Abstract

Globally, both the incidence of type 2 diabetes and the consumption of meat, in particular pork meat, have increased, concurrently. Processed meats have been associated with an increased risk for diabetes in observational studies. Therefore, it is important to understand the possible mechanisms of this association and the impact of meats from different species. The goal of this systematic review was to assess experimental human studies of the impact of pork intake compared with other protein sources on early markers for the development of diabetes, ie, insulin resistance, glucose intolerance, and the components of the metabolic syndrome. A systematic review was conducted searching PubMed and EMBASE and using the Cochrane and PRISMA guidelines. Eight studies were eligible and critically reviewed. Five studies were based on a single meal or single day exposure to pork, as compared with other sources of protein. The glucose-insulin response following the pork meals did not differ compared with beef, shrimp, or mixed sources of proteins. However, compared with eggs, ham (processed meat) led to a larger insulin response in nonobese subjects. Compared with whey, ham led to a smaller insulin response and a larger glucose response. These findings suggest possible mechanisms for the association between processed meat and the development of diabetes. Nonprocessed pork meats were not compared with eggs or whey. The three longer interventions (11 days to 6 months) did not show a significant impact of pork on the components of the metabolic syndrome, with the exception of a possible benefit on waist circumference and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (one study each with significant limitations). Most of the findings are weak and there is a lack of solid evidence. The literature on the topic is limited and important research gaps are identified. Considering recent trends and projections for diabetes and pork intake, this is an important global public health question that requires more attention in order to provide improved evidence-based dietary recommendations.

Keywords: blood glucose, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, insulin resistance, meat, triglycerides, waist circumference

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes and the metabolic syndrome, also known as the insulin resistance syndrome or syndrome X, are significant public health problems in the US and globally. The metabolic syndrome is generally defined as a combination of increase in waist circumference, triglycerides, blood pressure, and blood glucose, and a decrease in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C).1 It is thought to be related to insulin resistance and development of type 2 diabetes.1 It has been estimated that, in 2008, 7.7% of US women and 8.1% of US men had diabetes.2 Furthermore, in the period of 1999–2006, 33.3% of US women and 34.9% of US men had insulin resistance syndrome.3 Globally, diabetes represented the ninth most frequent cause of death in 2010, up from the 15th most frequent cause in 1990,4 and diabetes mortality is projected to continue to increase significantly with the demographic and nutritional transitions taking place in large emerging countries, such as India and the People’s Republic of China.

Dietary habits are also changing. In the US, over the last 100 years, meat intake has significantly increased, primarily due to an increase in poultry consumption, with pork consumption remaining relatively constant and beef consumption decreasing slightly.5,6 However, since 2010, meat consumption has declined in the US, partially due to the economic slowdown, but is projected to rebound in 10 years to levels higher than the 2010 levels.7 Globally, meat intake has also increased significantly, in particular consumption of pork and poultry more than doubled in the last quarter of the 20th century in developing countries and is projected to continue to increase.8 Therefore, a better understanding of the association of diabetes with meat intake and different types of meat is an important global public health and agricultural policy question.

Several evidence-based dietary recommendations exist for the prevention and management of type 2 diabetes and the metabolic syndrome.9–11 The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends, for the prevention of type 2 diabetes among adults at risk of developing diabetes, referral “to an effective on going support program targeting weight loss of 7% of body weight”.11 For the management of adults who are already diabetic, the ADA recommends individualized medical nutrition therapy, preferably provided by a registered dietitian familiar with the components of diabetes medical nutrition therapy.11 The goals of diabetes medical nutrition therapy are to: monitor carbohydrates, limit intake of sugar-sweetened beverages, increase intake of dietary fiber to 14 g per 1,000 kcal, reduce intake of dietary fats, limit saturated fats to less than 7% of total calories, minimize intake of trans fats, and limit intake of alcohol to moderate amounts.11 No recommendations are made, however, on specific types of meats. For patients with diabetes and hypertension, the additional ADA recommendations are to implement a Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH)-style dietary pattern, including reducing sodium and increasing potassium intake.11 For patients with diabetes and dyslipidemia, the additional ADA recommendations are to reduce saturated fat, trans fat, and cholesterol intake, while increasing intake of n-3 fatty acids, viscous fibers, and plant stanols/sterols.11

An overarching recommendation for all overweight or obese diabetic patients is weight loss. The two approaches to weight loss recommended by the ADA are a low-carbohydrate, low-fat, calorie-restricted diet or Mediterranean diet, which have both been shown to have a positive effect on diabetes management.11 A low-carbohydrate, low-fat, calorie-restricted diet leads to an increased proportion of calories from protein, but the type of protein recommended is not specified. Because meat, an important source of protein in the US diet, has been associated in observational studies with increasing risk of diabetes,12–14 it is important to understand better the role that meat plays in weight loss for overweight diabetic patients, and, in general, for the management and prevention of type 2 diabetes.

The 2010 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee reported that “prospective cohort studies suggest that intake of animal protein products, mainly processed meat, may have a link to type 2 diabetes, although results are not consistent”.14 The committee noted that all five studies reporting on the relationship between intake of processed meats and type 2 diabetes found a positive association, while inconsistent findings were reported related to intake of red meat or poultry. A meta-analysis of observational studies published after this committee’s report confirmed a significant association of diabetes with processed, but not unprocessed meat, and that meats from different animal sources may be differently associated with diabetes.13 However, the mechanisms underlying this association are unclear. While food processing, fat content, and heme iron have been examined in some observational studies, less attention has been placed on the species of the animal source of the meat. Specifically, among red meats, pork has been shown to have different nutritional characteristics than other sources of meat and to be, for US fresh pork consumers, an important source of protein, selenium, thiamin, and vitamin B6.15 On a day of fresh pork consumption, these consumers also have lower intake of iron, an important micronutrient, but one that has been associated with an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes.16 The content of trans fat, another nutrient of concern in the management of diabetic patients, is lower in pork and chicken than in ruminant meats.17 On the other hand, much of the pork consumed in the US is in the form of processed meats, which have been associated with an increased risk for type 2 diabetes.13,14,18 Thus, the specific impact of pork meat on the risk and management of type 2 diabetes needs to be better understood to help in guiding consumers on optimal food choices. Furthermore, because observational studies are subject to residual confounding, it is also useful to examine human experimental studies that are less subject to confounding and provide a better understanding of potential mechanism of diabetes. Clinical studies have not been systematically reviewed on the specific topic of pork intake and diabetes. Therefore, the aim of this systematic review was to review experimental studies in humans of the impact of pork intake on the risk or management of type 2 diabetes or components of the metabolic syndrome, as compared with other sources of protein.

Materials and methods

This systematic review was conducted following the guidelines of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Review of Interventions and of the PRISMA statement.19–21 The review protocol, which is available online as additional material (see Supplementary material), was finalized on January 20, 2013 and, after testing the proposed search terms, revised on February 1, 2013. Because the number of publications available was unknown before the search, the aim was to review at first the association of the outcomes of interest with pork intake. If fewer than five studies had been identified, the search would have been expanded progressively to red meat; meat (red meat and poultry); meat or seafood; animal protein; or any protein until at least five studies were identified. The a priori study inclusion and exclusion criteria are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for publications

| Inclusion criteria |

| Clinical studies (randomized or not/controlled or before-after comparison) that include at least one intervention and published or prepublished (PubMed date) before 2013 |

| The intervention should consist of changes in consumption of pork and meat products containing at least 50% pork (when this information is available) |

| The intervention can be of any duration or frequency, including a onetime exposure |

| The study was performed in humans of any age, race, ethnicity, and medical condition |

| The associations between pork intake and health outcomes are reported |

| At least one of the reported outcomes is directly related to diabetes risk, management, or complications, including insulin resistance, glucose tolerance, glycemic control, or the metabolic syndrome |

| Publication is in the english language |

| Exclusion criteria |

| The publication is not on the topic of interest |

| The publication does not contain original data (most reviews and editorials) |

| The publication describes ambiguous methods or results are presented in a form that does not allow data extraction; the authors have been contacted, but sufficient data were not provided |

| The intervention related to pork is only part of other interventions (other dietary components, other lifestyles or drug interventions) |

| The outcomes are only subjective (quality of life, clinician perception) |

Literature search

Both PubMed and EMBASE databases were used to perform the literature search. For PubMed, the final combination of search terms was: (“Diabetes Mellitus”[Mesh] OR “Hyperglycemia”[Mesh] OR “Blood Glucose”[Mesh] OR “Insulin/blood”[Mesh] OR “Insulin Resistance”[Mesh] OR Diabetes OR Diabetic OR Prediabet* OR Hyperglycemi* OR “Glucose Tolerant” OR “Glucose Tolerance” OR “Glucose Intolerant” OR “Glucose Intolerance” OR “Insulin Resistant” OR “Insulin Resistance” OR “Metabolic Syndrome” or “Syndrome X”) AND (“Meat”[Mesh] OR Meat*[Title/Abstract] OR Pork[Title/Abstract] OR Bacon[Title/Abstract] OR Ham[Title/Abstract] OR Hams[Title/Abstract] OR Sausage*[Title/Abstract] OR “Hot Dog*”[Title/Abstract] OR Frankfurter*[Title/Abstract] OR Lunchmeat*[Title/Abstract] OR Salami[Title/Abstract] OR Pepperoni[Title/Abstract] OR Prosciutto[Title/Abstract] OR Pancetta[Title/Abstract]) Filters: Humans; English. Note that, after pretesting the key words, some of the free text terms were restricted to title or abstract content to avoid a large number of publications with an author or a city with the same name. Search terms or phrases which were not similar to last names or cities were not restricted to title or abstract in order to capture as many relevant articles as possible. The search was limited to studies published in 2012 or before, with no lower bound. For EMBASE, the following combination of search terms was used with the same publication time restriction: “diabetes mellitus”/exp OR “diabetes”/exp OR “hyperglycemia”/exp OR “hyperglycemic” OR “glucose intolerance”/exp OR “glucose intolerant” OR “insulin resistance”/exp OR “insulin resistant” OR “prediabetes”/exp OR “prediabetic” OR “metabolic syndrome”/exp AND (“meat”/exp OR “pork”/exp OR “bacon” OR “frankfurter” OR “hot dog” OR “lunchmeat” OR “ham” OR “sausage”/exp OR “salami” OR “pepperoni” OR “prosciutto” OR “pancetta”) AND [humans]/lim AND [english]/lim AND [embase]/lim.

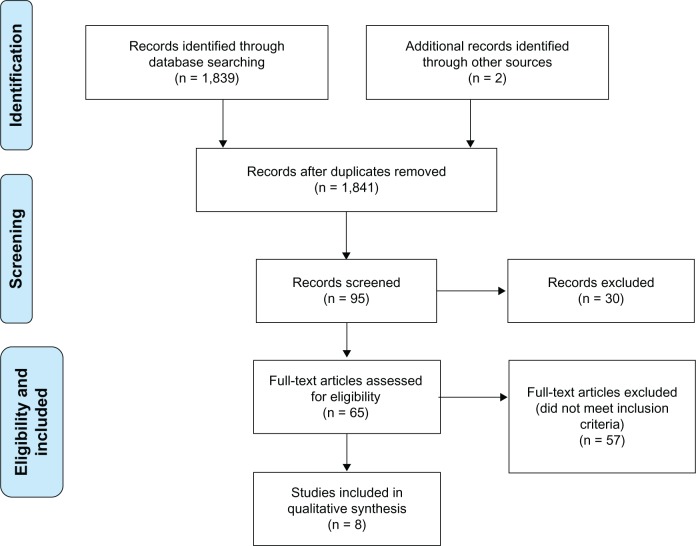

The title and, when available and necessary, abstract of each identified publication was reviewed independently by two of the authors (MMM, KMS). Records that did not meet the inclusion or exclusion criteria in Table 1 were excluded. Full texts were requested for publications that were not excluded in the first screening step and further reviewed by the two independent reviewers (Figure 1). Discrepancies were resolved by consensus or by a third author (NS).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart.

Data abstraction

Data abstraction was performed independently by two of the authors (MMM, KMS), using the following fields, modified for the aims of the present review from the Cochrane guidelines:19 study identification (ID), reviewer ID, citation, study design, total study duration, randomization procedure, blinding, total study population, age, gender, study setting and country, major inclusion/exclusion criteria, total number of intervention groups, specific intervention(s), intervention details, outcomes measured and timing, outcomes definitions, participants in each intervention group, missing participants, results by outcome, other (not specified a priori) outcomes, study authors’ conclusions, other study authors’ comments, reference to other relevant studies, and funding source. When the publications did not report some of the information that was to be extracted, locating and contacting the corresponding author of these publications was attempted and clarification was sought. When the study’s corresponding author replied and provided additional information, this information was included in the abstraction form. Additionally, the studies reviewers’ comments, questions asked of the study authors, and any additional analyses based on the provided data were recorded.

Results

Eight clinical studies were identified, including three with medium-term interventions (more than a week)22–24 and five with short-term interventions (single day or single meal per condition).25–29 Table 2 presents a summary of the study population, intervention, and findings of the eight studies, which are also briefy described below. Table 3 provides an overview of the comparison condition for each study.

Table 2.

Clinical studies of effects of pork on glucose, insulin, or metabolic syndrome components

| Reference | Study design | Total study population (n), country | Specific intervention(s) | Duration per intervention | Intervention details | Outcome measures and timing | Results by outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flynn et al23 | Crossover intervention followed by nonrandomized intervention | 76 healthy adults (47 M, 29 F), aged 32–62 years US | Beef Combined poultry and fish; Pork (final intervention for all subjects) |

Three-month diet interventions and a 6-week ad libitum period between the second and third interventions | Subjects were provided five edible ounces of raw meat of specified intervention type per day; could eat more of the same type of meat, but no meat of other types. each participant consumed one egg daily. | Fasting blood sample for analysis of TG and HDL-C at baseline, after 3 months, after 6 months, at baseline after 6-week runin period, and at the end of the pork intervention. | Insulin: – a Glucose: – HDL-C: reportedly differences by meat type, though specific differences not identified. Increased HDL-C after pork compared with prepork consumption baseline, but no statistical comparisons TG: no significant difference WC: – BP: – |

| Villaume et al26 | Crossover intervention | Eight normal weight adults (7 M, 1 F), mean age 30.1 ± 11.2 years France | Hamb Boiled egg |

Breakfast on 2 days | Ham or egg provided in isocaloric breakfast along with coffee, sucrose, white bread, and butter. Breakfast consumed after overnight fast. | Blood drawn before and at 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 40, 50, 65, 90, 120, 150, 180, 210, and 240 minutes after breakfast for measurement of blood glucose and plasma insulin response at each time and AUC. | Insulin: higher AUC after ham versus egg (AUC: 10,827 ± 1,273 versus 9,216 ± 1,010 μU · min/L, P < 0.025); higher response at 90 and 120 minutes with ham versus egg Glucose: no significant difference in AUC, higher response at 30, 40, and 50 minutes after ham versus egg, and lower response after ham versus egg at 150, 180, 210, and 240 minutes HDL-C: – TG: – wC: – BP: - |

| Villaume et al27 | Crossover intervention | Eleven obese adults (5 M, 6 F), mean age 45.3 ± 11.0 years France | Hamb Boiled egg |

Breakfast on 2 days | Ham or egg provided in isocaloric breakfast along with coffee, sucrose, white bread, and butter. Breakfast consumed after overnight fast. | Blood drawn before and at 5, 10, 15, 20, 30, 40, 50, 65, 90, 120, 150, 180, 210, and 240 minutes after breakfast for measurement of blood glucose and plasma insulin response at each time. | Insulin: no significant difference Glucose: higher response at 15, 20, 30, and 180 minutes after ham versus egg HDL-C: – TG: – WC: – BP: – |

| Chu et al22 | Crossover intervention | Thirteen healthy adults (5 M, 8 F); 23–43 years, diverse ethnic backgrounds US | Porkb Beefb Fish Soy Poultryb |

Eleven-day intervention per protein source | Three meals a day provided at the research facility; subjects free-living. intervention meats provided in lunch and dinner meals. isocaloric meals provided for each subject to meet his/her caloric needs. Three meals/day consumed at the research facility. | Mean fasting blood levels of glucose, TG, HDL at baseline and end of intervention, also change from baseline to end of intervention. | Insulin: – Glucose: no significant difference HDL-C: no significant difference TG: no significant difference WC: – BP: – |

| Chan et al29 | Crossover intervention | 24 Chinese adults with diabetes (19 M, 5 F), mean age 55.3 ± 12.5 years, 8 of whom consumed pork People’s Republic of China | Porridge with lean pork Porridge with shrimp Shao Mai Other paired comparison groups (total of 6 arms) |

Meals on 2 days, within one week | Eight subjects consumed test breakfast meal on two separate occasions within one week; no glucose medications on testing days. | Blood drawn before (0) and each 30 minutes through 240 minutes after breakfast for measurement of blood glucose AUC. | Insulin: – Glucose: no significant difference HDL-C: – TG: – WC: – BP: – |

| Frid et al25 | Crossover intervention | Fourteen adults with type 2 diabetes, presumably not taking medication for diabetes (8 M, 6 F), age 27–69 years Sweden | Lean hamb with lactose Whey powder |

Meals on 2 days, at least one week apart | Subjects consumed a breakfast of bread and whey or bread, ham and lactose followed by a lunch of mashed potatoes, meatballs, and whey or mashed potatoes, meatballs, ham, and lactose. Meals provided equal amounts of protein, lactose, and total carbohydrates. | Blood drawn before (0) and at 10, 20, 30, 40, 60, 120, 180, and 240 minutes after breakfast for measurement of blood glucose AUC and plasma insulin AUC response; lunch consumed after the 240 min blood draw, followed by blood draws at 10, 20, 30, 40, 60, 120, and 180 min for AUC measurements. | Insulin: lower after ham versus whey following both breakfast and lunch meals (37.5 ± 5.7 versus 44.3 ± 6.1 nmol · min/L, and 21.5 ± 3.3 versus 32.1 ± 4.2 nmol · min/L, respectively, P < 0.05; AUC from 0–180 minutes) Glucose: no significant difference after breakfast; higher after ham versus whey following lunch (403 ± 35.0 versus 320 ± 35.5 mmol · min/L, P < 0.05; AUC from 0–180 minutes) HDL-C: – TG: – WC: – BP: – |

| Charlton et al28 | Crossover intervention | 30 women, mean age 27.4 ± 8.2 years Australia | Pork Beef Chicken |

Breakfast on 3 days | Consumed isocaloric test meal with test meat (140 g) in a toasted sandwich in random order after an overnight fast (minimum 12 hours). | Blood drawn before (0) and at 15, 30, 60, 90, 120, 150, and 180 minutes after test meal for measurement of blood glucose AUC and plasma insulin AUC response. | Insulin: no significant difference Glucose: no significant difference HDL-C: – TG: – WC: – BP: – (pork: n = 29, beef, chicken: n = 26) |

| Murphy et al24 | Randomized controlled trial | 164 overweight/obese adults (M/F not specified), mean age 48 ± 12 years Australia | Pork diet Control diet | 6 months | Subjects on pork diet (n = 84) consumed 150 g servings (seven per week for men, five per week for women) of lean fresh pork in addition to other protein sources, control subjects (n = 80) maintained typical diet (less than pork serving per week). Seventy-two subjects completed in each group. | Fasting blood drawn at baseline, 3 and 6 months for measurement of plasma glucose and insulin, TG, and HDL-cholesterol; BP and WC also measured. | Insulin: no significant difference Glucose: no significant difference HDL-C: no significant difference TG: no significant difference WC: lower in pork group at 6 months (P < 0.01) BP: no significant difference. |

Notes:

Endpoint not examined

processed products (sausage, lunch meat).

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the curve; BP, blood pressure; F, female; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; M, male; TG, triglycerides; WC, waist circumference.

Table 3.

Comparison groups in clinical studies of effects of pork on glucose and insulin or metabolic risk factors

| Reference | Duration per intervention | Pork (form) | Mixed diet | Beef | Poultry | Fish/shellfish | Egg | Soy | Whey |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Murphy et al24 | Six months | • (P and F)a | • | ||||||

| Flynn et al23 | Three months | • (F) | • | •b | •b | ||||

| Chu et al22 | Eleven days | • (P) | • | • | • | • | |||

| Villaume et al26 | Single meal | • (P) | • | ||||||

| Villaume et al27 | Single meal | • (P) | • | ||||||

| Frid et al25 | Two consecutive meals | • (P) | • | ||||||

| Charlton et al28 | Single meal | • (F) | • | • | |||||

| Chan et al29 | Single meal | • (Fc) | • |

Notes:

Processed (includes ham, sausage, luncheon meat)

Combined poultry and fish

assumes “lean pork” to be fresh pork.

Abbreviations: P, processed (includes ham, sausage, luncheon meat); F, fresh.

Medium-term interventions

Three of the identified studies included a dietary intervention to increase pork intake, as compared with other protein sources, for 11 days,22 3 months,23 or 6 months.24

In a randomized controlled study, Murphy et al studied the effects of increased consumption of lean pork on body composition and cardiovascular risk factors.24 Overweight adults were randomized to consume five (women) or seven (men) 150 g servings of pork per week as part of their otherwise typical diet (pork group, n = 84) or to continue consuming their normal diet (control group, n = 80). No attempt was made to keep diets isocaloric between groups. Subjects in the pork group met with study personnel every 2 weeks to monitor body weight and collect frozen pork products for consumption during the study. Subjects in the control group were only followed up with phone calls at an unspecified frequency to discuss progress. A total of 72 subjects completed the study in each group. At the end of the 6-month intervention, there were no significant differences between the two groups for glucose, insulin, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, HDL-C, or triglycerides. The change in waist circumference was, however, significantly different between the groups, with a mean decrease from baseline to 6 months of approximately 0.6 cm in the pork group and an increase of approximately 0.8 cm in the control group (P < 0.01). Body weight decreased in the pork group but increased in the control group. The authors concluded that “Regular consumption of lean fresh pork may improve body composition”. This study suggests a benefit of pork on waist circumference, one of the components of the metabolic syndrome. However, a major limitation is that subjects in the pork group had more in-person contact than subjects in the control group, which could explain, in part, why the pork group was more successful in controlling weight and waist circumference.

Flynn et al conducted a crossover intervention study to compare the effects of beef, combined poultry and fish, or pork on blood lipids.23 A total of 76 adults completed all three interventions. During each intervention, subjects were provided with five edible ounces of raw meat (beef, poultry/fish, pork) per day. Interestingly, baseline triglycerides and HDL-C levels prior to any intervention were significantly different from values after the washout period prior to the pork intervention. The investigators reported that, based on analysis of variance, only HDL-C differed significantly across the meat intervention groups, with “inconsistent changes both upward and downward”. No additional details of the analysis or results were provided. However, in all four study subject groups (as defined by gender and whether beef was consumed in the first or second intervention), HDL-C levels at the end of the pork intervention were 3–7 mg/100 mL higher than levels at the beginning of the pork consumption period, suggesting a positive impact of pork intake on HDL-C.

Using a crossover study design, Chu et al assessed the effects of five protein sources (pork, beef, fish, soybean, and poultry) on protein balance and lipid levels.22 Thirteen healthy adults were enrolled in the 55-day study. During each of five 11-day periods, the subjects consumed in random order a diet with one of the five protein sources. The pork, beef, and soybean diets provided significantly less protein than the fish and poultry diets, while the pork diet provided significantly less fat than the beef diet though more fat than the fish, soybean, and poultry diets. All meals were consumed at the research facility. Across the five test diets or compared with baseline, there were no significant differences in fasting measures of glucose, HDL-C, or triglycerides.

Short-term interventions

Five studies examined the effects of pork consumed as part of a meal; four studies measured post-prandial blood insulin and glucose responses,25–28 and one study measured only the post-prandial glucose response.29

Frid et al compared the effects of whey or pork proteins consumed as part of high glycemic index meals on subsequent blood insulin and glucose levels.25 Fourteen adults diagnosed with type 2 diabetes were enrolled in this crossover study. On one occasion following an overnight fast, the subjects consumed a breakfast consisting of bread, ham, and lactose dissolved in water. Four hours later, they consumed a lunch consisting of mashed potatoes, meatballs, ham, and lactose dissolved in water. On the other test occasion, subjects consumed a combination of lactose and whey dissolved in water in place of the ham at breakfast and lunch. The ham-based and whey-based meals delivered equal amounts of carbohydrate, protein, lactose, and liquid matched by meal occasion (breakfast, lunch). Compared with fasting baseline levels, incremental glucose and insulin area under the curve (AUC) were calculated for the 3 hours following each meal. The insulin AUC response following ham consumption was significantly less than following whey consumption. The glucose AUC did not differ following breakfast with ham or whey, but the glucose AUC after a lunch including ham was significantly higher than after a lunch including whey. Results from this study indicate that ham produces a smaller post-meal insulin response than whey, while the effects on glucose are inconsistent.

Villaume et al conducted two studies using a similar crossover design to assess the effects of pork compared with egg proteins on plasma glucose and insulin responses. Eight nonobese healthy adults participated in the first study.26 Following an overnight fast, the subjects consumed in random order a breakfast including either ham or hard-boiled egg. The insulin 4-hour AUC was significantly higher after the ham than after egg. There was no difference in the blood glucose AUC response after the ham-based and egg-based meals. However, following the ham-based meal, blood glucose levels were significantly higher at 30, 40, and 50 minutes and significantly lower at 150, 180, 210, and 240 minutes compared with the egg-based meal (P < 0.05). Overall, in these nonobese subjects, ham appeared to stimulate the insulin response more than egg. The overall glucose response was the same between the two protein sources, but the timing was different, with an earlier increase with ham than with egg.

The study was repeated in 11 obese adults.27 In these subjects, no significant differences in insulin levels following the meals containing ham or egg were observed. Glucose levels at 15, 20, 30, and 180 minutes following the ham-containing meal were significantly higher than following the egg-containing meal (P < 0.05). The authors did not report the insulin or glucose AUC values.

Charlton et al studied the effect of different protein sources consumed at breakfast on acute satiety and appetite hormones in 30 women using a crossover design.28 On three separate days following an overnight fast, each participant consumed in random order a toasted breakfast sandwich made with pork, beef, or chicken. The test meals were matched for carbohydrate and protein, while fat content was 14% higher in the chicken meal than in the pork and beef meals. Measurements were completed for 29 women after the pork test meal and for 26 women after the beef and chicken test meals. No significant differences in the insulin or glucose 3-hour AUC were observed between the protein sources.

Chan et al compared the glucose responses of diabetic adults following consumption of various traditional Chinese foods.29 Following an overnight fast, eight of the subjects consumed porridge with pork or with shrimp Shao Mai on two separate mornings. The meals were matched for protein and carbohydrate, but differed in fat; the fat content of the shrimp-containing meal was 21.3 g versus 1.6 g in the pork meal. Glucose 4-hour AUC responses did not differ significantly between the pork-based and shrimp-based meals.

Discussion

This systematic review of the human experimental studies of the impact of pork compared with other protein sources on glucose/insulin metabolism or the metabolic syndrome components reveals largely inconclusive findings due to limitations in design or data analyses. These limitations include heterogeneity in the comparison interventions, duration of the interventions, and small sample size. Considering the global public health importance of the question and suggestions by observational studies of an increased risk for diabetes with increasing processed meat consumption,13,14 this topic requires increased attention. However, despite these limitations, a few trends and suggestive findings can be noted.

Regarding the impact of pork as compared with other protein sources on the insulin and glucose responses to a meal standardized for carbohydrates, this review suggests that pork-based protein sources result in responses that are similar to beef, chicken, shrimp, or a mixed source of protein in the diet.22,24,28,29 In three of these four studies, pork was consumed exclusively or predominantly in the form of fresh cooked pork, while in the fourth study,22 in which no difference was observed either, processed meats were used for pork and the other conditions. In three of the remaining four studies,25–27 pork was provided in processed form and differences between the pork and other protein sources were observed. As compared with eggs, pork in the form of ham appears to result in a larger insulin response with no difference in glucose response.26 This effect seems to be limited to nonobese subjects, and suggests decreased insulin sensitivity associated with pork, in this case processed pork. These findings could partially explain the association between processed meat and diabetes described in observational studies.13,14 Alternatively, these findings could be explained by a decrease in insulin clearing or an increase in the nonbioactive form of insulin. As compared with whey, processed pork in the form of ham led to a lower insulin response and a higher glucose response.25 However, it is unclear if this difference is due to the source of protein or to the meat processing necessary to produce ham, as would be suggested by observational studies.13,14 None of the reviewed studies compared fresh pork with egg or whey.

Regarding the impact of pork intake on components of the metabolic syndrome, no clear difference appears compared with other sources of protein, with the possible exception of waist circumference and HDL-C. Promotion of increased pork intake appears to have a beneficial impact on waist circumference, probably due to the impact on weight. However, the findings of this single study are limited by the fact that subjects in the pork group but not the control group had frequent contact with the research team, which is a key component of a successful weight loss program.30 Most of the reviewed studies did not show differences in HDL-C between pork and other sources of protein,22,24 except for one study that suggested a possible increase in HDL-C above baseline levels following medium-term pork intake.23 However, the design and analysis limitations of this study require that this finding be reproduced.

Based on the present review, several clinical research gaps can be identified to improve the scientific basis of dietary recommendations and consumer choices. Short-term intervention studies aimed at clarifying the acute impact of fresh pork intake on glucose-insulin metabolism, as compared with processed pork and other sources of protein, such as other meats, egg, whey, or plant-based proteins, would be useful. They would improve the understanding of possible mechanisms underlying the association observed in epidemiologic studies between meat intake and development of diabetes. The positive impact of a medium-term increase in pork intake on waist circumference and body weight is intriguing,24 but needs to be reproduced in randomized studies that are not limited by other differences between interventions. Similarly, the increase in HDL-C after pork intake is interesting,23 but should be reproduced in studies designed to test this specific hypothesis. Furthermore, more homogenous study designs and standardized outcomes could generate findings that are more useful for making recommendations to the general population. Long-term epidemiologic studies that differentiate the type, cut, and processing of meat could also provide additional evidence.

Weaknesses of the present review include its limited scope of pork intake and diabetes or the metabolic syndrome; however, the criteria to limit this scope were specified a priori and, for systematic reviews, fidelity to prespecified criteria is critical to validity.19 Another limitation is the heterogeneity in comparison groups, study designs, study quality, and outcomes present in the current clinical research literature. While PubMed and EMBASE were used to identify relevant publications, some studies may have been missed if they did not appear in these two databases, but in other databases, such as the Cochrane Library. Strengths of the present review include its adherence to a predefined and publicly available protocol, and the fact that the study selection and extraction processes were conducted in duplicate by two independent researchers.

Conclusion

In conclusion, experimental studies in humans designed to test the impact of pork intake on glucose-insulin metabolism, markers of metabolic syndrome, or mechanisms leading to the development of diabetes are limited, but, in general, suggest no differences compared with other sources of protein. The limited evidence suggests a possible negative impact of processed pork on glucose-insulin metabolism and a possible positive impact of pork intake on waist circumference and HDL-C, but significant research gaps exist, preventing the drawing of definite conclusions. Considering the global increase in pork intake and diabetes, this topic requires increased attention.

Footnotes

Disclosure

This project was funded by the National Pork Board. The study sponsor had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing the report, or the decision to submit the report for publication. Otherwise, the authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120(16):1640–1645. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beckles GL, Zhu J, Moonesinghe R, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Diabetes – United States, 2004 and 2008. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2011;60(Suppl):90–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mozumdar A, Liguori G. Persistent increase of prevalence of metabolic syndrome among US adults: NHANES III to NHANES 1999–2006. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(1):216–219. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2095–2128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walker P, Rhubart-Berg P, McKenzie S, Kelling K, Lawrence RS. Public health implications of meat production and consumption. Public Health Nutr. 2005;8(4):348–356. doi: 10.1079/phn2005727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daniel CR, Cross AJ, Koebnick C, Sinha R. Trends in meat consumption in the USA. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14(4):575–583. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010002077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Office of the Chief Economist World Agricultural Outlook Board. US Department of Agriculture USDA Agricultural Projections to 2021–2012 Available from: http://www.usda.gov/oce/commodity/archive_projections/USDAAgriculturalProjections2021.pdfAccessed August 7, 2013

- 8.Delgado CL. Rising consumption of meat and milk in developing countries has created a new food revolution. J Nutr. 2003;133(Suppl 2):3907S–3910S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.11.3907S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krauss RM, Eckel RH, Howard B, et al. Revision 2000: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Nutrition Committee of the American Heart Association. J Nutr. 2001;131(1):132–146. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.1.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases What I need to know about eating and diabetes 2007Available from: http://diabetes.niddk.nih.gov/dm/pubs/eating_ez/Eating_Diabetes.pdfAccessed August 7, 2013

- 11.American Diabetes Association Standards of medical care in diabetes – 2013. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(Suppl 1):S11–S66. doi: 10.2337/dc13-S011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Neil CE, Keast DR, Fulgoni VL, Nicklas TA. Food sources of energy and nutrients among adults in the US: NHANES 2003–2006. Nutrients. 2012;4(12):2097–2120. doi: 10.3390/nu4122097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feskens EJ, Sluik D, van Woudenbergh GJ. Meat consumption, diabetes, and its complications. Curr Diab Rep. 2013;13(2):298–306. doi: 10.1007/s11892-013-0365-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.US Department of Agriculture. Human Nutrition Information Service. Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, United States. Agricultural Research Service . Report of the Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee on the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010: to the Secretary of Agriculture and the Secretary of Health and Human Services. Washington, DC: United States Department of Agriculture, United States Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murphy MM, Spungen JH, Bi X, Barraj LM. Fresh and fresh lean pork are substantial sources of key nutrients when these products are consumed by adults in the United States. Nutr Res. 2011;31(10):776–783. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao Z, Li S, Liu G, et al. Body iron stores and heme-iron intake in relation to risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. 2012;7(7):e41641. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aro A, Antoine JM, Pizzoferrato L, Reykdal O, van Poppel G. Transfatty acids in dairy and meat products from 14 European countries: the TRANSFAIR study. J Food Compost Anal. 1998;11(2):150–160. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis CG, Lin BH. Factors Affecting US Pork Consumption. Washington, DC: US Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higgins JPT, Green S, Cochrane Collaboration . Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chu FL, Kies C, Clemens ET. Studies of human diets with pork, beef, fish, soybean, and poultry: nitrogen and fat utilization, and blood serum chemistry. J Appl Nutr. 1995;47(3):51–66. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flynn MA, Naumann HD, Nolph GB, Krause G, Ellersieck M. Dietary “meats” and serum lipids. Am J Clin Nutr. 1982;35(5):935–942. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/35.5.935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murphy KJ, Thomson RL, Coates AM, Buckley JD, Howe PR. Effects of eating fresh lean pork on cardiometabolic health parameters. Nutrients. 2012;4(7):711–723. doi: 10.3390/nu4070711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frid AH, Nilsson M, Holst JJ, Bjorck IM. Effect of whey on blood glucose and insulin responses to composite breakfast and lunch meals in type 2 diabetic subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82(1):69–75. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.82.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Villaume C, Beck B, Rohr R, Pointel JP, Debry G. Effect of exchange of ham for boiled egg on plasma glucose and insulin responses to breakfast in normal subjects. Diabetes Care. 1986;9(1):46–49. doi: 10.2337/diacare.9.1.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Villaume C, Beck B, Barthelemy N, Rohr R, Debry G. Variability of blood glucose and plasma insulin responses after replacing ham by egg in the breakfast of obese subjects. Nutr Res. 1988;8(6):605–615. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Charlton KE, Tapsell LC, Batterham MJ, et al. Pork, beef and chicken have similar effects on acute satiety and hormonal markers of appetite. Appetite. 2011;56(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chan EM, Cheng WM, Tiu SC, Wong LL. Postprandial glucose response to Chinese foods in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104(12):1854–1858. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wadden TA, Webb VL, Moran CH, Bailer BA. Lifestyle modification for obesity: new developments in diet, physical activity, and behavior therapy. Circulation. 2012;125(9):1157–1170. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.039453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]