Abstract

The coexistence of abnormal keratinization and aberrant pigmentation in a number of cornification disorders has long suggested a mechanistic link between these two processes. Here, we deciphered the genetic basis of Cole disease, a rare autosomal-dominant genodermatosis featuring punctate keratoderma, patchy hypopigmentation, and uncommonly, cutaneous calcifications. Using a combination of exome and direct sequencing, we showed complete cosegregation of the disease phenotype with three heterozygous ENPP1 mutations in three unrelated families. All mutations were found to affect cysteine residues in the somatomedin-B-like 2 (SMB2) domain in the encoded protein, which has been implicated in insulin signaling. ENPP1 encodes ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase 1 (ENPP1), which is responsible for the generation of inorganic pyrophosphate, a natural inhibitor of mineralization. Previously, biallelic mutations in ENPP1 were shown to underlie a number of recessive conditions characterized by ectopic calcification, thus providing evidence of profound phenotypic heterogeneity in ENPP1-associated genetic diseases.

Main Text

Cole disease is a rare autosomal-dominant disorder that has been reported in four families since its original description in 1976.1 The disorder is characterized by congenital or early-onset punctate keratoderma associated with irregularly shaped hypopigmented macules, which are typically found over the arms and legs, but not the trunk or acral regions.1–4 Extracutaneous involvement has not been reported. The pathogenesis of the disorder has remained elusive. Skin biopsies obtained from palmoplantar lesions show hyperorthokeratosis, hypergranulosis, and acanthosis and are therefore not indicative of any specific pathomechanism.2,3 In contrast, upon histopathological examination, hypopigmented areas of the skin demonstrate a reduction in melanin content in keratinocytes, but not in melanocytes, as well as hyperkeratosis and a normal number of melanocytes.4 Accordingly, ultrastructural studies have revealed that melanocytes show a disproportionately large number of melanosomes in the cytoplasm and dendrites but that keratinocytes show a paucity of these organelles, suggestive of impaired melanosome transfer.4

Attempts at identifying the molecular basis of Cole disease through sequencing of candidate genes associated with overlapping phenotypes, such as epidermolysis bullosa simplex with mottled pigmentation (MIM 131960) and Naegeli syndrome (MIM 161000), have failed to reveal causative mutations.2 In the present report, using a genome-wide approach, we demonstrate that mutations in ENPP1 (MIM 173335), encoding ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase 1 (ENPP1),5 underlie Cole disease.

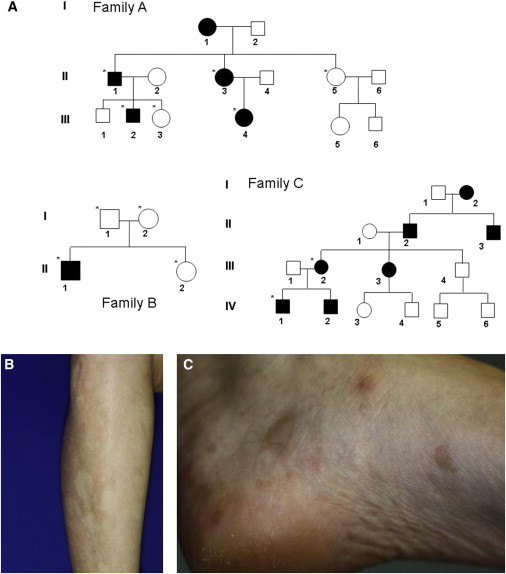

We studied three families affected by the disorder (Figure 1A). Families A and C are of French origin and have not been reported previously. Family B has been previously described2 and originates from the United States. All affected individuals displayed similar clinical and histopathological features, as detailed in Table 1. In brief, affected individuals developed hypopigmented macules mainly located over the extremities and hyperkeratotic papules over the palms and soles (Figures 1B–1C). Age of onset varied between 3 months and 1 year.

Figure 1.

Clinical Features

(A) Pedigrees of the three families affected by Cole disease. Black symbols denote affected individuals. Individuals who were genotyped for mutations in ENPP1 are marked with an asterisk.

(B) Hypopigmented macules over the left forearm of individual III-4.

(C) Hyperkeratotic papules over the left foot of individual III-4.

Table 1.

Clinical and Laboratory Features in Families Affected by Cole Disease

|

Family A |

Family B |

Family C |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| II-1 | II-3 | III-2 | III-4 | II-1 | III-2 | IV-1 | IV-2 | |

| Hypopigmented macules (age of onset) | 6 months | 6 months | within the first year of life | within the first year of life | birth | 12 months | 12 months | 18 months |

| Punctate palmoplantar keratoderma (age of onset) | within the first year of life | within the first year of life | within the first year of life | within the first year of life | 3 months | within the first year of life | within the second year of life | within the second year of life |

| Ectopic calcification | none | early-onset calcific tendinopathy of shoulders, wrists, hips, and heels; microcalcifications on mammography; one large splenic calcification | none | early-onset calcific tendinopathy of shoulders, wrists, hips, and heels | calcinosis cutis (also identified on histology) | none | calcinosis cutis | none |

| Serum phosphate levels | ND | ND | normal | normal | normal | normal | ND | ND |

| Fasting glucose levels | ND | ND | normal | normal | normal | normal | ND | ND |

| Other features | ND | ND | ND | normal insulin levels | normal IGF-1 levels; negative urine glucose; transient blisters on soles at birth; short stature | ND | ND | ND |

The following abbreviation is used: ND, not done.

All participants provided written informed consent to participate in this study according to a protocol reviewed and approved by our institutional review boards. Genomic DNA was extracted either from whole-blood samples with the 5 Prime ArchivePure DNA Blood Kit (5 PRIME) or from saliva collection kits (DNA Genotek). To identify the causative mutations underlying Cole syndrome in our families, we used DNA samples from individuals II-1, II-3, III-2, and III-4 from family A and from individual II-1 from family B for whole-exome capture and next-generation sequencing. Exome sequencing was performed by Macrogen (family A) or by Galil Genetic Analysis (family B) with the same methodology. Whole-exome capture was done by in-solution hybridization with TruSeq (Illumina) and subsequent massive parallel sequencing (Illumina HiSeq2000) with 100 bp paired-end reads. Reads were aligned to GRCh37 (UCSC Genome Browser hg19) with the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner.6 Duplicate reads, resulting from PCR clonality or optical duplicates, and reads mapping to multiple locations were excluded from downstream analysis. Reads mapping to a region of known or detected indels were realigned for minimizing alignment errors. Single-nucleotide substitutions and small indels were identified and quality filtered with the Genome Analysis Toolkit.7 Rare variants were identified by filtering using the data from dbSNP135, the 1000 Genomes Project, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Exome Sequencing Project Exome Variant Server, and an in-house database of 110 sequenced individuals. Variants were classified by predicted protein effects with PolyPhen-28 and SIFT.9 Exome sequencing details are summarized in Table S1, available online.

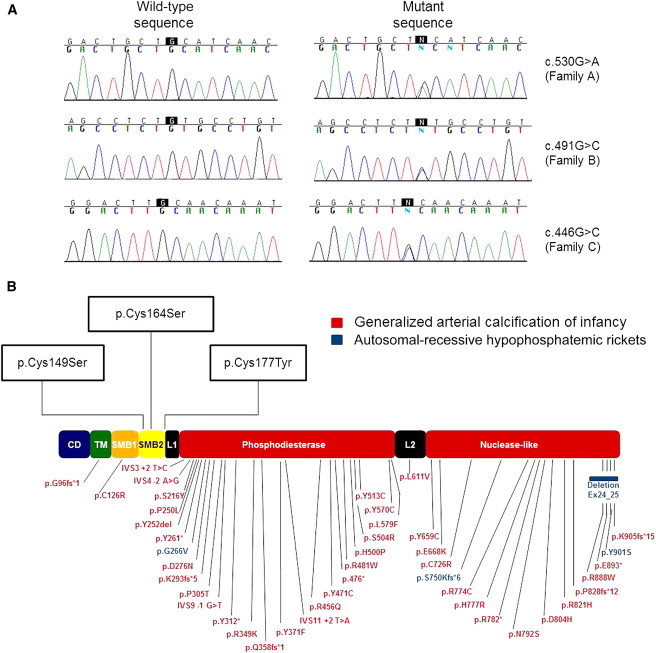

After filtering out variants with a minor allele frequency greater than 0.01 or variants covered less than 10×, we identified a total of 275 variations present in affected individuals of both families. We then assumed that given the separate origins of families A and B, causative mutations should be different in each of them. This approach narrowed our list of variations to nine nucleotide substitutions, which we confirmed by direct sequencing. We then proceeded by establishing the coding sequence of each gene containing one of these nine variations in family C. Among these genes, ENPP1 (RefSeq accession number NM_006208.2) was the only one found to harbor three distinct mutations: c.530G>A (p.Cys177Tyr) was identified in family A, c.491G>C (p.Cys164Ser) was discovered in family B, and c.446G>C (p.Cys149Ser) was detected in family C (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Mutation Analysis

(A) Direct sequencing of ENPP1 revealed three heterozygous mutations in exon 4 of the gene: c.530G>A in family A, c.491G>C in family B, and c.446G>C in family C.

(B) ENPP1 mutations cataloged in the Human Gene Mutation Database and mutations causing Cole disease are marked along a schematic representation of ENPP1. All three mutations causing Cole disease uniquely affect cysteine residues located within the SMB2 domain of ENPP1.

ENPP1 encodes ENPP1, a cell-surface protein that catalyzes the hydrolysis of ATP to AMP and generates extracellular inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi).10 Biallelic mutations in ENPP1 have been shown to be associated with several inherited disorders featuring either ectopic calcifications or abnormal calcium handling, including generalized arterial calcification of infancy (MIM 208000),11 pseudoxanthoma elasticum (MIM 264800),12 and autosomal-recessive hypophosphatemic rickets type 2 (MIM 613312)13. Despite the fact that ENPP1 has not been shown to date to have any role in epidermal differentiation or skin pigmentation, four findings support the notion that the mutations we identified in this gene underlie Cole disease in the three families we studied: (1) none of the three mutations was found in dbSNP, the Human Gene Mutation Database, the UCSC Genome Browser, 1000 Genomes, Ensembl, or the NHLBI Exome Variant Server, including exome sequencing data for a total of 6,503 individuals; (2) using direct sequencing of ENPP1 in all (healthy and affected) participants (Figure 1A), we confirmed cosegregation of the mutations with the disease phenotype in each of the three families (not shown); (3) both the SIFT and the PolyPhen-2 protein-structure prediction programs were found to attribute a maximal damaging score to all three mutations (Table S2); and (4) the three mutations identified affect highly conserved cysteine residues (Table S2).

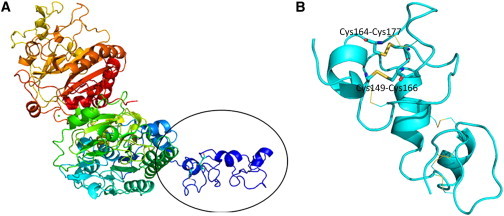

The fact that all three mutations affected residues located within a small region of ENPP1 (Figure 2B) supports a role for this domain in the pathogenesis of the disease. ENPP1 structure has been determined for M. musculus14 (Protein Data Bank [PDB] ID 4B56), which is 79% homologous to the human protein. Using the SWISS-MODEL folding engine,15 we built a homology model with subunit A of the 4B56 structure. The resulting model included residues Lys106 to Ser922. Cys149, Cys164, and Cys177, the three cysteines affected by the mutations we identified in our families, are located on a protracted substructure that extends out from the main protein body (Figure 3A) and are involved in intramolecular disulphide bonds: Cys149-Cys166 and Cys164-Cys177 (Figure 3B). Six additional disulphide bonds present in the M. musculus structure are also seen in the model of the human protein (Figure 3B). The conservation of eight disulphide bonds in a small region of the protein indicates the need for precise positioning of the N terminus and also indicates potential redox-regulated control mechanisms. Disruption of these disulphide bonds is expected to impart a large change on the local structure of this portion of the protein and is therefore likely to exert a dominant-negative effect. This contrasts with the mechanisms of action of recessive ENPP1 mutations, which result in loss of ENPP1 expression and/or activity.16

Figure 3.

Protein Modeling

(A) We modeled human ENPP1 (residues Lys106 to Ser922) on the basis of the crystal structure previously determined for the mouse homolog (PDB ID 4B56). Using SWISS-MODEL folding engine 15, we built a homology model with subunit A of the 4B56 structure. The model is spectrally colored from the N terminus (blue) to the C terminus (red). Residues Cys149, Cys164, and Cys177 are located on a protracted substructure that extends out from the main protein body (black oval).

(B) Enlarged view of the encircled region of (A). The protein backbone is in cyan. The intramolecular disulphide bonds involving the altered residues (Cys149-Cys166 and Cys164-Cys177) in Cole disease are depicted as sticks, and C, N, O, and S atoms are colored in cyan, blue, red, and yellow, respectively. Six additional disulphide bonds are represented as thin lines with the same color coding.

The facts that ENPP1 has so far been implicated in the prevention of ectopic calcification16 but that the Cole disease phenotype mainly includes keratoderma and hypopigmentation prompted us to review all clinical data available for affected individuals. Interestingly, individual III-4 of family A had been diagnosed with an early-onset calcific tendinopathy of the shoulders and Achilles tendon with chronic activity-related pain, and individual II-3 of family A also presented with wrist calcification suggestive of chondrocalcinosis and unusual numerous breast microcalcifications detected on a mammography performed at 53 years of age (Table 1). In addition, calcified deposits in the dermis of the plantar surface were present in individual II-1 of Family B, as previously reported.2 Although these data lend further support to the pathogenic role of ENPP1 mutations in Cole disease, they do not explain their unique clinical manifestations.

ENPP1 consists of eight domains (Figure 2B).14 Most mutations associated with ectopic calcification affect the phosphodiesterase domain, which is thought to mediate ENPP1 catalytic activity, or the nuclease domain.13 In contrast, all three mutations identified as causing Cole disease in this study affect residues clustered within the somatomedin-B-like 2 (SMB2) domain of ENPP1 (Figure 2B), suggesting that this domain plays a role in the regulation of epidermal pigmentation and differentiation. ENPP1 belongs to a family of seven ectonucleotide pyrophosphatases/phosphodiesterases, only three of which possess the SMB2 domain.17

Not only does ENPP1 negatively regulate mineralization by hydrolyzing extracellular nucleoside triphosphates to produce PPi, but it has also been shown to inhibit insulin signaling18 through the interaction between its SMB2 domain and insulin receptor.19 These observations might be of direct relevance to the pathogenesis of Cole disease. Indeed, insulin signaling plays a critical role in epidermal homeostasis20 and interacts with other systems important for keratinocyte differentiation, including epidermal-growth-factor-dependent signaling21 which has been implicated in the pathogenesis of punctate palmoplantar keratoderma (MIM 148600).22,23 Moreover, as mentioned above, previous histopathological and ultrastructural studies have suggested a block in melanin transfer from melanocytes to keratinocytes as the basis for the development of hypopigmented patches in Cole disease.4 As melanosome uptake by keratinocytes is largely mediated by proteinase-activated receptor 2 (PAR-2),24 and because PAR-2 activity is under the negative regulation of the insulin signaling pathway,25 impaired inhibition of this pathway by ENPP1 is expected to lead to decreased transfer of melanosomes to keratinocytes. Impaired ENPP1 regulation of insulin signaling is expected to be of physiological consequence in the context of specific tissues only as attested by the fact that we could not find any evidence of systemic impaired glucose handling in affected individuals (Table 1).

In summary, our data provide genetic evidence of an unexpected role for ENPP1 in the regulation of epidermal differentiation and pigmentation.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the participation of all family members in this study. This study was supported by a generous donation from the Ram family, National Institutes of Health and National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases grants R01 AR28450 and R21 AR063781, and a gift from the Bohnert Foundation.

Contributor Information

Alain Taieb, Email: alain.taieb@chu-bordeaux.fr.

Eli Sprecher, Email: elisp@tasmc.health.gov.il.

Supplemental Data

Web Resources

The URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

1000 Genomes Project, http://www.1000genomes.org/

The ConSurf Server, http://consurftest.tau.ac.il/

Human Gene Mutation Database, http://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk/ac/index.php

NHLBI Grand Opportunity NHLBI Grand Opportunity Exome Sequencing Project (ESP), https://esp.gs.washington.edu/drupal/

NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project (ESP) Exome Variant Server, http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), http://www.omim.org

PolyPhen-2, http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/

SIFT, http://sift.jcvi.org/

SWISS-MODEL, http://swissmodel.expasy.org/

UCSC Genome Browser, http://genome.ucsc.edu/

References

- 1.Cole L.A. Hypopigmentation with punctate keratosis of the palms and soles. Arch. Dermatol. 1976;112:998–1000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moore M.M., Orlow S.J., Kamino H., Wang N., Schaffer J.V. Cole disease: guttate hypopigmentation and punctate palmoplantar keratoderma. Arch. Dermatol. 2009;145:495–497. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmieder A., Hausser I., Schneider S.W., Goerdt S., Peitsch W.K. Palmoplantar hyperkeratoses and hypopigmentation. Cole disease. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2011;91:737–738. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vignale R., Yusín A., Panuncio A., Abulafia J., Reyno Z., Vaglio A. Cole disease: hypopigmentation with punctate keratosis of the palms and soles. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2002;19:302–306. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2002.00084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldfine I.D., Maddux B.A., Youngren J.F., Reaven G., Accili D., Trischitta V., Vigneri R., Frittitta L. The role of membrane glycoprotein plasma cell antigen 1/ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase phosphodiesterase 1 in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance and related abnormalities. Endocr. Rev. 2008;29:62–75. doi: 10.1210/er.2007-0004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li H., Durbin R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:589–595. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKenna A., Hanna M., Banks E., Sivachenko A., Cibulskis K., Kernytsky A., Garimella K., Altshuler D., Gabriel S., Daly M., DePristo M.A. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adzhubei I.A., Schmidt S., Peshkin L., Ramensky V.E., Gerasimova A., Bork P., Kondrashov A.S., Sunyaev S.R. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat. Methods. 2010;7:248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar P., Henikoff S., Ng P.C. Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nat. Protoc. 2009;4:1073–1081. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goding J.W., Grobben B., Slegers H. Physiological and pathophysiological functions of the ecto-nucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase family. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2003;1638:1–19. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(03)00058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rutsch F., Ruf N., Vaingankar S., Toliat M.R., Suk A., Höhne W., Schauer G., Lehmann M., Roscioli T., Schnabel D. Mutations in ENPP1 are associated with ‘idiopathic’ infantile arterial calcification. Nat. Genet. 2003;34:379–381. doi: 10.1038/ng1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nitschke Y., Baujat G., Botschen U., Wittkampf T., du Moulin M., Stella J., Le Merrer M., Guest G., Lambot K., Tazarourte-Pinturier M.F. Generalized arterial calcification of infancy and pseudoxanthoma elasticum can be caused by mutations in either ENPP1 or ABCC6. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;90:25–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lorenz-Depiereux B., Schnabel D., Tiosano D., Häusler G., Strom T.M. Loss-of-function ENPP1 mutations cause both generalized arterial calcification of infancy and autosomal-recessive hypophosphatemic rickets. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2010;86:267–272. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jansen S., Perrakis A., Ulens C., Winkler C., Andries M., Joosten R.P., Van Acker M., Luyten F.P., Moolenaar W.H., Bollen M. Structure of NPP1, an ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase involved in tissue calcification. Structure. 2012;20:1948–1959. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arnold K., Bordoli L., Kopp J., Schwede T. The SWISS-MODEL workspace: a web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:195–201. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nitschke Y., Rutsch F. Genetics in arterial calcification: lessons learned from rare diseases. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2012;22:145–149. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stefan C., Jansen S., Bollen M. NPP-type ectophosphodiesterases: unity in diversity. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2005;30:542–550. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maddux B.A., Goldfine I.D. Membrane glycoprotein PC-1 inhibition of insulin receptor function occurs via direct interaction with the receptor alpha-subunit. Diabetes. 2000;49:13–19. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kato K., Nishimasu H., Okudaira S., Mihara E., Ishitani R., Takagi J., Aoki J., Nureki O. Crystal structure of Enpp1, an extracellular glycoprotein involved in bone mineralization and insulin signaling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:16876–16881. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208017109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stachelscheid H., Ibrahim H., Koch L., Schmitz A., Tscharntke M., Wunderlich F.T., Scott J., Michels C., Wickenhauser C., Haase I. Epidermal insulin/IGF-1 signalling control interfollicular morphogenesis and proliferative potential through Rac activation. EMBO J. 2008;27:2091–2101. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Edmondson S.R., Murashita M.M., Russo V.C., Wraight C.J., Werther G.A. Expression of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3) in human keratinocytes is regulated by EGF and TGFbeta1. J. Cell. Physiol. 1999;179:201–207. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199905)179:2<201::AID-JCP10>3.0.CO;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giehl K.A., Eckstein G.N., Pasternack S.M., Praetzel-Wunder S., Ruzicka T., Lichtner P., Seidl K., Rogers M., Graf E., Langbein L. Nonsense mutations in AAGAB cause punctate palmoplantar keratoderma type Buschke-Fischer-Brauer. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2012;91:754–759. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pohler E., Mamai O., Hirst J., Zamiri M., Horn H., Nomura T., Irvine A.D., Moran B., Wilson N.J., Smith F.J. Haploinsufficiency for AAGAB causes clinically heterogeneous forms of punctate palmoplantar keratoderma. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:1272–1276. doi: 10.1038/ng.2444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boissy R.E. Melanosome transfer to and translocation in the keratinocyte. Exp. Dermatol. 2003;12(Suppl 2):5–12. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0625.12.s2.1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hyun E., Ramachandran R., Cenac N., Houle S., Rousset P., Saxena A., Liblau R.S., Hollenberg M.D., Vergnolle N. Insulin modulates protease-activated receptor 2 signaling: implications for the innate immune response. J. Immunol. 2010;184:2702–2709. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.