Abstract

We undertook a gene identification and molecular characterization project in a large kindred originally clinically diagnosed with SCA-X1. While presenting with ataxia, this kindred also had some unique peripheral nervous system features. The implicated region on the X chromosome was delineated using haplotyping. Large deletions and duplications were excluded by array comparative genomic hybridization. Exome sequencing was undertaken in two affected subjects. The single identified X chromosome candidate variant was then confirmed to co-segregate appropriately in all affected, carrier and unaffected family members by Sanger sequencing. The variant was confirmed to be novel by comparison with dbSNP, and filtering for a minor allele frequency of <1% in 1000 Genomes project, and was not present in the NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project or a local database at the BCM HGSC. Functional experiments on transfected cells were subsequently undertaken to assess the biological effect of the variant in vitro. The variant identified consisted of a previously unidentified non-synonymous variant, GJB1 p.P58S, in the Connexin 32/Gap Junction Beta 1 gene. Segregation studies with Sanger sequencing confirmed the presence of the variant in all affected individuals and one known carrier, and the absence of the variant in unaffected members. Functional studies confirmed that the p.P58S variant reduced the number and size of gap junction plaques, but the conductance of the gap junctions was unaffected. Two X-linked ataxias have been associated with genetic loci, with the first of these recently characterized at the molecular level. This represents the second kindred with molecular characterization of X-linked ataxia, and is the first instance of a previously unreported GJB1 mutation with a dominant and permanent ataxia phenotype, although different CNS deficits have previously been reported. This pedigree has also been relatively unique in its phenotype due to the presence of central and peripheral neural abnormalities. Other X-linked SCAs with unique features might therefore also potentially represent variable phenotypic expression of other known neurological entities.

INTRODUCTION

The X-linked hereditary ataxias are a genetically heterogeneous group of central nervous system disorders in which the molecular basis of the phenotype has remained elusive. Five different phenotypic descriptions of the disorder exist on OMIM, two of which (SCA-X1 and SCA-X5) are associated with locus descriptions, with recent molecular characterization of one subtype (1) which maps to the locus for SCA-X5. Symptoms have been reported to range from neonatal onset with death in childhood (SCA-X3) (2), to relatively milder forms with onset in early childhood or adolescence, where lifespan is not affected (SCA-X1) (3). Clinical features invariably include ataxia, although some features (such as mental retardation) are unique to specific subtypes.

The application of next-generation sequencing technologies to the diagnosis of Mendelian diseases has revolutionized the field of gene identification, delivering on the promise of personalized medicine (4–6). Exome sequencing can provide a rapid and cost-effective approach to gene discovery in Mendelian disorders, at times providing the correct diagnosis in cases where clinical overlap has resulted in misdiagnosis (7). In many instances, the discovery of causal variants can provide important information about underlying biological networks and pathways, or provide re-classification of a clinical diagnosis.

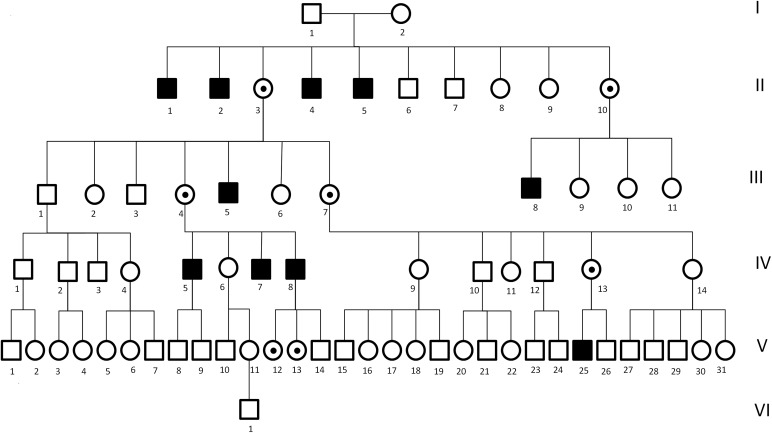

Here, we report on a gene identification project in a well characterized kindred, one of the first two families characterized with SCA-X1 (Fig. 1, pedigree), where detailed clinical features have previously been described (3). The affected family members present primarily with an X-linked hereditary ataxia, with the age of onset in the first or second decade. Intelligence is normal, and anticipation is not observed. Physical examination has previously revealed a mixture of upper and lower motor neuron signs, with only minor phenotypic variability between affected individuals.

Figure 1.

Pedigree.

RESULTS

Clinical findings

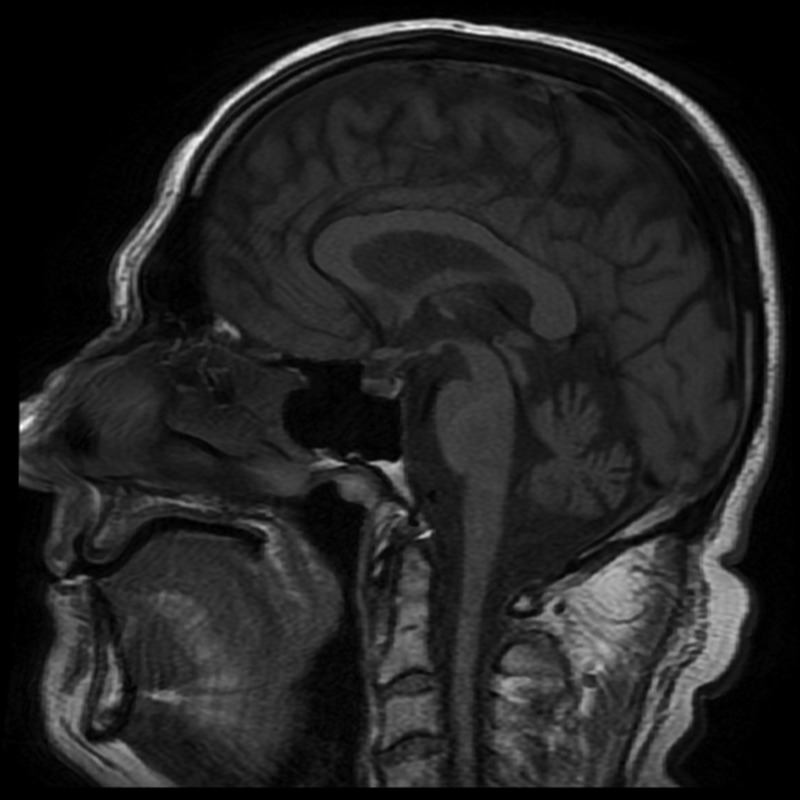

Specific features indicative of cerebellar dysfunction and typical of hereditary ataxias included a presentation with gait and limb ataxia, intention tremor, dysmetria, dysdiadochokinesia, dysarthria, nystagmus and hyperreflexia. Unique phenotypic features included pes cavus in all affected members, scoliosis, muscle atrophy and peripheral sensory and motor nerve abnormalities associated with a reduction in the density of large diameter fibers on sural nerve biopsies. Case V25 (now aged 41) had initially prompted medical referral as he had not walked by age of 2 years and had tended to fall. He had thereafter been unsteady and had poor dexterity. Clinical examination of all four available affected males (IV 5, 7, 8, V25) confirmed a consistent phenotype with cerebellar findings (nystagmus, saccadic pursuit, dysarthria and limb and gait ataxia), pyramidal features (flexor weakness in the legs with brisk knee jerks and upgoing toes) and signs of a sensorimotor neuropathy (distal weakness and wasting with loss of pinprick sensation). An obligate carrier (IV 13) was also examined (age 67). She was asymptomatic but clinical examination showed minor heel–shin ataxia, mild clawing of the toes and absent ankle jerks, despite reinforcement. She had difficulty performing heel–toe gait. EMG/NCS confirmed the presence of a sensorimotor neuropathy. An MRI of the brain and spinal cord, using T1- and T2-weighted and FLAIR sequences on one of the affected individuals (IV-5), showed superior and vermian cerebellar atrophy with diffuse spinal cord atrophy (Fig. 2). These findings were consistent with previously reported postmortem findings, which included extensive loss of cerebellar Purkinje cells, loss of neurons and myelin from the inferior olives and loss of myelin from the spinocerebellar tracts, corticospinal tracts and posterior columns (3).

Figure 2.

T1-weighted sagittal MRI of IV-5, demonstrating atrophy of the cerebellum and spinal cord.

Clinical features for the two pedigree members who underwent exome capture sequencing are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of clinical findings

| Ocular | Saccadic pursuit, gaze-evoked nystagmus |

| Bulbar | Dysarthria |

| Upper limb | Ataxia |

| Lower limbs | Pes cavus |

| Distal weakness and atrophy | |

| Brisk knee jerks | |

| Absent ankle jerks | |

| Upgoing plantar reflexes | |

| Distal sensory loss to pp and JPS | |

| Gait | Ataxic, scissoring |

Findings in both patients were very similar. pp, pinprick sensation; JPS, joint position sense.

Gene identification

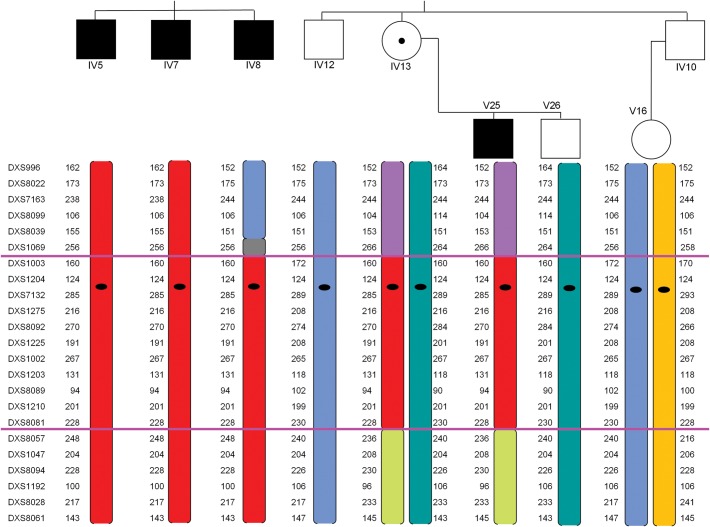

Initial haplotype analysis of available pedigree members delineated the region between DXS 1069 and DXS 8057 as the implicated region on the X chromosome (Fig. 3)—linkage analysis was not formally undertaken. Analysis via oligonucleotide array CGH on one of the affected individuals (IV8) revealed no deletions or duplications on the X chromosome. One deletion copy number variant of 151 kb was identified on 2q, arr 2q37.3(242 505 261–242 656 032) × 1.

Figure 3.

Haplotyping results. Individuals IV5, IV7, IV8, IV12, IV 13, V25 and V26 were available for haplotyping. The region between DXS 1069 and DXS 8057 (between highlighted pink lines) was shared by all affected individuals.

To identify the causative variant, the exomes of two individuals (IV5 and V25) underwent whole-exome capture in solution with subsequent sequencing on two separate platforms for cross-platform validation (SOLiD, Illumina), with a paired-end library (see Materials and Methods). In total, >24 Gb of data were generated and >90% of targeted bases achieved coverage of 20 times or greater. Capture statistics for the X chromosome alone were similar, again showing close to 90% coverage at 20 times or greater, depending on the sequencing platform (Table 2).

Table 2.

Exome capture-sequencing quality statistics for affected subjects IV5 and V25

| Subject | Sequencing platform | Data aligned (Gbp) | Average coverage of whole exome (versus X chromosome only) | Bases 1X + whole exome (versus X chromosome only) | Bases 20X + whole exome (versus X chromosome only) | Bases 40X + whole exome (versus X chromosome only) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IV5 | SOLiD | 11.5 | 131 (113) | 97% (94.4%) | 92% (89%) | 84% (79%) |

| V25 | Illumina | 12.5 | 176 (157) | 99% (99%) | 96% (96%) | 93% (91%) |

In parentheses are capture sequencing quality statistics for Chr X only.

Variant discovery was undertaken with high-sensitivity/low-stringency parameters, with those common to both affected individuals kept (∼273K). Variants were then filtered for minor allele frequency (MAF) by excluding variants present at MAF > 1% in 1000 Genomes project, and not present in the NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project or a local database at the BCM HGSC. Deleteriousness was assessed according to whether variants caused a nonsense, missense, stop loss, frameshift or splicing mutations. Thirty-two variants remained after filtering (Supplementary Material, Table S1). Of these, only one was located on the X chromosome (Table 3).

Table 3.

Discovered variants: number of variants discovered at each stage of the filtering process

| IV5 | V25 | |

|---|---|---|

| All variants | 13 Million | 3.3 Million |

| Shared | 273 735 | |

| Protein changing | 7417 | |

| Rare | 32 | |

| On Chr X | 1 | |

The identified variant was located in the GJB1 gene, mapping to Xq13.1, within the region delineated by haplotyping. This mutation was considered to have a very high likelihood of validity, with ∼230 times total sequence coverage, divided almost evenly between the two sequencing platforms, with both platforms revealing a homozygous C → T substitution at ChrX:70360454 (hg18). This variant (GJB1:c.172 C>T) results in a missense change of proline to serine at p.P58S.

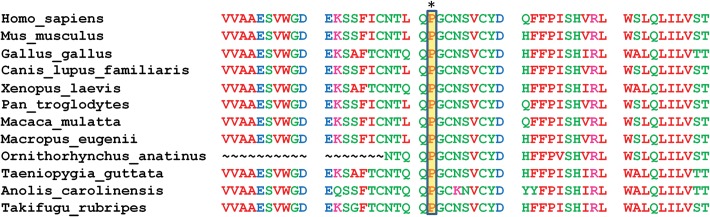

The detected variant was checked by comparison with dbSNP and no MAF information was available, likely indicating it is a very rare allele. Pathogenicity assessment was undertaken by evaluation of amino acid evolutionary conservation and in silico prediction studies. The variant was found to be highly conserved (Fig. 4—Conservation) and was uniformly predicted to have a deleterious effect by LTR-Omega, Phylop, SIFT, Polyphen2, LTR and Mutation Taster.

Figure 4.

Evolutionary conservation using Clustal Omega.

The inheritance pattern of the GJB1 p.P58S mutation was then examined by bidirectional Sanger sequencing. This confirmed the presence of the mutation in all affected individuals (IV5, IV7, IV8 and V25), and also confirmed individual IV13 as a heterozygous carrier, as expected by the pedigree. The absence of the mutation was also confirmed in all available unaffected males (IV12, IV 10 and V26).

Other protein-altering variants in each of the two individuals in whom exome sequencing had been performed were investigated to explore the possibility of epistatic modification of the phenotype conferred by the GJB1 mutation. Neither of the two more common variants identified on the X chromosome was judged plausible modifiers on the basis of their known functions (Supplementary Material, Table S2). A further chromosome 9 variant in a gene known to interact with GJB1 (8) did not segregate with the phenotype in the family.

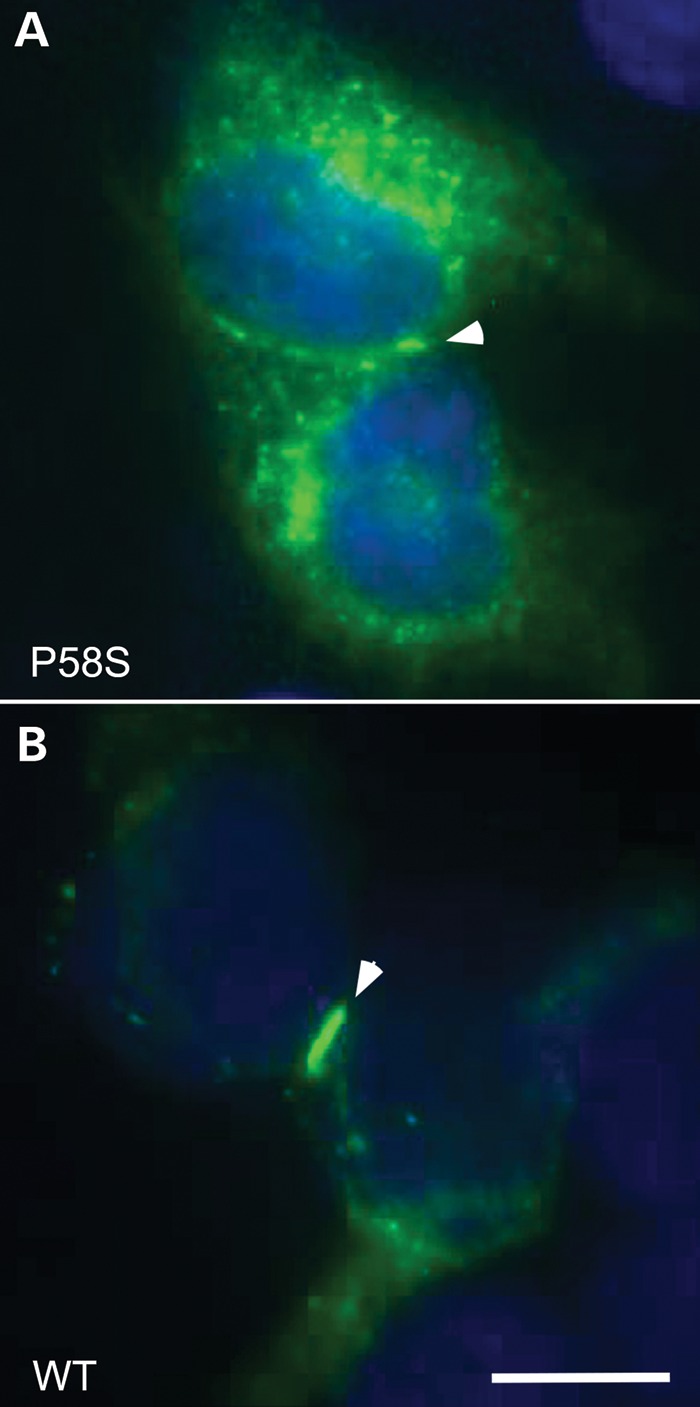

Transfected cell experiments

The p.P58S variant was expressed in communication-deficient HeLa cells by transient transfection, and the cells immunostained with antibodies against Cx32. In cells expressing p.P58S, most of the Cx32-immunoreactivity was localized broadly in the cytoplasm (diffusely and in puncta) with only occasional gap junction plaques at apposing cell borders (Fig. 5A). The cells expressing wild-type (WT) Cx32 also had prominent intracellular Cx32-immunoreactivity, but gap junction plaques were larger and more numerous (Fig. 5B). Intracellular Cx32-immunoreactivity largely co-localized with COP-II (Supplemental Material, Figure), a marker of vesicles that shuttle between the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi.

Figure 5.

These are images of HeLa cells that have been transiently transfected to express p.P58S (A) or WT Cx32 (B). These cells were co-labeled with a mouse antibody against the C-terminus of Cx32 (green) and counterstained with DAPI (blue). The gap junctions are highlighted with arrowheads. Pro58Ser can form gap junction plaques, but these are not as large as seen for WT Cx32. Scale bar: 10 µm.

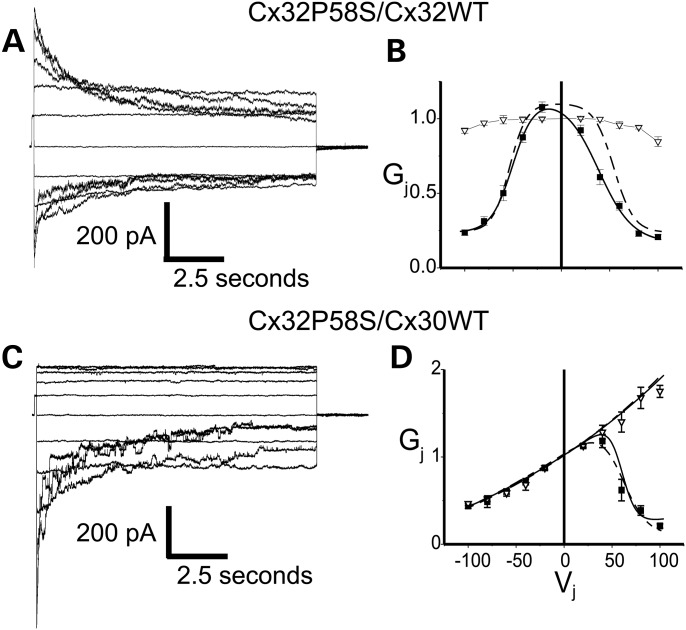

The channel-forming ability of the p.P58S variant was evaluated in Neuro2a cells by measuring electrical coupling between cell pairs with dual whole-cell recordings. These results are summarized in Table 4. When both members of the cell pair expressed either WTCx32 or p.P58S, the cell pairs were well coupled, whereas control pairs expressing EGFP alone showed almost no coupling at all. The studies of functional properties of the variant demonstrated that the junctional currents and normalized Gj−Vj relations for the Cx32P58S/Cx32WT heterotypic pairing showed a modest degree of asymmetry (Fig. 6). The fits for the data from the Cx32P58S/Cx32WT heterotypic channels are shown as a solid line, whereas the fits for data generated from Cx32WT homotypic channels are shown by the dotted line. As can be seen, the two fits are nearly super-imposable at negative voltages, reflecting that both curves represent gating of a WT hemichannel, whereas at positive voltages the fit to the heterotypic data shows a shift to the left, reflecting an increased tendency for the p.P58S hemichannel to close (compared with the WT) when the voltage is made relatively negative in the cell in which it is expressed. These observations are reflected in the fit parameters for the curves, which are shown in Table 5. The shift in open probability for the p.P58S hemichannel had only a small effect on the open probability at Vj = 0. The available morphological data suggest that Cx30 is the predominant heterotypic binding partner of Cx32 in the CNS (7–11). Thus, the properties of the cell–cell channel created by pairing the Cx32P58S variant with Cx30WT were also examined. The findings for the Cx32P58S/Cx30WT heterotypic channel were nearly identical to those for Cx32WT/Cx30WT (Fig. 6C and D, Table 5).

Table 4.

Expression levels between pairs of Neuro2a cells expressing the indicated protein

| EGFP alone | Cx32 WT | Cx32 P58S | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 7 | 4 | 6 |

| Mean | 0.08857 | 28.17 | 51.02 |

| Std deviation | 0.1342 | 38.55 | 47.32 |

| Std error | 0.05073 | 19.28 | 19.32 |

| P-value versus EGFP | P < 0.05 | P < 0.01 |

Figure 6.

Voltage gating of Cx32P58S/Cx32WT and Cx32P58S/Cx30WT channels. (A and C) Representative macroscopic current traces for Cx32P58S/Cx32WT (A) and Cx32P58S/Cx30WT (C) channels. Both cells of a pair were voltage-clamped at the same voltage, then cell 1 (expressing Cx32WT or Cx30WT) was stepped in 20 mV increments from Vj = –100 to Vj = +100 mV, and junctional currents (Ij) were recorded from cell 2 (expressing Cx32P58S). Note that the polarity of Ij is opposite to that of Vj. For Cx32P58S/Cx32WT channels, the rate of current decay increases as the absolute value of Vj increases, with some asymmetry in the kinetics of decay. For Cx32P58S/Cx30WT channels, the rate of Ij decay increased with increasingly positive Vj. For Vj < 40 mV, Ij showed virtually no decay. The Cx32P58S/Cx30WT channels show substantial instantaneous rectification, with at least 3.5-fold greater current at Vj = +100 mV than at −100 mV. Traces were filtered at 500 Hz. Because all traces were normalized to a +20 mV prepulse, amplitudes of the unitary transitions shown in these figures may not accurately reflect the single channel sizes of these channels. (B and D) Average normalized Gj–Vj relations for heterotypic Cx32P58S/Cx32WT (B) and Cx32P58S/Cx30WT (D) channels. The average normalized instantaneous junctional conductance (open triangles) and steady-state (filled squares) junctional conductance (Gj) at each Vj were calculated from the current traces such as those shown in (A) and (C), and fit as described in Materials and Methods. The Cx32P58S/Cx30WT Gj–Vj plot (D) shows instantaneous rectification identical to that described for Cx32/Cx30 channels. Note that rapid gating to closure may have led to underestimates of instantaneous Gj for Cx32/Cx30 channels when the Cx30-cell was stepped to positive voltages, and on both polarities with Cx32P58S/Cx32WTchannels. Solid lines represent fits to Cx32P58S/Cx32WT and Cx32P58S/Cx30WT; broken lines represent fits to data for Cx32WT homotypic and Cx32WT/Cx30WT cell–cell channels.

Table 5.

Boltzmann parameters for fits to the steady state normalized conductances for the noted pairings

| parameter | Cx32P85S/Cx32WT | Cx32 WT homotypic | Cx32P58S/Cx30WT | Cx32WT/Cx30WT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gmax (+V) | 1.08 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.03 |

| Gmin (+V) | 0.16 | 0.22 | 0.16 | 0.10 |

| V0 (+V) | 38.53 | 51.83 | 55.63 | 57.67 |

| A (+V) | 17.57 | 9.78 | 0.137 | 0.077 |

| Gmax (−V) | 1.06 | 1.03 | _ | _ |

| Gmin (−V) | 0.22 | 0.23 | _ | _ |

| −V0 (−V) | −50.42 | −51.06 | _ | _ |

| A (−V) | −0.091 | −0.119 | _ | _ |

For Cx32P58S/Cx30WT and Cx32WT/Cx30WT pairings the steady-state conductances were normalized to the instantaneous ones prior to fitting the data.

DISCUSSION

The family described by Spira et al. (3) was reported as one of the first families with an X-linked spinocerebellar atrophy with a characteristic clinical phenotype, beginning in the first or second decade. Walking was usually delayed with the gradual appearance of ataxia of gait and limb incoordination. There were typical clinical features of both central nervous system dysfunction—cerebellar and pyramidal signs, as well as atypical signs of peripheral nervous disease—a predominantly motor neuropathy with pes cavus. Progression was slow and although often confined to a wheelchair, life expectancy and cognitive function were normal. Post-mortem cerebellar atrophy, which was reported in one of their patients, was also demonstrated on MRI in one of the patients in this study. Although the current clinical findings were consistent with the previous report, we did find evidence of a mild neuropathy and minor clinical signs in an obligate female carrier not previously recognized.

Exome sequencing demonstrated a mutation on the X chromosome within GJB1, which co-segregated with the phenotype in the pedigree. The gap junction proteins are membrane-spanning proteins that assemble into hexamers, with two apposed hexamers forming the gap junction channels. Gap junction channels facilitate the transfer of ions and small molecules between cells, or between layers of the myelin sheath. In the CNS, Cx32 is found primarily in the outer aspects of myelin sheaths of large fibers and at the perikarya of oligodendrocytes (9,10), and to a lesser degree in the myelin of the paranodal region (11). In the peripheral nervous system (PNS), Cx32 is found in the paranodal myelin loops and Schmidt–Lanterman incisures of myelinating Schwann cells (12).

GJB1 is a small gene, with one coding exon (exon2), and three differentially spliced non-coding exons, encoding the well-known gap junction protein Connexin 32/Gap Junction Beta 1 (Cx32). The finding of a GJB1 mutation was unexpected; mutations in GJB1 cause Charcot–Marie–Tooth (CMT) X-linked 1 (13), the second most common form of CMT. CNS phenotypes reported in association with specific GJB1 mutations have been reported (14,15), although these are usually transient or subclinical, and have been classified into three groups: (i) subclinical abnormalities of visual evoked responses and auditory evoked responses; (ii) overt, generally mild fixed abnormalities on neurological examination and/or CNS imaging which may or may not be accompanied by clinical manifestations; and (iii) severe but transient CNS dysfunction resembling acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis and accompanied by white matter changes on MRI (16). The affected patients in our pedigree showed clinical signs of a predominantly motor peripheral neuropathy suggestive of X-linked CMT, although their primary presentation was with fixed ataxia, a hitherto unreported primary presentation.

Approximately 300 mutations have been described for GJB1, with the majority being missense mutations, although nonsense, frameshift, partial and whole-gene deletions have also been reported (17,18). Loss of GJB1 function, including deletion of the GJB1 gene, generally results in the familiar phenotype of neuropathy reported in these patients (19). A different substitution at the same amino acid residue (p.P58R), involving a substitution of proline for arginine rather than serine, reported in a Finnish family with a PNS CMT-X phenotype (20), also resulted in a slightly atypical presentation, with moderate to severe symptoms in both male and (more unusually) female patients; the female proband was diagnosed at age 32 with CMT1 by demonstration of slow motor nerve conduction velocity, pes cavus and hammer toes, with leg and hand muscle weakness and atrophy. Variable phenotypic expressivity associated with different amino acid substitutions at the same codon is not an unusual phenomenon in genetics (21,22), and has previously also been reported in a different member of the gap junction family, GJA1(23).

Gjb1-null mice develop a demyelinating peripheral neuropathy and axonal degeneration (24), with only minor central nervous system myelin abnormalities (25). Similarly, individuals who have a deleted GJB1 gene have not been found to have CNS abnormalities (17,26,27). More florid CNS effects have been restricted to double-knockout mice lacking connexins 32 and 47. It has been suggested that the CNS effects of some Cx32 mutants may be through trans-dominant effects on the expression of other oligodendrocyte expressed connexins such as Cx29 and Cx47 (28,29). Other authors have suggested that a dominant-negative effect of some mutations may disrupt heterotypic gap junctions between oligodendrocytes (O) and astrocytes (A), such as Cx32/Cx30, and may be the cellular mechanism by which GJB1 mutations cause their CNS effects (16,26,30–32). For instance, the asparagine residue (N175) in the second extracellular loop of Cx32 has been demonstrated to be a critical residue for heterotypic gap junction formation (33).

About 70 Cx32 variants associated with CMT1X have been expressed in heterologous cells (Xenopus oocytes or mammalian cell lines). Many of these variants do not reach the cell membrane and fail to form functional gap junction channels (34), instead accumulate in the endoplasmic reticulum and/or Golgi apparatus (35). Those that that do reach the cell membrane generally do not form functionally normal channels (34). In our experiments, the p.P58S variant reduced the number and size of gap junction plaques formed, but the conductance of the gap junctions was unaffected. Thus, loss of functional Cx32 homotypic channels probably does not contribute to the observed CNS effects, though alterations to channel permeability, such as has been demonstrated for several Cx32 variants, cannot be fully excluded by these experiments (36,37). In addition, the p.P58S variant formed heterotypic channels with Cx30WT that differed only minimally from Cx32WT/Cx30WT cell–cell channels, making detrimental effects on heterotypic Cx32/Cx30 pairing unlikely as well. Other possible mechanisms of dysfunction not ruled out by these studies include a trans-dominant effect of p.P58S on other connexins expressed by oligodendrocytes (Cx29 and Cx47), or toxicity induced by the pathologic formation of hemi-channels, as has been described for two other CMT1X mutants (38,39). The possibility that a non-coding sequence variation is influencing the phenotype in this family cannot be excluded by these studies.

The application of exome sequencing to the X-linked SCAs and other previously undiagnosed Mendelian conditions presents a great opportunity to discover their underlying genetic causes. Among the X-linked SCAs, there is considerable phenotypic and genotypic heterogeneity and confused nosology. This pedigree has been unique due to the presence of central and peripheral neural abnormalities. Molecular characterization in X-linked SCAs has identified two loci to date, a novel locus and a novel presentation in a known locus; thus, other X-linked SCAs with unique features might also potentially represent variable phenotypic expression of other known neurological entities, amenable to diagnosis by exome or whole-genome sequencing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Human subjects

Blood samples were obtained and DNA was extracted after obtaining written informed consent from available individuals. Experimental protocols were approved by the South East Sydney Area Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee (ref. 09/142), the Institutional Review Board at the Baylor College of Medicine, and are compliant with the Declaration of Helsinki ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects.

Array comparative genomic hybridization

Comparative genomic hybridization microarray (aCGH) dye-swap analysis was performed using a 60K oligonucleotide (60mer) Human Genome CGH microarray (ISCA design 024612, Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany). Array processing, labeling and hybridization were carried out according to the Agilent protocol. Slides were scanned using an Agilent scanner, data acquired using the Feature Extraction software (v10.5.1.1). Final data analysis was performed using the Agilent Genomic Workbench software (Standard Edition v5.0). A minimum of three consecutive probes were specified for copy number change detection.

Whole-exome capture sequencing

Precapture libraries were generated using 1 µg of DNA as previously described (40). Precapture libraries were hybridized to a custom capture reagent, VCR one probe (41). Capture library quantification and size distribution were analyzed using the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 DNA Chip 7500 (Cat. No. 5067-1506). Capture efficiency was evaluated by performing a qPCR-based SYBER Green assay (Applied Biosystems; Cat. No. 4368708) with built-in controls (RUNX2, PRKG1, SMG1 and NLK). Libraries were either sequenced on a SOLiDv4 or Illumina HiSeq. SOLiD data were aligned to the human genome (hg18) with BFast (42), and Illumina data with BWA (43). Variants were generated with pileup and filtered for quality: read qualities were recalibrated with GATK and a minimum quality score of 30 was required; also, the variant must have been present in at least 15% of the reads which cover the position. In addition, prior to variant calling, reads with low (<11) mapping qualities (a value which is based on the ratio of the best alignment score to the second best alignment score) were removed. This typically eliminates ∼5–10% of the aligned reads. Variants were annotated with AnnoVar (44), and further annotation, segregation and variant filtering were accomplished with in-house tools. Variant discovery was undertaken with high-sensitivity/low-stringency parameters, with variants common to both affected individuals kept (∼273K). Variants were then filtered for MAF by excluding variants present at MAF > 1% in the 1000 Genomes project, and not present in the NHLBI Exome Sequencing Project or a local database at the BCM HGSC.

Sanger sequencing

Sanger sequencing of exon 2 of GJB1 was performed on Genetic Analyzer 3130 (Applied Biosystems), using standard sequencing protocol for PCR-amplified DNA. Primers used for PCR amplification of DNA fragments and Sanger sequencing were as follows:

GJB1 exon 2 forward primer: TGA ATG AGG CAG GAT GAA CT;

GJB1 exon 2 reverse primer: CCT GAG ATG TGG ACC TTG TG.

Transfection and immunostaining

Communication-incompetent HeLa cells (45) were obtained from Dr Klaus Willecke (University of Bonn, Bonn, Germany) and grown in low-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented by 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics (100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin; GIBCO Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37°C. For transient transfection, cells (∼80–90% confluent) were washed with Hank's buffered saline solution, incubated with the combined LTX/Plus/DNA solution in Optimem overnight at 37°C and then fed with DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics. After 2 days, transfected cells were washed in PBS, fixed in acetone at −20°C for 10 min, blocked for 1 h at RT with 5% fish skin gelatin in PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and incubated overnight at 4°C in primary antibodies diluted in the blocking buffer—a mouse monoclonal antibody against the C-terminus (46) of Cx32 (7C6.C7, diluted 1:4; gift of Dr Elliot Herzberg) or a rabbit antiserum against a fusion protein of the intracellular C-terminus (46), combined with a rabbit antiserum against COP-II (ABR Cat. No. PA1–069) or a rat monoclonal antibody against GRP94 (Abcam, Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA, diluted 1:500). After washing in PBS, FITC-conjugated donkey anti-mouse and TRITC-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit or anti-rat antisera (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA; diluted 1:200) were added to the same blocking solution and incubated at RT for 1 h. The slides were washed, counterstained with DAPI, mounted with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA) and imaged with a Leica fluorescence microscope with a Hamamatsu digital camera C4742-95 connected to a G5 Mac computer, using the Openlab 3.1.7 software. Images were manipulated into figures with Photoshop (Adobe).

To evaluate the functional properties of the channels formed by the p.P58S variant, we paired Neuro2a cells expressing the variant with cells expressing Cx32WT or Cx30WT. Because connexin cell–cell channels are formed from two apposed hemichannels (connexins), homotypic channels (those in which both hemichannels are identical) generally produce time-dependent currents that are similar for positive or negative Vj of the same magnitude and have normalized junctional conductance–junctional voltage (Gj–Vj) relations that are symmetric about Vj = 0. On the other hand, heterotypic channels (in which the two apposed hemichannels differ in their properties) will as a rule produce current reflecting different responses to positive or negative Vj of the same magnitude and asymmetric normalized Gj–Vj relations; the degree of asymmetry reflects the degree of difference between the gating and permeability properties of the two hemichannels.

Conductance measurements were made by pulsing from Vj = 0 to ±40 mV. Cytoplasmic bridges were excluded by demonstrating the sensitivity of Gj to the application of bath solution containing octanol. Values for different pairings were compared using the Kruskal–Wallis test with Dunn's multiple comparison test. For the determination of steady-state junctional conductance–junctional voltage (Gj–Vj) relations, cells were held between each pulse at Vj = 0 for 22.5 s, and cell 1 was pulsed in 20 mV increments from −100 to +100 mV for 12.5 s. Any resulting change in current in cell 2, the apposed cell, is attributable to junctional current. Voltage pulses were preceded by a short (∼200 ms) pulse to −20 mV for normalization. Steady-state (t = ∞) conductances were determined by fitting each current trace to a sum of exponentials. Dividing the current at t = ∞ by the applied voltage gives the steady-state junctional conductance. For the determination of Boltzmann parameters, steady-state plots were fit to the product of two Boltzmann distributions of the form: Gss(V) = {Gmin(+) + (Gmax(+) − Gmin(+))/(1 + exp[A(+) (V−Vo(+))])}*{Gmin(−) + (Gmax(−) − Gmin(−))/(1 + exp[A(−) (V−Vo(−))])}.

See Abrams et al. (47) for further details. Homotypic pairs of Cx32WT-IRES-EGFP served as a positive control, and pairs of empty vector expressing cells served as negative controls. Pipette solution: 145 mm CsCl, 5 mm EGTA, 1.4 mm CaCl2, 5.0 mm HEPES, pH 7.2; bath solution: 150 mm NaCl, 4 mmKCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 2 mm CaCl2, 5 mm dextrose, 2 mm pyruvate, 5 mm HEPES, pH 7.4.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

FUNDING

M.N.B. is supported by a PGSD grant from NSERC. This work was also partially funded by the NHGRI (HG003273-9) to R.A.G., the Muscular Dystrophy Association USA (C.K.A.) and the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (to S.S.S.) and NIH (to S.S.S. and C.K.A.).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We acknowledge the support of David and Colleen McIntosh, whose donation prompted this research, and Professor James R. Lupsky and Dr Michael F. Buckley, for critical review and discussion of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zanni G., Cali T., Kalscheuer V.M., Ottolini D., Barresi S., Lebrun N., Montecchi-Palazzi L., Hu H., Chelly J., Bertini E., et al. Mutation of plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase isoform 3 in a family with X-linked congenital cerebellar ataxia impairs Ca2+ homeostasis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 109:14514–14519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207488109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schmidley J.W., Levinsohn M.W., Manetto V. Infantile X-linked ataxia and deafness: a new clinicopathologic entity? Neurology. 1987;37:1344–1349. doi: 10.1212/wnl.37.8.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spira P.J., McLeod J.G., Evans W.A. A spinocerebellar degeneration with X-linked inheritance. Brain. 1979;102:27–41. doi: 10.1093/brain/102.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pierson T.M., Adams D., Bonn F., Martinelli P., Cherukuri P.F., Teer J.K., Hansen N.F., Cruz P., Mullikin J.C. Blakesley R.W., et al., editors. for the NISC Comparative Sequencing Program. Whole-exome sequencing identifies homozygous AFG3L2 mutations in a spastic ataxia-neuropathy syndrome linked to mitochondrial m-AAA proteases. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002325. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bainbridge M.N., Wiszniewski W., Murdock D.R., Friedman J., Gonzaga-Jauregui C., Newsham I., Reid J.G., Fink J.K., Morgan M.B., Gingras M.C., et al. Whole-genome sequencing for optimized patient management. Sci. Trans. Med. 2011;3:87re3. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lupski J.R., Reid J.G., Gonzaga-Jauregui C., Rio Deiros D., Chen D.C., Nazareth L., Bainbridge M., Dinh H., Jing C., Wheeler D.A., et al. Whole-genome sequencing in a patient with Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010;362:1181–1191. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi M., Scholl U.I., Ji W., Liu T., Tikhonova I.R., Zumbo P., Nayir A., Bakkaloglu A., Ozen S., Sanjad S., et al. Genetic diagnosis by whole exome capture and massively parallel DNA sequencing. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:19096–19101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910672106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Szklarczyk D., Franceschini A., Kuhn M., Simonovic M., Roth A., Minguez P., Doerks T., Stark M., Muller J., Bork P., et al. The STRING database in 2011: functional interaction networks of proteins, globally integrated and scored. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D561–D568. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kleopa K.A., Orthmann J.L., Enriquez A., Paul D.L., Scherer S.S. Unique distributions of the gap junction proteins connexin29, connexin32, and connexin47 in oligodendrocytes. Glia. 2004;47:346–357. doi: 10.1002/glia.20043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li X., Ionescu A.V., Lynn B.D., Lu S., Kamasawa N., Morita M., Davidson K.G., Yasumura T., Rash J.E., Nagy J.I. Connexin47, connexin29 and connexin32 co-expression in oligodendrocytes and Cx47 association with zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) in mouse brain. Neuroscience. 2004;126:611–630. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.03.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamasawa N., Sik A., Morita M., Yasumura T., Davidson K.G., Nagy J.I., Rash J.E. Connexin-47 and connexin-32 in gap junctions of oligodendrocyte somata, myelin sheaths, paranodal loops and Schmidt-Lanterman incisures: implications for ionic homeostasis and potassium siphoning. Neuroscience. 2005;136:65–86. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scherer S.S., Deschenes S.M., Xu Y.T., Grinspan J.B., Fischbeck K.H., Paul D.L. Connexin32 is a myelin-related protein in the PNS and CNS. J. Neurosci. 1995;15:8281–8294. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-12-08281.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergoffen J., Scherer S.S., Wang S., Scott M.O., Bone L.J., Paul D.L., Chen K., Lensch M.W., Chance P.F., Fischbeck K.H. Connexin mutations in X-linked Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Science. 1993;262:2039–2042. doi: 10.1126/science.8266101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abrams C.K., Scherer S.S. Gap junctions in inherited human disorders of the central nervous system. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1818:2030–2047. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siskind C., Feely S.M., Bernes S., Shy M.E., Garbern J.Y. Persistent CNS dysfunction in a boy with CMT1X. J. Neurol. Sci. 2009;279:109–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2008.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abrams C.K., Scherer S.S. Gap junctions in inherited human disorders of the central nervous system. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1818:2030–2047. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gonzaga-Jauregui C., Zhang F., Towne C.F., Batish S.D., Lupski J.R. GJB1/Connexin 32 whole gene deletions in patients with X-linked Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Neurogenetics. 2010;11:465–470. doi: 10.1007/s10048-010-0247-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scherer S.S., Wrabetz L. Molecular mechanisms of inherited demyelinating neuropathies. Glia. 2008;56:1578–1589. doi: 10.1002/glia.20751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shy M.E., Siskind C., Swan E.R., Krajewski K.M., Doherty T., Fuerst D.R., Ainsworth P.J., Lewis R.A., Scherer S.S., Hahn A.F. CMT1X phenotypes represent loss of GJB1 gene function. Neurology. 2007;68:849–855. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000256709.08271.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silander K., Meretoja P., Juvonen V., Ignatius J., Pihko H., Saarinen A., Wallden T., Herrgard E., Aula P., Savontaus M.L. Spectrum of mutations in Finnish patients with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease and related neuropathies. Hum. Mutat. 1998;12:59–68. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1998)12:1<59::AID-HUMU9>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Natsuga K., Nishie W., Smith B.J., Shinkuma S., Smith T.A., Parry D.A., Oiso N., Kawada A., Yoneda K., Akiyama M., et al. Consequences of two different amino-acid substitutions at the same codon in KRT14 indicate definitive roles of structural distortion in epidermolysis bullosa simplex pathogenesis. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2011;131:1869–1876. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bradley J.F., Collins D.L., Schimke R.N., Parrott H.N., Rothberg P.G. Two distinct phenotypes caused by two different missense mutations in the same codon of the VHL gene. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1999;87:163–167. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19991119)87:2<163::aid-ajmg7>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pizzuti A., Flex E., Mingarelli R., Salpietro C., Zelante L., Dallapiccola B. A homozygous GJA1 gene mutation causes a Hallermann-Streiff/ODDD spectrum phenotype. Hum. Mutat. 2004;23:286. doi: 10.1002/humu.9220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scherer S.S., Xu Y.T., Nelles E., Fischbeck K., Willecke K., Bone L.J. Connexin32-null mice develop demyelinating peripheral neuropathy. Glia. 1998;24:8–20. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(199809)24:1<8::aid-glia2>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sargiannidou I., Vavlitou N., Aristodemou S., Hadjisavvas A., Kyriacou K., Scherer S.S., Kleopa K.A. Connexin32 mutations cause loss of function in Schwann cells and oligodendrocytes leading to PNS and CNS myelination defects. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:4736–4749. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0325-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takashima H., Nakagawa M., Umehara F., Hirata K., Suehara M., Mayumi H., Yoshishige K., Matsuyama W., Saito M., Jonosono M., et al. Gap junction protein beta 1 (GJB1) mutations and central nervous system symptoms in X-linked Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2003;107:31–37. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2003.01317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hahn A.F., Ainsworth P.J., Naus C.C., Mao J., Bolton C.F. Clinical and pathological observations in men lacking the gap junction protein connexin 32. Muscle Nerve Suppl. 2000;9:S39–S48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kleopa K.A., Yum S.W., Scherer S.S. Cellular mechanisms of connexin32 mutations associated with CNS manifestations. J. Neurosci. Res. 2002;68:522–534. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Altevogt B.M., Kleopa K.A., Postma F.R., Scherer S.S., Paul D.L. Connexin29 is uniquely distributed within myelinating glial cells of the central and peripheral nervous systems. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:6458–6470. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06458.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Omori Y., Mesnil M., Yamasaki H. Connexin 32 mutations from X-linked Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease patients: functional defects and dominant negative effects. Mol. Biol. Cell. 1996;7:907–916. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.6.907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Taylor R.A., Simon E.M., Marks H.G., Scherer S.S. The CNS phenotype of X-linked Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease: more than a peripheral problem. Neurology. 2003;61:1475–1478. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000095960.48964.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kleopa K.A., Zamba-Papanicolaou E., Alevra X., Nicolaou P., Georgiou D.M., Hadjisavvas A., Kyriakides T., Christodoulou K. Phenotypic and cellular expression of two novel connexin32 mutations causing CMT1X. Neurology. 2006;66:396–402. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000196479.93722.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakagawa S., Gong X.Q., Maeda S., Dong Y., Misumi Y., Tsukihara T., Bai D. Asparagine 175 of connexin32 is a critical residue for docking and forming functional heterotypic gap junction channels with connexin26. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;286:19672–19681. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.204958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abrams C.K., Oh S., Ri Y., Bargiello T.A. Mutations in connexin 32: the molecular and biophysical bases for the X-linked form of Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Brain Res. Brain. Res. Rev. 2000;32:203–214. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00082-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yum S.W., Kleopa K.A., Shumas S., Scherer S.S. Diverse trafficking abnormalities of connexin32 mutants causing CMTX. Neurobiol. Dis. 2002;11:43–52. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2002.0545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bicego M., Morassutto S., Hernandez V.H., Morgutti M., Mammano F., D'Andrea P., Bruzzone R. Selective defects in channel permeability associated with Cx32 mutations causing X-linked Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2006;21:607–617. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oh S., Ri Y., Bennett M.V., Trexler E.B., Verselis V.K., Bargiello T.A. Changes in permeability caused by connexin 32 mutations underlie X-linked Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Neuron. 1997;19:927–938. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80973-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abrams C.K., Bennett M.V., Verselis V.K., Bargiello T.A. Voltage opens unopposed gap junction hemichannels formed by a connexin 32 mutant associated with X-linked Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:3980–3984. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261713499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liang G.S., de Miguel M., Gomez-Hernandez J.M., Glass J.D., Scherer S.S., Mintz M., Barrio L.C., Fischbeck K.H. Severe neuropathy with leaky connexin32 hemichannels. Ann. Neurol. 2005;57:749–754. doi: 10.1002/ana.20459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bainbridge M.N., Wang M., Burgess D.L., Kovar C., Rodesch M.J., D'Ascenzo M., Kitzman J., Wu Y.Q., Newsham I., Richmond T.A., et al. Whole exome capture in solution with 3 Gbp of data. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R62. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-6-r62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bainbridge M.N., Wang M., Wu Y., Newsham I., Muzny D.M., Jefferies J.L., Albert T.J., Burgess D.L., Gibbs R.A. Targeted enrichment beyond the consensus coding DNA sequence exome reveals exons with higher variant densities. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R68. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-7-r68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Homer N., Merriman B., Nelson S.F. BFAST: an alignment tool for large scale genome resequencing. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7767. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li H., Durbin R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:589–595. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang K., Li M., Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elfgang C., Eckert R., Lichternberg-Frate H., Butterweck A., Traub O., Klein R.A., Hulser D.F., Willecke K. Specific permeability and selective formation of gap junction channels in connexin-transfected HeLa cells. J. Cell Biol. 1995;129:805–817. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.3.805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahn M., Lee J., Gustafsson A., Enriquez A., Lancaster E., Sul J.Y., Haydon P.G., Paul D.L., Huang Y., Abrams C.K., et al. Cx29 and Cx32, two connexins expressed by myelinating glia, do not interact and are functionally distinct. J. Neurosci. Res. 2008;86:992–1006. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abrams C.K., Islam M., Mahmoud R., Kwon T., Bargiello T.A., Freidin M.M. Functional requirement for a highly conserved charged residue at position 75 in the gap junction protein connexin 32. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:3609–3619. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.392670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.