The cloning, expression and purification of different fragments of the S. pyogenes SpyCEP protein are reported. Preliminary X-ray diffraction analysis of a 1580-residue selenomethionine-labelled ectodomain fragment is described.

Keywords: vaccine antigens, GAS, auto-proteases, Streptococcus pyogenes, SpyCEP

Abstract

Streptococcus pyogenes (Group A streptococcus; GAS) is an important human pathogen against which an effective vaccine does not yet exist. The S. pyogenes protein SpyCEP (S. pyogenes cell-envelope proteinase) is a surface-exposed subtilisin-like serine protease of 1647 amino acids. In addition to its auto-protease activity, SpyCEP is capable of cleaving interleukin 8 and related chemokines, contributing to GAS immune-evasion strategies. SpyCEP is immunogenic and confers protection in animal models of GAS infections. In order to structurally characterize this promising vaccine candidate, several SpyCEP protein-expression constructs were designed, cloned, produced in Escherichia coli, purified by affinity chromatography and subjected to crystallization trials. Crystals of a selenomethionyl form of a near-full-length SpyCEP ectodomain were obtained. The crystals diffracted X-rays to 3.3 Å resolution and belonged to space group C2, with unit-cell parameters a = 139.2, b = 120.4, c = 104.3 Å, β = 111°.

1. Introduction

The Gram-positive bacterium Streptococcus pyogenes (Group A streptococcus; GAS) is a globally important cause of human morbidity and mortality. GAS causes mild and severe diseases, including acute rheumatic fever, rheumatic heart disease, post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis and invasive infections. It is estimated that over 18 million cases of severe GAS disease exist worldwide, causing >517 000 deaths annually (Carapetis et al., 2005 ▶). The development of a vaccine preventing GAS diseases is therefore an important goal in global human healthcare.

Independent searches for GAS vaccine candidates have led to the identification of a highly conserved 180 kDa antigen termed SpyCEP (S. pyogenes cell-envelope proteinase; Spy0416). SpyCEP is immunogenic in animals and humans and, either alone or in a combination of three GAS proteins, SpyCEP confers protection in animals against multiple GAS serotypes (Lei et al., 2000 ▶; Rodríguez-Ortega et al., 2006 ▶; Fritzer et al., 2009 ▶; Zingaretti et al., 2010 ▶; Bensi et al., 2012 ▶).

SpyCEP is a subtilisin-like serine protease that degrades chemokines, preventing neutrophil recruitment to infection sites (Edwards et al., 2005 ▶); for example, surface-bound SpyCEP can cleave interleukin 8 (Chiappini et al., 2012 ▶). SpyCEP contains distinct N-terminal and C-terminal domains separated by autocleavage between residues Gln244 and Ser245. Interestingly, both domains contribute residues to the catalytic triad (Asp151, His279 and Ser617) and can be produced separately for subsequent reconstitution of the functional enzymatic complex (Fritzer et al., 2009 ▶; Zingaretti et al., 2010 ▶). The three-dimensional structure of SpyCEP is currently unknown; the closest known homologous structure is likely to be the S. pyogenes C5a peptidase (UniProt P15926; PDB entry 3eif; Kagawa et al., 2009 ▶), which shares 32% sequence identity with SpyCEP residues Ser118–Leu1128.

In light of the global importance of GAS disease, and the promise of SpyCEP as a vaccine candidate, we sought to determine the structure of SpyCEP by X-ray crystallography to gain further insights into its structural, functional and immunological properties.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cloning, expression and purification of SpyCEP proteins

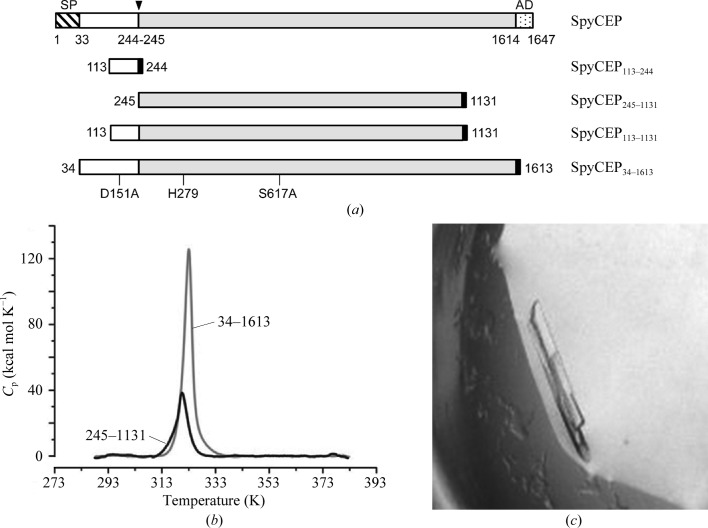

Using PIPE PCR cloning (Klock & Lesley, 2009 ▶) and the GAS M1 strain SpyCEP ectodomain (residues 34–1613; UniProt Q9A180) in pET-21b (Zingaretti et al., 2010 ▶), three SpyCEP constructs were prepared in pET-28a, termed SpyCEP113–244, SpyCEP245–1131 and SpyCEP113–1131 (Fig. 1 ▶ a), excluding residues 33–112 because of predicted disorder and excluding residues 1132 onwards in order to mimic the C5a peptidase construct used for structure determination (Kagawa et al., 2009 ▶). The catalytic residues Asp151 and Ser617 were mutated to Ala, as described previously (Zingaretti et al., 2010 ▶), to minimize proteolysis during crystallization. Each construct was cloned with an additional Met at the N-terminus, while at the C-terminus each construct included a hexapeptide linker (sequence GSALAE) added between the SpyCEP residues and the His6 tag to facilitate access to the C-terminal His6 tag.

Figure 1.

(a) Domain architecture of GAS M1 strain SpyCEP (UniProt Q9A180) and the boundaries of the expression constructs prepared: SpyCEP113–244 (Thr113–Gln244; white), SpyCEP245–1131 (Ser245–Thr1131; grey), SpyCEP113–1131 (Thr113–Thr1131) and SpyCEP34–1613, the full-length ectodomain (Ala34–Leu1614) lacking the C-terminal LPXTG anchor domain (AD, dotted box). The black boxes represent the hexahistidine tags, all of which are at the C-termini. The subtilisin-like protease is composed of two regions spanning residues 124–420 and 572–687. (b) DSC profiles of SpyCEP245–1131 and SpyCEP34–1613 showing a clear unfolding transition with similar T m of 320.5–323 K. (c) The crystal of SpyCEP34–1613 ectodomain (selenomethionyl form) used for data collection reported here.

SpyCEP proteins were produced in Escherichia coli BL21 in rich medium or in E. coli B834 in M9 medium containing 40 mg l−1 selenomethionine, 30 µg ml−1 kanamycin with induction by 0.4 mM IPTG and shaking overnight at 303 K. Cells were harvested, lysed by sonication and His6-tagged proteins were purified via Ni-affinity, Q Sepharose anion-exchange and size-exclusion chromatography on a Superdex 75 column equilibrated in 20 mM Tris–HCl, 150 mM NaCl pH 7.2.

2.2. Crystallization

Prior to crystallization, sample purity was assessed by SDS–PAGE. Thermal stability was assessed by differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) performed on a MicroCal VP-Capillary DSC instrument (GE Healthcare) ranging from 283 to 383 K with a thermal ramp rate 200 K h−1 and 4 s filter period using SpyCEP samples at 0.5 mg ml−1 in buffer consisting of 20 mM Tris–HCl, 150 mM NaCl pH 7.2, ±10 mM CaCl2. Highly purified samples of (i) SpyCEP34–1613 ectodomain; (ii) the individual SpyCEP113–244, SpyCEP245–1131 and SpyCEP113–1131 proteins; and (iii) the reconstituted SpyCEP113–244–SpyCEP245–1131 complex were concentrated to 5–15 mg ml−1 and crystallization experiments using five commercially available screens were prepared using a Crystal Gryphon liquid dispenser (Art Robbins Instruments). Experiments were performed at 277 and 293 K. Table 1 ▶ reports the conditions used to obtain SpyCEP34–1613 crystals.

Table 1. Crystallization conditions for the selenomethionine derivative of SpyCEP34–1613 .

| Method | Sitting-drop vapour diffusion |

| Plate type | 96-well round-bottom Intelli-Plate |

| Temperature (K) | 293 |

| Protein concentration (mg ml−1) | 6.6 |

| Buffer composition of protein solution | 20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.2, 150 mM NaCl |

| Composition of reservoir solution | 0.2 M sodium acetate, 20%(w/v) polyethylene glycol 3350 pH 8.0 |

| Volume (nl) and ratio of drop | 100 (1:1) |

| Volume of reservoir (µl) | 80 |

2.3. Data collection and processing

Crystals were transferred into a stabilizing solution (reservoir solution with 20% ethylene glycol), flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen and shipped for diffraction data collection on beamline ID14-4 at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF), France. Data collection was performed at 100 K using an ADSC Q315r detector. Unit-cell parameters and space group were determined using XDS (Kabsch, 2010 ▶) and POINTLESS (Evans, 2011 ▶). Table 2 ▶ summarizes the key data-collection and processing statistics for the selenomethionine-derivative of SpyCEP34–1613.

Table 2. Data collection and processing.

Values in parentheses are for the outer shell.

| Diffraction source | ID14-4, ESRF |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.97974 |

| Temperature (K) | 100 |

| Detector | Q315r ADSC |

| Crystal–detector distance (mm) | 525 |

| Rotation range per image (°) | 0.6 |

| Total rotation range (°) | 360 |

| Exposure time per image (s) | 0.1 |

| Space group | C2 |

| Unit-cell parameters (Å, °) | a = 139.2, b = 120.4, c = 104.3, α = γ = 90, β = 111 |

| Mosaicity (°) | 0.5 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 44–3.3 (3.45–3.30) |

| Total No. of reflections | 180416 (19724) |

| No. of unique reflections | 47163 (5646) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.0 (95.3) |

| Multiplicity | 3.8 (3.5) |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉 | 8.8 (2.3) |

| R merge | 0.15 (0.56) |

| R r.i.m. | 0.173 (0.667) |

| Overall B factor from Wilson plot (Å2) | 41.7 |

3. Results and discussion

A panel of expression constructs of the S. pyogenes spyCEP gene was successfully cloned to encode C-terminally His6-tagged proteins. The constructs were designed for crystallization trials of the SpyCEP34–1613 ectodomain and shorter constructs spanning the SpyCEP113–244 region (including Pro-domain residues) and the larger SpyCEP245–1131 region (including most catalytic domain residues) sharing 32% sequence identity with C5a peptidase (Fig. 1 ▶ a). Proteins were expressed in E. coli and purified using standard methods. Size-exclusion chromatography profiles indicated monodisperse monomers with apparent sizes matching the predicted molecular weights of 98.4, 113.4 and 175.0 kDa for SpyCEP245–1131, SpyCEP113–1131 and SpyCEP34–1613 proteins, respectively. Yields of ∼3 mg highly purified protein from 1 l growth medium were obtained.

The stability of SpyCEP34–1613, and the relative instability of the SpyCEP113–244 domain, have been described previously (Zingaretti et al., 2010 ▶). Here, a new construct, SpyCEP245–1131, lacking ∼500 C-terminal residues, was prepared. The SpyCEP245–1131 protein was soluble, readily purified and its stability was confirmed by DSC, revealing a melting temperature (T m) of 320.5 K (Fig. 1 ▶ b). The additional ∼700 residues in the full-length construct SpyCEP34–1613 appear to require more heat to induce unfolding (the peak is larger), although the thermostability of the protein is only slightly increased: T m = 323 K (Fig. 1 ▶ b). Although the C5a peptidase structure reveals a Ca2+ ion coordinated by five residues conserved in SpyCEP, the addition of Ca2+ did not significantly increase the T m or the crystallization success rate for SpyCEP. The DSC data demonstrate that the SpyCEP245–1131 apoprotein designed herein is stable and has a T m that is encouraging for crystallization trials (Dupeux et al., 2011 ▶).

Because of the limited sequence identity of SpyCEP with existing structural models (the C5a peptidases from S. pyogenes and S. agalactiae; Brown et al., 2005 ▶), we proceeded with attempts to crystallize selenomethionine derivatives of SpyCEP, which contains 29 methionines. After multiple screens using SpyCEP245–1131, SpyCEP113–1131, the SpyCEP113–244–SpyCEP245–1131 complex and SpyCEP34–1613 samples, crystals suitable for X-ray diffraction were obtained only for the SpyCEP34–1613 protein (Fig. 1 ▶ c, Table 1 ▶).

A complete diffraction data set to 3.3 Å resolution was collected from a single crystal at 100 K using synchrotron radiation on the ID14-4 beamline at the ESRF, Grenoble. A selenium scan on the same crystal was used to define the peak wavelength (0.97974 Å) and, although a multiple anomalous dispersion experiment was attempted, radiation damage only permitted data collection for one ‘peak’ data set. Preliminary analysis revealed that the crystals belonged to space group C2, with unit-cell parameters a = 139.2, b = 120.4, c = 104.3 Å, β = 111°. Assuming the presence of only one SpyCEP34–1613 molecule (calculated molecular weight 175.0 kDa) per crystal asymmetric unit, the calculated Matthews coefficient is 2.3 Å3 Da−1 (Matthews, 1968 ▶), with 47.3% solvent content. The diffraction data were processed using XDS and XSCALE (Kabsch, 2010 ▶) and the statistics are summarized in Table 2 ▶. Structure determination by molecular replacement (MR) either using the C5a peptidases as search models or using automated MR pipelines did not yield a positive solution. However, a weak anomalous signal from selenium was detected to ∼5 Å resolution, as measured using phenix.xtriage in the PHENIX software suite (Adams et al., 2010 ▶). Structure determination by either single or multiple anomalous dispersion methods, requiring the production of improved selenomethionine-derivative SpyCEP34–1613 crystals, is currently ongoing.

Acknowledgments

Francesca Abate holds a Novartis Vaccines PhD Academy Fellowship registered with the University of Siena, Italy. We wish to thank Daniele Veggi, Paola Lo Surdo, Silvana Savino, Mikkel Nissum, Domenico Maione, Guido Grandi, Ilaria Ferlenghi, Paolo Costantino (Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics) and Professor Cosima T. Baldari (University of Siena) for their kind support.

References

- Adams, P. D. et al. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 213–221.

- Bensi, G. et al. (2012). Mol. Cell. Proteomics, 11, M111.015693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Brown, C. K., Gu, Z.-Y., Matsuka, Y. V., Purushothaman, S. S., Winter, L. A., Cleary, P. P., Olmsted, S. B., Ohlendorf, D. H. & Earhart, C. A. (2005). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 102, 18391–18396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Carapetis, J. R., Steer, A. C., Mulholland, E. K. & Weber, M. (2005). Lancet Infect. Dis. 5, 685–694. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chiappini, N., Seubert, A., Telford, J. L., Grandi, G., Serruto, D., Margarit, I. & Janulczyk, R. (2012). PLoS One, 7, e40411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dupeux, F., Röwer, M., Seroul, G., Blot, D. & Márquez, J. A. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 915–919. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Edwards, R. J., Taylor, G. W., Ferguson, M., Murray, S., Rendell, N., Wrigley, A., Bai, Z., Boyle, J., Finney, S. J., Jones, A., Russell, H. H., Turner, C., Cohen, J., Faulkner, L. & Sriskandan, S. (2005). J. Infect. Dis. 192, 783–790. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Evans, P. R. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 282–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fritzer, A., Noiges, B., Schweiger, D., Rek, A., Kungl, A. J., von Gabain, A., Nagy, E. & Meinke, A. L. (2009). Biochem. J. 422, 533–542. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kabsch, W. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kagawa, T. F., O’Connell, M. R., Mouat, P., Paoli, M., O’Toole, P. W. & Cooney, J. C. (2009). J. Mol. Biol. 386, 754–772. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Klock, H. E. & Lesley, S. A. (2009). Methods Mol. Biol. 498, 91–103. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lei, B., Mackie, S., Lukomski, S. & Musser, J. M. (2000). Infect. Immun. 68, 6807–6818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Matthews, B. W. (1968). J. Mol. Biol. 33, 491–497. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Ortega, M. J., Norais, N., Bensi, G., Liberatori, S., Capo, S., Mora, M., Scarselli, M., Doro, F., Ferrari, G., Garaguso, I., Maggi, T., Neumann, A., Covre, A., Telford, J. L. & Grandi, G. (2006). Nature Biotechnol. 24, 191–197. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zingaretti, C., Falugi, F., Nardi-Dei, V., Pietrocola, G., Mariani, M., Liberatori, S., Gallotta, M., Tontini, M., Tani, C., Speziale, P., Grandi, G. & Margarit, I. (2010). FASEB J. 24, 2839–2848. [DOI] [PubMed]