Abstract

Background

Conditional survival is a measure of the risk of mortality given that a patient has survived a defined period of time. These estimates are clinically helpful, but have not been reported previously for osteosarcoma or Ewing’s sarcoma.

Questions/purposes

We determined the conditional survival of patients with osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma given survival of 1 or more years.

Methods

We used the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program database to investigate cases of osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma in patients younger than 40 years from 1973 to 2009. The SEER Program is managed by the National Cancer Institute and provides survival data gathered from population-based cancer registries. We used an actuarial life table analysis to determine any cancer cause-specific 5-year survival estimates conditional on 1 to 5 years of survival after diagnosis. We performed a similar analysis to determine 20-year survival from the time of diagnosis.

Results

The estimated 5-year survival improved each year after diagnosis. For local/regional osteosarcoma, the 5-year survival improved from 74.8% at baseline to 91.4% at 5 years—meaning that if a patient with localized osteosarcoma lives for 5 years, the chance of living for another 5 years is 91.4%. Similarly, the 5-year survivals for local/regional Ewing’s sarcoma improved from 72.9% at baseline to 92.5% at 5 years, for metastatic osteosarcoma 35.5% at baseline to 85.4% at 5 years, and for metastatic Ewing’s sarcoma 31.7% at baseline to 83.6% at 5 years. The likelihood of 20-year cause-specific survival from the time of diagnosis in osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma was almost 90% or greater after 10 years of survival, suggesting that while most patients will remain disease-free indefinitely, some experience cancer-related complications years after presumed eradication.

Conclusions

The 5-year survival estimates of osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma improve with each additional year of patient survival. Knowledge of a changing risk profile is useful in counseling patients with time. The presence of cause-specific mortality decades after treatment supports lifelong monitoring in this population.

Level of Evidence

Level II, prognostic study. See the Instructions for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

Osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma are the two most common primary sarcomas of bone in children, adolescents, and young adults [9, 22]. Estimates of cancer mortality are commonly presented as the 5-year overall survival from the time of initial diagnosis. While this information is useful for comparing interventions and counseling patients at their initial presentation, it provides little insight into a changing risk profile with time [6, 14].

The concept of conditional survival, a change in the risk of cancer death given survival of a specified time period, is considered a useful tool for patient counseling [4–6, 11, 16, 25, 27, 32]. For instance, Rueth et al. [27] determined that the 10-year survival of patients with high-risk melanoma (30.8%) was substantially worse than that of patients with low-risk melanoma (79.6%) at the time of diagnosis [27]. However, after 8 years of survival the rates equalize, and high-risk patients have the same chance of cancer-related mortality as low-risk patients. Knowledge like this benefits patients and providers by allowing for a more informative discussion regarding the current disease state and prognostic risk assessment [14]. A changing conditional survival also may guide clinical decision making in terms of timing of cancer surveillance and the need for long-term monitoring [4, 11, 27]. To our knowledge, no previous study has attempted to define the conditional survival of osteosarcoma or Ewing’s sarcoma.

Our questions were: (1) Have the baseline 5-year survival rates for patients with osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma improved with time? (2) Does the conditional survival of local/regional osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma improve with each additional year of survival? (3) Does the conditional survival of patients with metastatic osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma improve with each additional year of survival? (4) Is there is a long-term risk of cancer-related mortality after more than 10 years of survival? (5) Can osteosarcoma or Ewing’s sarcoma ever be considered cured?

Patients and Methods

We queried the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program database (National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA) for records of osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma from 1973 to 2009. The SEER program initially started with eight registries in 1973 and has continually added additional participating sites with time. Currently, the database includes 18 geographically diverse areas representing 26% of the US population with efforts to reflect the racial, economic, and social diversity of the country as a whole [23]. The SEER program database is publicly available and does not contain unique patient identifiers (name, birth date, social security number). Therefore, our institutional review board determined that this investigation did not require formal review. We used the SEER*Stat application (Version 8.0.1; National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA) to determine the conditional survival given various conditions.

In the SEER database, patient age is recorded as a categorical variable in 5-year intervals. We limited our investigation to patients 0 to 39 years old at the time of diagnosis to eliminate older individuals who may be treated with different chemotherapeutic protocols. The histologic diagnosis in SEER is coded based on the International Classification of Disease for Oncology, Third Revision [10]. We included all cases of Ewing’s sarcoma and high-grade osteosarcoma. To define the subgroup of high-grade osteosarcoma, we excluded intraosseous well-differentiated osteosarcoma, parosteal osteosarcoma, and periosteal osteosarcoma as these are low- and intermediate- grade tumors known to have a more favorable prognosis compared with the high-grade subtypes. We excluded primary soft tissue osteosarcoma.

We analyzed the survival of metastatic and local/regional disease separately, resulting in four distinct groups (local/regional osteosarcoma, local/regional Ewing’s sarcoma, metastatic osteosarcoma, and metastatic Ewing’s sarcoma). All patients coded as having distant disease were classified as having metastatic disease. Those coded with localized or regional disease were classified as local/regional. Patients coded as unstaged or blank were excluded.

At the time of diagnosis, we identified 2183 cases of local/regional osteosarcoma, 1225 cases of local/regional Ewing’s sarcoma, 487 cases of metastatic osteosarcoma, and 547 cases of metastatic Ewing’s sarcoma at risk and available for analysis. With time, the number of patients at risk and available for analysis steadily decreased (Table 1). The majority of the patients were diagnosed in more recent decades owing to the progressive expansion of the number of contributing locations in the SEER database (Table 2).

Table 1.

Number of subjects at risk at each time in the SEER database, 1973–2009

| Years after diagnosis | Number of subjects | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osteosarcoma (local/regional) | Ewing’s sarcoma (local/regional) | Osteosarcoma (metastatic) | Ewing’s sarcoma (metastatic) | |

| 0 | 2183 | 1225 | 487 | 547 |

| 1 | 1948 | 1098 | 323 | 387 |

| 2 | 1581 | 891 | 205 | 241 |

| 3 | 1361 | 736 | 141 | 165 |

| 4 | 1204 | 613 | 100 | 136 |

| 5 | 1063 | 535 | 82 | 106 |

| 10 | 561 | 280 | 32 | 58 |

| 20 | 244 | 107 | 3 | 22 |

Table 2.

Number of subjects at baseline for each decade in the SEER database, 1973–2009

| Decade | Number of subjects | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osteosarcoma (local/regional) | Ewing’s sarcoma (local/regional) | Osteosarcoma (metastatic) | Ewing’s sarcoma (metastatic) | |

| 1973–79 | 204 | 104 | 25 | 47 |

| 1980–89 | 303 | 194 | 61 | 76 |

| 1990–99 | 475 | 257 | 106 | 109 |

| 2000–09 | 1201 | 670 | 295 | 315 |

Initially, we stratified each group based on decade of diagnosis. We then calculated 5-year survival rates for all patients at risk at the time of diagnosis and contingent on 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 years of survival. Next, we specifically analyzed patients from 1990 to 2009 together, eliminating the patients earlier in the cohort who may not have had access to modern chemotherapy, to give the most accurate view of the current risk profile. Finally, we combined the entire cohort to determine the 20-year survival estimates from the time of diagnosis. Measurements of conditional survival were calculated at 5 and 10 years of survival after diagnosis.

Our survival analysis used an actuarial life table method to determine cause-specific cancer survival, as we were interested in survival in the absence of noncancer mortality. Any mortality attributable to cancer (recurrence, spread, or a subsequent malignancy) qualifies as cause-specific. The SEER registry abstracts information from death certificates in an attempt to specify the attributed cause of death. Specifically, the underlying cause of death is either categorized as cancer or other causes. Individuals with a cause of death other than cancer were censored at the time of death, but included for survival calculations up until time of death. Patients with a missing or unknown cause of death were excluded from all portions of the survival analysis.

Results

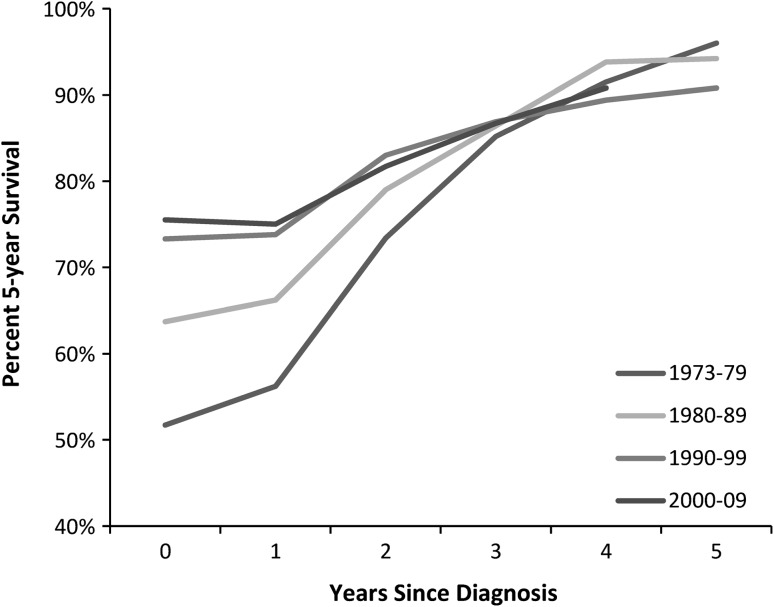

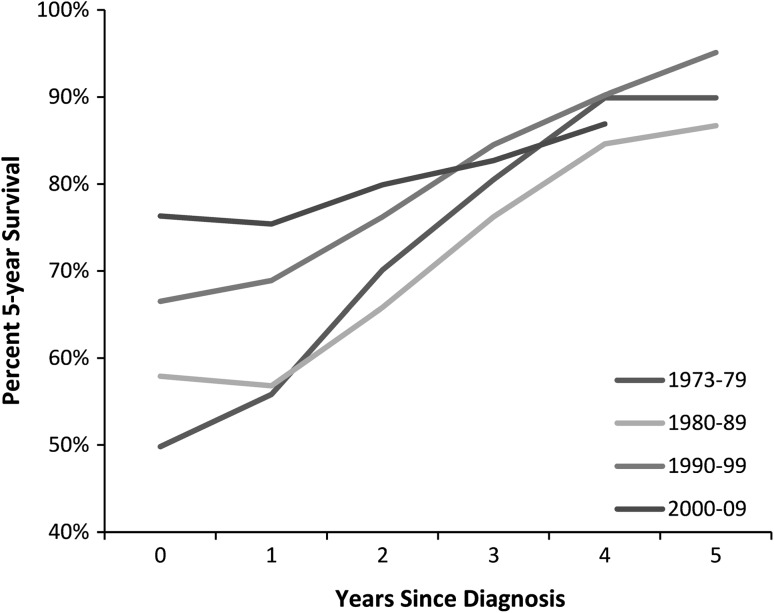

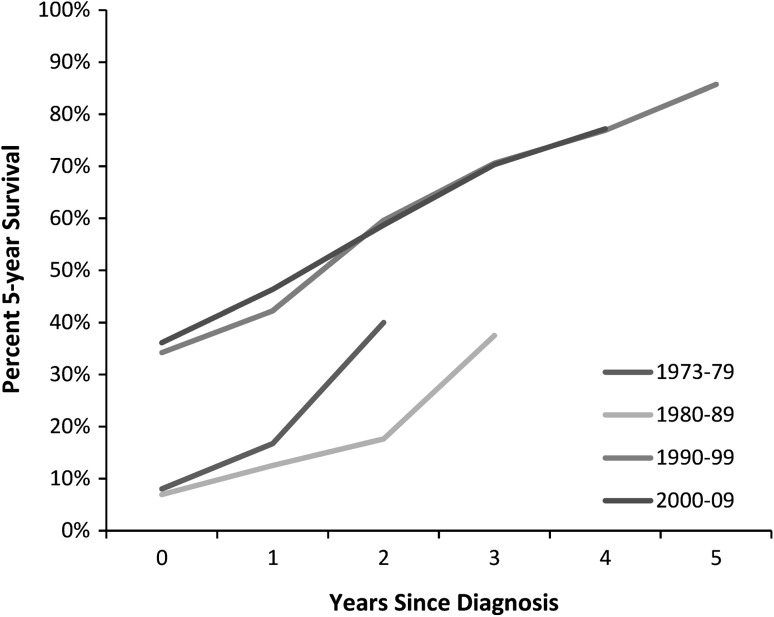

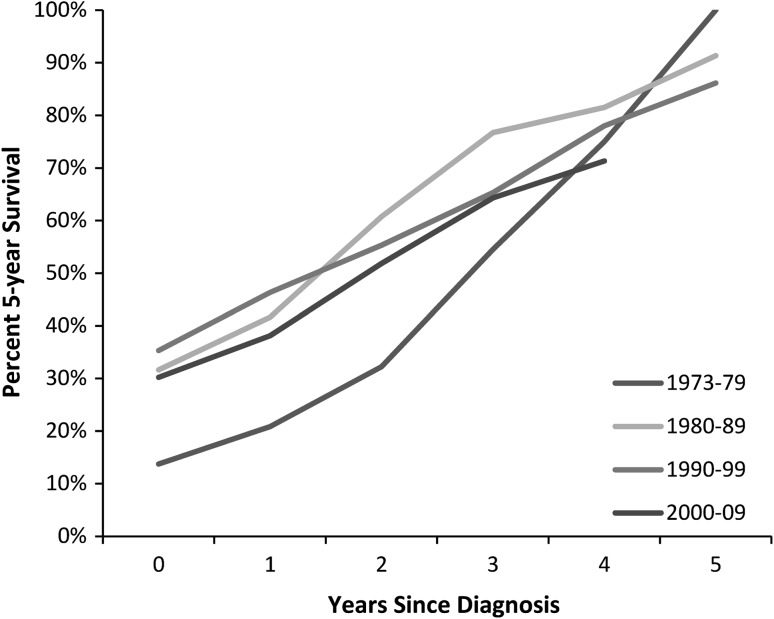

The 5-year survival at baseline improved with time for local/regional disease. For local/regional osteosarcoma, the baseline 5-year survival for 1973 to 1979 was 51.7% (95% CI, 44.6%, 58.4%), compared with 75.5% (95% CI, 72.4%, 78.2%) for 2000 to 2009 (Fig. 1). Similarly, the baseline 5-year survival for local/regional Ewing’s sarcoma was 49.8% (95% CI, 39.9%, 59.0%) for 1973 to 1979, compared with 76.3% (95% CI, 72.2%, 79.9%) for 2000 to 2009 (Fig. 2). The baseline 5-year survival rates for patients with metastatic disease at diagnosis showed a similar trend in improvement with time. Specifically, in metastatic osteosarcoma, the baseline 5-year survival improved from 8.0% (95% CI, 1.4%, 22.5%) for 1973 to 1979 to 36.1% (95% CI, 29.6%, 42.7%) for 2000 to 2009 (Fig. 3). Baseline 5-year survival in metastatic Ewing’s sarcoma increased from 13.7% (95% CI, 5.6%, 25.3%) for 1973 to 1979 to 30.2% (95% CI, 24.2%, 36.4%) for 2000 to 2009 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 1.

A graph shows the cause-specific conditional survival of patients with local/regional osteosarcoma. Each point represents the 5-year survival given the patient has survived 0 to 5 years after diagnosis. Baseline 5-year survival for 1973 to 1979 was 51.7%, compared with75.5% for 2000 to 2009.

Fig. 2.

A graph shows the cause-specific conditional survival of patients with local/regional Ewing’s sarcoma. Each point represents the 5-year survival given the patient has survived 0 to 5 years after diagnosis. Baseline 5-year survival was 49.8% for 1973 to 1979, compared with 76.3% for 2000 to 2009.

Fig. 3.

A graph shows the cause-specific conditional survival of patients with metastatic osteosarcoma. Each point represents the 5-year survival given the patient has survived 0 to 5 years after diagnosis (data points with fewer than five entries are not shown). Baseline 5-year survival was 8.0% for 1973 to 1979, compared with 36.1% for 2000 to 2009.

Fig. 4.

A graph shows the cause-specific conditional survival of patients with metastatic Ewing’s sarcoma. Each point represents the 5-year survival given the patient has survived 0 to 5 years after diagnosis. Baseline 5-year survival was 13.7% for 1973 to 1979, compared with 30.2% for 2000 to 2009.

Combining the observations for 1990 to 2009 showed a favorable increase in 5-year conditional survival estimates given a defined period of survival (Table 3). Interestingly, the 5-year survival rates at baseline and 1 year were essentially equivalent for local/regional disease.

Table 3.

Cause-specific 5-year conditional survival for osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma in the SEER* database, 1990–2009

| Years after diagnosis | 5-year survival (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Osteosarcoma (local/regional) | Ewing’s sarcoma (local/regional) | Osteosarcoma (metastatic) | Ewing’s sarcoma (metastatic) | |

| 0 | 74.8 | 72.9 | 35.5 | 31.7 |

| 1 | 74.8 | 73.4 | 44.5 | 40.6 |

| 2 | 82.1 | 78.8 | 58.3 | 53.1 |

| 3 | 86.6 | 84.1 | 70.4 | 65.8 |

| 4 | 89.7 | 89.0 | 80.5 | 75.3 |

| 5 | 91.4 | 92.5 | 85.4 | 83.6 |

For metastatic disease, the conditional survival improved markedly, with a more vertical slope than local/regional disease, with each additional year of survival.

The cause-specific likelihood of surviving 20 years after diagnosis also increased the longer an individual survived, but a small risk of cause-specific mortality remained (Fig. 5). Given survival for 3 years after diagnosis, the resulting 5-year conditional survival estimates were nearly identical in each decade, with osteosarcoma at 85.2% in the 1970 s and 86.7% in the 2000 s and Ewing’s sarcoma at 80.5% in the 1970 s and 82.7% in the 2000 s. The finding that the effect of decade of diagnosis diminished within the first 5 years (that is, the survival estimate is essentially equivalent regardless of decade of diagnosis given 5 years of survival) supports our decision to combine the entire cohort for a long-term survival analysis.

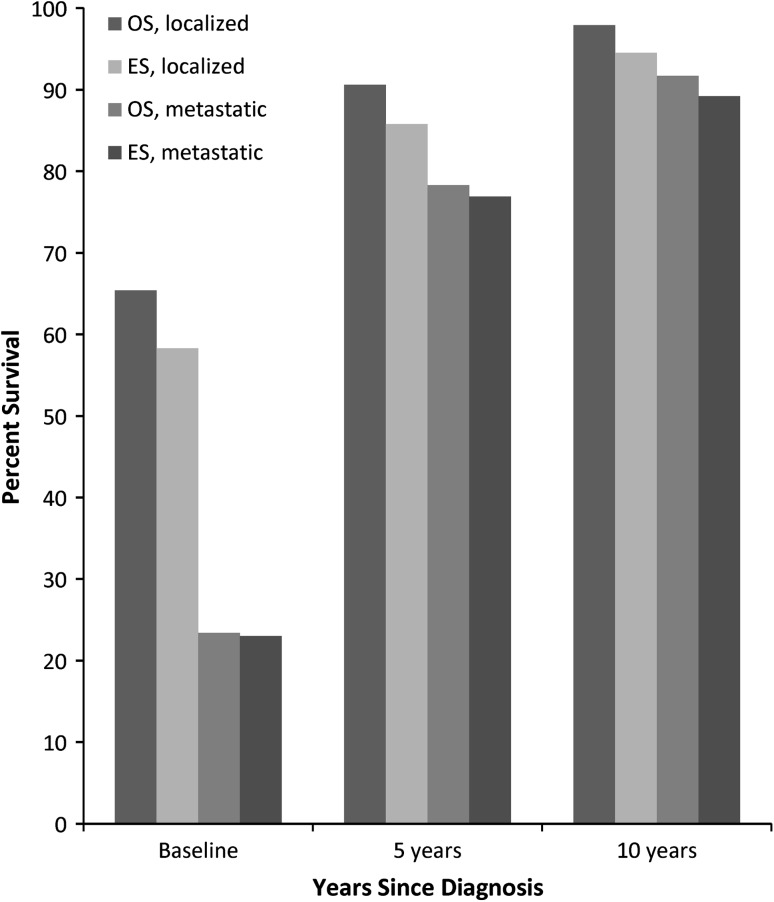

Fig. 5.

A graph shows the 20-year cause-specific survival from the time of diagnosis in patients with osteosarcoma (OS) and Ewing’s sarcoma (ES) at baseline and conditional on 5- and 10–year survival. The 20-year survival after diagnosis, conditional on 10 years of survival, was 97.9% for local/regional osteosarcoma, 94.5% for local/regional Ewing’s sarcoma, 91.7% for metastatic osteosarcoma, and 89.2% for metastatic Ewing’s sarcoma.

The percentage of patients surviving 20 years after diagnosis, conditional on 10 years of survival, was 97.9% for local/regional osteosarcoma, 94.5% for local/regional Ewing’s sarcoma, 91.7% for metastatic osteosarcoma, and 89.2% for metastatic Ewing’s sarcoma. Thus, we did not find that the overall risk of cancer-related mortality completely disappears.

Discussion

Conditional survivorship is a measure of the risk of mortality given that a patient has survived a defined period of time. These estimates are clinically helpful and have not been reported previously for osteosarcoma or Ewing’s sarcoma, although they have for some other common malignancies, including ovarian, brain, squamous cell, breast, pancreatic, lung, melanoma, bladder, gastric, and rectal cancers [5, 6, 11, 15, 17, 20, 21, 27, 29–31]. In an analysis of high-grade osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma in patients younger than 40 years at the time of diagnosis in the SEER database from 1973 to 2009, we found continual improvement in 5-year conditional survival rates with each successive year of survival after diagnosis. In addition, we found that the baseline 5-year survival has improved with time in all cases. For local/regional osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma, the 5-year conditional survival rate given 3 years of survival is essentially the same regardless of the decade of diagnosis. The likelihood of surviving 20 years after diagnosis is near 90% or greater for all groups at 10 years of survival. To our knowledge, this is the first and only study to investigate the conditional survival of osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma.

There are several limitations to our study that require further explanation. First, the use of the SEER database, while providing an ample number of cases to analyze, is not without restrictions. We were not able to confirm the accuracy of the histologic diagnosis or the presence of metastatic disease at diagnosis. Further, we did not have specific information regarding the details of treatment. This does not change the validity of our estimates, but negates the opportunity to stratify individuals by treatment received. We also could not identify patients who presented with pathologic fractures and the survival rates of this cohort may be less than for patients without fractures. Most importantly, we did not have information regarding the development of local recurrence, metastatic spread, or treatment-induced malignancy. Specifically, it was not possible to distinguish disease-free survival or progression-free survival from cause-specific survival. Knowledge of the specific causes of cancer-related mortality (metastasis, recurrence, or secondary malignancies) is unquestionably important and the causes may be avenues for future research.

We elected to include only cases of osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma in patients younger than 40 years as the chemotherapeutic protocols are similar in this cohort. Patients older than this often have medical comorbidities that may preclude an ideal dose of chemotherapy, reflected in a poorer overall survival [7, 12]. Inclusion of the older cohort likely would have made the survival estimates smaller. In addition, we chose not to stratify the survival estimates by the location of the tumor. Axial tumors are known to have a poorer prognosis than extremity tumors [3] and would be an interesting area for further study. Finally, the number of 20-year survivors for metastatic osteosarcoma (n = 3) and Ewing’s sarcoma (n = 22) were small. We included the survival estimates in these entities given the current lack of long-term survival data in the literature, but the generalizability of the findings may be limited owing to the sample size.

We found that, in metastatic and local/regional disease, the baseline 5-year survival rates have improved with time. This observation is consistent with previous investigations [9, 22]. This almost certainly reflects continual improvement in the diagnosis and treatment of osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma (most notably the widespread use and acceptance of chemotherapy in the early 1980 s) [13, 22], although there remains much room for further gains. The conditional survival estimates for each decade converge at approximately 3 years after diagnosis. A possible explanation is that a collection of 3-year survivors reflects a selective cohort with a disproportionate representation of surgically cured disease and outstanding responses to chemotherapeutic modalities.

In general, we found that the conditional survival of patients with local/regional osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma improved with each additional year of survival. It is notable that there was minimal change between the baseline estimate and 1-year conditional survival estimate. This potentially is explained by the first year after diagnosis representing a period of active treatment, and even patients with a poor response to therapy or aggressive biology may have reserves enough to survive 1 year. After the first year, the survival estimate distinctly improves each year.

The trend for metastatic osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma is slightly different, as the interval changes are larger in magnitude than local/regional disease. The implication of this finding is that patients with advanced disease, while having an overall poorer prognosis than local/regional disease, experience a greater positive shift in their risk profile with each passing year. A similar trend in the improvement of 5-year survival rates with each additional year of survival has been noted for breast, colon, ovarian, uterine, melanoma, rectal, bladder, lung, and pancreatic cancer [21].

The analysis of 20-year cause-specific survival from the time of diagnosis suggests a small, but measurable, long-term risk for mortality secondary to tumor recurrence, dissemination, or subsequent malignancy. Although the survival estimates improve with time, there are cancer-related deaths occurring more than 10 years after treatment. This implies that adverse oncologic events can happen well after the initial tumor has been addressed and potentially forgotten. While the SEER data do capture the sequence of primary tumors in patients with more than one primary, they do not distinguish death attributable to dissemination or recurrence of the primary tumor from development of a lethal secondary malignancy. Previous research showed that childhood survivors of osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma have increased subsequent risk of having an additional primary cancer develop [8], and this is likely contributory to the remote cause-specific mortality reflected in our data. Further evidence for late mortality after a pediatric malignancy attributable to recurrence or spread of the primary cancer, subsequent malignancy, or treatment-related complications has been reported [1, 2, 26, 28], and our data support this concern.

We also question the nebulous concept of cancer cure after treatment. Because most of the commonly reported survival estimates are described as 5-year survival, there is a temptation on the part of the patient and provider to assume that the cancer is cured if an individual survives for 5 years after diagnosis. Our investigation clearly showed that this is not the case. The survival rates in our cohort improved with time, but not to the point where cancer cause-specific mortality was negated. Previous studies have recommended lifelong surveillance for patients with osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma to monitor for late dissemination, recurrence, and secondary malignancy [2, 26, 28]. More specifically, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends clinical and radiographic followups for patients with osteosarcoma every 3 months for Years 1 and 2, every 4 months for Year 3, every 6 months for Years 4 and 5, and annually thereafter [24]. Given the positive changes in risk profile with each year of survival in combination with a definable risk of long-term adverse events, our data support these recommendations of gradually extending the time between evaluations yet monitoring patients for life.

A final use of this investigation is as a tool for patient counseling. The 5-year survival estimates change with time, and clinicians may use these data to explain to patients the continual improvement in their prognosis, tempered with the definite need for continued monitoring. Previous investigations have shown that disclosing solid data, such as a numerical prognosis, is preferred by patients and often will instill hope, even when the prognosis is dismal [18, 19]. Because revision of the baseline 5-year survival results in a more optimistic and encouraging prognostic estimate in osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma, the use of the most applicable conditional survival estimates are likely to be appreciated and welcomed by patients and their families.

We found that the conditional survival of patients with osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma changes favorably as individuals survive past their initial treatments. Patients make substantial improvements in prognosis nearly every year but continue to be at risk for mortality related to cancer even after more than 10 years of survival. Our findings support the need for lifelong surveillance of these patients and supply a clinical tool that may be helpful in counseling short- and long-term survivors of childhood osteosarcoma and Ewing’s sarcoma.

Footnotes

One of the authors (BJM) certifies that he has received, during the study period, funding from the NIH (T32 Training Grant CA148062-01).

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved or waived approval for the human protocol for this investigation and that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research.

References

- 1.Armstrong GT, Liu Q, Yasui Y, Neglia JP, Leisenring W, Robison LL, Mertens AC. Late mortality among 5-year survivors of childhood cancer: a summary from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2328–2338. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bacci G, Forni C, Longhi A, Ferrari S, Donati D, De Paolis M, Barbieri E, Pignotti E, Rosito P, Versari M. Long-term outcome for patients with non-metastatic Ewing’s sarcoma treated with adjuvant and neoadjuvant chemotherapies: 402 patients treated at Rizzoli between 1972 and 1992. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:73–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2003.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bielack SS, Kempf-Bielack B, Delling G, Exner GU, Flege S, Helmke K, Kotz R, Salzer-Kuntschik M, Werner M, Winkelmann W, Zoubek A, Jurgens H, Winkler K. Prognostic factors in high-grade osteosarcoma of the extremities or trunk: an analysis of 1,702 patients treated on neoadjuvant cooperative osteosarcoma study group protocols. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:776–790. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.3.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bleyer A, Choi M, Fuller CD, Thomas CR, Jr, Wang SJ. Relative lack of conditional survival improvement in young adults with cancer. Semin Oncol. 2009;36:460–467. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi M, Fuller CD, Thomas CR, Jr, Wang SJ. Conditional survival in ovarian cancer: results from the SEER dataset 1988–2001. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;109:203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis FG, McCarthy BJ, Freels S, Kupelian V, Bondy ML. The conditional probability of survival of patients with primary malignant brain tumors: surveillance, epidemiology, and end results (SEER) data. Cancer. 1999;85:485–491. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19990115)85:2<485::AID-CNCR29>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ek ET, Ojaimi J, Kitagawa Y, Choong PF. Outcome of patients with osteosarcoma over 40 years of age: is angiogenesis a marker of survival? Int Semin Surg Oncol. 2006;3:7. doi: 10.1186/1477-7800-3-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engels EA, Fraumeni JF Jr. New Malignancies Following Cancer of the Bone and Soft Tissue, and Kaposi Sarcoma. In: Curtis RE, Freedman DM, Ron E, Ries LAG, Hacker DG, Edwards BK, Tucker MA, Fraumeni JF Jr, eds. New Malignancies Among Cancer Survivors: SEER Cancer Registries, 1973–2000. NIH Publ. No. 05-5302. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2006:313–337.

- 9.Esiashvili N, Goodman M, Marcus RB., Jr Changes in incidence and survival of Ewing sarcoma patients over the past 3 decades: Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results data. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2008;30:425–430. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e31816e22f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fritz A, Jack A, Shanmugaratnam K, Sobin L, Parkin DM, Whelan S, editors. International Classification of Diseases for Oncology. 3. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuller CD, Wang SJ, Thomas CR, Jr, Hoffman HT, Weber RS, Rosenthal DI. Conditional survival in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: results from the SEER dataset 1973–1998. Cancer. 2007;109:1331–1343. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grimer RJ, Cannon SR, Taminiau AM, Bielack S, Kempf-Bielack B, Windhager R, Dominkus M, Saeter G, Bauer H, Meller I, Szendroi M, Folleras G, San-Julian M, van der Eijken J. Osteosarcoma over the age of forty. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:157–163. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(02)00478-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Handelsman H, Carter SK. Current therapies in osteosarcoma. Cancer Treat Rev. 1975;2:77–83. doi: 10.1016/S0305-7372(75)80017-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henson DE, Ries LA. On the estimation of survival. Semin Surg Oncol. 1994;10:2–6. doi: 10.1002/ssu.2980100103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henson DE, Ries LA, Carriaga MT. Conditional survival of 56,268 patients with breast cancer. Cancer. 1995;76:237–242. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19950715)76:2<237::AID-CNCR2820760213>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson DR, Ma DJ, Buckner JC, Hammack JE. Conditional probability of long-term survival in glioblastoma: a population-based analysis. Cancer. 2012;118:5608–5613. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Katz MH, Hu CY, Fleming JB, Pisters PW, Lee JE, Chang GJ. Clinical calculator of conditional survival estimates for resected and unresected survivors of pancreatic cancer. Arch Surg. 2012;147:513–519. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.2281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mack JW, Wolfe J, Cook EF, Grier HE, Cleary PD, Weeks JC. Hope and prognostic disclosure. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5636–5642. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.6110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mack JW, Wolfe J, Grier HE, Cleary PD, Weeks JC. Communication about prognosis between parents and physicians of children with cancer: parent preferences and the impact of prognostic information. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5265–5270. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merrill RM, Henson DE, Barnes M. Conditional survival among patients with carcinoma of the lung. Chest. 1999;116:697–703. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.3.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Merrill RM, Hunter BD. Conditional survival among cancer patients in the United States. Oncologist. 2010;15:873–882. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mirabello L, Troisi RJ, Savage SA. Osteosarcoma incidence and survival rates from 1973 to 2004: data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer. 2009;115:1531–1543. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Cancer Institute. National Cancer Institute Fact Sheet.Available at: http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/factsheet/disparities/cancer-health-disparities. Accessed June 3, 2013.

- 24.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Available at: http:www.nccn.org/index.asp. Accessed December 28, 2012.

- 25.Parsons HM, Habermann EB, Tuttle TM, Al-Refaie WB. Conditional survival of extremity soft-tissue sarcoma: results beyond the staging system. Cancer. 2011;117:1055–1060. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reulen RC, Winter DL, Frobisher C, Lancashire ER, Stiller CA, Jenney ME, Skinner R, Stevens MC, Hawkins MM, British Childhood Cancer Survivor Study Steering Group Long-term cause-specific mortality among survivors of childhood cancer. JAMA. 2010;304:172–179. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rueth NM, Groth SS, Tuttle TM, Virnig BA, Al-Refaie WB, Habermann EB. Conditional survival after surgical treatment of melanoma: an analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1662–1668. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0965-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skinner R, Wallace WH, Levitt GA, UK Children’s Cancer Study Group Late Effects Group Long-term follow-up of people who have survived cancer during childhood. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:489–498. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70724-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun M, Abdollah F, Bianchi M, Trinh QD, Shariat SF, Jeldres C, Tian Z, Hansen J, Briganti A, Graefen M, Montorsi F, Perrotte P, Karakiewicz PI. Conditional survival of patients with urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder treated with radical cystectomy. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48:1503–1511. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2011.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang SJ, Emery R, Fuller CD, Kim JS, Sittig DF, Thomas CR. Conditional survival in gastric cancer: a SEER database analysis. Gastric Cancer. 2007;10:153–158. doi: 10.1007/s10120-007-0424-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang SJ, Fuller CD, Emery R, Thomas CR. Conditional survival in rectal cancer: a SEER database analysis. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2007;1:84–89. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xing Y, Chang GJ, Hu CY, Askew RL, Ross MI, Gershenwald JE, Lee JE, Mansfield PF, Lucci A, Cormier JN. Conditional survival estimates improve over time for patients with advanced melanoma: results from a population-based analysis. Cancer. 2010;116:2234–2241. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]