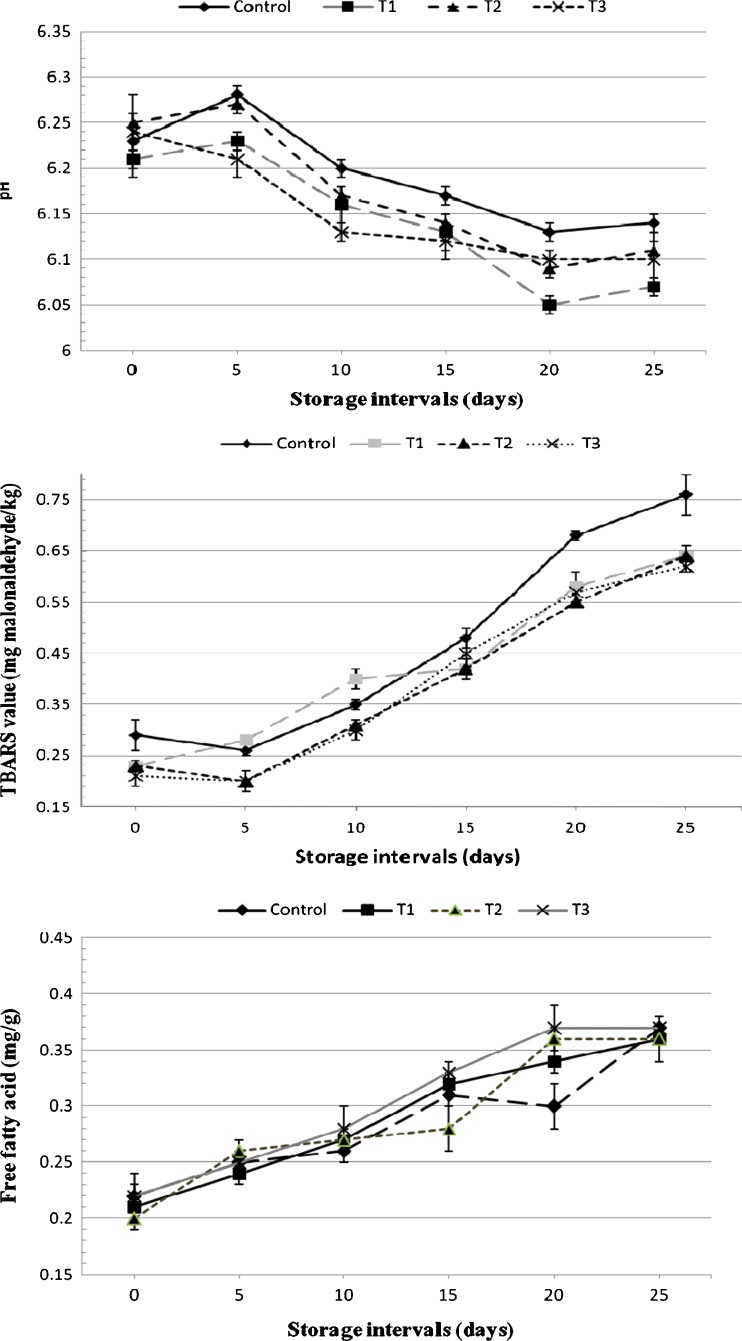

It has been observed that sample types and storage times significantly affected pH of chicken nuggets (Fig. 1), and sample with GBF showed lower pH (p > 0.05%) than control and other treatments. This could be attributed to incorporation of GBF, which inherently exhibit lower pH (~pH 5.1) than lean meat (Tribess et al. 2009). The entire treatments showed nearly similar pH to that of controls, and this could be due to addition of textured soya proteins which buffered the changes in pH irrespective of fiber types. In general, pH value declined (p < 0.05) over storage times, and that was dependent on availability of fermentable carbohydrate by the bacteria (Borch et al. 1996) thereby formation of lactic acid.

Fig. 1.

Chemical changes in chicken nuggets containing green banana flour (GBF) and soyabean hull flour (SHF) during refrigeration (4 ± 1 °C) storage. Control = without added flour, 0%; T1 = GBF, 4%; T2 = SHF, 4% and T3 = GBF: SHF (50:50), 4%

Figure 1 shows controls had highest TBARS value than treatments, however, the value increased (p < 0.05) in all samples with the increase of storage periods. These findings are agreement with the findings of Ho et al. (1997) who reported that chicken sausages treated with carragreenan, soy protein concentrate or antioxidants did not show difference in initial TBARS, but were increased over storage. At the end of the storage, the lowest TBARS were found in T3 sample (0.62 mg malonaldehyde per kg), and this value was much lower than the threshold value of TBARS is around 2.0 mg maloaldehyde/kg (Witte et al. 1970). The increased TBARS values were due to increase of lipid oxidation and production of volatile metabolites during storage (Jo et al. 1999). In fact, the presence of fiber content reduces the free fat thereby decreased the rate of oxidation. Antioxidative property of some fruits and vegetables may also responsible for reduced TBARS value in meat products (Serdaroglu et al. 2005).

Non-significant (p < 0.05) difference was observed in FFA contents amongst the treatments (Fig. 1), however, that were increased in all samples on the day 5 and subsequent storage intervals. Modi et al. (2007) reported that freshly prepared dehydrated chicken kebab mix had FFA values of 0.99%, which gradually (P < 0.05) increased to 1.74% during 6 months of storage. The FFA increased as storage days increases, and according to Kumar et al. (2011) the FFA in green banana flour treated and vacuum packaged chicken meat nuggets was increased due to growth of certain species of bacteria during refrigeration storage. Lower FFA observed in the present study could be attributed to presence of lower level of fat in all the products.

The results of the microbial analysis indicated that standard plate counts (SPC) was lowest (p < 0.05) in controls and samples with 4% added GBF (Table 6). In general, SPC and psychrotrophic counts (PTC) were increased (p < 0.05) with the increase of storage times. PTC were absent in all samples on the day of product preparation, and the counts were detectable on 5th day onwards. Control nuggets had higher PTC than treated nuggets. Similar findings were reported by Kumar et al. (2007) in chicken meat patties. Liu et al. (1991) reported that microbial stability of lean ground beef patties extended with textured soy protein did not differ from control in regards to coliform, aerobic and PTC. Similarly, the aerobic mesophilic counts (AMC) of the buffalo meat nuggets were not influenced by additives (sodium ascorbates, α-tocopherol acetate and sodium tripolyphosphate) and on aerobic packaging (Sahoo and Anjaneyulu 1997). Total Coliform counts, Staphylococcus spp. counts and Yeast and mould counts were detected sporadically during entire storage periods. The sporadic presence of these microbes could be due to post processing contamination. This finding was in agreement with results reported by Biswas et al. (2006) in precooked chicken patties supplemented with curry leave powder.

Table 6.

Effect of green banana and soybean hulls flours on the microbiological quality* of chicken nuggets

| Storage period (days) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | 0 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 |

| Standard plate counts (log cfu/g) | ||||||

| Control | 2.6 ± 0.06e | 2.8 ± 0.09d | 3.1 ± 0.09bc | 3.6 ± 0.07b | 4.1 ± 0.11a | 4.3 ± 0.10aB |

| T1 | 2.6 ± 0.07e | 2.8 ± 0.07d | 3.2 ± 0.05c | 3.6 ± 0.10b | 4.2 ± 0.07a | 4.2 ± 0.10aB |

| T2 | 2.6 ± 0.10e | 2.9 ± 0.03e | 3.2 ± 0.04d | 3.5 ± 0.11c | 4.1 ± 0.09b | 4.4 ± 0.05aA |

| T3 | 2.5 ± 0.08e | 2.8 ± 0.19e | 3.3 ± 0.05d | 3.6 ± 0.06c | 4.2 ± 0.21b | 4.5 ± 0.13aA |

| Psychrotrophic counts (log cfu/g) | ||||||

| Control | ND | 1.9 ± 0.06c | 1.9 ± 0.18cB | 2.4 ± 0.06bA | 2.6 ± 0.07abA | 2.8 ± 0.06aA |

| T1 | ND | 2.0 ± 0.04c | 2.1 ± 0.05bA | 2.2 ± 0.06bB | 2.3 ± 0.04bC | 2.4 ± 0.08aB |

| T2 | ND | 1.0 ± 0.04d | 2.1 ± 0.04dA | 2.2 ± 0.12cB | 2.4 ± 0.03bB | 2.5 ± 0.05aB |

| T3 | ND | 2.1 ± 0.10c | 2.0 ± 0.08cA | 2.1 ± 0.04bC | 2.2 ± 0.06bC | 2.5 ± 0.12aB |

n = 6; ND not detected, * Total Coliforms, Staphylococcus spp. and Yeast and mold were not detected up to 20th day of storage.

Control = without added flour, 0%; T1 = GBF, 4%; T2 = SHF, 4% and T3 = GBF: SHF (50:50), 4%.

Values with different small case letter superscripts on the same row are significantly different (p < 0.05)

Values with different upper case letter superscripts on the same column are significantly different (p < 0.05)

The sensorial characteristics of nuggets samples are showed in Table 7. Treatments had significant (p < 0.05) effect on sensory attributes of developed products. Amongst treatments, T3 had significantly (p < 0.05) lower appearance and colour scores than T1 and that were decreased (p < 0.05) in all samples with the increase of storage periods. The decrease in appearance and colour scores might be attributed due to oxidation of myoglobin and increased loss of moisture. However, increase of fat loss contributed to the reduction of flavour as observed in Table 7. It is well documented that fat content of meat products contribute significantly to their flavour (Pearson and Gillett 1997) and oxidation of that liberated more FFA, amines, malonaldehyde components etc. The reduced moisture and fat content also influence the juiciness and textural attributes. The lower textural scores found in treated nuggets might be due to denaturation of proteins at low pH or degradation of proteins by bacterial action. Matlock et al. (1984) also reported textural scores decline with the extension of storage period, and that were more visible in carragreenan control and carragreenan—soy incorporated products. Ho et al. (1997) reported that the soy protein concentrate results in off-flavour in reduced-fat sausage products after 4 week of refrigeration storage. The overall acceptability of nugget samples also followed the same pattern that observed for other sensory attributes.

Table 7.

Effect of green banana and soybean hulls flours on the sensory attributes* of chicken nuggets

| Storage period (days) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | 0 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 |

| Appearance and colour | ||||||

| Control | 7.0 ± 0.12aA | 7.1 ± 0.13aA | 6.8 ± 0.13bA | 6.4 ± 0.15cA | 6.0 ± 0.17dA | 5.7 ± 0.14eB |

| T1 | 6.9 ± 0.13aA | 6.9 ± 0.12aA | 6.6 ± 0.11bB | 6.4 ± 0.15cA | 6.1 ± 0.23dA | 5.7 ± 0.18eB |

| T2 | 6.7 ± 0.11aAB | 6.7 ± 0.13aB | 6.4 ± 0.10bBC | 6.6 ± 0.22cB | 6.2 ± 0.16cA | 5.9 ± 0.12dA |

| T3 | 6.7 ± 0.14aB | 6.6 ± 0.12aB | 6.3 ± 0.12bC | 6.1 ± 0.14cB | 5.5 ± 0.17dB | 5.4 ± 0.11eC |

| Flavour | ||||||

| Control | 6.8 ± 0.18aA | 6.8 ± 0.14aA | 6.5 ± 0.14bA | 6.4 ± 0.17bA | 5.9 ± 0.20cA | 5.6 ± 0.18dA |

| T1 | 6.7 ± 0.12aA | 6.8 ± 0.16aA | 6.4 ± 0.13bA | 6.5 ± 0.08bA | 5.6 ± 0.21cB | 5.4 ± 0.19dB |

| T2 | 6.8 ± 0.13aA | 6.7 ± 0.15aA | 6.1 ± 0.13bB | 6.1 ± 0.18bB | 5.8 ± 0.15cA | 5.6 ± 0.12dA |

| T3 | 6.6 ± 0.14aB | 6.6 ± 0.14aB | 6.1 ± 0.12bB | 5.9 ± 0.13bC | 5.3 ± 0.22cC | 5.1 ± 0.14dC |

| Texture | ||||||

| Control | 6.9 ± 0.17aA | 6.9 ± 0.12aA | 6.3 ± 0.12bA | 6.2 ± 0.14bA | 6.0 ± 0.21cA | 5.7 ± 0.17dA |

| T1 | 6.8 ± 0.20aA | 6.8 ± 0.16aA | 6.3 ± 0.15bA | 6.1 ± 0.13bA | 5.9 ± 0.21cA | 5.7 ± 0.18dA |

| T2 | 6.7 ± 0.15aA | 6.8 ± 0.18aA | 6.2 ± 0.13bA | 6.1 ± 0.13bAB | 5.8 ± 0.18cA | 5.5 ± 0.11dBC |

| T3 | 6.3 ± 0.22aA | 6.4 ± 0.14aB | 6.3 ± 0.13bA | 5.9 ± 0.11cB | 5.6 ± 0.19dB | 5.4 ± 0.14eC |

| Juiciness | ||||||

| Control | 6.8 ± 0.17aA | 6.6 ± 0.15aA | 6.3 ± 0.10bA | 6.1 ± 0.20cB | 5.7 ± 0.26dA | 5.4 ± 0.21eA |

| T1 | 6.7 ± 0.16aA | 6.7 ± 0.14aA | 6.3 ± 0.16bA | 6.2 ± 0.13bA | 5.5 ± 0.27cB | 5.5 ± 0.23dAB |

| T2 | 6.4 ± 0.17aB | 6.3 ± 0.14aB | 5.9 ± 0.16bB | 5.6 ± 0.18cC | 5.6 ± 0.18cA | 5.3 ± 0.12dA |

| T3 | 6.6 ± 0.20aAB | 6.5 ± 0.16abB | 6.2 ± 0.12bA | 5.8 ± 0.18cC | 5.3 ± 0.21dC | 5.2 ± 0.17eB |

| Overall acceptability | ||||||

| Control | 6.9 ± 0.16aA | 6.8 ± 0.13aA | 6.3 ± 0.12bA | 6.2 ± 0.14bA | 5.8 ± 0.21cA | 5.5 ± 0.13dA |

| T1 | 6.7 ± 0.17aA | 6.7 ± 0.16aA | 6.3 ± 0.10bA | 6.2 ± 0.13bA | 5.7 ± 0.21cA | 5.5 ± 0.17dA |

| T2 | 6.7 ± 0.14aB | 6.5 ± 0.17aAB | 6.2 ± 0.11bAB | 5.9 ± 0.20cB | 5.8 ± 0.17cA | 5.5 ± 0.11dA |

| T3 | 6.4 ± 0.18aB | 6.4 ± 0.16aB | 6.1 ± 0.12bB | 5.8 ± 0.10cB | 5.2 ± 0.15dB | 5.1 ± 0.10eB |

n = 21

*Based on 8 point descriptive scale, where 8 = extremely desirable and 1 = extremely undesirable

Control = without added flour, 0%; T1 = GBF, 4%; T2 = SHF, 4% and T3 = GBF: SHF (50:50), 4%.

Values with different small case letter superscripts on the same row are significantly different (p < 0.05)

Values with different upper case letter superscripts on the same column are significantly different (p < 0.05)

Conclusion

This study suggests that GBF and SHF had potential as good source of dietary fiber which can be successfully used as functional ingredient for chicken nuggets. The addition of green banana and soya hulls to chicken nuggets improved nutritional value, sustained the desired cooking yield and emulsion stability, and helps in improving instrumental textural and colour values. Lipid oxidation products were unaffected (p > 0.05) on storage, but that were increased with the increase of storage times. In respect to microbial quality and sensory attributes, treated samples were comparable with control. So, these flours could find their way in food industry for development of processed meat products.

References

- Alexander A. Pregelatinized starches what are they all about? Cereal Food World. 1995;40:769–770. [Google Scholar]

- Official method of analysis. 16. Washington: Association of Official Analytical Chemists; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Compendium of methods for microbiological examination of foods. Washington: American Public Health Association; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Baliga BR, Madaiah N. Quality of sausage emulsion prepared from mutton. J Food Sci. 1970;35:383–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1970.tb00937.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Batajoo KK, Shaver RD. In situ dry matter, crude protein, and starch degradabilities of selected grains and by-product feeds. Anim Feed Sci Tech. 1998;71:165–176. doi: 10.1016/S0377-8401(97)00132-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas AK, Kondaiah N, Anjaneyulu ASR. Effect of spice mix and curry (Murraya koenigii) leaf powder on the quality of raw meat and precooked chicken patties during refrigeration storage. J Food Sci Tech. 2006;43:438–441. [Google Scholar]

- Borch E, Kant-Muermans ML, Blixt Y. Bacterial spoilage of meat and cured meat products. Int J Food Microbiol. 1996;33:103–120. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(96)01135-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough P. Marketing ω-3 products as nutraceuticals. International Symposium on Fatty acids-Opportunities for Health Education and Investment. 2008;19:233–234. [Google Scholar]

- Commission Directive 2008/100/EC (2010) URL- http://eurlex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2008:285:0009:0012:EN:PDF (Accessed 6 May 2010).

- Das AK, Aujaneyulu ASR, Verma AK, Kondaiah N. Physiochemical, textural, sensory characteristics and storage stability of goat meat patties extended with full fat soy paste and soy granules. Int J Food Sci Tech. 2008;43:383–392. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2006.01449.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Devatkal SK, Naveena BN. Effect of salt, kinnow and pomegranate fruit byproduct powders on colour and oxidative stability of raw ground goat meat during refrigerated storage. Meat Sci. 2010;85:306–311. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2010.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eim VS, Simal S, Rossello C, Femenia A. Effect of addition of carrot dietary fiber on the ripening process of a dry fermented sausage (Sobressada) Meat Sci. 2008;80:173–182. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2007.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Gines JM, Fernandez-Lopez J, Sayas-Barbera E, Sendra E, Perez-Alvarez JA. Lemon albedo as a new source of dietary fiber: application to bologna sausages. Meat Sci. 2004;67:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2003.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Gines JM, Fernandez-Lopez J, Sayas-Barbera E, Perez-Alvarez JA. Meat products as functional foods: a review. J Food Sci. 2005;70:R37–R43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2005.tb07110.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ho KG, Wilson LA, Sebranek JG. Dried Soy Tofu powder effects on frankfurters and pork Sausage Patties. J Food Sci. 1997;62:434–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1997.tb04020.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hur SJ, Lim BO, Park GB, Joo ST. Effect of various fiber additions on lipid digestion during in vitro digestion of beef patties. J Food Sci. 2009;74:C653–C657. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2009.01344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo C, Lee JI, Ahn DU. Lipid oxidation colour changes and volatiles production in irradiated pork sausage with different fat content and packaging during storage. Meat Sci. 1999;51:356–361. doi: 10.1016/S0309-1740(98)00134-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeton JT. Effect of fat and sodium chloride phosphate levels on the chemical and sensory properties of pork patties. J Food Sci. 1983;36:261–276. [Google Scholar]

- Koksel H, Ryu GH, Basman A, Demiralp H, Ng PKW. Effects of extrusion variables on the properties of waxy hull less barley extrudates. Nahrung. 2004;48:19–24. doi: 10.1002/food.200300324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koniecko EK. Handbook for meat chemists. Wayne: Avery Publishing Group Inc.; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Kratzer FM, Bersh S, Vohra P, Ernst RA. Chemical and biological evaluation of soybean flakes autoclaved for different durations. Anim Feed Sci Tech. 1990;31:247–259. doi: 10.1016/0377-8401(90)90129-V. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar RR, Sharma BD, Chatli MK, Chidanandaiah BAK. Storage quality and shelf Life of vacuum packaged extended chicken patties. J Muscle Food. 2007;15:253–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4573.2007.00080.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Biswas AK, Chatli MK, Sahoo J. Effect of banana and soybean hull flours on vacuum-packaged chicken nuggets during refrigeration storage. Int J Food Sci Tech. 2011;46:122–129. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2010.02461.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lai LS, Liu YL, Lin PH. Rheological/textural properties of starch and crude hsiantsao leaf gum mixed systems. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;83:1051–1058. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.1506. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu MN, Huffman DL, Egbert WR, Mc Caskey TA, Liu CW. Soy protein and oil effects on chemical, physical and microbial stability of lean ground beef patties. J Food Sci. 1991;56:906–912. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1991.tb14603.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mansour EH, Khalil AH. Characteristics of low fat beef burgers as influenced by various types of wheat fibers. Food Res Int. 1997;30:199–205. doi: 10.1016/S0963-9969(97)00043-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matlock RG, Terrell RN, Savell JW, Rhee KS, Dutson TR. Factors affecting properties of raw-frozen pork sausages patties made with various sodium chloride/phosphate combinations. J Food Sci. 1984;49(1363–1366):1371. [Google Scholar]

- Modi VK, Sachindra NM, Nagegowda P, Mahendrakar NS, Rao DN. Quality changes during the storage of dehydrated chicken kebab mix. Int J Food Sci Tech. 2007;42:827–835. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2007.01291.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco-Delahaye E, Maldonado R, Perez E, Schroeder M. Production and characterization of unripe plantain flour. Interciencia. 2008;33:290–296. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson AM, Gillett TA. Processed meat. 3. Connecticut: AVI Publishing Co Inc; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Rai DR, Balasubramanian S. Qualitative and textural changes in fresh okra pods (Hibiscus esculentus L.) under modified atmosphere packaging in perforated film packages. Food Sci Technol Int. 2009;152:131–138. doi: 10.1177/1082013208106206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo J, Anjaneyulu ASR. Effects of natural antioxidants and vacuum packing on the quality of buffalo meat nuggets during refrigerated storage. Meat Sci. 1997;47:223–230. doi: 10.1016/S0309-1740(97)00053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneeman BO. Fiber, inulin and oligofructose: similarities and differences. J Nutr. 1999;129:1424S–1427S. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.7.1424S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serdaroglu M, Yildiz-Turp G, Abrodimov Quality of low-fat meatballs containing legume flours extenders. Meat Sci. 2005;90:99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2004.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sessa DJ. Processing of soybean hulls to enhance the distribution and extraction of value-added proteins. J Sci Food Agr. 2004;84:75–82. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.1612. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snedecor GW, Cochran WG. Statistical methods. 8. New Delhi: Oxford and IBH Public Co.; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Suntharalingam S, Ravindran G. Physical and biochemical properties of green banana flour. Plant Food Hum Nutr. 1993;43:19–27. doi: 10.1007/BF01088092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tribess TB, Hernandez-Uribe JP, Mendez-Montealvo MGC, Menezes EW, Bello-Perez LA, Tadini CC. Thermal properties and resistant starch content of green banana flour (Musa cavendishii) produced at different drying conditions. Lebensm-Wiss Technol. 2009;42:1022–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2008.12.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tungland BC, Meyer D. Nondigestible oligo- and polysaccharides (dietary fiber): their physiology and role in human health and food. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2002;3:90–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2002.tb00009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viuda-Martos M, Ruiz-Navajas Y, Fernandez-Lopez J, Perez-Alvarez JA. Effect of orange dietary fiber, oregano oil and packaging conditions on shelf-life of bologna sausages. Food Control. 2010;21:436–443. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2009.07.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vuyst LD, Falony G, Leroy F. Probiotic in fermented sausages. Meat Sci. 2008;80:75–78. doi: 10.1016/j.meatsci.2008.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. Prebiotics: present and future in food science and technology. Food Res Int. 2009;42:8–12. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2008.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Witte VC, Krause GF, Bailey ME. A new extraction method for determining 2-thiobarbituric acid values of pork and beef during storage. J Food Sci. 1970;35:582–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1970.tb04815.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]