Abstract

Background

The relevance of allergic sensitization, as judged by titers of serum IgE antibodies, to the risk of an asthma exacerbation caused by rhinovirus is unclear.

Objective

We sought to examine the prevalence of rhinovirus infections in relation to the atopic status of children treated for wheezing in Costa Rica, a country with an increased asthma burden.

Methods

The children enrolled (n = 287) were 7 through 12 years old. They included 96 with acute wheezing, 65 with stable asthma, and 126 nonasthmatic control subjects. PCR methods, including gene sequencing to identify rhinovirus strains, were used to identify viral pathogens in nasal washes. Results were examined in relation to wheezing, IgE, allergen-specific IgE antibody, and fraction of exhaled nitric oxide levels.

Results

Sixty-four percent of wheezing children compared with 13% of children with stable asthma and 13% of nonasthmatic control subjects had positive test results for rhinovirus (P < .001 for both comparisons). Among wheezing subjects, 75% of the rhinoviruses detected were group C strains. High titers of IgE antibodies to dust mite allergen (especially Dermatophagoides species) were common and correlated significantly with total IgE and fraction of exhaled nitric oxide levels. The greatest risk for wheezing was observed among children with titers of IgE antibodies to dust mite of 17.5 IU/mL or greater who tested positive for rhinovirus (odds ratio for wheezing, 31.5; 95% CI, 8.3-108; P < .001).

Conclusions

High titers of IgE antibody to dust mite allergen were common and significantly increased the risk for acute wheezing provoked by rhinovirus among asthmatic children.

Key words: Acute asthma, dust mite–specific IgE, emergency department visits, viral respiratory tract infections, rhinovirus strain C, total serum IgE, inhaled allergens, exhaled nitric oxide

Abbreviations used: ED, Emergency department; ETS, Environmental tobacco smoke; Feno, Fraction of exhaled nitric oxide; GM, Geometric mean; ICAM-1, Intercellular adhesion molecule 1; RSV, Respiratory syncytial virus

In countries with temperate climates (eg, North America, Europe, and Australia), viral respiratory tract infections are associated with 80% to 90% of wheezing attacks in the pediatric population, especially during early childhood.1, 2, 3, 4 After 3 years of age, rhinovirus accounts for 75% to 80% of the virus-induced attacks leading to hospitalizations and emergency department (ED) visits, and the majority of these children are atopic.1, 5 Evidence to date also indicates that a rhinovirus infection together with sensitization and exposure to inhaled allergens increases the risk for acute symptoms, suggesting that these risk factors might act synergistically to provoke asthma exacerbations.1, 5, 6 Whether these observations can be generalized to children living in countries with tropical climates is not clear. In studies from Brazil and Trinidad, the prevalence of infections with rhinovirus among children treated for asthma was less than half of what has been reported in countries with temperate climates.7, 8 Recognizing that additional studies are needed from tropical environments to gain a better understanding of the role of viral infections in the cause of asthma exacerbations worldwide, the purpose of this investigation was to examine the prevalence of viral respiratory tract infections among children treated for acute wheezing in Costa Rica and to evaluate the results in relation to their atopic status.

Costa Rica is a small country (19,730 square miles) in Central America with a diverse ecosystem. Similar to other countries near the equator, Costa Rica has 2 seasons: a “dry” season (generally December through April) and a “rainy” season (May through November). Exposure to Helminthes, which, like environmental allergens, can stimulate the production of IgE, is common in economically deprived regions of Hispanic America. However, anti-helminth medications are given annually to children in Costa Rica starting at 1 year of age. Thus active parasitic and enteric infections during childhood are not frequent in that country (eg, ≤2% for infections with Ascaris lumbricoides).9, 10

According to school surveys and studies using the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood questionnaire, the prevalence of asthma among school-aged children in Costa Rica (approximately 23% to 27%) is higher than in North America,11, 12 and sensitization to allergens, especially to allergens produced by house dust mites, is common.13 At present, however, there is little information about the relevance of viral infections to acute attacks of asthma in this country. Additionally, recent evidence from countries with temperate climates suggest that group C strains of rhinovirus might be strongly related to asthma exacerbations compared with other strains.14, 15, 16 This information is also lacking in studies of asthma in tropical countries. Thus our objective was to investigate the relationship between respiratory tract viruses, including different strains of rhinovirus, and episodes of asthma requiring acute treatment. Additionally, we took advantage of the dominance of dust mite sensitization in Costa Rica to investigate the relationship of titers of IgE antibodies to exacerbations of asthma with or without evidence of a recent viral infection.

Methods

Study population

This was a cross-sectional case-control investigation of 287 children aged 7 to 12 years enrolled in the ED of the Hospital Nacional de Niños, the main tertiary care hospital for children in San José, Costa Rica, where the majority of children are seen for trauma, wheezing illnesses, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and fever. Subjects included 96 children referred to the acute care nebulization room for wheezing by a triage physician. They required at least a nebulized bronchodilator (albuterol) for treatment. Children seen in the ED for nonwheezing disorders (n = 191) were enrolled as control subjects. They included 65 children who had been hospitalized or treated in the ED or who had been using medications prescribed by a physician for asthma during the last 12 months. Data from the latter group, who were defined as having “stable asthma” at the time of enrollment, were compared with data obtained from the actively wheezing children and other nonwheezing control subjects in a post hoc analysis. Children with chronic lung disease, congenital heart disease, or immunodeficiency or oncologic disorders were not enrolled.

The subjects included 137 children (44 with wheezing) enrolled in February 2009 during the dry season, when children in Costa Rica begin the school year, and 150 children (51 with wheezing) enrolled in October 2009 during the rainy season, 1 month before the end of the school year. Demographic information and subjects' characteristics were obtained from questionnaires administered to parents. The questionnaires focused on each child's history for asthma treatments, family history for allergic disorders, and environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) exposure at home. Informed consent was obtained from parents, and informed assent was obtained from children who participated. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee at the Hospital Nacional de Niños and by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Virginia.

Virus detection

Nasal washes were obtained for viral analyses, as described in the Methods section in this article's Online Repository at www.jacionline.org. Initially, they were evaluated for rhinovirus by using RT-PCR, as described previously.17, 18 Other respiratory viral pathogens were evaluated by using real-time PCR assays obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, according to published procedures.19, 20 These assays included tests for rhinovirus, as well as tests for influenza A (including H1N1) and B; respiratory syncytial virus (RSV); human metapneumovirus; parainfluenza viruses 1, 2, and 3; coronaviruses (229E, OC43, NL63, and HKU1 species); and adenovirus. A high degree of concordance was observed between RT-PCR and real-time PCR methods for detecting rhinovirus (percentage of absolute agreement, 93.3%; 95% CI, 89.8% to 95.9%). Additionally, strains of rhinovirus and enterovirus were identified by means of PCR and sequencing of a region comprising the VP4 and partial VP2 capsid protein genes.21, 22

Measurements of total serum IgE, allergen-specific IgE antibody, and fraction of exhaled nitric oxide levels

Blood (5 mL) was obtained by means of venipuncture, and serum from each sample was analyzed for the total IgE level by using the Phadia ImmunoCAP assay (Phadia, Uppsala, Sweden). Each sample was also analyzed for allergen-specific IgE antibody to dust mite (Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus, Dermatophagoides farinae, and Blomia tropicalis), Alternaria species, Aspergillus species, cockroach (Periplaneta americana and Blattella germanica), Bahia grass, cat and dog allergens, and A lumbricoides. Sera with 0.35 IU/mL or greater IgE antibody to any of the allergens tested were considered positive for allergen sensitization. Fraction of exhaled nitric oxide (Feno) levels were measured with a portable Feno analyzer (NIOX MINO; Aerocrine, Inc, New Providence, NJ).

Statistical analysis

Questionnaire data and frequencies for positive test results for viral pathogens and allergen sensitization were analyzed by using robust exact binomial and exact multinomial contingency table methods. Binomial contingency table hypotheses were evaluated by using the exact binomial test, whereas multinomial contingency table hypotheses were evaluated by using the Pearson exact goodness-of-fit test. For both the binomial and multinomial contingency table analyses, the 2-sided null hypothesis rejection rule was set at a P value of .05 or less. Multivariate logistic regression was used to determine whether a child's wheezing status was associated with rhinovirus infection and atopic status. Tests of association were based on the type III Wald χ2 statistic, and a P value of .05 or less was used to identify significant associations. Total serum IgE levels, titers of allergen-specific IgE antibody, and Feno levels were analyzed on a logarithmic scale by using 2-way ANOVA. The 2 sources of variation considered in the ANOVA were the study group and the season of data collection. The rejection rule for hypothesis testing was based on a P value of .05 or less, and 95% CI construction for the ratio of the geometric means (GMs) was based on the Student t test distribution. The statistical software package SAS version 9.2.2 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC) was used to conduct statistical analyses.

Results

Demographics and subjects' characteristics

Among the control children enrolled who presented to the ED with a diagnosis that did not involve breathlessness, 34% (65/191) had stable asthma, as judged by parental report of treatment regimens. The percentages of the 96 wheezing children and those with stable asthma who had required hospitalization or treatment in the ED or who used medications (bronchodilator, controller, or both) for asthma during the last 12 months were similar (Table I ). A minority of children in this study were exposed to ETS at home (23%), more often from the father. Children with stable asthma had less exposure to ETS at home, and they used inhaled and nasal steroids daily more often than children enrolled for wheezing (Table I). More detailed comparisons for children enrolled in February and October are shown in Table E1 in this article's Online Repository at www.jacionline.org.

Table I.

Demographics and subjects' characteristics (February and October enrollments combined)

| Children with current wheeze (n = 96) | Children with stable asthma (n = 65) | Control subjects (n = 126) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (y) | 8.8 | 9.1 | 9.4 |

| Sex (% male) | 58% | 58% | 47% |

| ED treatment for asthma, last 12 mo | 90% | 85% | NA |

| Hospitalization for asthma, last 12 mo | 10.5% | 15.4% | NA |

| Asthma medication use | |||

| Last 12 mo | 78% | 83% | NA |

| Last month | 60% | 51% | NA |

| Percent with daily use of: | |||

| Inhaled steroids | 36% | 54% | NA |

| Nasal steroids | 5%¶ | 26% | NA |

| Montelukast | 13% | 14% | NA |

| >10 d of school missed for asthma | 26% | 32% | NA |

| Worst season (% dry/rainy/not seasonal)∗ | 4%/59%/37% | 2%/66%/33% | NA |

| Family history of asthma | |||

| Mother† | 30%‖ | 31%§§ | 10% |

| Father | 17%‖ | 18%‡‡ | 4% |

| ETS exposure | 26%¶ | 11% | 27%‡‡ |

| ETS exposure from mother | 4% | 5% | 6% |

| ETS exposure from father | 13% | 3% | 18%†† |

NA, Not applicable.

Symbols marking significant differences between groups include the following: wheezing children versus nonasthmatic control subjects (‡P < .05, §P < .01, and ‖P < .001); wheezing children versus children with stable asthma (¶P < .05, #P < .01, and **P < .001); and children with stable asthma versus nonasthmatic control subjects (††P < .05, ‡‡P < .01, and §§P < .001). More details are shown in Table E1.

Percentage of parents reporting that their child's asthma was worse during the rainy or dry season or that their symptoms were not seasonal. Both wheezing children and those with stable asthma had symptoms that were worse during the rainy than the dry season (P < .001) or compared with children whose symptoms were not seasonal (P < .05).

For children with wheezing and those with stable asthma, the maternal history for asthma was significantly higher than the paternal history for asthma (P < .05).

Virus identification

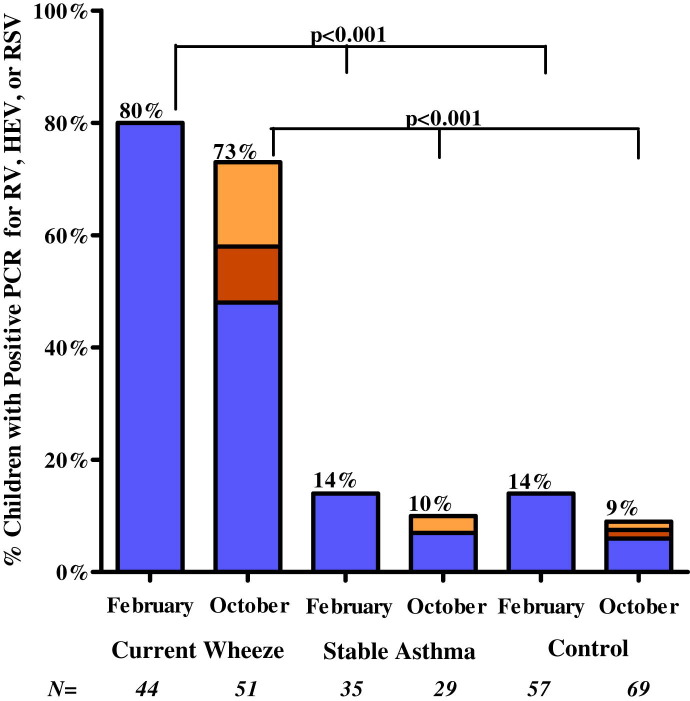

The percentage of children with positive test results for any virus was significantly greater among wheezing children than among those with stable asthma or nonasthmatic control subjects (Table II ). The percentages were similar among wheezing children during both enrollment periods (84% in February and 83% in October). The percentage of those with positive test responses for rhinovirus was also significantly greater among the wheezing children during both enrollment periods but greater among wheezing children enrolled in February (80% [35/44]) than in October (48% [25/51], P < .029, Fig 1 ). Based on real-time PCR results, rhinovirus accounted for 74% of the viral pathogens detected (Table II). RSV and enterovirus (predominantly strain 68) were the only other pathogens significantly associated with wheezing (10.4% and 6.3%, respectively), and these 2 viral pathogens were only detected in washes from children who were enrolled in October (Fig 1 and Table II).

Table II.

Percentage of children with positive test results for common respiratory tract pathogens by means of real-time PCR∗

| Children with current wheeze (n = 96) | Children with stable asthma (n = 64) | Control subjects (n = 126) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any virus | 83% (80)§ | 17% (11) | 21% (27) |

| Rhinovirus, all groups | 64% (61)§ | 13% (8) | 13% (17) |

| Group C¶ | 75% (46)§ | 50% (4) | 35% (6) |

| Group A¶ | 25% (15)‡ | 25% (2) | 47% (8) |

| Group B¶ | 1% (1)‖ | 25% (2) | 18% (3) |

| RSV | 10.4% (10)‡ | 0% (0) | 1% (1) |

| Metapneumovirus | 2.0% (2) | 3.1% (2) | 1% (1) |

| Parainfluenza virus (1, 2, and 3) | 2.0% (2) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) |

| Adenovirus | 2.0% (2) | 0% (0) | 1.6% (2) |

| Coronavirus# | 2.0% (2) | 1.6% (1) | 4.0% (5) |

| Influenza A and B∗∗ | 2.0% (2) | 0% (0) | 1% (1) |

| Enterovirus†† | 6.3% (6)† | 1.6% (1) | 1% (1) |

The percentage of children with positive test results for each virus is shown in the table, followed by the number of children with positive test results in parentheses. Significant differences between wheezing versus nonwheezing children (children with stable asthma and nonasthmatic subjects combined) are indicated as follows: †P < .05, ‡P < .01, and §P < .001.

This subject had positive test results for both group A and B strains.

Percentage of children with positive test results for rhinovirus with positive test results for group C, A, or B strains.

Results for coronavirus include positive test results for 229E, NL63, OC43, and HKU1 species.

One wheezing subject and 1 nonasthmatic control subject enrolled in October had a positive test result for 2009 H1N1. One wheezing subject had a positive test result for influenza B and for RSV.

Six of the 8 positive test results for enterovirus were positive for strain 68, which was previously reported to induce attacks of asthma in children.22

Fig 1.

Percentage of children with positive test results by using real-time PCR for rhinovirus (RV; blue columns), enterovirus (HEV; orange columns), or RSV (yellow columns), each of which was significantly associated with wheezing, as noted in Table III. Data are shown for children enrolled in February during the dry season and October during the rainy season. Of the 3 viruses, only rhinovirus was present in nasal secretions from subjects in February. P = .029 for the comparison of positive test results for rhinovirus (80% [35/44]) in February versus October (48% [25/51]).

Gene sequencing revealed that 75% of the nasal washes with positive test results for rhinovirus from wheezing children were positive for group C strains and 25% were positive for group A strains (Table II). The percentage of rhinoviruses identified as group C was similar among wheezing children enrolled in February and October (71% and 82%, respectively; P = .35). Four of the 8 patients with stable asthma with positive test results for rhinovirus also had positive test results for the group C strain. By comparison, 6 and 8 of the 17 rhinoviruses detected in washes from nonasthmatic control subjects were group C and A strains, respectively (P = .79). Only 6 children had positive test results for group B strains, 1 of whom was enrolled for wheezing. Additional information about the rhinovirus strains detected is shown in Table E2 in this article's Online Repository at www.jacionline.org.

Assessments of total IgE and allergen-specific IgE antibody levels

The GMs for total IgE in sera from wheezing children (482 IU/mL; 95% CI, 363-640 IU/mL) and patients with stable asthma (332 IU/mL; 95% CI, 235-469 IU/mL) were not significantly different (P = .10), but both values were higher than the total IgE levels from the nonasthmatic control subjects (86 IU/mL; 95% CI, 67-111 IU/mL; P < .001). Ninety-six percent of the wheezing children, 84% of the children with stable asthma, and 54% of the nonasthmatic control subjects had at least 1 positive test result for IgE antibodies to any allergen tested (P < .001 for patients with wheezing or stable asthma compared with control subjects; P < .05 for patients with wheezing compared with those with stable asthma; Table III ). The most frequent IgE antibody responses were to dust mite allergens (ie, D pteronyssinus, D farinae, or B tropicalis), and a strong correlation was observed between positive test results for IgE antibodies to D pteronyssinus and D farinae (r s = 0.95; 95% CI, 0.94-0.96; P < .001). Among the wheezing and stable asthma groups, both the prevalence of sensitization and the GMs of IgE antibody titers to allergens from each of the mite species were significantly greater compared with results from the nonasthmatic control subjects (P < .001, Table III). In addition, when adjusted for sensitization to the other allergens, dust mite was the only allergen sensitization that remained significantly associated with asthma (adjusted odds ratio, 4.9 [95% CI, 2.1-11.6] for IgE to B tropicalis and 2.7 [95% CI, 1.2-6.4] for IgE to D pteronyssinus).

Table III.

Assessments of allergen-specific IgE antibody levels (February and October enrollments combined)

| Children with current wheeze (n = 95) |

Children with stable asthma (n = 65) |

Control subjects (n = 123) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Positive‡‡ | IgE antibody titers§§ | % Positive‡‡ | IgE antibody titers§§ | % Positive‡‡ | IgE antibody titers§§ | |

| IgE antibody (IU/mL) to: | ||||||

| Any allergen | 96‡§ | NA | 84†† | NA | 54 | NA |

| Dust mite | ||||||

| D pteronyssinus | 90‡ | 25 (16-39)‡§ | 78†† | 11 (6-18)†† | 40 | 1.2 (0.8-1.8) |

| D farinae | 93‡§ | 18 (12-27)‡§ | 78†† | 8 (5-12)†† | 39 | 1.1 (0.8-1.5) |

| B tropicalis | 90‡ | 12 (8-18)‡ | 81†† | 8 (5-12)†† | 40 | 1.0 (0.7-1.4) |

| Other allergens | ||||||

| B germanica | 53‡ | 1.8 | 41** | 3.2# | 24 | 1.6 |

| P americana | 38‡ | 1.4 | 33†† | 1.7 | 11 | 1.3 |

| A lumbricoides | 42‡ | 0.7 | 36** | 0.7 | 18 | 0.4 |

| Alternaria species | 4* | 2.4 | 3 | ND | 0 | ND |

| Aspergillus species | 12† | 0.9 | 10# | 0.6 | 2 | 1.2 |

| Dog dander | 25‡ | 1.3 | 18** | 1.1 | 6 | 1.3 |

| Cat dander | 16 | 1.8 | 15 | 2.9 | 8 | 2.1 |

| Bahia grass | 11 | 1.4 | 13 | 4.8 | 7 | 1.7 |

NA, Not applicable; ND, not determined.

Symbols marking significant differences between groups include the following: children with wheezing versus nonasthmatic control subjects (*P < .05, †P < .01, and ‡P < .001); children with wheezing versus those with stable asthma (§P < .05, P < .01, and P < .001); and children with stable asthma versus nonasthmatic control subjects (#P < .05, **P < .01, and ††P < .001).

Percentage of children with IgE antibody levels of 0.35 IU/mL or greater to each allergen.

IgE antibody titers are shown as GMs. GMs are followed by 95% CIs in parentheses for the dust mite species. GMs for other allergens include only children whose allergen-specific IgE levels were 0.35 IU/mL or greater.

Sensitization to the cockroach species B germanica and P americana and to the helminth A lumbricoides was also greater among the wheezing children and those with stable asthma compared with that seen in the nonasthmatic control subjects (Table III). However, the prevalence of sensitization and titers of IgE antibodies (GMs) to these allergens were much lower than values for any of the dust mite species. Additionally, a strong correlation was observed between total serum IgE levels and the titers of IgE antibodies to D farinae, D pteronyssinus, or B tropicalis among asthmatic subjects (wheezing and stable asthmatic children combined: r = 0.72, 0.75, and 0.69, respectively; each P < .001). Data on other allergens and for IgE values in February and October are shown in Table E3 in this article's Online Repository at www.jacionline.org.

Odds ratio for wheezing based on titers of IgE antibodies and positive tests for rhinovirus

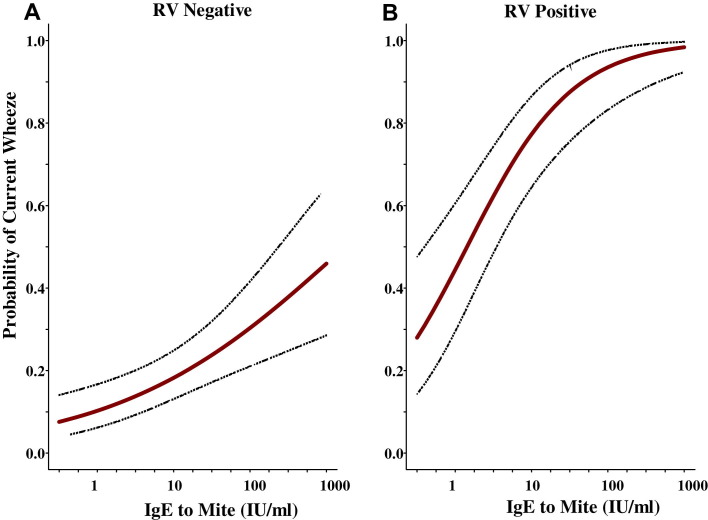

After adjusting for other viral pathogens and specific IgE antibodies, the main pathogenic factor that remained significantly associated with wheezing among the children enrolled was a positive test for rhinovirus (adjusted odds ratio, 14.3; 95% CI, 5.6-36.4; P < .001). The odds for wheezing, however, were strongly influenced by the titer of IgE antibodies to dust mite allergen. Among 45 children with titers of IgE antibodies to D pteronyssinus of 17.5 IU/mL or greater and a positive PCR test result for rhinovirus, 42 (93%) children required treatment for acute wheezing (odds ratio, 31.5; 95% CI, 8.3-108) compared with 16 (70%) of 23 children with titers of IgE antibodies between 0.35 and 17.4 IU/mL (odds ratio, 12.3; 95% CI, 3.8-39; Table IV ). Moreover, the probability of being enrolled for acute wheezing based on logistic regression analyses was significantly associated with increasing titers of IgE antibodies to D pteronyssinus (Fig 2 , A), and this risk was substantially higher among those with positive test results for rhinovirus (Fig 2, B). The relationship between IgE antibody titers and group C rhinovirus strains was the same as that for group A rhinovirus (Table IV). In addition, despite smaller numbers, the other 2 viruses associated with wheezing (RSV and enterovirus) show the same trend (see Table E4 in this article's Online Repository at www.jacionline.org).

Table IV.

Odds ratio for wheezing based on positive test results for rhinovirus and titers of IgE antibodies (in international units per milliliter) to dust mite (D pteronyssinus)

| Titer of IgE antibodies to mite: |

<0.35 IU/mL |

0.35-17.4 IU/mL |

≥17.5 IU/mL |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | PCR negative | PCR positive (A/C)∗ | PCR negative | PCR positive (A/C)∗ | PCR negative | PCR positive (A/C)∗ | |

| Wheezing children | 95 | 5 | 4† (2/2) | 8 | 16 (3/10) | 20 | 42 (8/30) |

| Nonwheezing children‡ | 186 | 73 | 15 (6/5) | 43 | 7 (2/3) | 45 | 3 (1/2) |

| Stable asthma | 63 | 13 | 2 (0/1) | 12 | 5 (1/2) | 31 | 1 (0/1) |

| Control | 123 | 60 | 13 (6/4) | 31 | 2 (1/1) | 14 | 2 (1/1) |

| Odds ratio§ | 3.89 (0.9-16), P = .07 | 12.3 (3.8-39), P < .001 | 31.5 (8.3-108), P < .001 | ||||

The number in parentheses indicates the number of subjects with positive test results for group A and group C strains of rhinovirus.

Two of these 4 children had IgE antibody to B tropicalis: 24.3 and 1.66 IU/mL.

Children with stable asthma combined with nonasthmatic control subjects.

Odds ratio for wheezing among rhinovirus-positive (real-time PCR) compared with rhinovirus-negative subjects.

Fig 2.

Probability of current wheezing based on increasing titers of IgE antibodies to D pteronyssinus in children with negative test results for rhinovirus by using real-time PCR (A) compared with children with positive test results for rhinovirus (B).

Rhinovirus, IgE antibodies, and Feno levels

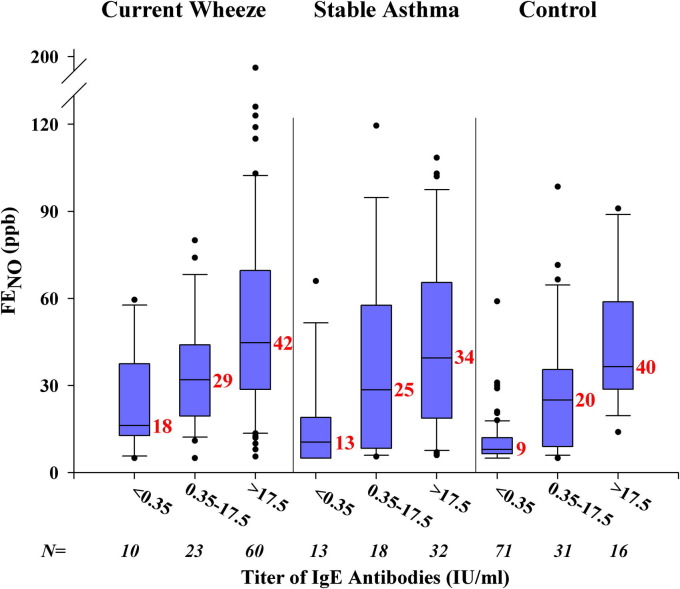

Feno levels (GMs) were significantly higher among wheezing children (35 ppb; 95% CI, 29-41 ppb) and those with stable asthma (25 ppb; 95% CI, 21-31 ppb) compared with levels among nonasthmatic control subjects (14 ppb; 95% CI, 12-16 ppb; P < .001 for both comparisons and P < .05 for wheezing compared with children with stable asthma). Feno levels were also higher among those with positive test results compared with those seen in subjects with negative test results for rhinovirus (40 compared with 28 ppb, P = .038) but were similar among those with positive test results for group C and group A strains (42 vs 36 ppb, respectively; P = .52). A positive correlation was observed between Feno levels and titers of IgE antibodies to mite in sera from children within each enrollment group (Fig 3 ). By contrast, Feno levels were not associated with sensitization to the cockroach species or Ascaris species.

Fig 3.

Relationship between measurements of Feno levels (in parts per billion) and increasing titers of IgE antibodies to D pteronyssinus. Results are shown for children with titers of IgE antibodies of 0.35 IU/mL or less, 0.35 to 17.4 IU/mL, and 17.5 IU/mL or greater. GM values for Feno for each group are shown in red.

Discussion

Infections with rhinovirus, most often group C strains, were strongly associated with active wheezing among children (aged 7-12 years) living in Costa Rica. Most of the wheezing children (96% in this study) were atopic, and a large majority of them (93%) were sensitized to dust mite allergen. Moreover, the titers of IgE antibody to dust mite among children enrolled for wheezing, as well as those with stable asthma, were significantly greater than to any other allergen tested. Taken together, this is the first study to demonstrate that children with high titers of IgE antibodies, which in this study were predominantly to dust mite allergen, had the greatest risk for an attack of wheezing provoked by rhinovirus. Additionally, the results demonstrate that the pathogenic effects of individual strains of rhinovirus and other respiratory tract viruses might be difficult to determine without understanding the atopic characteristics of the host.

The rationale for enrolling subjects in the ED was that children could be evaluated without knowledge about their atopic status or whether they were recently infected with a viral pathogen. In this population, subjects enrolled for wheezing and those with stable asthma had similar allergen-specific IgE responses, and their total IgE and Feno levels were significantly increased compared with those of the nonasthmatic control subjects. After adjusting for atopic characteristics, exposure to ETS at home, and daily use of inhaled and nasal steroids, the main pathogenic factor that differentiated the children who required treatment for wheezing from those with stable asthma was a positive test for rhinovirus.

In previous studies from Brazil and Trinidad, rhinovirus infections were not associated with attacks of asthma as strongly as has been reported in studies from countries with temperate climates.7, 8 Differences in lifestyle (eg, quality of drinking water, rates of helminth infection, and amount of time spent indoors [at home or in school]) might explain differences in the rates of infection; however, both Costa Rica and the region of Brazil around São Paulo have developing westernized lifestyles, and a strong association between atopy and asthma was observed in both countries. Strains of rhinovirus within groups A, B, and C were also evaluated for all positive tests for rhinovirus in our study. The majority of wheezing children were infected with group C strains (ie, 75% positive for group C and 25% positive for group A strains; both significantly associated with wheezing [Table II]). Other studies of children treated for exacerbations of asthma have also reported a higher frequency of infection with group C strains.14, 15 Thus far, no studies have shown a significant association between asthma and group B strains.

Information about the relationship between rates of infection with strains A, B, and C in the general population is unclear. Data from the nonasthmatic control subjects in the present investigation, as well as from younger children evaluated for respiratory tract infections in other studies, suggest that the frequency of infections with group A and C strains might be similar.16, 21 This suggests that the airway in patients with asthma might be more susceptible to infections with group C strains. At present, the receptor used by group C viruses to infect epithelial cells is not known. The cell-surface receptor used by group A strains is the adhesion molecule intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1).23, 24 Previous studies, including our own, indicate that the expression of ICAM-1 (both soluble and membrane ICAM-1) is reduced in the asthmatic airway,25, 26 which might give group C viruses a selective advantage for infecting the asthmatic respiratory tract epithelium. In our patient population Feno and specific IgE levels were similar among children infected with group C and group A strains. Recently, the significance of allergy in response to rhinovirus was also suggested by the significant decrease in asthma exacerbations among children treated with omalizumab, a subset of whom were infected with RV.27 The beneficial effects of inhaled corticosteroids, which also reduce TH2 inflammation and prevent asthma exacerbations during childhood, also support this observation.28, 29

High rates of sensitization to dust mite among children with asthma in Costa Rica have been described, and persistent humidity there favors mite growth throughout the year.13, 30 Although measurements of allergen exposure in homes of the children enrolled were not done, previous investigations from Costa Rica suggest that exposure levels based on measurements of guanine to estimate mite allergen concentrations in dust samples are increased throughout the year but might be higher during the rainy season.30 Persistent humidity supporting mite growth is also present in New Zealand and the United Kingdom, where high titers of IgE antibodies to dust mite and the risk of asthma have also been observed.31, 32 In the present study high titers of IgE antibody to dust mite were strongly associated with asthma and significantly increased the risk for acute wheezing more than to any other allergen tested. Most striking was the significant increase in the probability of wheezing with a recent rhinovirus infection among children with titers of IgE antibodies to D pteronyssinus of 17.5 IU/mL or greater. Other environmental antigens capable of stimulating IgE antibodies might exist that were not evaluated. However, as judged by the prevalence and titers of IgE antibody, none of the other allergens included in this study compared with the results observed for dust mite.

The observation that the generation of Feno in the asthmatic airway correlates with sensitization and exposure to inhaled allergens has been described previously, and levels of Feno among the asthmatic children (both those with current wheeze and stable asthma) in the present study were significantly higher than those among the nonasthmatic control subjects.32, 33, 34 These results are consistent with results from our experimental challenges with RV-16, demonstrating that the levels of Feno were significantly increased before the virus inoculation among asthmatic patients with high levels of total IgE.25 Together, the results suggest that preexisting allergic inflammation is the main risk factor for an asthmatic response to rhinovirus. In the present study the positive correlation between titers of IgE to D pteronyssinus, D farinae, or B tropicalis and Feno levels provides further evidence for the relevance of dust mite allergen to the pathogenesis of airway inflammation.

In conclusion, this investigation highlights the significant risk for asthma attacks caused by rhinovirus among children with high titers of IgE antibodies, which was most often associated with sensitization to dust mite allergen in Costa Rica. Thus far, antiviral treatments, including vaccines, to treat infections with rhinovirus have been difficult to develop because of antigenic diversity among rhinovirus strains. The predisposition of asthmatic patients to become infected with group C strains might offer a more targeted approach for developing antiviral treatments. However, this approach would not be effective for the 40% of wheezing children who did not have positive test results for rhinovirus in this study and might not be effective in preventing attacks of asthma caused by group A strains. Alternatively, treatments focused on decreasing allergic airway inflammation could provide a broader approach to prevent and/or decrease the severity of asthma exacerbations caused by rhinovirus. Thus results from this study provide strong evidence that characterizing the atopic status of asthmatic children in greater detail, including their titers of allergen-specific IgE antibodies, is needed both to enhance investigations focused on mechanisms of rhinovirus-induced attacks of asthma and to identify children who are most likely to benefit from allergen-specific therapies.

Key messages.

-

•

Rhinovirus infections, both group C and group A strains, were significantly associated with asthma exacerbations among Costa Rican children evaluated during the dry and rainy seasons.

-

•

Most asthmatic children (93% with current wheeze) were sensitized to dust mite allergen, and titers of IgE to mite allergens correlated significantly with levels of total IgE and Feno.

-

•

High titers of allergen-specific IgE to dust mite significantly increased the risk for acute wheezing provoked by rhinovirus.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lyn Melton for her time and help in preparing this manuscript.

Footnotes

Supported by the Cove Point Foundation, National Institutes of Health grants R01 AI020565 and U19 AI070364, and the University of Virginia Children's Hospital Research Fund.

Disclosure of potential conflict of interest: T. A. E. Platts-Mills has consultant arrangements with IBT/Viracor Labs and has received research support and honorarium from Phadia/Thermo Fisher. J. W. Steinke has received payment as a Board Review Course Speaker for the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology; has received research support from the National Institutes of Health and Medtronic; and is the AIR Committee Chair for the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. J. Kennedy has received research support from the National Institutes of Health and the University of Virginia. P. W. Heymann has received research support from the National Institutes of Health, the Cove Point Foundation, and the University of Virginia Children's Hospital. The rest of the authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Methods

Method for collecting nasal washes for viral analyses

Nasal washes were obtained for viral analyses from each child while they were breath holding in a sitting position. By using a Mucosal Atomizing Device (Wolfe Tory Medical, Inc, Salt Lake City, Utah), 1.5 mL of PBS was instilled into each nostril. Each nostril was washed separately. Wash fluid and secretions were aspirated immediately by using a BBG Nasal Aspirator (Codan US Corp, Santa Ana, Calif) into a sterile mucus trap attached to wall suction. One milliliter of PBS containing 0.25% gelatin for stabilization of protein in the wash fluid was aspirated through the suction device to rinse any residual secretions into the trap. The combined washes from both nostrils resulted in volumes of 2.5 to 3 mL of wash fluid and nasal secretions. A plastic transfer pipette was used to mix secretions with wash fluid, and 1-mL aliquots were frozen at −80°C for subsequent analyses.

Table E1.

Demographics and subjects' characteristics (February compared with October enrollments)

| Children with current wheeze |

Children with stable asthma |

Nonasthmatic control subjects |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| February (n = 44) | October (n = 51) | February (n = 35) | October (n = 30) | February (n = 57) | October (n = 69) | |

| Mean age (y) | 8.7 | 9.0 | 9.3 | 8.8 | 9.8 | 9.1 |

| Sex (% male) | 57% | 59% | 54% | 63% | 39% | 54% |

| ED treatment for asthma, last 12 mo¶¶ | 89% | 90% | 91% | 77% | NA | NA |

| Hospitalization for asthma, last 12 mo## | 7% | 14% | 6% | 27%‡‡ | NA | NA |

| Asthma medication use | ||||||

| Last 12 mo∗∗∗ | 82% | 74% | 86% | 80% | NA | NA |

| Last month | 43% | 74%§§ | 31% | 73%‖‖ | NA | NA |

| Percent with daily use of: | ||||||

| Inhaled steroids | 36%‖ | 35% | 66% | 40% | NA | NA |

| Nasal steroids | 4%‖ | 6%§ | 31% | 20% | NA | NA |

| Montelukast | 11% | 14% | 15% | 17% | NA | NA |

| >10 d of school missed for asthma††† | 18%§§ | 33% | 26% | 40% | NA | NA |

| Indoor dog/cat exposure‡‡‡ | 9%*/23% | 6%/18% | 9%*/23% | 13%/20% | 25%/16% | 13%/22% |

| Worst season (% dry/rainy/not seasonal)§§§ | 7%/64%/29% | 2%/54%/44% | 5%/68%/26% | 0%/62%/38% | NA | NA |

| Family history of asthma: | ||||||

| Mother | 14%§§ | 43%‡ | 26%** | 37%** | 5% | 14% |

| Father | 20%† | 14% | 17%# | 20%# | 2% | 6% |

| ETS exposure‖‖‖ | 20% | 31% | 11% | 10% | 28% | 26% |

| ETS exposure from mother¶¶¶ | 2% | 6% | 6% | 3% | 9% | 9% |

| ETS exposure from father### | 7% | 18%§ | 3% | 3% | 21%# | 17%# |

NA, Not applicable.

Symbols marking significant differences between groups within each enrollment period include the following: wheezing children versus nonasthmatic control subjects (*P < .05, †P < .01, and ‡P < .001); wheezing children versus children with stable asthma (§P < .05, ‖P < .01, and ¶P < .001); and children with stable asthma versus nonasthmatic control subjects (#P < .05, **P < .01, and ††P < .001). Significant differences between the February and October enrollments for each group are indicated as follows: ‡‡P < .05, §§P < .01, and ‖‖P < .001.

Percentage of children requiring treatment in the ED or hospitalization for asthma during the last 12 months.

Percentage of children using medications (bronchodilator, controller, or both) for asthma during the timeframe indicated.

Percentage of children using inhaled corticosteroids, nasal steroids, or montelukast daily.

Percentage of children who missed more than 10 days of school for asthma during the previous year.

Percentage of children with dog or cat exposure in the home.

Percentage of parents reporting that their child's asthma was worse during the rainy or dry season or that their asthma symptoms were not seasonal. Both wheezing children and those with stable asthma enrolled in February and October experienced more asthma symptoms during the rainy compared with the dry season (P < .001).

Percentage of children exposed to at least 1 person at home who smoked 5 or more cigarettes a day.

Percentage of children whose mother or father smoked 5 or more cigarettes a day.

Table E2.

Gene sequencing identification of rhinovirus strains according to group (A, B, or C)

| Group A |

Group C |

Group B |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain | Positive test results per strain | Strain | Positive test results per strain | Strain | Positive test results per strain | |

| Children with current wheeze | RVA(7) | 2 | RVC | 46 | RVB(86)∗ | 1 |

| RVA(24) | 1 | |||||

| RVA(33) | 1 | |||||

| RVA(44) | 3 | |||||

| RVA(46) | 1 | |||||

| RVA(58) | 1 | |||||

| RVA(68) | 1 | |||||

| RVA(94) | 1 | |||||

| RVA(98)∗ | 2 | |||||

| Children with stable asthma | RVA(1B) | 1 | RVC | 4 | RVB(48) | 1 |

| RVA(NT) | 1 | RVB(86) | 1 | |||

| Control subjects | RVA(36) | 1 | RVC | 7 | RVB(83) | 1 |

| RVA(39) | 2 | RVB(86) | 2 | |||

| RVA(46) | 1 | |||||

| RVA(82) | 2 | |||||

| RVA(89) | 1 | |||||

| RVA(NT) | 1 | |||||

NT, New type.

Coinfection with RVA(98) and RVB(86).

Table E3.

Assessments of total IgE, allergen-specific IgE antibody, and Feno levels (February compared with October enrollments)

| Children with current wheeze (n = 95) |

Children with stable asthma (n = 65) |

Control subjects (n = 123) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| February (n = 43) |

October (n = 52) |

February (n = 35) |

October (n = 30) |

February (n = 57) |

October (n = 66) |

|||||||

| % Positive§§ | IgE antibody titers‖‖ | % Positive§§ | IgE antibody titers‖‖ | % Positive§§ | IgE antibody titers‖‖ | % Positive§§ | IgE antibody titers‖‖ | % Positive§§ | IgE antibody titers‖‖ | % Positive§§ | IgE antibody titers‖‖ | |

| Total serum IgE (IU/mL)‡‡ | 456 (332-627)‡ | 504 (377-673)‡ | 328 (164-657)** | 374 (206-681)†† | 111 (76-162) | 86 (59-127) | ||||||

| Feno (ppb) | 41 (32-53)‡§ | 30 (24-37)‡ | 27 (21-36)‡ | 23 (17-32)* | 13 (10-16) | 15 (13-19) | ||||||

| IgE antibody (IU/mL) to: | ||||||||||||

| Any allergen | 93‡ | NA | 98‡ | NA | 79** | NA | 90†† | NA | 49 | NA | 58 | NA |

| D pteronyssinus | 86‡ | 21 (11-41)‡ | 92‡ | 29 (16-53)‡ | 74†† | 8 (4-17)†† | 83†† | 15 (7-34)†† | 35 | 1.2 (0.7-2.2) | 44 | 1.2 (0.7-2.1) |

| D farinae | 88‡ | 18 (10-32)‡§ | 96‡ | 19 (11-32)‡ | 74†† | 6 (3-12)†† | 83†† | 10 (5-20)†† | 37 | 1.1 (0.6-1.8) | 41 | 1.1 (0.7-1.7) |

| B tropicalis | 91‡ | 12 (7-22)‡ | 90‡ | 12 (7-21)‡ | 74** | 6 (3-11)†† | 90†† | 10 (5-20)†† | 40 | 0.9 (0.5-1.5) | 39 | 1.1 (0.7-1.8) |

| B germanica | 48† | 1.6 | 58‡ | 2.0 | 41 | 2.5 | 40 | 4.2# | 23 | 1.9 | 24 | 1.4 |

| P americana | 36* | 1.2 | 38‡ | 1.6 | 32# | 1.3 | 33** | 2.3 | 14 | 1.2 | 9 | 1.4 |

| A lumbricoides | 51‡ | 1.6 | 35 | 2.0 | 30** | 2.1 | 43# | 2.1 | 18 | 1.0 | 18 | 1.0 |

| Alternaria species | 0 | NA | 8† | 2.4 | 3 | NA | 4 | NA | 0 | NA | 0 | NA |

| Aspergillus species | 7 | 0.7 | 16† | 0.9 | 12 | 0.8 | 7 | 0.5 | 4 | 0.8 | 2 | 2.6 |

| Dog dander | 17 | 1.1 | 31‡ | 1.4 | 9 | 1.1 | 26** | 1.1 | 9 | 1.0 | 3 | 2.0 |

| Cat dander | 12 | 1.3 | 20* | 2.1 | 12 | 2.1 | 18 | 3.9 | 10 | 1.8 | 6 | 2.6 |

| Bahia grass | 7 | 1.9 | 14 | 1.2 | 12 | 13.5 | 14 | 1.7 | 7 | 1.0 | 6 | 2.9 |

NA, Not applicable.

Symbols marking significant differences between groups within the same enrollment period (February or October) include the following: wheezing children versus nonasthmatic control subjects (*P < .05, †P < .01, and ‡P < .001); wheezing children versus children with stable asthma (§P < .05, ‖P < .01, and ¶P < .001); and children with stable asthma versus nonasthmatic control subjects (#P < .05, **P < .01, and ††P < .001).

GMs for total serum IgE and Feno levels are followed by 95% CIs in parentheses.

Percentage of children with IgE antibody levels of 0.35 IU/mL or greater to each allergen.

IgE antibody titers are shown as GMs. GMs for the dust mite species are followed by 95% CIs in parentheses. GMs for other allergens include only children whose allergen-specific IgE levels were 0.35 IU/mL or greater.

Table E4.

IgE antibody and group of subjects testing positive for enterovirus or RSV

| Virus | Group | Specific IgE antibody titers |

Total IgE | Feno (ppb) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B germanica | D pteronyssinus | D farinae | B tropicalis | Cat dander | Ascaris species | ||||

| Enterovirus∗ | Current wheeze | <0.35 | 94.7 | 53.1 | 1.20 | <0.35 | <0.35 | 591 | 12 |

| Current wheeze | <0.35 | 3.67 | 2.31 | <0.35 | <0.35 | <0.35 | 100 | 31 | |

| Stable asthma | 0.64 | 8.96 | 4.90 | 2.98 | <0.35 | <0.35 | 273 | 26 | |

| Current wheeze† | 1.77 | 782 | 415 | 558 | <0.35 | 0.93 | 4712 | 14 | |

| Current wheeze | <0.35 | 2.52 | 19.4 | 89.3 | <0.35 | 4.11 | 769 | 24 | |

| Current wheeze | <0.35 | 651 | 362 | 22.5 | 17.4 | <0.35 | 1365 | 62 | |

| Current wheeze | <0.35 | 2.31 | 1.32 | 6.77 | <0.35 | <0.35 | 181 | 22 | |

| RSV | Control | <0.35 | 12.5 | 7.47 | 3.61 | <0.35 | 0.37 | 119 | 31 |

| Current wheeze | <0.35 | <0.35 | 0.59 | 0.68 | <0.35 | <0.35 | 144 | 5 | |

| Current wheeze | 0.71 | 77.9 | 34.0 | 5.84 | <0.35 | <0.35 | 414 | 29 | |

| Current wheeze | 0.54 | 19.8 | 7.96 | 3.82 | <0.35 | <0.35 | 890 | 14 | |

| Current wheeze | <0.35 | 25.0 | 6.48 | 130 | 10.1 | 2.99 | 543 | 48 | |

| Current wheeze‡ | 0.47 | <0.35 | <0.35 | <0.35 | <0.35 | <0.35 | 55 | 19 | |

| Current wheeze | 1.11 | 1.08 | 0.72 | <0.35 | <0.35 | <0.35 | 460 | 11 | |

| Current wheeze | <0.35 | 186 | 75.1 | 23.9 | <0.35 | 0.61 | 476 | 29 | |

| Current wheeze | <0.35 | 12.3 | 11.0 | 30.3 | <0.35 | <0.35 | 102 | 20 | |

| Current wheeze | <0.35 | 192 | 78.4 | 38.8 | <0.35 | <0.35 | 638 | 6 | |

Titers of specific and total serum IgE antibodies are in international units per milliliter. Specific IgE antibody titers in boldface are considered positive, and those in italics are considered high titer (≥17.5 IU/mL).

One control subject did not have serum IgE data but had positive results for enterovirus by using real-time PCR on nasal secretions.

This subject with current wheeze was coinfected with enterovirus and RSV.

This subject with current wheeze was coinfected with RSV and human rhinovirus group C.

References

- 1.Heymann P.W., Carper H.T., Murphy D.D., Platts-Mills T.A.E., Patrie J., McLaughlin A.P. Viral infections in relation to age, atopy, and the season of admission among children hospitalized for wheezing. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:239–247. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnston S.L., Pattemore P.K., Sanderson G., Smith S., Lampe F., Josephs L. Community study of role of viral infections in exacerbations of asthma in 9 to 11 year old children. BMJ. 1994;310:1225–1228. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6989.1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rawlinson W.D., Waliuzzaman Z., Carter I.W., Belessis Y.C., Gilbert K.M., Morton J.R. Asthma exacerbations in children associated with rhinovirus but not human metapneumovirus infection. J Infect Dis. 2003;187:1314–1318. doi: 10.1086/368411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams J.V., Tollefson S.J., Heymann P.W., Carper H.T., Patrie J., Crowe J.E. Human metapneumovirus infection in children hospitalized for wheezing. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:1311–1312. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rakes G.P., Arruda E., Ingram J.M., Hoover G.E., Zambrano J.C., Hayden F.G. Rhinovirus and respiratory syncytial virus in wheezing children requiring emergency care. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:785–790. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.3.9801052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green R.M., Custovic A., Sanderson G., Hunt J., Johnston S.L., Woodcock A. Synergism between allergens and viruses and risk of hospital admission with asthma: case-control study. BMJ. 2002;324:763. doi: 10.1136/bmj.324.7340.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Camara A.A., Silva J.M., Ferriani V.P., Tobias K.R., Macedo I.S., Padovani M.A. Risk factors for wheezing in a subtropical environment: role of respiratory viruses and allergen sensitization. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:551–557. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matthew J., Pinto Pereira L.M., Pappas T.E., Swenson C.A., Grindle K.A., Roberg K.A. Distribution and seasonality of rhinovirus and other respiratory viruses in a cross-section of asthmatic children in Trinidad, West Indies. Ital J Pediatr. 2009;35:16. doi: 10.1186/1824-7288-35-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hunninghake G.M., Soto-Quiros M.E., Avila L., Ly N.P., Liang C., Sylvia J.S. Sensitization to Ascaris lumbricoides and severity of childhood asthma in Costa Rica. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:654–661. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.12.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Normas de Atencion Integral de Salud, Primer Nivel de Atencion. Caja Costarricense de Seguridad Social; San Jose (Costa Rica): 1995. p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soto-Quiros M.E., Soto-Martinez M., Hanson L.A. Epidemiological studies of the very high prevalence of asthma and related symptoms among school children in Costa Rica from 1989 to 1998. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2002;123:342–349. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3038.2002.02035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Worldwide variation in prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and atopic eczema: ISAAC. The International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) Steering Committee. Lancet. 1998;351:1225–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Celedón J.C., Soto Quirós M., Silverman E.K., Hanson L.Å., Weiss S.T. Risk factors for childhood asthma in Costa Rica. Chest. 2001;120:785–790. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.3.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khetsuriani N., Lu X., Teague W.G., Kazerouni N., Anderson L., Erdman D.D. Novel human rhinoviruses and exacerbations of asthma in children. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1793–1796. doi: 10.3201/eid1411.080386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bizzintino J., Lee W.M., Laing I.A., Vang F., Pappas T., Zhang G. Association between human rhinovirus C and severity of acute asthma in children. Eur Respir J. 2011;37:1037–1042. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00092410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller E.K., Edwards K.M., Weinberg G.A., Iwane M.K., Griffin M.R., Hall C.B. New Vaccine Surveillance Network. A novel group of rhinoviruses is associated with asthma hospitalizations. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;123:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arruda E., Hayden F.G. Detection of human rhinovirus RNA in nasal washings by PCR. Mol Cell Probes. 1993;7:373–379. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.1993.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pitkaranta A., Arruda E., Malberg H., Hayden F.G. Detection of rhinovirus in sinus brushings of patients with acute community acquired sinusitis by reverse transcription PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1791–1793. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.7.1791-1793.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kodani M., Yang G., Conklin L.M., Travis T.C., Whitney C.G., Anderson L.J. Application of TaqMan low-density arrays for simultaneous detection of multiple respiratory pathogens. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:2175–2182. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02270-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dare R.K., Fry A.M., Chittaganpitch M., Sawanpanyalert P., Olsen S.J., Erdman D.D. Human coronavirus infections in rural Thailand: a comprehensive study using real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction assays. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:1321–1328. doi: 10.1086/521308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iwane M.K., Prill M.M., Lu X., Miller E.K., Edwards K.M., Hall C.B. Human rhinovirus species associated with hospitalizations for acute respiratory illness in young US children. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:1702–1710. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hasegawa S., Hirano R., Okamoto-Nakagawa R., Ichiyama T., Shirabe K. Enterovirus 68 infection in children with asthma attacks: virus-induced asthma in Japanese children. Allergy. 2011;66:1618–1620. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bochkov Y.A., Palmenberg A.C., Lee W.M., Rathe J.A., Amineva S.P., Xin S. Molecular modeling, organ culture and reverse genetics for a newly identified human rhinovirus C. Nat Med. 2011;17:627–632. doi: 10.1038/nm.2358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Staunton D.E., Merlizzi V.J., Rothlein R., Barton R., Marlin S.D., Springer T. A cell adhesion molecule, ICAM-1, is the major surface receptor for rhinoviruses. Cell. 1989;6:849–853. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90689-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zambrano J.C., Carper H.T., Rakes G.P., Patrie J., Murphy D.D., Platts-Mills T.A.E. Experimental rhinovirus challenges in adults with mild asthma: the response to infection in relation to IgE. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:1008–1016. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wark P.A., Johnston S.L., Bucchieri F., Powell R., Puddicombe S., Laza-Stanca V. Asthmatic bronchial epithelial cells have a deficient innate immune response to infection with rhinovirus. J Exp Med. 2005;201:937–947. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Busse W.W., Morgan W.J., Gergen P.J., Mitchell H., Gern J.E., Liu A. Randomized trial of omalizumab (anti-IgE) for asthma in inner-city children. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1005–1015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1009705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Volovitz B. Inhaled budesonide in the management of acute worsenings and exacerbations of asthma: a review of the evidence. Respir Med. 2007;101:685–695. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sorkness C.A., Lemanske R.F., Mauger D.T., Boehmer M.A., Chinchilli V.M., Martinez F.D. Long-term comparison of 3 controller regimens for mild-moderate persistent childhood asthma: the Pediatric Asthma Controller Trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Soto-Quirós M., Stahol A., Calderón O., Sánchez C., Hanson L.A., Belin L. Guanine, mite, and cockroach allergens in Costa Rican homes. Allergy. 1998;53:499–505. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.1998.tb04087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Erwin E.A., Wickens K., Custis N.J., Siebers R., Woodfolk J., Barry D. Cat and dust mite sensitivity and tolerance in relation to wheezing among children raised with high exposure to both allergens. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:74–79. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crane J., Lampshire P., Wickens K., Epton M., Siebers R., Inham T. Asthma, atopy and exhaled nitric oxide in a cohort of 6-year-old New Zealand children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2012;23:59–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2011.01227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Spanier A.J., Hornung R.W., Kahn R.S., Lierl M.B., Lanphear B.P. Seasonal variation and environmental predictors of exhaled nitric oxide in children with asthma. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2008;43:576–583. doi: 10.1002/ppul.20816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jackson D.J., Virnig C.M., Gangnon R.E., Evans M.D., Roberg K.A., Anderson E.L. Fractional exhaled nitric oxide measurements are most closely associated with allergic sensitization in school-age children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:949–953. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]