Abstract

Objective

To perform a systematic review of the literature on the prevalence of cognitive impairment and dementia in sub-Saharan Africa.

Methods

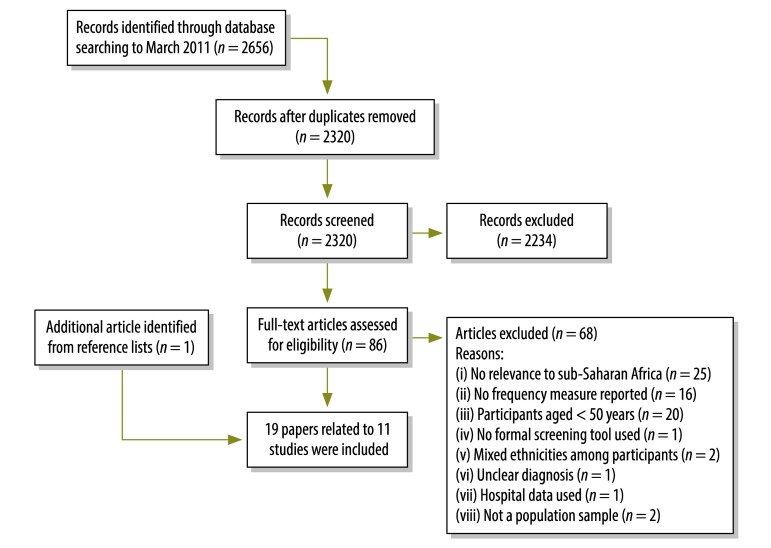

Five electronic databases were searched for relevant abstracts and to identify papers eligible for full-text review. A study was included if two authors agreed that it had a cohort, case–control or cross-sectional design and reported population-level data; was limited to black African adults older than 50 years or described as “elderly” or “old”; reported data for individuals residing in sub-Saharan Africa; and reported at least one measure of cognitive impairment or clinical outcomes relevant to cognitive decline. References of papers included in our study were searched to identify additional candidate publications. Disagreements about inclusion were adjudicated during discussions involving all authors. Data were extracted independently by two authors, using a form developed by the authors and tested on a sample of papers.

Findings

A total of 2320 unique papers was found; the full text of 87 was reviewed. Nineteen papers featuring 11 cross-sectional studies were included; all were published during 1995–2011. Studies occurred in Benin, Botswana, the Central African Republic, the Congo and Nigeria and enrolled approximately 10 500 participants. The prevalence of dementia ranged from 0%, in Nigeria, to 10.1% (95% confidence interval, CI: 8.6–11.8), also in Nigeria. The prevalence of cognitive impairment ranged from 6.3%, in Nigeria, to 25% (95% CI: 21.2–29.0), in the Central African Republic.

Conclusion

Prevalences of dementia and cognitive impairment in sub-Saharan Africa varied widely, with few published studies revealed by the literature search.

Résumé

Objectif

Réaliser une étude systématique de la littérature consacrée à la prévalence de la déficience cognitive et de la folie en Afrique subsaharienne.

Méthodes

Cinq bases de données ont été fouillées afin de trouver des résumés pertinents et d'identifier les journaux éligibles pour une étude en texte intégral. Une étude était inclue si deux auteurs reconnaissaient qu'elle était de type cohorte, cas-témoins ou transversale et relevait des données de l’l'échelle de la population; qu'elle était limitée aux adultes africains noirs âgés de plus de 50 ans ou décrits comme «âgés» ou «vieux»; qu'elle relevait des données concernant des individus résidant en Afrique subsaharienne; et qu'elle relevait au moins une mesure de déficience cognitive ou de résultats cliniques liés au déclin cognitif. Les références de journaux inclus dans notre étude ont été fouillées pour identifier des publications supplémentaires potentielles. Les désaccords quant à une inclusion étaient réglés au cours de discussions impliquant tous les auteurs. Des données étaient extraites indépendamment par deux auteurs, au moyen d'un formulaire développé par les auteurs et testées sur un échantillon de journaux.

Résultats

Au total, 2320 journaux uniques ont été trouvés; le texte intégral de 87 d'entre eux a été analysé. Dix-neuf journaux présentant 11 études transversales ont été inclus; tous avaient été publiés entre 1995 et 2011. Les études avaient eu lieu au Bénin, au Botswana, en République centrafricaine, au Congo et au Nigéria et impliquaient environ 10 500 participants. La prévalence de la démence allait de 0% au Nigéria à 10,1% (intervalle de confiance 95%, IC: 8,6-11,8) également au Nigéria. La prévalence de la déficience cognitive allait de 6,3% au Nigéria à 25% (IC 95%: 21,2-29,0) en République centrafricaine.

Conclusion

Les prévalences de démence et de déficience cognitive en Afrique subsaharienne variaient sensiblement et peu d'études publiées ont été révélées par la recherche de littérature.

Resumen

Objetivo

Realizar una revisión sistemática de la literatura sobre la prevalencia del deterioro cognitivo y la demencia en el África subsahariana.

Métodos

Se hicieron búsquedas en cinco bases de datos electrónicas a fin de hallar resúmenes pertinentes e identificar los documentos que cumplieran con los requisitos para una revisión del texto completo. Los estudios se incluyeron cuando dos autores coincidían en que el diseño era de cohorte, de casos y controles o transversal y si presentaban los datos a nivel de población, si se limitaban a los adultos africanos negros mayores de 50 años o descritos como "personas mayores" o "ancianas", si incluían datos correspondientes a las personas que residen en el África subsahariana y si presentaban, al menos, un grado de deterioro cognitivo o resultados clínicos relevantes sobre el deterioro cognitivo. Se realizaron búsquedas de las referencias de los artículos incluidos en nuestro estudio a fin de identificar más publicaciones que cumplieran los requisitos, se arbitraron los desacuerdos sobre la inclusión en las discusiones que involucraban a todos los autores y se recogieron los datos de forma independiente por dos autores mediante un formulario desarrollado por los autores y probado en una muestra de trabajos.

Resultados

Se halló un total de 2320 documentos únicos y se revisó el texto completo de 87 de ellos. Se seleccionaron diecinueve documentos que incluían 11 estudios transversales, todos ellos publicados entre 1995 y 2011. Los estudios tuvieron lugar en Benin, Botswana, la República Centroafricana, el Congo y Nigeria, en los que se registraron aproximadamente 10 500 participantes. La prevalencia de la demencia varió del 0 % en Nigeria, al 10,1 % (intervalo de confianza del 95 %, IC: 8,06-11,08), también en Nigeria. La prevalencia del deterioro cognitivo varió del 6,3 % en Nigeria, al 25 % (IC del 95 %: 21,2 a 29,0) en la República Centroafricana.

Conclusión

La prevalencia de la demencia y el deterioro cognitivo en el África subsahariana variaron mucho, y fueron pocos los estudios publicados que se revelaron mediante la búsqueda bibliográfica.

ملخص

الغرض

إجراء استعراض منهجي للمؤلفات حول انتشار الخلل الإدراكي والخرف في أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء الكبرى.

الطريقة

تم البحث في خمس قواعد بيانات إلكترونية عن الملخصات ذات الصلة وللتعرف على الأوراق البحثية التي تصلح لاستعراض نصوصها الكاملة. وكانت الدراسة صالحة للتضمين إذا اتفق اثنان من المؤلفين على أنها ذات تصميم متناسق، أو لحالات مرتبطة بضوابط أو ذات تصميم مقطعي، وأبلغت عن بيانات على مستوى السكان؛ واقتصرت على الأشخاص البالغين الأفارقة السود الأكبر من 50 عاماً أو الذين يوصفون بأنهم "مسنين" أو "كبار السن"؛ وأبلغت عن بيانات للأفراد المقيمين في أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء الكبرى؛ وأبلغت عن مقياس واحد على الأقل للخلل الإدراكي أو النتائج السريرية المتصلة بالتدهور الإدراكي. وتم البحث في مراجع الأوراق البحثية المتضمنة في دراستنا لتحديد المنشورات الإضافية المقترحة. وكان الفصل في الخلافات بشأن التضمين يتم من خلال مناقشات يشترك فيها كل المؤلفين. وتم استخلاص البيانات بشكل مستقل بواسطة اثنين من المؤلفين، باستخدام استمارة وضعها المؤلفون وتم اختبارها على عينة من الأوراق البحثية.

النتائج

تم العثور على إجمالي 2320 ورقة بحثية فريدة؛ وتم استعراض النص الكامل لسبع وثمانين دراسة منها. وتم تضمين تسع عشرة ورقة بحثية تضم 11 دراسة مقطعية؛ وقد نشرت كلها خلال الفترة من 1995 إلى 2011. وأجريت الدراسات في بنين وبتسوانا وجمهورية أفريقيا الوسطى والكونغو ونيجيريا، وأدرجت حوالي 10500 مشارك. وتراوح انتشار الخرف من 0 % في نيجيريا، إلى 10.1 % (فاصل الثقة 95 %، فاصل الثقة: 8.6–11.8)، أيضاً في نيجيريا. وتراوح انتشار الخلل الإدراكي من 6.3 %، في نيجيريا، إلى 25 % (فاصل الثقة 95 %، فاصل الثقة: 21.2–29.0) في جمهورية أفريقيا الوسطى.

الاستنتاج

تباينت معدلات انتشار الخرف والخلل الإدراكي في أفريقيا جنوب الصحراء الكبرى بقدر واسع، مع وجود القليل من الدراسات المنشورة التي كشف عنها البحث في المؤلفات.

摘要

目的

进行撒哈拉以南非洲认知障碍和痴呆发病率相关文献的系统评价。

方法

检索五个电子数据库的相关摘要,并确定出符合全文评价条件的文章。将研究纳入的条件是:有两位作者同意某研究具有队列、病例对照或横断面设计并且报告了群体水平的数据;研究限于年龄在 50 岁以上或被描述为“上年纪”或“年老”的非洲成年黑人;报告居住在撒哈拉以南非洲个体的数据;报告至少一种认知障碍或认知衰退相关临床结果的量度。对于我们研究中所纳入的文章,也对其参考文献进行检索,以确定更多的其他候选发表文章。在涉及所有作者的讨论中对有关是否纳入的分歧进行评判。数据由两位作者独立提取,提取时使用了作者编制并在论文样本上进行过检测的表格。

结果

总计找到 2320 篇单独的文章;对 87 篇全文进行评价。纳入了 11 项横断面研究的 19 篇文章;所有文章都发表于 1995–2011 年间。这些研究在贝宁、博茨瓦纳、中非共和国、刚果和尼日利亚开展,招募了约 1.05 万名患者。痴呆的发病率范围在尼日利亚的 0% 到同样是尼日利亚的 10.1%(95% 置信区间,CI:8.6–11.8)之间。认知障碍的发病率范围在尼日利亚的 6.3% 到中非共和国的 25% 之间(95% CI:21.2–29.0)。

结论

痴呆和认知障碍的发病率在撒哈拉沙漠以南非洲差异巨大,通过文献检索发现的已发表研究很少。

Резюме

Цель

Выполнить систематический обзор публикаций, посвященных распространенности когнитивных нарушений и деменции в странах Африки к югу от Сахары.

Методы

Поиск выдержек подходящей тематики и публикаций для полнотекстового обзора был выполнен в пяти базах данных. Исследование включалось в обзор в том случае, если, по мнению двух авторов, оно проводилось либо по когортной схеме, либо по перекрестной схеме, либо по схеме «случай–контроль», а его результатами были данные на уровне популяции;касалось исключительно чернокожих африканцев в возрасте старше 50 лет или описывавшихся как «пожилые» или «старые»; содержало сведения о жителях стран Африки к югу от Сахары; в нем упоминалось как минимум об одном параметре когнитивных нарушений или клинических исходах, связанных с ухудшением когнитивной функции. Дополнительный поиск публикаций-кандидатов, заслуживавших включения в обзор, проводился по ссылкам из работ, охваченных нашим исследованием. Урегулирование разногласий относительно возможности включения публикации в обзор осуществлялось посредством обсуждения с привлечением всего авторского коллектива. Извлечение данных осуществлялось двумя авторами независимо друг от друга при помощи авторской формы, апробированной на ряде тестовых публикаций.

Результаты

Всего было обнаружено 2 320 отдельных публикаций; 87 из них были подвергнуты полнотекстовому анализу. В обзор вошли девятнадцать публикаций, вышедших в 1995–2011 гг.; в одиннадцати из них были представлены материалы перекрестных исследований. Исследования проводились в Бенине, Ботсване, Конго, Нигерии и Центральноафриканской Республике и охватили около 10 500 человек. Распространенность деменции варьировалась от 0% в Нигерии до 10,1% (доверительный интервал (ДИ) 95%: от 8,6 до 11,8) также в Нигерии. Распространенность когнитивных нарушений варьировалась от 6,3% в Нигерии до 25% (ДИ 95%: от 21,2 до 29,0) в Центральноафриканской Республике.

Вывод

По данным нескольких опубликованных исследований, обнаруженных в результате поиска литературы, распространенность деменции и когнитивных нарушений в странах Африки к югу от Сахары существенно разнится.

Introduction

The prevalence of age-related health problems is becoming an important public health concern as proportions of older individuals in populations worldwide grow.1 Dementia is one of the major causes of disability in older people.2 It is a complex syndrome characterized by global and irreversible cognitive decline that is severe enough to undermine daily functioning.3 Dementia is a chronic illness that arises from an interplay of genetic, environmental and behavioural factors, with severe adverse influences on social and physical activities and quality of life. In cognitive impairment and mild cognitive impairment, the cognitive deficit is less severe than in dementia and normal daily function and independence are generally maintained. It is a chronic condition that is a precursor to dementia in up to one third of cases.3

Cognitive impairment and dementia are increasing globally and are predicted to increase proportionately more in developing regions.1,4–6 Projections indicate that by 2050 the number of individuals older than 60 years will be approximately 2 billion and will account for 22% of the world’s population. Four fifths of the people older than 60 years will be living in developing countries in Africa, Asia or Latin America.7 It is estimated that 35.6 million people are currently living with dementia worldwide and that the number will nearly double every 20 years, reaching 115.4 million in 2050, with the majority living in developing countries.8 Of the total number of people with dementia worldwide, 57.7% lived in developing countries in 2010 and a proportionate increase to 70.5% by 2050 is anticipated.8 Consequently, the health and social burden of cognitive impairment and dementia will rise dramatically in these regions.9 Developing countries, including those in sub-Saharan Africa, are currently undergoing a demographic and epidemiological transition and the impact of population ageing in sub-Saharan Africa will increasingly augment the burden of noncommunicable and degenerative diseases in this region.

Few studies to determine the prevalence of dementia have been conducted in sub-Saharan Africa.10,11 Early studies12 showed a lower prevalence than in Europe11,13 and the United States of America, where approximately 6.2% and 8%, respectively, of people aged 65 years or older are reported to have dementia.14–16 The aim of this study was to perform a systematic review of the literature to obtain the best available estimates of the prevalences of cognitive impairment and dementia in sub-Saharan Africa and to identify gaps in current research.

Methods

A systematic review of studies reporting the prevalences of dementia and cognitive impairment among older black Africans in sub-Saharan Africa countries was conducted according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.17

Search strategy

We searched the following databases between February and May 2011: PubMed (search range, 1950 to week 18 of 2011); the Web of Knowledge, which includes the Web of Science Conference Proceedings Citation Index (1970 to week 18 of 2011), the BIOSIS Citation Index (1969 to week 18 of 2011), Journal Citation Reports (1997–2008) and CAB Abstracts (1973 to week 18 of 2011); EMBASE (1947 to week 18 of 2011); ASSIA (1987 to week 18 of 2011) and PsycNET (1894 to week 18 of 2011). The search terms used included variations across the following broad terms: epidemiology, prevalence, incidence, cognition, cognitive impairment, dementia, Alzheimer disease, sub-Saharan Africa, names of individual sub-Saharan African countries, elderly and older people. Searches incorporated MeSH (medical subject heading) terms or equivalents, exploded terms and text word terms (Appendix A, available at: http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/med/research/hscience/research/dementia/). We checked the reference lists of retrieved articles for further relevant studies.

Study selection

Studies were included if they satisfied all of the following criteria: (i) the study had a cohort, case–control or cross-sectional study design and reported population-level data, defined as data from population surveys or patients identified in primary or community care samples; (ii) the study was limited to black African adults who were older than 50 years or described as “elderly” or “old” or, if the age range of subjects was broader, reported data separately for those older than 50 years; (iii) the study population resided in sub-Saharan Africa or, if the geographic area of residence was broader, reported data separately for those residing in sub-Saharan Africa; and (iv) the study reported at least one measure of cognitive impairment or clinical outcomes relevant to cognitive decline (i.e. dementia, Alzheimer disease, amnesia and/or confusion) and at least one measure of the frequency of cognitive impairment (i.e. prevalence and/or incidence).

No language restrictions were applied. All titles identified were screened independently for potential relevance by at least two authors and abstracts were obtained if the title was considered relevant by at least one author. Abstracts were screened in the same way. Finally, full texts of the remaining papers were assessed for eligibility and when two authors disagreed on inclusion a decision was made in discussion by all three authors.

Data extraction and analysis

Data were extracted from each paper independently by two authors, using a data collection form developed by the authors and tested on a sample of papers (Appendix B, available at: http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/med/research/hscience/research/dementia/). Details about the study design, participant characteristics, analysis methods and findings, and authors’ conclusions were entered into the form.

For studies in which several related papers were identified, the papers were evaluated collectively as one study for data extraction.12,15,16,18–23 In one paper, two studies were reported, and we considered these studies separately.24 Because of considerable heterogeneity in methods (sampling and study design), population samples (age, health, socioeconomic status, geographical region and cultural background) and screening or diagnostic measures, we did not pool the data but report our findings in narrative form.

Two authors independently evaluated the quality of the studies, using a standardized checklist. The following factors were assessed: whether the sample was representative of the target population, whether screening and diagnostic tools produced reliable and valid measures of psychiatric outcome and key concepts and whether the analysis accounted for special features of the sampling design and included confidence intervals.25

Results

Study characteristics

We retrieved 281 references from PubMed, 1081 from the Web of Knowledge, 55 from CAB Abstracts, 1192 from EMBASE, 43 from ASSIA and 4 from PsycNET. After removal of duplicates, 2320 references remained. Initial screening yielded 86 papers for full-text review and one additional reference was identified from searching reference lists of included papers. (Fig. 1). One additional reference was identified while searching reference lists of included papers. Our systematic review yielded 19 papers associated with 11 studies.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram for a systematic review of the literature to select studies evaluating the prevalences of dementia and cognitive impairment in sub-Saharan Africa

The studies reported findings for 10 413 participants. All studies were cross-sectional and were published between 1995 and 2011, with approximately two thirds published between 2005 and 2011 (Table 1). The studies were conducted in Benin, Botswana, the Central African Republic, the Congo and Nigeria; most occurred in Nigeria, in Ibadan, Dunukofia, Jos, Uwan and Zaria. Five studies included participants from both rural and urban settings, one study included only urban participants and five studies included only rural participants. All studies included participants aged 65 years and older; two studies also included participants aged 60–64 years. The mean age of the participants ranged between 72.0 and 76.1 years. All studies included both female and male participants and 10 studies reported prevalence data stratified by sex.

Table 1. Characteristics of the studies obtained from a systematic review of the literature on the prevalences of dementia and cognitive impairment in sub-Saharan Africa.

| Country, reference | Publication date | Study site |

Participants |

Prevalence of dementia, % (95% CI) |

Prevalence of cognitive impairment, % (95% CI) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area | Setting | No. | Age in years | Overall | By age in years | Overall | By age in years | |||||

| Benin | ||||||||||||

| Guerchet et al.26 | 2009 | Djidja | Rural | 502 | ≥ 65 | 2.6 (1.1–3.8) | 65–79: 1.1 (0.3–2.9) | 10.4 (7.7–13.1)a | 65–79: 6.5 (3.9–9.1) | |||

| ≥ 80: 6.0 (2.8–11.1) | ≥ 80: 26.6 (19.5–33.7) | |||||||||||

| Botswana | ||||||||||||

| Clausen et al.27 | 2005 | Nation-wide | Rural and urban | 372 | ≥ 60 | – | – | 9.0 | 60–69: 4.0 | |||

| 70–79: 9.0 | ||||||||||||

| ≥ 80: 20.0 | ||||||||||||

| Central African Republic | ||||||||||||

| Guerchet et al.24 | 2010 | Bangui | Rural | 496 | ≥ 65 | 8.1 (5.8–10.8) | 65–74: 5.4 (3.0–7.8) | 25 (21.2–29.0)a | 65–74: 26.3 (21.7–31.4) | |||

| 75–84: 11.6 (6.7–18.1) | 75–84: 20.3 (13.9–28.0) | |||||||||||

| ≥ 85: 25.0 (7.7–42.3) | ≥ 85: 33.3 (15.6–55.3) | |||||||||||

| Congo | ||||||||||||

| Guerchet et al.24 | 2010 | Brazzaville | Urban | 520 | ≥ 65 | 6.7 (4.7–9.2) | 65–74: 4.4 (2.3–7.5) | 18.8 (15.6–22.5)a | 65–74: 11.3 (7.8–15.7) | |||

| 75–84: 7.4 (4.2–11.9) | 75–84: 27.1 (21.1–33.8) | |||||||||||

| ≥ 85: 18.6 (8.4–33.4) | ≥ 85: 27.9 (15.3–43.7) | |||||||||||

| Nigeria | ||||||||||||

| Yusuf et al.28 | 2011 | Zaria | Rural | 322 | ≥ 65 | 2.8 (1.0–4.58) | 65–79: 2.0 (1.04–2.96) | – | – | |||

| Uwakwe et al.29 | 2009 | Dunukofia | Rural | 914 | ≥ 65 | – | – | 11.8 and 9.9b | – | |||

| Gureje et al.30 | 2006 | Ibadan | Rural and urban | 1904 | ≥ 65 | 10.1 (8.6–11.8) | 65–69: 7.2 (5.5–9.4) | – | – | |||

| 70–74: 7.7 (4.7–12.2) | ||||||||||||

| 75–79: 10.7 (7.3–15.4) | ||||||||||||

| ≥ 80: 20.9 (16.7–26.0) | ||||||||||||

| Ochayi et al.31 | 2006 | Jos | Rural and urban | 280 | ≥ 65 | 6.4 (3.8–9.9) | 65–74: 5.2 | – | – | |||

| 75–84: 5.9 | ||||||||||||

| 85–94: 14.0 | ||||||||||||

| ≥ 95: 12 | ||||||||||||

| Baiyewu et al.32 | 2002 | Ibadan | Rural and urban | 2487 | ≥ 65 | – | – | 6.3a | – | |||

| Uwakwe33 | 2000 | Uwan | Rural | 164 | ≥ 60 | 0c | – | – | – | |||

| Ogunniyi et al. and others12,15,16,18–23 | 1995–2006 | Ibadan | Rural and urban | 2494 | ≥ 65 | 2.3 (1.17–3.41) | 65–74: 0.86 | – | – | |||

| 75–84: 2.72 | ||||||||||||

| ≥ 85: 9.59 | ||||||||||||

CI, confidence interval.

a Data are for cognitive impairment with no dementia.

b Data are for participants with impairment detected by 1 memory test and ≥ 2 tests, respectively.

c Thirty-four (20.75%) were forgetful.

Note: In all 11 studies increasing age was associated with an increasing prevalence of both dementia and cognitive impairment. Five studies found a higher prevalence of dementia in women.12,24,30,31

Three studies reported the prevalences of both cognitive impairment and dementia, with data for 1518 participants analysed.24,26 Five studies reported only the prevalence of dementia12,15,16,18–23,28,30,31,33 and three reported only the prevalence of cognitive impairment, with data for 5164 and 4097 participants, respectively, analysed.27,29,32

Table 2 shows the cognitive screening tools and diagnostic processes used in the studies and indicators of the methodological quality are shown in Table 3. Only three studies documented evidence that confirmed the reliability of the tools.12,15,16,18–23,30,32 Three studies did not report confidence intervals (or information necessary to calculate them)27,29,32 and one did not report a confidence interval but provided enough information for this to be calculated.33 One study did not document sufficient information regarding appropriate probability sampling.29 One study documented uncertainties regarding cultural validity of the screening tools.27

Table 2. Screening tools and diagnostic criteria used in studies obtained from a systematic review of the literature on the prevalences of dementia and cognitive impairment in sub-Saharan Africa.

| Country, reference | Screening tools | Diagnostic criteria for dementia | Diagnostic criteria for cognitive impairment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benin | |||

| Guerchet et al.26 | CSI-D, SCEB, Clinical asst | Individuals with poor performances on the CSI-D or 5-Word Test underwent a structured interview by a senior neurologist with a Fon translator. The interview included a description and assessment of cognitive symptoms, activities of daily living, and social habits; a medical history; and a clinical examination. Additional cognitive tests included the oral Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test, Zazzo’s Cancellation Task and Isaac’s Set Test of Verbal Fluency. The diagnosis of dementia was made according to DSM-IV criteria and clinical criteria proposed by the NINCDS-ADRDA II for Alzheimer disease. Other types of dementia that were diagnosed were based on a history of stroke and other clinical features. | The CSI-D was used because of the low literacy level and three tests from the SCEB were used: the temporal orientation test, 5-Word Test and the semantic verbal fluency task (the clock-drawing test was not included). A questionnaire was used to obtain medical history and screening tools were administered to people > 65 years. Because of the high illiteracy rate, 30 was the highest score for the CSI-D (the test assessing praxias was used; current year and informant sections were excluded). Cognitive impairment was defined as either poor performance on the CSI-D (< 25.5 correct items of 30 tested) or the 5-Word Test (< 10 of 10). |

| Botswana | |||

| Clausen et al.27 | MMSE | Not applicable | Face-to-face interviews with questionnaires and a standardized clinical examination were used. A culturally adapted version of the MMSE (not validated) was used to account for education level. Items requiring writing and reading skills and geometric figures were omitted. Some items were slightly altered to adapt to local contexts. Cognitive impairment was defined as a score of < 16 correct items of 26 tested. |

| Central African Republic and the Congo | |||

| Guerchet et al.24 | CSI-D, 5-Word Test, DSM-IV, NINCDS-ADRDA II | Subjects with suspected dementia underwent a neurological examination and psychometrical tests, including the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test, Zazzo’s Cancellation Task and Isaac’s Set Test of Verbal Fluency. The diagnosis of dementia was made according to DSM-IV criteria and clinical criteria proposed by the NINCDS-ADRDA II for Alzheimer disease. Vascular dementia was diagnosed on the basis of the Hachinski scale. | Subjects aged > 65 years were interviewed by trained field investigators and instruments and scales (the CSI-D and 5-Word Test) were presented in local languages. Subjects with a poor performance on the CSI-D (< 25.5 correct items of 30 tested) or the 5-Word Test (< 10 of 10) were classified as having cognitive impairment or suspected dementia and invited to undergo clinical assessment by a neurologist. |

| Nigeria | |||

| Yusuf et al.28 | CSI-D, CERAD, BDS, Clinical asst | Screening instruments were translated into Hausa and all researchers were trained in the use of instruments. The Boston Naming Test and the Constructional Praxis Test from the CERAD were omitted and replaced by the stick design test. A pilot study was conducted. All subjects were interviewed in Hausa and underwent physical examination. The diagnosis of dementia was based on diagnostic criteria in both the ICD-10 (vascular dementia) and the DSM-IV (Alzheimer disease) and was confirmed by consensus (two physicians). | Not applicable |

| Uwakwe et al.29 | CSI-D, 10-WDRT | Not applicable | The full 10/66 Dementia Research Groups survey protocol, including ascertainment of cognitive impairment, was administered. Interviews comprised cognitive testing, a clinical interview, collection of data on health behaviour and service use and an informant interview. Cognition was assessed by CSI-D–associated memory items and by a 10-Word List to determine the level of immediate and delayed recall, for which an impaired score was defined as 1.5 standard deviations below the age- and education-specific norm. |

| Gureje et al.30 | 10-WDRT | Trained research interviewers conducted face-to-face interviews with selected people fluent in Yoruba. Quality control measures were used. Cognition was assessed using an adapted version of the 10-WDRT. This tool was used to diagnose probable dementia (a test-retest study of a smaller sample was conducted and showed good reliability). | Not applicable |

| Ochayi et al.31 | CSI-D, DSM-IV | Individuals were interviewed by study investigators, using the CSI-D. When necessary, a family member provided supplementary information. Dementia was defined as a CSI-D score < 28.5 (as in the Ibadan study and it was cross-culturally validated). | Not applicable |

| Baiyewu et al.32 | CSI-D, Clinical asst, CERAD | Not applicable | Residents were screened with the CSI-D. Cut-off scores were used to classify subjects as having a low, medium or high probability of dementia and to inform further clinical screening. All subjects with a high probability of dementia (those with a low CSI-D score), 50% with a medium probability of dementia (those with a borderline CSI-D score) and 5% with a low probability of dementia (those with a high CSI-D score) were selected for the clinical assessment phase (i.e. physician examination, informant interview, cognitive assessment and laboratory and imaging studies). Participants were assessed with the CERAD neuropsychological battery, which includes the MMSE, Word List Learning, the Animal Fluency Test, the Boston Naming Test and Constructional Praxis. A consensus diagnostic conference involving experienced clinicians confirmed each diagnosis. The criteria for CIND were as follows: the informant reported a decline in the subject’s cognition level, a physician detected impairment in the subject’s cognition level and/or the subject’s cognitive test score(s) were below approximately the seventh percentile; and the subject had no impairment in daily living tasks. Subtypes of CIND were assigned on the basis of presumed etiology. The criteria for CIND were comparable with those defined by the World Health Organization. |

| Uwakwe33 | SRQ-24, GMS | Participants aged > 60 years were interviewed with the SRQ-24 and GMS. A cut-off score of 5 was used for the SRQ-24 (validated and used in previous Nigerian studies). Validation of the GMS occurred only by means of pilot testing, after which 8 questions were reworded or modified. An open health interviewing booklet was used during the GMS interview. Clinical details were assessed by two senior psychiatrists and re-evaluated by a professor of psychiatry. ICD-10 criteria were used to diagnose dementia. | Not applicable |

| Ogunniyi et al. and others12,15,16,18–23 | CSI-D, Clinical asst, CERAD | Trained interviewers administered the CSI-D (pilot tested and validated). A discriminant function score was derived (perfect score, 33). Subjects were divided into three performance groups (good, intermediate and poor) on the basis of their discriminant function score, after which 5% of good performers, 50% of intermediate performers and all poor performers were selected for clinical assessment (a structured interview with an informant of the subject, focusing on cognitive functions, activities of daily living, social habits and past and current medical history). Each subject underwent detailed neuropsychological testing, followed by clinical examination and relevant laboratory tests, including computed tomography of the brain. A consensus diagnosis was made first on site and later blindly, from other sites. The diagnosis of dementia subtypes was based on clinical findings and accorded with ICD-10 and NINCDS-ADRDA II criteria. | Not applicable |

BDS, Blessed Dementia Rating Scale; CERAD, Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer Disease; CIND, cognitive impairment, no dementia; Clinical asst, Clinical Assessment; CSI-D, Community Screening Interview for Dementia; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Revision; GMS, Geriatric Mental State Schedule; ICD-10, International Classification of Infectious Diseases, Tenth Revision; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; NINCDS-ADRDA II, National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorder and Stroke and the Alzheimer Disease and Related Disorders Association II; SCEB, Short Cognitive Evaluation Battery; SRQ-24, Self-Reporting Questionnaire; 10-WDRT, 10-Word Delay Recall Test.

Table 3. Methodological quality of and validity scores for studies obtained from a systematic review of the literature on the prevalences of dementia and cognitive impairment in sub-Saharan Africa.

| Country, reference | Validity scoring criterion |

Validity score, out of 7 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target population well defined | Probability sampling used | Sample matched target population | Data collection method standardized | Tool valid | Tool reliable | Analysis included 95% CI | ||

| Benin | ||||||||

| Guerchet et al. 200926 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NK | Yes | 6 |

| Botswana | ||||||||

| Clausen et al. 200527 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | NK | No | 4 |

| Central African Republic | ||||||||

| Guerchet et al. 201024 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NK | Yes | 6 |

| Congo | ||||||||

| Guerchet et al. 201024 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NK | Yes | 6 |

| Nigeria | ||||||||

| Yusuf et al. 201128 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NK | Yes | 6 |

| Uwakwe et al. 200929 | Yes | NK | Yes | Yes | Yes | NK | No | 4 |

| Gureje et al. 200630 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| Ochayi et al. 200631 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NK | Yes | 6 |

| Baiyewu at al 200232 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 7 |

| Uwakwe 200033 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NK | No | 5 |

| Ogunniyi et al. and others12,15,16,18–23 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 |

CI, confidence interval; NK, not known.

Dementia prevalence

Benin

A study from Djidja, a rural area, included 502 participants and reported a prevalence of 2.6% (Table 1).26 The Community Screening Interview for Dementia (CSI-D) was used for detection of dementia. Diagnosis was confirmed by clinical assessment and participant-based interview; clinical dementia was diagnosed according to DSM-IV criteria and probable or possible Alzheimer disease was based on National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer Disease and Related Disorders Association II (NINCDS-ADRDA II) criteria. Analysis on the basis of dementia subtype revealed that the prevalence of Alzheimer disease was 2.2% and accounted for 53.8% of dementia diagnoses in this population, while vascular dementia contributed 7.7%. A further 30% of dementia cases were documented as possible dementia.

Central African Republic and Congo

The dementia prevalence was 8.1% among 496 participants in a rural region of Bangui, Central African Republic, and 6.7% among 520 participants from an urban region in Brazzaville, Congo.24 Cognitive screening was performed using the CSI-D and 5-Word Test, adapted and presented in local languages. Diagnosis was confirmed by neurological examination and further psychometric testing in participants suspected of dementia (defined as a CSI-D score of < 25.5 of 30 or a 5-Word Test score of < 10 of 10).

Both studies measured the prevalence of dementia subtypes. According to findings of neurological examinations, 82.5% of participants with dementia in Bangui had probable Alzheimer disease and 17.5% had vascular dementia, while in Brazzaville the proportions were 68.6% and 31.4%, respectively.

Nigeria

Five studies reported prevalence data for dementia. A small study of 322 participants conducted in rural Zaria used a battery of cognitive tests similar to that used in the 1995 study from Ibadan described below and reported a prevalence of 2.8%.28 Two studies from Ibadan were of a similar size but conducted approximately 10 years apart. These reported prevalences of 2.3% in 1995 and 10.1% in 2006. Differences between the studies included use of a single validated screening tool, the adapted 10-Word Delay Recall Test (10-WDRT), to define probable dementia in the 2006 study30 and a combination of screening tools (including the 10-WDRT) and clinical assessment, to define dementia in the 1995 study.12,15,16,18–23 The 2006 study also covered a wider region, including rural areas, while the earlier study was conducted in an inner-city region.

A study from Jos, in central Nigeria, reported a prevalence of 6.4% among 280 participants.31 This study used the CSI-D but there was no clinical assessment to confirm the diagnosis. A small study of 164 participants aged 60 years or older conducted in Uwan described common mental disorders. No cases of dementia were found. This study used the Self-Reporting Questionnaire (SRQ-24) and the Geriatric Mental State Schedule (GMS) as screening tools but the GMS had not been validated in Nigeria.33

Two studies examined subtypes of dementia. Yusuf et al. confirmed clinical cases of dementia based on the fulfilment of diagnostic criteria in both the International classification of diseases, tenth revision (ICD-10), and the Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth revision (DSM-IV). DSM-IV criteria were then used to diagnose Alzheimer disease and ICD-10 criteria were used to diagnose vascular dementia.28 Clinical criteria were used to diagnose other subtypes. The prevalence of Alzheimer disease was 1.9%, which accounted for six of the nine participants with dementia; of the remaining three, two had vascular dementia and one had fronto-temporal dementia. Among patients with dementia in the study from Ibadan, Alzheimer disease was diagnosed in 64.3% and vascular dementia was diagnosed in 28.6%.12 Clinical diagnoses were confirmed using DSM-IV, ICD-10 and clinical criteria developed by the NINCDS-ADRDA II.

Cognitive impairment prevalence

Benin

In a study of 502 participants in the rural community of Djidja, researchers adapted the cognitive section of the CSI-D to allow for a lack of temporal orientation and a high rate of illiteracy, such that a score of 30 (rather than 33) was the highest possible (Table 1). The researchers also had considerable difficulties in identifying informants to complete the informant section of the CSI-D and therefore adapted the criteria for cognitive impairment. Cognitive impairment was defined as a poor performance in the CSI-D cognitive section (defined as a score of < 25.5 out of 30) or a poor performance on the 5-Word Test. Use of this adjusted instrument revealed a prevalence of cognitive impairment with no dementia (CIND) of 10.4%.26

Botswana

Researchers screened 372 participants aged ≥ 60 years for several chronic diseases. Cognitive impairment was assessed using an adapted but non-validated version of the Mini–Mental State Examination (MMSE), which omitted sections that required writing or reading and adapted other sections to the local context. A 9% prevalence of cognitive impairment was reported without measures of uncertainty, with no distinction made between cognitive impairment with or without dementia.27

Central African Republic and Congo

Studies conducted in Bangui and Brazzaville reported CIND prevalences of 25% and 18.8%, respectively.24

Nigeria

A study from Dunukofia screened 914 participants with three memory tests (CSI-D and 10-word immediate and delayed recall). A total of 11.8% of participants had just one memory test indicating cognitive impairment, whereas cognitive impairment was detected in 9.9% by two or more memory tests.29

A study from Uwan, described above, used the SRQ-24 and the GMS to screen 164 participants older than 60 years and 34 (20.7%) reported forgetfulness, which may have been indicative of cognitive impairment.33

The Ibadan study group also studied cognitive impairment in 2000 in both rural and urban regions. They found a CIND prevalence of 6.3% among 2487 participants who were screened using the CSI-D tool and were assessed clinically. The sample used for this study included some of the participants in the 1995 study of dementia described above, as well as additional participants. The study also followed up 87 of the 152 patients with CIND and found that after 2 years 16.1% had developed dementia, 58.6% still had a diagnosis of CIND and 25.3% had normal cognitive function.32

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of the prevalence of dementia and cognitive impairment in older populations in sub-Saharan Africa. Eleven studies were identified and all had a cross-sectional design. Prevalences varied widely between countries and by publication date. The predominant factors associated with a higher prevalence of dementia were older age and female sex. Older age was strongly associated with dementia and cognitive impairment in all studies and similar associations have been reported globally.34 Female sex was a risk factor for both outcomes in five studies12,24,30,31 and has been confirmed in many international studies.34 The majority of studies were from Nigeria and western and central Africa, with only one from southern Africa and none from eastern Africa. We are aware of another study currently being conducted in a rural community of 2000 households in Bloemfontein, South Africa, but to date only a pilot study has been completed, with prevalence of 6.4% for dementia diagnosed by DSM-IV criteria.35

These studies have several limitations. Dementia involves a change in function and cognition but in a cross-sectional study such change is difficult to determine and assessment is reliant on the reports of individuals close to the individual. Survivor bias may have influenced prevalence data for both dementia and cognitive impairment, since individuals who are more vulnerable to cognitive impairment and poor health would be less likely to survive into old age in sub-Saharan Africa.

The generalizability of these studies is also limited. The more recent estimates of dementia prevalence remain lower than those reported in Europe (6.2%; 4% for Alzheimer disease) and the United States of America (8%; 6% for Alzheimer disease),11,13–16 but this comparison is flawed because the age structure of the population older than 65 years in sub-Saharan Africa and Europe will differ. In sub-Saharan Africa, there is a higher proportion of individuals aged 66–80 years and a smaller proportion aged 81 years and older, leading to a lower overall prevalence of dementia, which is predominantly a disease of older people. Cognitive impairment prevalences of 3% to 19% among people older than 65 years in other parts of the world (range: 3–19%) are comparable with those reported by studies in our review.36 Studies of migrant African origin populations now living in Europe or North America have reported higher prevalences of cognitive impairment (range: 8–34%) but the majority of these studies included African-Caribbean participants or did not clearly distinguish the ethnic origins of study subjects. 37,38 Further research of first-generation sub-Saharan Africa migrant populations may provide more accurate data and insight into environmental factors associated with dementia.

There are challenges to assessing cognitive change and mental health in sub-Saharan Africa. Social impairment is not as highly associated with cognitive impairment in African communities, compared with communities in developed countries. The social functions and participation of elderly individuals in African culture differ from those found in Western cultures and factors associated with normal functioning in old people also differ.32 This may be because the DSM-IV and ICD-10 screening instruments require certain levels of social impairment to confirm clinical dementia and thus may lead to under-diagnosis in sub-Saharan Africa. The move from participant-based to informant-based cognitive tests has the potential to diminish the effects of education level and cultural biases because the informant reports direct changes in cognition on the basis of their knowledge of the subject’s prior cognitive and functional status. The CSI-D combines both approaches and incorporates a direct cognitive assessment and it has been accepted as a culturally adaptable screening tool in some African countries. Further development and refinement of the CSI-D is needed and future studies of prevalence should use this or some other validated screening tool. The 10/66 Dementia Research Group has developed evidence-based diagnostic tools that would facilitate inter-cultural research.39

Large cross-sectional surveys in both rural and urban populations from more countries in sub-Saharan Africa would aid health-care planning. Longitudinal studies examining incidence and predictors and factors modifying the rate and severity of cognitive decline specific to populations in this region are also needed. Qualitative analyses investigating cultural perceptions of dementia from the perspectives of the community, caregivers and individuals with dementia would offer insight into access issues and improvements in health care.

While still experiencing high mortality and fertility rates and heavily burdened by infectious disease, the population of sub-Saharan Africa is ageing and a rise in noncommunicable chronic diseases is inevitable. With no known cure or preventative intervention, dementia and cognitive impairment are set to be one of the biggest public health challenges in sub-Saharan Africa in the 21st century.

Acknowledgements

We thank Karen Rees for her assistance with statistical methods. Margaret Thorogood is also affiliated with Warwick Medical School, University of Warwick.

Funding:

AM held an Academic Clinical Fellowship post which was funded by the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the United Kingdom National Health Service, the NIHR or the United Kingdom Department of Health. The sponsor had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.The world health report: primary health care now more than ever Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008.

- 2.The global burden of disease: 2004 update Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Ageing-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7:270–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mathers CD, Loncar D. Updated projections of global mortality and burden of disease, 2002-2030: data sources, methods and results Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005 (Evidence and Information for Policy Working Paper).

- 5.Ineichen B. The epidemiology of dementia in Africa: a review. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:1673–7. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00392-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferri CP, Prince M, Brayne C, Brodaty H, Fratiglioni L, Ganguli M, et al. Alzheimer’s Disease International Global prevalence of dementia: a Delphi consensus study. Lancet. 2005;366:2112–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67889-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World population ageing 2009 New York: United Nations; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dementia: a public health priority Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garrett MJ. Health futures: a handbook for health professionals Geneva: World Health Organization; 1999.

- 10.Kalaria RN, Maestre GE, Arizaga R, Friedland RP, Galasko D, Hall K, et al. World Federation of Neurology Dementia Research Group Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia in developing countries: prevalence, management, and risk factors. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:812–26. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70169-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Alzheimer report 2009 London: Alzheimer’s Disease International; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ogunniyi A, Gureje O, Baiyewu O, Unverzagt F, Hall KS, Oluwole S, et al. Profile of dementia in a Nigerian community–types, pattern of impairment, and severity rating. J Natl Med Assoc. 1997;89:392–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lobo A, Launer LJ, Fratiglioni L, Andersen K, Di Carlo A, Breteler MM, et al. Neurologic Diseases in the Elderly Research Group Prevalence of dementia and major subtypes in Europe: a collaborative study of population-based cohorts. Neurology. 2000;54(Suppl 5):S4–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hendrie HC, Ogunniyi A, Hall KS, Baiyewu O, Unverzagt FW, Gureje O, et al. Incidence of dementia and Alzheimer disease in 2 communities: Yoruba residing in Ibadan, Nigeria, and African Americans residing in Indianapolis, Indiana. JAMA. 2001;285:739–47. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.6.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogunniyi A, Baiyewu O, Gureje O, Hall KS, Unverzagt F, Siu SH, et al. Epidemiology of dementia in Nigeria: results from the Indianapolis-Ibadan study. Eur J Neurol. 2000;7:485–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2000.00124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hendrie HC, Osuntokun BO, Hall KS, Ogunniyi AO, Hui SL, Unverzagt FW, et al. Prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia in two communities: Nigerian Africans and African Americans. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1485–92. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.10.1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall K, Gureje O, Gao S, Ogunniyi A, Hui SL, Baiyewu O, et al. Risk factors and Alzheimer’s disease: a comparative study of two communities. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1998;32:698–706. doi: 10.3109/00048679809113126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perkins AJ, Hui SL, Ogunniyi A, Gureje O, Baiyewu O, Unverzagt FW, et al. Risk of mortality for dementia in a developing country: the Yoruba in Nigeria. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17:566–73. doi: 10.1002/gps.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen J, Gao S, Unverzagt FW, Ogunniyi A, Baiyewu O, Gureje O, et al. Validation analysis of informant’s ratings of cognitive function in African Americans and Nigerians. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21:618–25. doi: 10.1002/gps.1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hall KS, Gao S, Emsley CL, Ogunniyi AO, Morgan O, Hendrie HC. Community screening interview for dementia (CSI ‘D’); performance in five disparate study sites. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15:521–31. doi: 10.1002/1099-1166(200006)15:6<521::AID-GPS182>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hall KS, Ogunniyi AO, Hendrie HC, Osuntokun B, Hui SIUL, Musick B, et al. A cross-cultural community based study of dementias: Methods and performance of the survey instrument Indianapolis, USA, and Ibadan, Nigeria. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 1996;6:129–42. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1234-988X(199610)6:3<129::AID-MPR164>3.3.CO;2-A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hall KS, Murrell J, Ogunniyi A, Deeg M, Baiyewu O, Gao S, et al. Cholesterol, APOE genotype, and Alzheimer disease: an epidemiologic study of Nigerian Yoruba. Neurology. 2006;66:223–7. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000194507.39504.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guerchet M, M’belesso P, Mouanga AM, Bandzouzi B, Tabo A, Houinato DS, et al. Prevalence of dementia in elderly living in two cities of Central Africa: the EDAC survey. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2010;30:261–8. doi: 10.1159/000320247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boyle MH. Guidelines for evaluating prevalence studies. Evid Based Ment Health. 1998;1:37–9. doi: 10.1136/ebmh.1.2.37. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guerchet M.Houinato D, Paraiso MN, von Ahsen N, Nubukpo P, Otto Met al. Cognitive impairment and dementia in elderly people living in rural Benin, West Africa. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 20092734–41. 10.1159/000188661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clausen T, Romoren M. Chronic disease in Botswana. J Ageing. 2005;9:455–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yusuf AJ, Baiyewu O, Sheikh TL, Shehu AU. Prevalence of dementia and dementia subtypes among community-dwelling elderly people in northern Nigeria. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23:379–86. doi: 10.1017/S1041610210001158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uwakwe R, Ibeh CC, Modebe AI, Bo E, Ezeama N, Njelita I, et al. The epidemiology of dependence in older people in Nigeria: prevalence, determinants, informal care, and health service utilization. A 10/66 dementia research group cross-sectional survey. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1620–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gureje O, Ogunniyi A, Kola L. The profile and impact of probable dementia in a sub-Saharan African community: results from the Ibadan Study of Aging. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61:327–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ochayi B, Thacher TD. Risk factors for dementia in central Nigeria. Aging Ment Health. 2006;10:616–20. doi: 10.1080/13607860600736182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baiyewu O, Unverzagt FW, Ogunniyi A, Hall KS, Gureje O, Gao S, et al. Cognitive impairment in community-dwelling older Nigerians: clinical correlates and stability of diagnosis. Eur J Neurol. 2002;9:573–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2002.00434.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Uwakwe R. The pattern of psychiatric disorders among the aged in a selected community in Nigeria. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15:355–62. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1166(200004)15:4<355::AID-GPS126>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Borenstein AR, Copenhaver CI, Mortimer JA. Early-life risk factors for Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20:63–72. doi: 10.1097/01.wad.0000201854.62116.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Der Poel R, Heyns M. Prevalence of dementia in central South Africa. Program and abstracts of the 26th International Conference of Alzheimer’s Disease International Toronto: Alzheimer’s Disease International; 2011:120. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gauthier S, Reisberg B, Zaudig M, Petersen RC, Ritchie K, Broich K, et al. International Psychogeriatric Association Expert Conference on mild cognitive impairment Mild cognitive impairment. Lancet. 2006;367:1262–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68542-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adelman S, Blanchard M, Livingston G. A systematic review of the prevalence of and covariates of dementia or relative cognitive impairment in the older African-Caribbean population in Britain. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24:657–65. doi: 10.1002/gps.2186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Demirovic J, Prineas R, Loewenstein D, Bean J, Duara R, Sevush S, et al. Prevalence of dementia in three ethnic groups: the South Florida program on aging and health. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13:472–8. doi: 10.1016/S1047-2797(02)00437-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prince M, Acosta D, Chiu H, Scazufca M, Varghese M, 10/66 Dementia Research Group Dementia diagnosis in developing countries: a cross-cultural validation study. Lancet. 2003;361:909–17. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12772-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]