The C-terminal RNA recognition motif of human ETR-3 protein involved in myotonic dystrophy was over-expressed, purified and crystallized. The crystals obtained diffracted X-rays to 3 Å resolution and belonged to space group P213.

Keywords: human ELAV-type RNA-binding protein 3, ETR-3, C-terminal RNA recognition motif, RRM-3

Abstract

Human embryonically lethal abnormal vision (ELAV)-type RNA-binding protein 3 (ETR-3) has been implicated in many aspects of RNA-processing events including alternative splicing, stability, editing and translation. RNA recognition motif 3 (RRM-3) is an independent C-terminal RNA-binding domain of ETR-3 that preferentially binds to UG-rich repeats of the nuclear or cytoplasmic pre-mRNA, and along with the other domains mediates the inclusion of cardiac troponin T (c-TNT) exon 5 in embryonic muscle, which is otherwise excluded in the adult. In the present study, RRM-3 was cloned, overexpressed, purified and crystallized by the hanging-drop vapour-diffusion method. The crystals diffracted to 3 Å resolution at the home source and belonged to space group P213, with unit-cell parameters a = b = c = 118.5 Å, α = β = γ = 90°. There were two molecules of RRM-3 in the asymmetric unit and the calculated Matthews coefficient (V M) was 6.35 Å3 Da−1, with a solvent content of 80.62%. Initial phases were determined by molecular replacement.

1. Introduction

Alternative splicing is a normal process in eukaryotes, where the exons of pre-mRNA are reconnected in multiple ways. The different mRNAs thus generated are translated into different protein isoforms. This greatly increases the diversity of proteins coded by the genome. In humans about 35–59% of genes are alternatively spliced (Modrek & Lee, 2002 ▶) and this explains the vast repertoire of proteins that are coded from a much smaller number of genes. Changes in the spliceosome machinery, point mutations at the splice sites or the regulatory sites may lead to mis-splicing or differences in splicing of a single gene, thus producing aberrant mRNAs and proteins that are often associated with disease conditions.

The elav gene is required for normal neuronal development of Drosophila melanogaster and mutations in the gene lead to abnormal vision (Campos et al., 1985 ▶; Jiménez & Campos-Ortega, 1987 ▶). ETR-3 [embryonically lethal abnormal vision (ELAV)-type RNA-binding protein 3] is a part of the CUG-BP and ETR-like factors (CELF)/BRUNOL family of proteins (Barreau et al., 2006 ▶) and all of the members of this family share a common architecture of two consecutive N-terminal RRMs (RNA recognition motifs), a divergent domain and a C-terminal RRM. CELF proteins are known to regulate mRNA-processing events such as alternative splicing, RNA editing, mRNA stability and translation (Ladd et al., 2001 ▶; Mankodi et al., 2002 ▶; Dasgupta & Ladd, 2012 ▶). Human ETR-3 binds to intronic elements called muscle-specific elements (MSEs) of the cardiac troponin T (c-TNT) gene and includes exon-5 in the embryonic skeletal muscle, which is otherwise skipped in the adult. If there is an altered splicing of human c-TNT transcripts, it leads to a neuromuscular disorder called myotonic dystrophy type I (DM1; Philips et al., 1998 ▶) in adults.

ETR-3 has a molecular mass of 54 kDa and consists of three RNA recognition motifs of the RRM/RBD/RNP type (RNA recognition motif/RNA binding domain/ribonucleoprotein) with two consecutive N-terminal RRMs, a C-terminal RRM and a divergent domain of 160–230 residues separating them. Two regions within the RRM called the RNP2 and RNP1 are well conserved, indicating the importance of these regions in recognition of target RNA. It has been shown that ETR-3 has preferential binding activity with UG-rich sequences, in particular UG repeats (Faustino & Cooper, 2005 ▶). High-resolution crystal structures of the C-terminal RRM (RRM-3) and its complex with its cognate RNA would provide atomic snapshots of its base recognition and discrimination mechanism.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cloning of ETR-3 RRM-3 in expression vector

The clones for the gene encoding human ETR-3 were a kind gift from Dr Nicolas Charlet-Berguerand (ICGBMC, University of Strasbourg); they were cloned into a pET28a vector with a hexahistidine tag at the N-terminus. Using the construct as the template the RRM-3 of ETR-3 (Gln398-Tyr490) was PCR-amplified using 5′-CGGCAGCCATATGCAGAAGGAAGGTCCAGAGGG-3′ forward and 5′-GGTGGTGCTCGAGTCAGTAAG-3′ reverse primers (restriction sites are shown in bold). The PCR product was double-digested with NdeI and XhoI and cloned into pET28a expression vector (Novagen) according to standard cloning protocols. The recombinant construct contained an N-terminal hexahistidine tag and a thrombin cleavage site followed by RRM-3. The identity of the clone was confirmed by sequencing.

2.2. Overexpression and purification

The recombinant plasmid was transformed into Escherichia coli strain BL21 (DE3) CodonPlus for protein expression. A single colony was picked up and inoculated in Luria–Bertani (LB) medium containing 50 µg ml−1 kanamycin and incubated in a shaker incubator at 310 K and 175 rev min−1. At sufficient cell density, 1% of the primary inoculum was inoculated into 1 l of LB medium and grown at 310 K and 175 rev min−1. At an OD600 of ∼0.8–0.9, the cells were induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 310 K for 6 h or 298 K for 12 h and 175 rev min−1. The cells were harvested and resuspended in sonication buffer (20 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.5, 1 M NaCl, 10 mM imidazole) containing protease-inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and lysed by sonication. The lysate was centrifuged at 20 000g for 45 min and the supernatant was loaded onto 5 ml pre-equilibrated nickel–nitrilotriacetic acid beads (Ni–NTA Superflow; Qiagen). The beads were washed with five column volumes of sonication buffer and the recombinant protein was eluted using a step gradient of imidazole. Eluates were analyzed on a 15% SDS–PAGE gel. The pure fractions were pooled, buffer exchanged with 50 mM NaCl, 25 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.5 and incubated with thrombin at 295 K for 18 h to remove the hexahistidine tag. Thrombin was removed by passing the mixture through a 5 ml benzamidine column. To assess the homogeneity and purity of the preparation, RRM-3 was passed through a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 75 gel-permeation column (GE Healthcare) pre-equilibrated with 50 mM NaCl, 25 mM phosphate buffer pH 6.2. The area under the symmetrical curve in the chromatogram corresponding to the pure RRM-3 fraction was collected and concentrated to 1 mM in 50 mM NaCl, 25 mM phosphate pH 6.2 using a 3 kDa molecular-weight cutoff centrifugal filter (Millipore). The thrombin-digested ETR-3 RRM-3 protein has the following sequence (an N-terminal Gly-Met-Ser-His-Met followed by the ETR-3 RRM3 specific amino acids): GSHMQKEGPEGANLFIYHLPQEFGDQDILQMFMPFGNVISAKVFIDKQTNLSKCFGFVSYDNPVSAQAAIQAMNGFQIGMKRLKVQLKRSKNDSKPY.

2.3. Crystallization, data collection and processing

RRM-3 was concentrated to 12 mg ml−1 for crystallization. The hanging-drop vapour-diffusion method using commercial screens from Hampton Research was used for initial crystallization screening on a crystallization robot (Mosquito). Hits were obtained in SaltRx screen at 1.8 M ammonium citrate, 0.1 M sodium acetate pH 4.6. Optimization was performed at varying concentrations of the precipitant from 1.2 to 1.8 M and crystals were obtained in most of the conditions. Larger diffraction-quality crystals were obtained using the hanging-drop vapour-diffusion method at 293 K by mixing 1 µl RRM-3 solution and 1 µl well solution (1.6 M ammonium citrate, 0.1 M sodium acetate pH 4.6) and were equilibrated against 500 µl well solution. A single cubic-shaped crystal was flash-cooled under a stream of nitrogen gas at 100 K using Paratone oil as a cryoprotectant. Data sets were collected at 100 K using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54 Å) on a MAR345 image-plate detector mounted on a Rigaku MicroMax 007 rotating-anode X-ray generator operated at 40 kV and 20 mA. A total of 33 frames were collected in 1° oscillation steps with 4 min exposure per frame. The crystal-to-detector distance was set to 300 mm. The images were integrated and scaled using HKL-2000 (Otwinowski & Minor, 1997 ▶). Initial phases were determined by the molecular-replacement (MR) method using the coordinates of Sex-lethal (Sxl) protein of Drosophila melanogaster (PDB entry 1b7f; Handa et al., 1999 ▶), which has 30% sequence identity to the target sequence. Relevant statistics for data collection are summarized in Table 1 ▶.

Table 1. Data-collection and processing statistics.

Values in parentheses are for the outermost resolution shell.

| Space group | P213 |

| Unit-cell parameters (Å, °) | a = b = c = 118.5, α = β = γ = 90 |

| Matthews coefficient (Å3 Da−1) | 6.35 |

| Solvent content (%) | 80.62 |

| Data-collection temperature (K) | 100 |

| Detector | MAR 345 mm image plate |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.5418 |

| Resolution (Å) | 48.44–3.00 (3.11–3.00) |

| Unique reflections | 10792 (767) |

| Multiplicity | 4.0 (3.8) |

| 〈I/σ(I〉 | 10.7 (2.2) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.7 (100) |

| R merge † (%) | 14.7 (62.1) |

| Total No. of reflections | 84371 |

| Overall B factor from Wilson plot (Å2) | 63.5 |

| Mosaicity (°) | 0.65 |

R

merge =

, where I

i(hkl) is the intensity of the ith observation of reflection hkl and is the average intensity of the i observations.

, where I

i(hkl) is the intensity of the ith observation of reflection hkl and is the average intensity of the i observations.

3. Results and discussion

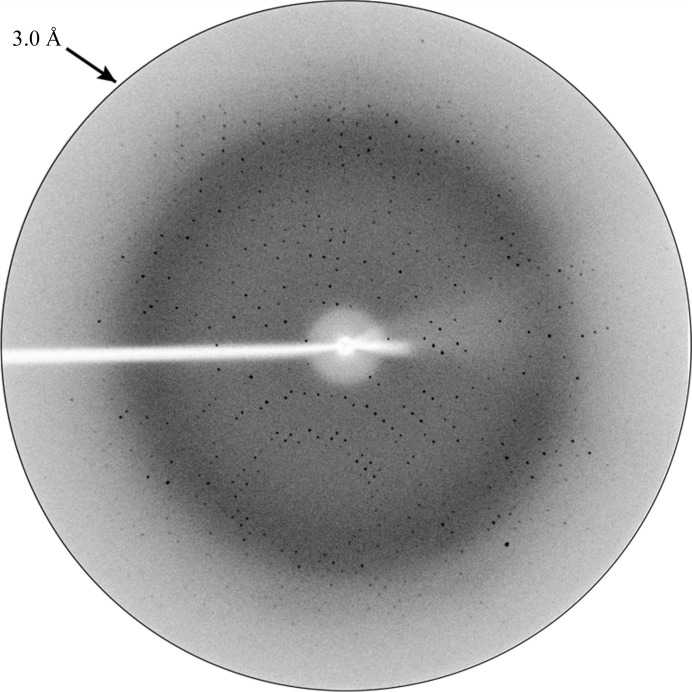

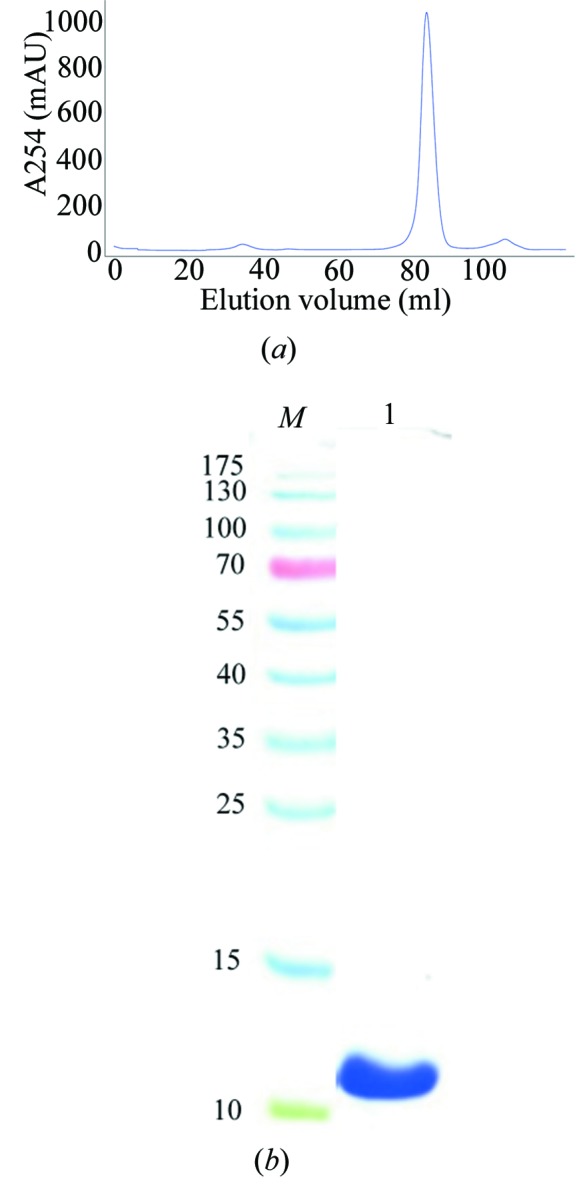

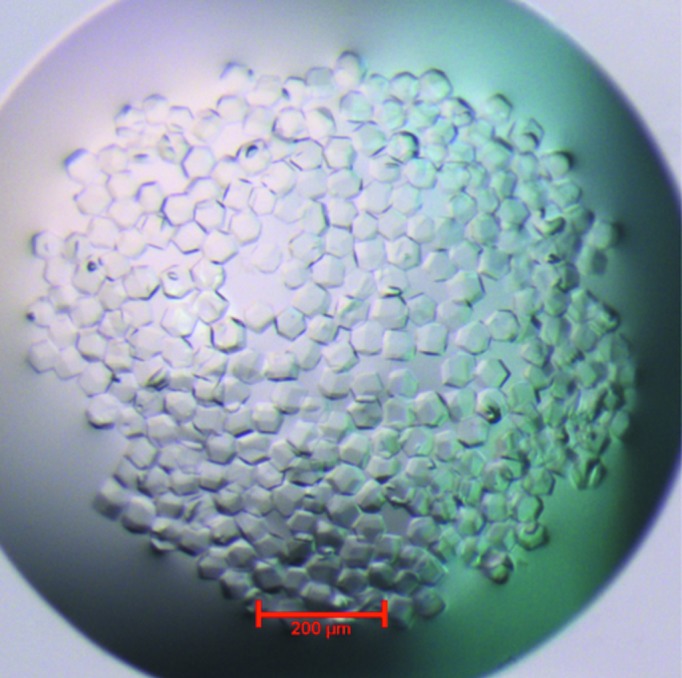

RRM-3 (Gln398-Tyr490) was cloned in pET28a, overexpressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) CodonPlus cells and purified to ∼99% purity using a combination of Ni-affinity and gel-permeation chromatography (Fig. 1 ▶ a). RRM-3 eluted at 80 ml V e from the gel-permeation column, which corresponds to a molecular weight of ∼11 kDa, indicating the monomeric nature of RRM-3 (Fig. 1 ▶ b). The crystals were non-birefringent and a single crystal was used for data collection (Fig. 2 ▶). RRM-3 crystals diffracted to 3.0 Å resolution at the home source (Fig. 3 ▶) and belonged to space group P213, with unit-cell parameters a = b = c = 118.5 Å, α = β = γ = 90°. The unit-cell volume was calculated to be 1 665 397 Å3 with a predicted Matthews coefficient (Matthews, 1968 ▶) of 2.52 Å3 Da−1 and a solvent content of 51%, which corresponds to five RRM-3 molecules (5 × 11 kDa) in the asymmetric unit. However, a possible MR solution was obtained using MOLREP (Vagin & Teplyakov, 2010 ▶), which placed two molecules of RRM-3 in the asymmetric unit with an R factor of 34% and a score of 73%, and the corresponding Matthews coefficient was calculated to be 6.35 Å3 Da−1 with a solvent content of 80.62%. This unusually high solvent content could be explained by the crystal packing, which revealed large solvent cavities with radius of ∼40 Å2. Efforts are under way to build and refine the model.

Figure 1.

Purification of recombinant ETR-3 RRM-3. (a) Superdex 75 gel-permeation chromatography profile of ETR-3 RRM-3 after thrombin cleavage. (b) The area under the major peak analyzed on a 15% SDS–PAGE gel. Lane M, molecular-weight marker (labelled in kDa); lane 1, purified RRM-3 corresponding to ∼11 kDa.

Figure 2.

Morphology of the RRM-3 crystals.

Figure 3.

X-ray diffraction image of a single crystal of ETR-3 RRM-3.

Acknowledgments

The work is funded by the Department of Science and Technology, Government of India under the SERC FAST Track Scheme No. SR/FT/L-011/2009. X-ray diffraction data were collected at the home source at ICGEB, New Delhi. We thank Dr Manickam Yogavel for the use of the X-ray diffraction facility and useful discussion. MK is the recipient of an Indian Council for Medical Research (ICMR) senior research fellowship.

References

- Barreau, C., Paillard, L., Méreau, A. & Osborne, H. B. (2006). Biochimie, 88, 515–525. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Campos, A. R., Grossman, D. & White, K. (1985). J. Neurogenet. 2, 197–218. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Dasgupta, T. & Ladd, A. N. (2012). Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA, 3, 104–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Faustino, N. A. & Cooper, T. A. (2005). Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 879–887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Handa, N., Nureki, O., Kurimoto, K., Kim, I., Sakamoto, H., Shimura, Y., Muto, Y. & Yokoyama, S. (1999). Nature (London), 398, 579–585. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jiménez, F. & Campos-Ortega, J. A. (1987). J. Neurogenet. 4, 179–200. [PubMed]

- Ladd, A. N., Charlet, N. & Cooper, T. A. (2001). Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 1285–1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mankodi, A., Takahashi, M. P., Jiang, H., Beck, C. L., Bowers, W. J., Moxley, R. T., Cannon, S. C. & Thornton, C. A. (2002). Mol. Cell, 10, 35–44. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Matthews, B. W. (1968). J. Mol. Biol. 33, 491–497. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Modrek, B. & Lee, C. (2002). Nature Genet. 30, 13–19. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Otwinowski, Z. & Minor, W. (1997). Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Philips, A. V., Timchenko, L. T. & Cooper, T. A. (1998). Science, 280, 737–741. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Vagin, A. & Teplyakov, A. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 22–25. [DOI] [PubMed]