Significance

Off-flavor substances generated naturally in foods/beverages deteriorate the quality of products considerably. Generally, it has been thought that off-flavor substances induce unpleasant smells exogenously. Here, however, we show that 2,4,6-trichroloanisole (TCA), known as one of the strongest off-flavors, inhibits ciliary transduction channels. Surprisingly, suppression was caused with 1-aM solution. The TCA effect showed slow kinetics, with an integration time of approximately 1 s, and positively correlated with the partition coefficient at octanol/water boundary (pH 7.4) of derivatives. These results indicate that the channels are inhibited through a partitioning of those substances into the lipid bilayer of plasma membranes. Furthermore, TCA was detected in varieties of foods/beverages surveyed for odor losses and is likely to be related to the reduction of flavor.

Keywords: olfactory masking, ion channel, patch-clamp

Abstract

We investigated the sensitivity of single olfactory receptor cells to 2,4,6-trichloroanisole (TCA), a compound known for causing cork taint in wines. Such off-flavors have been thought to originate from unpleasant odor qualities evoked by contaminants. However, we here show that TCA attenuates olfactory transduction by suppressing cyclic nucleotide-gated channels, without evoking odorant responses. Surprisingly, suppression was observed even at extremely low (i.e., attomolar) TCA concentrations. The high sensitivity to TCA was associated with temporal integration of the suppression effect. We confirmed that potent suppression by TCA and similar compounds was correlated with their lipophilicity, as quantified by the partition coefficient at octanol/water boundary (pH 7.4), suggesting that channel suppression is mediated by a partitioning of TCA into the lipid bilayer of plasma membranes. The rank order of suppression matched human recognition of off-flavors: TCA equivalent to 2,4,6-tribromoanisole, which is much greater than 2,4,6-trichlorophenol. Furthermore, TCA was detected in a wide variety of foods and beverages surveyed for odor losses. Our findings demonstrate a potential molecular mechanism for the reduction of flavor.

Throughout culinary history, consumers have been disturbed by naturally generated off-flavor substances that can greatly reduce the palatability of foods and beverages. Because off-flavors appear at very low concentrations of contaminants, chemical identification of responsible compounds has been limited. One of the most potent off-flavor compounds identified to date is 2,4,6-trichloroanisole (TCA), known specifically for inducing a cork taint in wines (1). In general, off-flavor compounds have been thought to induce unpleasant exogenous smells (2–9), and would therefore be expected to excite specific olfactory receptors (10) transducing malodors. However, we found that TCA did not generate excitatory responses in single olfactory receptor cells (ORCs), but potently suppressed cyclic nucleotide-gated (CNG) channels in these cells. Because CNG channels play a key role in olfactory transduction, suppression of these channels suggests a reduction of endogenous odors, rather than an addition of exogenous odors. Surprisingly, TCA exerted a much more potent suppressive effect on CNG channels (100–1,000-fold) than other known olfactory masking agents that have been widely used in perfumery. It was also more potent than a well-known CNG channel blocker, l-cis-diltiazem. We could account for such high suppressive potency in terms of temporal integration and slow recovery from suppression by TCA. The order of potency of CNG suppression by TCA analogues or precursors was identical to that of the human detection of the corresponding off-flavors, i.e., TCA equivalent to 2,4,6-tribromoanisole(TBA), which is much greater than 2,4,6-trichlorophenol (TCP; precursor of TCA), suggesting that cork taint is related to TCA suppression of CNG channels. We further confirmed that potent suppression was caused by a haloarene structure having a side chain that increases the partition coefficient at octanol/water boundary at pH 7.4 (LogD). The present findings not only reveal a likely mechanism of flavor loss, but also suggest certain molecular structures as possible olfactory masking agents and powerful channel blockers.

Results

Suppression by TCA of Odorant- and cAMP-Induced Currents in Single ORCs.

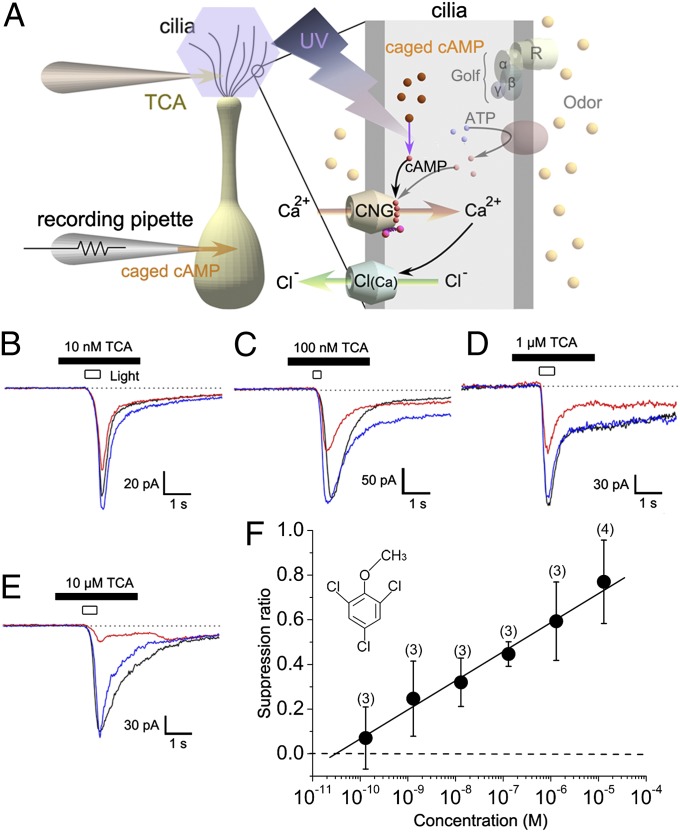

We examined the effects of TCA on ORCs in whole-cell electrophysiological recordings. Considering its low effective concentration for producing off-flavors, we expected TCA to elicit excitatory responses in ORCs at low concentrations or in a majority of cells. However, we did not detect any ORC responses to TCA application. Instead, we were surprised to find that TCA actually suppressed ORC transduction currents. To identify the mechanism underlying this effect, we activated CNG channels by photolysis of caged cAMP introduced into the cytoplasm of ORCs via the whole-cell pipette (Fig. 1A). In this experimental protocol, UV stimulation opens CNG channels directly, bypassing the transduction cascade upstream from adenylyl cyclase, and therefore enabled us to evaluate the effect of TCA on transduction channels. When 10 nM TCA was applied to a recorded cell by puffer pipette, the inward current induced by uncaging cytoplasmic cAMP was attenuated (Fig. 1B). As no excitatory current was observed in response to TCA puffing alone, it is unlikely that the reduction in cAMP-induced response was caused by adaptation of the olfactory transduction mechanism (11–14). Attenuation by 10 nM TCA was observed in all tested cells (N = 19; 1-μm diameter of puff pipette opening), consistent with suppression of a channel conductance (15) rather than inhibition via olfactory receptors (16). The inward current response induced by an odorant (1 mM cineole) was also suppressed by 1 μM TCA (Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

Suppression by TCA of cAMP-induced current. (A) Experimental scheme: whole-cell recording under voltage-clamp (holding potential of −50 mV in all experiments). AC, adenylyl cyclase; Golf, G protein; R, olfactory receptor protein. TCA was included in the puffer pipette at the concentration indicated in each panel, and applied to the cell by pressure ejection (50 kPa). Tip opening diameter of stimulus pipette was 1µm. Current suppression by 10 nM (B), 100 nM (C), 1 µM (D), and 10 µM (E) TCA. Control, black; drug, red; recovery, blue. Data were obtained from different cells. (F) Relation between TCA concentration and SR. Note that the concentrations indicated are the values in the puffer pipette, and the actual concentration at the cell must be much lower than these values. Numbers in parentheses indicate cells examined. Each plot shows the average value and SD.

Current suppression by TCA was concentration-dependent (Fig. 1 C–E). As the effect of TCA was not a simple channel blockade (as discussed later), the dose-suppression relation could not be fitted by a Michaelis–Menten or Hill equation. The relationship between suppression ratio (SR) and concentration was well fitted by a straight line when concentration was plotted on a logarithmic scale (Fig. 1F). ORC transduction currents are generated by sequential activation of CNG channels and Ca2+-activated Cl [Cl(Ca)] channels, with the latter contributing a large proportion of the total current (17–23). Suppression by TCA appears to target CNG channels, because we did not detect any TCA effects on Cl(Ca) channels activated directly by uncaging cytoplasmic Ca2+ (Fig. S2).

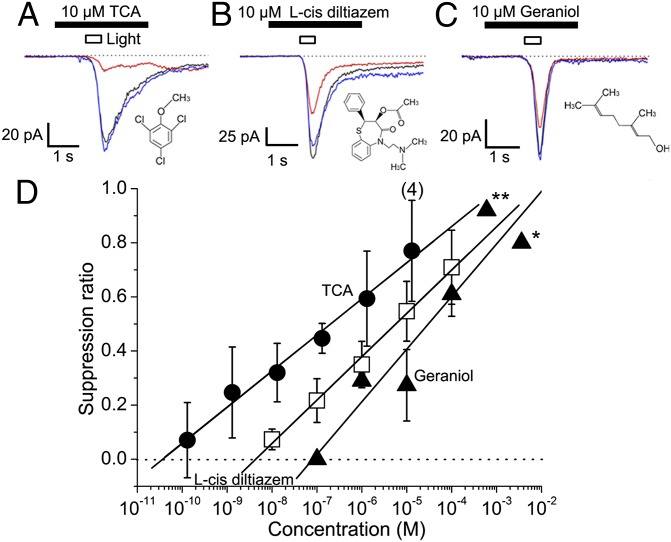

With the same experimental protocols, two other compounds were compared with TCA for their channel suppression effects (Fig. 2A). One was l-cis-diltiazem, a well-known blocking agent of the CNG channel (24). The other was geraniol, a strong olfactory masking agent used in perfumery, which has been shown to suppress the CNG channel (8). Both agents suppressed ORC currents induced by photolysis (Fig. 2 B and C), but the effects were much weaker compared with TCA. The EC50 values were 0.19 μM for TCA, 5.8 μM for l-cis-diltiazem, and 29 μM for geraniol (Fig. 2D; note that actual concentration at the cell was much lower). It seems likely that the TCA effect will also be stronger than for other drugs that have been shown to block the CNG channel (25). Thus, TCA may be a member of a new class of potent inhibitors of CNG channels.

Fig. 2.

Suppression of cAMP-induced response by TCA, l-cis-diltiazem (specific blocking agent), and geraniol (potent masking agent). (A) Suppression by 10 µM TCA. Traces: black, control; red, drug; blue, recovery. Drugs were applied from a puffer pipette with a diameter of 1 µm. Suppression by 10 µM l-cis-diltiazem (B), 10 µM geraniol (C), and dose-suppression relation (D). (*0.1% geraniol, **0.01% geraniol obtained data from ref. 8.) SR of TCA is indicated with filled circles, l-cis diltiazem by open squares; geraniol by filled triangles. Each plot shows the average value and SD obtained from three examined cells, except for 10 µM TCA (n = 4).

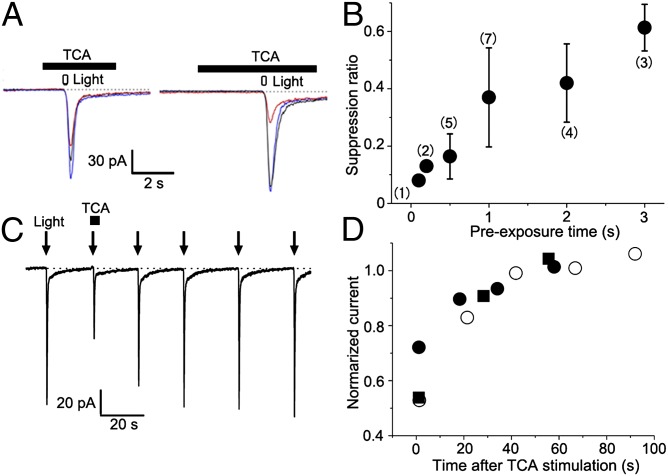

Least Effective Concentration.

So far, the TCA concentrations we have reported refer to solutions contained in the puffer pipettes. To better understand mechanism of suppression by TCA, it is important to estimate the effective concentration delivered to the ORC membrane. These are expected to be significantly lower, depending on the tip diameter of the puffer (Fig. S3). Furthermore, the degree of suppression was a function of TCA preexposure time (i.e., several seconds) before CNG channel activation by photolysis (Fig. 3 A and B), and recovery was relatively slow (50% recovery at approximately 10 s; Fig. 3 C and D). These time lags suggest that cumulative partitioning into the ciliary membrane may increase the concentration of TCA in the vicinity of CNG channels, thereby increasing their sensitivity to suppression.

Fig. 3.

Time-dependence of onset and offset of TCA suppression. (A) Onset time course of TCA suppression. (Left) Preexposure time was 1 s. Light indicates UV light stimulation. (Right) Preexposure time was 3 s. Data obtained from the same cell. Traces: black, control; red, 100 nM TCA; blue, recovery. (B) The suppression was plotted against the time of preexposure. Each plot shows the average value and SD. Numbers in parentheses indicate the cells examined. (C) Offset wave forms. (D) Time course of recovery. The recoveries from the current suppression by single stimulation of 1 μM TCA were plotted against the time after the odor stimulation (n = 3). Different symbols indicate data from different cells. Pipette diameter was 1 μm.

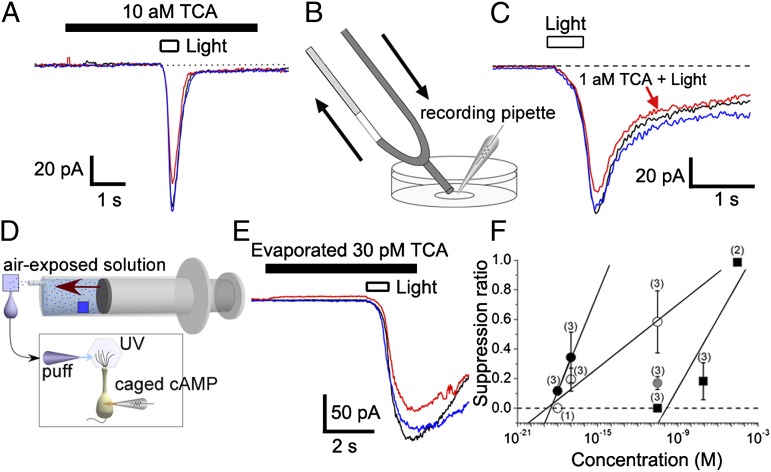

To estimate the minimal effective concentration, we determined the combination of pipette tip size and preexposure time for saturating responses, and then decreased the pipette concentration to find the smallest effective dose. For example, we detected a slight suppression when 10 aM TCA solution was applied to the cell with a puffer pipette with a tip diameter of 3.2 μm (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Least effective concentration of TCA. (A) An example showing the effect of 10 aM TCA in puffer pipette (tip opening diameter, 3.2 µm). TCA was applied for 6 s (beginning 3 s before UV light stimulation). Duration of light stimulation was 0.5 s. Traces: black, control; red, TCA; blue, recovery. (B) Schematic diagram of U-tube system. The diameter of the tip was ∼200 μm. (C) Effect of 1 aM TCA applied with a U-tube system. TCA application was conducted for ∼30 s, and duration of light stimulation was 0.5 s. (D) Schematic diagram of TCA application after evaporation. In this system, filter paper (1 cm × 1 cm, blue square) soaked in a solution containing 30 pM TCA was placed in a syringe, and TCA was allowed to evaporate for 15 min. The vapor was then applied at a rate of 50 mL over 5 s to a second piece of filter paper soaked in 40 µL of normal Ringer solution. (E) Effect of evaporated TCA (30 pM solution). (F) Dose-suppression relation. Plots: filled circles, TCA by U-tube application; open circles, TCA by pipette application (5 s, diameter of stimulus pipettes was 1 µm); gray circles, evaporated TCA by pipette application (5 s, diameter of stimulus pipettes was 1 µm); filled squares, geraniol by U-tube application. Note that geraniol application does not cause any response reduction at <10−10 M, excluding a possibility of dilution error in our protocols. Each plot shows the average value and SD.

We further applied TCA and other drugs with a U-tube system (26), by which the chemicals can be directly applied at more accurate concentrations (Fig. 4B). Surprisingly, we could detect a reduction in cAMP-induced current even when 1 aM TCA solution was applied (SR = 0.12 ± 0.02; three of three cells; Fig. 4C).

When we perceive contamination of wines by TCA, the contaminant evaporates from a solution phase and is then transported in gas phase by convection and diffusion (orthonasally or retronasally) to the olfactory epithelium, where only a small fraction of the molecules dissolve into the mucosa and reach ORCs. To determine if the concentration of TCA after such a transport process can suppress CNG channels, we mimicked the process by in vitro experiments (Fig. 4 D and E). A concentration of 30 pM TCA (detection threshold in humans; Table 1) in solution placed inside a syringe was evaporated into air, this air was applied to filter paper wetted with Ringer solution, and the Ringer solution was then squeezed out and used to stimulate cells (Fig. 4D; see also ref. 8). We found that this solution was able to suppress the CNG current (Fig. 4E). The concentration of TCA in the suppressive solution was measured in parallel by GC-MS. With 10 μM TCA in the syringe, the final suppressive solution contained ∼1 nM TCA, which is near the detection limit of GC-MS. Indeed, we could not detect any TCA by GC-MS when 1 μM was used as the source in the syringe. Therefore, the dilution factor was ∼104 fold, and 30 pM TCA in the original solution would yield ∼3 fM in the suppressive solution, which is still higher than the minimal effective concentration of TCA (10 aM with the puffer) we found for suppression of the CNG channel.

Table 1.

Numbers of correct judgments for off-flavor substances in triangle tests

| Substance/solvent | Concentration/judgments | ||

| TCA | 3 ppt (14 pM) | 10 ppt (47 pM) | 15 ppt (71 pM) |

| Red wine | 7 | 12* | — |

| White wine | 5 | 3 | 15* |

| TBA | 10 ppt (29 pM) | 30 ppt (87 pM) | 100 ppt (290 pM) |

| Red wine | 4 | 7 | 13* |

| White wine | 6 | 5 | 12* |

| TCP | 30 ppb (152 nM) | 100 ppb (506 nM) | 300 ppb (1,518 nM) |

| Red wine | 6 | 6 | 11* |

| White wine | 4 | 12* | — |

According to binominal tables, 11 or more correct judgments are significantly above chance at P < 0.05 (n = 20).

When dose-suppression relations obtained with U-tube experiments were plotted for geraniol and TCA, the threshold values (i.e., SR = 0) obtained by extrapolation were 150 pM and 0.3 aM, respectively (Fig. 4F). Thus, the effective concentration was much higher for geraniol than for TCA as expected, confirming the validity of our dilution protocol. In addition, it was confirmed that the low concentration effect was unique to TCA.

Reduction of Wine Odors by TCA and TBA.

Effects of TCA on wine flavor have long been reported. However, previous surveys were conducted in the context of TCA contributing additional odors (1). In the present study, we showed that TCA suppressed the olfactory transduction current. Therefore, we reexamined human olfactory perception to look for reductions in wine odor. In addition, we investigated the relative potency of odor reductions among TCA analogues or derivatives to compare against their CNG channel suppression properties (Channel Suppression by Related Substances and Correlation with Human Sensation).

Twenty panelists were asked to evaluate whether original odors of wines were reduced when they were contaminated by off-flavor substances. For evaluation, the triangle test that has been approved in Japanese Industrial Standards (JIS) Committee or British Standards Institution (BSI)/International Organization for Standardization (ISO) was used. The strongest reduction in odor was observed when wine was contaminated with TCA (Table 1). The off-flavor recognition thresholds were 47 pM (10 ppt) for red wine and 71 pM (15 ppt) for white wine. TBA also caused similar effects with slightly higher concentrations (290 pM for red and white wines; Table 1). Reduction of odor perception was also observed with TCP at concentrations four to five orders of magnitude higher (1.5 μM for red wine, 0.5 μM for white wine) than those of TCA or TBA (Table 1).

In another set of experiments, we also examined the concentration at which the musty odor of TCA was recognized in wine. In evaluation with white wines, the reduction of original odor and the extrinsic musty smell from TCA were discriminated, and detected at approximately 2 to 4 ppt. Thus, even when the panelists attended to different sensory parameters, the recognition threshold was almost the same between reduction of wine odor and addition of extrinsic odor.

Channel Suppression by Related Substances and Correlation with Human Sensation.

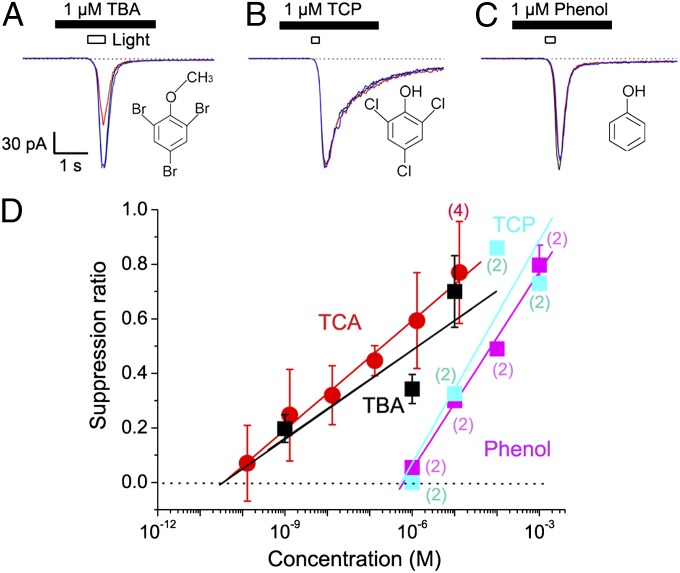

We also tested the suppressive actions of TCA analogues on cAMP responses of ORCs (Fig. 5 A–C). TBA reduced the amplitude of cAMP-induced current with a half SR of 1.4 μM (Fig. 5D), comparable to that of TCA. TCP (a precursor of TCA) and phenol (natural precursor of TCP) suppressed the current with half SRs of 37.6 μM (TCP; Fig. 5D) and 74.9 μM (phenol), which were approximately 200- and 400-fold higher, respectively, than that of TCA (Fig. 5D). Thus, the channel suppression induced by these substances showed a good agreement with the reduction of human olfactory sensation (Table 1). Because much weaker suppressors of CNG channels can mask human olfactory sensations in air phase delivery (8), it is highly likely that TCA also reduces human olfactory perception.

Fig. 5.

Suppression by TBA, TCP, and phenol. (A) Current suppression by 1 µM TBA (A), 1 µM TCP (B), 1 µM phenol (C), and dose-suppression relation (D). Traces: black, control; red, TBA; blue, recovery. Note that the rank order is identical to that of the human perception, TCA equivalent to TBA, which is much greater than TCP. Each plot shows the average value and SD obtained from three tested cells, except for numbers shown in parentheses. Diameter of stimulus pipette was 1 µm.

Suppression by High-LogD Substances.

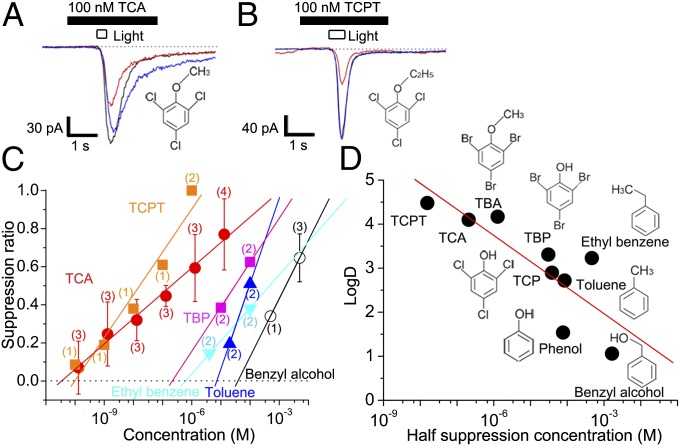

It has been shown that odorant suppression of ion channels becomes stronger as the LogD of the molecule is increased across a range of compounds (26). LogD is a partition coefficient at the octanol/water boundary at fixed pH, a measure of lipophilicity. In the present study, we also studied if such a trend is observed in TCA and phenol derivatives. This information is important for molecular design of novel modifiers of olfaction. As an example, we focused on trichlorophenetole (TCPT), an artificially synthesized TCA derivative with a longer side chain (C2H5 instead of CH3) and higher LogD value (LogD = 4.61) than TCA (LogD = 4.10). Channel suppression by TCPT was slightly stronger than by TCA (half suppression with 15.5 nM in pipette; Fig. 6 A and B). We also examined TBP, toluene, benzyl alcohol, and ethyl benzene. When LogD was plotted against half SR concentration, we observed a positive correlation (Fig. 6 C and D). This result may support the notion that the channel suppression is caused by the partitioning of volatile substances into the lipid bilayer. This would be consistent with the temporal integration seen in the TCA effect (Fig. 3) being caused by slow accumulation of the substance in the ciliary membrane.

Fig. 6.

Current suppression by TCA analogues. (A) Current suppression by 100 nM TCA. Traces: black, control; red, TCA; blue, recovery. (B) Current suppression by 100 nM TCPT, an example of a synthetic compound with a higher LogD than TCA (pH 7.4). (C) Dose-suppression relation for TCA and TCA analogs. Plots: red circles, TCA; orange squares, TCPT; pink squares, TBP; light blue triangles, ethyl benzene; blue triangles, toluene; open circles, benzyl alcohol. The number of cells examined is indicated in parentheses. Each plot shows the average value and SD except for those with n < 3. Plots without error bars show data obtained from one or two cells. (D) Relation between LogD (pH 7.4) and half-suppression concentrations of related compounds. The straight line is a least-square fit to the data. Pipette diameter was 1 µm.

TCA Is Generated in Varieties of Products.

The present study shows that TCA suppresses CNG channel current, which is predicted to reduce olfactory sensation. These observations led us to examine the presence of TCA in foods and beverages that received negative ratings for odor loss but not the presence of a musty odor.

In GC-MS measurements, TCA molecules were detected with high concentrations in a variety of foods and beverages (in ppt; banana peel, 1,500; starch, 100; chicken, 60; peanuts, 20; Japanese sake, 10; cashew nuts, <10; green tea, 5; beer, 1).

Moreover, with GC-olfactometry (GC-O; “GC-sniffing”) and GC-MS, presence of TCA was also recognized in mineral water, tap water, whiskey, apples, chestnuts, eggs, flours, green onions, raisins, sea urchin, shrimp, building materials, food packing films, paper bags, and resin for computers. These products do not include TCA normally (or include TCA at quantities lower than the GC-MS detection threshold). TCA was detected when these products were judged to be of low qualities (i.e., flavor loss and/or unpleasant odor) by their industrial specialists. It thus seems likely that TCA degrades the olfactory quality not only of wines, but also of a wide variety of foods and beverages that have not yet been well investigated.

Discussion

In this study, we showed that TCA and TBA suppress the activity of CNG channels in olfactory cilia. It has been shown that the density of CNG channels in cilia is 100 to 1,000/µm2 (27, 28). The diameter of cilia is 100 to 200 nm, and the length is 10 to 100 μm. As each ORC has approximately 10 cilia, the total transduction current is carried by an enormous number of CNG channels (e.g., approximately 100,000). Our data showed that a remarkably small number of TCA molecules can significantly suppress transduction currents. For the 1-aM effective concentration we observed, 1 μL (1 mm3) of solution contains 0.6 TCA molecules. In our U-tube experiments, ∼1 mL of solution was perfused onto the cell, so the total number of molecules delivered was ∼600. Only a small fraction of these 600 molecules will have a chance to impact the recorded cell and bind or partition into the ciliary membrane.

If suppression is caused by direct binding of TCA molecules to ion channels, only a small fraction of the ion channels would be suppressed, which would not be detectable as a significant reduction of total current. Thus, it seems likely that one TCA molecule suppresses many channels. The TCA effect exhibited temporal integration over a period of tens of seconds and was correlated with LogD when compared across structurally related compounds. This suggests that TCA may partition into the lipid bilayer and achieve an elevated concentration in the lipid microenvironment, or it may affect multiple channels simultaneously by disrupting membrane order. The suppression of individual channels may be visible in macroscopic currents because a high density of CNG channels in olfactory cilia increases the signal-to-noise ratio for the observation of channel perturbations (27–31).

TCA has been well documented as one of the strongest known off-flavor substances, and has been detected in the drinking water (7), beer (5), Japanese sake (6), coffee (3, 9), and various foods (1, 2, 4). It was pointed out in these reports that TCA causes an unpleasant musty odor. Therefore, previous attention was given to TCA only when musty odors were present. Unfortunately, we currently do not have a clear understanding of how extremely low concentrations of TCA can evoke a musty odor. The simplest hypothesis is that TCA molecules bind certain olfactory receptors and activate transduction currents in ORCs at very low concentrations. However, the smallest effective concentration of odorants known to induce responses in individual ORCs is approximately 1 μM (20, 28, 29). On the contrary, the levels of TCA that would evoke musty odors (<5 pM concentration, or 10−4 fold lower) are extremely low for receptor-mediated biological mechanisms, even taking into consideration the expected 102- to 103-fold amplification of afferent signals achieved by convergence of ORC synaptic inputs at olfactory glomeruli (32). We did not observe any detectable ORC excitatory responses in the experiments in which very low concentrations of TCA were applied to ORCs. However, we cannot assume that we surveyed all possible olfactory receptors in the newt. We also note that the repertoire of functional olfactory receptor genes is different between amphibians and mammals, so we cannot rule out the expression of receptors with very high TCA sensitivity in humans.

The rank order of suppression of CNG currents by TCA and its analogues perfectly matched the human recognition of off-flavors, TCA equivalent to TBA, which is much greater than TCP. It is also noteworthy that, in the sensory evaluation, the perceived attenuation of wine odor and the identification of extrinsic TCA odor exhibited almost the same thresholds. Based on these observations, we propose that the reduction of CNG channel activity may induce some kind of pseudoolfactory sensation by inducing an off-response (33), or the suppression of ORC output may itself induce an olfactory sensation. One possibility is a change in central odor coding through inhibitory circuits, e.g., lateral inhibition in the olfactory bulb. In this regard, we may need to revisit past reports of an association between olfactory sensations and odorant effects on membrane fluidity (34). Another possible explanation for the altered quality of perceived odors in the presence of TCA could be a selective differential block of transduction in ORCs expressing some subset of olfactory receptors, thereby distorting the odor code relayed to the brain from the periphery. This might occur if there were a nonuniform transport of TCA to different dorsoventral zones of receptor expression in the olfactory epithelium (35). For instance, TCA or food/beverage odorants released in the oral cavity might have different access to different receptors via a retronasal pathway (36).

The suppression of CNG channels has been reported for compounds that are used in perfumery for the purpose of olfactory masking (8). It is surprising to see that off-flavors in foods/beverages actually exhibit the same effect. In the present study, it was confirmed that potent suppression was caused by similar compounds having a side chain that increases LogD. Our findings not only reveal a likely mechanism of odor loss, but also reveal potential molecular architectures for the development of novel odor-masking agents and potent ion channel inhibitors.

Methods

Cell Dissociation.

Single ORCs were dissociated enzymatically from the olfactory epithelium of the newt (Cynops pyrrhogaster) as described previously (37, 38). The experiments were performed under the latest ethical guidelines for animal experimentation at Osaka University, based on international experimental animal regulations. Animals were chilled on ice and double-pithed. After decapitation, olfactory epithelia were removed. The mucosae were incubated (37 °C, 5 min) in 0.1% (wt/wt) collagenase solution (Ca2+- and Mg2+-free) containing (in mM) 110 NaCl, 3.7 KCl, 10 Hepes, 15 glucose, 1 pyruvate, and 0.001% phenol red, with pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH, and cells were mechanically isolated. Cells were adhered onto the surface of concanavalin A-coated glass coverslip that replaced the bottom of the Petri dish, bathed in normal Ringer solution containing (in mM) 110 NaCl, 3.7 KCl, 3 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 Hepes, 15 glucose, 1 pyruvate (pH adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH before use), and examined with an inverted microscope with Nomarski optics during recording. Cells were maintained at 4 °C until use. Experiments were performed at room temperature (23–25 °C).

Electrophysiology.

Unless otherwise indicated, cells that did not show odorant responses were selected for experiments. Membrane currents were recorded with the whole-cell recording configuration (39). Patch pipettes were fabricated from borosilicate tubing with filament (outer diameter, 1.2 mm; World Precision Instruments) by using a two-stage vertical patch electrode puller (PP-830; Narishige Scientific Instruments). The recording pipette was normally filled with a 119 mM CsCl solution (37). In all pipette solutions, pH was adjusted with CsOH to 7.4 with 10 mM Hepes buffer. For cAMP experiments, 1 mM CaCl2, 5 mM EGTA, and 1 mM of caged cAMP were added (Figs. 1–6 and Figs. S1 and S3). For caged Ca2+ experiments, 5 mM CaCl2 and 10 mM dimethoxy-nitrophenamine (DM-nitrophen) were added without EGTA (Fig. S2).Whole-cell pipette resistance was 10 to 15 MΩ. In all experiments, normal Ringer solution (as described earlier) was used as superfusate. The recording pipette was connected to a patch-clamp amplifier (Axopatch 200B; MDS Analytical Technologies). Signals were low-pass filtered at 0.5 kHz and digitized by an A/D converter (sampling frequency, 1 kHz) connected to a PC operating MS-DOS (PC9821, 80486CPU; NEC) or Windows (xw8600 workstation; HP) with pClamp 8 (MDS Analytical Technologies). Simultaneously, signals were monitored on an oscilloscope and recorded on a chart recorder. UV light and odorant stimulation and data acquisition were regulated by the same computer by using custom software. The results were analyzed by a workstation computer and plotted in Microcal Origin 7.5 software (OriginLab). For curve plots, data were smoothed by 50 Hz averaging, or data sampled at 1/16 kHz were used.

Photolysis of Caged Compound.

The ORC was loaded with caged cAMP (adenosine 3-5-cyclic monophosphate, P1-(2-nitrophenyl) ethyl ester of cAMP; EMD) or with caged Ca2+ (DM-nitrophen; EMD). Caged cAMP was initially dissolved in DMSO at 100 mM, and caged Ca2+ was dissolved in 10 mM CsOH at 100 mM and stored frozen at −20 °C in complete darkness. The stock solution was diluted into the pipette solution to a final concentration of 1 mM (caged cAMP) or 10 mM (caged Ca2+) before each experiment. For photolysis, UV light from a 100-W xenon arc was directed onto the cilia of solitary cells by an epifluorescence attachment. Light stimuli were applied at >20 s intervals to avoid response adaptation. The timing and duration of light illumination were controlled by a magnetic shutter (Copal), and the light intensity was adjusted by a wedge filter under computer control. The light source was mechanically isolated from the microscope to exclude transmission of vibrations (38). Throughout the experiments, we paid particular attention to avoid current saturation. For measurements of suppression by odorants or TCA derivatives, we adjusted light intensity to evoke cAMP responses of 80% to 90% saturating level to ensure we measured the SR at the same level of internal cAMP.

Chemicals and Stimulation.

Chemicals (TCA, TBA, TCP, TBP, 1,8-cineole, ethyl benzene, toluene, benzyl alcohol), were purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry, phenol from Wako Pure Chemical, geraniol from Katayama Chemical, and l-cis-diltiazem from Enzo Life Sciences. TCPT was synthetized in the laboratory of Daiwa Can Company. All LogD values were obtained from the ChemSpider database of the Royal Society of Chemistry on July 10, 2013. For stimuli, chemicals were dissolved in Ringer solution, and this solution was applied to cells by pressure ejection (40) from a glass puffer pipette with a tip diameter ∼1 μm, unless otherwise indicated. As shown in the present study, the solution in the puffer pipette was diluted by one or two orders of magnitude when ejected into the superfusion bath. Stimulus solutions were also applied by using a U-tube system (26).

GC-MS.

For GC and MS measurements, we used a 7890A GC system (Agilent Technologies) and a Jms-Q1000GC MKII system (JEOL), respectively. The column was a model DB-5MS (30 m × 0.32 mm × 0.5 μm film thickness; Agilent Technologies). The GC conditions were as follows: column temperature, 60 °C (for 5 min) to 250 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min; injector temperature, 250 °C; ion source temperature, 23 °C; ionization voltage, 70 eV (electron ionization); and selected ion monitoring measurement ion m/z, deuterium labeled TCA (TCAd5) 197, 199, 215; and TCA, 195, 197, and 210. A spiked surrogate reagent was used as an internal standard for quantification. The value of TCA for TCAd5 was 0.87 (coefficient of variation = 3.6%; n = 5). Under these conditions, the off-flavor causing substance was at 0.001 ppb, and a linear relationship was obtained in the range of 0.001 to 10 ppb.

GC-O.

GC-O was performed by using a 6890GC device (Agilent Technologies) with a DB-5 column (30 m × 0.53 mm × 1.0 μm film thickness; Agilent Technologies). The GC conditions were as follows: column temperature, 100 °C (for 5 min) to 250 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min; injector temperature, 250 °C; injector mode, splitless; and injection amount, 2 μL. The gas obtained by branching immediately before entering the flame ionization detector (4:1) was subjected to GC-O. The GC-O experiments were performed by four panelists (n = 2 male and n = 2 female; age, 24–56 y) trained in-house to detect musty odors in foods and beverages.

Evaluation of Wine Odor.

Detection thresholds of off-flavor substances were examined by panelists who were selected from employees of Daiwa Can Company. The evaluation complied with the guidelines for ethics regarding human epidemiological studies at Osaka University, Daiwa Can Company, and Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan. Human sensory tests were approved by the Ethics committee of Daiwa Can Company. The triangle test approved by JIS or BSI/ISO was used for the determination of threshold. Protocols are described in SI Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. King-Wai Yau and Graeme Lowe for their detailed comments, Dr. Saho Ayabe for her advice on the sensory evaluation, Mr. Takeomi Sato for his expert advice on cork taint and flavor loss, Mr. Hisao Watanabe for his advice on chemicals and discussions, and Mr. Katsuyoshi Syudo for collecting sensory evaluation data. This work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Grants 22700414 (to H.T.) and 22500357 (to T.K.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. S.D.R. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1300764110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Buser HR, Zanier C, Tanner H. Identification of 2,4,6-trichloroanisole as a potent compound causing cork taint in wine. J Agric Food Chem. 1982;30:359–362. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henricks DM, Lamond DR. 2,3,4,6-tetrachloroanisole association with musty taint in chickens and microbiological formation. Nature. 1972;235(5335):222–223. doi: 10.1038/235222a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spadone JC, Takeoka G, Liardon R. Analytical investigation of Rio off-flavor in green coffee. J Agric Food Chem. 1990;38:226–233. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Engel CP, de Groot AP, Weurman C. Tetrachloroanisol: A source of musty taste in eggs and broilers. Science. 1966;154(3746):270–271. doi: 10.1126/science.154.3746.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGarrity MJ, McRoberts C, Fitzpatrick M. Identification, cause, and prevention of musty off-flavors in beer. MBAA TQ. 2003;40:44–47. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miki A, Isogai A, Utsunomiya H, Iwata H. Identification of 2,4,6-trichloroanisole (TCA) causing a musty/muddy off-flavor in sake and its production in rice koji and moromi mash. J Biosci Bioeng. 2005;100(2):178–183. doi: 10.1263/jbb.100.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qi F, et al. Ozonation catalyzed by the raw bauxite for the degradation of 2,4,6-trichloroanisole in drinking water. J Hazard Mater. 2009;168(1):246–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.02.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takeuchi H, Ishida H, Hikichi S, Kurahashi T. Mechanism of olfactory masking in the sensory cilia. J Gen Physiol. 2009;133(6):583–601. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200810085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kato H, Sato K, Takui T. Analysis of iodine-like (chlorine) flavor-causing components in Brazilian coffee with Rio flavor. Food Sci Technol Res. 2011;17:347–352. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buck L, Axel R. A novel multigene family may encode odorant receptors: A molecular basis for odor recognition. Cell. 1991;65(1):175–187. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90418-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kurahashi T, Menini A. Mechanism of odorant adaptation in the olfactory receptor cell. Nature. 1997;385(6618):725–729. doi: 10.1038/385725a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takeuchi H, Kurahashi T. Identification of second messenger mediating signal transduction in the olfactory receptor cell. J Gen Physiol. 2003;122(5):557–567. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takeuchi H, Kurahashi T. Mechanism of signal amplification in the olfactory sensory cilia. J Neurosci. 2005;25(48):11084–11091. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1931-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takeuchi H, Kurahashi T. Distribution, amplification, and summation of cyclic nucleotide sensitivities within single olfactory sensory cilia. J Neurosci. 2008;28(3):766–775. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3531-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen TY, Takeuchi H, Kurahashi T. Odorant inhibition of the olfactory cyclic nucleotide-gated channel with a native molecular assembly. J Gen Physiol. 2006;128(3):365–371. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ache BW. Odorant-specific modes of signaling in mammalian olfaction. Chem Senses. 2010;35(7):533–539. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjq045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kleene SJ, Gesteland RC. Calcium-activated chloride conductance in frog olfactory cilia. J Neurosci. 1991;11(11):3624–3629. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-11-03624.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurahashi T, Yau KW. Co-existence of cationic and chloride components in odorant-induced current of vertebrate olfactory receptor cells. Nature. 1993;363(6424):71–74. doi: 10.1038/363071a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lowe G, Gold GH. Nonlinear amplification by calcium-dependent chloride channels in olfactory receptor cells. Nature. 1993;366(6452):283–286. doi: 10.1038/366283a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lowe G, Gold GH. Olfactory transduction is intrinsically noisy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92(17):7864–7868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reisert J, Bauer PJ, Yau KW, Frings S. The Ca-activated Cl channel and its control in rat olfactory receptor neurons. J Gen Physiol. 2003;122(3):349–363. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stephan AB, et al. ANO2 is the cilial calcium-activated chloride channel that may mediate olfactory amplification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(28):11776–11781. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903304106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sagheddu C, et al. Calcium concentration jumps reveal dynamic ion selectivity of calcium-activated chloride currents in mouse olfactory sensory neurons and TMEM16b-transfected HEK 293T cells. J Physiol. 2010;588(pt 21):4189–4204. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.194407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cook NJ, Hanke W, Kaupp UB. Identification, purification, and functional reconstitution of the cyclic GMP-dependent channel from rod photoreceptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84(2):585–589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.2.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Breunig E, Kludt E, Czesnik D, Schild D. The styryl dye FM1-43 suppresses odorant responses in a subset of olfactory neurons by blocking cyclic nucleotide-gated (CNG) channels. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(32):28041–28048. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.233890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kishino Y, Kato H, Kurahashi T, Takeuchi H. Chemical structures of odorants that suppress ion channels in the olfactory receptor cell. J Physiol Sci. 2011;61(3):231–245. doi: 10.1007/s12576-011-0142-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kurahashi T, Kaneko A. High density cAMP-gated channels at the ciliary membrane in the olfactory receptor cell. Neuroreport. 1991;2(1):5–8. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199101000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhandawat V, Reisert J, Yau KW. Elementary response of olfactory receptor neurons to odorants. Science. 2005;308(5730):1931–1934. doi: 10.1126/science.1109886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Menini A, Picco C, Firestein S. Quantal-like current fluctuations induced by odorants in olfactory receptor cells. Nature. 1995;373(6513):435–437. doi: 10.1038/373435a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Larsson HP, Kleene SJ, Lecar H. Noise analysis of ion channels in non-space-clamped cables: Estimates of channel parameters in olfactory cilia. Biophys J. 1997;72(3):1193–1203. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78767-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kurahashi T, Kaneko A. Gating properties of the cAMP-gated channel in toad olfactory receptor cells. J Physiol. 1993;466:287–302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Drongelen W, Holley A, Døving KB. Convergence in the olfactory system: Quantitative aspects of odour sensitivity. J Theor Biol. 1978;71(1):39–48. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(78)90212-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kurahashi T, Lowe G, Gold GH. Suppression of odorant responses by odorants in olfactory receptor cells. Science. 1994;265(5168):118–120. doi: 10.1126/science.8016645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kashiwayanagi M, Kurihara K. Evidence for non-receptor odor discrimination using neuroblastoma cells as a model for olfactory cells. Brain Res. 1985;359(1-2):97–103. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)91416-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miyamichi K, Serizawa S, Kimura HM, Sakano H. Continuous and overlapping expression domains of odorant receptor genes in the olfactory epithelium determine the dorsal/ventral positioning of glomeruli in the olfactory bulb. J Neurosci. 2005;25(14):3586–3592. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0324-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Furudono Y, Cruz G, Lowe G. Glomerular responses to retronasal airflow revealed by optical imaging in the mouse olfactory bulb. BMC Neurosci. 2013;14:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-14-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kurahashi T. Activation by odorants of cation-selective conductance in the olfactory receptor cell isolated from the newt. J Physiol. 1989;419:177–192. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takeuchi H, Kurahashi T. Photolysis of caged cyclic AMP in the ciliary cytoplasm of the newt olfactory receptor cell. J Physiol. 2002;541(pt 3):825–833. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.016600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hamill OP, Marty A, Neher E, Sakmann B, Sigworth FJ. Improved patch-clamp techniques for high-resolution current recording from cells and cell-free membrane patches. Pflugers Arch. 1981;391(2):85–100. doi: 10.1007/BF00656997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ito Y, Kurahashi T, Kaneko A. [Pressure control instrumentation for drug stimulation] Nippon Seirigaku Zasshi. 1995;57(3):127–133. Japanese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.