The patient

A 48-year-old fisherman from Amazonas (north of Brazil) developed a small papule on the anterior left leg after a traumatic injury with a piece of wood 20 years ago. Over the course of years, multiple large, confluent, reddish to brownish nodules with eventual ulceration came into being on the left leg and extended to the left thigh. There was a solitary, domed-shaped nodule on the right arm (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Multiple confluent papules and nodules in the left leg. [Copyright: ©2013 Jeunon et al.]

Histopathology

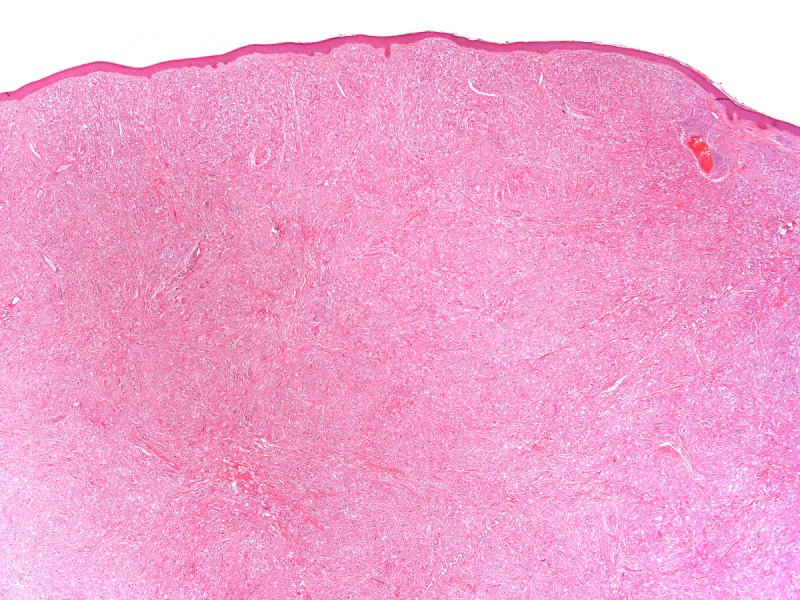

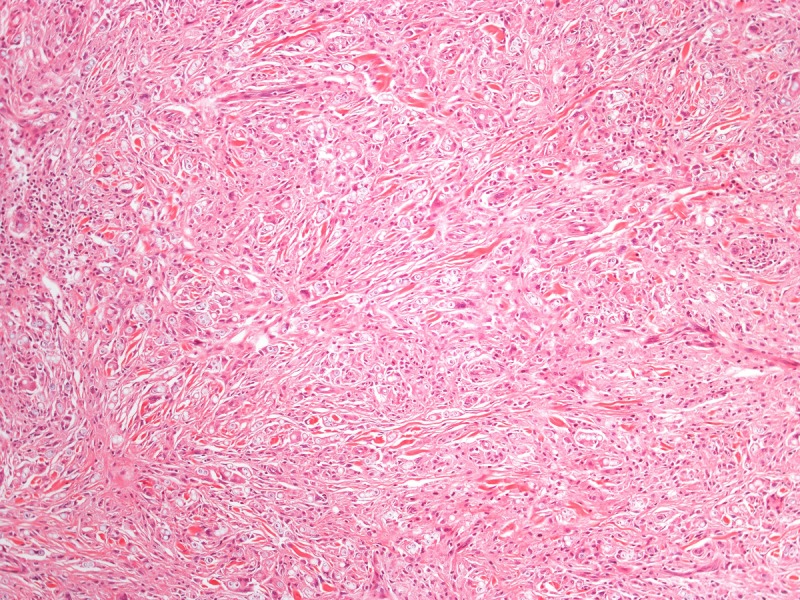

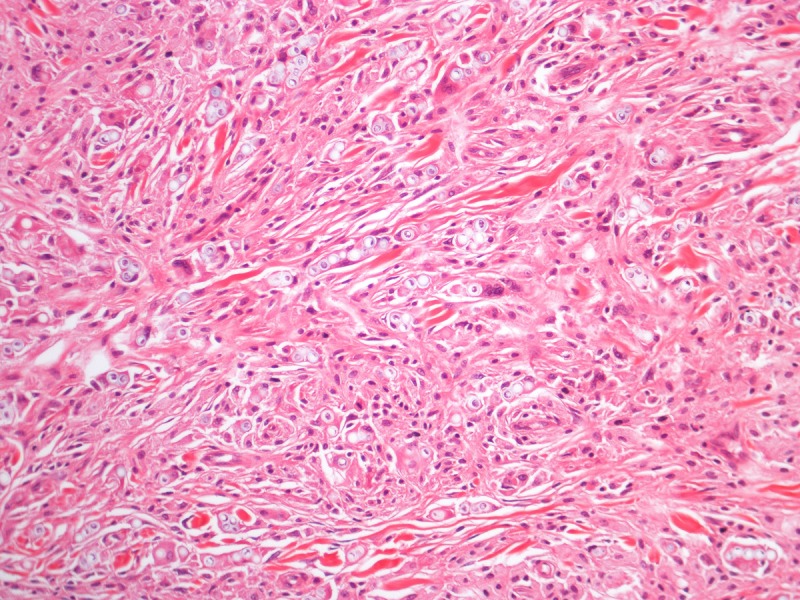

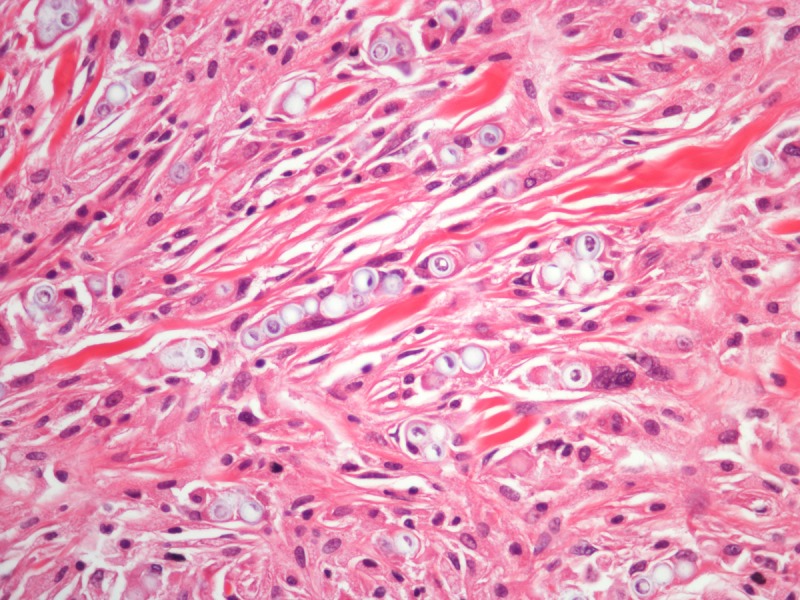

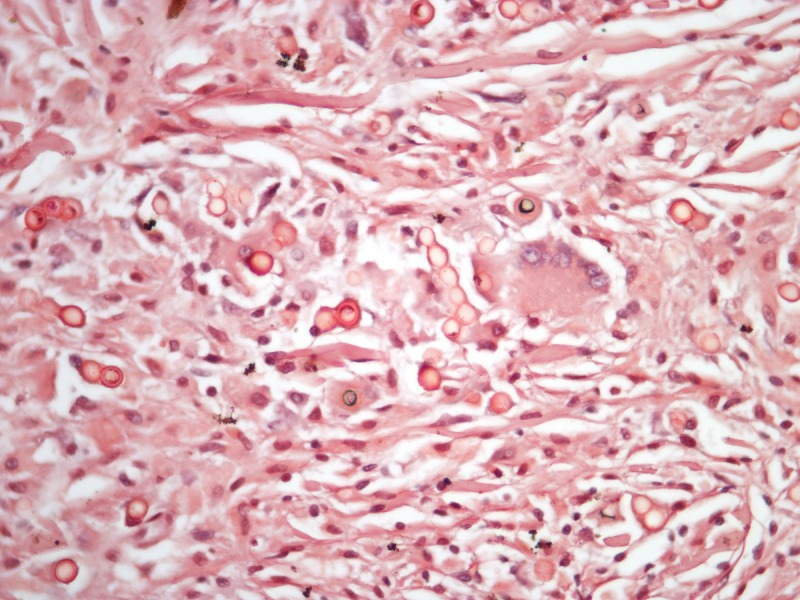

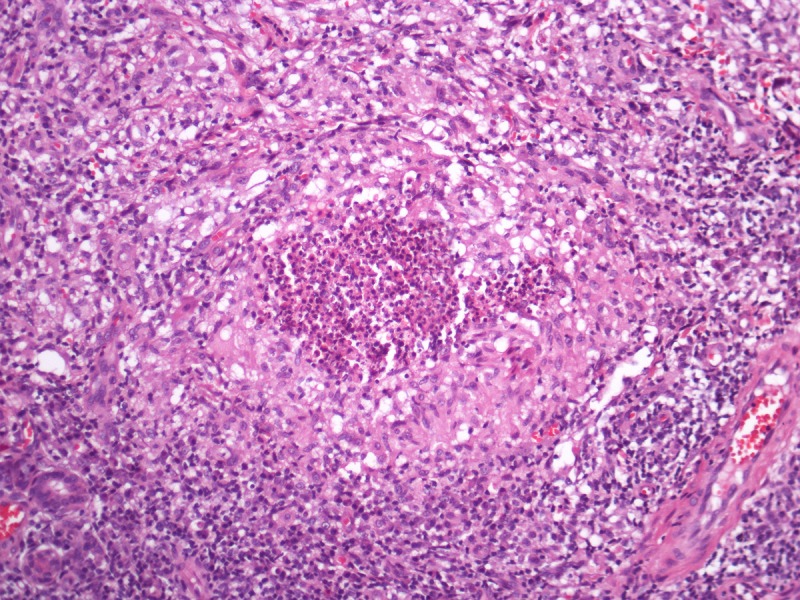

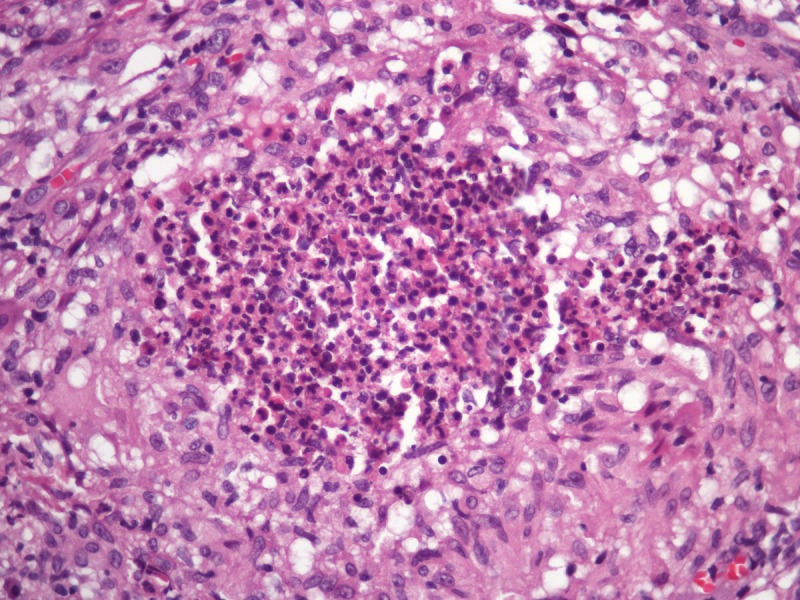

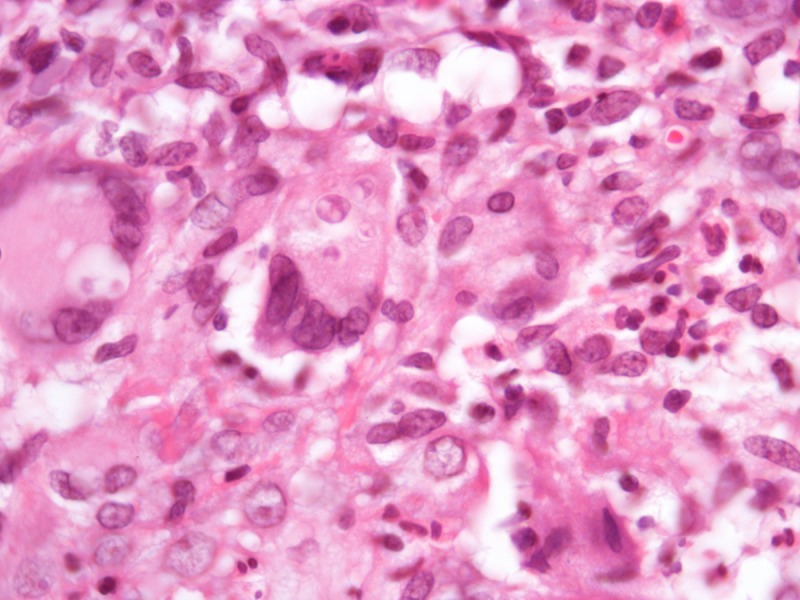

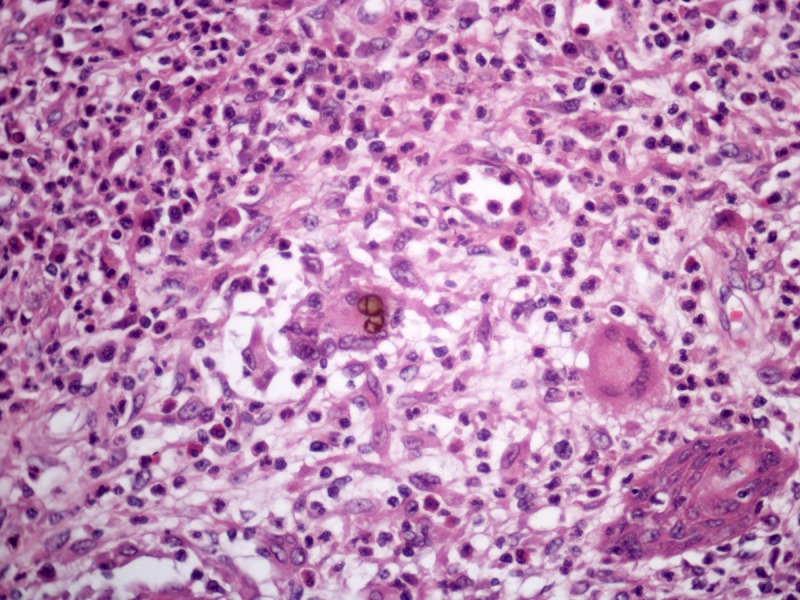

What is your diagnosis (Figures 2 and 3)?

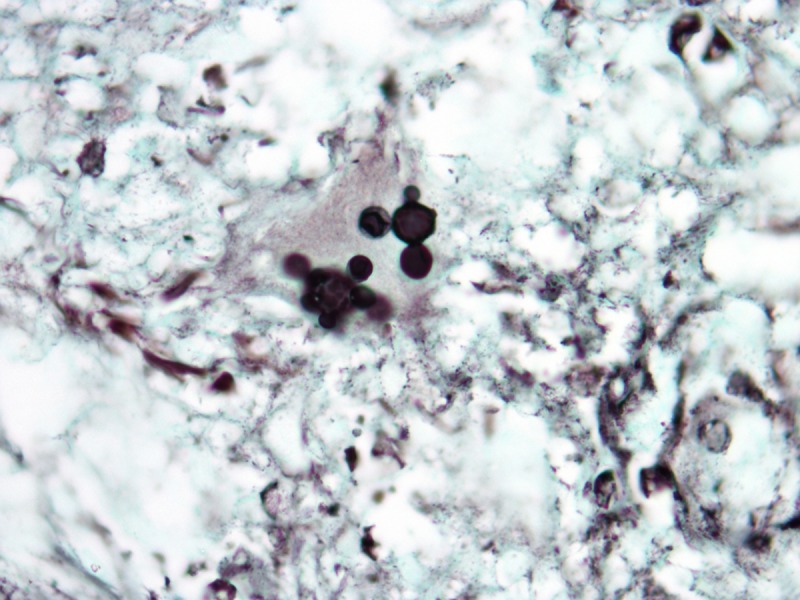

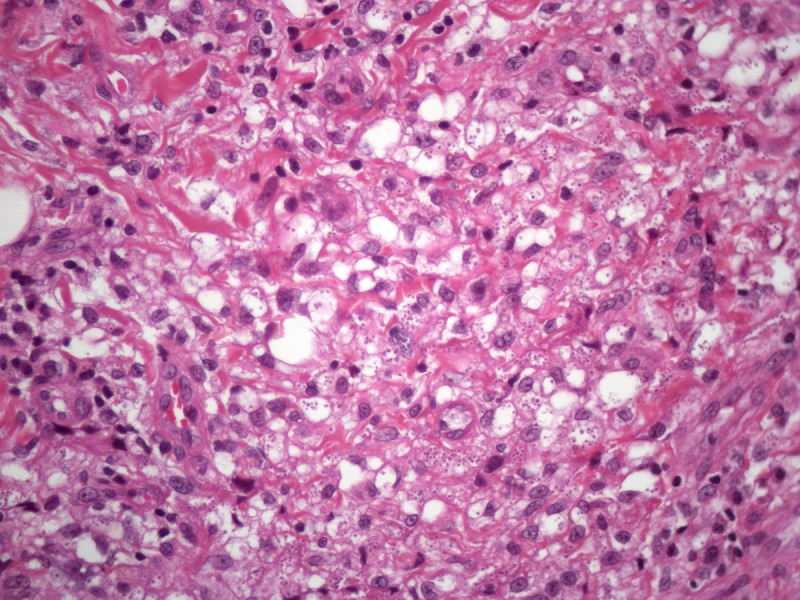

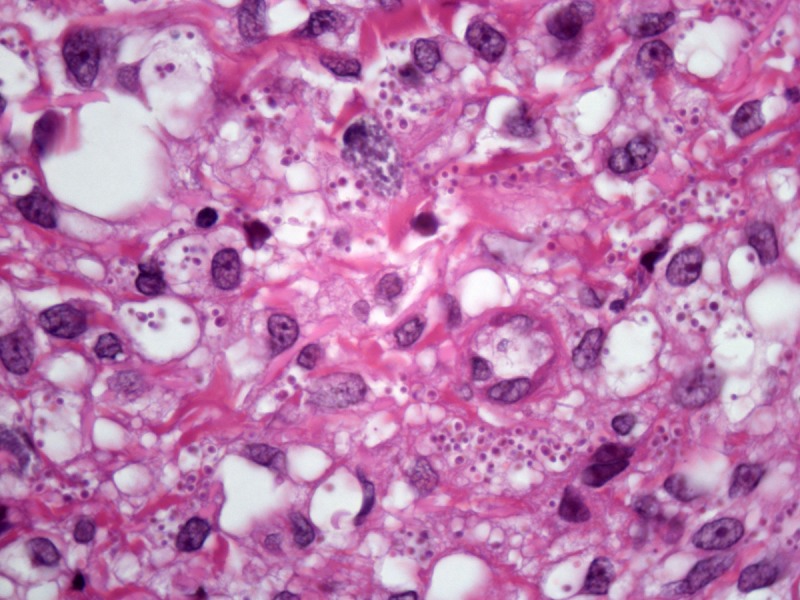

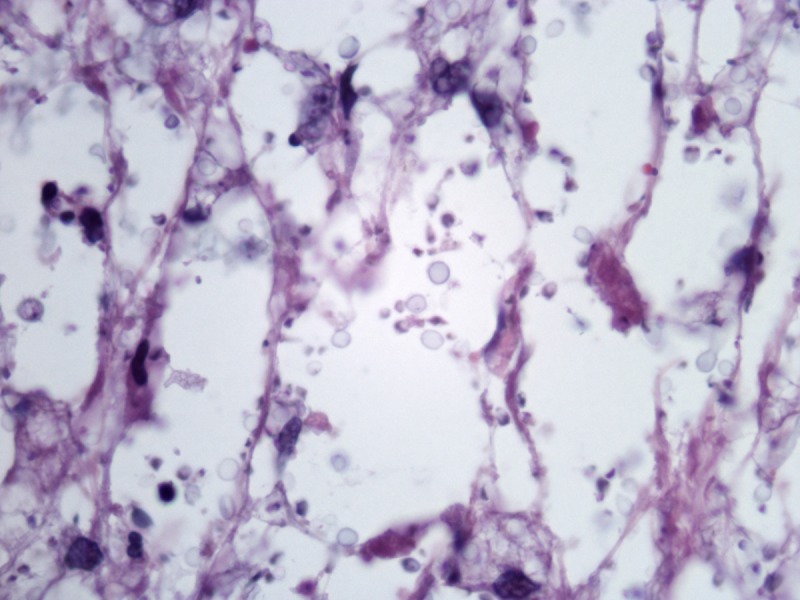

Figure 2.

Histopathology of a lesion from the left leg. H&E, 20, 100, 200 and 400×. [Copyright: ©2013 Jeunon et al.]

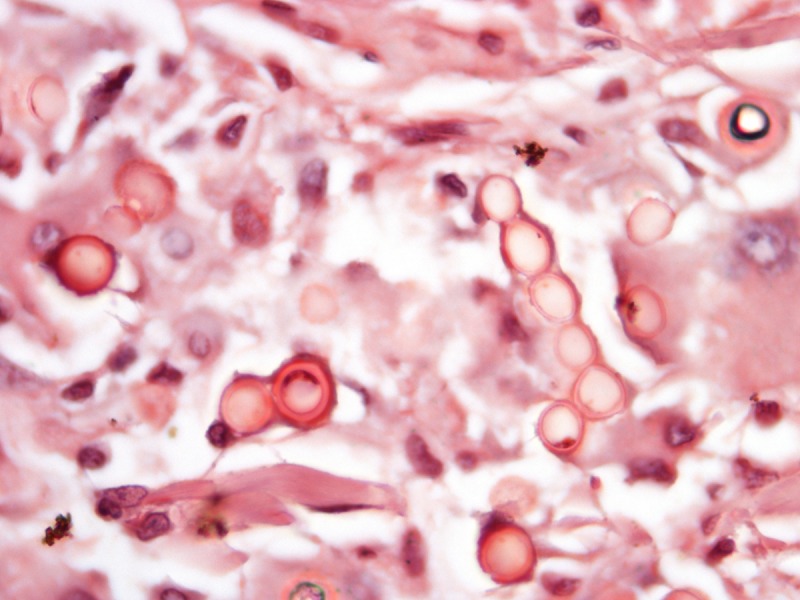

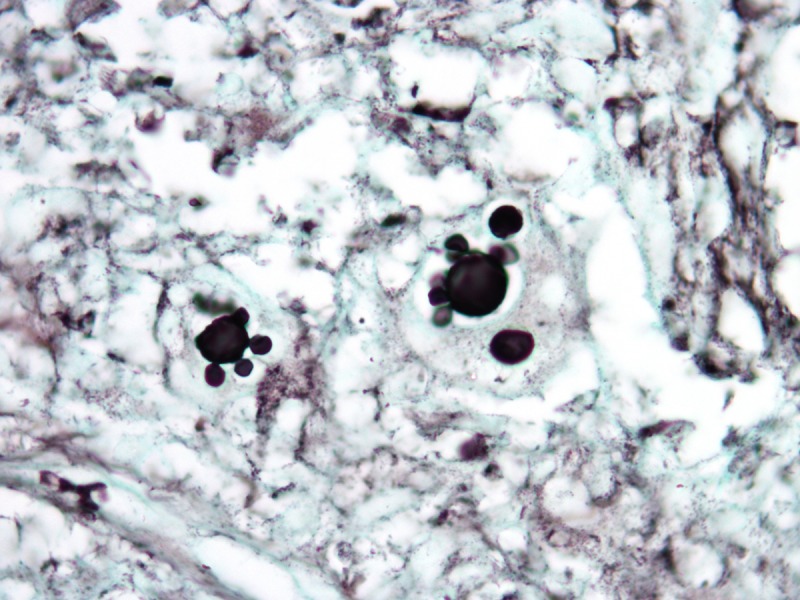

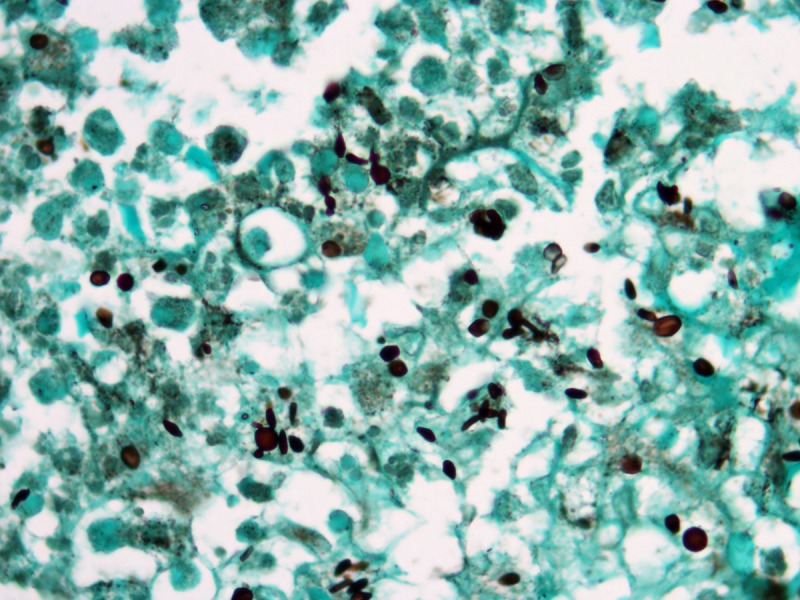

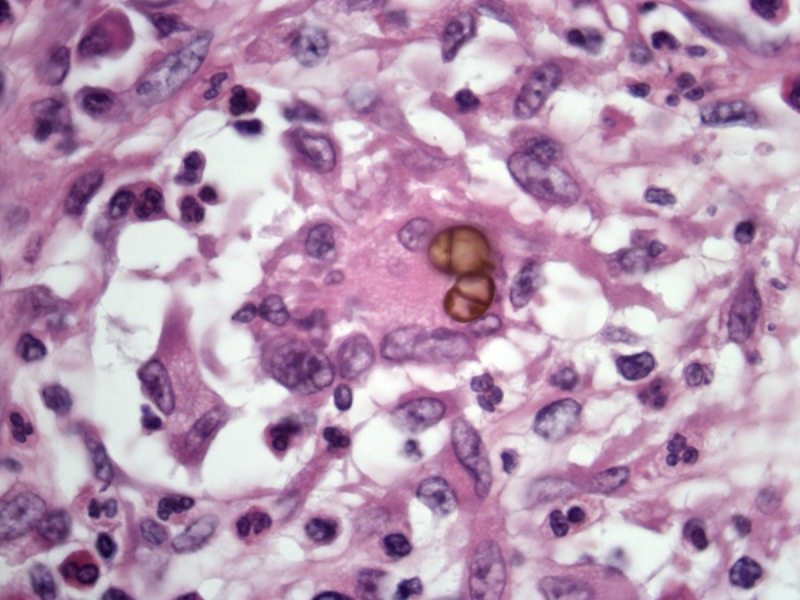

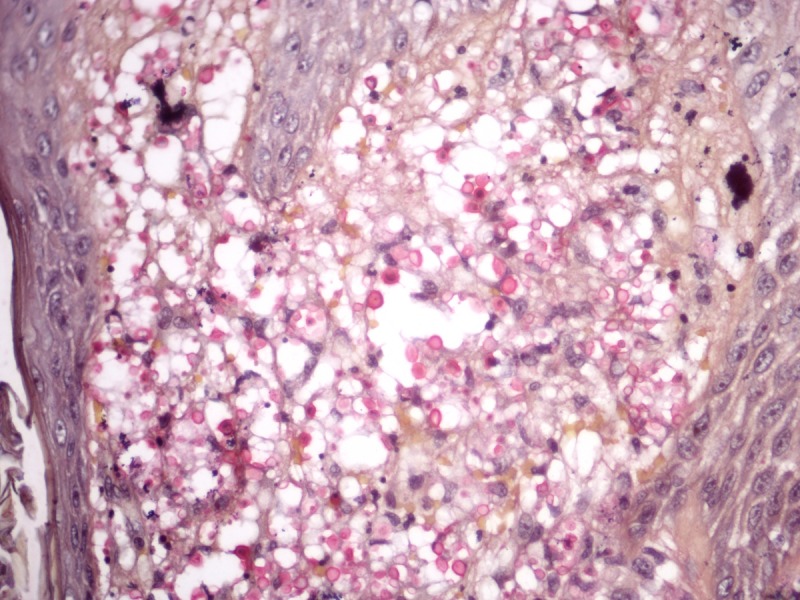

Figure 3.

Histopathology of a lesion from the left leg. Periodic acid-Schiff, 400 and 1000×. [Copyright: ©2013 Jeunon et al.]

Answer

Lobomycosis (Jorge Lobo’s disease)

Discussion

Lobomycosis is a chronic infectious granulomatous disease of the dermis and hypodermis caused by the fungus Lacazia loboi [1,2]. There is no involvement of internal organs or external mucosas, but regional lymph nodes may be affected in 10–25% of the cases. [1] It mainly affects adult males living in densely forested tropical areas that are in close contact with nature, such as farmers, tree tappers, miners, and workers of aquatic environments [1,3]. The original description of the disease by Jorge Lobo dates from 1930 and most cases have been reported in the northern Brazil, other countries of the Amazon region, Central America and Mexico. There have also been sporadic reports of the disease in United States, Europe and Canada, but at least some of these patients had been in South or Central America. Two autochthonous cases were recently reported in South Africa [4].

The fungus is supposed to live as a saprophyte in the soil, plants and water, but has never been cultured [1,3,5]. It has similarities to Paracoccidioides brasiliensis and some experts advocate that the name Lacazia loboi should replaced by Paracoccidioides loboi [6,7].

The infection is acquired by traumatic inoculation or contact of contaminated material with injured skin [1,2]. There is no transmission of the disease between humans, except for some reports of voluntary inoculation or inadvertent surgical contamination [7,8,9]. The infection has been documented in dolphins with the same presentation seen in humans.

The lesions are polymorphic and may present as papules, nodules, warty plaques and ulcers. Confluent keloid-like lesions in the legs, arms or ears are the most characteristic clinical scenario [1,3]. The clinical differential diagnosis is broad, including chromomycosis, lepromatous leprosy, anergic cutaneous American leishmaniasis, sporotrichosis, para-coccidioidomycosis, lymphedema (elephantiasis verrucosa nostra), Kaposi’s sarcoma, lymphomas, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, other sarcomas and metastasis [1,7,10]. However, the clinical diagnosis is not challenging for dermatologists of endemic areas, considering the morphology of the lesions, epidemiology and clinical course.

Recognition of the fungus through histopathology or direct cytology is essential for diagnostic confirmation, since cultivation methods are not available. The characteristic histopathological pattern is a nodular or diffuse inflammatory infiltrate made of epithelioid histiocytes and giant cells of Langhans or foreign-body types intermingled by collagen bundles. There is a thin band of collagen between the infiltrate and a flattened and bulged epidermis (grenz zone). In contrast to other, cutaneous/subcutaneous and deep mycoses, there are no areas of necrosis or suppuration, nor pseudocarcinomatous hyperplasia of the epidermis, unless the biopsy is taken at the edges of an ulcer. The fungus is abundant and easily seen in hematoxylin and eosin stained sections, mostly inside the histiocytes, but also in an extracellular fashion. Schiff’s-periodic acid or Grocott’s stains highlight the fungal elements. Lacazia loboi presents in tissue as numerous uniformly sized, yeast-like, large (8–12 μm, average 10 μm) spherical structures with a thick birefringent wall. The reproduction is done by simple budding, with both mother and daughter-cells having approximately the same size. The arrangement of the yeasts in chains of 2–10 cells is a characteristic feature [11,12].

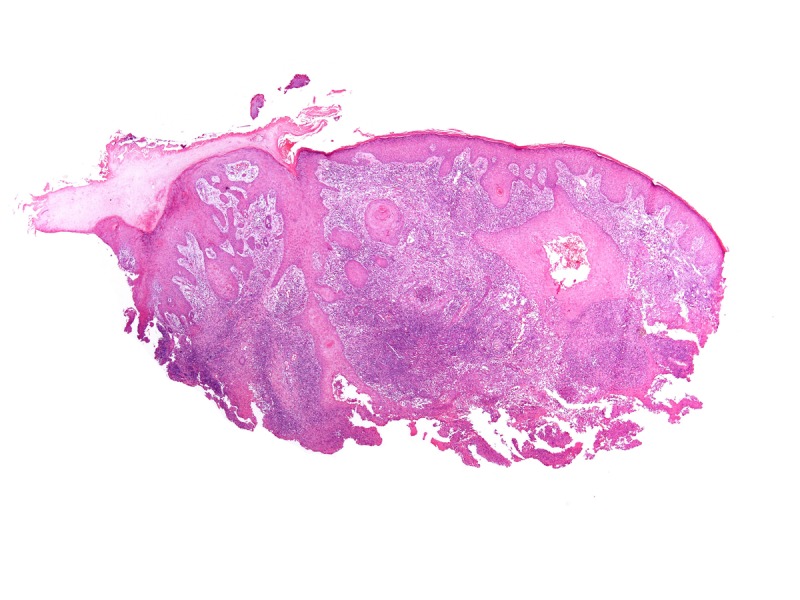

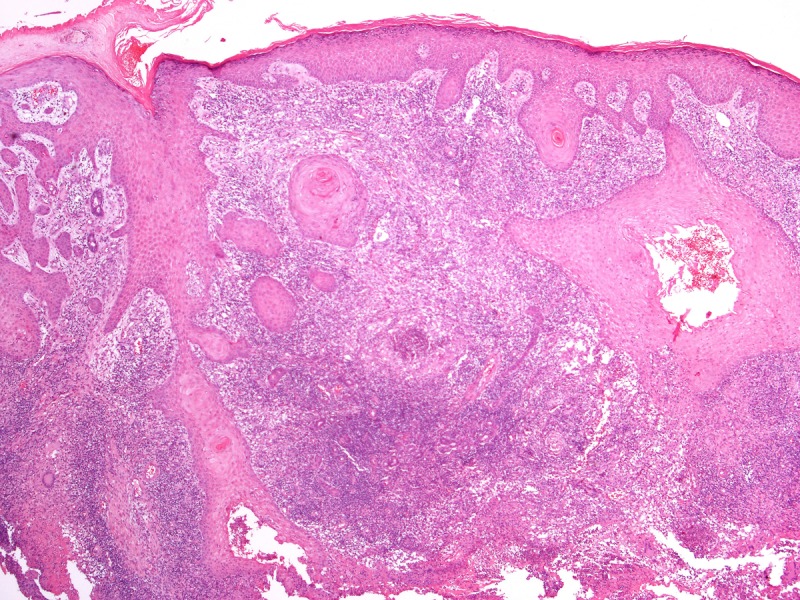

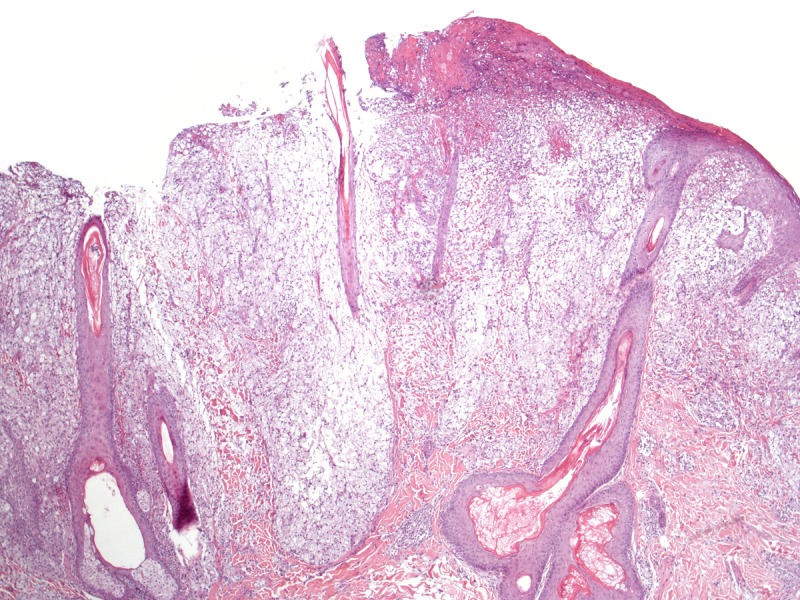

The histopathological differential diagnosis encompasses other mycoses in which the fungus assumes the form of yeasts. Most of dermal/subcutaneous and deep mycoses such as paracoccidiodomycosis, sporotrichosis, histoplasmosis and chromomycosis display a common pattern of tissue reaction characterized by suppurative granulomas in the dermis and pseudocarcinomatous hyperplasia of the epidermis. Eventually, some mycobacteriosis may share the same architecture (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Pseudocarcinomatous hyperplasia of the epidermis and anexa epithelium in conjunction with supurative granulomas in the dermis. This tissue reaction pattern is found in most of the subcutaneous/deep mycosis. H&E, 20, 100, 200 and 400×. [Copyright: ©2013 Jeunon et al.]

In paracoccidiodomycosis, the yeasts are similar to the ones seen in lobomycosis, with birefringent thick walls, but varying markedly in size, ranging from 5–20 μm [13]. The distribution of the daughter-cells budding on the surface of the mother-cells gives rise to the “steering wheel” or “Mickey-mouse” appearance (Figure 5). Daughter-cells may be many times smaller than the mother-cells, in contrast to lobomycosis.

Figure 5.

Paracoccidioidomycosis. (A) Variably sized yests inside a multinucleated giant cells. H&E, 1000×. (B, C) Large yeasts with multiple budding reproduction. Note that dauther-cells are much smaller than mother-cells. Grocott’s stain, 1000×. [Copyright: ©2013 Jeunon et al.]

In sporotrichosis, the fungus is not found in tissue in approximately 65% of cases [14]. Actually, in endemic areas of sporotrichosis, the diagnosis is highly suspected when the architectural pattern of deep mycosis is present in a section of tissue and no microorganism can be found. In such cases, the diagnosis is made by cultivation of the fungus, which grows in approximately 5 days. When viewed in tissue, Sporothrix schenckii typically presents as yeasts measuring 4–6 μm and some characteristic cigar-shaped elongated unicellular structures (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Sporotrichosis. Round yeasts and some elongated cigar--shaped fungal elements. Grocott’s stain, 1000×. [Copyright: ©2013 Jeunon et al.]

Histoplasma capsulatum is an obligatory intracellular parasite and is found in the skin as numerous tiny (2–4 μm) yeasts inside hystiocytes (Figure 7) [11].

Figure 7.

Histoplasmosis. Numerous small yeasts inside the cytoplasm of hystiocytes. H&E, 400 and 1000×. [Copyright: ©2013 Jeunon et al.]

Chromomycosis is easily differentiated from lobomycosis because the yeasts are pigmented, and reproduction is done by septation of the yeasts in steady of budding (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Chromomycosis. Dark-brown yeasts with reproduction by intracellular wall formation (septation). H&E, 400 and 1000×. [Copyright: ©2013 Jeunon et al.]

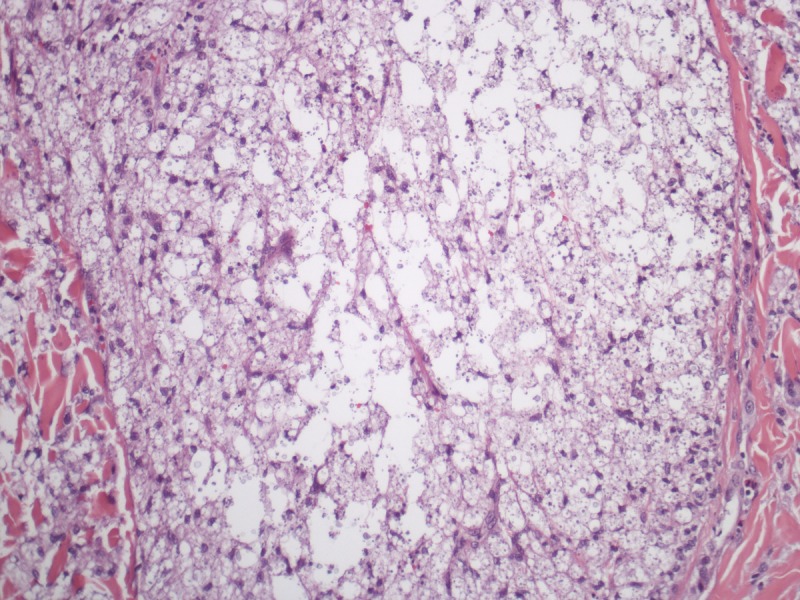

On the other hand, cryptococcosis usually has a general pattern dissimilar to the other mycoses. It presents as a diffuse “gelatinous” dermatitis made of pale histiocytes with large intracytoplasmic vacuoles containing one to several yeasts measuring 4–12 μm. The yeasts have cellular walls mostly composed of mucin, which make the fungi stain by colloidal iron, alcian blue or mucicarmine (Figure 9). In vivo, the cellular walls may be many times thicker than the diameter of the yeasts, occupying almost of the vacuoles inside histiocytes, but it shrinks during histological processing. In rare instances, cryptococcosis presents as a granulomatous and suppurative dermatitis in which fungal elements are small and do not stain for mucin. In such cases, the morphologic picture is quite similar to histoplasmosis and the recognition of Cryptococcus sp. in tissue is made by identification of small amounts of melanin in fungus yeasts by Fontana-Masson stain.

Figure 9.

Cryptococcosis. Multiple yeasts are present in large vacuoles inside pale staining hystiocytes. (A–C) H&E, 40, 100 and 1000×. (D) Mucicarmine, 400×. [Copyright: ©2013 Jeunon et al.]

Lobomycosis is a chronic disease with significant morbidity but is not life-threatening. The lesions slowly progress during years or decades just like in the case reported herein. The best chance of cure is achieved by surgical excision at the beginning of the disease when the patient has a single or just a few lesions. There is no effective chemotherapy available for extensive disease and standard anti-fungal agents usually have limited results. In this case, we used a combination of itraconazole and fluconazole for many months without significant improvement and proceeded with surgical excision of the most anesthetic lesions.

References

- 1.Talhari S, Talhari C. Lobomycosis. Clinics in Dermatology. 2012;30:420–4. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2011.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miranda MFR, Costa VS, Bittencourt MJS, Brito AC. Transepidermal elimination of parasites in Jorge Lobo’s disease. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85(1):39–43. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962010000100005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paniz-Mondolfi A, Talhari C, Hoffmann LS, et al. Lobomycosis: an emerging disease in humans and delphinidae. Mycoses. 2012;55:298–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2012.02184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Daraji WI, Husain E, Robson A. Lobomycosis in African patients. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:234–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Talhari C, Rabelo R, Nogueira L, et al. Lobomycosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85(2):239–40. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962010000200019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cardoso de Brito A, Quaresma JAS. Lacaziosis (Jorge Lobo's disease): review and update. An Bras Dermatol. 2007;82:461–74. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodríguez-Toro G. Lobomycosis. Int J Dermatol. 1993;35:324–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1993.tb01466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Azulay RD, Carneiro J de A, Andrade LC. Blastomicose de Jorge Lobo. Contribuição ao estudo da etiologia, inoculação experimental, imunologia e patologia da doença. An. Bras. Dermatol. 1970;45:47–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borelli D. Lobomicosis experimental. Derm Venez. 1962;3:72–82. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miranda MFR, Unger DAA, Brito AC, et al. Jorge Lobo’s disease with restricted labial presentation. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86(2):373–4. doi: 10.1590/s0365-05962011000200028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hinshaw M, Longley BJ. Fungal diseases. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson BL Jr, Murphy GF, Xu X, editors. Histopathology of the Skin. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2009. pp. 591–620. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weedon D. Mycoses and algal infections. In: Weedon D, editor. Skin Pathology. Edinburgh: Churchill-Livingston; 2002. pp. 659–90. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Binford CH, Dooley JR. Paracoccidioidomycosis. In: Binford CH, Connor DH, editors. Pathology of tropical and extraordinary diseases. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 1976. p. 567. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Quintella LP, Passos SRL, Francesconi do Vale AC, Galhardo MCG, Barros MBL, Cuzzi T, et al. Histopathology of cutaneous sporotrichosis in Rio de Janeiro: a series of 119 consecutives cases. J Cutan Pathol. 2011;38:25–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2010.01626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]