Short abstract

Measures of mean cartilage thickness over predefined regions in the femoral plate using magnetic resonance imaging have provided important insights into the characteristics of knee osteoarthritis (OA), however, this quantification method suffers from the limited ability to detect OA-related differences between knees and loses potentially important information regarding spatial variations in cartilage thickness. The objectives of this study were to develop a new method for analyzing patterns of femoral cartilage thickness and to test the following hypotheses: (1) asymptomatic knees have similar thickness patterns, (2) thickness patterns differ with knee OA, and (3) thickness patterns are more sensitive than mean thicknesses to differences between OA conditions. Bi-orthogonal thickness patterns were extracted from thickness maps of segmented magnetic resonance images in the medial, lateral, and trochlea compartments. Fifty asymptomatic knees were used to develop the method and establish reference asymptomatic patterns. Another subgroup of 20 asymptomatic knees and three subgroups of 20 OA knees each with a Kellgren/Lawrence grade (KLG) of 1, 2, and 3, respectively, were selected for hypotheses testing. The thickness patterns were similar between asymptomatic knees (coefficient of multiple determination between 0.8 and 0.9). The thickness pattern alterations, i.e., the differences between the thickness patterns of an individual knee and reference asymptomatic thickness patterns, increased with increasing OA severity (Kendall correlation between 0.23 and 0.47) and KLG 2 and 3 knees had significantly larger thickness pattern alterations than asymptomatic knees in the three compartments. On average, the number of significant differences detected between the four subgroups was 4.5 times greater with thickness pattern alterations than mean thicknesses. The increase was particularly marked in the medial compartment, where the number of significant differences between subgroups was 10 times greater with thickness pattern alterations than mean thickness measurements. Asymptomatic knees had characteristic regional thickness patterns and these patterns were different in medial OA knees. Assessing the thickness patterns, which account for the spatial variations in cartilage thickness and capture both cartilage thinning and swelling, could enhance the capacity to detect OA-related differences between knees.

Keywords: cartilage thickness, knee osteoarthritis, morphology, MRI, thickness pattern, thickness shape

Introduction

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) is a major cause of disability in the elderly and significant improvements are required in understanding the etiology and treatment of this condition. In particular, there is a need for a better characterization of cartilage thickness, a central hallmark of knee OA, in asymptomatic and diseased knees, along with more sensitive analysis methods for this structural variable [1–3]. For a long time, the best measure of cartilage thickness was the tibiofemoral joint space width derived from a knee radiograph. However, this technique is two-dimensional and does not allow for a direct visualization of the cartilage and fine-grained analyses of cartilage thickness [4]. More recently, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has replaced radiography, notably because it can visualize articular cartilage with high resolution and is noninvasive [5,6]. In this case, cartilage thickness is usually analyzed by segmenting consecutive MR images to build a three-dimensional thickness map for the cartilage and then mean thickness measurements are performed on the map [4,5,7–9]. While mean thickness measurements have provided important insights into the characteristics of knee OA [6,10], they suffer from a limited ability to detect OA-related differences; specifically, differences between asymptomatic knees and knees at early disease stages [6,11,12]. Furthermore, these measurements do not exploit the full potential of the information available in the three-dimensional femoral thickness maps since the spatial variations in cartilage thickness (i.e., the thickness shape), which has been suggested to be an important marker in knee OA [13], is lost when calculating mean thicknesses. Therefore, there is a possibility to enhance the understanding of cartilage thickness and the ability to detect OA-related differences by analyzing the thickness shape of the femoral cartilage.

The benefit of using the thickness shape to characterize cartilage in the framework of knee OA becomes apparent when considering that cartilage both locally thins and swells during the course of the disease [6,8,11,12,14] and that these focal deteriorations are subject-specific [8]. These local degradations limit the ability of mean thickness measurements to differentiate the cartilage thickness between individuals or between time points because local thinning and swelling cancel each other when mean thicknesses are calculated and support the need to analyze the shape of the cartilage thickness in addition to the mean thickness. By comparing the cartilage thickness shape, it could be possible to enhance the sensitivity to OA-related differences between knees, both because the thickness shape can account for local thinning and swelling and because the thickness shape may be less affected by the natural variation in cartilage thickness among individuals [15,16].

There is evidence that cartilage thickness is heterogeneous on the distal femur based on thickness maps [2,3,5,17], anterior-posterior thickness profiles along the condyles [18], and regional mean thickness measurements [16,19]. However, there remains a paucity of quantitative information about the spatial variation in cartilage thickness on the femur or how regional thickness shapes vary among subjects or during the course of OA. It was recently shown that asymptomatic knees have a characteristic region of thicker cartilage in each of the medial, lateral, and trochlea compartments [20-22]. These regions are of primary interest in a first analysis of the cartilage thickness shape because articular cartilage thickness and metabolism have been shown to locally adapt in response to applied loads [2,23–25], knee loading has been reported to change with OA progression [26–29], and OA-related cartilage lesions have been associated with areas of high mechanical stress [30]. These three regions also agree with typical injury sites and the location of full-thickness lesions in the femoral cartilage [31,32], further supporting their selection for this study.

The preceding discussion indicates that there is a clear need to determine if there are similar regional thickness shapes among asymptomatic femoral cartilages and if comparing knees in terms of thickness shape can enhance the detection of OA-related thickness differences. Thus, the purpose of this study was to design a method to characterize the thickness shape in three previously identified regions of interest by extracting thickness patterns and to test the following hypotheses: (1) the thickness patterns are similar among asymptomatic knees and the inter-knee similarity decreases with increasing OA severity, (2) the differences between the thickness patterns of an individual knee and reference asymptomatic thickness patterns (differences later referred to as “thickness pattern alterations”) increase with increasing OA severity, and (3) thickness pattern alterations are more sensitive than mean thickness measurements to differences between OA conditions.

Methods

Population.

The study included a group of 130 knees that were placed into one of two datasets (see Table 1). The first dataset (training dataset: 50 asymptomatic knees) was used to develop the method to measure the thickness patterns and provided the reference asymptomatic patterns. The second dataset (analysis dataset: 80 knees), consisting of four subgroups of 20 knees each, was used for hypothesis testing. This second dataset included a subgroup of asymptomatic knees and three subgroups of medial OA knees with Kellgren/Lawrence grades (KLG) [33] of 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The KLGs were defined based on conventional weight-bearing extended knee radiographs as follows: KLG 1 = doubtful joint space narrowing and possible osteophytic lipping; KLG 2 = possible joint space narrowing and definite osteophytes; and KLG 3 = definite joint space narrowing, moderate multiple osteophytes, some sclerosis, and possible deformity of bone ends. There were no differences in demographics between the four subgroups of knees in the analysis dataset (p-value for one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test: age = 0.32; height = 0.90; weight = 0.47; body mass index (BMI) = 0.25). The 70 asymptomatic knees in the training and analysis datasets were randomly selected from the right or left knees of 70 different subjects. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and informed written consent was obtained from all subjects prior to data collection.

Table 1.

Population information

| Dataset | Subgroup | Number of knees | Side | Gender | Age (years) | Height (m) | Weight (kg) | BMI (kg/m2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training | Asymptomatic | 50 | 25 L, 25 R | 25 M, 25 F | 35.2 ± 8.4 | 1.71 ± 0.09 | 77.9 ± 13.2 | 26.6 ± 4.2 |

| Analysis | Asymptomatic | 20 | 11 L, 9 R | 10 M, 10 F | 56.3 ± 3.4 | 1.70 ± 0.10 | 75.0 ± 12.0 | 25.8 ± 3.8 |

| KLG 1 | 20 | 8 L, 12 R | 10 M, 10 F | 59.1 ± 9.7 | 1.69 ± 0.08 | 79.2 ± 9.2 | 27.7 ± 2.5 | |

| KLG 2 | 20 | 13 L, 7 R | 11 M, 9 F | 60.8 ± 9.0 | 1.68 ± 0.08 | 77.2 ± 12.5 | 27.2 ± 3.9 | |

| KLG 3 | 20 | 10 L, 10 R | 10 M, 10 F | 59.7 ± 7.8 | 1.70 ± 0.08 | 80.8 ± 14.6 | 28.1 ± 4.4 |

Note: Data are reported as mean ± standard deviation. BMI: body mass index.

Three-Dimensional Cartilage Thickness Map.

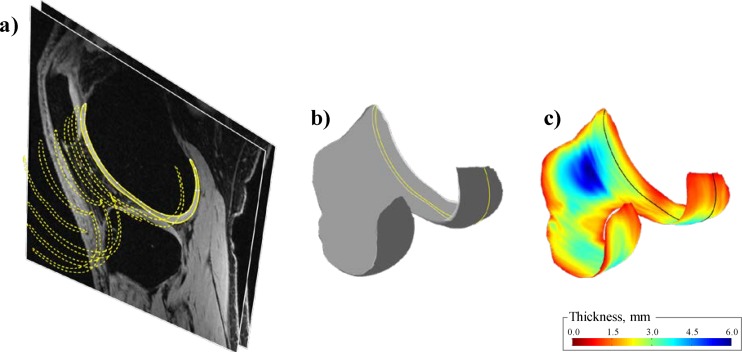

All knees were scanned with a sagittal-plane fat-saturated 3D spoiled gradient recalled echo sequence (3D-SPGR; FOV 140 × 140 mm, in-plane resolution 256 × 256, slice thickness 1.5 mm, 60 slices) using a 1.5 T MRI unit (GE Signa; GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI). The scans were then processed as follows using custom software [5]: (1) the cartilage on the distal femur was manually segmented from each slice by two experienced operators (see Fig. 1(a)), (2) the segmented slices were combined to create a three-dimensional model of the cartilage (see Fig. 1(b)), and (3) a three-dimensional cartilage thickness map was built for the bone-cartilage layer by calculating the minimum distance to the cartilage-synovium layer (see Fig. 1(c)). The accuracy and repeatability of this method was previously reported [5].

Fig. 1.

Illustration of the method used to build the thickness map based MR images. (a) Segmentation of one MR image (solid line) and results from the segmentation of more medial images (dashed lines; 1 slice out of 6 is displayed). (b) Reconstruction of the three-dimensional cartilage model. The plane corresponding to the image segmented in (a) is indicated by a solid line. (c) Thickness map for the bone-cartilage layer. Again, the plane corresponding to the image segmented in (a) is indicated by a solid line.

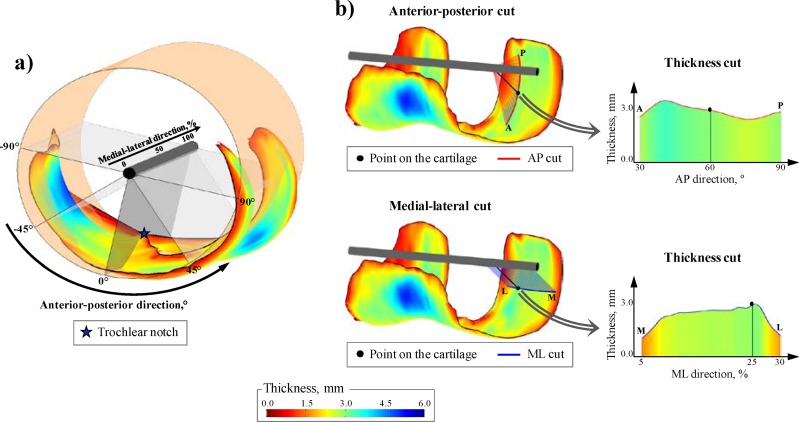

Next, to allow for comparison between knees, the thickness maps were normalized by the fit of a cylinder to the total thickness map (i.e., medial, lateral, and trochlea compartments together) [21,34] (see Fig. 2(a)). Based on the cylinder fit, any point on the thickness map can be located by an anterior-posterior (angle relative to the trochlear notch) and a medial-lateral (percentage of the cartilage width) normalized coordinate (see Fig. 2(a)).

Fig. 2.

(a) Thickness map with superposition of the cylinder fit used to define the coordinate system. (b) Example of thickness cut extraction around a point located 60 deg posterior to the notch and at 25% of the medial-lateral width.

Extraction of Cartilage Thickness Cuts.

To describe the thickness shape in the thicker region of the medial, lateral, and trochlea compartments [20–22], bi-orthogonal thickness cuts were extracted from the thickness map. Thickness cuts were measures of the cartilage thickness along either an anterior-posterior (AP) or a medial-lateral (ML) path around a particular point on the thickness map (see Fig. 2(b)). Anterior-posterior cuts were measured in planes perpendicular to the axis of the cylinder fit and their sizes were defined as angles around the cylinder axis. On the contrary, the medial-lateral cuts were measured in planes parallel to the cylinder axis and their sizes were defined as percentages of the cartilage width.

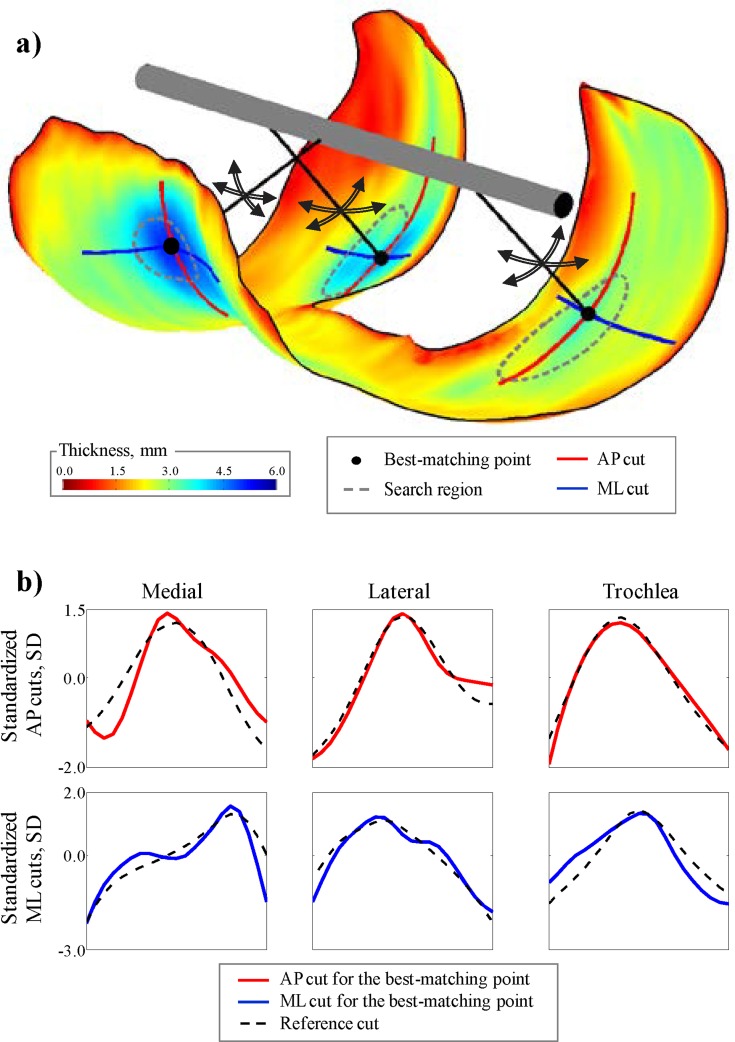

The thickness cuts were not extracted around the same fixed points for every knee because previous reports [20–22] have shown slight variations in the location of the thicker regions among knees (standard deviations between 5 deg and 10 deg for the anterior-posterior direction and between 2% and 3% for the medial-lateral direction) and using the same fixed point for each knee would have confounded the results. Instead, an extraction method based on pattern recognition was developed in order to find the points on each individual thickness map, which provided the bi-orthogonal thickness cuts that best matched reference thickness cuts; the thickness cuts around these individually selected points were then used to describe the regional thickness shape (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Illustration of the thickness cut extraction method. (a) The algorithm searches for the point within the search regions which provides thickness cuts that best match reference thickness cuts. (b) Thickness cuts for the best-matching points in the thickness map displayed in (a) and the reference asymptomatic thickness cuts (obtained with the training dataset) used for the searches.

The extraction method consisted of a training phase (described in the following two paragraphs) during which the bi-orthogonal reference thickness cuts and a search region were determined for each compartment using the 50 asymptomatic knees in the training dataset. Once the reference cuts and the search regions were determined, the method consisted of extracting the thickness cuts for the knees in the analysis dataset without user intervention simply by letting the algorithm find the best-matching points and measure the corresponding thickness cuts. The best-matching points were defined as the points for which the root-mean-square of the difference between the anterior-posterior and medial-lateral cuts around the points and the reference cuts were minimal (see Fig. 3(b)). Thickness amplitude is known to vary among individuals [15–16]; therefore, to make the search for the best-matching points independent of the thickness amplitude, the root-mean-squares were calculated for standardized thickness cuts (i.e., cuts with a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1).

The first step of the training phase consisted of obtaining a trial solution for the reference cuts. This trial solution was obtained by manually identifying the thickest point in the medial, lateral, and trochlea compartments for the 50 knees in the training dataset using a previously described method [21–22]. Anterior-posterior and medial-lateral thickness cuts were then measured around the three points selected in each thickness map. The sizes of the cuts were manually established to capture the characteristic shape of the cartilage thickness in the regions of thicker cartilage. Finally, the trial solution for the reference cuts was obtained by averaging the cuts obtained with the 50 training knees.

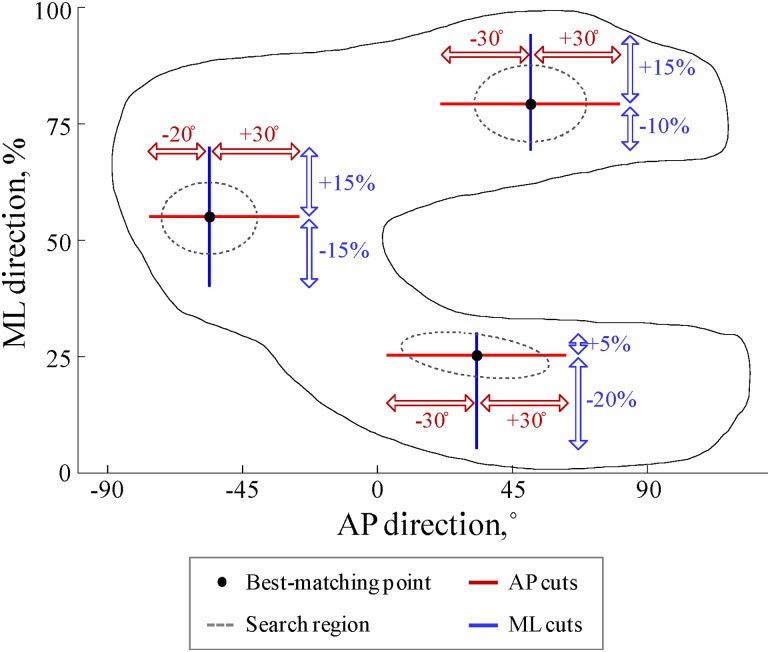

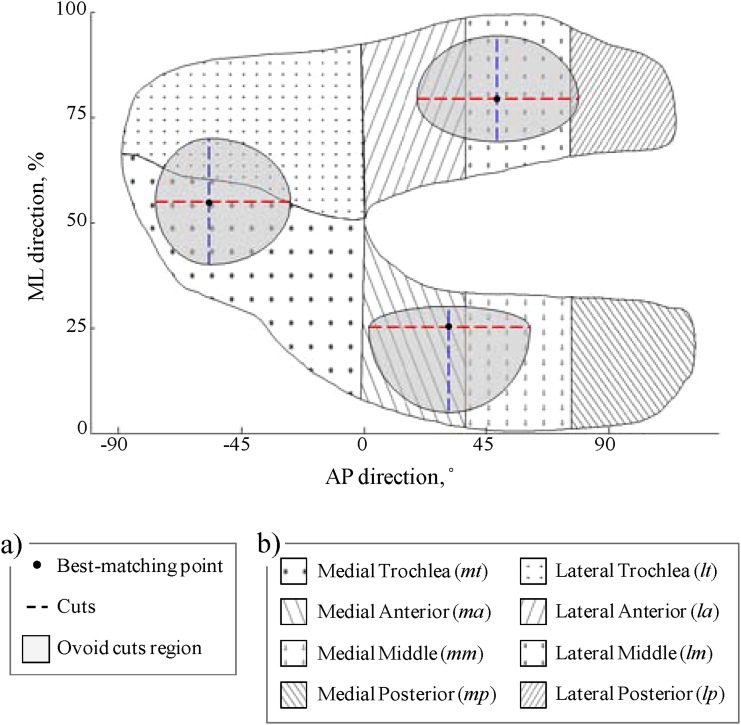

The second and final step of the training phase was an iterative process consisting of: (1) running the algorithm for the 50 training knees using the most recent reference thickness cuts to locate the best-matching points and measure the thickness cuts around these points, (2) averaging the thickness cuts over the 50 knees, and (3) defining the average thickness cuts as the new reference thickness cuts. This process was repeated until all reference cuts remained unchanged between two consecutive iterations (i.e., until the Spearman correlation coefficients between the new reference cuts and the previous reference cuts were larger than 0.99). Finally, in order to ensure that the selected points would come from the same cartilage regions for every knee, three search regions were identified based on the location of the best-matching points of the 50 training knees and the search for the best-matching points for the knees in the analysis dataset was limited to these regions (see Fig. 3).

The sizes of the thickness cuts and the search regions, as determined after the training phase, are presented in Fig. 4. Similarly, the final standardized reference thickness cuts are reported in Fig. 3(b) along with the standardized reference thickness cuts of a typical training knee. In this figure, it can be observed that all six thickness cuts have characteristic forms.

Fig. 4.

Description of the sizes of the thickness cuts and the search regions as determined after the training phase. It is important to note that the best-matching points are located at the center of the search regions in this figure, but that these points can actually be anywhere in the search regions, depending on the individual thickness shape of the knee under analysis. It should also be noted that the search regions agree with the regions of thicker cartilage described in prior studies [20–22].

Hypotheses Testing.

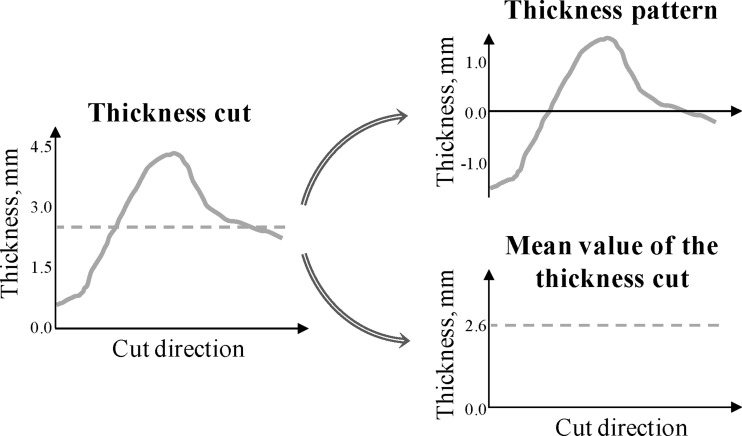

The 80 knees in the analysis dataset were used to test the three hypotheses. For each analysis knee, the anterior-posterior and medial-lateral thickness cuts were obtained in the medial, lateral, and trochlea compartments using the automatic thickness cuts extraction method previously described (and the reference cuts and search regions determined based on the 50 knees in the training dataset). Each thickness cut was then decomposed into a relative (zero-mean) pattern that reflected the thickness shape without the influence of the mean cartilage thickness and into an offset that corresponded to the mean value of the thickness cut (see Fig. 5). For each cut, the thickness pattern was simply obtained by the subtraction of its mean value.

Fig. 5.

Decomposition of a thickness cut into its relative (zero-mean) pattern and its mean value

Hypothesis 1.

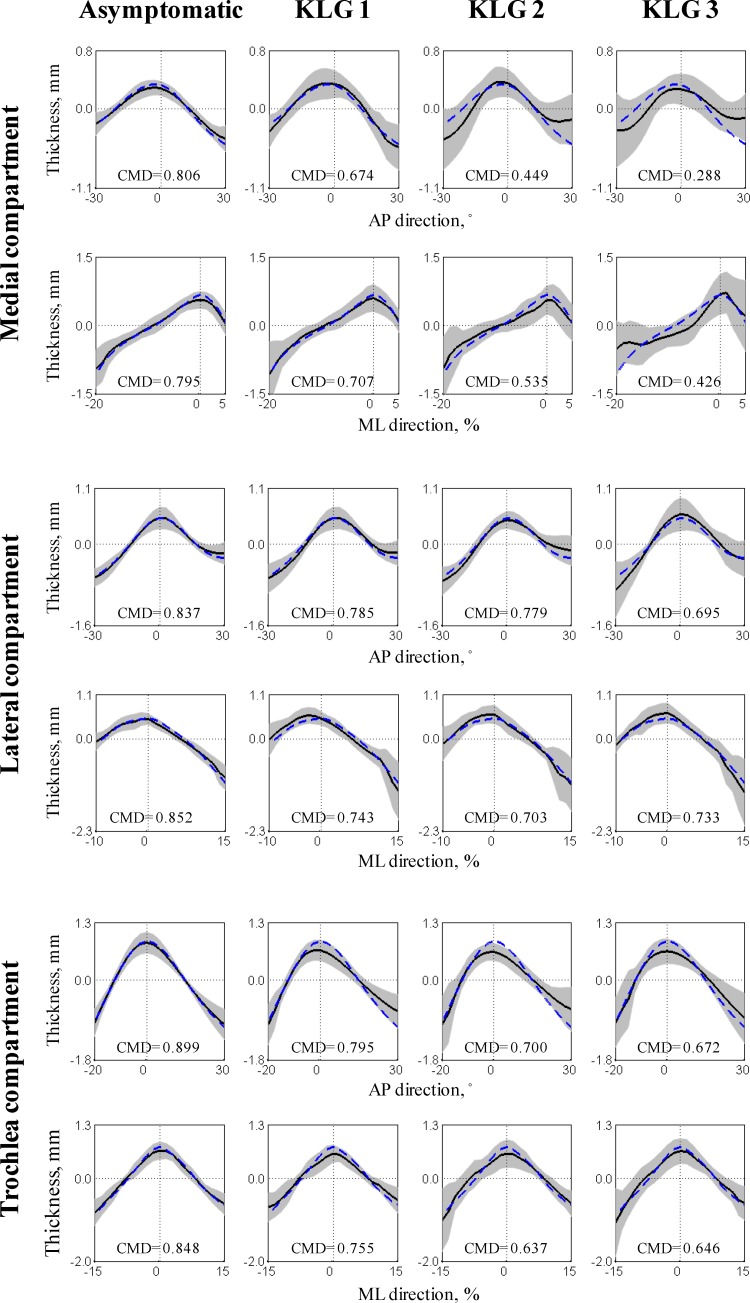

The coefficient of multiple determination (CMD) [35] was used to test the hypothesis that the thickness patterns were similar among asymptomatic knees and that the inter-knee similarity decreased with increasing OA severity. Six coefficients of multiple determination (3 compartments × 2 cut directions) were calculated for each subgroup in the analysis dataset based on the 20 thickness patterns of the knees in the subgroup. The coefficient of multiple determination is frequently used to assess the level of similarity among a set of patterns. It varies between 0, indicating very different patterns among samples and 1, indicating similar patterns for all the samples.

Hypothesis 2.

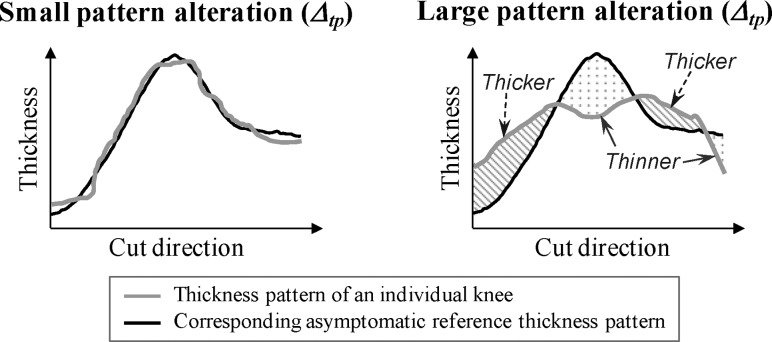

For each pattern, its similarity relative to the corresponding asymptomatic reference pattern was evaluated by calculating the root-mean-square of the difference between the pattern and the corresponding reference pattern (see Fig. 6). Later in this article, this evaluation of similarity is referred as “thickness pattern alteration” (Δtp). The root-mean-square was selected to calculate Δtp because this statistical measure is not sensitive to the sign of the differences, meaning that positive and negative differences along the pattern do not cancel out (see Fig. 6). Next, in order to test the hypothesis that Δtp increases with increasing OA severity, Δtp was calculated for the six patterns (3 compartments × 2 cut directions) of the 80 knees in the analysis dataset and six Kruskal-Wallis tests (one per pattern) were used to determine if Δtp was significantly (p < 0.05) different among the four subgroups. When necessary, these tests were followed by post hoc Wilcoxon rank sum tests with a Bonferroni-adjusted significance level of 0.008 (six comparisons). For exploratory reasons, no adjustment was provided for multiple testing of several compartments and cut directions. Additionally, six Kendall correlation coefficients (3 compartments × 2 cut directions) were calculated between the Δtp and KLG to evaluate the monotonicity of the relationship between alteration values (Δtp) and OA severity. Each coefficient was calculated based on 80 points (one per knee) and the asymptomatic knees were coded as KLG 0 for this calculation.

Fig. 6.

Illustration of the “thickness pattern alteration” (Δtp) metric used to evaluate the similarity between the thickness pattern of an individual knee and the corresponding asymptomatic reference thickness pattern. As depicted in the right plot, Δtp is sensitive to local cartilage thinning and/or thickening that modify the form of the thickness pattern. Note that global cartilage thinning or thickening (i.e., changes in the mean value of the thickness cut) does not affect Δtp.

Hypothesis 3.

To compare the sensitivity of the thickness pattern alterations (Δtp) and mean thickness measurements to differences between OA conditions, the same statistical analysis used in Hypothesis 2 with Δtp (i.e., the Kruskal-Wallis tests and Kendall correlations) was repeated with mean thickness measurements performed on the same 80 analysis knees. The mean values of the thickness cuts (see Fig. 5) were the primary variables for this analysis because they assess the same portions of the cartilage as the thickness pattern alterations. To compare with previous work, the mean thicknesses in the ovoid regions determined by the bi-orthogonal cuts in the three compartments, in eight standard regions of interest [9], and in the entire femur were also analyzed (see Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Illustration of the regions used for the secondary mean thickness measurements. (a) Ovoid regions defined by the size of the bi-orthogonal cuts and centered on the individual best-matching points. (b) A set of eight standard regions of interest [9].

All statistical analyses were done with Matlab version R2010b (Mathworks, MA).

Results

Testing Hypothesis 1 indicated that the asymptomatic subgroup had highly similar patterns with coefficients of multiple determination between 0.80 and 0.90 (see Fig. 8). Inter-knee similarity then decreased almost monotonically with increasing OA severity to reach coefficients of multiple determination between 0.29 and 0.73 for the KLG 3 subgroup.

Fig. 8.

Thickness patterns for the four subgroups in the analysis dataset (n = 20 knees per subgroup). Each graph displays the average (black line) ± one standard deviation (gray area) of a subgroup along with the coefficients of multiple determination (CMD) for the subgroup. For comparison, the reference asymptomatic thickness patterns (obtained with the training dataset) are presented using a blue dashed line.

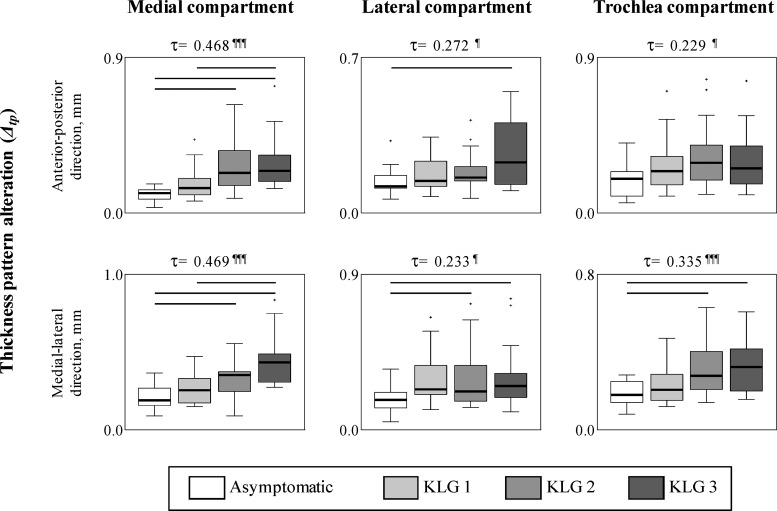

The analyses for Hypothesis 2 showed differences in thickness pattern alterations (Δtp) among the four subgroups (see Fig. 9). In all significant cases, Δtp were higher for the more severe OA subgroups compared to the less severe OA subgroup, indicating that Δtp increased with OA severity. Specifically, for both cut directions in the medial compartment, Δtp were significantly higher for the KLG 2 and 3 subgroups compared to the asymptomatic subgroup, and for the KLG 3 subgroup compared to the KLG 1 subgroup. In the lateral and trochlea compartments, the Δtp in the medial-lateral direction were significantly higher for the KLG 2 and 3 subgroups compared to the asymptomatic subgroup. The KLG 3 subgroup also had significantly higher Δtp compared to the asymptomatic subgroup in the anterior-posterior direction in the lateral compartment. Furthermore, for all compartments and cut directions, the Kendall correlation coefficients (τ) were significant and positive, confirming that knees with more severe OA had higher Δtp. In the medial compartment, where the correlations were stronger (τ > 0.45), there were clear monotonic increases in Δtp with increasing OA severity.

Fig. 9.

Box plots of the thickness pattern alterations (Δtp) for the four subgroups in the analysis dataset. The bars at the top of the boxes indicate significant differences between the subgroups (p < 0.008). The values at the top of the graphs correspond to the Kendall correlation coefficients (τ); the following symbols indicate significant correlations (¶: p < 0.01, ¶¶: p < 0.001, ¶¶¶: p < 0.0001).

Testing Hypothesis 3 indicated that the capacity to detect cartilage thickness differences between subgroups with different disease severities was enhanced when comparing thickness patterns instead of mean thickness measurements. Whereas significant differences in thickness pattern alterations (Δtp) between the asymptomatic and OA subgroups were found as early as KLG 2 in all three compartments (see Fig. 9), the primary mean thickness variables (i.e., the mean values of the thickness cuts) only indicated significant differences in the medial compartment between the KLG 1 and 2 subgroups (see Table 2). The secondary mean thickness measurements generally provided similar results with only one significant difference between subgroups in the medial compartment, sparse significant differences in the lateral compartment except for the lm and lp regions (two significant differences), and no significant differences in the trochlea compartment. Weaker results for the mean thickness measurement compared to the thickness pattern alterations (Δtp) were also noticed when testing the associations with increasing OA severity. With the primary mean thickness measurements, none of the Kendall correlation coefficients were significant in the medial and trochlea compartments (see Table 2) and, on average, the coefficients were more than 70% lower than the coefficients calculated with the corresponding Δtp in these compartments (see Fig. 9). In the lateral compartment, the correlations were comparable between Δtp and the primary mean thickness measurements. In general, the results were similar for the secondary mean thickness measurements (see Table 2) with almost all of the significant correlations in the lateral compartment.

Table 2.

Mean thickness measurements for the subgroups in the analysis dataset

|

Mean thickness measurements in mm |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compartment | Region | Asymptomatic | KLG 1 | KLG 2 | KLG 3 | Kendall correlation (τ) |

| Femur | Total | 1.91 (0.28) | 2.06 (0.30) | 2.03 (0.34) | 2.04 (0.57) | 0.151 |

| Medial | AP thickness cut | 2.29 (0.38) | 2.62 (0.51) | 2.09 (0.41) | 2.20 (0.34) | −0.070 |

| ML thickness cut | 2.01 (0.73) | 2.37 (0.67)3 | 1.99 (0.54)2 | 1.65 (0.72) | −0.120 | |

| Ovoid cuts region | 1.91 (0.57) | 2.26 (0.29) | 2.08 (0.43) | 1.67 (1.06) | −0.126 | |

| ma region | 1.71 (0.29) | 2.02 (0.49) | 1.79 (0.47) | 1.54 (0.67) | −0.139 | |

| mm region | 1.78 (0.48) | 2.07 (0.38) | 2.01 (0.40) | 1.97 (0.73) | 0.042 | |

| mp region | 1.78 (0.38)2 | 1.97 (0.35) | 2.06 (0.42)a | 2.00 (0.59) | 0.220¶ | |

| Lateral | AP thickness cut | 2.32 (0.52) | 2.53 (0.56) | 2.56 (0.50) | 2.83 (0.70) | 0.246¶ |

| ML thickness cut | 2.48 (0.63) | 2.67 (0.75) | 2.54 (0.73) | 2.93 (0.70) | 0.178 | |

| Ovoid cuts region | 2.15 (0.49)3 | 2.32 (0.37) | 2.37 (0.51) | 2.63 (0.68)a | 0.272¶ | |

| la region | 1.55 (0.29) | 1.74 (0.33) | 1.83 (0.37) | 1.83 (0.54) | 0.264¶ | |

| lm region | 1.93 (0.44)1,3 | 2.26 (0.38)a | 2.26 (0.44) | 2.39 (0.69)a | 0.308¶¶ | |

| lp region | 1.75 (0.45)1,3 | 2.11 (0.40)a | 2.06 (0.52) | 2.23 (0.44)a | 0.315¶¶ | |

| Trochlea | AP thickness cut | 3.19 (1.17) | 3.18 (0.92) | 3.00 (0.88) | 3.49 (0.96) | −0.018 |

| ML thickness cut | 3.41 (0.85) | 3.31 (0.71) | 3.13 (0.77) | 3.47 (0.78) | −0.086 | |

| Ovoid cuts region | 3.04 (0.56) | 3.13 (0.80) | 2.71 (0.84) | 3.06 (0.99) | −0.027 | |

| mt region | 2.15 (0.23) | 2.32 (0.35) | 2.22 (0.47) | 2.31 (0.82) | 0.010 | |

| lt region | 2.05 (0.38) | 2.15 (0.48) | 2.12 (0.57) | 2.21 (0.66) | 0.125 | |

Note: Mean thicknesses are reported as median (interquartile range) over the 20 knees in a subgroup.

1, 2, 3 denote significantly different from the asymptomatic, KLG 1, KLG 2, and KLG 3 subgroups, respectively (p < 0.008).

¶, ¶¶, ¶¶¶ denote significant correlations (p < 0.01, p < 0.001, and p < 0.0001).

Discussion

This study improved the spatial characterization of femoral cartilage thickness in relation to knee OA and introduced a promising method to analyze thickness shape. In particular, this study showed that the anterior-posterior and medial-lateral thickness patterns extracted from the medial, lateral, and trochlea compartments were similar among asymptomatic knees and the variations among knees were larger in subgroups with more severe OA, thus supporting the first hypothesis. This observation agrees with previous analyses of mean thickness measurements suggesting that the changes in cartilage thickness due to OA are not spatially uniform and that they involve both focal cartilage thinning and swelling [6,8,11,12,14]. Additionally, while recent reports [20–22] showed that there are characteristic regions of thicker femoral cartilage in asymptomatic knees, this study provided new insights into the nature of the thickness shape in these regions. The fact that asymptomatic knees displayed characteristic thickness patterns is an important finding because it indicates that the regional variations of cartilage thickness on the femoral plate are not random and thus could provide additional means of analyzing cartilage morphology.

As hypothesized, the thickness pattern alterations (Δtp) increased with increasing OA severity, confirming the interpretation that thickness patterns degenerate with increasing OA severity. The differences in Δtp among subgroups and the relationships between Δtp and disease severity, assessed by the Kendall correlations (τ), were smaller in the lateral and trochlea compartments compared to the medial compartment. This difference among compartments is probably due to the selection of medial OA knees for this study and stronger results in the lateral and trochlea compartments are expected with other types of knee OA.

The third hypothesis was also supported since mean thickness measurements were not as sensitive as thickness pattern alterations (Δtp) to OA-related differences in cartilage thickness. The number of significant differences among subgroups was higher for Δtp than for the mean thickness measurements in the three compartments and the Kendall coefficients (τ) indicated a stronger correlation with the KLG for Δtp than for the mean thickness measurements in the medial and trochlea compartments. In the medial compartment, where the disease has been clinically identified for the knees in this study, Δtp increased monotonically with increasing disease severity, suggesting that Δtp might be able to detect subtle OA-related thickness differences even if the disease response is different for every knee. Again, the stronger differences among subgroups in the medial compartment were probably due to the selection of medial OA knees for this study and similar results are expected in the lateral and trochlea compartments with other types of knee OA. The differences in sensitivity between Δtp and mean thickness measurements can be explained by the fact that the simultaneous cartilage thinning and swelling that occur with OA cancel out when mean thickness is calculated, but they are additive when analyzing the thickness pattern alteration. As shown in this study, the similarity between the thickness patterns of asymptomatic knees is high, whereas mean thickness measurements are known to vary substantially between asymptomatic subjects [14,15]. These differences in inter-subject variability may also explain the difference in sensitivity between pattern alterations and mean thickness measurements. While this study considered several mean thickness measurements, some analyzing the same portion of cartilage as the thickness patterns and some analyzing standard cartilage regions [9], it is important to mention that calculating mean thicknesses over other regions could have resulted in higher sensitivity. Nevertheless, the sensitivity obtained with the mean thickness measurements in this study agrees with the limited sensitivity previously reported for comparable measurements [6,11,12].

In this study, a method was introduced to extract bi-orthogonal thickness cuts without user intervention. This method looked for the cartilage points with the surrounding standardized thickness cuts that best matched reference standardized thickness cuts. By doing so, the method allowed for robust thickness cut extraction. Moreover, since the references for the cut extraction and for the quantification of the thickness pattern alterations (Δtp) were the same, when looking for the best-matching points the extraction method was also looking for the points with the smallest Δtp. This means that the Δtp results in Fig. 9 are conservative evaluations and that these results cannot be attributed to a methodological bias. Moreover, it is worth mentioning that the training phase, during which the reference thickness cuts and the search regions were defined, only needs to be performed once and, once these elements have been defined, the localization of the best-matching points, the extraction of the thickness cuts, and the calculation of the thickness pattern alterations are fully automatic. Therefore, while the method described in this study to analyze the thickness shape might involve more computational resources than algorithms used for mean thickness measurements, the amount of work to analyze a knee is the same for both types of analysis and mainly consists of segmenting the MR images to reconstruct the thickness map (see Fig. 1). Several regions of interest have been proposed for mean thickness measurements [4,5,7–9], and the method can be adapted to characterize the thickness shape in these regions rather than in the regions of thicker cartilage, as done in the present study.

One limitation of this study is that it was a cross-sectional design and included knees with medial OA only. While medial OA is more frequent than lateral OA [36], further studies are necessary to extend these results to all types of OA. Similarly the KLG, a general evaluation of the knee OA condition, was used to form the subgroups of knees because this is a common classification and because there is no sensitive metric specific to cartilage thickness; therefore, longitudinal studies are required to fully assess the potential of thickness patterns in OA research as a complementary metric to the KLG. Future studies should also determine the reproducibility (test/retest) of the thickness patterns. The limited number of knees per subgroup in the analysis dataset might appear as another limitation. Although increasing the number of knees per subgroup would certainly strengthen the differences among subgroups and the correlations between the thickness measurements and the KLG, this increase should not affect the conclusions of the study that asymptomatic knees have similar thickness patterns, that thickness pattern alterations increase with OA severity, and that mean thickness measurements are less sensitive than thickness pattern alterations. Furthermore, the modest differences in mean thickness measurements between subgroups generally agree with prior literature [14,37,38]. As a first step toward the analysis of the shape of the cartilage thickness, this study considered anterior-posterior and medial-lateral thickness patterns. The main motivations for this choice were that it facilitates the normalization process and allows for an objective comparison with mean thickness measurements. Finally, while this first study of thickness shape focused on three regions selected based on previous publications [2,20–32], the method is not limited to these regions. Future work should, therefore, also analyze regions that are less frequently discussed in the OA literature.

In conclusion, this study showed that asymptomatic knees had similar characteristic femoral cartilage thickness patterns and that the patterns were different in medial OA knees. Quantifying the pattern alteration allowed for the detection of subtle OA-related variations in cartilage thickness that increased monotonically with disease severity, especially in the medial compartment. Therefore, this study showed that the thickness shape contains important information that can enhance the comparison between knees, notably at early disease stages, and suggested that in the future, the analysis of cartilage thickness should not be limited to mean thickness measurements. Moreover, the results of this study suggest that further research is needed to understand the basis for these regional characteristic thickness shapes and the association with the biological structure of cartilage.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by Grant No. 5R01-AR039421 from the National Institute of Arthritis, Musculoskeletal, and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), by a Merit Review Grant No. A6650R from the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), and by Grant No. PBELB3-125438 from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF).

Contributor Information

Julien Favre, e-mail: jfavre@stanford.edu .

Sean F. Scanlan, e-mail: scanlansean@gmail.com, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Stanford University, Durand Building 061, 496 Lomita Mall, Stanford, CA 94305-4308

Jenifer C. Erhart-Hledik, e-mail: jerhart@stanford.edu

Katerina Blazek, e-mail: kblazek@stanford.edu, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Stanford University, Durand Building 061, 496 Lomita Mall, Stanford, CA 94305-4308;; Center for Tissue Regeneration, Repair, and Restoration, Veterans Administration Hospital, 3801 Miranda Avenue, Palo Alto, CA 94304-1207

Thomas P. Andriacchi, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Stanford University, Durand Building 227, 496 Lomita Mall, Stanford, CA 94305-4308; Center for Tissue Regeneration, Repair, and Restoration, Veterans Administration Hospital, 3801 Miranda Avenue, Palo Alto, CA 94304-1207; Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Stanford University, Durand Building 227, 496 Lomita Mall, Stanford, CA 94305-4308, e-mail: tandriac@stanford.edu

References

- [1]. Andriacchi, T. P. , Mundermann, A. , Smith, R. L. , Alexander, E. J. , Dyrby, C. O. , and Koo, S. , 2004, “A Framework for the in Vivo Pathomechanics of Osteoarthritis of the Knee,” Ann. Biomed. Eng., 32, pp. 447–457. 10.1023/B:ABME.0000017541.82498.37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2]. Adam, C. , Eckstein, F. , Milz, S. , and Putz, R. , 1998, “The Distribution of Cartilage Thickness Within the Joints of the Lower Limb of Elderly Individuals,” J. Anat., 193, pp. 203–214. 10.1046/j.1469-7580.1998.19320203.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3]. Cohen, Z. A. , Mow, V. C. , Henry, J. H. , Levine, W. N. , and Ateshian, G. A. , 2003, “Templates of the Cartilage Layers of the Patellofemoral Joint and Their Use in the Assessment of Osteoarthritis Cartilage Damage,” Osteoarthritis Cartilage, 11, pp. 569–579. 10.1016/S1063-4584(03)00091-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4]. Wirth, W. , and Eckstein, F. , 2008, “A Technique for Regional Analysis of Femorotibial Cartilage Thickness Based on Quantitative Magnetic Resonance Imaging,” IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging, 27, pp. 737–744. 10.1109/TMI.2007.907323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5]. Koo, S. , Gold, G. E. , and Andriacchi, T. P. , 2005, “Considerations in Measuring Cartilage Thickness Using MRI: Factors Influencing Reproducibility and Accuracy,” Osteoarthritis Cartilage, 13, pp. 782–789. 10.1016/j.joca.2005.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6]. Eckstein, F. , and Wirth, W. , 2011, “Quantitative Cartilage Imaging in Knee Osteoarthritis,” Arthritis, 2011, 19 pages. 10.1155/2011/475684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7]. Buck, R. J. , Wyman, B. T. , Hellio Le Graverand, M. P. , Wirth, W. , and Eckstein, F. , 2010, “An Efficient Subset of Morphological Measures for Articular Cartilage in the Healthy and Diseased Human Knee,” Magn. Reson. Med., 63, pp. 680–690. 10.1002/mrm.22207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8]. Buck, R. J. , Wyman, B. T. , Hellio Le Graverand, M. P. , Hudelmaier, M. , Wirth, W. , and Eckstein, F. , 2010, “Osteoarthritis May Not be a One-Way-Road of Cartilage Loss—Comparison of Spatial Patterns of Cartilage Change Between Osteoarthritic and Healthy Knees,” Osteoarthritis Cartilage, 18, pp. 329–335. 10.1016/j.joca.2009.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9]. Pelletier, J. P. , Raynauld, J. P. , Berthiaume, M. J. , Abram, F. , Choquette, D. , Haraoui, B. , Beary, J. , Cline, G. A. , Meyer, J. M. , and Martel-Pelletier, J. , 2007, “Risk Factors Associated With the Loss of Cartilage Volume on Weight-Bearing Areas in Knee Osteoarthritis Patients Assessed by Quantitative Magnetic Resonance Imaging: A Longitudinal Study,” Arthritis Res. Ther., 9, p. R74. 10.1186/ar2272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10]. Eckstein, F. , Cicuttini, F. , Raynauld, J. P. , Waterton, J. C. , and Peterfly, C. , 2006, “Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of Articular Cartilage in the Knee Osteoarthritis (OA): Morphological Assessment,” Osteoarthritis Cartilage, 12(Suppl.), pp. 46–75. 10.1016/j.joca.2006.02.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11]. Reichenbach, S. , Yang, M. , Eckstein, F. , Niu, J. , Hunter, D. J. , McLennan, C. E. , Guermazi, A. , Roemer, F. , Hudelmaier, M. , Aliabadi, P. , and Felson, D. T. , 2010, “Does Cartilage Volume or Thickness Distinguish Knees With and Without Mild Radiographic Osteoarthritis? The Framingham Study,” Ann. Rheum. Dis., 69, pp. 143–149. 10.1136/ard.2008.099200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12]. Hunter, D. J. , Li, L. , Zhang, Y. Q. , Totterman, S. , Tamez, J. , Kwohl, C. K. , Eaton, C. B. , Hellio Le Graverand, M. P. , and Beals, C. R. , 2010, “Region of Interest Analysis: By Selecting Regions With Denuded Areas Can We Detect Greater Amounts of Change?,” Osteoarthritis Cartilage, 18, pp. 175–183. 10.1016/j.joca.2009.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13]. Andriacchi, T. P. , 2013, “Valgus Alignment and Lateral Compartment Knee OA: A Biomechanical Paradox or New Insight Into Knee OA?,” Arthritis Rheum., 65, pp. 310–313. 10.1002/art.37724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14]. Forbell, R. B. , Nevitt, M. C. , Hudelmaier, M. , Wirth, W. , Wyman, B. T. , Benichou, O. , Dreher, D. , Davies, R. , Lee, J. H. , Baribaud, F. , Gimona, A. , and Eckstein, F. , 2010, “Femorotibial Subchondral Bone Area and Regional Cartilage Thickness: A Cross-Sectional Description in Healthy Reference Cases and Various Radiographic Stages of Osteoarthritis in 1,003 Knees From the Osteoarthritis Initiative,” Arthritis Care Res., 62, pp. 1612–1623. 10.1002/acr.20262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15]. Eckstein, F. , Winzheimer, M. , Hohe, J. , Englmeier, K. H. , and Reiser, M. , 2001, “Interindividual Variability and Correlation Among Morphological Parameters of Knee Joint Cartilage Plates: Analysis With Three-Dimensional MR Imaging,” Osteoarthritis Cartilage, 9, pp. 101–111. 10.1053/joca.2000.0365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16]. Eckstein, F. , Yang, M. , Guermazi, A. , Roemer, F. W. , Hudelmaier, M. , Picha, K. , Baribaud, F. , Wirth. W., and Felson, D. T. , 2010, “Reference Values and Z-scores for Subregional Femorotibial Cartilage Thickness—Results From a Large Population-Based Sample (Framingham) and Comparison With the Non-Exposed Osteoarthritis Initiative Reference Cohort,” Osteoarthritis Cartilage, 18, pp. 1275–1283. 10.1016/j.joca.2010.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17]. Eckstein, F. , Gavazzeni, A. , Sittek, H. , Haubner, M. , Lösch, A. , Milz, S. , Englmeier, K. H. , Schulte, E. , Putz, R. , and Reiser, M. , 1996, “Determination of Knee Joint Cartilage Thickness Using Three-Dimensional Magnetic Resonance Chondro-Crassometry (3D MR-CCM),” Magn. Reson. Med., 36, pp. 256–265. 10.1002/mrm.1910360213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18]. Connolly, A. , FitzPatrick, D. , Moulton, J. , Lee, J. , and Lerner, A. , 2008, “Tibiofemoral Cartilage Thickness Distribution and Its Correlation With Anthropometric Variables,” Proc. Inst, Mech. Eng., Part H: J. Eng. Med., 222, pp. 29–39. 10.1243/09544119JEIM306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19]. Li, G. , Park, S. E. , Defrate, L. E. , Schutzer, M. E. , Ji, L. , Gill, T. J. , and Rubash, H. E. , 2005, “The Cartilage Thickness Distribution in the Tibiofemoral Joint and its Correlation With Cartilage-to-Cartilage Contact,” Clin. Biomech. (Bristol, Avon), 20, pp. 736–744. 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2005.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20]. Koo, S. , Rylander, J. H. , and Andriacchi, T. P. , 2011, “Knee Joint Kinematics During Walking Influences the Spatial Cartilage Thickness Distribution in the Knee,” J. Biomech., 44, pp. 1405–1409. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.11.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21]. Scanlan, S. F. , Favre, J. , and Andriacchi, T. P. , 2013, “The Relationship Between Peak Knee Extension at Heel-Strike of Walking and the Location of Thickest Femoral Cartilage in ACL Reconstructed and Healthy Contralateral Knees,” J. Biomech., 46, pp. 849–854. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2012.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22]. Favre, J. , Blazek, K. , Erhart, J. C. , and Andriacchi, T. P. , 2012, “Characterization of the Spatial Cartilage Thickness Distribution on the Distal Femur in Healthy Knees,” Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Orthopeadic Research Society, San-Francisco, CA, pp. 1795. [Google Scholar]

- [23]. Chaudhari, A. M. W. , Briant, P. L. , Bevill, S. L. , Koo, S. , and Andriacchi, T. P. , 2008, “Knee Kinematics, Cartilage Morphology and Osteoarthritis After ACL Injury,” Med. Sci. Sports Exercise, 40, pp. 215–222. 10.1249/mss.0b013e31815cbb0e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24]. Bevill, S. L. , Briant, P. L. , Levenston, M. E. , and Andriacchi, T. P. , 2009, “Central and Peripheral Region Tibial Plateau Chondrocytes Respond Differently to in Vitro Dynamic Compression,” Osteoarthritis Cartilage, 17, pp. 980–987. 10.1016/j.joca.2008.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25]. Andriacchi, T. P. , Koo, S. , and Scanlan, S. F. , 2009, “Gait Mechanics Influence Healthy Cartilage Morphology and Osteoarthritis of the Knee,” J. Bone Jt. Surg., Am., 91, pp. 95–101. 10.2106/JBJS.H.01408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26]. Creaby, M. W. , Wang, Y. , Bennell, K. L. , Hinman, R. S. , Metcalf, B. R. , Bowles, K. A. , and Cicuttini, F. M. , 2010, “Dynamic Knee Loading is Related to Cartilage Defects and Tibial Plateau Bone Area in Medial Knee Osteoarthritis,” Osteoarthritis Cartilage, 18, pp. 1380–1388. 10.1016/j.joca.2010.08.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27]. Sharma, L. , Hurwitz, D. E. , Thonar, E. J. , Sum, J. A. , Lenz, M. E. , Dunlop, D. D. , Schnitzer, T. J. , Kirwan-Mellis, G. , and Andriacchi, T. P. , 1998, “Knee Adduction Moment, Serum Hyaluronan Level, and Disease Severity in Medial Tibiofemoral Osteoarthritis,” Arthritis Rheum., 41, pp. 1233–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28]. Favre, J. , Hayoz, M. , Erhart-Hledik, J. C. , and Andriacchi, T. P. , 2012, “A Neural Network Model to Predict Knee Adduction Moment During Walking Based on Ground Reaction Force and Anthropometric Measurements,” J. Biomech., 45, pp. 692–698. 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2011.11.057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29]. Miyazaki, T. , Wada, M. , Kawahara, H. , Sato, M. , Baba, H. , and Shimada, S. , 2002, “Dynamic Load at Baseline Can Predict Radiographic Disease Severity in Medial Compartment Knee Osteoarthritis,” Ann. Rheum. Dis., 61, pp. 617–622. 10.1136/ard.61.7.617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30]. Wirth, W. , Benichou, O. , Kwoh, C. K. , Guermazi, A. , Hunter, D. , Putz, R. , and Eckstein, F. , 2010, “Spatial Patterns of Cartilage Loss in the Medial Femoral Condyle in Osteoarthritic Knees: Data From the Osteoarthritis Initiative,” Magn. Reson. Med., 63, pp. 574–581. 10.1002/mrm.22194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31]. Ahmad, C. S. , Cohen, Z. A. , Levine, W. N. , Ateshian, G. A. , and Mow, V. C. , 2001, “Biomechanical and Topographic Considerations for Autologous Osteochondral Grafting in the Knee,” Am. J. Sports Med., 29, pp. 201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32]. Gulati, A. , Chau, R. , Beard, D. J. , Price, A. J. , Gill, H. S. , and Murray, D. W. , 2009, “Localization of the Full-Thickness Cartilage Lesions in Medial and Lateral Unicompartmental Knee Osteoarthritis,” J. Orthop. Res., 27, pp. 1339–1346. 10.1002/jor.20880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33]. Kellgren, J. H. , and Lawrence, J. S. , 1957, “Radiological Assessment of Osteoarthritis,” Ann. Rheum. Dis., 16, pp. 494–502. 10.1136/ard.16.4.494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34]. Kauffmann, C. , Gravel, P. , Godbout, B. , Gravel, A. , Beaudoin, G. , Raynauld, J. P. , Martel-Pelletier, J. , Pelletier, J. P. , and de Guise, J. A. , 2003, “Computer-Aided Method for Quantification of Cartilage Thickness and Volume Changes Using MRI: Validation Study Using a Synthetic Model,” IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng., 50, pp. 978–988. 10.1109/TBME.2003.814539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35]. Neter, J. , Wasserman, W. , and Kunter, M. H. , 1985, Applied Linear Statistical Models: Regression, Analysis of Variance, and Experimental Designs, Irwin series in statistics, Irwin, ed., Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- [36]. Ahlback, S. , 1968, “Osteoarthrosis of the Knee. A Radiographic Investigation,” Acta Radiologica Diagnosis, 277(Suppl.), pp. 70–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37]. Hellio Le Graverand, M. P. , Buck, R. J. , Wyman, B. T. , Vignon, E. , Mazzuca, S. A. , Brandt, K. D. , Piperno, M. , Charles, H. C. , Hudelmaier, M. , Hunter, D. J. , Jackson, C. , Kraus, V. B. , Link, M. T. , Majumdar, S. , Prasad, P. V. , Schnitzer, T. J. , Vaz, A. , Wirth, W. , Eckstein, F. , 2009, “Subregional Femoral Cartilage Morphology in Women—Comparison Between Healthy Controls and Participants With Different Grades of Radiographic Knee Osteoarthritis,” Osteoarthritis Cartilage, 17, pp. 1177–1185. 10.1016/j.joca.2009.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38]. Eckstein, F. , Nevitt, M. , Gimona, A. , Picha, K. , Lee, J. H. , Davies, R. Y. , Dreher, D. , Benichou, O. , Hellio Le Graverand, M. P. , Hudelmaier, M. , Maschek, S. , and Wirth, W. , 2011, “Rates of Change and Sensitivity to Change in Cartilage Morphology in Healthy Knees and in Knees With Mild, Moderate, and End-Stage Radiographic Osteoarthritis: Results From 831 Participants From the Osteoarthritis Initiative,” Arthritis Care Res., 63, pp. 311–319. 10.1002/art.30414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]