Abstract

Not all biases are equivalent, and not all biases are uniformly negative. Two fundamental dimensions differentiate stereotyped groups in cultures across the globe: status predicts perceived competence, and cooperation predicts perceived warmth. Crossing the competence and warmth dimensions, two combinations produce ambivalent prejudices: pitied groups (often traditional women or older people) appear warm but incompetent, and envied groups (often nontraditional women or outsider entrepreneurs) appear competent but cold. Case studies in ambivalent sexism, heterosexism, racism, anti-immigrant biases, ageism, and classism illustrate both the dynamics and the management of these complex but knowable prejudices.

Keywords: stereotypes, prejudice, discrimination, race, gender, age, class

A middle-aged white man walks into an office … what is your mental image? People assume a lot, right away, sizing each other up, in an instant. Social categories such as gender, race, and age immediately impinge on impressions, whether we like it or not. In today’s global management context, immigrant status, nationality, and social class rapidly shape impressions as well. Beyond these first-millisecond impressions, social categories condition what ensues. First impressions do count. More and more, organizations are expected to know that decision-makers and peers cannot help automatically noticing social categories. What is more, people often act on these categories, unaware of their influence. Decades of research establish these realities (Macrae and Bodenhausen 2000; Fiske 1998).

Evolution argues for the utility of this rapid category-based social judgment. People have to know whom to approach or avoid and for what purposes. Evolution also argues that just a few fundamental principles describe how people understand each other. Knowing these dimensions organizes and informs what may otherwise seem an arbitrary and overwhelming miscellany of group images that could affect diversity management. This article describes two fundamental, apparently universal, dimensions of out-group images, which situate race, gender, and other categories in a larger societal map that predicts stereotypic beliefs, emotional prejudices, and discriminatory tendencies. A novel contribution of this framework is the concept of ambivalent images, applied here particularly to gender bias, heterosexism, racism, anti-immigrant biases, ageism, and classism. Another novel contribution demonstrates the primacy of warmth and trust over sheer status and power, what might be termed a focus on relational capital in management.

Universal Dimensions of Social Cognition

When people encounter an individual or group, they first need to know the “Other’s” intentions, for good or ill. Whether someone walks into your office, approaches you in a dark alley, or sits next to you in public, you need to know immediately whether that Other is benign or harmful. Our ancestors had the same dilemma, and modern citizens especially have the same problem in reaction to new immigrant groups. People have intentions, which set them apart from inanimate objects and help to predict what they will do. The Stereotype Content Model (SCM) calls this first dimension perceived warmth, which includes apparent trustworthiness, friendliness, and sociability (Fiske et al. 2002; Fiske, Cuddy, and Glick 2007). People infer warm (or cold) intent from respectively cooperative or competitive structural relationships between individuals or groups. That is, those groups who cooperate appear warm and trustworthy; those who compete appear cold and untrustworthy, even exploitative. These links are robust (Cuddy, Fiske, and Glick 2008).

Knowing a stranger’s intentions solves only part of the dilemma, because one must know the Other’s capability to enact those intentions. An incompetent foe poses less threat and an incompetent friend offers less benefit than their more competent counterparts. People infer this competence (capability, skill) from apparent status (prestige, economic success) (Cuddy, Fiske, and Glick 2008; Kervyn, Fiske, and Yzerbyt n.d.-b). People all over the world believe in meritocracy (status = competence) to a surprising degree.

Most prior descriptions of group images have focused mainly on either status characteristics (Berger, Cohen, and Zelditch 1972; Ridgeway 1991) or on cooperation-competition (Sherif and Sherif 1953). Combining these two dimensions also goes beyond standard dichotomous in-group/out-group designations (Tajfel 1981). These dimensions emerge from multidimensional scaling (Kervyn, Fiske, and Yzerbyt n.d.-a); in representative and convenience samples; in surveys, experiments, and neuroimaging data; and across countries and time (see Cuddy, Fiske, and Glick 2008).

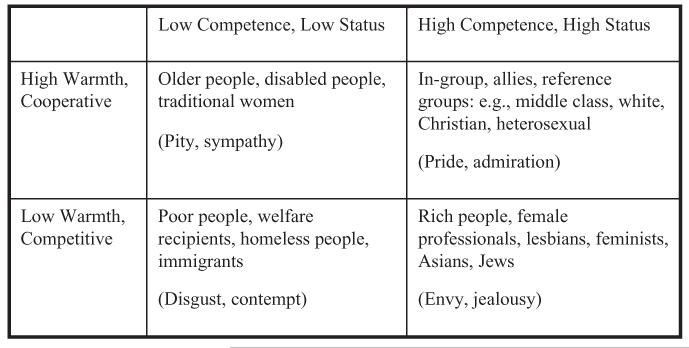

The quadrants reveal systematic clusters that map a society’s images of its groups. As Figure 1 shows, at a cultural level, societal in-groups, allies, and reference groups might include American defaults, such as middle class, white, Christian, and heterosexual. Even those not identified with these groups recognize their hegemony and rate their cultural image as being both warm and competent. A source of pride and admiration, they are viewed as relatively high status and cooperating with society’s goals and values. People willingly help them and associate with them (Cuddy, Fiske, and Glick 2007).

FIGURE 1.

Stereotype Content Model’s Clusters of Groups and Emotional Prejudices

Society’s most extreme out-groups, stereotyped as neither warm nor competent, include poor people and immigrants (all over the world) as well as homeless people and drug addicts (in the United States). Even members of these groups know where they stand in society. Triggering disgust and contempt, they are viewed as extremely low-status and as undermining the values of society. In the current context, note that poor blacks and poor whites, as well as welfare recipients, land here. These groups, opposite to the collective in-groups, are also viewed unambivalently. They allegedly lack both typically human qualities such as sociability and uniquely human qualities such as autonomy, so people effectively dehumanize them, according to self-report and neuroimaging data (Harris and Fiske 2006). People avoid, neglect, and demean them, devaluing their lives relative to those of others (Cikara et al. 2010) and may even attack them (Cuddy, Fiske, and Glick 2007). Not often the purview of white-collar management concerns, these groups enter into blue-collar management concerns, for example, for entry-level service and maintenance work.

Ambivalent Out-Groups

Under the radar, more subtle, unexamined prejudices target groups that elicit mixed biases. Ambivalent out-groups fall into two types, with particular relevance to out-group members in management positions. Mixed out-groups include, first, those seen as nice but incompetent. All over the world, across samples, this includes older people and (where mentioned) people with disabilities. Traditional women land here, in many samples, as do Irish and Italian immigrants in the United States—they all are liked but not especially respected. Recipients of pity and sympathy, they are viewed as low-status but harmless and nice, not exactly management material. Note that pity is an ambivalent emotion, in that it implies a subjectively benign attitude that depends on the target remaining subordinate; that is, pity is paternalistic. These groups receive help, even overhelping, which demonstrably undermines performance (Gilbert and Silvera 1996), as we will see, but people also avoid them socially (Cuddy, Fiske, and Glick 2007). In essence, this inattention is scorn (Fiske 2011). Given the strength of informal networks (Podolny and Baron 1997), social neglect is not trivial in the workplace.

The complementary type of ambivalence identifies other out-groups as competent but cold. All over the world, this includes rich people and ethnicities often seen as outsider entrepreneurs (e.g., Asians and Jews). Nontraditional women land here (female professionals, feminists, lesbians), as do minority professionals and gay professionals. Targets of envy and resentment, these groups are admitted to be high-status but not “one of us,” not on our side (Fiske 2011). Describing resentment of elites, this form of envy explains Schadenfreude (glee at their misfortunes). People are obliged to associate with these groups because they control resources, but they may attack and sabotage them when they can get away with it (Cuddy, Fiske, and Glick 2007; Rudman and Phelan 2008).

The Big Picture

Why does this SCM matter to managing diversity? Not all bias is the same; prejudice is not one-size-fits-all. Ambivalent prejudices are especially hard to detect because they contain mixed beliefs, mixed feelings, and mixed behaviors. Subjectively positive regard (liking or respect) combines with negative reactions (disliking or disrespect). Indeed, such mixed feelings are more common than not. Given information positive on one of the fundamental dimensions, people assume the other is negative, a kind of compensation effect (Kervyn et al. 2009). This helps to justify inequality, with societal beliefs that the poor are happy or the rich are heartless. Consistent with this system-justification view, more income inequality predicts more ambivalent out-group images across twenty countries (Durante et al. n.d.).

Across cultures, the SCM maps societal theories of ethnic, gender, and other social group positions, revealing cultural variations. For example, East Asian samples do not self-promote the in-groups to the high-warmth/high-competence position of Western samples’ in-groups, instead preferring a more neutral self-image in keeping with cultural modesty norms (Cuddy et al. 2009). Nevertheless, East Asia’s rich people, poor people, old people, and immigrants land in the same clusters as in Western samples.

The SCM is not just an artifact of modern multicultural, global societies. It yields descriptively valid data for qualitative analyses of articles from Italian Fascists (Durante, Volpato, and Fiske 2009) and from 1930s American college students, revealing patterns of stereotype change and continuity over time (Bergsieker et al. n.d.). Related dimensions have appeared in prior analyses of interpersonal space (Peeters 2001; Rosenberg, Nelson, and Vivekananthan 1968; Wojciszke, Abele, and Baryla 2009) and attitudinal space (Osgood, Suci, and Tannenbaum 1957; see Fiske, Cuddy, and Glick [2007] for a conceptual comparison and Kervyn and Fiske [n.d.] for an empirical comparison).

Given the apparent universality of the warmth and competence dimensions, they potentially aid understanding the perceived fit between a group’s status or power and its role in an organization. Some organizational roles emphasize status and competence, and groups stereotypically high on these dimensions might seem to fit better. Other organizational roles might require more relational capital, and groups stereotypically high on cooperation, trustworthiness, and warmth might seem to fit well there. Bias can masquerade as perceived lack of fit.

Case Studies

Different management dilemmas accompany different groups, but the SCM provides a systematic window into each group’s unique challenges. The conceptual framework provides practical angles on predictable clusters of groups. Consider gender, sexuality, race/ethnicity, immigrant status, age, and social class.

Ambivalent sexism

Early theories of sexism focused on antifemale sentiments and hostility toward women (e.g., Spence, Helmreich, and Stapp 1973; but presciently, especially competent ones, Spence and Helmreich 1972). This negative framing bumped into the women-are-wonderful effect, showing that women are liked better than men (Eagly, Mladinic, and Otto 1991). Noting these apparent contradictions, a new approach analyzed the relationships between men and women, identifying the unique intergroup combination of societal dominance (by men), common to many in-group/out-group relations, with the intimate interdependence, unique to male-female relations. Ambivalent sexism reflects this duality (Glick and Fiske 1996, 2007). Hostile sexism (HS) targets nontraditional women who threaten male dominance in various ways: female professionals, intellectuals, and trades-women compete for men’s traditional roles; lesbians and vamps reject heterosexual intimacy; and feminists challenge male power. These women are stereotyped as threateningly capable but not nice. In contrast to hostile sexism, subjectively benevolent sexism (BS) protects women who adhere to traditional roles, interdependence, and power relations. These include housewives, secretaries, and “typical” women (Eckes 2002), all viewed as nice but dumb. These two forms of sexism represent ambivalent polarities; one viewing women as warm but incompetent (BS), the other viewing women as competent but not warm (HS).

BS paternalizes compliant women by promising protection and help, but this weakens their autonomy and ability. Benevolent sexist treatment (“all the men will always help you”) distracts women with self-doubt and undermines their performance (Dardenne, Dumont, and Bollier 2007; Dumont, Sarlet, and Dardenne 2010), making them devalue their task competence (Barreto et al. 2010). BS disarms women’s recognition of and resistance to sexism: protective paternalism suffuses women’s experience (Fields, Swan, and Kloos 2010), making them less likely to notice it and to identify it as harmful despite its ill effects (Bosson, Pinel, and Vandello 2010).

BS doubtless helps to explain the working-mother wage penalty of about 5 percent, controlling for all other relevant variables (Benard, Paik, and Correll 2008; Budig and England 2001). Women workers with children seem warmer but less competent than other employees, whereas working fathers gain in warmth without losing competence (Cuddy, Fiske, and Glick 2004). Working mothers are seen as less worth hiring, training, and promoting, even controlling for all else. Women by default are viewed through a caregiver lens, according to the gender-role-congruity theory (Eagly and Karau 2002). Managers worry more about women’s work-life conflicts than about men’s (Hoobler, Wayne, and Lemmon 2009), with women in traditional roles especially paying the price. Women are traditionally lower-status, so they get greater scrutiny in hiring and at work; thus, mothers get less leeway to juggle than fathers do (Correll, Benard, and Paik 2007). BS would help to explain this by the subjectively benign concern about whether the working mother “can handle” everything.

As noted, ambivalent sexism teaches that there are two kinds of women. In the workplace, the nontraditional women suffer the better-known kind of sexism—hostility. Subtypes of women seen as competent but cold include, as just listed, career women, feminists, intellectual women, vamps, and lesbians (Eckes 2002). HS views women as competitors in the workplace and even in the bedroom. In the world of societal empowerment (CEO roles, government positions) and advancement (education, basic rights), countries with higher HS fail to empower and advance women as a group (Glick et al. 2000). In the workplace, HS predicts negative stereotypes of career women (Glick et al. 1997). Consistent with being threatened by female professionals, prescriptive gender stereotypes (implicit beliefs that women should be nice and low-status) predict backlash against agentic (i.e., competent) women (Rudman and Glick 2001; Rudman and Phelan 2008). Agentic, effective women are perceived as highly competent but cold, compared with equally agentic men; what is more, social skills suddenly loom larger than competence in hiring agentic women, unlike all other job candidates (Phelan, Moss-Racusin, and Rudman 2008).

Gender stereotypes are especially sticky because they are prescriptive. Descriptive stereotypes say what a group does; prescriptive ones say what a group should do. When intergroup relations are also interdependent, prescriptive stereotypes flourish. Gender stereotypes are heavily prescriptive (Burgess and Borgida 1999; Fiske and Stevens 1993; Heilman 2001), specifying that traditional women are preferable to nontraditional women, or at least liked better.

Overall, in managing gender issues, organizations must monitor two contrasting kinds of bias against women: the protective but demeaning benevolence, and the threatened but dangerous hostility. Ambivalence strikes again.

A note on heterosexism

Warmth and competence likewise describe types of bias toward gay men (Clausell and Fiske 2005). The more effeminate stereotypic subtypes seem well-intentioned but effectual, whereas the gay-professional subtypes (e.g., artists) seem competent but not warm. Whereas most heterosexism research documents fiercely negative attitudes toward gay men (e.g., Hegarty and Pratto 2001; Herek 2000), understanding some of the ambivalent subtypes may mitigate some of the management issues. For example, although straight-acting gay men are most accepted, and leather-biker gays are despised, at least the stereotypically effeminate gays are liked and the gay professionals are respected. The costs come on the compensating negative dimension. That is, gay men who seem femininemay be disrespected, and openly gay men who seem professional may appear cold.

Racism

In modern times, racism reflects more ambivalence than it did a century ago. Ambivalent racism pits hostile (antiblack) sentiments against subjectively sympathetic but paternalistic (problack) sentiments (Katz and Hass 1988). Ambivalent racism depicts two contrasting reactions by whites toward blacks.

“Problack” attitudes blame black disadvantage on discrimination, segregation, and lack of opportunities. This pole of attitude ambivalence links to humanitarianegalitarian values of kindness, prosociality, equality, and recognizing the power of circumstances. Both correlational studies and priming experiments show this link (Katz and Hass 1988).

In itself, consistent with the SCM, this subjectively problack attitude is ambivalent because it focuses on black disadvantage (disrespecting them all as victims) but also sympathizes with their plight (liking them). However, it fails to acknowledge black resilience, black progress, and the sizable proportion of black Americans who succeed. Thus, it fits the SCM pity quadrant, rather than the admiration-pride quadrant. Pity is an ambivalent emotion, and liking but disrespecting is intrinsically ambivalent.

In contrast, hostile antiblack racism resembles old-fashioned, unambivalent racism, claiming that black people are unambitious, disorganized, free-riding, and do not value education (Katz and Hass 1988). This hostility links to work-ethic beliefs, in both correlational and priming studies: believing that people have excess leisure, that failure reflects a lack of effort, and that work shows strength of character. This hostility harbors no ambivalence, only resentment.

Nevertheless, this work-ethic kind of antiblack racism might allow for more flexibility than a potentially worse genetic-essentialist form of hostile racism. In theory, the perceived work-ethic kind of racism would respond differently to unemployed black people than to professional, successful black people. Indeed, examining American cultural subtypes of black Americans, racial stereotypes do split poor blacks (viewed as neither competent nor warm) from black professionals (competent and almost as warm as the in-groups) (Cuddy, Fiske, and Glick 2007). Even black Americans split their own subtypes by social class (Fiske et al. 2009). The black middle class receives the most admiration.

Thus, the main evidence for racial ambivalence so far provides only a loose fit to the SCM. Black Americans land in two unambivalent but opposite quadrants of SCM space, low on both dimensions or high on both. Black Americans are viewed ambivalently mainly to the extent that white Americans simultaneously harbor a more subjectively positive and a more hostile attitude, which can flip from one polarity to the other, depending on individual differences in beliefs and on situational cues (Katz and Hass 1988).

Another version of ambivalent racial polarity, however, appears in aversive racism (Dovidio and Gaertner 2004). Well-intentioned whites express overtly positive verbal, explicit beliefs about their own egalitarian treatment of black Americans. But whites simultaneously harbor negative, nonverbal, implicit reactions that are detectable not only by researchers (Dovidio, Kawakami, and Gaertner 2002) but also by their black interaction partners (Shelton 2003; Shelton and Richesen 2006).

The implications for managing race are that nonblack managers and employees need to be aware of this ambivalent duality and its subtlety. The bad news is that people typically resist this feedback. The good news is that when whites do try hard to be nonracist, their black partners like them better (Shelton 2003).

Immigrant status

Ethnic stereotypes are accidents of immigration, according to the SCM. Groups emigrate as systematic subsets of their national populations, depending on political, economic, and cultural push factors. Sometimes more privileged, educated segments emigrate, and sometimes less educated physical laborers emigrate. For example, when Chinese immigrants to the United States arrived to build the railroads, their stereotypes revolved around their peasant status in their home country and their work roles here. After later waves of highly e ducated, technically trained Chinese immigrants arrived, their ethnicity’s stereotype contrasted dramatically with the earlier one. Who happens to come and what jobs await them together generalize in observers’ minds to describe the entire ethnicity. (Social role theory makes a similar argument about gender differences and stereotypes [Eagly 1987].) People observe who fills which roles, not without some accuracy, but then they erroneously assume that the roles reflect the predispositions, traits, and abilities of their occupants’ ethnic categories.

Generic immigrants are among the most disliked and disrespected groups in the SCM space, across nations. In the United States, unspecified immigrants are stereotyped as lacking both warmth and competence (Cuddy, Fiske, and Glick 2007), and other countries agree (Cuddy et al. 2009; Durante et al. n.d.). Participants report disgust and contempt, active harm (attacks), and passive harm (neglect) by society—a dire situation.

A closer look shows why. Immigrant stereotypes depend entirely on ethnicity (Lee and Fiske 2006). The only types of immigrants who seem low on both warmth and competence are Latino and African immigrants; all the others receive at least one positive evaluation. Immigrants who are Mexicans, South Americans, Africans, or undocumented rate unambivalently low, and they are associated with farm workers. In contrast, generic European immigrants rate as equal to Americans on both dimensions, and Canadian immigrants rate higher than both, all associated with the middle class. These high-high and low-low immigrant clusters represent the two polarities of immigrant images.

Other immigrants fit the SCM ambivalent clusters: East Asian immigrants seem competent but not warm and are associated with the tech industry. Chinese, Japanese, korean, and generic Asians land here. Indians are the Asian exception, falling in the in-group cluster—shared language may contribute to this.

The other ambivalent cluster for immigrants contains only Italian and Irish immigrants—last century’s waves now seen as harmless and familiar, warm but not highly competent. Within the European Union countries’ mutual stereotypes, these nationalities are viewed the same way (Cuddy et al. 2009). (Within the EU, Germans and the British are seen as competent but cold.)

For immigrants, the most obvious bridges to acceptance ought to be documentation, language, and generational longevity. Indeed, generic documented immigrants and third-generation immigrants land in the in-group cluster. English-speaking ethnicities (Canadians, Irish, Indians) fare better than non-native English speakers (Latinos, East Asians). Nevertheless, ethnicity trumps documentation and generational longevity, with these factors improving the perceptions of specific groups but usually leaving them within the same cluster as their generic ethnicity (Fiske and Lee forthcoming). Unfortunately, factors under a group’s control, such as documentation, language, and generations of residence, do not trump ethnicity, although they help. These features, however, can mitigate antiimmigrant sentiment (whose default is negative, but some is ambivalent) as managers confront these issues.

Ageism

Another management challenge—a protected category like gender and race but also like immigration status, and a shifting one that people occupy differently throughout the life course—age is understudied as a basis of prejudice (North and Fiske n.d.-a). The default descriptive stereotype of older people, all over the world, is that they are warm but incompetent (Cuddy and Fiske 2002; Cuddy et al. 2009; Durante et al. n.d.). Even in rural China, older people are viewed as pitifully incompetent, though well intentioned (Chen and Fiske n.d.). The elder stereotype resists change (Cuddy, Norton, and Fiske 2005); attempts to make an older person seem more competent do not succeed well at changing competence, though they do inversely affect warmth ratings. This experimental vignette result fits the contact literature’s finding that young-old contact programs rarely work to improve ageist bias (North and Fiske n.d.-a).

One reason for the stickiness of the old-age stereotype may be its prescriptive as well as its descriptive nature. As noted, gender stereotypes are prescriptive because of men’s and women’s intimate interdependence. People not only have both genders in their families, but also many age categories, all of which are interdependent. This interdependence underlies intergenerational resentments over resources (North and Fiske n.d.-b), as follows.

Consider intergenerational relations as a movie-ticket line, with younger people at the back; ahead of them are middle-aged people, and older people stand at the front. If the older people take too long with the resources of the ticket-seller’s attention, those behind them become impatient. This resembles tensions over orderly succession for higher-status positions at work or for family wealth and possessions at home. In this case, the older people enjoy an enviable position, seen as high-status, though perhaps cold and unfeeling for actively rejecting the needs of those behind them. If the older people at the front of the line use up all the tickets (at a senior discount), other tensions may result over their unwarranted consumption of shared resources. These selfish older people are ignoring the needs of others, more passively in this case, so perhaps they are not so much enviable as contemptible in their exploitation of their turn. Finally, if the senior citizens are buying tickets to a seemingly age-inappropriate movie, the younger audience members may resent the invasion of their generational identity.

Moving beyond analogies, intergenerational tensions over resources, identity, and consumption do predict ageist prejudice uniquely targeting older people and uniquely held by younger people (North and Fiske n.d.-b). Each of these dimensions constitutes a component of ageist reactions to vignettes in which an older person either adheres to or violates ageist prescriptions regarding orderly succession, unfair consumption, and age-inappropriate identity. Each dimension also constitutes a piece of a reliable ageism scale.

From a management perspective, this suggests that patterns of ageism differ depending on the older person’s perceived response to ageist prescriptions. Just as nontraditional women incur a penalty for challenging the low-competence, highwarmth default roles for women, so do nontraditional elders forfeit the same cluster that entails sympathy and pity. Violating prescriptive stereotypes incurs costs on both perceived warmth and competence as well as on younger people’s willingness to interact with older people.

Classism

Although social class is not a protected category in the workplace, class divides are increasing in the United States, with ill effects on well-being (Wilkinson and Pickett 2009) that relate to work. Increased inequality decreases social mobility (Blanden, Gregg, and Machin 2005; Solon 2002), trust (Uslaner 2002; kawachi et al. 1997; Wilkinson and Pickett 2009), education (Wilkinson and Pickett 2009), happiness, and well-being (Alesina, Di Tella, and MacCulloch 2004). As noted earlier, societies with more inequality recruit SCM’s ambivalent clusters to a reliably greater degree, consistent with a system-justifying function of stereotypes (Durante et al. n.d.).

Social class divides manifest in daily interactions (Fiske 2011; Fiske and Markus forthcoming), undermining the feeling of fit when people from working-class backgrounds or identities navigate the resource-rich contexts of privilege in the professions, higher education, and even elementary school. Of course, sociologists have long considered social class (e.g., Lareau and Conley 2010), but a social psychological angle identifies the face-to-face mechanisms that sustain social class divides.

Starting with elementary school, working-class parents encounter the world of middle-class teachers with some differing assumptions that may undermine their advocacy for their children (Lareau and Calarco forthcoming). For example, middle-class parents often view education as growing their children, allowing them to blossom, whereas working-class parents view education as disciplining their unruly little animals, turning them into responsible adults (kusserow forth-coming). Working-class children’s collaborative storytelling styles (e.g., interdependent, call and response) do not fit middle-class educational settings, which are relentlessly individualistic (Miller and Sperry forthcoming).

As adults, individuals with a working-class background or identity encounter crucial gateway interactions: college and employment interviews, networking at school and at work, and daily workplace interactions; where middle-class models are more likely to succeed, providing access to the resources for social mobility (Ridgeway and Fisk forthcoming; Stephens, Fryberg, and Markus forthcoming). The cues are often subtle and unexamined nonverbal signals (kraus, Rheinschmidt, and Piff forthcoming) or unexamined affiliative and competence beliefs about different social class groups (Fiske et al. forthcoming). These signals and beliefs produce feelings of being a misfit and mistrust in cross-class interactions. Mistrust between those of different class backgrounds, fostered by institutional experiences and stereotyped beliefs, can foster inequality through everyday interactions.

How Does This Relate to Management?

In hiring, training, and promotion, first impressions shape subsequent impressions. Even as decision-makers gain additional information, the new information is anchored in the initial impressions, for better or worse (Fiske 1998; Macrae and Bodenhausen 2000). Individuating information—beyond the initial demographic categories of gender, sexuality, race, immigrant status, age, and class—does not eliminate the problem. For effective management of these prejudices, the take-away messages are as follows:

Not all prejudices are alike; they vary in perceived warmth and competence, creating predictable clusters of stereotypes, emotional prejudices, and discriminatory tendencies.

Managing a specific group’s dilemma should work to counteract its stereotypically weak dimension, for example, warmth for Asians, competence for older people.

Emotions drive behavior, and emotional prejudices are the proximal causes of discrimination.

Antecedents, indicators, and consequences of bias will differ by specific out-group.

Often these biases are subtle and unexamined, not the overt biases of the past century.

Organization-level management strategies suggest a focus on the antecedents (status and interdependence structures) that predict stereotypes and prejudices.

Societal levels of management suggest that growing income inequality (status divides) and political polarization (failures to cooperate) worsen these destructive dynamics.

Constructive contact between groups (involving cooperation, equal-status in the setting, important goals and authority sanctions) especially improves emotional prejudices (Pettigrew and Tropp 2006).

In addition to worrying about status divides that result from inequality, we also need to worry about affiliative divides that affect relational capital. Both warmth and competence determine success.

References

- Alesina Alberto, Tella Rafael Di, MacCulloch Robert. Inequality and happiness: Are Europeans and Americans different? Journal of Public Economics. 2004;88:2009–42. [Google Scholar]

- Barreto Manuela, Ellemers Naomi, Piebinga Laura, Moya Miguel. How nice of us and how dumb of me: The effect of exposure to benevolent sexism on women’s task and relational self-descriptions. Sex Roles. 2010;62(7-8):532–44. [Google Scholar]

- Benard Stephen, Paik In, Correll Shelley J. Cognitive bias and the motherhood penalty. Hastings Law Journal. 2008;59:1359–87. [Google Scholar]

- Berger Joseph, Cohen Bernard P., Zelditch Morris. Status characteristics and social interaction. American Sociological Review. 1972;37(3):241–55. [Google Scholar]

- Bergsieker Hilary B., Leslie Lisa M., Constantine Vanessa S., Fiske Susan T. Stereotyping by omission: Eliminate the negative, accentuate the positive. doi: 10.1037/a0027717. n.d. Manuscript under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanden Jo, Gregg Paul, Machin Stephen. Intergenerational mobility in Europe and North America. Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics; London: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bosson Jennifer k., Pinel Elizabeth C., Vandello Joseph A. The emotional impact of ambivalent sexism: Forecasts versus real experiences. Sex Roles. 2010;62(7-8):520–31. [Google Scholar]

- Budig Michelle J., England Paula. The wage penalty for motherhood. American Sociological Review. 2001;66(2):204–25. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess Diana, Borgida Eugene. Who women are, who women should be: Descriptive and prescriptive gender stereotyping in sex discrimination. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law. 1999;5(3):665–92. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Zhixia, and Susan T. Fiske. n.d. [Unpublished data].

- Cikara Mina, Farnsworth Rachel A., Harris Lasana T., Fiske Susan T. On the wrong side of the trolley track: Neural correlates of relative social valuation. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 2010;5:404–13. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsq011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clausell Eric, Fiske Susan T. When do the parts add up to the whole? Ambivalent stereotype content for gay male subgroups. Social Cognition. 2005;23:157–76. [Google Scholar]

- Correll Shelley J., Benard Stephen, Paik In. Getting a job: Is there a motherhood penalty? American Journal of Sociology. 2007;112:1297–1338. [Google Scholar]

- Cuddy Amy J. C., Fiske Susan T., Nelson Todd D. Ageism. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 2002. Doddering, but dear: Process, content, and function in stereotyping of older persons; pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Cuddy Amy J. C., Fiske Susan T., Glick Peter. When professionals become mothers, warmth doesn’t cut the ice. Journal of Social Issues. 2004;60:701–18. [Google Scholar]

- Cuddy Amy J. C., Fiske Susan T., Glick Peter. The BIAS map: Behaviors from intergroup affect and stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92:631–48. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.4.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuddy Amy J. C., Fiske Susan T., Glick Peter, Zanna Mark P. Advances in experimental social psychology. Academic Press; New York, NY: 2008. Competence and warmth as universal trait dimensions of interpersonal and intergroup perception: The Stereotype Content Model and the BIAS Map; pp. 61–149. [Google Scholar]

- Cuddy Amy J. C., Fiske Susan T., kwan Virginia S. Y., Glick Peter, Demoulin Stephanie, Leyens Jacques-Philippe, Bond Michael Harris, Croizet Jean-Claude, Ellemers Naomi, Sleebos Ed, et al. Stereotype content model across cultures: Towards universal similarities and some differences. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2009;48:1–33. doi: 10.1348/014466608X314935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuddy Amy J. C., Norton Michael I., Fiske Susan T. This old stereotype: The pervasiveness and persistence of the elderly stereotype. Journal of Social Issues. 2005;61:265–83. [Google Scholar]

- Dardenne Benoit, Dumont Muriel, Bollier Thierry. Insidious dangers of benevolent sexism: Consequences for women’s performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;93(5):764–79. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.5.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio John F., Gaertner Samuel L., Zanna Mark P. Advances in experimental social psychology. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2004. Aversive racism; pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio John F., kawakami kerry, Gaertner Samuel L. Implicit and explicit prejudice and interracial interaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82(1):62–68. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.82.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont Muriel, Sarlet Marie, Dardenne Benoit. Be too kind to a woman, she’ll feel incompetent: Benevolent sexism shifts self-construal and autobiographical memories toward incompetence. Sex Roles. 2010;62(7-8):545–53. [Google Scholar]

- Durante Federica, Fiske Susan T., kervyn Nicolas, Cuddy Amy J. C., Akande Adebowale (Debo), Barlow Fiona kate, Bosak Janine, Cairns Ed, Doherty Claire, Capozza Dora, et al. Nations’ income inequality predicts ambivalence in stereotype content: How societies mind the gap. n.d. Manuscript under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durante Federica, Volpato Chiara, Fiske Susan T. Using the Stereotype Content Model to examine group depictions in fascism: An archival approach. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2009;39:1–19. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagly Alice H. Sex differences in social behavior: A social-role interpretation. Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Eagly Alice H., karau Steven J. Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review. 2002;109:573–98. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.109.3.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagly Alice H., Mladinic Antonio, Otto Stacey. Are women evaluated more favorably than men? An analysis of attitudes, beliefs, and emotions. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 1991;15(2):203–16. [Google Scholar]

- Eckes Thomas. Paternalistic and envious gender stereotypes: Testing predictions from the stereo-type content model. Sex Roles. 2002;47(3-4):99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Fields Alice M., Swan Suzanne, kloos Bret. “What it means to be a woman”: Ambivalent sexism in female college students’ experiences and attitudes. Sex Roles. 2010;62(7-8):554–67. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske Susan T. Stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination. In: Gilbert Daniel T., Fiske Susan T., Lindzey Gardner., editors. Handbook of social psychology. 4th ed. McGraw-Hill; New York, NY: 1998. pp. 357–411. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske Susan T. Envy up, scorn down: How status divides us. Russell Sage Foundation; New York, NY: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske Susan T., Bergsieker Hilary, Russell Ann-Marie, Williams Lyle. Images of black Americans: Then, “them” and now, “Obama!”. DuBois Review: Social Science Research on Race. 2009;6:83–101. doi: 10.1017/S1742058X0909002X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske Susan T., Cuddy Amy J. C., Glick Peter. Universal dimensions of social perception: Warmth and competence. Trends in Cognitive Science. 2007;11:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske Susan T., Cuddy Amy J. C., Glick Peter, Xu Jun. A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82:878–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske Susan T., Lee Tiane L. Forthcoming. Xenophobia and how to fight it: Immigrants as the quintessential “other”. In: Wiley Shaun, Revenson Tracey, Philogene Gina., editors. Social categories in everyday experience. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: [Google Scholar]

- Fiske Susan T., Markus Hazel Rose. Facing social class: Social psychology of social class. Russell Sage Foundation; New York, NY: Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske Susan T., Moya Miguel, Russell Ann Marie, Bearns Courtney. The secret hand-shake: Trust in cross-class encounters. In: Fiske Susan T., Markus Hazel Rose., editors. Facing social class: Social psychology of social class. Russell Sage Foundation; New York, NY: Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske Susan T., Stevens Laura E., Oskamp Stuart, Costanzo Mark. Gender issues in contemporary society: Applied social psychology annual. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1993. What’s so special about sex? Gender stereotyping and discrimination; pp. 173–96. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert Daniel T., Silvera David H. Overhelping. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70(4):678–90. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.4.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick Peter, Diebold Jeffrey, Bailey-Werner Barbara, Zhu Lin. The two faces of Adam: Ambivalent sexism and polarized attitudes toward women. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1997;23(12):1323–34. [Google Scholar]

- Peter Glick, Fiske Susan T. The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70:491–512. [Google Scholar]

- Glick Peter, Fiske Susan T., Ann Ropp S. Sex discrimination: The psychological approach. In: Crosby Faye J., Stockdale Margaret S., editors. Sex discrimination in the workplace: Multidisciplinary approaches. Blackwell; Malden, MA: 2007. pp. 155–88. [Google Scholar]

- Glick Peter, Fiske Susan T., Mladinic Antonio, Saiz José L., Abrams Dominic, Masser Barbara, Adetoun Bolanle, Osagie Johnstone E., Akande Adebowale, Alao Amos, et al. Beyond prejudice as simple antipathy: Hostile and benevolent sexism across cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:763–75. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.5.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris Lasana T., Fiske Susan T. Dehumanizing the lowest of the low: Neuro-imaging responses to extreme outgroups. Psychological Science. 2006;17:847–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty Peter, Pratto Felicia. Sexual orientation beliefs: Their relationship to anti-gay attitudes and biological determinist arguments. Journal of Homosexuality. 2001;41(1):121–35. doi: 10.1300/J082v41n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilman Madeline E. Description and prescription: How gender stereotypes prevent women’s ascent up the organizational ladder. Journal of Social Issues. 2001;57(4):657–74. [Google Scholar]

- Herek Gregory M. The psychology of sexual prejudice. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2000;9(1):19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Hoobler Jenny M., Wayne Sandy A., Lemmon Grace. Bosses’ perceptions of family-work conflict and women’s promotability: Glass ceiling effects. Academy of Management Journal. 2009;52(5):939–57. [Google Scholar]

- katz Irwin, Glen Hass R. Racial ambivalence and American value conflict: Correlational and priming studies of dual cognitive structures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;55:893–905. [Google Scholar]

- kawachi Ichiro, kennedy Bruce P., Lochner kimberly, Deborah Prothrow-Stith. Social capital, income inequality, and mortality. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87:1491–98. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.9.1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- kervyn Nicolas, Fiske Susan T. The Stereotype Content Model and Osgood’s Semantic Differential: Reconciling warmth and competence with evaluation, potency, and activity. n.d. Manuscript under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- kervyn Nicolas, Fiske Susan T., Yzerbyt Vincent. Mapping social perception: Testing the stereotype content model with a multidimensional approach. n.d.-a. Manuscript under review. [Google Scholar]

- kervyn Nicolas, Fiske Susan T., Yzerbyt Vincent. Why is the primary dimension of social cognition so hard to predict? Symbolic and realistic threats together predict warmth in the stereotype content model. n.d.-b. Manuscript under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- kervyn Nicolas, Yzerbyt Vincent Y., Judd Charles M., Nunes Ana. A question of compensation: The social life of the fundamental dimensions of social perception. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;96(4):828–42. doi: 10.1037/a0013320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- kraus Michael W., Rheinschmidt Michelle L., Piff Paul k. The intersection of resources and rank: Signaling social class in face-to-face encounters. In: Fiske Susan T., Markus Hazel Rose., editors. Facing social class: Social psychology of social class. Russell Sage Foundation; New York, NY: Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- kusserow Adrie. Forthcoming. When hard and soft clash: Class-based individualisms in Manhattan and Queens. In: Fiske Susan T., Markus Hazel Rose., editors. Facing social class: Social psychology of social class. Russell Sage Foundation; New York, NY: [Google Scholar]

- Lareau Annette, Calarco Jessica McCrory. Class, cultural capital, and institutions: The case of families and schools. In: Fiske Susan T., Markus Hazel Rose., editors. Facing social class: Social psychology of social class. Russell Sage Foundation; New York, NY: Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Lareau Annette, Conley Dalton. Social class: How does it work? Russell Sage Foundation; New York, NY: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Tiane L., Fiske Susan T. Not an out-group, but not yet an in-group: Immigrants in the stereotype content model. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 2006;30:751–68. [Google Scholar]

- Macrae C. Neil, Bodenhausen Galen V. Social cognition: Thinking categorically about others. Annual Review of Psychology. 2000;51:93–120. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller Peggy J., Sperry Douglas E. Déjà vu: Contesting language deficiency again. In: Fiske Susan T., Markus Hazel Rose., editors. Facing social class: Social psychology of social class. Russell Sage Foundation; New York, NY: Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- North Michael S., Fiske Susan T. An inconvenienced youth: Ageism as intergenerational tensions over resources. n.d.-a. Manuscript under review. [Google Scholar]

- North Michael S., Fiske Susan T. The young and the ageist: Intergenerational tensions over succession, identity, and consumption. n.d.-b. Manuscript under review. [Google Scholar]

- Osgood Charles E., Suci George J., Tannenbaum Percy H. The measurement of meaning. University of Illinois Press; Urbana: 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Peeters Guido. In search for a social-behavioral approach-avoidance dimension associated with evaluative trait meanings. Psychologica Belgica. 2001;41(4):187–203. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew Thomas F., Tropp Linda R. A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;90(5):751–83. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan Julie E., Moss-Racusin Corinne A., Rudman Laurie A. Competent yet out in the cold: Shifting criteria for hiring reflect backlash toward agentic women. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2008;32(4):406–13. [Google Scholar]

- Podolny Joel M., Baron James N. Resources and relationships: Social networks and mobility in the workplace. American Sociological Review. 1997;62(5):673–93. [Google Scholar]

- Ridgeway Cecilia L. The social construction of status value: Gender and other nominal characteristics. Social Forces. 1991;70(2):367–86. [Google Scholar]

- Ridgeway Cecilia L., Fiske Susan T. Class rules, status dynamics, and “gateway” interactions. In: Fiske Susan T., Markus Hazel Rose., editors. Facing social class: Social psychology of social class. Russell Sage Foundation; New York, NY: Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg Seymour, Nelson Carnot, Vivekananthan PS. A multidimensional approach to the structure of personality impressions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1968;9(4):283–94. doi: 10.1037/h0026086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudman Laurie A., Glick Peter. Prescriptive gender stereotypes and backlash toward agentic women. Journal of Social Issues. 2001;57(4):743–62. [Google Scholar]

- Rudman Laurie A., Phelan Julie E. Backlash effects for disconfirming gender stereotypes in organizations. In: Brief Arthur P., Staw Barry M., editors. Research in organizational behavior. Elsevier; New York, NY: 2008. pp. 61–79. [Google Scholar]

- Shelton J. Nicole. Interpersonal concerns in social encounters between majority and minority group members. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations. 2003;6(2):171–85. [Google Scholar]

- Shelton J. Nicole, Richeson Jennifer A. Interracial interactions: A relational approach. In: Zanna Mark P., editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 2006. pp. 121–81. [Google Scholar]

- Sherif Muzafer, Sherif Carolyn W. Groups in harmony and tension: An integration of studies of intergroup relations. Harper; Oxford: 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Solon Gary. Cross-country differences in intergenerational earnings mobility. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2002;16:59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Spence Janet T., Helmreich Robert. Who likes competent women? Competence, sex role congruence of interests, and subjects’ attitudes toward women as determinants of interpersonal attraction. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1972;2(3):197–213. [Google Scholar]

- Spence Janet T., Helmreich Robert, Stapp Joy. A short version of the Attitudes toward Women Scale (AWS) Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society. 1973;2(4):219–20. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens Nicole M., Fryberg Stephanie A., Markus Hazel Rose. It’s your choice: How the middle class model of independence disadvantages working class Americans. In: Fiske Susan T., Markus Hazel Rose., editors. Facing social class: Social psychology of social class. Russell Sage Foundation; New York, NY: Forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel Henri. Human groups and social categories. Cambridge University Press; New York, NY: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Uslaner Eric M. The moral foundations of trust. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson Richard G., Pickett kate E. Income inequality and social dysfunction. Annual Review of Sociology. 2009;35:493–511. [Google Scholar]

- Wojciszke Bogdan, Abele Andrea E., Baryla Wieslaw. Two dimensions of interpersonal attitudes: Liking depends on communion, respect depends on agency. European Journal of Social Psychology. 2009;39(6):973–90. [Google Scholar]