Hybrid battery derives energy from waste water

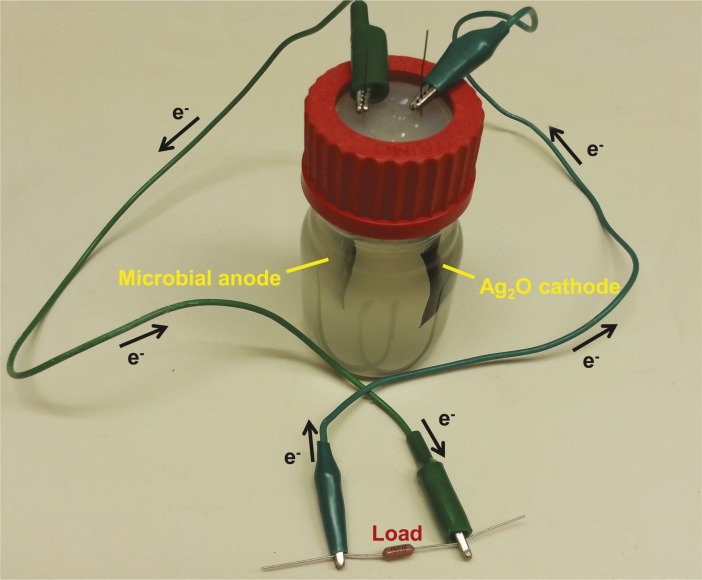

Hybrid battery device.

Wastewater might seem an unlikely energy reservoir for power production, but Xing Xie et al. (pp. 15925–15930) have created a hybrid battery device that derives energy from wastewater. At the battery’s anode, microorganisms oxidize organic matter that has accumulated in the water, releasing electrons. The electrons pass through an external circuit, where they are available for use as electrical energy, and then return to a solid-state electrode within the battery. Once the electrode has filled with electrons, the user can remove and recharge the spent portion by exposing it to oxygen. Power production resumes immediately after reinstallation. The authors’ design boosts efficiency by preventing microorganism exposure to oxygen and allowing electrode reoxidation under favorable conditions, rather than through a typical ion-exchange membrane. The authors report a net efficiency of about 30%, on par with the best commercial solar cells. According to the authors, low-cost materials are required for these devices to become attractive for large-scale use, but the results demonstrate that the microbial battery concept can safely and efficiently turn “waste” organic matter into usable energy. — J.M.

Intravaginal ring protects macaques against simian HIV

Preliminary studies have indicated that topical application of the antiretroviral drug tenofovir may be a promising approach to prevent sexual transmission of HIV. However, recent clinical trials demonstrated that a vaginal gel containing tenofovir was ineffective in preventing HIV infection, in part due to the study participants’ difficulty in adhering to frequent dosing. To overcome these challenges, James Smith et al (pp. 16145–16150) developed an intravaginal ring (IVR) that continuously released protective levels of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF)—which is 100 times more potent than tenofovir against HIV in vitro—over the course of 28 days in pigtailed macaques. The authors found that all six of the animals that were treated with the IVR, which was changed every 4 weeks, remained virus-free after 16 weekly vaginal exposures to simian-HIV, a virus containing genes from HIV and its primate equivalent, SIV. By contrast, 11 of the 12 untreated animals became infected after approximately 4 viral exposures. The vaginal secretions of the treated animals displayed elevated levels of the drug throughout the 4-month treatment period, and effectively prevented HIV infection of human cells grown in culture. The authors suggest that an IVR that continuously releases TDF may be an effective tool to prevent sexual transmission of HIV in humans. — N.Z.

Bats harbor potential ancestor of human hepatitis B virus

Tent-making bats (Uroderma bilobatum) roosting under a large leaf modified by the bats to provide a tent-like shelter. Bocas del Toro Province, Panama.

More than 240 million people worldwide are chronically infected with hepatitis B, which kills an estimated 620,000 people every year. The high efficacy of a prophylactic vaccine against the disease and the lack of established animal reservoirs for the virus underlie hopes to eradicate the disease in the coming decades. Jan Drexler et al. (pp. 16151–16156) report the discovery of three novel virus species closely related to hepatitis B virus (HBV) in bats, whose longevity, dense roosting communities, and migration facilitate the evolution and transmission of pathogenic viruses. The authors used molecular and immunological assays to screen 54 species of bats from Panama, Brazil, Gabon, Ghana, Germany, Papua New Guinea, and Australia, and identified three HBV-related virus species, namely roundleaf bat HBV, horseshoe bat HBV, and tent-making bat HBV (TBHBV). The authors report that the bat infection patterns resembled human hepatitis, and virus particles engineered to bear surface proteins from TBHBV could successfully infect cultured human liver cells, in contrast to the two other distantly related bat viruses. However, antisera from humans successfully vaccinated against HBV failed to block the infection of cultured human liver cells. According to the authors, TBHBV might be related to the common ancestor of HBV and primate HBV-like viruses, and global hepatitis B eradication efforts might require vaccine formulations with broad antigenicity. — P.N.

Thyroid hormone regulates heat loss via vascular controls

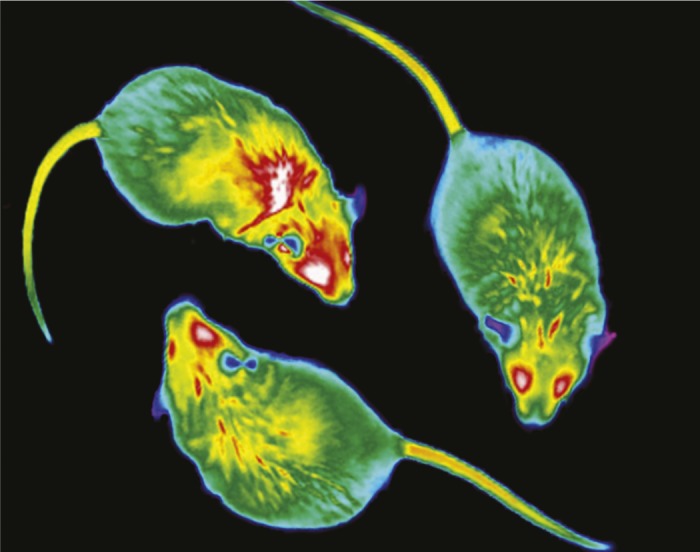

Infrared thermography allows accurate heat dissipation analysis in conscious test mice.

Thyroid hormone helps regulate energy metabolism, body temperature, and cardiovascular function. Patients with thyroid disease often experience an increased sensitivity to environmental temperature, a symptom typically attributed to the role of thyroid hormone in basal metabolism. Amy Warner et al. (pp. 16241–16246) report a previously unrecognized connection between cardiovascular regulation and metabolic activity that questions current hypotheses about the role of thyroid hormone in thermogenesis. Using infrared thermography on conscious mice, the authors demonstrated that a point mutation in thyroid hormone receptor α1 affects the animals’ ability to regulate body temperature via tail arteries, in turn activating brown adipose tissue metabolism to generate heat and maintain body temperature. Furthermore, reversing the defect reestablished appropriate vasoconstrictive heat regulation over the tail surface and normalized brown fat activity and energy expenditure. The findings demonstrate that thyroid hormone influences vascular heat conservation and dissipation, adding a previously unreported role for the hormone in thermoregulation. In addition, the connection between vascular function and energy expenditure in mice may help explain metabolic dysregulation in humans with nonthyroidal illnesses that impede thyroid hormone signaling such as sepsis and certain cancers, according to the authors. — T.J.

Functional MERS coronavirus clone

Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), a recently detected group 2c human betacoronavirus, has been linked to at least 94 confirmed cases and 46 deaths. The alarming mortality rate, combined with the virus’ confirmed mechanism of human-to-human transmission, has led to an urgent need for diagnostic tests, treatments, and vaccines. Trevor Scobey et al. (pp. 16157–16162) synthesized a panel of contiguous complementary DNAs, or cDNAs, spanning the virus’s entire genome and developed a cassette-based infectious cDNA clone of MERS-CoV. After rigorous tests to confirm that the clone functions similarly to wildtype MERS-CoV, with regards to replication, protein and RNA expression, and the processing of a structural component of coronaviruses known as spike protein, the authors conducted trials that show that the virus replicates preferentially in differentiated primary lung cells. In conjunction with recombinant viruses that express indicator proteins, the authors report, the availability of a MERS-CoV molecular clone might allow therapeutic compounds to be tested using rapid, high-throughput technologies and offers researchers a genetic platform to study coronavirus gene function and design live virus vaccines. — T.J.