Abstract

Radical surgery is the standard of care for fit stage I non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients. Adjuvant treatment should be offered only as part of an investigation trial. Stage II and IIIA adjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy remains the gold standard for completely resected NSCLC tumors. Additionally radiotherapy should be offered in patients with N2 lymph nodes. In advanced stage IIIB/IV or inoperable NSCLC pts, a multidisciplinary treatment should be offered consisted of 4 cycles of cisplatin-based chemotherapy plus a 3rd generation cytotoxic agent or a cytostatic (anti-EGFR, anti-VEGFR) drug.

KEY WORDS : Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), lung cancer, treatment, targeted treatment

Introduction

Lung Cancer was the most common cause of death from cancer with more than 1.38 million deaths worldwide (1).

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for the 80% of all lung cancers. Its main types are: adenocarcinoma (including BAC) 32-40%, squamous 25-30%, large cell 8-16%.

Till lately there were obscure guidelines for the management of NSCLC. Now there is a global attempt to tailor the management of the cancer according to the specific patient’s characteristics, such as the extent of the disease and a number of prognostic and predictive factors.

The IASLC staging project (2) have shown statistical superiority on patient survival in early pathological stage and with median Overall Survival 95 mos for stage IA, 75 mos for stage IB, 44 mos for IIA, 29 mos for IIB and 19 mos for IIIA. Nevertheless a significant influence factor in OS was the subtype of tumor cells (83 mos for Bronchoalveolar carcinoma, BAC, 45 mos for Adenocarcinoma, ADCA, 44 mos for Squamous, SQUAM, 34 mos for Large cell carcinoma, LARGE and 26 mos for Adenosquamous, ADSQ) (Figure 1).

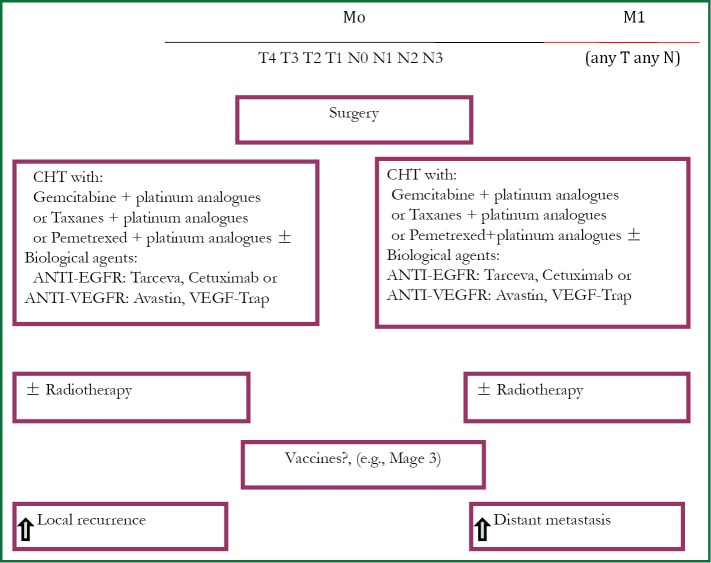

Figure 1.

Treatment algorithm for NSCLC. (T, tumor; Ν, lymphnodes; Μ, metastasis).

Management of NSCLC according to the extent of the disease

Early disease stage I-IIIA

Stage IA

Once histopathological diagnosis is made, if the patients generally consider fit for radical treatment these will undergo surgical intervention. Usually lobectomy or greater resection is recommended rather than sublobar resections (wedge or segmentation). In patients with stage I NSCLC who may tolerate operative intervention but not a lobar or greater lung resection because of comorbid disease or decreases in pulmonary functions segmentectomy/anatomical resection is recommended over non-surgical interventions. Further management will base on initial extent of the disease, postoperative information and on patient preference and decision.

The use of pre-operative or post-operative chemotherapy or radiation therapy in stage I NSCLC is not recommended by small randomized studies.

Stage IB

The meta-analysis over review gave non-clear evidence-based for adjuvant or induction treatment in stage IB patients after radical tumor resection. Only selective patients and patients that are participating in protocols are candidates for further treatment.

Stage II

Patients with stage II are usually consider for multidisciplinary treatment strategies.

The administration of postoperative radiation therapy for the improvement of survival is not recommended in patients who undergo radical resection of stage II tumor with N1 lymph node metastasis [stage II (N1) NSCLC].

In patients who undergo radical resection of stage II tumor and are in a good physical condition, adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy should be offered between 4th and 8th week following the thoracotomy (adequate wood healing, non residual inflammatory or infectious complications). Patients in stage II, who are not candidates for surgical approaches due to comorbidities (e.g., pulmonary risk factors), could be considered for chemo-radiotherapy strategies.

Locally advanced IIIA and selected IIIB

Patients in stage IIIA1-IIIA2 (3) are usually operated with mediastinal lymphadenectomy followed by platinum-based of adjuvant chemotherapy.

Postoperative radiation therapy alone can reduce the relapse locally without increasing survival.

A multidisciplinary management of IIIA3 and IIIA4 patients becomes crucial. Patients with proven N2 involvement (IIIA3 and IIIA4) could be treated by induction chemotherapy followed by surgery followed by platinum-based chemo radiotherapy.

Stage IIIB is typically considered for concurrent chemo radiotherapy approaches. In selected cases surgery will be incorporated within clinical trials.

Until now there is an obscure evidence of a randomized phase III pre-operative trials (Table 1).

Table 1. New adjuvant treatment.

| Theory | Reality |

|---|---|

| Micrometastasis reduction | Unknown |

| Downstaging | 50% |

| Patient acceptance increase | +++ |

| Relapse rate increase | ± |

| Morbidity/mortality increase | ± |

| Survival increase | ± |

Nevertheless a meta-analysis from five randomized trials of cisplatin-based therapy revealed a survival benefit for adjuvant chemotherapy (HR for death =0.89; 99% CI: 0.82 to 0.96; P=0.005) (4).

Management of advanced non-small cell lung cancer stage IIIB-IV

Patients of stage IIIB-IV should understand that the treatment goals are the prolongation of life, the palliation of symptoms and the improvement of QoL.

Chemotherapy vs. best supportive care (BSC)

A number of randomized studies compared the overall survival of NSCLC patients in stage IIIB and IV between chemotherapy and BSC and they revealed a real advantage for chemotherapy treatment (Table 2).

Table 2. Randomized clinical trials (including more than 100 pts) of platinum-based chemotherapy plus BSC vs. BSC in advanced NSCLC.

| Authors | Cytotoxic drugs | No of pts drugs/BSC | MS (mos) drugs/BSC | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rapp et al./1988 (5) | CAP | 198/53 | 5.7/3.9 | 0.05 |

| Woods et al./1990 (6) | Vdp | 7.5/3.9 | 0.01 | |

| Thongprasert et al./1999 (7) | IErP/MVdp | 189/98 | 6.0/2.5 | 0.006 |

| Cullen et al./1999 (8) | MIP | 175/175 | 6.7/4.8 | 0.03 |

| Spiro et al./2004 (9) | Cisplatin-based, MMC-Ifo-CDDP, MMC-VDS-CDDP, CDDP-VDS, CDDP-VNR | 364/361 | 8/5.7 | 0.01 |

Cytotoxic agents active against NSCLC are platinum analogues (cisplatin-carboplatin), ifosfamide, mytomycin C, vindesine, vinblastine, etoposide, gemcitabine, paclitaxel, docetaxel, vinorelbine, pemetrexed.

In the guidelines of ACCP, ASCO, FNCLCC and the Ontario Program, chemotherapy of advanced stage IIIB/IV pts, should be platinum-based with a new (3rd generation) single-agent. In Table 3 is presented the response in 3rd generation cytotoxic drugs as monotherapy and in combination with platinum analogues (10). In Tables 4,5,6 are presented the results from Phase I/III studies of 3rd generation cytotoxic agents in combination with older agents. Non-platinum containing chemotherapy may be used as an alternative to platinum-based regimen (Table 7).

Table 3. Results of six new agents in advanced NSCLC as monotherapy and in combination with platinum analogues (Pt) (10).

| Agent | Complete response + Partial response | Complete response + Partial response combination with (Pt) analogues |

|---|---|---|

| Vinorelbine | >15% | 30-45% (C) |

| Gemcitabine | >15% | 28-54% (C) |

| Paclitaxel | >15% | 27-44% (C) |

| Docetaxel | >15% | 25-62% (C) |

| Docetaxel | >15% | 26-51% (Cb) |

| Irinotecan | >15% | 50% (C) |

| Pemetrexed | <15% | 30.6% (C) |

Table 4. Phase I/II studies of taxanes plus carboplatines in advanced NSCLC.

| Study | References | Paclitaxel (P) Docetaxel (D) | Carboplatin | Patients (n) | Objective response | Median survival wk | Patients alive at 1 year % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Langer | (11) | 175-280 mg/m2 (P) | 7,5 | 22 | 12 (55%) | 54 | 56% |

| Langer | (12) | 135-215 mg/m2 (P) | 7,5 | 35 | 9 (26%) | NR | NR |

| Bunn | (13) | 135-250 mg/m2 (P) | 300-400 mg/m2 | 50 | 13 (26%) | 29 | 28% |

| Natale | (14) | 150-250 mg/m2 (P) | 6 | 42 | 26 (62%) | NR | NR |

| Rowinsky | (15) | 175-250 mg/m2 (P) | 7-9 | 19 | 7 (37%) | NR | NR |

| DeVore | (16) | 200 mg/m2 (P) | 6 | 63 | 16 (25%) | 32 | NR |

| Creaven | (17) | 175-250 mg/m2 (P) | 4,5 | 23 | 4 (17%) | NR | NR |

| Roychowdhury | (18) | 225 mg/m2 (P) | 6 (day 2) | 7 | 4 (57%) | NR | NR |

| Greco | (19) | 225 mg/m2 (P) | 6 | 100 | 38 (38%) | 35 | 42% |

| Camp | (20) | 175 mg/m2 (P) | 9,11 | 100 | 38 (38%) | 53 | 50% |

| Conner | (21) | 135 mg/m2 (P) | 4 | 15 | 2 (3%) | NR | NR |

| Zarogoulidis et al. | (22) | 100 mg/m2 (D) | 6 | 94 | 46 (54.7%) | 53 | 32% |

Table 5. Phase III trials of multidrug combinations incorporating newer agents in the treatment of advance NSCLC.

| New agent | First author | Patients (n) | Chemotherapy regimens | Response rates (%) | Median survival weeks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vinorelbine | Le Chevalier et al., 2001 (23) | 412 | Vinorelbine | 14 | 36 |

| Vinorelbine, cisplatin | 30* | 43* | |||

| Depierre (24) | 231 | Vinorelbine | 16 | 32 | |

| Vinorelbine, cisplatin | 43* | 33 | |||

| Baldini et al., 1998 (25) | 140 | Vinorelbine, carboplatin | 14 | 34 | |

| Vinorelbine, cisplatin, ifosfamide | 17 | 38 | |||

| Cisplatin, vindesine, mitomycin | 14 | 36 | |||

| Wozniak (26) | 432 | Cisplatin | 12 | 26 | |

| Vinorelbine, cisplatin | 26 | 35 | |||

| Frasci (27) | 120 | Vinorelbine | 15 | 18 | |

| Vinorelbine, gemcitabine | 22 | 29 | |||

| Paclitaxel/Docetaxel | Kelly et al., 2001 (28) | 406 | Vinorelbine, cisplatin | 28 | 32 |

| Paclitaxel, carboplatin | 24 | 34 | |||

| Giaccone (29) | 332 | Paclitaxel 175, cisplatin | 44 | 41 | |

| Cisplatin, teniposite | 30 | 42 | |||

| Gatzemeier (30) | 414 | Cisplatin 100 | 17 | 37 | |

| Paclitaxel 175, cisplatin 80 | 26* | 35 | |||

| Bonomi (31) | 599 | Paclitaxel 250, cisplatin | 28* | 44* | |

| Paclitaxel 135, cisplatin | 25* | 41* | |||

| Cisplatin, etoposide | 12 | 33 | |||

| Schiller et al., 2002 (32) | 1,207 | Cisplatin, paclitaxel | 21 | 32 | |

| Cisplatin, gemcitabine | 22 | 30 | |||

| Cisplatin, docetaxel | 17 | 32 | |||

| Carboplatin, paclitaxel | 17 | 32 | |||

| Georgoulias et al. (33) | 302 | Docetaxel, cisplatin | 36* | 52 | |

| Docetaxel | 18 | 40 | |||

| Stathopoulos et al. (34) | 360 | Paclitaxel, vinorelbine | 46 | 44 | |

| Paclitaxel, carboplatin | 43 | 40 | |||

| Gemcitabine | Crino (35) | 307 | Gemcitabine, cisplatin | 38* | 37 |

| Cisplatin, mitomycin, ifosfamide (MIC) | 26 | 42 | |||

| Cardenal (36) | 135 | Gemcitabine, cisplatin | 41* | 38* | |

| Cisplatin, etoposide | 22 | 31 | |||

| Sander (37) | 522 | Cisplatin | 11 | 33 | |

| Gemcitabine, cisplatin | 30* | 38 | |||

| Comella et al. (38) | 180 | Gemcitabine, cisplain, vinorelbine | 47* | 51* | |

| Gemcitabine, cisplatin | 30 | 42* | |||

| Cisplatin, vinorelbine | 25 | 35 | |||

| Irinotecan (CPT-11) | Masuda (39) | 398 | Cisplatin 80, irinotecan 60 | 43 | 50 |

| Cisplatin 80, vindesine | 31 | 47 | |||

| Irinotecan 100 | 21 | 46 | |||

| Negoro (40) | 398 | Irinotecan, cisplatin | 44 | 50 | |

| Cisplatin, vindesine | 32 | 46 | |||

| Irinotecan | 21 | 46 | |||

| Pemetrexed | Scaglioti et al. (41) | 1,725 | Cisplatin, pemetrexed | 31 | 40 |

| Cisplatin, gemcitabine | 28 | 40 |

NR, not reported; NS, not significant; *, P<0.05.

Table 6. Response rate and survival with doublet vs. single-agent regimens and triplet vs. doublet regimens (10).

| No. of comparisons | No. of patients | Treatment effect P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Response rate | |||

| 2 vs. 1 agents | 33 | 7,175 | <0.001 |

| 3 vs. 2 agents | 35 | 4,814 | <0.001 |

| 1-year survival | |||

| 2 vs. 1 agents | 13 | 4,125 | <0.001 |

| 3 vs. 2 agents | 10 | 2,249 | 0.88 |

| Median survival | |||

| 2 vs. 1 agents | 30 | 6,022 | <0.001 |

| 3 vs. 2 agents | 30 | 4,550 | 0.97 |

Table 7. Phase I/II studies of non-platinum doublets in advanced NSCLC (10).

| Regimen | Studies (n) | Assessable patients (n) | RR (%) range AR | MS (months) | IYS (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gem/VNR | 6 | 286 | 19-73 | 41 | 9,12 | NR |

| Doc/VNR | 6 | 174 | 20-88 | 48 | 5,9 | 24 |

| Pac/Gem | 3 | 117 | 30-35 | 33 | NR | NR |

| Doc/Gem | 2 | 73 | 38-39 | 13 | 51 | |

| Doc/CPT-11 | 1 | 32 | 34 | 9,8 | 38 | |

| Pac/VNR | 1 | 25 | 16 | NR | NR | |

| Gem/Topotecan | 1 | 13 | 30 | NR | NR | |

Number of chemotherapy

Two randomized trials suggest that the survival benefit that pts receive from chemotherapy occurs in the first three to four cycles. Prolonged therapy may increase cumulative toxicities with insignificant increase in survival rates (42).

Concurrent vs. sequential chemo radiotherapy

Several phase III randomized trials of concurrent vs. sequential chemo-radiotherapy have revealed: (I) improved median survival time (average of 15.7 vs. 14 months) (43); (II) improved 2-year survival rates (35% vs. 23%) (44); (III) improved 5-year survival (15.8% vs. 8.9%, P=0.039) (45). On the other hand, an increased toxicity with an acute esophagitis incidence of 26% was observed in the concurrent arm (43).

Baggstrom et al., have performed a meta-analysis of the published literature comparing platinum-based regimens including a third-generation agent to older standard platinum-based regimens. The new third-generation regimens increased patient survival compared to the older regimens (RR, 1.14; 95% CI: 1.01 to 1.29). There was an absolute increase in the 1-year survival rate of 4% using the newer combination regimens compared to the older regimens (P=0.04) (46).

Treatment according to prognostic and predictive factors

Excision repair cross-complementation group 1 and regulatory subunit of ribonucleotide reductase (ERCC1, RRM1)

A number of studies have shown the importance of RRM1 and ERCC1 expressions (47,48) in tumor cells. High RRM1 and ERCC1 expression is associated with longer survival after resection of early stage NSCLC (prognostic). Additionally high RRM1 and ERCC1 expression are predictors of lower tumor response rate and shorter survival for treatment with gemcitabine and cisplatin (predictive). Finally low ERCC1 expression is associated with survival benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy for NSCLC (predictive). These biomarkers have not been prospectively validated.

Thymidylate synthase expression (TS)

Baseline expression of the TS gene and protein were significantly higher in squamous cell carcinoma when compared with adenocarcinoma (49). Preclinical data indicate that high expression of TS correlates with reduced sensitivity to cytotoxic agent pemetrexed (antifolate) (50). In JMDB study 1,700 primary untreated NSCLC pts of stage IIIB/IV and PS 0-1 were randomized either to cisplatin plus gemcitabine or ciplatin plus pemetrexed given every three weeks up to six cycles. Overall Survival found to be similar for both treatment arms (Median 10.3 mos; HR 0.94; 95%, CI: 0.84-1.05). Nevertheless, analysis of pts by histology showed a statistical significant better OS of non-squamous histology pts in cisplatin + pemetrexed arm compared to cisplatin + gemcitabine arm (11 vs. 10.1 mos) and this difference for those with adenocarcinoma was improved in the pemetrexed arm by 12.6 vs. 10.9 mos respectively (P=0.08). The results of JMDB study indicating a predictive role of tumor histology and cisplatin/pemetrexed has been registered in first line standard therapy in non-squamous NSCLC pts (41).

Biological agents

Progress in understanding cancer biology and mechanisms of oncogenesis has allowed the development of treatment against specific molecular targets, such as epidermal growth-factor receptor (EGFR) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which are of special interest in NSCLC.

The most frequently targeted pathways in NSCLC have involved the EGFR and the Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor and its Receptor (VEGF, VEGFR).

The EGFR is a member of ErbB family of transmembrane receptors Tyrosine Kinases (TKs) and plays a major role in the malignant cell phenotype.

The role of EGFR inhibitors in the first line setting as single agents was explored after the failure to show benefit in combination with chemotherapy. In the IPASS trial (51), 1,217 chemo naïve, East Asian with adenocarcinoma histology, never or light smokers pts randomized to receive the EGFR inhibitor gefitinib (G) or carboplatin plus placlitaxel (CP). The trial demonstrating superior PFS in the gefitinib arm compared with CP (HR 0.74; 95%, CI: 0.65-0.85; P<0.0001) and Overall Response Rate (43% vs. 32.2%; P=0.0001) but similar Overall Survival (median mos 18.6 vs. 17.3). Patients with EGFR mutations had the most benefit from gefitinib, with a 51% reduction in progression (HR 0.48; P<0.0001) whereas those pts without EGFR mutation, responded better to chemotherapy (P<0.0001).

Erlotinib inhibits the tyrosine kinase activity of EGFR and has been studied extensively in randomized Phase III trials, yielding promising results, especially as second-line, third line, and maintenance therapy, and in patients with activating mutations of the EGFR receptor.

In the EURTAC multicentre, randomized phase III trial (52), 174 non-squamous EGFR mutant patients received platinum-based chemotherapy or Erlotinib. Median PFS was 9.7 mos in the erlotinib group compared with 5.2 mos in the chemotherapy group (P<0.0001).

Angiogenesis place a critical role in tumor development. Anti-angiogenic therapy such as the use of TKIs that block the VEGFR, aims to disrupt existing capillaries that feed a tumor and prevent new vessels from forming around it.

In two randomized phase III studies the ECOG 4599 (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group) (53) and AVAiL (AVAstin in Lung) (54) the adding of anti-angiogenetic agent bevacizumab to paclitaxel/carboplatin in the first and to gemcitabine/cisplatin in the 2nd study, indicated improved of efficacy and PFS [(6.2 vs. 4.5 mos, P<0.0001) and (P=0.003 for a dose of bevacizumab of 7.5 mg/kg or P=0.03 for a dose of bevacizumab of 15 mg/kg respectively)].

All the including in the two above studies pts were chemotherapy naïve ECOG PS of O or 1 with newly diagnosed stage IIIB/IV and non-squamous NSCLC confirmation.

In the ECOG 4599 study there was a statistical significant improvement even in OS in the arm receiving bevacizumab compared to the control arm (HR 0.79; 95%, CI: 0.67-0.92; P=0.003). Based on the results of ECOG 4599 and AVAiL, the use of bevacizumab is recommended in combination with chemotherapy in non-squamous cell carcinoma (limitations, clinical significant hemoptysis, as controlled, hypertension, therapeutic anticoagulation).

More recently, the BeTa (Bevacizumab/Tarceva) trial (55), investigating the benefits of addition of bevacizumab to erlotinib for second-line treatment of advanced NSCLC, showed a doubling of progression-free survival with combination therapy (3.4 months) as compared with erlotinib monotherapy (1.7 months, P=0.001) but no benefit in terms of overall survival.

In another randomized trial (56), each targeted therapy alone (bevacizumab, erlotinib) compared with their combination and cytotoxic platinum-based chemotherapy alone in previously untreated and advanced non-squamous NSCLC, following by administration of these agents as maintenance therapy.

This randomized study suggests that bevacizumab enhances the activity of chemotherapy but this did not translate into longer overall survival.

Acknowledgements

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin 2008;58:71-96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chansky K, Sculier JP, Crowley JJ, et al. The International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Staging Project: prognostic factors and pathologic TNM stage in surgically managed non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2009;4:792-801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robinson LA, Ruckdeschel JC, Wagner H Jr, et al. Treatment of non-small cell lung cancer-stage IIIA: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (2nd edition). Chest 2007;132:243S-265S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pignon JP, Tribodet H, Scagliotti GV, et al. Lung adjuvant cisplatin evaluation: a pooled analysis by the LACE Collaborative Group. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:3552-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rapp E, Pater JL, Willan A, et al. Chemotherapy can prolong survival in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer--report of a Canadian multicenter randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 1988;6:633-41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woods RL, Williams CJ, Levi J, et al. A randomised trial of cisplatin and vindesine versus supportive care only in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer 1990;61:608-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis using updated data on individual patients from 52 randomised clinical trials. Non-small Cell Lung Cancer Collaborative Group. BMJ 1995;311:899-909 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cullen MH, Billingham LJ, Woodroffe CM, et al. Mitomycin, ifosfamide, and cisplatin in unresectable non-small-cell lung cancer: effects on survival and quality of life. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:3188-94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spiro SG, Rudd RM, Souhami RL, et al. Chemotherapy versus supportive care in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: improved survival without detriment to quality of life. Thorax 2004;59:828-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zarogoulidis K. New Drugs in Lung Cancer, ERS school courses 2003, 27th-30th November 2003, Lausanne, Switzerland.

- 11.Langer CJ, Millenson M, Rosvold E, et al. Paclitaxel (1-hour) and carboplatin (area under the concentration-time curve 7.5) in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a phase II study of the Fox Chase Cancer Center and its network. Semin Oncol 1997;24:S12-81-S12-88. [PubMed]

- 12.Langer CJ, Leighton JC, Comis RL, et al. Paclitaxel and carboplatin in combination in the treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase II toxicity, response, and survival analysis. J Clin Oncol 1995;13:1860-70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelly K, Pan Z, Murphy J, et al. A phase I trial of paclitaxel plus carboplatin in untreated patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res 1997;3:1117-23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Natale RB. A phase I/II trial of combination paclitaxel and carboplatin in advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer: preliminary results of an ongoing study. Semin Oncol 1995;22:34-7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rowinsky EK, Flood WA, Sartorius SE, et al. Phase I study of paclitaxel on a 3-hour schedule followed by carboplatin in untreated patients with stage IV non-small cell lung cancer. Invest New Drugs 1997;15:129-38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeVore RF 3rd, Jagasia M, Johnson DH. Paclitaxel by either 1-hour or 24-hour infusion in combination with carboplatin in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: preliminary results comparing sequential phase II trials. Semin Oncol 1997;24:S12-27-S12-29. [PubMed]

- 17.Creaven PJ, Raghavan D, Pendyala L, et al. Paclitaxel and carboplatin in early phase studies: Roswell Park Cancer Institute experience in the subset of patients with lung cancer. Semin Oncol 1997;24:S12-138-S12-143. [PubMed]

- 18.Roychowdhury DF, Desai P, Zhu YW. Paclitaxel (3-hour infusion) followed by carboplatin (24 hours after paclitaxel): a phase II study in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Semin Oncol 1997;24:S12-37-S12-40. [PubMed]

- 19.Greco FA, Hainsworth JD. Paclitaxel (1-hour infusion) plus carboplatin in the treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer: results of a multicenter phase II trial. Semin Oncol 1997;24:S12-14-S12-17. [PubMed]

- 20.Camp MJ, Fanucchi M. High dose carboplatin in combination with paclitaxel for advanced NSCLC (abstract) Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1997;16:464A [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conner AC, Mitchell RD. Biweekly carboplatin and paclitaxel for advanced NSCLC (abstract) Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 1997;16:465Q [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zarogoulidis K, Kontakiotis T, Hatziapostolou P, et al. A Phase II study of docetaxel and carboplatin in the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2001;32:281-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Le Chevalier T, Brisgand D, Soria JC, et al. Long term analysis of survival in the European randomized trial comparing vinorelbine/cisplatin to vindesine/cisplatin and vinorelbine alone in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Oncologist 2001;6Suppl 1:8-11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Depierre A, Lagrange JL, Theobald S, et al. Summary report of the Standards, Options and Recommendations for the management of patients with non-small-cell lung carcinoma (2000). Br J Cancer 2003;89Suppl 1:S35-49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baldini E, Tibaldi C, Ardizzoni A, et al. Cisplatin-vindesine-mitomycin (MVP) vs cisplatin-ifosfamide-vinorelbine (PIN) vs carboplatin-vinorelbine (CaN) in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC): a FONICAP randomized phase II study. Italian Lung Cancer Task Force (FONICAP). Br J Cancer 1998;77:2367-70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wozniak AJ, Crowley JJ, Balcerzak SP, et al. Randomized trial comparing cisplatin with cisplatin plus vinorelbine in the treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a Southwest Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 1998;16:2459-65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frasci G, Lorusso V, Panza N, et al. Gemcitabine plus vinorelbine versus vinorelbine alone in elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:2529-36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelly K, Crowley J, Bunn PA, et al. A randomized phase III trial of paclitaxel plus carboplatin (PC) versus vinorelbine plus cisplatin (VC) in untreated advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): a southwest oncology group trial. J Clin Oncol 2000;19:3210-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Giaccone G, Herbst RS, Manegold C, et al. Gefitinib in combination with gemcitabine and cisplatin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III trial--INTACT 1. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:777-84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gatzemeier U, von Pawel J, Gottfried M, et al. Phase III comparative study of high-dose cisplatin versus a combination of paclitaxel and cisplatin in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:3390-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bonomi P, Kim K, Fairclough D, et al. Comparison of survival and quality of life in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with two dose levels of paclitaxel combined with cisplatin versus etoposide with cisplatin: results of an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group trial. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:623-31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schiller JH, Harrington D, Belani CP, et al. Comparison of four chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2002;346:92-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Georgoulias V, Ardavanis A, Tsiafaki X, et al. Vinorelbine plus cisplatin versus docetaxel plus gemcitabine in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase III randomized trial. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:2937-45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stathopoulos GP, Veslemes M, Georgatou N, et al. Front-line paclitaxel-vinorelbine versus paclitaxel-carboplatin in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomized phase III trial. Ann Oncol 2004;15:1048-55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Crinò L, Scagliotti GV, Ricci S, et al. Gemcitabine and cisplatin versus mitomycin, ifosfamide, and cisplatin in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: A randomized phase III study of the Italian Lung Cancer Project. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:3522-30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cardenal F, López-Cabrerizo MP, Antón A, et al. Randomized phase III study of gemcitabine-cisplatin versus etoposide-cisplatin in the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 1999;17:12-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sandler AB, Nemunaitis J, Denham C, et al. Phase III trial of gemcitabine plus cisplatin versus cisplatin alone in patients with locally advanced or metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:122-30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Comella P, Frasci G, Panza N, et al. Randomized trial comparing cisplatin, gemcitabine, and vinorelbine with either cisplatin and gemcitabine or cisplatin and vinorelbine in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: interim analysis of a phase III trial of the Southern Italy Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol 2000;18:1451-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Masuda N, Fukuola M, Negoro S, et al. Randomized trial comparing cisplastin and irinotecan versus cisplastin and vindesine versus CPT-11 in advanced non-small cell lung cancer, a multicenter phase III study. Proc Am Soc CLin Oncol 1999;18:459a [Google Scholar]

- 40.Negoro S, Masuda N, Takada Y, et al. Randomised phase III trial of irinotecan combined with cisplatin for advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer 2003;88:335-41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scagliotti GV, Parikh P, von Pawel J, et al. Phase III study comparing cisplatin plus gemcitabine with cisplatin plus pemetrexed in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:3543-51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith IE, O'Brien ME, Talbot DC, et al. Duration of chemotherapy in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomized trial of three versus six courses of mitomycin, vinblastine, and cisplatin. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:1336-43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arriagada R, Bergman B, Dunant A, et al. Cisplatin-Based Adjuvant Chemotherapy in Patients with Completely Resected Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N Engl J Med 2004;350:351-60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.French Cooperative Group Study ASCO Proc 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 45.The West Japan Lung Cancer Group Study JCO 1999.

- 46.Baggstrom MQ, Stinchcombe TE, Fried DB, et al. Third-generation chemotherapy agents in the treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis. J Thorac Oncol 2007;2:845-53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Olaussen KA, Dunant A, Fouret P, et al. DNA repair by ERCC1 in non-small-cell lung cancer and cisplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy. N Engl J Med 2006;355:983-91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Soria J, Haddad V, Dlaussen KA, et al. Immunohistochemical staining of the excision repair cross-complementing 1 (ERCC1) protein as predictor for benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy (CT) in the international lung cancer trial (IALT). J Clin Oncol 2006;24:abstr 7010.

- 49.Ceppi P, Volante M, Saviozzi S, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the lung compared with other histotypes shows higher messenger RNA and protein levels for thymidylate synthase. Cancer 2006;107:1589-96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sigmond J, Backus HH, Wouters D, et al. Induction of resistance to the multitargeted antifolate Pemetrexed (ALIMTA) in WiDr human colon cancer cells is associated with thymidylate synthase overexpression. Biochem Pharmacol 2003;66:431-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fukuoka M, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, et al. Biomarker analyses and final overall survival results from a phase III, randomized, open-label, first-line study of gefitinib versus carboplatin/paclitaxel in clinically selected patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer in Asia (IPASS). J Clin Oncol 2011;29:2866-74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R, et al. Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:239-46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ramalingam SS, Dahlberg SE, Langer CJ, et al. Outcomes for elderly, advanced-stage non small-cell lung cancer patients treated with bevacizumab in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel: analysis of Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Trial 4599. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:60-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reck M, von Pawel J, Zatloukal P, et al. Phase III trial of cisplatin plus gemcitabine with either placebo or bevacizumab as first-line therapy for nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer: AVAil. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:1227-34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Herbst RS, Ansari R, Bustin F, et al. Efficacy of bevacizumab plus erlotinib versus erlotinib alone in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer after failure of standard first-line chemotherapy (BeTa): a double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2011;377:1846-54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Boutsikou E, Kontakiotis T, Zarogoulidis P, et al. Docetaxel-carboplatin in combination with erlotinib and/or bevacizumab in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Onco Targets Ther 2013;6:125-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]