Abstract

We present the most comprehensive comparison to date of the predictive benefit of genetics in addition to currently used clinical variables, using genotype data for 33 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in 1,547 Caucasian men from the placebo arm of the REduction by DUtasteride of prostate Cancer Events (REDUCE®) trial. Moreover, we conducted a detailed comparison of three techniques for incorporating genetics into clinical risk prediction. The first method was a standard logistic regression model, which included separate terms for the clinical covariates and for each of the genetic markers. This approach ignores a substantial amount of external information concerning effect sizes for these Genome Wide Association Study (GWAS)-replicated SNPs. The second and third methods investigated two possible approaches to incorporating meta-analysed external SNP effect estimates – one via a weighted PCa ‘risk’ score based solely on the meta analysis estimates, and the other incorporating both the current and prior data via informative priors in a Bayesian logistic regression model. All methods demonstrated a slight improvement in predictive performance upon incorporation of genetics. The two methods that incorporated external information showed the greatest receiver-operating-characteristic AUCs increase from 0.61 to 0.64. The value of our methods comparison is likely to lie in observations of performance similarities, rather than difference, between three approaches of very different resource requirements. The two methods that included external information performed best, but only marginally despite substantial differences in complexity.

Keywords: prostate cancer, genetic clinical risk prediction, genetic scores, Bayesian logistic regression, predictive assessment

INTRODUCTION

Risk prediction is a key component to understanding disease outcomes and recommending therapeutic strategies. Current prediction tools for prostate cancer [PCa (MIM 176807)] include only clinical biomarkers without consideration of genetic information. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level has been the most widely used clinical predictor of PCa and is routinely evaluated in men over 50 years old [Schroder et al., 2009; Thompson et al., 2008]. Higher PSA levels, often detected in the presence of a tumour, are commonly used by clinicians to determine whether to perform a biopsy of the prostate despite the knowledge that elevated PSA is associated with other aetiologies unrelated to cancer. Some improvement in prediction of PCa by clinical variables occurred with the development of the Cancer of the Prostate Risk Index (CAPRI) test [Optenberg et al., 1997] and later the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial (PCPT) multivariate risk calculator, which included age, family history of PCa, race, prior biopsy results and digital rectal examination (DRE) results [Thompson et al., 2006]. However, even when PSA is combined with other common clinical variables, such as age, family history, prostate volume and DRE, prediction of PCa remains challenging, with area under the receiver-operating-characteristic (ROC) curve estimates (AUCs) ranging from approximately 0.61 to 0.70 depending upon patient characteristics [Hernandez et al., 2009; Nguyen et al., 2010]. New risk calculators are being developed that include additional biomarkers such as PCA3 level [Vlaeminck-Guillem et al., 2010] but further improvement is needed.

With the huge advances in identification of genetic risk factors for diseases in the past 10 years, studies have begun to evaluate if a combination of genetic risk factors (i.e. genetic scores) alone [Lango et al., 2008; Paynter et al., 2010; Zheng et al., 2008] or in combination with clinical variables [Hsu et al., 2010; Lin et al., 2009; Meigs et al., 2008; Wacholder et al., 2010; Xu et al., 2009; Zheng et al., 2008] can predict risk for a range of complex diseases. In general, results have indicated only marginal predictive benefits from incorporating genetics into clinical risk prediction. However, as of yet, analyses of the predictive benefit of genetic markers for PCa, over existing clinical parameters, have been inconclusive due to sub-optimal retrospective designs, with population sampled controls and clinical measurements only available for cases from diagnosis [FitzGerald et al., 2009; Hsu et al., 2010; Salinas et al., 2009; Xu et al., 2009; Zheng et al., 2008]. Since most of the cases in these studies would only have been biopsied due to elevated PSA measurements, and controls were not matched on PSA, the association between the leading clinical predictor PSA and PCa is biased upwards. Therefore accurate comparison in predictive performance between genetics and PSA has not previously been possible. Due to the availability of baseline clinical and genetic parameters and study-mandated PCa biopsies for all subjects at year 4, by analysing the placebo arm of the REDUCE trial, we were able to make the first direct assessment of the predictive performance of genetic markers over existing clinical variables. Furthermore, we incorporate more genetic information than any previous study using 33 GWAS-replicated single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and that means our work represents the most comprehensive assessment to date of the predictive benefit of genetic markers for PCa.

Recent publications have highlighted both the utility and the hurdles faced in combining genetic scores with clinical parameters for such widely divergent diseases as type 2 diabetes [Lin et al., 2009; Meigs et al., 2008] and breast cancer [Wacholder et al., 2010]. In particular for PCa, the methods for incorporating genetic and clinical variables into predictive scores vary as do results from these studies [Hsu et al., 2010; Xu et al., 2009; Zheng et al., 2008]. Relatively, few publications compare genetic scores obtained with different methodologies with the same clinical populations [Hsu et al., 2010] resulting in little information being available to fully evaluate advantages and disadvantages of distinct methods for generating genetic scores. Therefore, in addition to performing a comprehensive assessment of the predictive benefit of genetic markers for PCa, we compared three statistical methods for incorporating genetics into PCa prediction in combination with clinical variables. Each method used the same clinical variables (age, family history of PCa, PSA, prostate volume and the number of cores in PCa negative baseline biopsy), alongside genetic information from 33 PCa risk-associated SNPs. The first method, widely used previously, uses logistic regression in the current data set, including terms for every SNP alongside clinical covariates. However, the majority of SNPs considered here have been identified and replicated in GWAS, meaning a wealth of external information was available from meta-analyses of effect sizes reported in the literature. The second and third methods took alternative approaches to incorporating this external information. The second method was based on a weighted genetic risk algorithm, which makes use of odds ratio (OR) estimates from external metaanalyses for each of the SNPs. Similar techniques have been used elsewhere [Kim et al., 2010; Lin et al., 2009]. The third method took an alternative Bayesian approach, incorporating the external information via informative priors in a logistic regression framework. This represents a novel application of Bayesian methodology to a genetic risk-score prediction problem.

METHODS

ETHICS STATEMENT

The protocol was approved by the institutional review board at each research site, and all participants provided written informed consent.

STUDY POPULATION

Genetic samples were obtained from the 1547 Caucasian men enrolled in the placebo arm of a 4 year, randomised, double blind, placebo-controlled, international study (28 countries) evaluating the safety and efficacy of dutasteride for the prevention of PCa (The REduction by DU-tasteride of prostate Cancer Events, REDUCE®) who consented to genetic analyses, had a negative biopsy at baseline and at least one post-baseline biopsy. Inclusion criteria, clinical assessments for the determination of clinical variables and demographic information for patients enrolled in this study have been described before [Andriole et al., 2010]. Briefly, men participating in this study had an increased risk for PCa, as defined by age ranging from 50 to 75 years, elevated PSA levels (> 2.5 to 10.0 ng/mL) and a previous biopsy of 6 to 12 cores, which was negative for PCa within 6 months of enrolment. Participants agreed to have study-mandated 10-core transrectal, ultrasound guided prostate biopsies at years 2 and 4. For-cause biopsies could be performed as clinically indicated.

Baseline demographic data that were used for clinical variables for all of the white subjects who participated in the REDUCE study and received at least one on-treatment biopsy (n = 6,157) and for the subset of these subjects from the placebo arm who provided informed written consent for genetic analysis (n = 1,547) are presented in Table I. The distributions of these demographic variables for patients providing genetic samples were comparable to patients in the entire REDUCE study reported by Andriole et al. [2010]. The 1,547 subjects in the genetic analysis collection that were randomised to the placebo arm are summarised by PCa status in Table S1 in Supplementary Material.

TABLE I.

Clinical, demographic and genetic score of white subject in the study

| Subject collection |

Treatment arm in genotyped collection |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | ITT | Genotyped | P-valuea | Dutasteride | Placebo |

| Subjects, (n) | 6,157 | 3,140 | 1,547 | 1,593 | |

| Age at baseline, mean (SD) | 62.7 (6.0) | 62.8 (6.0) | 0.43 | 63.0 (6.0) | 62.6 (6.0) |

| Positive family history at baseline, (n) (proportion) | 818 (0.13) | 418 (0.13) | 0.97 | 216 (0.14) | 202 (0.13) |

| PSA (ng/mL) at baseline | |||||

| Total PSA level, mean (SD) | 5.93 (1.92) | 5.89 (1.90) | 0.049 | 5.91 (1.91) | 5.87 (1.89) |

| PSA ratio, mean (SD) | 0.17 (0.06) | 0.17 (0.06) | 0.14 | 0.17 (0.06) | 0.16 (0.06) |

| Prostate volume (mL) at baseline, mean (SD) | 45.5 (17.4) | 46.6 (17.6) | 6.2 × 10−7 | 47.1 (17.5) | 46.1 (17.7) |

| Number of cores in baseline biopsy, mean (SD) | 8.7 (2.4) | 8.5 (2.4) | 7.0 × 10−14 | 8.5 (2.4) | 8.5 (2.4) |

| PCa positive biopsy, (n) (proportion) | 1,385 (0.22) | 698 (0.22) | 0.63 | 300 (0.19) | 398 (0.25) |

White subjects were recruited across Europe, Australia, New Zealand, North and South America.

The P-values are for comparisons of the 3,140 subjects in the genotyped with the 3,017 subjects in the ITT collection that are not in the genotyped collection. The t-test was used for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables.

SNP SELECTION AND META-ANALYSES

GWAS have identified many SNPs associated with risk for PCa, a substantial number of which have been independently replicated [Easton and Eeles, 2008]. We selected a panel of 33 PCa risk-associated SNPs, each of which was originally identified in GWAS studies at P < 10−7 and for which associations have been confirmed in independent studies [Amundadottir et al., 2006; Duggan et al., 2007; Eeles et al., 2008, 2009; Gudmundsson et al., 2007a, 2007b; Thomas et al., 2008; Yeager et al., 2007, 2009]. This panel of SNPs was genotyped using the Sequenom MassARRAY (Sequenom, San Diego, CA) platform. On each 96-well plate, one duplicated CEPH and two water samples were included. Concordance rate between genotype calls of the duplicated CEPH samples for all SNPs was 100%.

RS numbers for the 33 SNPs, known genes and meta-analysed effect estimates (allelic ORs with 95% confidence intervals) that were used to construct the Bayesian prior distributions described below, may be found in Table S2 in Supplementary Material.

PREDICTIVE MODELS

All predictive models were fitted and assessed using the 1,547 Caucasian men randomised to the placebo group. In order to assess the relative predictive improvement of genetics in addition to commonly used clinical variables, all models included terms from data collected at baseline for age, family history, free:total PSA ratio (from here on referred to as ‘PSA ratio’) and prostate volume. Each of these clinical variables are well known to associate with PCa risk [Gion et al., 1998; Optenberg et al., 1997; Serfling et al., 2007; Thompson et al., 2007]. Furthermore, all models were adjusted for the number of biopsy cores used in the measurement of PCa emergence, as a potential confounder (more biopsy cores would increase the chance of detection) – we decided a priori to adjust for this variable regardless of statistical significance. Our objective was to analyse PCa detected via study mandated biopsy as in Andriole et al’s previous analysis of the same subjects [Andriole et al., 2010]. While more detailed time to event data (other than the study mandated 2- and 4-year time points) were available for a subset of subjects who underwent ‘for-cause’ biopsies during the trial, survival models were avoided since any use of a ‘for-cause’ endpoint would hamper our ability to directly assess the predictive ability of the clinical variables, as explained in the introduction. Furthermore, integrating external information was a key part of our analysis, all of which was in the form of OR estimates – relating these to hazard ratios was beyond the scope of the work presented here. We have therefore used logistic regression for all predictive frameworks to model PCa emergence as measured by study mandated 4-year biopsy, as a binary outcome. After assessing the improvement in model fit owing to genetics for each score, several techniques were used to investigate the improvement in discriminatory power that genetic information added to each score. First, calibration for each score, with and without genetics, was investigated by splitting the subjects into deciles of predicted risk and plotting the average predicted risk against observed risk across the deciles. For a perfectly calibrated score, points would exactly follow a 45-degree line. Second, ROC curve analysis was carried out. Every point on the ROC curve corresponds to use of a different cutoff in model-predicted risk to predict case, or PCa positive, status. For each cut-off, the y- and x- axes show the rate of predicted cases that are true positives and the rate of false positives, respectively. An AUC of 1 corresponds to the existence of a cut-off in predicted risk that perfectly discriminates true disease status. Discriminatory benefit is important to consider in addition to model fit, which demonstrates whether or not the inclusion of genetics results in ORs that are significantly different from one. A covariate may have a significant OR, but add little discriminatory benefit if that OR is close to one [Jakobsdottir et al., 2009]. For each method, ROC curves were fitted with and without genetic information, and the AUCs were compared. We note here that a limitation of such inference is that the AUCs are average performance measures across all possible risk cut-offs, some of which have no practical relevancy. Therefore, it is important to consider such inference alongside other measures of predictive performance such as those suggested here. Finally, the Positive Predictive Value (PPV) was plotted against sensitivity for each score, with and without genetic information. The PPV is defined as the proportion of the individuals diagnosed positive by a given cut-off who truly do have PCa. Sensitivity is defined as the proportion of the subjects who truly have PCa who will be diagnosed positive by a given risk cut-off. Ideally, a cut-off will exist for a test that results in high PPV, while maintaining an acceptable sensitivity. Maximising PPV is of particular value for a PCa score, since biopsies from incorrect diagnoses carry risk and financial burden for the patient.

To obtain unbiased assessment of the ROC, PPV and calibration, 10-fold cross-validation was used for each of these analyses. Ten-fold cross validation randomly divides the data into 10 (roughly) equal subsets and repeatedly uses nine subsets for model fitting (training) and the remaining subset for validation (testing), i.e. to calculate the ROC, PPV and calibration statistics. This process is repeated until each of the 10 subsets has been used exactly once as validation data, after which ROCs, PPVs and calibration statistics were averaged across results from each of the 10 validation sets.

METHOD 1 – FREQUENTIST LOGISTIC REGRESSION

Under the first method, models were fitted using hierarchical logistic regression, with random intercepts by country. Individual terms were included for each of the 33 SNPs, along with terms for age, family history, number of biopsy cores, prostate volume and PSA ratio. For subject i, let Ri, Agei, Coresi, Voli, PSAi, FHi and be their geographical region, age (years), PSA ratio, number of biopsy cores, prostate volume, family history indicator and genotype at marker m, respectively. Let Di define PCa status. A logistic regression models their disease risk as follows:

where

| (1) |

The β terms define log-ORs corresponding to a one unit increase for each variable. Consequently, the βm terms define the additive log-ORs for the minor allele of each SNP. The country-specific intercepts αRi are included to account for possible variability by country, and they are modelled hierarchically around a global mean

| (2) |

where is a measure of the between region variability in cancer prevalence. Maximum likelihood estimates (MLEs) for the log-ORs and the global intercept, α, were obtained using the Expectation Maximization (EM) algorithm, carried out using the GLMER package in R. After obtaining MLEs for all of the parameters, a risk prediction for a new subject j was made as the inverse of their corresponding linear predictor:

| (3) |

Ten-fold cross-validation was used to assess predictive performance without bias.

METHOD 2 – USING META-ANALYSIS INFORMATION VIA A WEIGHTED SCORE

Under the second method, models were also fitted using hierarchical logistic regression. However, a single-weighted genetic score for each patient, constructed from the markers and their PCa risk estimates, was included in the model, rather than individual terms for each of the M markers. This method for producing a genetic score and the procedure used to construct it has been described elsewhere [Kim et al., 2010]. In brief, for each patient, the weighted genetic score is defined as the sum of the number of risk alleles carried for each of the M markers, each weighted by their corresponding ORs as estimated from the meta-analysis of external data. Continuing the notation above and introducing the term WSi, for the weighted genetic score for individual i, the linear predictor becomes

The new term, βWS, defines the log-OR for a one-unit increase in the weighted score. The predicted risk for a new subject, j, is then obtained by taking the inverse-logit of their linear predictor, based on the MLEs. As in method 1,10-fold cross-validation was used to determine the predictive risk for each of the individuals, and risk prediction was assessed in the placebo group.

It should be noted that inclusion criteria for this clinical study specified enrolment only of patients at elevated risk for progression to PCa (based on the clinical variables: age, PSA level and existent biopsy). Therefore, SNP effects in the general population, meta-analyses of which were used to construct the weighted score, may differ in the REDUCE subjects.

METHOD 3 – BAYESIAN LOGISTIC REGRESSION

A Bayesian logistic regression model, which incorporates PCa effect estimates from the external meta-analysis into a logistic regression model via informative priors, was fitted using the same linear predictor and hierarchical model as defined by equations (1) and (2). We work within the Bayesian framework, so our objective is to calculate the posterior distribution for the parameters of interest, i.e. the probability distribution of those parameters given the observed data. We also want to allow inference on which SNPs affect PCa, which we achieve by allowing some or all of the SNP log-OR values to be exactly zero. We use m to indicate the model, i.e. which SNPs are not zero, and so wish to calculate

| (4) |

where vector

contains all parameters of the hierarchical logistic regression model described for method 1. We introduce β̃m to denote the vector of all SNP log-ORs, some of which may be 0. Note that the likelihood function, P(Data | θ̃, m) is the same as for method 1, i.e. corresponds to a logistic regression of PCa on age, PSA ratio, number of biopsy cores, prostate volume, family history and the markers selected in model m, with random intercepts for country. The prior choice of distribution, P(θ̃, m), across both model space and all parameters is described below.

We cannot calculate (4) analytically and so use Markovchain Monte Carlo, specifically reversible jump Metropolis-Hastings (RJMH) [Green, 1995; Lunn et al., 2006], to sample from the required posterior. The RJMH sampling scheme starts at an initial model, i.e. combination of non-null SNPs and set of parameter values, m(0) and θ̃(0). To sample the next model and set of parameters, m(1)and θ̃(1), we propose moving from the current state to another model and/or set of parameter values, m* and θ̃*, by using a proposal function q (m*, θ̃* | m, θ̃). First, the model is proposed by choosing whether to add a parameter (in our case non-null SNP log-ORs), remove a parameter, swap out one parameter for another or whether to use the same parameters as in the current model (a ‘null’ move). ‘Null’ moves were chosen with probability 1/2, and all other moves with probability 1/6 for which specific parameters to remove, swap or add were randomly selected from those available. When certain moves were impossible, e.g. when the current model is saturated, the remaining probabilities were re-normalised to sum to 1. Second, we propose values for the parameters present in the proposed model. Newly added log-ORs were drawn from normal distributions centred on 0, whereas otherwise parameters were updated by drawing from normal distributions centred on the current value. We then accept the proposed model and parameter values as the next sample with probability equal to the Metropolis-Hastings ratio:

If this new set of values is accepted, the proposed set is accepted as m(1)and θ̃(1); otherwise, the sample value remains equal to the current sample value, i.e. m(1) = m(0)and θ̃(1) = θ̃(0) It can be shown that this produces a sequence of samples that converge to the required posterior distribution [Gilks et al., 1996]. For every Bayesian model fitted, we ran 10 million iterations, using a burn-in of five million iterations. This insured satisfactory convergence of the RJMH sampling scheme, as checked with different seeds and by inspecting plots of parameter values. To make inference on which SNPs associate with PCa in the REDUCE subjects, we simply calculate what proportion of iterations (after convergence) each SNP was present in the selected model, i.e. the posterior probability of association between each SNP and PCa. Since these probabilities should be interpreted in light of the prior (described next), Bayes factors that measure the ratio of posterior to prior odds of association were also calculated for each SNP. Bayes factors are becoming increasingly used in genetic epidemiology as an alternative to P-values [Todd et al., 2007; Wakefield, 2008]. To make subject-specific risk predictions, we first build a sample from each subject’s posterior distribution of risk by calculating their risk for each set of values in the posterior distribution of logistic regression parameters. For the purposes of calibration, ROC and PPV inference, the Bayesian-predicted risk was defined as the mean of each individual’s posterior sample of predicted risk. While not utilised here, it is noted that risk uncertainty intervals may be naturally obtained from the Bayesian model by calculating 95% credible intervals across these posterior samples of subject-specific predicted risk.

Priors

An informative normal prior was placed on each SNP log-OR;

where β̂m and ŝm are the log-OR and standard error estimates from the meta-analysis for SNP m. Since the REDUCE subjects were selected for elevated risk of PCa, and therefore differ from the general populations from which the statistics included in the meta-analyses were drawn, meta-analytic standard errors were inflated by 50% for use in the priors (no inflation would correspond to assuming complete exchangeability between the prior GWAS populations and the REDUCE population). Sensitivity to the priors was checked by investigating the robustness of inference using inflation factors of 1.2 (more weight on the prior) and 2 (less weight). Results were similar, and inference the same (Table S4 in Supplementary Material). Flat N(0,5) priors were used for the intercept and all log-ORs not available for meta-analysis. A Gamma(0.001,0.001) prior was used for the between study precision, which is a standard reference prior [Spiegelhalter and Best, 2003].

We also need to specify a prior on the model space, i.e. how many SNPs are causal, which we do by specifying a prior on n SNPs being included in the model and then assuming that all models with n SNPs are equally likely. This could of course be modified, where certain SNPs – perhaps because of prior evidence of functionality – are judged more likely to be causal than others. While the underlying biological mechanisms are not yet understood for any of the SNPs considered here, since the SNPs in this analysis had been replicated in GWAS in other studies, we judged them all as strong candidates for association with PCa and so allowed a prior probability that 20% of the SNPs had nonzero effects. This was achieved by using a truncated Poisson prior across the model space with mean 0.2 M. That is, the prior probability for each model in which n SNPs have nonzero effects is given by

where

Sensitivity to the model space prior rate of 20% was examined and inference was determined to be robust to the choice of this rate (Table S6 in Supplementary Material).

Posterior Predictive Validation

In addition to 10-fold cross-validation, an alternative fully Bayesian approach was investigated, in which the Bayesian logistic regression was fitted to the entire dataset, and validated using the posterior predictive distribution.

Define the parameter values at iteration k in the posterior sample as and . The posterior predicted risk for individual j at iteration k, , is given by

| (5) |

Evaluating (5) for every iteration k, a posterior sample of predicted risks for individual j is generated. To generate a sample from the posterior predicted distribution of disease for individual j then simply requires drawing from independent Bernoulli distributions centred at each for each iteration k. Parameter uncertainty and sampling variation are therefore reflected over the posterior predictive distribution of disease. Performing this process for every individual j at each iteration k generates a large collection of validation ‘data sets’ (one per saved iteration of the original Markov Clain Monte Carlo [MCMC] run), all of equal size, where the covariates are all identical but the vector of individual disease statuses differs. In principle, this is advantageous to cross-validation since all data is used for model fitting (rather than 90%), and a validation data set is used of equal size to the fitting dataset (rather than 10% of the size).

ROC AUCs were calculated within each of these posterior predictive validation data sets and averaged. Since we have obtained a posterior sample of validation datasets, we were able to calculate 95% credible intervals around the AUC. In particular, we were able to obtain a 95% credible interval for the percent improvement in ROC AUC owing to genetic information allowing a formal test of whether including genetics improves predictive discrimination as measured by the ROC AUC. Delong et al. present a test to compare calibrated ROC AUCs [DeLong et al., 1988], however, this is designed to be used with independent model training and validation data. Furthermore, their method does not formally quantify the difference in AUCs.

Although posterior predictive validation was used to generate credible intervals for the ROC AUCs with and without genetics under method 3,10-fold cross-validation was favoured to generate the calibration, ROC and PPV plots. This is because the posterior predictive simulation model may not capture all sources of variation in the real data, so contrasting predictions against genuinely observed data via cross-validation is likely to be more informative for the purpose of these plots, and enables comparison with methods 1 and 2.

RESULTS

MODEL FIT

For each of the three methods, there was evidence to include prostate volume, and strong evidence to include baseline age, family history and ‘PSA ratio’ as covariates in all models (genetic adjusted ORs with 95% intervals, and P-values for the frequentist models 1 and 2, are shown in Table S3 in Supplementary Material). There was only borderline evidence to include number of biopsy cores, however, given its potential as a confounder, we decided a priori to include this variable in all models regardless of statistical significance.

There was strong evidence that inclusion of genetics variables in addition to the clinical covariates age, family history, number of biopsy cores, prostate volume, PSA ratio and drug in each of the three methods improved the model fits to these data. A likelihood-ratio test comparing method 1, with and without terms, for the 33 SNPs gave a P-value = 0.0012. Similarly, a likelihood-ratio test to assess the inclusion of the genetic score variable in method 2 gave a P-value of 1.12 × 10−5. Univariate SNP associations among the REDUCE subjects are provided in Table S4 in Supplementary Material. For method 3, the posterior probability for inclusion of one or more SNPs was estimated as 1, since at least one SNP was always selected in the model by the reversible jump algorithm. SNP-specific posterior probabilities of association with PCa may be found in Table S5 in Supplementary Material. Compared to a prior probability set at 0.2, this (as expected) provides very strong evidence for genetic associations with PCa.

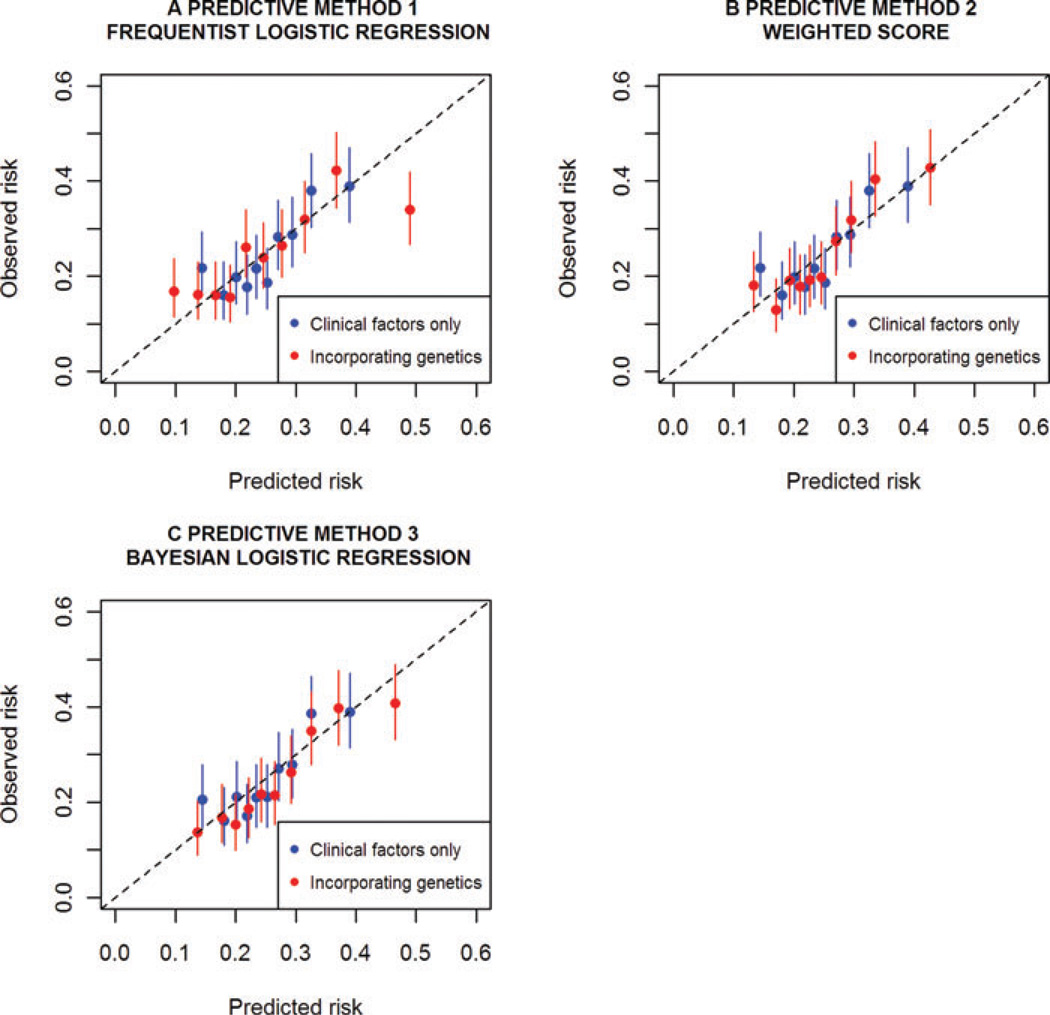

CALIBRATION

Cross-validated calibration plots for all three predictive methods are presented in Figure 1. For each decile of predicted risk, these plots compare the average predicted and observed risks across the cross-validation folds. The average 95% confidence intervals for observed risk are also shown. The data displayed in these plots may be found in Table S7 in Supplementary Material. Calibration was best for method 3 when genetic information was incorporated – this was the only predictive model for which the average predicted risk fell in the observed risk confidence interval for all deciles. Models fitted under methods 1 and 2 appeared poorly calibrated for the lowest risk decile and, for method 1, the highest risk decile. In addition to producing the best-calibrated model, method 3 demonstrated the most improvement in calibration upon inclusion of genetic information, followed by method 1. Both these frameworks model distinct terms for each SNP thereby allowing REDUCE data to influence the weights. Therefore, calibration improvement appeared more sensitive to adapting the relative SNP weights to the REDUCE data, than to inclusion of additional external genetic information.

Fig. 1.

Predicted risk vs. observed risk for each predictive method with and without genetic information. These are calculated within deciles of predicted risk. Models were fitted and assessed under 10-fold cross-validation. Average 95% confidence intervals in the observed cross-validated risk are displayed. Clinical factors, included in every model, were family history, baseline age, PSA ratio, prostate volume and number of biopsy cores.

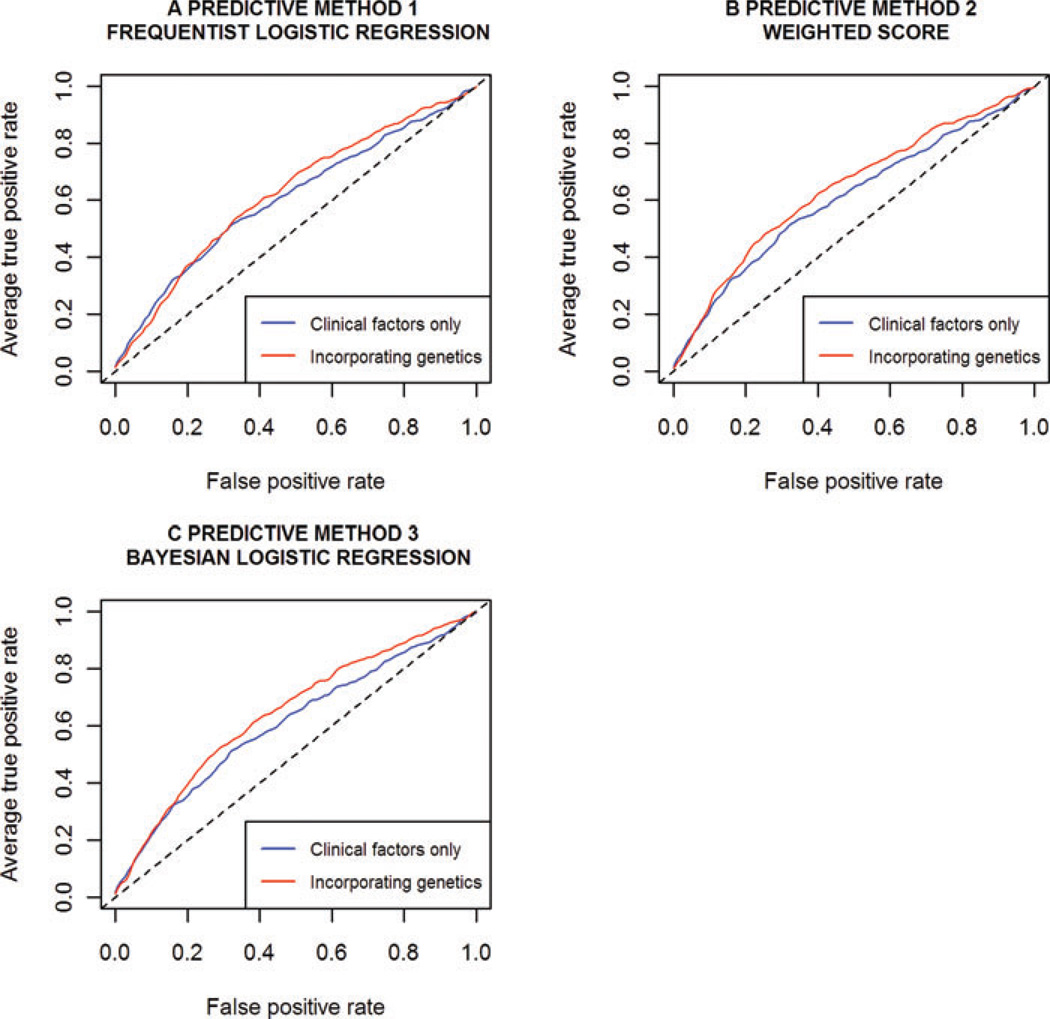

ROC ANALYSIS

Cross-validated ROC curves for each method, with and without the genetic information, are shown in Figure 2, and corresponding AUC estimates are given in Table II. As explained in the methods, 10-fold cross-validation was used to generate more informative ROC plots for method 3, and to enable comparison with methods 1 and 2. By also cross-validating method 3, we were able to investigate whether the assumptions underlying the posterior predictive validation simulations were leading to over-estimates of ROC AUCs, by comparing against the AUC estimates obtained from the cross-validation. Encouragingly, point estimates were identical to two decimal places.

Fig. 2.

ROC analysis of each predictive method with and without genetic information. Models were fitted and assessed under 10-fold cross-validation. Clinical factors, included in every model, were family history, baseline age, PSA ratio, prostate volume and number of biopsy cores.

TABLE II.

ROC area under the curve estimates

| Frequentist models | Ten-fold cross-validated AUC ± standard error |

|---|---|

| Age, family history, PSA ratio, prostate volume, no. cores | 0.61 ± 0.05 |

| Age, family history, PSA ratio, prostate volume, no. cores, 33 SNPs | 0.62 ± 0.06 |

| Age, family history, PSA ratio, prostate volume, no. cores, weighted score | 0.64 ± 0.05 |

| Bayesian models | Posterior predictive validated AUC (95% credible interval) |

| Age, family history, PSA ratio, prostate volume, no. cores (A) | 0.61 (0.56, 0.65) |

| Age, family history, PSA ratio, prostate volume, no. cores, 33 SNPs (B) | 0.64 (0.60, 0.68) |

| AUC improvement upon inclusion of genetic information (B vs. A) | 5.6% (0.7%, 10.6%)a |

AUC standard errors for the frequentist models were estimated as the standard deviation in the AUC across the cross-validation folds.

Percentage of AUC increase – exclusion of 0% from the interval indicates statistical significance

All methods produced identical AUCs to two decimal places of 0.61 (method 3: 95% CrI: [0.56, 0.65]) when the genetic variables were not included. The addition of the genetic variables resulted in a modest improvement in AUC for all three methods. This improvement was largest, and notably equivalent, for the two methods that utilise the external meta-analysis estimates (methods 2 and 3), with the AUC increasing from 0.61 to 0.64 (method 3: 95% CrI: [0.60, 0.68]).

As explained in the methods, using posterior predictive validation for method 3 allowed inference of a 95% credible interval for the genetic AUC improvement. A median improvement of 5.6% was estimated with a 95% credible interval of (0.7%, 10.6%). Note that this interval excludes 0%.

While inclusion of genetics led to an overall improvement in AUC, it did not provide superior predictive performance across the entire range of possible predicted risk cut-offs. In particular, for low false-positive rates, i.e. for high predicted risk cut-offs, inclusion of genetic information led to worse performance. Note however, that such high cut-offs result in very low sensitivity for all methods.

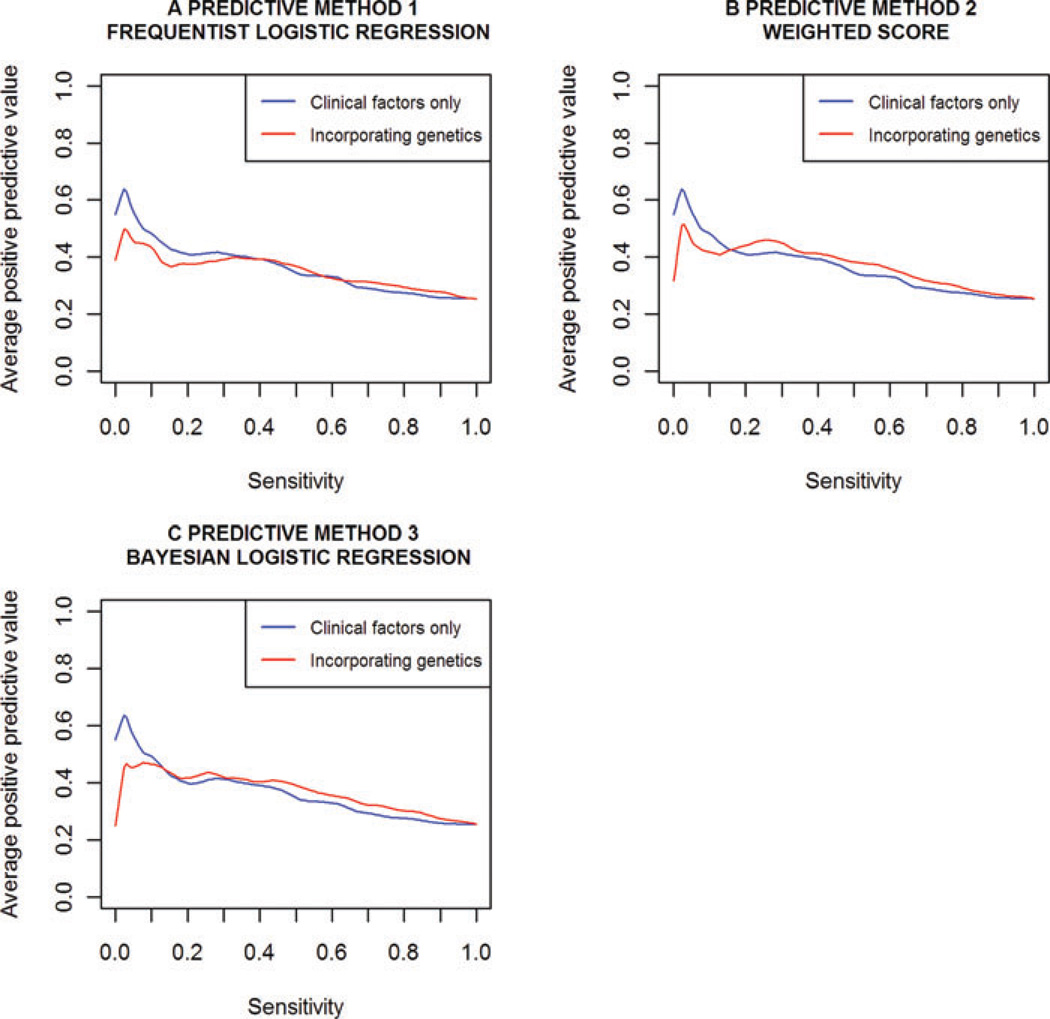

POSITIVE PREDICTIVE VALUE (PPV)

Plots of the cross-validated PPV vs. sensitivity, with and without genetic information, for all three methods are provided in Figure 3. These plots suggest inclusion of genetic information only results in small increases in PPV. As found with the ROC curves, predictive improvement upon inclusion of genetic information was best for methods 2 and 3, which incorporate the external meta-analysis data. Arguably, method 3 performed slightly better than method 2, resulting in marginally higher PPV for sensitivity estimates above 0.40. The range of cut-offs for which method 2 performed better corresponded to low-sensitivity estimates below 0.40. Consistent with the ROC curves, for the highest cut-offs (far left of these plots), the scores were superior without genetic information. However it is reminded that the range of cut-offs for which this occurs results in very low sensitivity.

Fig. 3.

PPV vs. sensitivity for each predictive method with and without genetic information. Models were fitted and assessed under 10-fold cross-validation. Clinical factors, included in every model, were family history, baseline age, PSA ratio, prostate volume and number of biopsy cores.

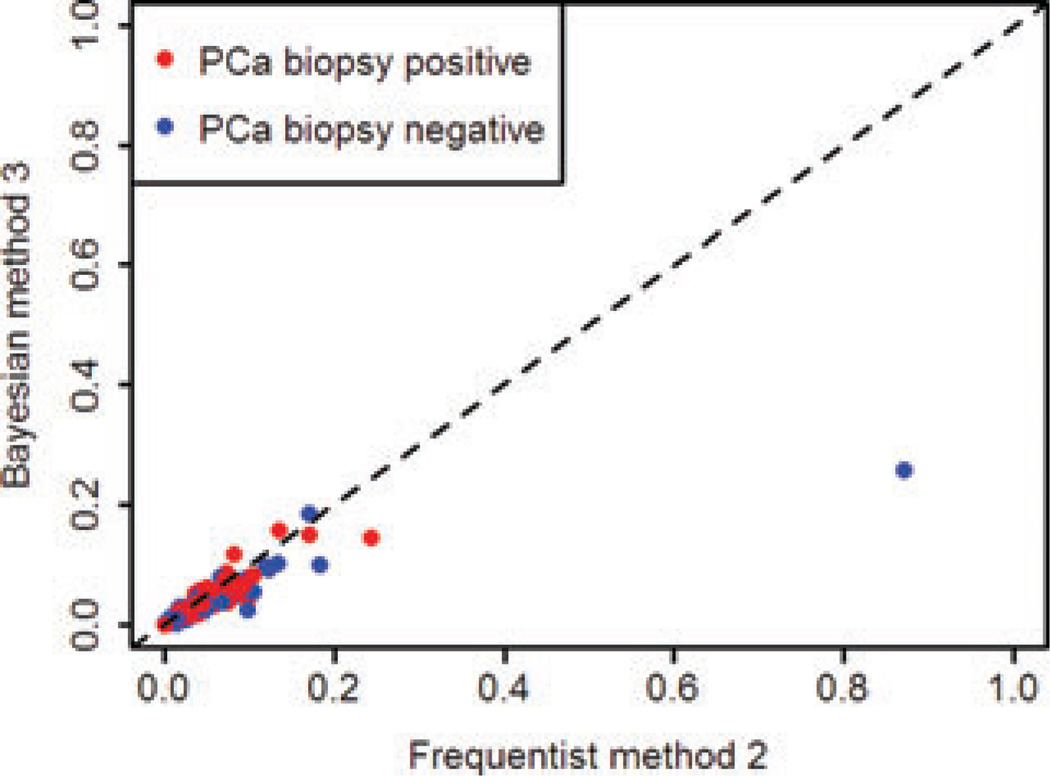

CORRELATION BETWEEN THE THREE METHODS

Correlation between the two best-performing methods, methods 2 and 3, which both incorporate external information but via mechanisms of different complexity, was investigated by plotting the predicted risk from each [Figure 4]. The two methods showed good, but not complete agreement [r2 = 0.868, 95% CI (0.856, 0.880)]. This indicates that while both methods incorporate the external meta-analysis information, the different mechanisms by which they do so lead to somewhat different subject specific risk predictions. This is consistent with the ROC and PPV plots; despite resulting in near-identical AUC estimates, the ROC curves and PPV curves for these methods had slightly different shapes, indicating subtle differences in predictive performance at various cut-offs. There were a few outlying subjects with negative biopsies that had higher (and therefore poorer) disease risks estimated by method 2 – this is consistent with a marginally better PPV for method 3 than found for method 2 across a range of cut-offs. Correlation in predicted probabilities was strongest between methods 1 and 3 [r2 = 0.973, 95% CI (0.970, 0.975)], which is likely because they are both based on the same linear predictor (separate terms for each variant).

Fig. 4.

Calibration between predicted risk from the frequentist method 2 and the Bayesian method 3, both of which incorporated external information.

BETWEEN REGION HETEROGENEITY

While adjusting for PSA ratio, the median and 95% CrI for the between region variability parameter, , from the Bayesian analysis were 0.20 and (0.06, 0.55), respectively, indicating heterogeneity in baseline prevalence between countries, and thus the possibility of some degree of variability by region. In light of the evidence for between-region heterogeneity, it was investigated whether accounting for region would improve prediction. A benefit of the Bayesian approach is that the region-specific intercepts are naturally estimated as part of the MCMC, and so may be used for prediction (so far, the linear predictor for score 3 has just used the global intercept for prediction). Upon accounting for random intercepts in prediction, the AUCs, calibration, ROC and PPV plots for method 3 showed negligible improvement (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

This work represents the most comprehensive assessment to date of the predictive utility of genetic markers over existing clinical parameters for PCa. We were able to demonstrate that the addition of genetic information to the clinical variables age, family history and PSA ratio lead to a non-zero, though relatively small improvement in prediction of PCa. Modest improvements from inclusion of genetic information were observed according to three diagnostics considered (ROC curves, calibration and PPV plots) over use of the clinical variables alone. Marginal predictive improvements of genetics have also been observed for breast cancer [Wacholder et al., 2010] and type 2 diabetes [Meigs et al., 2008].

Although incorporation of genetics into a combined genetic and clinical score appears to only marginally improve prediction of PCa over the common clinical parameters in current use, a detailed comparison of different techniques for construction of such a score is presented which may have relevance to other diseases. The principal value of this comparison is likely to lie in observations on performance similarities, rather than differences, between three approaches of substantially different resource requirements. For instance, the two methods that incorporated external meta-analysis estimates for the effects of the SNPs on PCa – one via a weighted score and the other via informative priors in a Bayesian model – demonstrated the most predictive improvement, but the magnitude of that improvement is perhaps disappointing given the effort that was required to curate this information. It is also of note how similar these two methods were in performance, since the Bayesian approach requires significantly more time and expertise to implement than the weighted score. Whereas the weighted score combines the meta-analysis estimates into a single covariate (thereby fixing the relative contribution to disease of each SNP), the Bayesian model fits distinct terms for each SNP allowing their contributions to be tuned to the current data. Therefore, the negligible difference observed in predictive performance between these approaches suggests a lack of sensitivity to whether or not the weights are fine-tuned to the REDUCE subjects. This is likely due to two reasons. First, the genetic effects used in the meta-analysis were generally small and therefore relatively homogeneous in their contribution to disease risk and, second, this observation suggests that the relative weights estimated from previous studies are reasonably comparable to the REDUCE subjects, despite the difference in populations from which subjects are drawn, meaning little is gained from further tuning. The similar performance between the weighted score and Bayesian modelling approaches to incorporating external information should encourage similar comparison for other prediction problems, at least where there is relatively little variation in effect size among the genetic variants included in the model.

While all three predictive models were found to have similar predictive performance, it is important to distinguish advantages we have demonstrated from using a Bayesian model assessment framework, from the predictive performance of the Bayesian model itself. Use of Bayesian posterior predictive validation offered an elegant way to formally infer a 95% credible interval for the discriminatory improvement (measured here as the ROC AUC increase) from incorporation of genetics. Furthermore, AUC 95% credible intervals were easy to construct by summarising across the different posterior predictive simulation draws. Construction of confidence intervals from the cross-validated AUC standard error estimates was avoided, since the distributional properties of the AUC are not well understood. Although we only present posterior predictive validated results for the Bayesian model, this technique could theoretically also be used to assess Bayesian approximations of any frequentist model, by using uninformative priors on model parameters and thus the corresponding posterior predictive simulation model. We calculated posterior predictive validated AUCs for all methods. Inference was very similar, with the Bayesian method 3 genetic ROC AUC (shown) coming out as the highest value.

While the posterior predictive distribution allows useful inference, caution should generally be applied when using simulations to assess predictive performance. Despite the fact parameter uncertainty, and uncertainty in the terms of the linear regression model, are reflected in the posterior predictive distribution, other uncertainty in the data-generating model (e.g. the use of a linear model with logistic link function) is not. It is therefore unlikely that the simulation model will be capable of reflecting all sources of variation present in a particular type of data. Ntzoufras suggests that use of the posterior predictive distribution for model checking is questionable for its double use of the data [Ntzoufras, 2009, pp 342–344], and highlights cross-validatory predictive densities as an alternative, in which separate data are used for model fitting and generation of the posterior predictive. While this technique was not explored here, we did focus on cross-validated (rather than posterior predictive validated) calibration, ROC and PPV plots for method 3, since we judged them more informative. We also recommend where possible that posterior predictive validated estimates are checked against those from cross-validation. Though in our case this demonstrated virtually identical AUC point estimates, it is known that posterior predictive model assessment is in general conservative [Bayarri and Berger, 2000; Gelman et al., 1996]. Marshall and Spiegelhalter present an ingenious approach for attenuating the influence of a data point yi on its replicate , by replicating both random effects and data during the posterior predictive sampling process. Unfortunately however, since our model only incorporates random intercepts, and not random effects, this approach offers little advantage for our problem.

A number of factors limiting the generalisability of our results should be noted. First, conclusions on predictive benefit should not be drawn according to improvement in the ROC AUC alone. This is an average performance measure across all possible risk cut-offs, many of which are either too stringent or too inclusive to be of practical value, and furthermore, the ROC only reflects true- and false-positive rates. While we have also looked at calibration and PPV in an attempt to broaden the utility of our work, for some contexts estimation of additional predictive performance measures may be necessary to draw conclusions on the benefit of genetics. Second, the external studies used to generate the meta-analytic estimates have not all adjusted for the same clinical covariates that we do in our analysis. If any of the SNPs act on PCa via clinical factors, then their adjusted and unadjusted associations will differ. As noted above, we were able to investigate sensitivity to the assumption of exchangeability between the meta-analysis estimates, and the parameters estimated in REDUCE as part of the Bayesian method 3 by relaxing the informative priors. Finally, generalisability of our results (and indeed, applicability of the external data) is further complicated by the fact REDUCE subjects were selected for elevated PSA. Since PSA is a risk factor for PCa, associations between all risk factors and PCa in the REDUCE data will have some degree of bias towards the null (it is a harder to problem to differentiate risk among a high risk population). However, since all risk factors would be biased towards the null, it is not clear how much this would impact our estimates of the relative improvement of genetics.

Although progress is being made in risk prediction for complex diseases with both genetic and environmental risk factors, challenges remain. Work is still in progress to effectively model and evaluate less understood sources of genetic variability such as copy number and rare genetic variants. As the price of technologies required to measure such data continues to decrease, these factors may become candidates for clinical prediction. Prediction methodologies will therefore continually evolve to accommodate these new types of data, and as such, a number of alternative approaches will be available in any setting. We provide a detailed comparison of three approaches that have broad applicability, but would require different resource commitments to implement. Our observations on performance similarities could be valuable and may have relevance to a wide range of gene-disease associations. We also present the most comprehensive assessment to date of the predictive performance of genetic markers for PCa over existing clinical parameters in which a statistically significant, though marginal, improvement was found.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the patients enrolled in REDUCE who provided consent and genetic samples that enabled this study, and the clinicians who contributed their expertise in recruiting study patients for the REDUCE clinical study. Dave Pulford, Jennifer Aponte, Jon Charnecki and Mary Ellyn Volk participated in consent reconciliation and sample management to enable genetic sample selection for inclusion and genotype determination. Karen King provided data management support for this project. We thank Silviu-Alin Bacanu and Matt Nelson for multiple discussions on power determination, method limitations and results. We appreciated the assistance of Lauren Marmor in coordinating the support of the Avodart Collaborative Research Team.

This work was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health (CA140262 and RC2 CA148463 to J.X.).

Footnotes

Supporting Information is available in the online issue at wileyonlinelibrary.com.

REFERENCES

- Amundadottir LT, Sulem P, Gudmundsson J, Helgason A, Baker A, Agnarsson BA, Sigurdsson A, Benediktsdottir KR, Cazier J-B, Sainz J, Jakobsdottir M, Kostic J, Magnusdottir DN, Ghosh S, Agnarsson K, Birgisdottir B, Le Roux L, Olafsdottir A, Blondal T, Andresdottir M, Gretarsdottir OS, Bergthorsson JT, Gudbjartsson D, Gylfason A, Thorleifsson G, Manolescu A, Kristjansson K, Geirsson G, Isaksson H, Douglas J, Johansson J-E, Bäiter K, Wiklund F, Montie JE, Yu X, Suarez BK, Ober C, Cooney KA, Gronberg H, Catalona WJ, Einarsson GV, Barkardottir RB, Gulcher JR, Kong A, Thorsteinsdottir U, Stefansson K. A common variant associated with prostate cancer in European and African populations. Nat Genet. 2006;38:652–658. doi: 10.1038/ng1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andriole GL, Bostwick DG, Brawley OW, Gomella LG, Marberger M, Montorsi F, Pettaway CA, Tammela TL, Teloken C, Tindall DJ, Somerville MC, Wilson TH, Fowler IL, Rittmaster RS the REDUCE Study Group. Effect of Dutasteride on the risk of prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1192–1202. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayarri MJ, Berger JO. P values for composite null models. J Am Stat Assoc. 2000;95:1127–1142. [Google Scholar]

- DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:837–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggan D, Zheng SL, Knowlton M, Benitez D, Dimitrov L, Wiklund F, Robbins C, Isaacs SD, Cheng Y, Li G, Sun J, Chang B-L, Marovich L, Wiley KE, Bäter K, Stattin P, Adami H-O, Gielzak M, Yan G, Sauvageot J, Liu W, Kim JW, Bleecker ER, Meyers DA, Trock BJ, Partin AW, Walsh PC, Isaacs WB, Grönberg H, Xu J, Carpten JD. Two genome-wide association studies of aggressive prostate cancer implicate putative prostate tumor suppressor gene DAB2IP. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1836–1844. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easton DF, Eeles RA. Genome-wide association studies in cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:R109–R115. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eeles RA, Kote-Jarai Z, Al Olama AA, Giles GG, Guy M, Severi G, Muir K, Hopper JL, Henderson BE, Haiman CA, Schleutker J, Hamdy FC, Neal DE, Donovan JL, Stanford JL, Ostrander EA, Ingles SA, John EM, Thibodeau SN, Schaid D, Park JY, Spurdle A, Clements J, Dickinson JL, Maier C, Vogel W, Dork T, Rebbeck TR, Cooney KA, Cannon-Albright L, Chappuis PO, Hutter P, Zeegers M, Kaneva R, Zhang H-W, Lu Y-J, Foulkes WD, English DR, Leongamornlert DA, Tymrakiewicz M, Morrison J, Ardern-Jones AT, Hall AL, O’Brien LT, Wilkinson RA, Saunders EJ, Page EC, Sawyer EJ, Edwards SM, Dearnaley DP, Horwich A, Huddart RA, Khoo VS, Parker CC, Van As N, Woodhouse CJ, Thompson A, Christmas T, Ogden C, Cooper CS, Southey MC, Lophatananon A, Liu J-F, Kolonel LN, Le Marchand L, Wahlfors T, Tammela TL, Auvinen A, Lewis SJ, Cox A, FitzGerald LM, Koopmeiners JS, Karyadi DM, Kwon EM, Stern MC, Corral R, Joshi AD, Shahabi A, McDonnell SK, Sellers TA, Pow-Sang J, Chambers S, Aitken J, Gardiner RA, (Frank), Batra J, Kedda MA, Lose F, Polanowski A, Patterson B, Serth J, Meyer A, Luedeke M, Stefflova K, Ray AM, Lange EM, Farnham J, Khan H, Slavov C, et al. Identification of seven new prostate cancer susceptibility loci through a genome-wide association study. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1116–1121. doi: 10.1038/ng.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eeles RA, Kote-Jarai Z, Giles GG, Olama AAA, Guy M, Jugurnauth SK, Mulholland S, Leongamornlert DA, Edwards SM, Morrison J, Field HI, Southey MC, Severi G, Donovan JL, Hamdy FC, Dearnaley DP, Muir KR, Smith C, Bagnato M, Ardern-Jones AT, Hall AL, O’Brien LT, Gehr-Swain BN, Wilkinson RA, Cox A, Lewis S, Brown PM, Jhavar SG, Tymrakiewicz M, Lophatananon A, Bryant SL, Horwich A, Huddart RA, Khoo VS, Parker CC, Woodhouse CJ, Thompson A, Christmas T, Ogden C, Fisher C, Jamieson C, Cooper CS, English DR, Hopper JL, Neal DE, Easton DF. Multiple newly identified loci associated with prostate cancer susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2008;40:316–321. doi: 10.1038/ng.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FitzGerald LM, Kwon EM, Koopmeiners JS, Salinas CA, Stanford JL, Ostrander EA. Analysis of recently identified prostate cancer susceptibility loci in a population-based study: associations with family history and clinical features. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3231–3237. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman A, Meng XL, Stern H. Posterior predictive assessment of model fitness via realized discrepancies. Stat Sin. 1996;6:733–759. [Google Scholar]

- Gilks WR, Richardson S, Spiegelhalter DJ. Markov Chain Monte Carlo In Practice. 2nd Edition. London: Chapman & Hall CRC Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gion M, Mione R, Barioli P, Barichello M, Zattoni F, Prayer-Galetti T, Plebani M, Aimo G, Terrone C, Manferrari F, Madeddu G, Caberlotto L, Fandella A, Pianon C, Vianello L. Percent free prostate-specific antigen in assessing the probability of prostate cancer under optimal analytical conditions. Clin Chem. 1998;44:2462–2470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green PJ. Reversible jump Markov chain Monte Carlo computation and Bayesian model determination. Biometrika. 1995;82:711. [Google Scholar]

- Gudmundsson J, Sulem P, Manolescu A, Amundadottir LT, Gudbjartsson D, Helgason A, Rafnar T, Bergthorsson JT, Agnarsson BA, Baker A, Sigurdsson A, Benediktsdottir KR, Jakobsdottir M, Xu J, Blondal T, Kostic J, Sun J, Ghosh S, Stacey SN, Mouy M, Saemundsdottir J, Backman VM, Kristjansson K, Tres A, Partin AW, Albers-Akkers MT, Godino-Ivan Marcos J, Walsh PC, Swinkels DW, Navarrete S, Isaacs SD, Aben KK, Graif T, Cashy J, Ruiz-Echarri M, Wiley KE, Suarez BK, Witjes JA, Frigge M, Ober C, Jonsson E, Einarsson GV, Mayordomo JI, Kiemeney LA, Isaacs WB, Catalona WJ, Barkardottir RB, Gulcher JR, Thorsteinsdottir U, Kong A, Stefansson K. Genome-wide association study identifies a second prostate cancer susceptibility variant at 8q24. Nat Genet. 2007a;39:631–637. doi: 10.1038/ng1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudmundsson J, Sulem P, Steinthorsdottir V, Bergthorsson JT, Thorleifsson G, Manolescu A, Rafnar T, Gudbjartsson D, Agnarsson BA, Baker A, Sigurdsson A, Benediktsdottir KR, Jakobsdottir M, Blondal T, Stacey SN, Helgason A, Gunnarsdottir S, Olafsdottir A, Kristinsson KT, Birgisdottir B, Ghosh S, Thorlacius S, Magnusdottir D, Stefansdottir G, Kristjansson K, Bagger Y, Wilensky RL, Reilly MP, Morris AD, Kimber CH, Adeyemo A, Chen Y, Zhou J, So W-Y, Tong PCY, Ng MCY, Hansen T, Andersen G, Borch-Johnsen K, Jorgensen T, Tres A, Fuertes F, Ruiz-Echarri M, Asin L, Saez B, van Boven E, Klaver S, Swinkels DW, Aben KK, Graif T, Cashy J, Suarez BK, van Vierssen Trip O, Frigge ML, Ober C, Hofker MH, Wijmenga C, Christiansen C, Rader DJ, Palmer CNA, Rotimi C, Chan JCN, Pedersen O, Sigurdsson G, Benediktsson R, Jonsson E, Einarsson GV, Mayordomo JI, Catalona WJ, Kiemeney LA, Barkardottir RB, Gulcher JR, Thorsteinsdottir U, Kong A, Stefansson K. Two variants on chromosome 17 confer prostate cancer risk, and the one in TCF2 protects against type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2007b;39:977–983. doi: 10.1038/ng2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez DJ, Han M, Humphreys EB, Mangold LA, Taneja SS, Childs SJ, Bartsch G, Partin AW. Predicting the outcome of prostate biopsy: comparison of a novel logistic regression-based model, the prostate cancer risk calculator, and prostate-specific antigen level alone. BJU International. 2009;103:609–614. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.08127.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu F-C, Sun J, Zhu Y, Kim S-T, Jin T, Zhang Z, Wiklund F, Kader AK, Zheng SL, Isaacs W, Grönberg H, Xu J. Comparison of two methods for estimating absolute risk of prostate cancer based on single nucleotide polymorphisms and family history. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1083–1088. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-1176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsdottir J, Gorin MB, Conley YP, Ferrell RE, Weeks DE. Interpretation of genetic association studies: markers with replicated highly significant odds ratios may be poor classifiers. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000337. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S-T, Cheng Y, Hsu F-C, Jin T, Kader AK, Zheng SL, Isaacs WB, Xu J, Sun J. Prostate cancer risk-associated variants reported from genome-wide association studies: meta-analysis and their contribution to genetic Variation. Prostate. 2010;70:1729–1738. doi: 10.1002/pros.21208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lango H, Palmer CNA, Morris AD, Zeggini E, Hattersley AT, McCarthy MI, Frayling TM, Weedon MN. Assessing the combined impact of 18 common genetic variants of modest effect sizes on type 2 diabetes risk. Diabetes. 2008;57:3129–3135. doi: 10.2337/db08-0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X, Song K, Lim N, Yuan X, Johnson T, Abderrahmani A, Vollen-weider P, Stirnadel H, Sundseth S, Lai E, Burns D, Middleton L, Roses A, Matthews P, Waeber G, Cardon L, Waterworth D, Mooser V. Risk prediction of prevalent diabetes in a Swiss population using a weighted genetic score—the CoLaus study. Diabetologia. 2009;52:600–608. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1254-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunn DJ, Whittaker JC, Best N. A Bayesian toolkit for genetic association studies. Genet Epidemiol. 2006;30:231–247. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meigs JB, Shrader P, Sullivan LM, McAteer JB, Fox CS, Dupuis J, Manning AK, Florez JC, Wilson PWF, D’Agostino RB, Cupples LA. Genotype score in addition to common risk factors for prediction of type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2208–2219. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen CT, Yu C, Moussa A, Kattan MW, Jones JS. Performance of prostate cancer prevention trial risk calculator in a contemporary cohort screened for prostate cancer and diagnosed by extended prostate biopsy. J Urol. 2010;183:529–533. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ntzoufras I. Bayesian Modeling Using WinBUGS. John Wiley and Sons; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Optenberg SA, Clark JY, Brawer MK, Thompson IM, Stein CR, Friedrichs P. Development of a decision-making tool to predict risk of prostate cancer: the Cancer of the Prostate Risk Index (CAPRI) test. Urology. 1997;50:665–672. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00451-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paynter NP, Chasman DI, Pare G, Buring JE, Cook NR, Miletich JP, Ridker PM. Association between a literature-based genetic risk score and cardiovascular events in women. JAMA. 2010;303:631–637. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salinas CA, Koopmeiners JS, Kwon EM, FitzGerald L, Lin DW, Ostrander EA, Feng Z, Stanford JL. Clinical utility of five genetic variants for predicting prostate cancer risk and mortality. Prostate. 2009;69:363–372. doi: 10.1002/pros.20887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, Tammela TLJ, Ciatto S, Nelen V, Kwiatkowski M, Lujan M, Lilja H, Zappa M, Denis LJ, Recker F, Berenguer A, Maattanen L, Bangma CH, Aus G, Villers A, Rebillard X, van der Kwast T, Blijenberg BG, Moss SM, de Koning HJ, Auvinen A, the ERSPCInvestigators. Screening and prostate-cancer mortality in a randomized European study. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1320–1328. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serfling R, Shulman M, Thompson GL, Xiao Z, Benaim E, Roehrborn CG, Rittmaster R. Quantifying the impact of prostate volumes, number of biopsy cores and 5alpha-reductase inhibitor therapy on the probability of prostate cancer detection using mathematical modeling. J Urol. 2007;177:2352–2356. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegelhalter DJ, Best NG. Bayesian approaches to multiple sources of evidence and uncertainty in complex cost-effectiveness modelling. Stat Med. 2003;22:3687–3709. doi: 10.1002/sim.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas G, Jacobs KB, Yeager M, Kraft P, Wacholder S, Orr N, Yu K, Chatterjee N, Welch R, Hutchinson A, Crenshaw A, Cancel-Tassin G, Staats BJ, Wang Z, Gonzalez-Bosquet J, Fang J, Deng X, Berndt SI, Calle EE, Feigelson HS, Thun MJ, Rodriguez C, Albanes D, Virtamo J, Weinstein S, Schumacher FR, Giovannucci E, Willett WC, Cussenot O, Valeri A, Andriole GL, Crawford ED, Tucker M, Gerhard DS, Fraumeni JF, Hoover R, Hayes RB, Hunter DJ, Chanock SJ. Multiple loci identified in a genome-wide association study of prostate cancer. Nat Genet. 2008;40:310–315. doi: 10.1038/ng.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson IM, Ankerst DP, Chi C, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, Lucia MS, Feng Z, Parnes HL, Coltman CA. Assessing prostate cancer risk: results from the Prostate Cancer Prevention trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:529–534. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson IM, Pauler Ankerst D, Chi C, Goodman PJ, Tangen CM, Lippman SM, Lucia MS, Parnes HL, Coltman CA. Prediction of prostate cancer for patients receiving Finasteride: results from the Prostate Cancer Prevention trial. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3076–3081. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.6836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson IM, Tangen CM, Ankerst DP, Chi C, Lucia MS, Goodman P, Parnes H, Coltman CA., Jr. The performance of prostate specific antigen for predicting prostate cancer is maintained after a prior negative prostate biopsy. J Urol. 2008;180:544–547. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd JA, Walker NM, Cooper JD, Smyth DJ, Downes K, Plagnol V, Bailey R, Nejentsev S, Field SF, Payne F, Lowe CE, Szeszko JS, Hafler JP, Zeitels L, Yang JHM, Vella A, Nutland S, Stevens HE, Schuilenburg H, Coleman G, Maisuria M, Meadows W, Smink LJ, Healy B, Burren OS, Lam AAC, Ovington NR, Allen J, Adlem E, Leung H-T, Wallace C, Howson JMM, Guja C, Ionescu-Tîrgovişte C, Simmonds MJ, Heward JM, Gough SCL, Dunger DB, Wicker LS, Clayton DG. Robust associations of four new chromosome regions from genome-wide analyses of type 1 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2007;39:857–864. doi: 10.1038/ng2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlaeminck-Guillem V, Ruffion A, Andre J, Devonec M, Paparel P. Urinary prostate cancer 3 test: toward the age of reason? Urology. 2010;75:447–453. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wacholder S, Hartge P, Prentice R, Garcia-Closas M, Feigelson HS, Diver WR, Thun MJ, Cox DG, Hankinson SE, Kraft P, Rosner B, Berg CD, Brinton LA, Lissowska J, Sherman ME, Chlebowski R, Kooperberg C, Jackson RD, Buckman DW, Hui P, Pfeiffer R, Jacobs KB, Thomas GD, Hoover RN, Gail MH, Chanock SJ, Hunter DJ. Performance of common genetic variants in breast-cancer risk models. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:986–993. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0907727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield J. Bayes factors for genome-wide association studies: comparison with P-values. Genet Epidemiol. 2008;33:79–86. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Sun J, Kader AK, Lindströom S, Wiklund F, Hsu F-C, Johansson J-E, Zheng SL, Thomas G, Hayes RB, Kraft P, Hunter DJ, Chanock SJ, Isaacs WB, Grönberg H. Estimation of absolute risk for prostate cancer using genetic markers and family history. Prostate. 2009;69:1565–1572. doi: 10.1002/pros.21002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeager M, Chatterjee N, Ciampa J, Jacobs KB, Gonzalez-Bosquet J, Hayes RB, Kraft P, Wacholder S, Orr N, Berndt S, Yu K, Hutchinson A, Wang Z, Amundadottir L, Feigelson HS, Thun MJ, Diver WR, Albanes D, Virtamo J, Weinstein S, Schumacher FR, Cancel-Tassin G, Cussenot O, Valeri A, Andriole GL, Crawford ED, Haiman CA, Henderson B, Kolonel L, Le Marchand L, Siddiq A, Riboli E, Key TJ, Kaaks R, Isaacs W, Isaacs S, Wiley KE, Gronberg H, Wiklund F, Stattin P, Xu J, Zheng SL, Sun J, Vatten LJ, Hveem K, Kumle M, Tucker M, Gerhard DS, Hoover RN, Fraumeni JF, Hunter DJ, Thomas G, Chanock SJ. Identification of a new prostate cancer susceptibility locus on chromosome 8q24. Nat Genet. 2009;41:1055–1057. doi: 10.1038/ng.444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeager M, Orr N, Hayes RB, Jacobs KB, Kraft P, Wacholder S, Minichiello MJ, Fearnhead P, Yu K, Chatterjee N, Wang Z, Welch R, Staats BJ, Calle EE, Feigelson HS, Thun MJ, Rodriguez C, Albanes D, Virtamo J, Weinstein S, Schumacher FR, Giovannucci E, Willett WC, Cancel-Tassin G, Cussenot O, Valeri A, Andriole GL, Gelmann EP, Tucker M, Gerhard DS, Fraumeni JF, Hoover R, Hunter DJ, Chanock SJ, Thomas G. Genome-wide association study of prostate cancer identifies a second risk locus at 8q24. Nat Genet. 2007;39:645–649. doi: 10.1038/ng2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng SL, Sun J, Wiklund F, Smith S, Stattin P, Li G, Adami H-O, Hsu F-C, Zhu Y, Bäiter K, Kader AK, Turner AR, Liu W, Bleecker ER, Meyers DA, Duggan D, Carpten JD, Chang B-L, Isaacs WB, Xu J, Gronberg H. Cumulative association of five genetic variants with prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:910–919. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa075819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.