Abstract

Background

Some orthopaedic procedures, including TKA, enjoy high survivorship but leave many patients dissatisfied because of residual pain and functional limitations. An important cause of patient dissatisfaction is unfulfilled preoperative expectations. This arises, in part, from differences between provider and patient in their definition of a successful outcome.

Where Are We Now?

Patients generally are less satisfied with their outcomes than surgeons. While patients are initially concerned with symptom relief, their long-term expectations include return of symptom-free function, especially in terms of activities that are personally important. While surgeons share their patients’ desire to achieve their goals, they are aware this will not always occur. Conversely, patients do not always realize some of their expectations cannot be met by current orthopaedic procedures, and this gap in understanding is an important source of discrepancies in expectations and patient dissatisfaction.

Where Do We Need to Go?

An essential prerequisite for mutual understanding is information that is accurate, objective, and relevant to the patient’s condition and lifestyle. This critical information must also be understandable within the educational and cultural background of each patient to enable informed participation in a shared decision making process. Once this is achieved, it will become easier to formulate similar expectations regarding the likely level of function and symptom relief and the risk of adverse events, including persistent pain, complications, and revision surgery.

How Do We Get There?

Predictive models of patient outcomes, based on objective data, are needed to inform decision making on the individual level. This can be achieved once comprehensive data become available capturing the lifestyles of patients of diverse ages and backgrounds, including data documenting the frequency and intensity of participation in sporting and recreational activities. There is also a need for greater attention to the process of informing patients of the outcome of orthopaedic procedures, not simply for gaining more meaningful consent, but so that patients and providers may achieve greater alignment of expectations and increased acceptance of both the benefits and limitations of alternative treatments.

Introduction

Alignment of the goals of the surgeon and the patient before an orthopaedic procedure makes it more likely the patient will be satisfied with surgery [14, 38]. In addition, for patients’ consent to be truly informed, there must be a meaningful appreciation of the likely impact of a treatment in terms of symptoms, function, and residual deficits, as well as of the likelihood of an adverse outcome [72, 74]. The question of perspective also forms the basis of patient-reported outcome measures. Historically, assessments of outcome after orthopedic procedures have been derived from the surgeon’s input and expectations [37]. However, over the last three decades, there has been a shift to the perceptions of patients in the evaluation of outcomes of orthopaedic procedures [5]. This change has been fueled by the growing realization that patients, not surgeons, define whether an orthopaedic procedure is successful and whether to seek additional treatment, including revision [6, 9–11, 25].

Nonetheless, the surgeon has a professional and legal responsibility to justify his or her actions in recommending a course of treatment to the patient and in adequately informing each patient of the expected result and possible complications associated with that treatment. This process can only work effectively if patient and provider share an understanding of what defines “success” and if they agree on the relative values, both positive and negative, of deviations from the ideal result [1, 14, 38, 74].

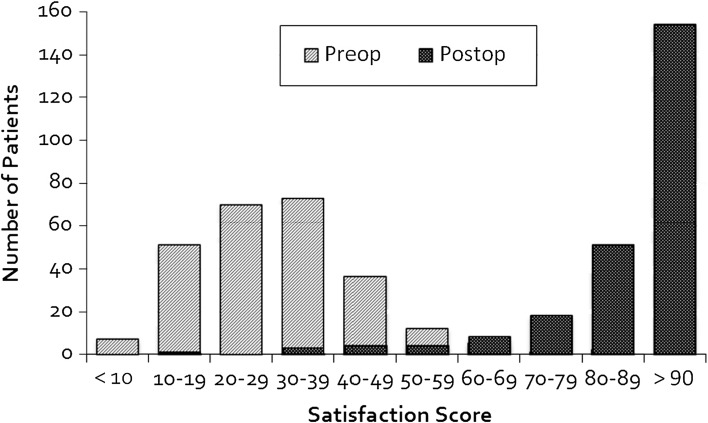

Unfortunately, the definition of success has proved elusive, and the literature offers little specific guidance, in particular from the patient’s point of view. Numerous studies have previously reported the incidence of satisfaction of patients after THAs and TKAs, with values ranging from 77% to 95%, depending on the procedure, the geographic location of the study, and the way in which the questions were asked (Fig. 1) [2, 4, 27, 28, 42, 54, 68]. Large variations have also been noted in terms of the ability of joint arthroplasty to restore patients to the functional status they experienced before the onset of joint disease [43, 44, 49, 54]. This is due, in large part, to differences in the lifestyle and expectations of each individual, as well as the willingness of patients to tolerate residual knee symptoms.

Fig. 1.

This histogram of data derived from the validation trials of the New Knee Society Score depicts the distribution of satisfaction scores at a minimum of 1 year post-TKA (maximum score = 100 points). The range of scores is approximately the same postoperatively as preoperatively, with an average improvement of more than 60 points. Preop = preoperative; postop = postoperative.

Many patients expect joint arthroplasty not only to relieve symptoms but also to restore the ability to perform sporting and recreational activities without pain, stiffness, or swelling [13, 19]. This discrepancy tends to be greater in patients younger than 55 years [25, 52, 65, 74]. Some of these individuals, in fact, developed arthritis as a direct result of injuries incurred in sporting or fitness activities. For this patient group and for an increasing proportion of older patients with joint arthroplasty, the restoration of normal joint function involves returning to a predisease regimen of activities. Despite the desire to participate in recreation and exercise, biomechanical studies using instrumented prostheses of the hip and knee confirm that these physically demanding activities greatly elevate the loads and torques acting on the implanted components [15, 33, 60, 67]. This has led to the formulation of advice to patients from surgical societies concerning activities that are recommended and strongly discouraged after joint arthroplasty [12, 23, 48, 65].

Given the inherent difference in the perspectives of surgeons and patients, combined with variations between individuals in terms of how short-term risk and long-term reward are processed, we performed a review of the available evidence comparing the expectations of patients and surgeons with regard to the outcome of orthopaedic procedures, using hip and knee arthroplasty as the focus of our inquiry, with particular attention to the presence or absence of data supporting these expectations of outcome.

Where Are We Now?

Patients’ expectations after operative procedure are based on preoperative judgment of potential benefits and hopes for achieving the desired goals [24, 31, 61]. Numerous studies have documented that the immediate priority of patients undergoing joint arthroplasty is relief of pain, stiffness, and swelling. Almost all patients expect to perform the activities of daily life (ADLs) without limitation after surgery [19, 29, 39, 41, 45, 50, 53] and that their ability to perform these activities will improve postoperatively [29, 41, 53]. In these studies, the majority of patients also assumed that they would have vast improvements in their ability to complete activities requiring a high range of joint mobility, such as putting on shoes and socks (94%) and clipping toenails (88% and 93% in two studies looking at this end point) [29, 41]. Interestingly, fewer patients expected improvement in sexual ability after surgery (33% and 65% in two studies evaluating this end point) [29, 41].

Patients appear to distinguish little between improvements in ADLs after surgery and improvements in exercise/sports activities (72%–95%) and recreational activities (88%–93%). The only individual sports specifically addressed in published studies have been golfing and dancing, which 41% of patients with TKA expected they would be capable of performing after recovery [53]. However, over a period of up to 5 years after TKA, only 24% of these patients actually experienced an improvement in their sporting or recreational abilities. By contrast, the vast majority of patients with hip arthroplasty reported an improved ability to participate in recreational or social activities at 4 years after surgery [41].

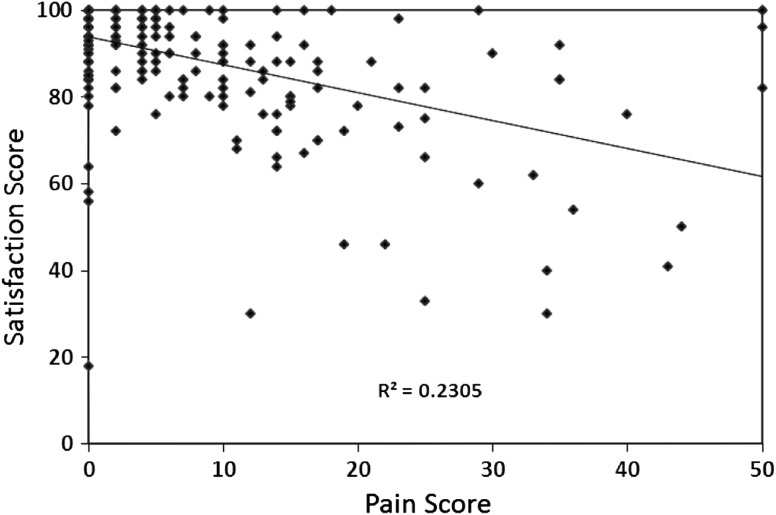

Failure to meet presurgical expectations of activity level after full recovery has been identified as a factor influencing patient satisfaction with surgery (p < 0.001 [54]) [8, 39]. Patients’ dissatisfaction stems from residual pain, swelling, and/or joint stiffness (Fig. 2) [11, 54] and/or failure of the clinical result to match the patient’s preoperative expectations [8, 35, 41, 46, 54, 55, 62]. In addition, a recent study demonstrated a connection between these two factors, as patient dissatisfaction after TKA was found to be most prevalent in patients who experienced knee symptoms when performing activities that they considered personally important [55].

Fig. 2.

Data derived from the validation trials of the New Knee Society Score show the correlation between values of the New Knee Society satisfaction score and pain score (sum of pain with walking and pain on stairs and inclines). All patients were enrolled at a minimum of 1 year post-TKA. Increasing levels of knee pain with activity are reflected in a larger value of the pain score.

A major limitation of the orthopaedic literature is that few studies have reported the expectations and satisfaction of surgeons regarding the outcome of joint arthroplasty. Historically, the clinical results reported by surgeons have been assumed to be accurate and reproducible, despite accounts demonstrating otherwise [22, 41, 47, 50]. The few articles exploring this topic support the conclusion that surgeons’ expectations of patients’ outcomes vary with the surgeons’ operative volume and years of experience, the patient’s overall medical condition, and the complexity of the procedure [71]. In a study by Wright et al. [71], surgeons who performed larger numbers of knee arthroplasty procedures estimated that higher proportions of patients would have a reduction in pain, improvement in walking ability, and improved quality of life after this operation. The high-volume surgeons also judged, on average, that the incidence of complications would be lower than surgeons who performed fewer procedures.

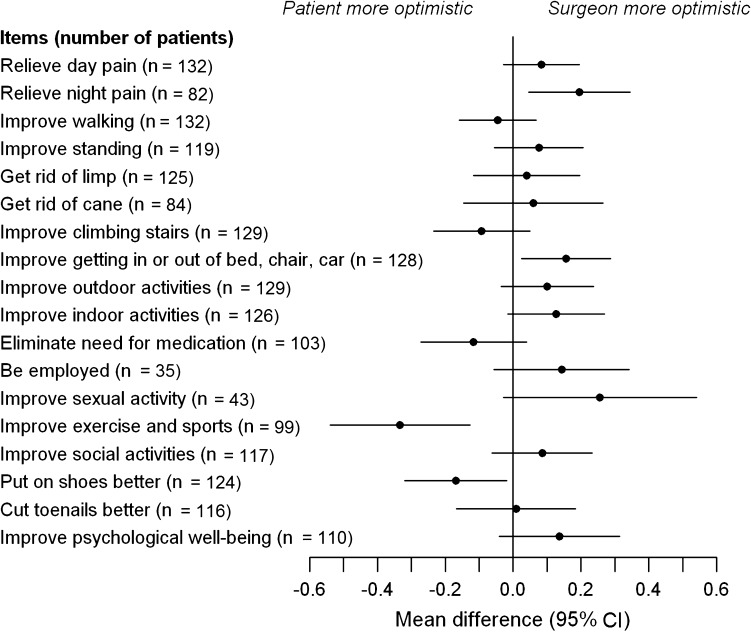

In other studies, surgeons and their patients differed in their assessments of the patient’s current condition and in their predictions of the outcome of an operative procedure, with the surgeons’ expectations tending to be more optimistic (Fig. 3) [13, 31, 37, 50]. In a cross-sectional study of 100 surgeons and 370 patients undergoing THA or TKA, Moran et al. [50] found that the surgeons expected better results and predicted higher postoperative functional scores than the patients. Patients and physicians also display different priorities in evaluating treatments for osteoarthritis, with patients giving priority to elimination of symptoms and resumption of physical activities and physicians prioritizing the absence of long-term adverse events [13, 31]. In a study of 147 THAs, Lieberman et al. [37] reported a marked disparity in the evaluations of patients and physicians, with patients placing greater weight on the presence of residual symptoms in assessing the outcome of their procedure. Differences between patients and their surgeons were greatest in cases where the patient reported significant hip pain at followup and overall dissatisfaction with the outcome.

Fig. 3.

Results of a preoperative survey of 132 patients and 16 joint surgeons concerning expected outcomes after THA are shown. Differences in the average responses of surgeons and patients are plotted for each item, with corresponding 95% CIs. Reprinted from Jourdan C, Poiraudeau S, Descamps S, Nizard R, Hamadouche M, Anract P, Boisgard S, Galvin M, Ravaud P. Comparison of patient and surgeon expectations of total hip arthroplasty. Plos One. 2012;7:e30195–e30195.

Age and preoperative functional status have been identified as potential causes for the discrepancy between patient and surgeon expectations [51, 73]. Patients with lower preoperative functional status express higher expectations from total joint arthroplasty than the operating surgeon [18, 41]. In addition, the discrepancy between patients and surgeons was shown to be greater in patients who had less successful outcomes [11, 47]. In a comparative analysis of patients’ and surgeons’ response to the same clinical questionnaire in 1273 THAs, McGee et al. [47] showed that a larger discrepancy between the reports existed in patients with comorbidities or substantial residual symptoms post-recovery. This may be due to unrealistic expectations (especially with physical activity after joint arthroplasty), persistent pain in the operative limb, or comorbidities, including pain and stiffness in other joints. Several studies have also reported concordance between patients’ and physicians’ evaluations in patients reporting little or no pain at the time of evaluation [37, 47, 53, 63]. Also, patients who were 45 years or younger had greater agreement with their surgeon in their assessment of expectation and outcomes [47]. However, when patients are dissatisfied with their outcome, the patient/surgeon discrepancy is often greatest [11, 47].

The discrepancy between patients’ and surgeons’ assessment of the outcome of orthopaedic treatments arises from a host of factors, including the inherent variability of many procedures and differences in the expectations of patients and surgeons regarding the likely outcome. Surgeons and patients may also differ in their assessment of the significance of different degrees of residual symptoms and the importance of full recovery of function. Surgeons may also fail to adequately communicate the limitations of proposed procedures in terms that the patients can understand. Within the academic literature, there has been increased attention to each of these factors in an attempt to improve the process of providing the right amount and kind of information to facilitate informed consent of patients before treatment. The goal of informed consent is to develop within each patient an understanding of the risks and complications of a course of treatment so that they are able to make informed decisions about their care. However, the method used to educate the patient and obtain consent may have an adverse effect on the accuracy of recall of the information provided [34, 70]. Langdon et al. [34] observed that patients who received written information before admission for THA scored significantly higher on recall questionnaires than the patients who received verbal information.

In addition, poor recollection of information provided by the medical staff can lead patients to poorly judge the outcome of their surgery and the quality of their interactions with their surgeon [59]. Robinson and Merav [59] tested patients for recall at 4 to 6 months postoperatively and identified poor retention in all categories of information provided during informed consent, with the poorest score being achieved in the single category of potential complications. Of the 20 patients tested, 16 expressed no doubts regarding their recollections and denied that major items were discussed at all. In an effort to align patient and provider expectations, it is wise to document consent as part of the clinical record, because the patients’ memory of the event has been proven untrustworthy [26, 34, 59]. The staff responsible for obtaining consent from the patient can also contribute to skewed patient and provider expectations. The most common cause of medical litigation is inadequate doctor-patient communication, often resulting from inaccurate or misleading information provided by junior staff [57, 58]. A study by Soin et al. [64] identified a large discrepancy between the responses of senior and junior members of a surgical team when asked to estimate the mortality rates of elective procedures. It may be inferred that, if senior surgeons were to inform patients of the relevant risks of these procedures, there would be greater alignment of expectations regarding outcome and improved patient satisfaction.

Mancuso et al. [40] showed that patient expectations before total joint arthroplasty influence the postoperative outcomes. Other reports have demonstrated varying expectations among surgeons themselves. In a survey of 357 total joint surgeons, Dy et al. [17] showed significant disagreement between surgeons in predicting the outcome of total joint arthroplasty in patients with higher demands and personal expectations. This lack of uniform opinion mirrors the views expressed in published studies and may be partly due to variations in indications, timing, type of approach, implant and fixation used, postoperative recovery, ethnic and racial factors, and uncertainty concerning the durability of modern implants and materials [7, 17, 20, 36, 39]. Nonetheless, agreement of the surgeon and patient regarding clear and realistic outcomes of orthopaedic procedures is essential to prevent discrepancies in expectations, avoid disappointment, and improve satisfaction.

Where Do We Need to Go?

The recent focus on joint registries and the documentation of revision rates from joint arthroplasties has brought increased awareness to the differences in the ultimate success of these operations due to variations in patients, surgeons, and implants. One of the great strengths of joint registries is the sheer volume of data available for analysis and the relative frequency and similarity of the procedures under study. In fields other than joint arthroplasty and in the treatment of more complex and unusual conditions than osteoarthritis of the hip or knee, smaller case numbers and greater diversity make analysis of outcome and predictions less reliable, especially on a case-by-case basis. In addition, even in common procedures such as hip and knee arthroplasty, much more attention has been paid to the survivorship of the prosthesis than the quality of the outcome experienced by the patient. The data that have been collected reveal that there are large differences between failure rates of procedures and the outcome in terms of patient satisfaction, relief of symptoms, and restoration of abilities significant to the patient [3, 52–55, 69].

Before patients and surgeons can compare their expectations of orthopaedic treatments and procedures, there must be a common factual basis for assessment of the expected results. This includes the likelihood of achieving a specific level of outcome and the risk of adverse events, including loss of function and the possibility of revision surgery. An essential prerequisite for shared decision making is shared information that both surgeon and patient believe is accurate, objective, and relevant to the patient’s condition and lifestyle. As this information does not exist at present, it is not possible to make accurate prognostic predictions that are meaningful to each patient. However, if data were available to form the basis for predictive models, it would be possible to quantify risk factors on the basis of factors presented by the patient (eg, age, sex, BMI, type of prosthesis, etc). This information could then lead to improved outcomes through improvements in decision making and the surgical procedures themselves and in changes in variables under the patient’s control (eg, high-demand activities, participation in physical therapy, moderation of weight, consumption of alcohol, etc).

For shared decision making to be authentic, patients must be committed to developing an informed understanding of the likely outcome and possible complications of alternative treatments. This requires effort in listening to the surgeon and associated staff and in contemplating different scenarios that may arise should the outcome of a procedure be as successful as, or less successful than expected. Most importantly, patients must accept responsibility for their own health and be prepared to play an active role in selecting a course of treatment. This also means being prepared to accept the outcome of that decision, which both surgeon and patient must recognize is not always assured. On the other side of the partnership, surgeons must be willing to explore the goals and aspirations of each individual patient, and discuss the likelihood that these will be achieved. This dialogue must be undertaken using language and terminology appropriate to each patient, given their level of education, native language, and cultural background. Surgeons must also appreciate that because of their commitment to surgical treatment of many orthopaedic conditions, they may unconsciously fail to adequately convey the known limitations of a surgical procedure.

How Do We Get There?

The goal of informed decision making is to provide patients and providers with specific information relating to the expected outcome of an orthopaedic procedure, in terms of the quality of outcome. For this to be achieved, each dimension of outcome (ie, function, relief of symptoms, patient satisfaction) must be measured using validated instruments. These may be in the form of psychometric measurements (eg, patient-generated questionnaires), objective measurements of physical function (ie, joint kinematics or kinematics), or radiographic measurements of skeletal health or stability. Once these outcome data are available, predictive models may be developed, provided that a set of relevant descriptors can be collected and correlated with each of the major outcome variable. For example, to provide a 55-year-old male patient with a prediction of his likely outcome if he resumes downhill skiing or playing tennis, significant factors would probably include the outcome variables predicted (eg, implant failure, recurrent symptoms that resolve with rest), the patient’s BMI, intensity of activity, comorbid conditions, and previous history of injuries. Given the diversity of activities that patients regard as personally important and the array of variables that may affect outcome, a very large data set would be required to make predictions sufficiently specific to be meaningful at the individual level. An additional complication is that some outcomes, such as implant failure, will not be common enough to allow accurate risk assessment until an extended postoperative period, typically more than 10 years. This means that some parameters defining outcome (eg, long-term survivorship) cannot be addressed prospectively in the short term. Nonetheless, data collected as part of the ongoing efforts to expand joint registries may serve as a suitable source of data relating to the risk of revision in the years ahead.

We have also identified the necessity for surgeons and patients to reach an understanding of the true risks and consequences of different lifestyles on the outcome of joint arthroplasty. This will only be achieved once we have comprehensive data documenting the sporting and recreational activities of patients, both in terms of the activities performed and the frequency and intensity of participation, in addition to the outcome experienced by each patient. Although young and active patients will often assume that surgeons are inherently conservative as part of the medical establishment and therefore will give advice that restricts active pursuits, there is published evidence that demanding activities are detrimental to the longevity of joint arthroplasties [21, 30, 56, 60]. In one retrospective study, practicing a high-impact sport was a risk factor for failure of a joint replacement procedure, with an odds ratio of 3.64 (95% CI, 1.49–8.9) [56]. Patients in the high-impact sport group also had more mechanical failures (p = 0.001) than those who did not participate in high-impact sports. At 15 years’ followup, Kaplan-Meier analysis yielded an 80% survivorship for the high-impact sport group versus 93.5% in the low-activity group. Whether the same penalty will be seen with improved bearing materials is presently unknown.

We have also noted that the documented differences in surgeons’ and patients’ assessment of the outcome of orthopaedic procedures arise to a large degree because of differences in priorities. For this situation to change, surgical training will need to place greater emphasis on patient expectations and satisfaction. In assessing their success in treating a patient, trainees must be taught to respect the inherent right of patients to assert their own values and priorities and to recognize that few outcomes will be satisfactory if the outcomes do not meet the needs of the patient.

Discussion

The orthopaedic literature lacks a substantive analysis of factors contributing to the belief of some patients that their postoperative outcome fails to meet their preoperative expectations.

Although both providers and patients share a common desire for restoration of musculoskeletal function after injury or degeneration, the outcome of many orthopaedic procedures remains variable. As hope and aspiration are essential components of surgical recovery, many patients have overly sanguine expectations and may not choose to give their full attention to all the possible outcomes of their procedure. In reality, providers care about the same things patients do; however, a perfect result is never assured, and the definition of success varies from one individual to the next.

Studies show that patient and surgeon expectations after joint arthroplasty vary greatly [19, 29]. While similar expectations were observed for improvement in ADL function, the greatest disparities occurred in items assessing improved ability to perform sporting and high-ROM activities [12, 16, 48, 66]. As many patients report significantly higher expectations than their surgeons when considering the likelihood of actually returning to higher-level activities, improved communication between surgeons and patients appears critical to align the goals aspirations of both parties with realistic goals in terms of functional outcomes [32, 74]. Unless this level of consensus can be achieved as part of the preoperative decision making process, it is likely that the prevalence of patient dissatisfaction with the outcome of joint arthroplasty will continue to increase as patients become younger and more demanding of these procedures.

As the practice of modern medicine becomes increasingly personalized, outcomes tools that consider individual risk factors will become more important. Conversely, patients will discount advice that is not evidence-based and is derived from generalized conclusions that ignore age, sex, experience, activity preferences, and lifestyle. Clearly work and investment are required to harness the promise of modern outcome instruments to facilitate shared decision making as a key component of musculoskeletal medicine in the decades to come.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Ken Mathis, Dr Walter Lowe, Dr Melvyn Harrington, Dr Richard Kearns, Dr Greg Stocks, Dr Vas Mathews, Dr. Brian Parsley, Prof Justin Cobb, Dr. Aaron Rosenberg, Prof Alister Hart, Dr Sarah Muirhead-Allwood, Dr Michael Heggeness, Dr Jesse Dickson, Dr Andrew Shimmin, Dr Ormonde Mahoney, Dr Pat McCullough, Dr Jan Victor, Dr David Lintner, Dr Aaron Rosenberg, Dr Tony Hedley, Dr Richard Field, Dr Glenn Landon, Dr Steve Incavo, Dr Mark Brinker, Dr Roger Levy, Dr Jim Benjamin, Dr Gil Scuderi, Dr Jim Pritchard, Dr Sam Tarabichi, Dr Kim Bertin, Dr Ashok Rajgopal, and Dr Richard Moore for their valuable and insightful discussions on the topic of patient and surgeon expectations.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she, or a member of his or her immediate family, has no commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

This work was performed at the Institute of Orthopedic Research and Education, Houston, TX, USA.

Contributor Information

Philip C. Noble, Email: pnoble@bcm.edu.

Sophie Fuller-Lafreniere, Email: slfuller-lafreniere@tmhs.org.

Morteza Meftah, Email: mmeftah@tmhs.org.

Maureen K. Dwyer, Email: mkdwyer@partners.org.

References

- 1.Adams JR, Drake RE. Shared decision-making and evidence-based practice. Commun Ment Health J. 2006;42:87–105. doi: 10.1007/s10597-005-9005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson JG, Wixson RL, Tsai D, Stulberg SD, Chang RW. Functional outcome and patient satisfaction in total knee patients over the age of 75. J Arthroplasty. 1996;11:831–840. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(96)80183-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Australian Orthopaedic Association. National Joint Replacement Registry Annual Report 2010. Available at: http://www.dmac.Adelaide.edu.au/aoanjrr/documents/AnnualReports2011/AnnualReport_2011_WebVersion.pdf. 2011;1–201. Accessed February 14, 2013.

- 4.Barrack RL, Engh G, Rorabeck C, Sawhney J, Woolfrey M. Patient satisfaction and outcome after septic versus aseptic revision total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2000;15:990–993. doi: 10.1054/arth.2000.16504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bayley KB, London MR, Grunkemeier GL, Lansky DJ. Measuring the success of treatment in patient terms. Med Care. 1995;33(4 suppl):AS226–AS235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blalock SJ, Orlando M, Mutran EJ, DeVellis RF, DeVellis BM. Effect of satisfaction with one’s abilities on positive and negative affect among individuals with recently diagnosed rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 1998;11:158–165. doi: 10.1002/art.1790110303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borkhoff CM, Hawker GA, Wright JG. Patient gender affects the referral and recommendation for total joint arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:1829–1837. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1879-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bourne RB, Chesworth BM, Davis AM, Mahomed NN, Charron KD. Patient satisfaction after total knee arthroplasty: who is satisfied and who is not? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:57–63. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1119-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brinker MR, Savory CG, Weeden SH, Aucoin HC, Curd DT. The results of total knee arthroplasty in Workers’ Compensation patients. Bull Hosp Jt Dis. 1998;57:80–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brokelman RB, Meijerink HJ, de Boer CL, van Loon CJ, de Waal Malefijt MC, van Kampen A. Are surgeons equally satisfied after total knee arthroplasty? Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2004;124:331–333. doi: 10.1007/s00402-004-0655-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brokelman RB, van Loon CJ, Rijnberg WJ. Patient versus surgeon satisfaction after total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:495–498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clifford PE, Mallon WJ. Sports after total joint replacement. Clin Sports Med. 2005;24:175–186. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cordero-Ampuero J, Darder A, Santillana J, Caloto MT, Nocea G. Evaluation of patients’ and physicians’ expectations and attributes of osteoarthritis treatment using Kano methodology. Qual Life Res. 2012;21:1391–1404. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-0058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coulter A, Ellins J. Effectiveness of strategies for informing, educating, and involving patients. BMJ. 2007;335:24–27. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39246.581169.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D’Lima D, Fregly BJ, Patil S, Steklov N, Colwell CW. Knee joint forces: prediction, measurement, and significance. Proc Inst Mech Eng H. 2012;226:95–102. doi: 10.1177/0954411911433372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dubs L, Gschwend N, Munzinger U. Sport after total hip-arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1983;101:161–169. doi: 10.1007/BF00436765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dy CJ, Gonzalez Della Valle A, York S, Rodriguez JA, Sculco TP, Ghomrawi HM. Variations in surgeons’ recovery expectations for patients undergoing total joint arthroplasty: a survey of the AAHKS Membership. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28:401–405. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2012.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gandhi R, Davey JR, Mahomed N. Patient expectations predict greater pain relief with joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:716–721. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghomrawi HM, Franco Ferrando N, Mandl LA, Do H, Noor N, Gonzalez Della Valle A. How often are patient and surgeon recovery expectations for total joint arthroplasty aligned? Results of a pilot study. HSS J. 2011;7:229–234. doi: 10.1007/s11420-011-9203-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Groeneveld P, Kwoh C, Mor M, Appelt C, Geng M, Gutierrez JC, Wessel DS, Ibrahim SA. Racial differences in expectations of joint replacement surgery outcomes. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:730–737. doi: 10.1002/art.23565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gschwend N, Frei T, Morscher E, Nigg B, Loehr J. Alpine and cross-country skiing after total hip replacement: 2 cohorts of 50 patients each, one active, the other inactive in skiing, followed for 5–10 years. Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71:243–249. doi: 10.1080/000164700317411825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haworth RJ, Hopkins J, Ells P, Ackroyd CE, Mowat AG. Expectations and outcome of total hip replacement. Rheumatol Rehabil. 1981;20:65–70. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/20.2.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Healy WL, Iorio R, Lemos MJ. Athletic activity after joint replacement. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29:377–388. doi: 10.1177/03635465010290032301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hepinstall MS, Rutledge JR, Bornstein LJ, Mazumdar M, Westrich GH. Factors that impact expectations before total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26:870–876. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2010.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hudak PL, McKeever P, Wright JG. The metaphor of patients as customers: implications for measuring satisfaction. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:103–108. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(02)00602-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hutson MM, Blaha JD. Patients’ recall of pre-operative instruction for informed consent for an operation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:160–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones CA, Voaklander DC, Johnston DW, Suarez-Almazor ME. Health related quality of life outcomes after total hip and knee arthroplasties in a community based population. J Rheumatol. 2000;27:1745–1752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jorn LP, Johnsson R, Toksvig-Larsen S. Patient satisfaction, function and return to work after knee arthroplasty. Acta Orthop Scand. 1999;70:343–347. doi: 10.3109/17453679908997822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jourdan C, Poiraudeau S, Descamps S, Nizard R, Hamadouche M, Anract P, Boisgard S, Galvin M, Ravaud P. Comparison of patient and surgeon expectations of total hip arthroplasty. Plos One. 2012;7:e30195–e30195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Kilgus D, Dorey F, Finerman G, Amstutz H. Patient activity, sports participation, and impact loading on the durability of cemented total hip replacements. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;269:25–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kravitz RL. Patients’ expectations for medical care: an expanded formulation based on review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 1996;53:3–27. doi: 10.1177/107755879605300101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuster MS. Exercise recommendations after total joint replacement: a review of the current literature and proposal of scientifically based guidelines. Sports Med. 2002;32:433–445. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200232070-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kutzner I, Heinlein B, Graichen F, Bender A, Rohlmann A, Halder A, Beier A, Bergmann G. Loading of the knee joint during activities of daily living measured in vivo in five subjects. J Biomech. 2010;43:2164–2173. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Langdon IJ, Hardin R, Learmonth ID. Informed consent for total hip arthroplasty: does a written information sheet improve recall by patients? Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2002;84:404–408. doi: 10.1308/003588402760978201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lau RL, Gandhi R, Mahomed S, Mahomed N. Patient satisfaction after total knee and hip arthroplasty. Clin Geriatr Med. 2012;28:349–365. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2012.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lavernia CJ, Alcerro JC, Contreras JS, Rossi MD. Ethnic and racial factors influencing well-being, perceived pain, and physical function after primary total joint arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:1838–1845. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1841-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lieberman JR, Dorey F, Shekelle P, Schumacher L, Thomas BJ, Kilgus DJ, Finerman GA. Differences between patients’ and physicians’ evaluations of outcome after total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:835–838. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199606000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lurie JD, Weinstein JN. Shared decision-making and the orthopaedic workforce. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;385:68–75. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200104000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mahomed NN, Liang MH, Cook EF, Daltroy LH, Fortin PR, Fossel AH, Katz JN. The importance of patient expectations in predicting functional outcomes after total joint arthroplasty. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:1273–1279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mancuso CA, Graziano S, Briskie LM, Peterson MG, Pellicci PM, Salvati EA, Sculco TP. Randomized trials to modify patients’ preoperative expectations of hip and knee arthroplasties. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:424–431. doi: 10.1007/s11999-007-0052-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mancuso CA, Jout J, Salvati EA, Sculco TP. Fulfillment of patients’ expectations for total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:2073–2078. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.01802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mancuso CA, Salvati EA, Johanson NA, Peterson MG, Charlson ME. Patients’ expectations and satisfaction with total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1997;12:387–396. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(97)90194-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mancuso CA, Sculco TP, Salvati EA. Patients with poor preoperative functional status have high expectations of total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18:872–878. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(03)00276-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mancuso CA, Sculco TP, Wickiewicz TL, Jones EC, Robbins L, Warren RF, Williams-Russo P. Patients’ expectations of knee surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:1005–1012. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.83B7.12105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mannion AF, Kämpfen S, Munzinger U, Kramers-de Quervain I. The role of patient expectations in predicting outcome after total knee arthroplasty. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:R139–R139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Marcinkowski K, Wong V, Dignam D. Getting back to the future: a grounded theory study of the patient perspective of total knee joint arthroplasty. Orthop Nurs. 2005;24:202–209. doi: 10.1097/00006416-200505000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McGee MA, Howie DW, Ryan P, Moss JR, Holubowycz OT. Comparison of patient and doctor responses to a total hip arthroplasty clinical evaluation questionnaire. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84:1745–1752. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200210000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McGrory BJ, Stuart MJ, Sim FH. Participation in sports after hip and knee arthroplasty: review of literature and survey of surgeon preferences. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:342–348. doi: 10.4065/70.4.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miner AL, Lingard EA, Wright EA, Sledge CB, Katz JN. Knee range of motion after total knee arthroplasty: how important is this as an outcome measure? J Arthroplasty. 2003;18:286–294. doi: 10.1054/arth.2003.50046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moran M, Khan A, Sochart DH, Andrew G. Expect the best, prepare for the worst: surgeon and patient expectation of the outcome of primary total hip and knee replacement. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2003;85:204–206. doi: 10.1308/003588403321661415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Muniesa JM, Marco E, Tejero M, Boza R, Duarte E, Escalada F, Cáceres E. Analysis of the expectations of elderly patients before undergoing total knee replacement. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;51:83–87. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.National Joint Registry for England and Wales. 9th Annual Report. 2012. Available at: http://www.njrcentre.org.uk. Accessed February 14, 2013.

- 53.Nilsdotter AK, Toksvig-Larsen S, Roos EM. Knee arthroplasty: are patients’ expectations fulfilled? A prospective study of pain and function in 102 patients with 5-year follow-up. Acta Orthop. 2009;80:55–61. doi: 10.1080/17453670902805007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Noble PC, Conditt MA, Cook KF, Mathis KB. The John Insall Award. Patient expectations affect satisfaction with total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;452:35–43. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000238825.63648.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Noble PC, Scuderi GR, Brekke AC, Sikorskii A, Benjamin JB, Lonner JH, Chadha P, Daylamani DA, Scott WN, Bourne RB. Development of a new Knee Society scoring system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:20–32. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-2152-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ollivier M, Frey S, Parratte S, Flecher X, Argenson JN. Does impact sport activity influence total hip arthroplasty durability? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:3060–3066. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2362-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reynolds M. No news is bad news—patients’ views about communication in hospital. Br Med J. 1978;1:1673–1676. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6128.1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Richards J, McDonald P. Doctor-patient communication in surgery. J R Soc Med. 1985;78:922–924. doi: 10.1177/014107688507801109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Robinson G, Merav A. Informed consent: recall by patients tested postoperatively. Ann Thorac Surg. 1976;22:209–212. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(10)64904-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schmalzried TP, Shepherd EF, Dorey FJ, Jackson WO, Fa’vae F, dela Rosa M, McKellop HA, McClung CD, Martell J, Moreland JR, Amstutz HC. The John Charnley Award. Wear is a function of use, not time. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;381:36–46. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200012000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Scott CE, Bugler KE, Clement ND, MacDonald D, Howie CR, Biant LC. Patient expectations of arthroplasty of the hip and knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94:974–981. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B7.28219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Scott CE, Howie CR, MacDonald D, Biant LC. Predicting dissatisfaction following total knee replacement: a prospective study of 1217 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92:1253–1258. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.92B9.24394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sewitch MJ, Abrahamowicz M, Dobkin PL, Tamblyn R. Measuring differences between patients’ and physicians’ health perceptions: the patient-physician discordance scale. J Behav Med. 2003;26:245–264. doi: 10.1023/A:1023412604715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Soin B, Thomson HJ, Smellie WA. Informed consent: a case for more education of the surgical team. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1993;75:62–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stevens M, Reininga IH, Bulstra SK, Wagenmakers R, Akker-Scheek I. Physical activity participation among patients after total hip and knee arthroplasty. Clin Geriatr Med. 2012;28:509–520. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Swanson EA, Schmalzried TP, Dorey FJ. Activity recommendations after total hip and knee arthroplasty: a survey of the American Association for Hip and Knee Surgeons. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(6 suppl):120–126. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Taylor WR, Heller MO, Bergmann G, Duda GN. Tibio-femoral loading during human gait and stair climbing. J Orthop Res. 2004;22:625–632. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang CJ, Hsieh MC, Huang TW, Wang JW, Chen HS, Liu CY. Clinical outcome and patient satisfaction in aseptic and septic revision total knee arthroplasty. Knee. 2004;11:45–49. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0160(02)00094-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Weiss JM, Noble PC, Conditt MA, Kohl HW, Roberts S, Cook KF, Gordon MJ, Mathis KB. What functional activities are important to patients with knee replacements? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;404:172–188. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200211000-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.White CS, Mason AC, Feehan M, Templeton PA. Informed consent for percutaneous lung biopsy: comparison of two consent protocols based on patient recall after the procedure. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;165:1139–1142. doi: 10.2214/ajr.165.5.7572491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wright JG, Coyte P, Hawker G, Bombardier C, Cooke D, Heck D, Dittus R, Freund D. Variation in orthopedic surgeons’ perceptions of the indications for and outcomes of knee replacement. CMAJ. 1995;152:687–697. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wylde V, Blom A, Dieppe P, Hewlett S, Learmonth I. Return to sport after joint replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:920–923. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.90B7.20614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yoo JH, Chang CB, Kang YG, Kim SJ, Seong SC, Kim TK. Patient expectations of total knee replacement and their association with sociodemographic factors and functional status. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93:337–344. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Youm J, Chenok K, Belkora J, Chan V, Bozic KJ. The emerging case for shared decision making in orthopaedics. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:1907–1912. [Google Scholar]