Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

Glottal relationships during swallowing dominate the etiology of dysphagia. We investigated the pharyngo-glottal relationships during basal and adaptive swallowing.

METHODS:

Temporal changes in glottal closure kinetics (frequency, response latency, and duration) with spontaneous and adaptive pharyngeal swallows were defined in 12 infants using concurrent pharyngoesophageal manometry and ultrasonography of the glottis.

RESULTS:

Frequency, response latency, and duration of glottal closure with spontaneous swallows (n = 53) were 100%, 0.27±0.1 s, and 1±0.22 s, respectively. The glottis adducted earlier (P < 0.0001 vs. upper esophageal sphincter relaxation) within the same respiratory phase as swallow (P = 0.03). With pharyngeal provocations (n = 41), glottal adduction (pharyngo-glottal closure reflex (PGCR)) was noted first and then again with pharyngeal reflexive swallow (PRS). The frequency, response latency, and duration of glottal closure with PGCR were 100%, 0.56±0.13 s, and 0.52±0.1 s, respectively. Response latency to PRS was 3.24±0.33 s; the glottis adducted 97% within 0.36±0.08 s in the same respiratory phase (P = 0.03), and remained adducted for 3.08±0.71 s. Glottal adduction was the quickest with spontaneous swallow (P = 0.04 vs. PGCR), and the duration was the longest during PRS (P < 0.005 vs. PGCR or spontaneous swallow).

CONCLUSIONS:

Glottal adduction during basal or adaptive swallowing reflexes occurs in either respiratory phase, thus ensuring airway protection against pre-deglutitive or deglutitive aspiration. The independent existence and magnitude (duration of adduction) of PGCR suggests a hypervigilant state of the glottis in preventing aspiration during swallowing or during high gastroesophageal reflux events. Investigation of pharyngeal–glottal relationships with the use of noninvasive methods may be more acceptable across the age spectrum.

INTRODUCTION

Airway safety and problems in swallowing constitute a significant challenge in neonates and infants who have undergone intensive care (1). Inadequate airway protection during swallowing is an important contributory factor to feeding-related morbidity. Appropriate laryngeal closure reflex mechanisms can ensure safe swallowing and may protect against aspiration, as recognized in studies on adults (2). Anterograde aspiration has been known to occur in the pre-deglutitive phase, deglutitive phase, and in post-deglutitive phase, and retrograde aspiration may result from gastroesophageal reflux (GER) events (3). The integrity of aerodigestive protective reflexes in infants is not well understood; however, it is of relevance in infants with acute life-threatening events or aspiration syndromes (4). The protective function of the glottis in relation to the pharyngeal phase of swallowing in infants is not clear in health or in dysphagia.

Swallowing-related laryngeal adduction has been determined in adult human and animal models using radiological or videoendoscopic methods (2,5-7). Such methods are not practical in infants, and prolonged evaluations are not feasible to quantify temporal characteristics of pharyngeal–glottal interactions. Therefore, in earlier studies, we have validated the function of adduction of vocal folds and arytenoids during concurrent nasolaryngoscopy and noninvasive ultrasonography of glottis (USG) (8,9). In subsequent studies, we have defined the esophago-glottal closure reflex using concurrent manometry and USG (10,11). We have also defined the phar yngeal-upper esophageal sphincter (UES) relationships separately during spontaneous and induced swallows (12,13). However, pharyngo-glottal relationships have not been defined in infants.

In infants, the pharynx and larynx have several functions; however, a primary continuous function is to provide airway protection to ensure safe swallowing (14). This study was undertaken in healthy infants to accomplish the following aims: (i) to develop a safe noninvasive method to evaluate continuous glottal motion during concurrent pharyngoesophageal manometry; (ii) to define the frequency and magnitude of the pharyngo-glottal relationships during spontaneous swallows and on pharyngeal provocation; and (iii) to evaluate the temporal relationships between the coordination of glottal closure with pharyngo-UES interactions and respiratory phases. With these aims, we tested the hypothesis that glottal responses are different between those induced on spontaneous swallows and those induced on pharyngeal provocation using concurrent pharyngoesophageal manometry and USG.

METHODS

Participants

We evaluated 12 neonates (8 male:4 female; 27.4±1.1 weeks gestational age (GA) (median: 26.3 weeks, range: 23.0–35.0 weeks) at 44.1±1.8 weeks postmenstrual age (PMA) (median: 42.1 weeks, range: 37.1–56.1). GA was determined by evaluating maternal history and obstetric data and PMA was calculated by adding chronological ages to GA. At the time of study, the average body weight was 3.5±0.3 kg (median: 3.5 kg, range: 2.3–5.5 kg). Healthy orally fed subjects were included, and those with structural, chromosomal, or neurological anomalies were excluded from the study. The Human Research Review Committee at the Nationwide Children’s Research Institute/Nation wide Children’s Hospital’s IRB (Institutional Review Board) approved the study protocol. Informed consent and HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) of 1996 authorization were obtained from the parents of the study participants. IRB and HIPAA compliance were observed. To ensure subject protection, all studies were carried out at the crib side in the nursery, and subject safety was monitored by close clinical observation.

Pharyngo-esophageal manometry

The subjects underwent pharyngoesophageal manometry as described by us (12,13). A specially designed pharyngoesophageal manometry catheter (Dentsleeve/Mui Scientific, Mississauga, ON, Canada) was passed nasally without using sedation or anesthesia. The catheter had a 4.0-cm UES sleeve (Dentsleeve) to identify UES characteristics and three side ports below the UES (E1, E2, E3, spaced 2.5, 4.5, 6.5 cm, respectively, below the center of the UES sleeve) to recognize peristalsis. In addition, a pharyngeal recording port (located 3.0 cm above the center of the UES sleeve) was used to record pharyngeal swallow waveform signal, and a pharyngeal infusion port (located 5.0 mm proximal to the pharyngeal recording port) was used to stimulate the pharynx. Both the posteriorly oriented pharyngeal ports and the flattened UES sleeve conformed to the flat anteroposterior slit-like UES configuration. Therefore, once in position, the sleeve prevented the axial rotation of the UES catheter. As a result, pharyngeal perfusion port and stimulation ports were always maintained in posterior orientation. The catheter assembly was connected to the pneumohydraulic micromanometric water perfusion system (Solar Gastro, Medical Measurement Systems, Dover, NH) through the resistors (Mui Scientific) and pressure transducers, (TNF-R (tumor necrosis factor receptor), Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). All studies were carried out in the supine position, with the transducers placed at the level of the subject’s esophagus (mid-axillary line).

Respiratory inductance plethysmography

Concurrent with manometry, thoracic and abdominal respiratory movements were recorded using respiratory inductance plethysmography (Respitrace, Viasys, Conshohocken, PA). The upstroke of the respiratory waveform correlated with inspiration evidenced by chest rise, and the downstroke of the waveform correlated with expiration evidenced by the return of the chest to baseline. The respiratory recordings were integrated with all other measurement modalities (Solar Gastro).

Swallow: electromyography

Concurrently, submental EMG (electromyography; Solar Gastro), used to document swallow signal, was recorded by placing surface EMG leads in the submental region as described previously (12,13). The submental EMG was integrated with all other measurement modalities within the system (Solar Gastro), and was used to correlate swallow EMG with pharyngeal waveform signal.

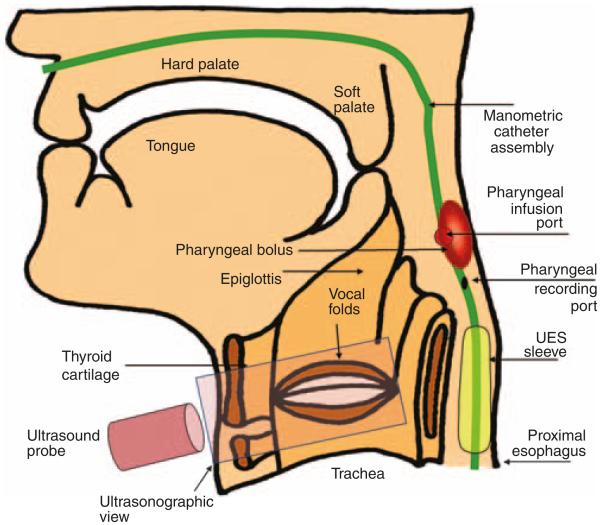

Concurrent USG

USG was performed once per subject to monitor the continuous glottal motion concurrent with pharyngo–UES–esophageal motility and respiratory phases, as described by us (8–11). In this study, USG was performed using a Siemens Acuson Sequoia 512 ultrasound system (Siemens, Mountain View, CA) equipped with a 15–8 MHz linear array transducer (operating between 12 and 14 MHz). The ultrasound transducer was placed on the anterior neck, using gel as an acoustic coupling medium (Figure 1). The video output signals (30 Hz) derived from USG were integrated and synchronized in real time with manometry signals using the Meteor 2 video card (Medical Measurements System, Dover, NH) (8–11). This technique allowed us to analyze USG images frame by frame along with concurrent manometry recordings (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Methods to elicit pharyngo-glottal interactions. A manometry catheter is placed with ports in the pharynx, upper esophageal sphincter (UES), and proximal esophagus. An ultrasound transducer was placed on the anterior aspect of the neck. The stimulus was infused through the pharyngeal infusion port–located posterior, and the pharyngo-glottal interactions were evaluated.

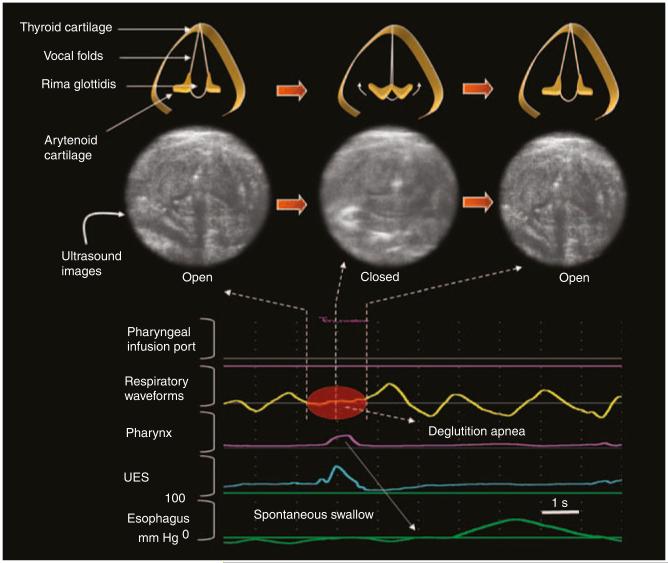

Figure 2.

Glottal closure reflex during spontaneous swallow. The spontaneous swallow is evident by pharyngeal waveform and upper esophageal sphincter (UES) relaxation. Deglutition apnea is evident as a brief pause in respiration. The inset represents the magnified images of glottal ultrasound frames during a spontaneous swallow showing a real-time sequence of glottal abduction to complete adduction to abduction. The occurrence of complete glottal adduction is visible in the middle ultrasound frame.

Experimental protocol

These studies were carried out in healthy infants who were receiving oral feedings and were not on any respiratory stimulants, neuroactive agents, prokinetics, or acid-suppressive medications. Subject safety was monitored by both the principal investigator and the nurse throughout the study.

The catheter assembly was passed transnasally and positioned through the pharynx, UES, and esophagus. The baseline high-pressure zone of the UES and its relaxation characteristics during primary peristalsis were identified to ensure a proper placement of the catheter assembly (12,13). A swallow occurrence was documented by the submental surface EMG of the mylohyoid/geniohyoid muscle group and as well by (i) the pharyngeal waveform, (ii) characteristic UES deglutitive relaxation, and (iii) propagation through esophageal body waveforms. Infants were first allowed to adapt (approximately 10–15 min) to the catheter systems and subsequently, USG was performed concurrent to the manometry. Subjects were studied in only one concurrent session that lasted about 15–20 min. During this period, the USG transducer was readjusted to ensure the subject comfort and adaptation.

The study had two fundamental objectives, i.e., evaluation of the glottal function during (i) spontaneous swallows and (ii) pharyngeal provocation. To investigate the former, continuous USG was recorded during spontaneous swallow-induced primary peristalsis. To investigate the latter, we applied the previously tested infantpharyngeal provocation protocol (12). Briefly, during a period of pharyngoesophageal quiescence, first, 0.5 and 1.0 ml volumes of air were infused through the pharyngeal infusion port to induce pharyngeal reflexive swallows (PRSs). Next, sterile water (0.1, 0.3, and 0.5 ml volumes) was administered. Infusions were administered randomly with respect to the respiratory phase, as the investigator (S.R.J.) had no control of the infant’s respiratory pattern. To prevent the confounding effects, attention was given to the following: (i) infusions that were administered during pharyngeal–esophageal manometric quiescence; (ii) the presence of esophageal clearance that was documented by anterograde waveforms; and (iii) infusions that were administered during a period of quiet breathing. This approach was used to ensure the absence of residual effects of stimulus and to prevent the effect of propagating waveforms on the more proximal locus. Administration of the stimulus was documented through the manometric signal (Figure 1).

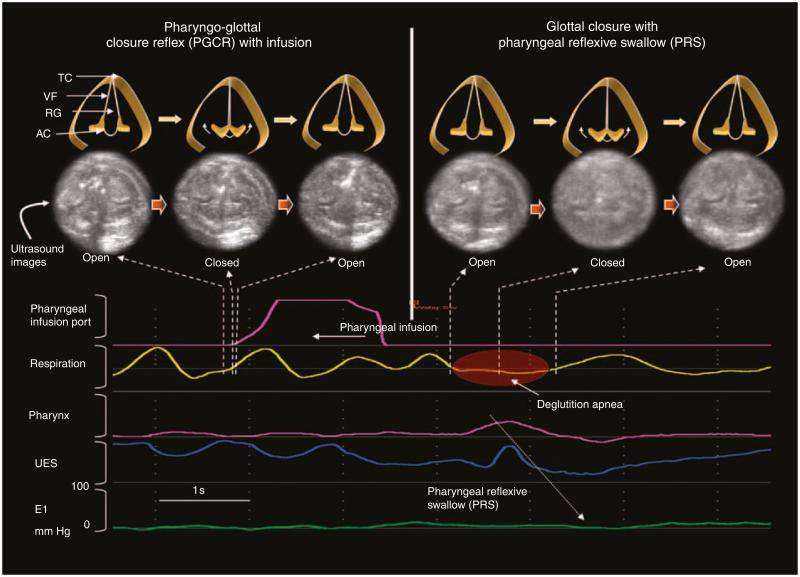

Data analysis

Spontaneous swallow and PRS were recognized as previously defined by us (12,13). Respiratory phase changes during spontaneous and induced swallows were recognized by the presence of phase alterations or by a pause in relation to the pharyngeal waveform signal. The respiratory pause during the occurrence of swallow was characterized as deglutition apnea (15,16). Simultaneously, changes in glottal fold motion during spontaneous respiration and swallows were recognized. During pharyngeal provocation, glottal adduction (the pharyngo-glottal closure reflex (PGCR)) was noted first, followed by a return to normal glottal motion. Glottal closure occurred again during PRS (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of pharyngeal infusion on glottal motion. The pharyngeal infusion is evident as a waveform peak in the pharyngeal infusion port signal and pharyngeal infusion swallow (PRS) is evident by pharyngeal waveform and associated upper esophageal sphincter (UES) relaxation. Two glottal motion changes were identified in (a) the phase of pharyngeal provocation and (b) the phase of PRS. AC, arytenoid cartilage; RG, rima glottidis; TC, thyroid cartilage; VF, vocal folds.

Subsequent to the study, a frame-by-frame analysis was carried out to measure the temporal characteristics of glottal motion during spontaneous swallow, pharyngeal infusion, and PRS. Data were analyzed by four observers (S.R.J., A.G., M.W., and B.C.) as follows: first, the presence or absence of glottal adduction, deglutition apnea, and PRS were documented; second, the duration in seconds for the (i) response latency of glottal adduction and (ii) the duration of complete glottal adduction (from the onset of complete glottal adduction to the return of glottal abduction); and third, the response latency in seconds was measured for the PRS. Finally, the respiratory phase and the deglutition apnea during the events were evaluated. The effects of infusion media and volumes were also compared.

Statistical analysis

On the basis of a priori definitions (8–11,13,17,18), glottal closure events were recognized in relation to swallowing and respiration by three observers (S.R.J., B.C., and A.G.). Concordance and reproducibility of the data analysis were further computed on the basis of the agreement rates between two independent observers (A.G. and M.W.) for the association of deglutition apnea during spontaneous swallow, PRS, and PGCR. Both the observers identified the occurrence of deglutition apnea (Table 1) with 100% accuracy during spontaneous swallow and PRS, and with 98.6% accuracy during PGCR.

Table 1.

Incidence of glottal closure and deglutition apnea during spontaneous swallows and pharyngeal stimulation

| SSGCR (n = 53 swallows) |

PGCR (n = 41 infusions) |

PRS (n = 31 events) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Glottal closure | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| DA | 98% (52/53) | 20% (8/41) | 71% (22/31) |

| Swallow | 100% | NA | 100% |

DA, deglutition apnea; PGCR, pharyngo-glottal closure reflex; PRS, pharyngeal reflexive swallow; SSGCR, spontaneous swallow–related glottal closure.

The data for this study comprised several measurements per subject. Repeated measurement models (PROC MIXED) with subject as a cluster variable and compound symmetry variance-covariance matrix were used to analyze all the continuous outcome variables (response time to glottal closure with spontaneous swallow, response time to PRS, response time to PGCR, and duration of glottal adduction during PGCR). These models take into account the correlations within the subjects. The same model was used to analyze the relationship between each of the continuous variables and stimulus type and volume. The χ2 test or Fisher's exact test was carried out to analyze binary outcome variables during the respiratory phases (inspiration or expiration) and during glottal closure with each of the predictors listed above. Pairwise comparisons among the three different types of response times and among the three different types of glottal closure times were made. Data were adjusted for multiple testing by applying the Bonferroni method. SAS (SAS v.9.1. Institute, Cary, NC) was used to perform the analyses. Mean±s.e.m. or least squared means±s.e.m. is reported, unless stated otherwise. P values and adjusted P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

With a sample size of 12 subjects from whom measures due to different stimuli are collected, a study would have 80% power to detect the differences found in this study between the response latency and duration of glottal closure caused by spontaneous swallows or PRSs.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics

Subjects (N = 12) were of appropriate growth for gestation at birth (weight: 1.1±0.2 kg, length: 35.4±1.9 cm, head circumference: 24.2±1.2 cm, mean±s.d.). The median APGAR scores were 6 and 8 at 1 and 5 min, respectively. At evaluation, the cohort was normally distributed with respect to the postmenstrual age (44.1±1.8 week, median: 42.1 week, range: 37.1–56.1 week) and had age-appropriate growth parameters (weight: 3.5±0.3 kg, length: 48.3±1.6 cm, and head circumference: 35.7±1.1 cm). At evaluation, the subjects were healthy, physiologically stable, and transitioning to oral feeds; at the time of discharge, all the subjects were receiving oral feeds.

Observations during concurrent manometry and USG

The subjects were studied only in one concurrent session that lasted for approximately 15–20 min during which no side effects or concerns were noted. The glottal motion was observed during normal inspiration and expiration. Complete glottal adduction was never observed during this normal inspiration and expiration or during pharyngoesophageal quiescence. Complete glottal adduction was observed only during the following events: (i) during spontaneous primary peristalsis (Figure 2) and (ii) during pharyngeal provocation with PGCR (Figure 3) and also with PRS (Figure 3).

Glottal kinetics with spontaneous swallows

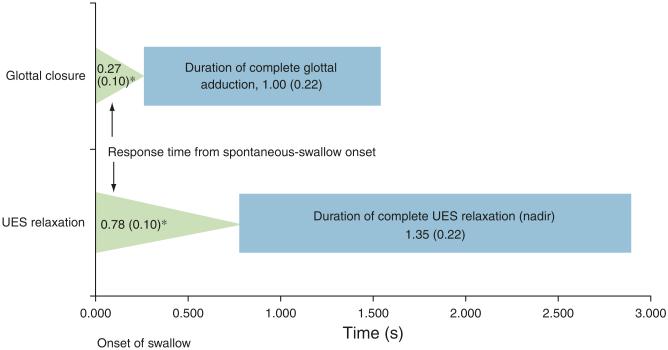

Glottal kinetics was evaluated concurrent with respiratory phase changes during 53 spontaneous swallows (average ~4 per subject), and the frequency of glottal adduction and deglutition apnea occurrences is described. (Table 1 and Figure 2). The response latency for complete glottal closure from the onset of pharyngeal waveform was 2.9-fold quicker (vs. UES relaxation onset, P < 0.0001, Figure 4) and the durations were similar (P = NS).

Figure 4.

Comparison of glottal closure and upper esophageal sphincter (UES) relaxation during spontaneous swallow. Response latency to glottal closure was compared with response time to UES relaxation (triangles, * P < 0.0001) and duration of complete glottal adduction was compared with UES nadir (P = NS).

Out of 53 swallows, 32 occurred during the inspiratory phase and 21 in the expiratory phase. To test the relationship of the respiratory phase of glottal closure with the respiratory phase of pharyngeal swallow, four possible scenarios were visualized (Figure 5) and are described in Table 2. Glottal adduction is likely to occur in the same respiratory phase as the onset of pharyngeal waveform (odds ratio = 3.58, confidence interval: 1.13, 11.35, P = 0.03).

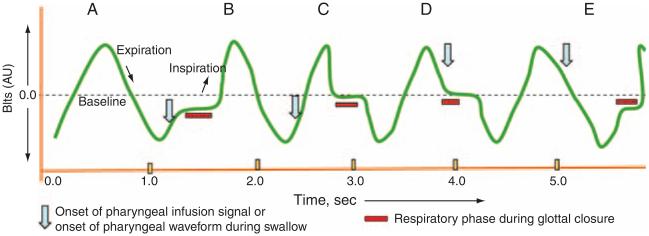

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of the onset of pharyngeal provocation or the onset of swallow (arrows) in relation to the glottal closure (bars) with reference to their concomitant respiratory phases (waveform). Four possible respiratory phase relationships were recognized (B, C, D, and E). Scenario A represents basal inspiration and expiration. In B, both the onset of pharyngeal event and glottal adduction occurred in inspiration. In C, the onset of pharyngeal event occurred in inspiration, and glottal adduction occurred in expiration. In D, both the onset of pharyngeal event and glottal adduction occurred in expiration. In E, the onset of pharyngeal event was during expiration and glottal adduction occurred in inspiration of the next respiratory phase.

Table 2.

Glottal closure during spontaneous swallow: relationship with respiration

| Respiratory phase during spontaneous-swallow waveform onset |

||

|---|---|---|

| Inspiration (n =32) | Expiration (n =21) | |

| Respiratory phase during glottal-closure onset | ||

| Inspiration | 22 (69%) (B) | 8 (38%) (E) |

| Expiration | 10 (31%) (C) | 13 (62%) (D) |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

The glottal closure is likely to happen in the same respiratory phase as the onset of the spontaneous swallow (OR = 3.58, CI: 1.13, 11.35, P = 0.03).

B, C, D, and E refer to scenarios B, C, D, and E in Figure 5.

Glottal kinetics with pharyngeal provocation

Overall, glottal responses to 41 pharyngeal infusions (26 water and 15 air infusions) were analyzed, and the frequencies of PGCR and deglutition apnea are described in Table 1. The response latency was 0.56±0.13 s, and the glottis remained adducted for 0.52±0.10 s. Th e glottal response latency and the duration of glottal adduction remained similar even with different media (air vs. water) (P = NS) and with different infusion volumes of the same media (P = NS). Th e glottal adduction was noted in inspiration or expiration regardless of the respiratory phase of the pharyngeal provocation (Table 3).

Table 3.

Pharyngo-glottal closure reflex: relationship with respiration

| Respiratory phase during pharyngeal infusion |

||

|---|---|---|

| Inspiration (n =24) | Expiration (n =14) | |

| Respiratory phase during glottal-closure onset | ||

| Inspiration | 13 (54%) (B) | 5 (36%) (E) |

| Expiration | 11 (46%) (C) | 9 (64%) (D) |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; PGCR, pharyngo-glottal closure reflex.

The PGCR is likely to happen in any respiratory phase regardless of the respiratory phase during pharyngeal infusion (OR = 2.13, CI: 0.55, 8.26, P = 0.27).

B, C, D, and E refer to scenarios B, C, D, and E in Figure 5.

Glottal kinetics during PRSs

During PRSs, glottal adduction reoccurred (Figure 3), and the frequency occurrence was 85% (35 responses/41 infusions). All the water infusions (26/26) resulted in PRSs, whereas only 60% (9/15) air infusions resulted in PRSs (P = 0.001).

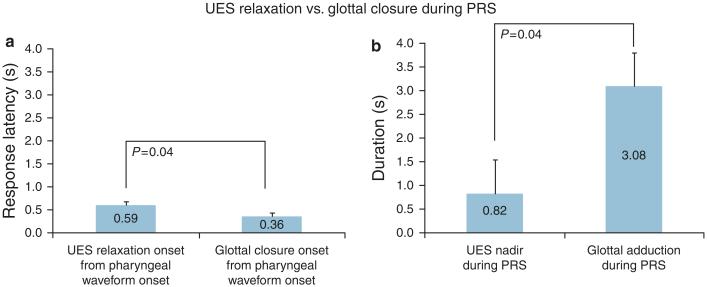

Out of these 35 PRS responses (26 water and 9 air infusions), USG was not interpretable with 4 sequences. Therefore, with the 31 PRS sequences, the response latency to PRS was 3.24±0.33 s from the onset of pharyngeal infusion, and the frequency of glottal adduction was 100%. Complete glottal closure onset was 0.6-fold sooner (vs. UES relaxation onset, P = 0.04), and the duration of glottal adduction was 3.8-fold longer (vs. UES nadir, P = 0.04, Figures 3 and 6) Glottal adduction occurred in the same respiratory phase of the reflexive pharyngeal swallow waveform onset (P < 0.0001, Table 4).

Figure 6.

Comparison of response latency (a) and response duration (b) of upper esophageal sphincter (UES) relaxation with glottal closure are described during pharyngeal infusion swallow (PRS).

Table 4.

Glottal closure with pharyngeal reflexive swallow: relationship with respiration

| Respiratory phase during pharyngeal reflexive swallow |

||

|---|---|---|

| Inspiration (n =11) | Expiration (n =20) | |

| Respiratory phase during glottal-closure onset | ||

| Inspiration | 11 (100%) (B) | 1 (5%) (E) |

| Expiration | 0 (0%) (C) | 19 (95%) (D) |

PGCR, pharyngo-glottal closure reflex.

The PGCR is likely to happen in the same phase of respiration as the pharyngeal reflexive swallow, P < 0.0001. B, C, D, and E refer to scenarios B, C, D, and E in Figure 5.

Comparison of glottal kinetics during spontaneous swallows and on pharyngeal provocation

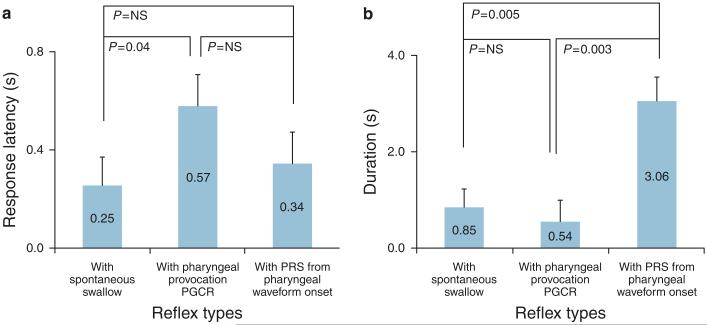

The response latency and response duration of glottal adduction during spontaneous swallows and with pharyngeal provocation that resulted in PRS were different (analysis of variance, P < 0.05, Figure 7a and b). Owing to the variance–covariance matrix calculation effect, the average and s.e.m. values were minimally different from those reported previously, although the data were the same. Compared with PGCR, the response latency for the onset of glottal adduction was 2.3-fold faster with spontaneous swallow (P = 0.04) and was similar (P = NS) to PRS (Figure 7a). On the other hand, compared with PGCR and with spontaneous swallow, the glottis remained closed longer with PRS (P < 0.005, Figure 7b ).

Figure 7.

Comparison of response latency (a) and duration of glottal adduction (b) are described across the three events (spontaneous swallow, pharyngo-glottal closure reflex (PGCR), pharyngeal infusion swallow (PRS)).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have defined the unique pharyngo-glottal relationships for the first time in infants using a novel technique, concurrent manometry, and USG. The following are the salient features: (i) frequency occurrence, magnitude, and temporal relationships between swallowing reflexes and changes in glottal motion can be evaluated safely in infants; (ii) spontaneous or induced swallow-related glottal adduction and PGCR are independent reflexes that can occur in inspiration or expiration; and (iii) the response acuity and response duration of glottal adduction are different under different situations, namely spontaneous swallow, pharyngeal provocation, and PRS. In addition, these approaches may permit a prolonged evaluation of aerodigestive reflexes in patients with dysphagia with the potential of characterizing the pathophysiological basis for symptoms across the age spectrum.

Glottal adduction is a consequence of contraction of the glottal adductors (thyroarytenoid, cricothyroid, lateral cricoarytenoid, and inter arytenoid) innervated by the recurrent laryngeal nerve with a notable exception of cricothyroid (innervated by the external division of superior laryngeal nerve) (14). The pharynx is innervated by superior laryngeal nerve (from Vagus) and may also receive contributions from the glossopharyngeal nerve. In response to pharyngeal stimulation, glottal adduction is seen in healthy infants, similar to that in adult human or animal models. Thus, this sensory–motor relationship between pharyngeal afferents and laryngeal efferents support the function of PGCR, i.e., protection of airway with pharyngeal provocation may happen during swallowing or during more proximal GER events. Therefore, recognition and characteristics of this reflex allows the evaluation of superior laryngeal nerve and recurrent laryngeal nerve integrity.

With pharyngeal provocation, PGCR occurred first followed by swallowing (PRS) concurrent with glottal adduction (Figure 3). This event signifies further enhancement of airway protection during the actual pharyngo-UES phase of swallowing. Furthermore, glottal adduction was always seen in spontaneous swallows that may be volitional or reflexive in nature, a fact that cannot be differentiated in infants. The fact that glottal closure occurred during all such events (Figure 2) supports the need for airway protection during swallowing events in infants, regardless of the mechanism of pharyngeal swallow or of premature birth.

Evaluation of the glottal function using endoscopy methods in dysphagia can be limited to the identification of gross structural pathology and vocal cord movement. The current methods may be more acceptable to study aerodigestive reflexes in health or dysphagia across the age spectrum, as they are less invasive and are therefore less stressful. For example, the occurrence of peristaltic reflexes favoring pharyngoesophageal clearance and preventing the entry of stimulus into the proximal aerodigestive tract can be protective. Such provocations and responses may occur spontaneously during GER events and remain uneventful in healthy infants. On the other hand, high-risk infants such as those born prematurely or those surviving with chronic lung disease (CLD) are at an increased risk of dysphagia, GER disease, and apparent life-threatening events. We hypothesize that some of the symptoms of these conditions can be explained from the failure or exaggeration of protective reflexes, and either of these results may cause physiological derangement contributing to the aerodigestive pathology in infants.

We have previously defined and quantified the sensory– motor relationships between the mechanosensitive and osmosensitive pharyngeal stimuli and pharyngeal reflexes (PRS and PUCR (pharyngo-UES contractile reflex) PUCR) in healthy infants (12). PRS was most frequently observed in neonates, unlike the PUCR that occurs more frequently in adults (17,18). In this study, during glottal adduction with PGCR and PRS, significant differences were noted with respect to their temporal characteristics, frequency occurrence, response latency, and response duration. This may suggest that these reflexes may be activated by different sensory–motor pathways, and that their functions may be complementary in aerodigestive clearance or protection. The fact that the airway closure may be a hypervigilant response is suggested by the occurrence of PGCR 5.7-folds earlier than the PRS, and that PRS occurring later lends support to steer clear the of stimulus. In this study, low volumes (0.1 ml) evoked PGCR followed by PRS and larger volumes (>0.3 ml, ~3 drops) resulted in PGCR and multiple PRS. Some of these findings may explain the frequent swallowing as an auto-resuscitation mechanism noted in high-risk neonates who are also at risk for airway compromise.

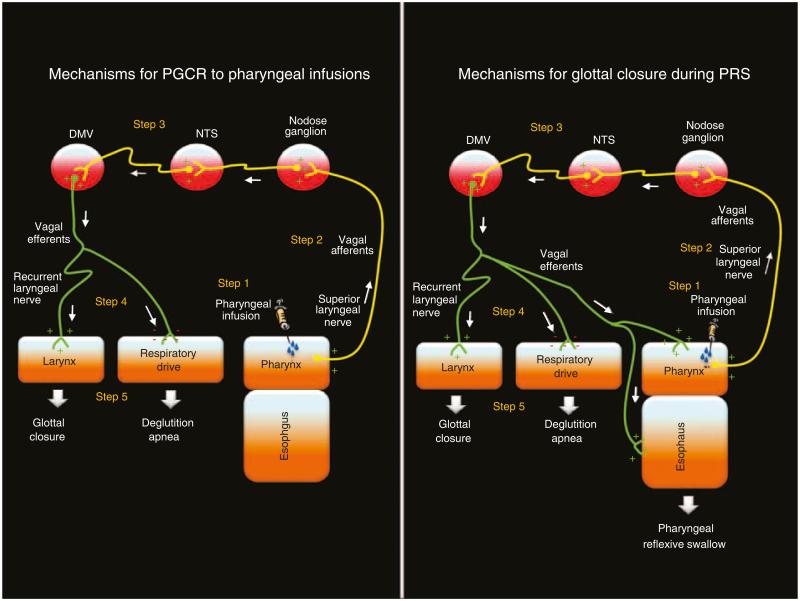

We also tested the relationship of PGCR with inspiratory or expiratory phases. During normal inspiration and expiration, respectively, vocal cords abduct and incompletely adduct, but are not completely adducted. However, complete adduction was observed in either phase of respiration during spontaneous or induced swallows (as in PRS), as well as during PGCR. Furthermore, an abrupt glottal closure in either phases of respiration was noted regardless of the respiratory phase in which pharyngeal waveform onset or pharyngeal provocation occurred. The stimulus may have caused mechanosensitive or osmosensitive stimulation transmitting sensory impulses to the brain stem through the afferent nerves (cranial nerves IX, X). The efferent signals traverse in the vagus through the recurrent laryngeal and superior laryngeal nerves to the laryngeal adductor muscles (6,19–22). Phar yngeal afferents may have activated two motor pathways (Figure 8), namely peristaltic reflexes and glottal closure reflex. The fact that PGCR occurred in either respiratory phase suggests that closure of the glottal opening took precedence over the completion of respiratory phase and that the respiratory drive mediated by the respiratory center and or by the Hering–Breuer reflex may be interrupted (23). This has been observed as deglutition apnea in this study (16,24).

Figure 8.

Schematic representation of the neural control mechanism responsible for glottal and pharyngeal events during pharyngeal infusions (pharyngo-glottal closure reflex (PGCR)) and during pharyngeal infusion swallow (PRS) (adapted from Shaker et al. (6); Yoshida et al. (19); Broussard and Altschuler (20); Goyal et al. (21); Lang et al.; (22)): In step 1, pharyngeal infusion stimulates pharyngeal receptors. In step 2, the sensory signals from pharyngeal receptors are carried to the central nervous system through vagus (X) and glossopharyngeal (IX) nerves. In step 3, the sensory inputs are modulated at various vagal nuclei level. In step 4, the motor response is carried by the efferent vagal nerves to the laryngeal muscles and respiratory apparatus (as in PGCR) and also to the foregut musculature (as in spontaneous or reflex swallowing).

The administration of the stimulus was by random selection with regard to the respiratory phase. This is in contrast to the adult studies, wherein voluntary control and slower breathing rates may have modified the glottal responses. Deglutition, glottal closure reflex, and deglutition apnea occur predominantly in the expiratory phase in adults (16,24). The findings in this study in infants are different in that, regardless of the respiratory phase of stimulation or the onset of pharyngeal waveform, glottal adduction can occur in either respiratory phase. This supports the presence of a break in neural outputs controlling inspiration or expiration. For such an intricate arrangement in neural networks to function, the vagal nucleus is likely to coordinate the regulation between swallowing, glottal motion, and respiratory drive. Such a system is functional in healthy infants, and can be measured reproducibly. Further studies are needed to clarify the mechanisms in infants with aerodigestive symptoms.

As PGCR always occurred with pharyngeal provocation earlier than PRS, it is likely that this mechanism may ensure airway protection from pre-deglutitive aspiration, as in premature bolus spill during buccopharyngeal swallowing or high GER events. Furthermore, a reoccurrence of glottal adduction during PRS may ensure airway protection from deglutitive aspiration. These responses may be a manifestation of hyper-alert airway defenses as evidenced by significantly quicker response latency to glottal adduction compared with UES relaxation onset. This inference is further supported by the fact that glottal adduction significantly correlated with deglutition apnea. Collectively, these findings suggest close integration of pharyngeal, glottal, UES, and respiratory rhythm, and such integration is possibly orchestrated in the vagal nuclear complex (Figure 8).

The following potential clinical implications were identified for the evaluation of pharyngo-glottal relationships: (i) The pharynx participates in the regulation of safe breathing and safe swallowing. However, an inadequacy of such functions can be of concern among infants with aerodigestive problems, such as those with dysphagia, CLD or GER disease, or those born prematurely. Definition of the integrity of supra-esophageal reflexes may explain the aberrant neuromotor mechanisms responsible for aerodigestive maladaptation, anterograde or retrograde aspiration, or for the prevalence of apparent life-threatening events. (ii) The true incidence of glottal problems is unclear in neonates and infants undergoing intensive care, and can at best be underestimated. Similar problems in adults are increasingly prevalent (25). These problems assume importance particularly among those who have undergone chronic presence of tubes in the airway or digestive tract, instrumentation, ventilation, cardiac surgery, or ligation of patent ductus arteriosus (which is in close relation to the recurrent laryngeal nerve). Any or all of these procedures may affect the sensory-motor integrity of aerodigestive reflexes, and further work is needed to evaluate the adaptive mechanisms that may prevent aerodigestive compromise. For example, left vocal-fold paralysis is a significant concern post cardiac surgery (26,27), as the vagal nerve plexus or the left recurrent laryngeal nerve may be the undesirable target of injury. The consequences of aerodigestive compromise and impaired clearance may potentially cause symptoms related to glottal edema, post-extubation stridor, floppy airway, laryngotracheomalacia, bronchospasm, or GER. (iii) In the evaluation of aspiration, an absence or delay in the occurrence of PGCR may predispose to pre-deglutitive aspiration or microaspiration. The mechanisms of chronic cough can also be systematically studied using these novel methods. Furthermore, an absence or delay in glottal closure during spontaneous swallow or during PRS may provide evidences for deglutitive aspiration. A delay in the initiation of swallow or failed peristaltic propagation on pharyngeal stimulation may potentially contribute to the high risk of aerodigestive problems.

In conclusion, we defined the existence of pharyngo-glottal and PRS interactions in infants using novel methods, concurrent manometry, and USG. Pharyngeal provocation resulted in two independent responses: glottal closure (PGCR) and PRS. During the latter event, glottal closure also occurred. Glottis adduction happened in either phase of respiration, suggesting an inhibition of the respiratory drive in both phases, providing credence to airway protective function of this reflex entity resulting from the presence of a stimulus within the pharynx. The methods and approaches described in this paper can be applicable to study the pharyngo-glottal pathophysiology across all ages owing to its noninvasive nature.

Study Highlights.

WHAT IS CURRENT KNOWLEDGE

Pharyngo-glottal closure reflex (PGCR) has been defined in human adults and animal models using endoscopic methods; such methods activate a wider sensory area in evoking the laryngeal adductor response.

Pharyngo-glottal closure reflex (PGCR) has been defined in human adults and animal models using endoscopic methods; such methods activate a wider sensory area in evoking the laryngeal adductor response. Endoscopic methods are not practicable for the study of physiology or pathophysiology in neonates, infants, or children.

Endoscopic methods are not practicable for the study of physiology or pathophysiology in neonates, infants, or children. Although PGCRs may have a causal role in protecting the airway against aspiration, the sensory-motor aspects of this reflex remain unclear across the age spectrum.

Although PGCRs may have a causal role in protecting the airway against aspiration, the sensory-motor aspects of this reflex remain unclear across the age spectrum.

WHAT IS NEW HERE

PGCR has been defined in healthy neonates with novel noninvasive methods, using concurrent esophageal manometry and ultrasonography of the glottis.

PGCR has been defined in healthy neonates with novel noninvasive methods, using concurrent esophageal manometry and ultrasonography of the glottis. PGCR occurs on pharyngeal stimulation earlier than the occurrence of peristaltic reflexes, thus suggesting alert airway defenses in health.

PGCR occurs on pharyngeal stimulation earlier than the occurrence of peristaltic reflexes, thus suggesting alert airway defenses in health. The methods applied in this study permit evaluation of the glottal motion during swallowing or pharyngeal stimulation, and can be useful approaches in all ages either in healthy or in diseased patients.

The methods applied in this study permit evaluation of the glottal motion during swallowing or pharyngeal stimulation, and can be useful approaches in all ages either in healthy or in diseased patients.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants RO1 DK 068158 (Jadcherla) and P01DK068051 (Jadcherla/Shaker).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Guarantor of the article: Sudarshan R. Jadcherla, MD, FRCPI, DCH.

Potential competing interests: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mercado-Deane MG, Burton EM, Harlow SA, et al. Swallowing dysfunction in infants less than 1 year of age. Pediatr Radiol. 2001;31:423–8. doi: 10.1007/s002470100456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaker R, Ren J, Bardan E, et al. Pharyngo glottal closure reflex: characterization in healthy young, elderly and dysphagic patients with predeglutitive aspiration. Gerontology. 2003;49:12–20. doi: 10.1159/000066504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shaker R, Hogan WJ. Reflex-mediated enhancement of airway protective mechanisms. Am J M ed. 2000;108(Suppl 4a):8S–14S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00289-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allen J, Zwerdling R, Ehrenkranz R, et al. American Thoracic Society. Statement on the care of the child with chronic lung disease of infancy and childhood. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:356–96. doi: 10.1164/rccm.168.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Logemann JA, Rademaker AW, Pauloski BR, et al. Normal swallowing physiology as viewed by videofluoroscopy and videoendoscopy. Folia Phoniatr Logop. 1998;50:311–9. doi: 10.1159/000021473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaker R, Medda BK, Ren J, et al. Pharyngoglottal closure reflex: identification and characterization in a feline model. Am J Physiol Gastrointestinal Liver Physiol. 1998;275:521–5. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.275.3.G521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dua K, Bardan E, Ren J, et al. Effect of chronic and acute cigarette smoking on the pharyngoglottal closure reflex. Gut. 2002;51:771–5. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.6.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jadcherla SR, Gupta A, Stoner E, et al. Novel non-invasive technique for evaluation of glottis motion in infants and children: comparison of Ultrasonography (USG) and transnasal endoscopic approach. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:S-2–A-300. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jadcherla SR, Gupta A, Stoner E, et al. Correlation of glottal closure using concurrent ultrasonography and nasolaryngoscopy in children: a novel approach to evaluate glottal status. Dysphagia. 2006;21:75–81. doi: 10.1007/s00455-005-9002-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jadcherla SR, Gupta A, Stoner E, et al. Characterization of esophago-glottal closure reflex (EGCR) in healthy neonates using a novel non-invasive ultrasonography of glottis (USG) technique concurrent with esophageal stimulation. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:S-2–A-410. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jadcherla SR, Gupta A, Coley BD, et al. Esophago-glottal closure reflex in human infants: a novel reflex elicited with concurrent manometry and ultrasonography. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2286–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01401.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jadcherla SR, Duong HQ, Hofmann C, et al. Characteristics of upper oesophageal sphincter and oesophageal body during maturation in healthy human neonates compared with adults. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2005;17:663–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2005.00706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jadcherla SR, Gupta A, Stoner E, et al. Pharyngeal swallowing: defining pharyngeal and upper esophageal sphincter relationships in human neonates. J Pediatr. 2007;151:597–603. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Susan S. Gray's Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice. 39 Churchill Livingstone; United Kingdom: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jadcherla SR, Duong HQ, Walther T, et al. Coordination of deglutition and phases of respiration in preterm and term babies. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:3208A. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shaker R, Li Q, Ren J, et al. Coordination of deglutition and phases of respiration: effect of aging, tachypnea, bolus volume, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Physiol. 1992;263(5):G750–5. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1992.263.5.G750. part 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ren J, Xie P, Lang IM, et al. Deterioration of the pharyngo-UES contractile reflex in the elderly. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1563–6. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200009000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shaker R, Ren J, Xie P, et al. Characterization of the pharyngo-UES contractile reflex in humans. Am J Physiol. 1997;273(4):G854–8. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.273.4.G854. part 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshida Y, Tanaka Y, Hirano M, et al. Sensory innervation of the pharynx and larynx. Am J M ed. 2000;108(4A):51S–61S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00342-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Broussard DL, Altschuler SM. Central integration of swallow and airway protective reflexes. Am J Med. 2000;108(4A):62S–7S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00340-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goyal RK, Padmanabhan R, Sang Q. Neural circuits in swallowing and abdominal vagal afferent-mediated lower esophageal sphincter relaxation. Am J Med. 2001;111(8A):95S–105S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)00863-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lang IM, Dean C, Medda BK, et al. Differential activation of medullary nuclei during different phases of swallowing in the cat. Brain Res. 2004;1014:145–63. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tryfon S, Kontakiotis T, Mavrofridis E, et al. Hering-Breuer reflex in normal adults and in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and interstitial fibrosis. Respiration. 2001;68:140–4. doi: 10.1159/000050483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nishino T, Yonezawa T, Honda Y. Effects of swallowing on the pattern of continuous respiration in human adults. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1985;132:1219–22. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1985.132.6.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McClave SA, DeMeo MT, DeLegge MH, et al. North American summit on aspiration in the critically ill patient: consensus statement. J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2002;26:S80–5. doi: 10.1177/014860710202600613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zbar RI, Chen AH, Behrendt DM, et al. Incidence of vocal fold paralysis in infants undergoing ligation of patent ductus arteriosus. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;61:814–6. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(95)01152-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clement WA, El-Hakim H, Phillipos EZ, et al. Unilateral vocal cord paralysis following patent ductus arteriosus ligation in extremely low-birth-weight infants. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;134:28–33. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2007.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]