Abstract

Background

Malignant bowel obstruction is a common result of end-stage abdominal cancer that is a treatment dilemma for many physicians. Little has been reported predicting outcomes or determining the role of surgical intervention. We sought to review our experience with surgical and nonsurgical management of malignant bowel obstruction to identify predictors of 30-day mortality and of who would most likely benefit from surgical intervention.

Methods

A chart review of 523 patients treated between 2000 and 2007 with malignant bowel obstruction were evaluated for factors present at admission to determine return to oral intake, 30-day mortality, and overall survival. Propensity score matching was used to homogenize patients treated with and without surgery to identify those who would benefit most from operative intervention.

Results

Radiographic evidence of large bowel obstruction was predictive of return to oral intake. Hypoalbuminemia and radiographic evidence of ascites or carcinomatosis were all predictive of increased 30-day mortality and overall survival. A nomogram of 5 identified risk factors correlated with increased 30-day mortality independent of therapy. Patients with large bowel or partial small bowel obstruction benefited most from surgery. A second nomogram was created from 4 identified risk factors that revealed which patients with complete small bowel obstruction might benefit from surgery.

Conclusion

Two nomograms were created that may guide decisions in the care of patients with malignant bowel obstruction. These nomograms are able to predict 30-day mortality and who may benefit from surgery for small bowel obstruction.

Malignant Bowel Obstruction (MBO) is a common occurrence in patients with end-stage intra-abdominal malignancies. MBO is most commonly associated with ovarian and colorectal cancers, carrying a 5–50% and 10–28% risk of development over the course of these diseases, respectively.1,2 All terminally ill cancer patients have a 3–15% risk of developing MBO during the course of disease, including extra-abdominal cancers, such as breast cancer and melanoma.3,4

MBO typically conveys a dismal prognosis, with an estimated life expectancy of 1–9 months.5-8 The impact of a malignancy-induced bowel obstruction versus a benign cause in patients is dramatic, with an 80% decreased survival rate for those who had tumor as the origin of their bowel obstruction.6 A high rate of morbidity is often associated with this diagnosis because the patients often suffer prolonged and worsening nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain until they reach the point of seeking medical intervention.1,9,10 Of the patients who are able to leave the hospital after treatment for MBO (∼75%), more than half will return with recurrent bowel obstructions.7 Given the universally poor prognosis and the often debilitated state of the patients at presentation, treatment strategies limiting morbidity and mortality are imperative.

Patients with MBO share the condition of a noncurable, intra-abdominal malignancy, but the exact cause of the bowel obstruction may vary from true mechanical obstruction to adynamic ileus or constipation.1,9-11 A universal treatment regimen is therefore not appropriate. Modern therapy options include pharmacotherapy to reduce gastrointestinal secretions with anticholinergics and somatostatin receptor agonists (eg, octreotide) and with antiemetics, narcotics, and occasionally corticosteroids.3,8,10,12,13 Endoscopic therapies, such as decompressive percutaneous endoscopic-assisted gastrostomy tube placement and stenting have utility in select patients.1,3,10,14,15 These endoscopic interventions are limited by the length the scopes can reach, the length of the obstruction, and by alterations in anatomy.1 The deployment of stents is possible in about 90% of attempts, but has a perforation risk of 7–14% and a failure rate of 25–30%.16,17 Stents are often not permanent solutions and are best used as a bridge therapy to allow patients to receive surgical intervention.18,19 Stents have also been shown to be equivalent to emergency surgery for large bowel obstruction.17

The third interventional option for many may be surgical management, which may include bowel resection, stoma creation, bowel bypass, adhesiolysis, or a combination thereof.4 There are risks with surgical interventions for patients with MBOs, including morbidity (45–78%) and a high mortality (10–12%).17,18 There are benefits that only surgery can allow for patients that makes surgery an option for palliation of patients with malignant bowel obstruction. In patients with colorectal malignancies, surgery for malignant bowel obstruction not only provides adequate palliation, but was able to facilitate the use of palliative chemotherapy, which improved overall survival.20 In bowel obstruction secondary to advanced ovarian cancer, surgery was found to be a durable palliation that improved survival for patients when compared to those receiving endoscopic interventions.21 Finally, surgery is able to reach all portions of the bowel from esophagus to anus, unlike endoscopic interventions.

While surgery does have a role in this population, it is appropriate for only a subset of patients. Several factors have been found to improve outcomes from surgical intervention for MBO and include the absence of ascites,22-24 a good performance status,25 low blood urea nitrogen,25 a high albumin level,25 absences of carcinomatosis,23 and only 1 obstructive point along the alimentary tract.23 These factors have been determined from several small studies that only examined patients who were treated with surgical therapy because randomized, controlled trials in this patient population are almost impossible to conduct.10,13

In this study, we evaluated the management and outcomes for patients with MBO who underwent either surgical or nonsurgical therapy. Our goal in undertaking this study was to identify predictors of return of bowel function and survival so as to develop a scoring system that can be used to delineate patients who may or may not benefit from surgical intervention.

Methods

This retrospective study was approved by the institutional review board of the Ohio State University. A list was compiled of all patients presenting to the Ohio State University Medical Center system with the diagnoses of a solid tumor malignancy and bowel obstruction between the years of 2000 and 2007. Subjects were included in the study if they had an intra-abdominal cancer that was unresectable for cure and obstructed at any location along the gastrointestinal tract from the pylorus to the anus as diagnosed clinically or by radiologic imaging. We excluded patients with a tumor amenable to potentially curative therapy and patients who had a history of admission for MBO. The first admission to our institution was considered the index admission for this study.

Data obtained from the medical records for each individual included age, gender, specific cancer diagnosis, type of therapy (surgical versus nonsurgical), initial laboratory values for white blood cell count (WBC) and serum albumin, and radiographic findings. Cancer diagnoses were divided into 6 categories: colorectal, gynecologic, genitourinary, neuroendocrine, and noncolorectal gastrointestinal. Radiographic findings before the initiation of therapy included for analysis were intra-abdominal mass, carcinomatosis, complete small bowel obstruction, partial small bowel obstruction, large bowel obstruction, and ascites. Five outcomes were documented: return to oral intake before discharge, duration of hospital stay, time to recurrent bowel obstruction, 30-day mortality, and overall survival.

The initial evaluation of the compiled data divided patients into 2 groups based on the type of therapy during that admission. Nonsurgical therapy consisted of medical, temporary decompression (ie, nasogastric tube) and endoscopic procedures (eg, stenting, percutaneous endoscopic-assisted gastrostomy tube). Surgical therapy consisted of any nonendoscopic procedure undertaken in the operating room for the purpose of bowel obstruction relief. The groups were compared with the Fisher exact or Student t tests where appropriate.

To evaluate factors as potential predictors of outcome from MBO, the entire cohort of patients were evaluated as one. All clinical variables were considered in the univariate analysis for 30-day mortality and return to oral intake. The same variables were entered stepwise into a multivariate model based upon their degree of contribution. After the model was built, factors no longer significant were removed and the model was rerun. Kaplan–Meier survival curves were constructed and compared by log rank analysis. Cox proportional hazards using all variables were conducted in a stepwise fashion to determine those factors significant for overall survival. All analyses were undertaken using (SPSS) software (version 19; SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL).

Factors found to be significantly correlated with 30-day mortality were then used to create a scoring system to predict survival for patients presenting with MBO regardless of therapy. Groupings by score were analyzed for significance by chi-square analysis.

A subgroup created by propensity scoring was then analyzed to determine factors that could delineate who would benefit from surgical more than nonsurgical means. Propensity scoring was used because of the heterogeneity of these patients as a whole; by creating smaller, more evenly matched groups, additional analysis could create more meaningful factors that would help determine differences in outcomes between the 2 treatment groups. Eight factors were used to characterize these patients (age, gender, carcinomatosis, complete small bowel obstruction, ascites on imaging, leukocytosis, hypoalbuminemia, and cancer type). Once these were determined, a second scoring system was created to determine who would benefit from surgical intervention when presenting with MBO.

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) unless stated otherwise. P ≤ .05 was considered significant.

Results

Study population

During the study period, 2,380 admissions for 1,857 cancer patients with a diagnosis of obstruction of any type were compiled. Of these, 523 met the above stated criteria and were included in the study. Reasons for excluding patients included no documented obstruction either radiographically or in the patient electronic medical record, nonbowel obstructions (urinary, etc), non–solid tumor malignancy, previous bowel obstruction (before the study period or at another hospital), and resectable primary tumor as cause of obstruction. There were 324 patients treated with surgical therapy, and 199 were treated by nonsurgical means. Demographics for these 2 groups were similar except that a significantly greater number of males underwent surgical therapy (Table I). Cancer diagnosis was also similar between the groups except for a significantly greater amount of gynecologic cancers in the nonsurgical group. Admission laboratory values for the patients consisted of WBC and serum albumin at the time of admission. WBC measurements were not significantly different between the 2 groups, but average albumin levels were significantly higher in the surgical patients. Based upon radiographic imaging at the time of admission, patients who underwent surgery were more likely to present with a distinct intra-abdominal mass and/or large bowel obstruction and less likely to have findings of complete small bowel obstruction, carcinomatosis, and/or significant ascites (Table I).

Table I. Demographic, cancer diagnoses, laboratory values, and radiographic findings for all 523 patients based upon surgical or nonsurgical management.

| Management | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Nonsurgical (n = 199) | Surgical (n =324) | P value | |

| Mean age (yrs), range | 58.6 (29–86) | 60.1 (28–89) | .200 |

| Males | 59 (29.7%) | 158 (48.8%) | .015 |

| Cancer diagnosis* | |||

| Colorectal | 54 (27.1%) | 124 (38.3%) | .071 |

| Gynecologic | 72 (36.2%) | 57 (17.6%) | <.001 |

| Genitourinary | 10 (5%) | 28 (8.6%) | .167 |

| Other GI (noncolorectal) | 30 (15.1%) | 38 (11.7%) | .356 |

| Carcinoid | 8 (4%) | 29 (9%) | .052 |

| Other | 27 (13.6%) | 51 (15.7%) | .617 |

| WBC (×103/mm3) | 9.7 ± 6.9 | 10.2 ± 5.9 | .334 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.7 ± 0.7 | 3.0 ± 0.8 | .001 |

| Radiographic imaging† | |||

| Carcinomatosis | 111 (55.8%) | 69 (21.3%) | <.001 |

| Mass | 44 (22.1%) | 118 (36.1%) | .014 |

| Partial SBO | 51 (26.1%) | 67 (21.0%) | .300 |

| SBO | 124 (62.3%) | 127 (39.2%) | .003 |

| LBO | 16 (8.0%) | 49 (15.1%) | .040 |

| Any ascites | 73 (36.7%) | 91 (27.8%) | .142 |

| Moderate/large ascites | 56 (28.1%) | 46 (14.2%) | .020 |

Numbers and percentages do not add up to 100% because several patients had 2 simultaneous cancers at the time of presentation.

Numbers and percentages do not add up to 100% because of multiple radiographic findings in some patients.

GI, Gastrointestinal; LBO, large bowel obstruction; SBO, small bowel obstruction; WBC, white blood cell.

Disposition and mortality

Data on disposition at discharge was available for 518 (98%) patients and divided into 4 categories: home (with or without nursing care), extended care facility, hospice (as inpatient or outpatient), or death during the index hospitalization (Table II). The majority of patients were able to return to home without immediate plans for hospice, regardless of therapy. However, discharge to an extended care facility was more common after surgical management, while discharge to hospice was more frequent in nonsurgical patients. Death during the index admission was identical between the 2 groups (6.6%).

Table II. A comparison of the disposition and outcomes after initial hospitalization for patients with malignant bowel obstruction treated with surgical or nonsurgical means.

| Type of management | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Nonsurgical (n = 199) | Surgical (n = 324) | P value | |

| Disposition* | |||

| Home (with or without nursing care) | 124 (62.9%) | 223 (70.1%) | .473 |

| Extended care facility | 19 (9.6%) | 53 (16.7%) | .051 |

| Hospice (in- or outpatient) | 41 (20.8%) | 22 (6.9%) | .001 |

| In-hospital death | 13 (6.6%) | 21 (6.6%) | 1 |

| Return to oral intake at discharge† | 145/181 (80.1%) | 233/290 (80.3%) | 1 |

| Duration of hospital stay (days) | 8.4 ± 7.8 | 15.6 ± 11 | <.001 |

| Reobstruction† | 70/199 (35.2%) | 58/324 (17.9%) | <.001 |

| Time to reobstruction (days) | 36.4 ± 67.9 | 222.5 ± 294.5 | <.001 |

| 30-day mortality† | 67/183 (36.6%) | 67/251 (26.7%) | .360 |

| Duration of survival (days)‡ | 173.69 ± 377.3 | 331.21 ± 466.5 | <.001 |

Disposition data available for 197 patients managed nonoperatively and 319 treated with surgery.

Denominator denotes number of patients for whom data was available.

Actual time from discharge to death.

Return to oral intake was successful by the time of discharge in the vast majority of patients in both groups (Table II). However, the duration of stay was almost twice as long in the surgical group. Of note, the average time from admission to surgery was 4.5 days. Therefore, the duration of hospitalization after surgery was 11 days vs 8.4 days for the nonsurgical patients (P <.001). Conversely, re-obstruction was twice as common when patients were managed nonoperatively (P <.001). When re-obstruction did occur, it was typically much later in the patients' courses than if the index obstruction had been managed nonoperatively (222 days vs 36 days). Death at 30 days was similar between the 2 groups.

Return to oral intake

Univariate regression analysis identified hypoalbuminema (<3 g/dL), the presence of carcinomatosis on radiographic imaging, and large bowel obstruction on imaging were significantly associated with a decreased return to oral intake. On multivariate analysis, large bowel obstruction on radiographic imaging was associated with successful return to oral intake at discharge (odds ratio [OR], 4.97; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.13–21.9; P = .034; Table III).

Table III. Univariate and multivariate analysis of factors associated with return to oral intake by the time of discharge.

| P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Factor | Univariate | Multivariate | Multivariate OR (95% CI) |

| Albumin <3 g/dL | .039 | .160 | |

| Ascites | .192 | .567 | |

| Carcinomatosis | .009 | .153 | |

| Cancer diagnosis | .534 | .779 | |

| Nonsurgical therapy | .690 | .460 | |

| LBO | .022 | .034 | 4.97 (1.1–21.9) |

| Leukocytosis | .001 | .083 | |

| Mass | .170 | .160 | |

| SBO | .154 | .170 | |

CI, Confidence interval; LBO, large bowel obstruction; OR, odds ratio; SBO, small bowel obstruction.

Thirty-day mortality

We next sought to identify predictors of early (ie, 30-day) mortality. Univariate factors of hypoalbuminemia, the presence of ascites on imaging, carcinomatosis on radiography, nonsurgical therapy, and leukocytosis were all associated with an increased 30-day mortality, while neuroendocrine carcinoma was associated with a decreased 30-day mortality (Table IV). Hypoalbuminemia, ascites, and carcinomatosis remained significant predictors of 30-day mortality on multivariate analysis (Table IV).

Table IV. Univariate and multivariate analysis of factors associated with 30-day mortality.

| P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Factor | Univariate | Multivariate | Multivariate OR (95% CI) |

| Albumin <3 g/dL | <.001 | <.001 | 2.91 (1.72–4.93) |

| Ascites | <.001 | .008 | 2.00 (1.20–3.33) |

| Carcinomatosis | <.001 | .019 | 1.84 (1.11–3.06) |

| Cancer diagnosis | .041 | .059 | |

| Nonsurgical therapy | .003 | .202 | |

| Return of oral intake | .412 | — | |

| SBO | .190 | .644 | |

| Leukocytosis | .001 | .070 | |

| Mass | .886 | .616 | |

| LBO | .919 | .376 | |

CI, Confidence interval; LBO, large bowel obstruction; OR, odds ratio; SBO, small bowel obstruction.

Overall survival

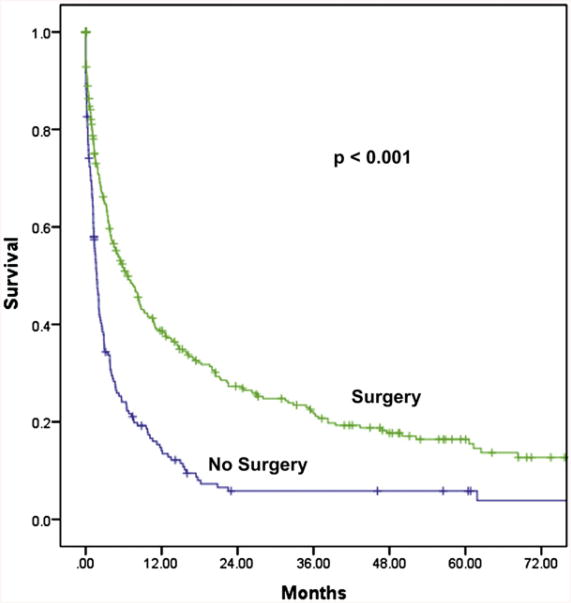

Overall survival for all patients was median 3.8 months. Survival for those who underwent surgery was longer than those who received nonoperative therapy (median, 6.6 months vs 1.7 months; P < .001; Fig 1). Univariate predictors of overall survival included ascites on imaging, hypoalbuminemia, WBC, carcinomatosis on computed tomographic scan, cancer type, and surgical intervention (for all P < .001).

Fig 1.

Kaplan–Meier overall survival curves of surgical versus nonsurgical therapy for the entire cohort of 523 patients (P < .001).

On multivariate analysis, predictors of poor survival were hypoalbuminemia (OR, 1.60; 95% CI, 1.24–2.05; P < .001), the presence of ascites on radiographic imaging (OR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.09–1.85; P = .01), carcinomatosis on imaging (OR, 1.47; 95% CI, 1.10–1.95; P = .009), and the diagnosis of a genitourinary cancer (OR, 2.22; 95% CI, 1.30–3.79; P = .004). Surgery (OR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.55–0.96; P = .026) and the diagnosis of a neuroendocrine malignancy (OR, 0.36; 95% CI, 0.20–0.65; P = .001) where shown to be associated with an improvement in survival.

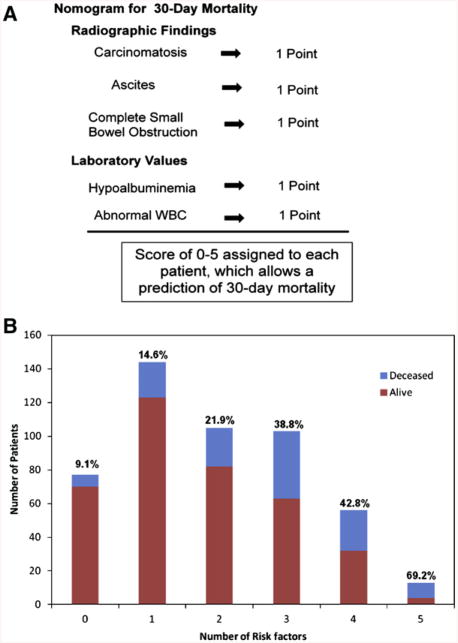

Scoring system for short-term prognosis

A nomogram scoring system was developed from factors that correlated with increased 30-day mortality to create a tool to determine short-term mortality for those patients presenting with MBO independent of therapy. Five factors found to be predictors of 30-day mortality were assigned a value of 1 if present or 0 if not. A score of 0–5 was then assigned to each patient based on the sum of these factors. Using the 5 risk factors of ascites, carcinomatosis, complete small bowel obstruction on imaging, hypoalbuminemia, and abnormal WBC, we evaluated 30-day mortality for the 498 patients with MBO who had a known survival status at 30-days (Fig 2, A). While a majority of the patients had 0–2 risk factors, more than 30% of patients presenting with MBOs had ≥3 risk factors (Fig 2, B). Patients who had no risk factors present at the time of admission had the lowest mortality rate. Mortality increased significantly as the number of risk factors increased (P < .001; Fig 2, B).

Fig 2.

(A) Nomogram to estimate 30-day mortality for patients presenting with malignant bowel obstructions independent of therapy. One point was assigned for each of the 5 variables. (B) The distribution of 523 patients with malignant bowel obstruction for each number of risk factors contributing to 30-day mortality. The blue portion of the bar represents the number of patients alive at 30 days and the red represents the number of patients who were dead at 30 days. The percentage above each bar is the percentage dead at 30 days. (Color version of figure is available online.)

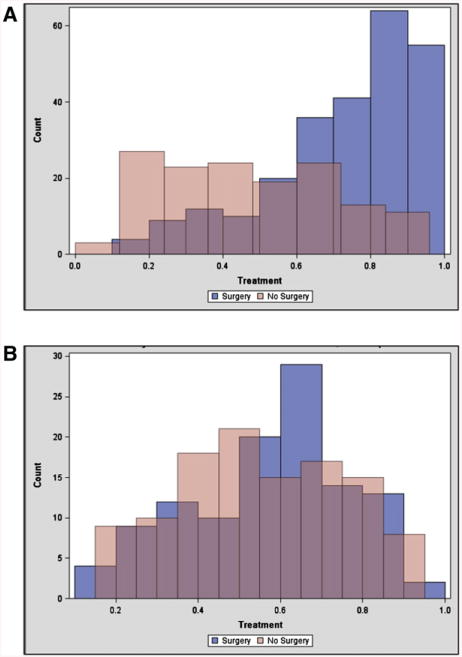

Scoring system for surgical benefit

Once a nomogram was established to aid in predicting those with poor short-term survival, we established a second scoring system to aid in determining which patients with an acceptable short-term survival would benefit from surgery. To do so, a comparison between those treated surgically and nonsurgically was required. As stated above, there were considerable differences between these 2 groups that would make attempt at determining prognostic factors difficult (Tables I and II; Fig 3, A). Therefore, propensity scoring was implemented with 8 factors as described in the methods. This resulted in a subgroup of 226 patients (113 per group) that were more similar (Fig 3, B; Table V).

Fig 3.

Propensity score matching based upon the characteristics of age, gender, the presence of carcinomatosis, the presence of complete small bowel obstruction, the presence of ascites on imaging, leukocytosis, hypoalbuminemia, and cancer diagnosis. (A) Representative of the patients from the entire cohort who had data for each factor (n = 395), which showed very little overlap between the 2 groups. (B) Representation of the population (n = 226) created after propensity scoring was conducted to produce more comparable groups. (Color version of figure is available online.)

Table V. Frequency of 8 characteristics used for propensity scoring between the 2 comparison groups.

| Surgery (n = 113) | No surgery (n = 113) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD) | 59.0 (12.0) | 58.2 (12.8) |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 71 (62.8) | 76 (67.3) |

| Male | 42 (37.2) | 37 (32.7) |

| Carcinomatosis | ||

| No | 65 (57.5) | 57 (50.4) |

| Yes | 48 (42.5) | 56 (49.6) |

| Complete SBO | ||

| No | 49 (43.4) | 48 (42.5) |

| Yes | 64 (56.6) | 65 (57.5) |

| Ascites | ||

| No | 69 (61.1) | 70 (61.9) |

| Yes | 44 (38.9) | 43 (38.1) |

| High WBC | ||

| No | 78 (69.0) | 76 (67.3) |

| Yes | 35 (31.0) | 37 (32.7) |

| Low albumin | ||

| No | 47 (41.6) | 47 (41.6) |

| Yes | 66 (58.4) | 66 (58.4) |

| Cancer diagnosis | ||

| Colorectal | 27 (23.9) | 30 (26.5) |

| Gynecologic | 34 (30.1) | 37 (32.7) |

| GU | 6 (5.3) | 6 (5.3) |

| Other GI | 19 (16.8) | 19 (16.8) |

| Carcinoid | 6 (5.3) | 4 (3.5) |

| Other | 21 (18.6) | 17 (15.0) |

GI, Gastrointestinal; GU, genitourinary; SBO, small bowel obstruction; SD, standard deviation; WBC, white blood cell.

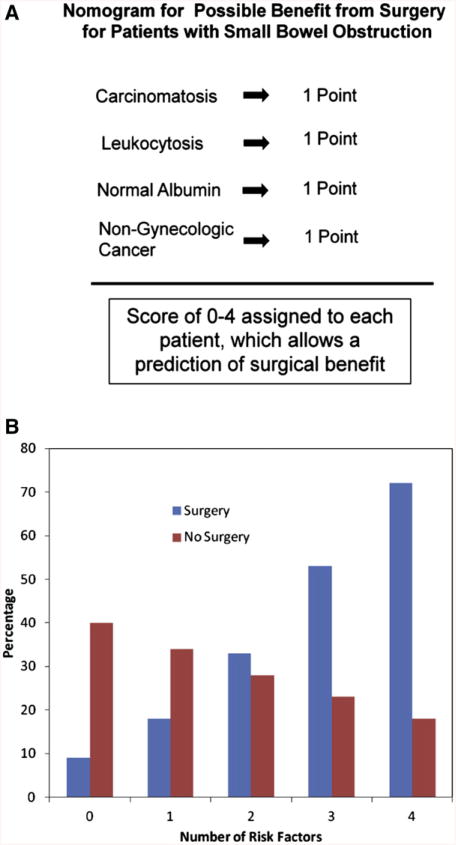

Once 2 comparable groups were determined, predictors of 30-day mortality with or without surgery were sought. Preliminary analysis revealed that the association of surgery in patients categorized as not having a complete small bowel obstruction (ie, large bowel or partial small bowel obstruction) with decreased 30-day mortality was fairly dramatic (OR, 0.11; 95% CI, 0.036–0.323). This influenced all analyses. Therefore, only complete small bowel obstruction patients (n = 130) were used to create the nomogram and considered separately in the final suggested treatment algorithm. This nomogram used the variables carcino-matosis on imaging, leukocytosis, normal albumin, and nongynecologic cancer. If any one of these were present they were assigned a score of 1. Patients were then assigned a total score of 0–4 that was then analyzed proportionally to determine the risk of 30-day mortality with or without surgery (Fig 4, A). From the actual data, the model was then able to generate a probability of 30-day mortality based on number of risk factors for each therapy.

Fig 4.

(A) Nomogram to estimate surgical benefit in patients with complete small bowel obstruction. One point was assigned for each of the 4 variables. (B) Thrity-day mortality based on the computer model created from the survival characteristics for surgery and nonsurgery patients based on the number of risk factors present. As the number of factors increase, the mortality from surgery increases, whereas an inverse correlation is seen for nonsurgical therapy. (Color version of figure is available online.)

In patients with complete small bowel obstruction on radiographic imaging, as the number of risk factors increased, the risk of 30-day mortality increased significantly and favored nonsurgical therapy (P = .038; Fig 4, B). When 0 or 1 risk factors were present, surgery improved 30-day mortality. However, when 4 or 5 were present, surgical management greatly increased 30-day mortality. Mortality was similar between operative and non-operative management when 2 factors were present.

In conclusion, the ideal management of patients with MBO is very difficult to delineate because of the variety of complex issues involved. Clinical decision-making must incorporate knowledge of tumor biology, the available remaining cancer treatment options, the psychology involved with the inability to eat and end-of-life considerations, along with the underlying health of the patient. While our study is not the first to analyze outcomes for patients with MBO, it is the largest to date and one of the first to incorporate both surgical and nonsurgical therapies.7,25 We attempted to use objective measures that can reliably be used in the decision-making process. By including both groups (surgical and nonsurgical) we are able to make outcome comparisons between the 2 treatment regimens, create a prognostic scoring system for all patients presenting with MBO, and evaluate when surgical intervention may provide the most benefit.

The risks and benefits of a treatment for MBO are the criteria used by physicians in determining the treatment to offer. The most common medical and psychological morbidity associated with MBO is the inability to tolerate food.1,10 Not surprisingly, we found that only large bowel obstruction seen on imaging (compared to small bowel obstruction) reliably predicted who would ultimately be able to return to oral intake. Other researchers have also shown that the presence of ascites and/or carcinomatosis reduce the likelihood of return to oral in-take.22 The difficulty with using this outcome in therapy in a retrospective review is the inability to clearly define successful return to oral intake. Given the subjective nature of “tolerating oral intake,” we focused on a more concrete endpoint of mortality on which to base our nomogram.

The results of our evaluation of both short-term (30-day mortality) and overall survival yielded more factors that were significant. Factors such as the presence of ascites and carcinomatosis conveyed a poor prognosis—a finding consistent with previos publications.22-24 Albumin was shown in our study and by others to be a predictor of survival.25 Leukocytosis was shown to be a marker of both short-term and overall survival. This has not been reported previously, but generally is a marker of acute illness, so intuitively fits with a patient who would have a poorer prognosis. The impact of cancer diagnosis on outcome mostly reflects patients with neuroendocrine tumors in the evaluation who have a much better survival than any of the other diagnoses. Nonsurgical therapy was shown to convey a poor prognosis in general. This was more likely a result of selection bias toward healthier patients being selected as surgical candidates. The propensity scoring used in the study was used as an attempt to homogenize our data set for the evaluation of when surgical intervention could be the most impactful.

To simplify the statistical analysis, we dichotomized the type of obstruction seen on initial imaging into complete small bowel obstruction versus partial small bowel obstruction or large bowel obstruction. As such, the latter group was clearly identified as those who were more likely to return to oral intake and who would benefit most from surgery. These results are likely related to the influence of large bowel obstruction more than the partial small bowel obstruction patients. We suspect that the difference observed in outcomes is related to the association of small bowel obstruction with carcinomatosis and multifocal obstruction, whereas large bowel obstruction is often caused by 1 mass that causes a more focal obstruction and is more amenable to upstream diversion. Dalal et al23 similarly identified multiple points of obstruction as being a poor prognostic factor.

The results of this study provide 2 tools that can be used in making decisions for the care of patients with MBO. The first tool is a short-term prognosis scoring system. This nomogram should be implemented early in the patient's presentation to the hospital because it may direct all subsequent care. By using the 5 commonly obtained values, a fairly straightforward 30-day mortality prediction can be made (Fig 2). For the patients that have scores of 4 or 5, their 30-day survival is often <60%. This prediction model allows for open and honest conversations with patients and their families as to realistic expectations moving forward, thereby allowing them to make informed decisions.

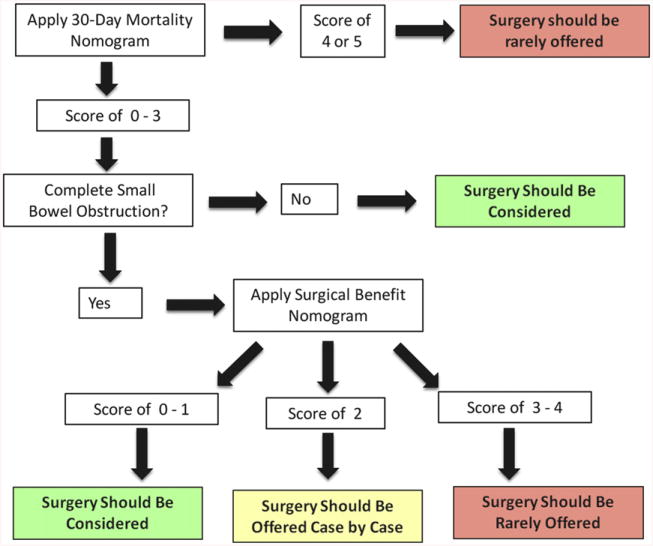

The second nomogram from this study helps to determine if surgery would provide a benefit. This system involves 2 steps. First, the type of bowel obstruction (complete small bowel versus partial small bowel or large bowel) must be determined through imaging. If the patient appears to have a large bowel obstruction, they should most likely be offered surgical intervention because this appears to offer a 10-fold greater chance of survival at 30 days. For the patients who appear to have a complete small bowel obstruction, the nomogram in Figure 4 applies. By looking at the 4 risk factors, a determination can be made if surgery would be beneficial. For those with scores of 0 or 1, surgery may be beneficial. A score of 2 is the equivalence point where surgery and nonsurgery are predicted to have similar outcomes. These patients must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis. Scores of 3 or 4 most likely would be best treated by nonsurgical therapy (Fig 5).

Fig 5.

An algorithm purposed for use of both scoring systems in patients with malignant bowel obstruction. (Color version of figure is available online.)

This study's greatest limitation is its retrospective nature. Although we attempt to objectify the process for selecting patients for operative versus nonoperative therapies, like so many studies in surgery we are unable to account for all possible variables. As such, we hope that this nomogram can be used in a prospective manner to validate our findings. Similar nomograms are frequently used in cancer care to select patients for treatments with curative intent. Such a tool would prove invaluable for patients at end-of-life, when the ramifications of surgical decision-making are paramount.

Despite its limitations, we hope this study will provide a potential guide for the treatment of a very complex patient population where standard treatment protocols are lacking. In our current practice, we use the factors associated in each nomogram to provide prognostic information during consultation for bowel obstruction in patients with a history of cancer. While the combination of both nomograms is useful in guiding surgical decision-making, they require validation and should not supersede sound clinical judgment. For example, in patients with peritonitis or signs of intra-abdominal catastrophe—where time for thorough work-up and consultation are limited—or in a patient with a large bowel obstruction amenable to stenting in the face of multiple other risk factors, the use of our nomograms may be less helpful. However, in more common situations where we are able to include the patient and their family in the decision-making process, we have found these nomograms to be quite useful, particularly for prognosis. We hope to validate these decisions prospectively.

Discussion

Dr Sam Pappas (Milwaukee, WI): I would like to thank the authors for providing me the manuscript in advance and to congratulate them on a well-designed trial of review of the management of malignant bowel obstruction (MBO) at their institution. As the presenter stated, the goal of this study was to identify predictors of return of bowel function and survival. And the results of this study provide 2 important nomograms that can be used to predict 30-day mortality and patients who may benefit from surgical intervention. I would like to just open the discussion with 2 very basic questions.

There was an obvious benefit to the patients who had large bowel obstruction that underwent surgical intervention. Can you comment on what you might think the role of nonoperative therapies at your institution is in light of these findings? For example, what's the role of endoluminal stenting in light of your most recent findings?

Secondly, can you comment further as to why you think the partial small bowel obstruction group did better than the complete bowel obstruction group?

Dr Jon Henry (Columbus, OH): So for your first question, I should clarify that, any endoscopic intervention, including percutaneous endoscopic-assisted gastrostomy tubes or stents, were placed in the nonsurgical group.

There were actually not many stents in that group, given the study period. We now more liberally utilize endoscopic stents, particularly for duodenal and distal colon and proximal rectal obstructions.

Now, in saying that, there's quite a plethora now of studies out there showing benefit of these stents. And so that may be, once again, on a case-by-case basis, but they're still not completely without risk, so are considered on a case-by-case basis in consultation between surgery and gastroenterology with the default being surgical intervention in the fittest patients.

For your second question, we dichotomized the data into small bowel obstruction versus not, which included both large bowel obstructions and partial small bowel obstructions.

What we are seeing with this is the large bowel obstructions are weighing heavily on this group and increasing the survival rate. The true incidence of the partial small bowel obstructions actually having better outcome is probably not as robust.

Dr Eugene Choi (Chicago, IL): It's probably one of the larger series that we have addressing MBO of 523 patients. In addition, it includes both surgical and nonsurgical management of patients in this paper. I think it reiterates some of the more depressing highlights of this particular problem in that, in their paper, the median survival for all these patients was 3.8—it's a little less than 4 months.

The question I had is that this was in patients at 1 institution. Of all these patients, which service did they go to? Were they on the surgical service? Did they come to a medical oncology service? And did that influence the treatment as to what they got in terms of their MBO?

Secondly, a lot of the patients with MBO usually present on the onset of symptoms within 6 weeks of actually having some kind of chemotherapy. And did that chemotherapy affect those patients who underwent surgery and what their results were?

And in terms of your nomogram, obviously, the patients who have 5 out of 5 of the negative risk factors—carcinomatosis, ascites, white blood cell count is up, obstruction—obviously, those patients are most often not treated surgically. In your review, the patients with low factors (1 factor, 2, or 3)—in terms of their assessment, what kind of treatment did they get?

Dr Jon Henry (Columbus, OH): Most of these patients were on surgical services but I can't give a definitive number. I will say that the vast majority of patients had surgical consultation very early in their hospital course. However, the average delay of 4 days until surgery likely reflects time spent on a non-surgical service.

As far as chemotherapy, that is a question we tried to address. The difficulty with our institution is that a lot of patients come to us for surgery but go other places for their chemotherapy. And so I tried to, but it was difficult getting that information, so I really can't answer that accurately for you.

As far as the nomogram, if I understand you correctly, what type of therapy the scores of 0–3 are getting versus the 4–5?

Dr Eugene Choi (Chicago, IL): Yeah, in your paper, when you look at the 30-day mortality of all comers in the patients you have assessed, those with factors <3, what kind of treatment did they receive and what were their outcomes?

Dr Jon Henry (Columbus, OH): Okay. So most of them received surgical therapy, if I'm answering this correctly for you. And we did not analyze that specific group, of just the 0–3 group. We have not looked at that specifically.

Dr Mark Malangoni (Philadelphia, PA): I think it's very helpful to all of us to understand when surgery doesn't work well. And you have made a fantastic point today.

I want to ask you a question, because, about 9 or 10 years ago, we presented a paper here, looking at small intestinal obstruction, all-cause, including malignant and nonmalignant diseases, and found that one of the factors that was associated with the short outcome differences, particularly complications and mortality, was patients that needed an intestinal resection or had an inadvertent enterotomy.

I wondered if you considered looking at those factors. I mean, obviously, those can't always be predicted ahead of time. So they may not be useful in what you have in discussions with your patients, but they're certainly something to consider when you're doing the operation.

Dr Jon Henry (Columbus, OH): We did not look specifically at the types of operations they all had. We did list them all, but we did not look at the outcomes of the patients that had small bowel resections or bypasses versus those that had large from the outcomes. As you alluded to, the intent of this paper was to use a priori data to predict the impact of surgical therapy as a whole on the ultimate outcome. I do think future studies from this data set may allow us to improve intraoperative decision making.

Dr Scott Wilhelm (Cleveland, OH): I have 1 comment and a question for you in regard to the way you applied your scoring system. You came out with all these data, and then you sort of took that data and looked back at your patients. That's a little bit of a problem when you're creating a scoring system, because you introduced a selection bias. You already selected out what patients were going to get operations, not get operations, and thus what their outcomes are.

So my question is, have you taken your scoring system and started looking prospectively now at any other patients you've operated on to see if it starts correlating with your data?

But it's a very nice start to a good background.

Dr Jon Henry (Columbus, OH): You've brought up a good point. That is our next step, and that's what we've kind of intended with this. There is not a lot of good retrospective reports on this. So that's what gave us the starting point. And, yes to really validate these nomo-grams, we need to start looking prospectively.

Acknowledgments

Dr Henry is supported by National Cancer Institute grant T32-60032104.

Footnotes

Presented at the 69th Annual Meeting of the Central Surgical Association, Madison, Wisconsin, March 1–3, 2012.

References

- 1.Dolan EA. Malignant bowel obstruction: a review of current treatment strategies. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2011;28:576–82. doi: 10.1177/1049909111406706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ripamonti C, Bruera E. Palliative management of malignant bowel obstruction. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2002;12:135–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1438.2002.01103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ripamonti CI, Easson AM, Gerdes H. Management of malignant bowel obstruction. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:1105–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong TH, Tan YM. Surgery for the palliation of intestinal obstruction in advanced abdominal malignancy. Singapore Med J. 2009;50:1139–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Selby D, Wright F, Stilos K, Daines P, Moravan V, Gill A, et al. Room for improvement? A quality-of-life assessment in patients with malignant bowel obstruction. Palliat Med. 2010;24:38–45. doi: 10.1177/0269216309346544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mirensky TL, Schuster KM, Ali UA, Reddy V, Schwartz PE, Longo WE. Outcomes of small bowel obstruction in patients with previous gynecologic malignancies. Am J Surg. 2012;203:472–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2011.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chakraborty A, Selby D, Gardiner K, Myers J, Moravan V, Wright F. Malignant bowel obstruction: natural history of a heterogeneous patient population followed prospectively over two years. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41:412–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baines M, Oliver DJ, Carter RL. Medical management of intestinal obstruction in patients with advanced malignant disease. A clinical and pathological study Lancet. 1985;2:990–3. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)90534-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ripamonti C, De Conno F, Ventafridda V, Rossi B, Baines MJ. Management of bowel obstruction in advanced and terminal cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 1993;4:15–21. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a058345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feuer DJ, Broadley KE, Shepherd JH, Barton DP. Surgery for the resolution of symptoms in malignant bowel obstruction in advanced gynaecological and gastrointestinal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;4:CD002764. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anthony T, Baron T, Mercadante S, Green S, Chi D, Cunningham J, et al. Report of the clinical protocol committee: development of randomized trials for malignant bowel obstruction. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34(1 Suppl):S49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Porzio G, Aielli F, Verna L, Galletti B, Shoja E, Razavi G, et al. Can malignant bowel obstruction in advanced cancer patients be treated at home? Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:431–3. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-1009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mercadante S, Casuccio A, Mangione S. Medical treatment for inoperable malignant bowel obstruction: a qualitative systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33:217–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ang SK, Shoemaker LK, Davis MP. Nausea and vomiting in advanced cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2010;27:219–25. doi: 10.1177/1049909110361228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soriano A, Davis MP. Malignant bowel obstruction: individualized treatment near the end of life. Cleve Clin J Med. 2011;78:197–206. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.78a.10052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Manes G, de Bellis M, Fuccio L, Repici A, Masci E, Ardiz-zone S, et al. Endoscopic palliation in patients with incurable malignant colorectal obstruction by means of self-expanding metal stent: analysis of results and predictors of outcomes in a large multicenter series. Arch Surg. 2011;146:1157–62. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Hooft JE, Bemelman WA, Oldenburg B, Marinelli AW, Holzik MF, Grubben MJ, et al. Colonic stenting versus emergency surgery for acute left-sided malignant colonic obstruction: a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:344–52. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan CJ, Dasari BV, Gardiner K. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials of self-expanding metallic stents as a bridge to surgery versus emergency surgery for malignant left-sided large bowel obstruction. Br J Surg. 2012;99:469–76. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dastur JK, Forshaw MJ, Modarai B, Solkar MM, Raymond T, Parker MC. Comparison of short-and long-term outcomes following either insertion of self-expanding metallic stents or emergency surgery in malignant large bowel obstruction. Tech Coloproctol. 2008;12:51–5. doi: 10.1007/s10151-008-0399-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Helyer LK, Law CH, Butler M, Last LD, Smith AJ, Wright FC. Surgery as a bridge to palliative chemotherapy in patients with malignant bowel obstruction from colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:1264–71. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9303-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chi DS, Phaeton R, Miner TJ, Kardos SV, Diaz JP, Leitao MM, Jr, et al. A prospective outcomes analysis of palliative procedures performed for malignant intestinal obstruction due to recurrent ovarian cancer. Oncologist. 2009;14:835–9. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Amikura K, Sakamoto H, Yatsuoka T, Kawashima Y, Nishi-mura Y, Tanaka Y. Surgical management for a malignant bowel obstruction with recurrent gastrointestinal carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2010;101:228–32. doi: 10.1002/jso.21463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dalal KM, Gollub MJ, Miner TJ, Wong WD, Gerdes H, Schattner MA, et al. Management of patients with malignant bowel obstruction and stage IV colorectal cancer. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:822–8. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higashi H, Shida H, Ban K, Yamagata S, Masuda K, Imanari T, et al. Factors affecting successful palliative surgery for malignant bowel obstruction due to peritoneal dissemination from colorectal cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2003;33:357–9. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyg061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wright FC, Chakraborty A, Helyer L, Moravan V, Selby D. Predictors of survival in patients with non-curative stage IV cancer and malignant bowel obstruction. J Surg Oncol. 2010;101:425–9. doi: 10.1002/jso.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]