Abstract

Small GTPases of the Rho family are crucial regulators of actin cytoskeleton rearrangements. Rho is activated by members of the Rho guanine-nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) family; however, mechanisms that regulate RhoGEFs are not well understood. This report demonstrates that PDZ-RhoGEF, a member of a subfamily of RhoGEFs that contain regulator of G protein signaling domains, is partially localized at or near the plasma membranes in 293T, COS-7, and Neuro2a cells, and this localization is coincident with cortical actin. Disruption of the cortical actin cytoskeleton in cells by using latrunculin B prevents the peri-plasma membrane localization of PDZ-RhoGEF. Coimmunoprecipitation and F-actin cosedimentation assays demonstrate that PDZ-RhoGEF binds to actin. Extensive deletion mutagenesis revealed the presence of a novel 25-amino acid sequence in PDZ-RhoGEF, located at amino acids 561–585, that is necessary and sufficient for localization to the actin cytoskeleton and interaction with actin. Last, PDZ-RhoGEF mutants that fail to interact with the actin cytoskeleton display enhanced Rho-dependent signaling compared with wild-type PDZ-RhoGEF. These results identify interaction with the actin cytoskeleton as a novel function for PDZ-RhoGEF, thus implicating actin interaction in organizing PDZ-RhoGEF signaling.

INTRODUCTION

Rho GTPases play fundamental roles in numerous cellular processes that are initiated by extracellular stimuli. A major function of these proteins is to induce changes in the organization of the actin cytoskeleton to promote a variety of cell responses, including morphogenesis, chemotaxis, axonal guidance, and cell cycle progression (Ridley, 2001; Etienne-Manneville and Hall, 2002).

Rho GTPases cycle between an inactive GDP-bound state and an active GTP-bound state. The turning on of this cycle is controlled by a large family of Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factors (RhoGEFs) that stimulate the exchange of GDP for GTP (Zheng, 2001; Hoffman and Cerione, 2002; Schmidt and Hall, 2002). Typically, RhoGEFs are large multidomain proteins that can be subject to a variety of mechanisms to tightly control their function. The common element found in all RhoGEFs is a tandem DH-PH module. The Dbl homology (DH) domain is responsible for the guanine nucleotide exchange activity, and the pleckstrin homology (PH) domain can both direct subcellular localization and modulate DH domain function.

A subfamily of RhoGEFs has been identified by virtue of the presence of a regulator of G protein signaling (RGS) domain (Fukuhara et al., 2001) that directly binds activated, or GTP-bound, heterotrimeric G protein α subunits of the G12 family. In humans, three RGS domain-containing RhoGEFs have been described, namely, p115-RhoGEF, PDZ-RhoGEF, and leukemia-associated RhoGEF (LARG). They share in common the ability to bind activated α12 and α13 and the specificity of activating RhoA but not the other Rho family GTPases Rac1 and Cdc42 (Hart et al., 1996, 1998; Kozasa et al., 1998; Fukuhara et al., 1999, 2000; Rumenapp et al., 1999; Togashi et al., 2000; Reuther et al., 2001). The best studied member of this subfamily is p115-RhoGEF, and compelling evidence has accumulated in vitro and in vivo that supports a major role for p115-RhoGEF in directly coupling heterotrimeric G proteins to Rho (Hart et al., 1998; Kozasa et al., 1998; Girkontaite et al., 2001). In contrast, the functions of LARG and PDZ-RhoGEF are not as well defined.

LARG and PDZ-RhoGEF, but not p115-RhoGEF, both have an N-terminal PDZ domain, suggesting unique functions compared with p115-RhoGEF. Indeed, several reports recently demonstrated that the N-terminal PDZ domains of PDZ-RhoGEF and LARG bind to plexin-B1, a receptor for Semaphorin 4D that mediates repulsive signals in growth cone guidance (Aurandt et al., 2002; Driessens et al., 2002; Hirotani et al., 2002; Perrot et al., 2002; Swiercz et al., 2002). In addition, the N-terminal PDZ domain of LARG, and likely PDZ-RhoGEF, binds to the C terminus of the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (Taya et al., 2001).

Several characteristics of PDZ-RhoGEF, which is alternatively known as KIAA0380, Arhgef11, or GTRAP48, set it apart from both LARG and p115-RhoGEF. Whereas p115-RhoGEF and LARG are substantially activated by α13 (Hart et al., 1998; Wells et al., 2002; Suzuki et al., 2003), PDZ-RhoGEF displays little or no activation of its Rho exchange activity when combined in vitro with α13 (Hart et al., 2000; Wells et al., 2002). PDZ-RhoGEF is able to induce neurite retraction, and in Swiss 3T3 cells PDZ-RhoGEF promotes cell rounding and increases in cortical actin, whereas p115-RhoGEF induces actin stress fibers but not cortical actin reorganization and cell rounding (Togashi et al., 2000). Additionally, only GTRAP48, the rat homolog of PDZ-RhoGEF, has been shown to directly bind the glutamate transporter EAAT4. This interaction, mediated by the C terminus of GTRAP48, is important for the glutamate uptake activity of EAAT4 (Jackson et al., 2001).

Little is known regarding the subcellular localization of PDZ-RhoGEF, although several recent reports indicate that PDZ-RhoGEF is found at or near the plasma membrane (PM) (Rumenapp et al., 1999; Togashi et al., 2000; Hirotani et al., 2002; Swiercz et al., 2002). The studies described in this report were undertaken to determine the subcellular localization of PDZ-RhoGEF and to define the mechanisms responsible. The results obtained demonstrate that PDZ-RhoGEF colocalizes with the actin cytoskeleton in cultured cells and binds to actin complexes in cell lysates. Furthermore, we define a novel, short sequence in PDZ-RhoGEF that is necessary and sufficient for localization at the actin cytoskeleton and interaction with actin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid Construction

KIAA0380 human cDNA was kindly provided by T. Nagase (Kazusa DNA Research Institute, Chiba, Japan). The KIAA0380 coding sequence, hereafter referred to as PDZ-RhoGEF, was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) by using a 5′ primer, 5′ ggcggaattccatggagcagaagctgatctccgaggaggacctgagtgtaaggttaccccag 3′, that introduces an N-terminal Myc epitope tag (EQKLISEEDL), and a 3′ primer, 5′ ggcctcgagttatggtcctggtgacgcggc 3′. It was subcloned into pcDNA3 vector as an EcoRI-XhoI fragment, thus generating the pcDNA3-PDZ-RhoGEF expression plasmid. Similarly, PDZ-RhoGEF-GFP was constructed by amplifying KIAA0380 cDNA with 5′ and 3′ primers, 5′ ggcggaattccatgagtgtaaggttaccc 3′ and 5′ ggccgtcgaccctcctggtcctggtgacgcggctgc 3′, respectively, and then subcloning the resulting full-length cDNA into pEGFP-N1 at the EcoRI and SalI restriction sites.

The N- and C-terminal deletion mutants were all generated by PCR amplification with pcDNA3-PDZ-RhoGEF as a template and subcloning into the EcoRI-XhoI sites of pcDNA3. All deletion mutants were constructed so as to retain an N-terminal Myc epitope tag. The short internal fragments of PDZ-RhoGEF fused to GFP, namely, (541-605)PDZ-RhoGEF-GFP, (551-595)PDZ-RhoGEF-GFP, (561-585)PDZ-RhoGEF-GFP and (496-560)PDZ-RhoGEF-GFP, were generated by PCR amplification with PDZ-RhoGEF-GFP as a template and subcloning into the EcoRI-SalI restriction sites of pEGFP-N1. The internal deletion mutant (Δ25)PDZ-RhoGEF and the alanine mutants K561A/P562A/G563A, N567A/I568A/I569A, Q570A/H571A/F572A, and E573A/N574A/N575A, in which three consecutive amino acids were simultaneously substituted with alanines, were generated by sequential PCR amplification (Ausubel et al., 1992) by using pcDNA3-PDZ-RhoGEF as the template. The products of sequential PCR amplification were subcloned into the EcoRI-XhoI sites of pcDNA3, and they all contained the N-terminal Myc tag. (541-605, Δ25)PDZ-RhoGEF-GFP was generated by PCR amplification by using (Δ25)PDZ-RhoGEF as a template and subcloning into the EcoRI-SalI restriction sites of pEGFP-N1. The correct DNA sequence of the mutants was confirmed by DNA sequencing of the entire open reading frame (Kimmel Cancer Center Nucleic Acid Facility, Philadelphia, PA). The AU1-epitope tagged (DTYRRYI) pCEFL-AU1-LARG was a kind gift from J.S. Gutkind (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). The reporter plasmid that expresses the luciferase gene under the control of serum response element (SRE), termed pSRE-Luc, was purchased from Stratagene (La Jolla, CA). The plasmid carrying the β-galactosidase gene (pCMV-β-gal) was obtained from P. Tsichlis (Tufts University, Boston, MA).

Cell Culture and Transfection

293T, COS-7, and Neuro2a cells were propagated in DMEM containing 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin and streptomycin. Unless otherwise mentioned, cells were plated in six-well plates at 7.0 × 105 cells per well and grown for 24 h before transfection. One microgram of total expression plasmids was transfected into the cells by using FuGENE 6 (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN).

Immunoblotting

Proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The membranes were blocked using 5% milk in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) with 0.05% Tween 20 and were subsequently probed with one of the following primary antibodies: 9E10, anti-Myc at 0.1 μg/ml (Covance, Berkeley, CA), anti-GFP polyclonal antibody (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) at 1:10,000 dilution, or anti-actin monoclonal antibody (mAb) C4 (Chemicon International, Temecula, CA) at 1:10,000 dilution. After incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Promega, Madison, WI), the blots were visualized using Supersignal West Pico (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL).

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

293T or COS-7 cells were grown on coverslips placed in six-well plates and transfected with appropriate plasmids as described in the figure legends. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 15 min and permeabilized by incubation in blocking buffer (2.5% nonfat milk and 1% Triton X-100 in TBS) for 30 min. Neuro2a cells were transfected on poly-d-lysine–coated coverslips. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the media were changed to serum-free DMEM, and 24 h later Neuro2a cells were fixed and permeabilized. Cells were then treated with 1 μg/ml anti-Myc or anti-AU1 mAb (Covance) or a 1:50 dilution of anti-GTRAP48 rabbit polyclonal antibody (a gift from Dr. Jeffrey Rothstein, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD) (Jackson et al., 2001) for 1 h in blocking buffer followed by wash in blocking buffer. Thereafter, the cells were exposed for 45 min to goat anti-mouse antibody labeled with Alexa 488 or 594 or goat anti-rabbit antibody labeled with Alexa 594 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) at a dilution of 1:250. For green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged mutants, incubations with antibodies were omitted. For detection of actin fibers, phalloidin conjugated to Alexa 594 or 647 (Molecular Probes) was used at a dilution of 1:50 or 1:200, respectively. After fixation and incubations with fluorescently tagged antibodies and phalloidin, the coverslips were washed with 1% Triton X-100/TBS, rinsed in distilled water, and mounted on glass slides with 10 μl of Prolong Antifade reagent (Molecular Probes).

Confocal images were acquired using a Bio-Rad MRC-600 laser scanning confocal microscope (Kimmel Cancer Center Bioimaging Facility) running CoMos 7.0 software and interfaced to a Zeiss Plan-Apo 63× 1.40 numerical aperture (NA) oil immersion objective. Dual labeled samples were analyzed using simultaneous excitation at 488 and 568 nm. Images of “x-y” sections through the middle of the cell were recorded. Deconvolved images were acquired using an Olympus BX-61 microscope with a 60× 1.4 NA oil immersion objective and an ORCA-ER (Hamamatsu, Bridgewater, NJ) cooled charge-couple device camera controlled by Slidebook version 4.0 (Intelligent Imaging Innovations, Denver, CO). Image stacks were deconvolved using a constrained iterative algorithm in Slidebook version 4.0. Images of “x-y” planes through the middle of the cell are presented.

PDZ-RhoGEF and mutants were scored for their subcellular distribution pattern based on viewing of numerous images. Cells on coverslips were examined by fluorescence microscopy using an Olympus BX-60 microscope equipped with appropriate filters. For each sample, >100 cells were examined in at least three experiments. Only cells expressing low-to-moderate levels of protein, based on the intensity of the fluorescent signal, were analyzed. The subcellular distribution of PDZ-RhoGEF was used as a comparison for all mutants, and its distribution was scored ++ cytoplasm and ++ plasma membrane. This indicates that a majority of cells showed PDZ-RhoGEF staining equally distributed between diffuse staining in the cytoplasm and sharp staining at or near the cell periphery. Mutants that showed stronger staining at the plasma membrane region with a decrease in cytoplasmic staining compared with wild-type PDZ-RhoGEF were scored as +++ plasma membrane and + cytoplasm. Mutants with no detectable sharp staining at the cell periphery but retaining diffuse staining in the cytoplasm were scored as - plasma membrane and ++ cytoplasm. Mutants scored as + plasma membrane and ++ cytoplasm displayed a weaker and more variable level of plasma membrane staining compared with wild-type PDZ-RhoGEF.

F-Actin Coimmunoprecipitation Assay

COS-7 cells (2.0 × 106) were plated in 6-cm plates and grown for 24 h. The cells were transiently transfected with 3 μg of total expression plasmid by using FuGENE 6. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the cells were replated into 10-cm plates and grown for another 24 h. The cells were then washed twice with cold PBS and lysed using 500 μl of lysis buffer as described previously (Arai et al., 2002). For immunoprecipitation, lysates were incubated with anti-Myc monoclonal or anti-GFP polyclonal antibodies for 3 h at 4°C. The immunocomplexes were recovered with the aid of protein A/G PLUS agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting.

F-Actin Cosedimentation Assays

COS-7 cells (2 × 106) were plated in 6-cm plates and grown for 24 h. The cells were then transfected with 3 μg total of appropriate plasmids as mentioned in the figure legends. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the cells were replated in 10-cm plates and grown for another 24 h. The cells were then washed twice with cold PBS, and the cell lysates were obtained by suspending the cells in 500 μl of lysis buffer containing 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 5 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, and 25 mM β-glycerophosphate and placing the suspension on ice for 45 min. The lysates were then centrifuged at 1500 × g for 5 min at 4°C. The resultant supernatant was then subjected to a high-speed spin at 100,000 × g for 20 min at 4°C. The supernatant thus obtained is the protein preparation used for the cosedimentation assay. F-Actin cosedimentation assay was done essentially as described by the manufacturer (Cytoskeleton, Denver, CO). Briefly, protein preparations were incubated with 40 μg of freshly polymerized actin (F-actin) for 1 h at room temperature. After incubation, the protein plus F-actin solution was subject to high-speed centrifugation (160,000 × g) to pellet F-actin and protein bound to F-actin. The pellet fraction was solubilized in SDS-sample buffer, the volume being equal to the initial incubation volume. Equivalent volumes of pellet and supernatant fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblotting and Coomassie staining.

SRE-mediated Luciferase Gene Transcription Assay

293T cells (7.0 × 105) were plated in six-well plates and grown in 10% serum supplemented DMEM for 24 h. Cells were then switched to serum free DMEM with antibiotics) and were transfected, by using FuGENE 6, with pSRE-Luc (0.1 μg), pCMV-βGal (0.1 μg), pCDNA3, and other plasmids as indicated. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the cells were carefully washed with cold PBS and were lysed using reporter lysis buffer (Promega) as described in the manufacturer's protocol. Five microliters of the lysates was mixed at room temperature with 50 μl of luciferase substrate (Promega), and luciferase activities were determined by measuring luminescence intensity. β-Galactosidase activity of lysates was assayed by the colorimetric method and was used to normalize transfection efficiency. Data were analyzed and plotted using GraphPad Prism. Statistical significance was assessed using an unpaired t test.

Neurite Retraction and Cell Rounding Assay

Neuro2a cells were grown on poly-d-lysine–coated coverslips and transfected using FuGENE6 (Roche Diagnostics) with expression plasmids for GFP, PDZ-RhoGEF, or (Δ25)PDZ-RhoGEF. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the media were changed to serum-free DMEM, and 24 h later Neuro2a cells were fixed, permeabilized, and processed for immunofluorescence as described above. Cells were observed using an Olympus BX-61 microscope with a 60× 1.4 NA oil immersion objective and appropriate filters for GFP or Alexa 594, the latter for detecting cells expressing myc-tagged PDZ-RhoGEF or (Δ25)PDZ-RhoGEF. Cells expressing GFP, PDZ-RhoGEF, or (Δ25)PDZ-RhoGEF were scored as containing neurite extensions, flattened with little or no neurite extensions, or rounded (Togashi et al., 2000). Data were analyzed and plotted using GraphPad Prism. Statistical significance was assessed using an unpaired t test.

RESULTS

Mapping Domain(s) in PDZ-RhoGEF Required for Peri-PM Localization

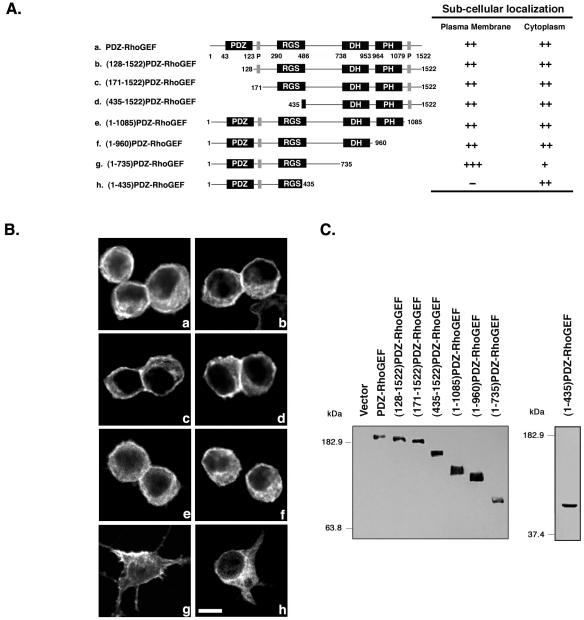

PDZ-RhoGEF, containing an N-terminal Myc epitope tag, was expressed in 293T cells, and its subcellular localization was examined by confocal microscopy. PDZ-RhoGEF exhibited both peri-PM and cytoplasmic localization (Figure 1B, a), consistent with previous observations of transiently expressed PDZ-RhoGEF (Rumenapp et al., 1999; Togashi et al., 2000; Hirotani et al., 2002; Swiercz et al., 2002). The observed PM staining is less sharp (Figure 1B, a) than is often observed for other PM-localized proteins, suggesting the possibility that PDZ-RhoGEF localizes to a region just underneath the PM. Thus, in this report we use the term peri-PM, as used previously (Swiercz et al., 2002), to describe this subcellular distribution pattern. Also, expression of PDZ-RhoGEF in 293T cells caused marked cell rounding consistent with PDZ-RhoGEF-dependent morphological changes observed in other cell types (Togashi et al., 2000). To identify the regions of PDZ-RhoGEF necessary for peri-PM localization, we constructed a series of N- and C-terminal deletions designed to remove known functionally important domains (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Localization of N- and C-terminal deletion mutants of PDZ-RhoGEF. (A) Domain structure of PDZ-RhoGEF is presented (Fukuhara et al., 1999; Longenecker et al., 2001), and the location of the indicated domains and proline-rich regions (P) are shown. N-Terminal and C-terminal deletion mutants of PDZ-RhoGEF are depicted (left), and include full-length PDZ-RhoGEF (a), (128-1522)PDZ-RhoGEF (b), (171-1522)PDZ-RhoGEF (c), (435-1522)PDZ-RhoGEF (d), (1-1085)PDZ-RhoGEF (e), (1-960)PDZ-RhoGEF (f), (1-735)PDZ-RhoGEF (g), and (1-435)PDZ-RhoGEF (h). All constructs have an N-terminal Myc epitope tag. The subcellular localization of these mutants is summarized (right), as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. (B) 293T cells were transiently transfected with expression vectors (1 μg) encoding PDZ-RhoGEF deletion mutants (a–h, as described in A). Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were fixed and processed for immunofluorescence, and images were recorded using confocal microscopy as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. More than 100 cells were examined in at least three separate experiments, and a representative image is shown. Bar, 10 μm. (C) Lysates from cells expressing the indicated PDZ-RhoGEF proteins were immunoblotted with an anti-Myc antibody to compare expression levels.

PDZ domains are involved in protein–protein interactions, typically by binding to the extreme C termini of PM localized receptors. Thus, to test whether PDZ-RhoGEF's PDZ domain mediates the observed peri-PM localization, amino acids 1–127 were deleted to create (128-1522)PDZ-RhoGEF (Figure 1A, b). However, this deletion mutant retained the typical peri-PM and cytoplasmic localization when expressed in 293T cells (Figure 1B, b), indicating that the PDZ domain is not responsible for the observed subcellular localization of the protein. The PDZ domain is followed by a proline-rich sequence from amino acids 149–160 and a RGS domain from amino acids 290–486 (Figure 1A), but deletion of the proline-rich region and most of the RGS domain (Figure 1A, c and d), to create (171-1522)PDZ-RhoGEF and (435-1522)PDZ-RhoGEF, respectively, also failed to change the peri-PM and cytoplasmic localization (Figure 1B, c and d).

In addition to the N-terminal domains, PDZ-RhoGEF has the tandem DH-PH domain, a characteristic feature of all Rho exchange factors, and a C-terminal proline rich sequence from amino acids 1089–1099. A recent report suggested that this C-terminal proline-rich region is important for the peri-PM localization of PDZ-RhoGEF (Togashi et al., 2000). However, when this region was deleted in (1-1085)PDZ-RhoGEF (Figure 1A, e), we still observed the typical partial peri-PM localization (Figure 1B, e). PH domains are found in a number of signaling molecules and often mediate membrane localization by binding to specific membrane lipids or other proteins. However, when we expressed the PH domain deletion mutant (1-960)PDZ-RhoGEF (Figure 1A, f), it retained both peri-PM and cytoplasmic localization (Figure 1B, a), displaying a subcellular localization similar to full-length PDZ-RhoGEF (Figure 1B, f). Likewise, a further C-terminal deletion mutant (1-735)PDZ-RhoGEF (Figure 1A, g), that removes the DH domain, retained peri-PM localization (Figure 1B, g). We note that (1-735)PDZ-RhoGEF lost the ability to induce cell rounding, consistent with the importance of the DH domain to activate Rho and subsequent cytoskeletal rearrangements. Interestingly, (1-735)PDZ-RhoGEF displayed a stronger localization to the cell periphery (Figure 1B, g) compared with full-length PDZ-RhoGEF and other deletion mutants. Finally, we made a larger C-terminal deletion (Figure 1A, h) to additionally remove the region between the RGS and DH domains and found that the localization of (1-435)PDZ-RhoGEF was entirely cytoplasmic (Figure 1B, h). This result suggested that a domain between amino acids 436–735 plays a role in the peri-PM localization of PDZ-RhoGEF, and thus we studied this region in more detail.

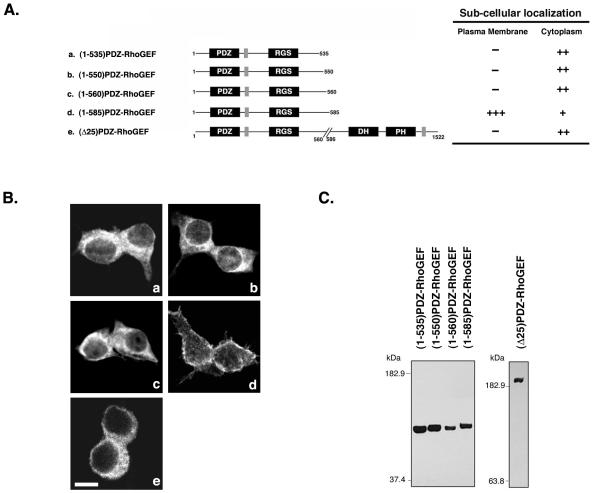

Deletions of residues 536-1522, 551-1522, and 561-1522 (Figure 2A, a–c) resulted in a complete loss of peri-PM localization (Figure 2B, a–c). However, deletion of residues 586-1522 resulted in a predominant peri-PM localization for (1-585)PDZ-RhoGEF (Figure 2B, d). These studies thus indicated the presence of a novel domain between residues 561–585, which contributes to the peri-PM localization of PDZ-RhoGEF. We then made an internal deletion of amino acids 561–585 in full-length PDZ-RhoGEF, and this mutant, termed (Δ25)PDZ-RhoGEF completely lost peri-PM localization (Figure 2B, e), confirming that this 25 amino acid region is necessary for peri-PM localization.

Figure 2.

Role for amino acids 561–585 in localization of PDZ-RhoGEF. (A) Deletion mutants of PDZ-RhoGEF analyzed are depicted (left) and include (1-535)PDZ-RhoGEF (a), (1-550)PDZ-RhoGEF (b), (1-560)PDZ-RhoGEF (c), (1-585)PDZ-RhoGEF (d), and (Δ25)PDZ-RhoGEF (e). All constructs have an N-terminal Myc epitope tag. The subcellular localization of these mutants is summarized (right), as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. (B) 293T cells were transiently transfected with expression vectors (1 μg) encoding PDZ-RhoGEF deletion mutants (a–e, as described in A). Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were fixed and processed for immunofluorescence, and images were recorded using confocal microscopy as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. More than 100 cells were examined in at least three separate experiments, and a representative image is shown. Bar, 10 μm. (C) Lysates from cells expressing the indicated PDZ-RhoGEF proteins were immunoblotted with an anti-Myc antibody to compare expression levels.

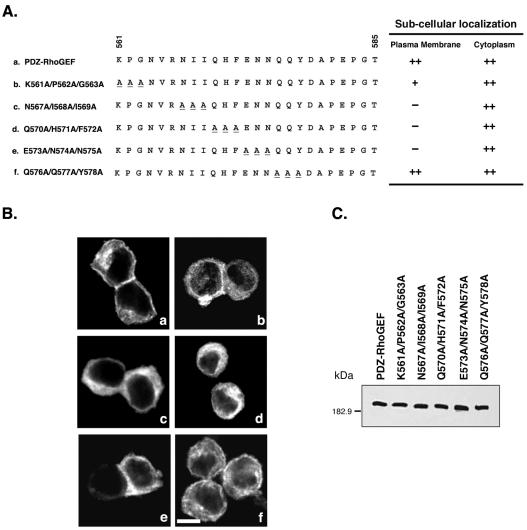

Alanine Scanning Mutagenesis of PDZ-RhoGEF Residues 561–585

To confirm the importance and extend the analysis of this 25-amino acid region in peri-PM localization of PDZ-RhoGEF, we performed alanine scanning mutagenesis of amino acids 561–585, in which three consecutive amino acids each were replaced with alanine (Figure 3A). As described above (Figure 1B, a), PDZ-RhoGEF was localized both in the cytoplasm and PM (Figure 3B, a). Mutant K561A/P562A/G563A (Figure 3A, b) exhibited a reduced peri-PM localization (Figure 3B, b); peri-PM localization seemed weaker compared with wild-type PDZ-RhoGEF. Importantly, mutants N567A/I568A/I569A, Q570A/H571A/F572A, and E573A/N574A/N575A (Figure 3A, c–e) exhibited a complete loss of peri-PM localization (Figure 3B, c–e). The subcellular localization of the mutant Q576A/Q577A/Y578A (Figure 3A, f) was similar to wild-type PDZ-RhoGEF, exhibiting peri-PM as well as cytoplasmic localization (Figure 3B, f). Additional mutants N564A/V565A/R566A, D579A/P581A/E582A, and P583A/G584A/T585A exhibited very poor expression and thus were not analyzed. The other alanine mutants were all expressed at levels comparable with wild-type PDZ-RhoGEF (Figure 3C). From the observations of the alanine mutants, we have identified a stretch of nine amino acids, NIIQHFENN, at positions 567–575 that is critical for peri-PM localization of PDZ-RhoGEF in 293T cells.

Figure 3.

Alanine scanning mutagenesis of amino acids 561–585 in PDZ-RhoGEF. (A) Amino acid sequence between 561 and 585 is depicted for PDZ-RhoGEF (a) and the following triple alanine mutants: K561A/P562A/G563A (b), N567A/I568A/I569A (c), Q570A/H571A/F572A (d), E573A/N574A/N575A (e), and Q576A/Q577A/Y578A (f). The alanine mutations are underlined. All constructs have an N-terminal Myc epitope tag. The subcellular localization of these mutants is summarized (right), as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. (B) 293T cells were transiently transfected with expression vectors (1 μg) encoding full-length PDZ-RhoGEF (a) or the triple alanine mutants (b-f, as described in A). Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were fixed and processed for immunofluorescence, and images were recorded using confocal microscopy as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. More than 100 cells were examined in at least three separate experiments, and a representative image is shown. Bar, 10 μm. (C) Lysates from cells expressing the indicated PDZ-RhoGEF proteins were immunoblotted with an anti-Myc antibody to compare expression levels.

Subcellular Localization of PDZ-RhoGEF in COS-7 Cells

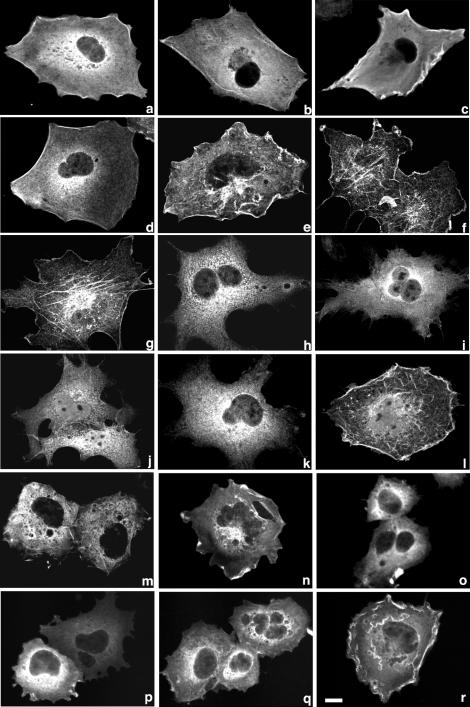

We also examined the subcellular localization of PDZ-RhoGEF and its various mutants in COS-7 cells, a cell type that, in contrast to 293T cells, is more spread out and less susceptible to rounding. From confocal microscopic images, it was observed that full-length PDZ-RhoGEF exhibited both cytoplasmic as well as peri-PM localization when expressed in COS-7 cells (Figure 4a). Similarly, deletions of the PDZ domain, N-terminal proline-rich sequence and RGS domain (Figure 4, b–d) did not alter the subcellular localization of the protein in comparison with full-length PDZ-RhoGEF; they exhibited both peri-PM as well as cytoplasmic localization. Progressive C-terminal deletions of the C-terminal proline-rich region, PH domain, DH domain, and further to amino acid 585, as in (1-1085)PDZ-RhoGEF (Figure 4e), (1-960)PDZ-RhoGEF (Figure 4f), (1-735)PDZ-RhoGEF (Figure 4g), and (1-585)PDZ-RhoGEF (Figure 4l), respectively, did not prevent localization at the periphery of COS-7 cells, as was the case in 293T cells (Figures 1 and 2), and in addition these mutants were observed at intracellular structures (Figure 4, e–g, and l). As described below (Figures 5 and 6), localization at these intracellular structures, as well as at the periphery, likely represents interaction with the actin cytoskeleton. We note that in COS-7 cells expressing full-length PDZ-RhoGEF or constructs containing the intact DH/PH module (e.g., Figure 4, a–d) actin stress fibers are not strongly apparent (our unpublished data; Figures 5b, 6b, and 7d), but deletion mutants that impinge upon the catalytic DH/PH domain do not affect actin stress fibers and thus localization of such mutants to stress fibers is often observed (Figure 4, f, g, and l).

Figure 4.

Subcellular localization of PDZ-RhoGEF and mutants in COS-7 cells. COS-7 cells were transiently transfected with 1 μg of an expression vector encoding Mycepitope–tagged PDZ-RhoGEF (a), (128-1522)PDZ-RhoGEF (b), (171-1522) PDZ-RhoGEF (c), (435-1522)PDZ-RhoGEF (d), (1-1085)PDZ-RhoGEF (e), (1-960)PDZ-RhoGEF (f), (1-735)PDZ-RhoGEF (g), (1-435)PDZ-RhoGEF (h), (1-535) PDZ-RhoGEF (i), (1-550)PDZ-RhoGEF (j), (1-560)PDZ-RhoGEF (k), (1-585)PDZ-RhoGEF (l), (Δ25)PDZ-RhoGEF (m), K561A/P562A/G563A (n), N567A/I568A/I569A (o), Q570A/H571A/F572A (p), E573A/N574A/N575A (q), or Q576A/Q577A/Y578A (r). Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were fixed and processed for immunofluorescence, and images were recorded using confocal microscopy as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. More than 100 cells were examined in at least three separate experiments, and a representative image is shown. Bar, 10 μm.

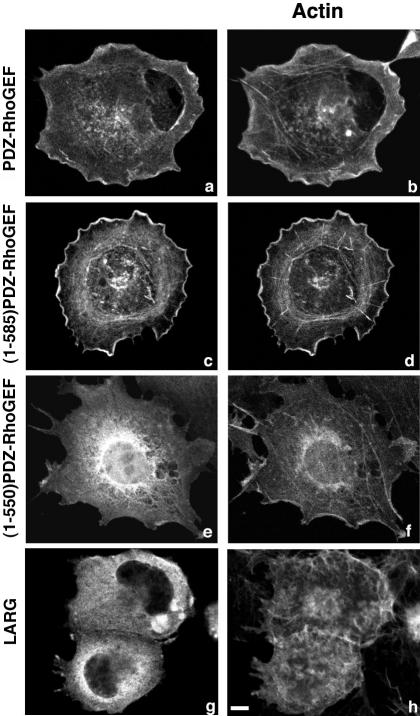

Figure 5.

PDZ-RhoGEF colocalizes with actin. COS-7 cells were transiently transfected with 1 μg of an expression vector encoding Myc-epitope–tagged PDZ-RhoGEF (a and b), (1-585)PDZ-RhoGEF (c and d), (1-550)PDZ-RhoGEF (e and f), or AU1 epitope-tagged LARG (g and h). Expressed proteins were detected with an anti-Myc 9E10 (a, c, and e) or anti-AU1 antibody (g) followed by Alexa 488 conjugated to an anti-mouse antibody. Actin was visualized in the same cells by costaining with Alexa 594 conjugated to phalloidin (b, d, f, and h). Representative images were recorded by confocal microscopy. Bar, 10 μm.

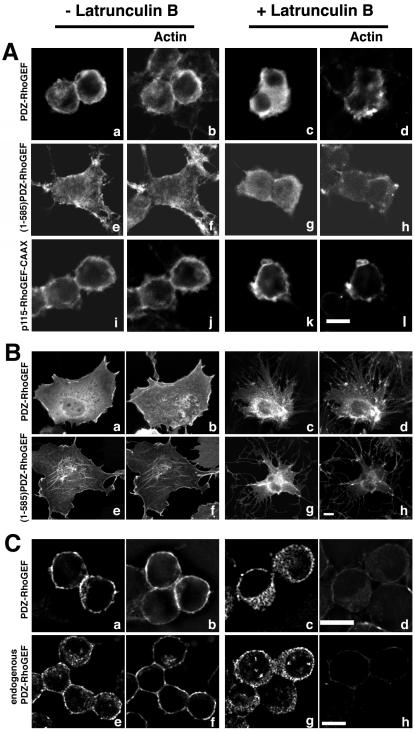

Figure 6.

Latrunculin B treatment disrupts PDZ-RhoGEF localization. (A) 293T cells were transiently transfected with 1 μg of an expression vector encoding Myc-epitope–tagged PDZ-RhoGEF (a–d), (1-585)PDZ-RhoGEF (e–h), or p115-RhoGEF-CAAX (i–l). Before fixation, cells on coverslips were untreated (a, b, e, f, i, and j) or treated (c, d, g, h, k, and l) with 10 μM latrunculin B for 15 min at 37°C. Cells were fixed and dual stained with anti-Myc antibody 9E10 (a, c, e, g, i, and k) followed by an Alexa 488 conjugated secondary antibody and with Alexa 594 conjugated to phalloidin (b, d, f, h, j, and l). Representative images were recorded by confocal microscopy. Bar, 10 μm. (B) COS cells were transiently transfected with 1 μg of an expression vector encoding Myc-epitope–tagged PDZ-RhoGEF (a–d) or (1-585)PDZ-RhoGEF (e–h). Before fixation, cells on coverslips were untreated (a, b, e, and f) or treated (c, d, g, and h) with 10 μM latrunculin B for 15 min at 37°C. Cells were fixed and dual stained with anti-Myc antibody 9E10 (a, c, e, and g) followed by an Alexa 488-conjugated secondary antibody and with Alexa 594 conjugated to phalloidin (b, d, f, and h). Representative images were recorded by confocal microscopy. Bar, 10 μm. (C) Neuro2a cells were transiently transfected with 1 μg of an expression vector encoding Myc-epitope–tagged PDZ-RhoGEF (a–d) or were not transfected (e–h). Before fixation, cells on coverslips were untreated (a, b, e, and f) or treated (c, d, g, and h) with 10 μM latrunculin B for 15 min at 37°C. Cells were fixed and dual stained with anti-Myc antibody 9E10 (a and c) or anti-PDZ-RhoGEF polyclonal antibody (Jackson et al., 2001) (e and g) followed by appropriate Alexa 594-conjugated secondary antibody and with Alexa 647 conjugated to phalloidin (b, d, f, and h). Representative images were recorded by deconvolution microscopy. Bar, 10 μm. Endogenous PDZ-RhoGEF was more readily visualized in rounded Neuro2a cells compared with cells with very flat morphologies.

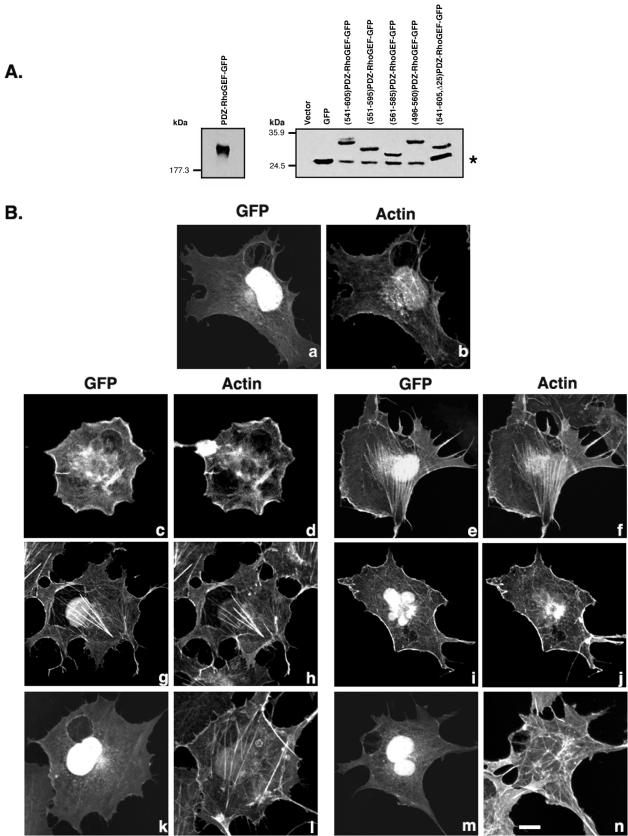

Figure 7.

Amino acids 561–585 of PDZ-RhoGEF are sufficient for colocalization with F-actin. (A) Lysates of cells transfected with 1 μg vector alone or with the indicated expression vector for GFP-tagged forms of PDZ-RhoGEF were subject to Western blotting with an anti-GFP antibody. The asterisk (right) indicates a faster migrating band detected by the anti-GFP antibody and present in all GFP-tagged constructs. This protein comigrates with GFP alone and likely represents degradation or translational initiation from an internal methionine. (B) COS-7 cells were transfected with expression vectors for GFP alone (a and b), full-length PDZRhoGEF-GFP (c and d), (541-605)PDZ-RhoGEF-GFP (e and f), (551-595)PDZ-RhoGEF-GFP (g and h), (561-585)PDZ-RhoGEF-GFP (i and j), (496-560)PDZ-RhoGEF-GFP (k and l), or (541-605, Δ25)PDZ-RhoGEF-GFP (m and n). Twenty-four hours after transfection the cells were fixed and processed for confocal microscopy. Expressed proteins were visualized by GFP fluorescence (a, c, e, g, i, k, and m), and actin was visualized (b, d, f, h, j, l, and n) in the same cells by staining with Alexa 594 conjugated to phalloidin. Bar, 10 μm.

The importance of amino acids 561–585 for subcellular localization of PDZ-RhoGEF was confirmed in COS-7 cells. Similar to the observations in 293T cells (Figures 1 and 2), all PDZ-RhoGEF mutants in which the 561–585 sequence was deleted displayed staining throughout the cytoplasm of COS-7 cells (Figure 4, h–k, and m), with no observable staining at the peri-PM. Furthermore, when key residues within the 561–585 sequence were replaced with alanines, as described in 293T cells (Figure 3A, c–e, and B, c–e), the resulting PDZ-RhoGEF mutants displayed predominant cytoplasmic localization in COS-7 cells (Figure 4, o–q). The mutant K561A/P562A/G563A (Figure 3A, b) displayed relatively weak peri-PM localization (Figure 4n). Mutant Q576A/Q577A/Y578A (Figure 3A, f) displayed staining at the cell periphery (Figure 4r) similar to wild-type, full-length PDZ-RhoGEF. Thus, the results in COS-7 cells agree with the observed localizations in 293T cells and provide further evidence for the importance of amino acids 561–585 of PDZ-RhoGEF in mediating localization to the peri-PM region of cells. Moreover, the confocal microscopy results of COS-7 cells expressing certain PDZ-RhoGEF deletion mutants (Figure 4, f, g, and l) are suggestive of the 561–585 sequence mediating colocalization with the actin cytoskeleton.

PDZ-RhoGEF Colocalizes with Actin and Requires an Intact Actin Cytoskeleton for Localization

A previous report indicated that PDZ-RhoGEF localizes at or near the cortical actin cytoskeleton (Togashi et al., 2000), but the importance of the actin cytoskeleton for the subcellular localization of PDZ-RhoGEF has not been addressed. We stained COS-7 cells with fluorescently labeled phalloidin to directly compare the distribution of F-actin with PDZ-RhoGEF. Full-length PDZ-RhoGEF was seen to colocalize with cortical actin at the cell periphery (Figure 5, a and b). As described above (Figures 2B, d and 4l), (1-585)PDZ-RhoGEF localized predominantly at the peri-PM and to intracellular structures (Figure 5c). When cells expressing this mutant were also stained for actin, it was observed that there was strong colocalization of (1-585)PDZ-RhoGEF with intracellular actin fibers and peripheral actin filaments (Figure 5d). The cytoplasmic (1-550)PDZ-RhoGEF mutant displayed virtually no colocalization with the actin cytoskeleton (Figure 5, e and f). In addition, we examined if the related RGS domain-containing RhoGEF, LARG, colocalized with the actin cytoskeleton. In contrast to PDZ-RhoGEF, LARG seemed to be distributed throughout the cytoplasm and not colocalized with actin (Figure 5, g and h).

We asked whether F-actin was required for the observed peri-PM localization of PDZ-RhoGEF by examining the effect of latrunculin B on localization of PDZ-RhoGEF in several different cell lines. Latrunculins are a class of membrane-permeable compounds that disrupt the actin cytoskeleton by sequestering monomeric actin (Morton et al., 2000). When transfected in 293T cells, PDZ-RhoGEF and (1-585)PDZ-RhoGEF colocalized with actin at the cell periphery (Figure 6A, a, b, e, and f). However, when transfected 293T cells were treated with latrunculin B, full-length PDZ-RhoGEF and (1-585)PDZ-RhoGEF lost their peri-PM localization and displayed an entirely cytoplasmic localization (Figure 6A, c and g). Actin filaments were depolymerized as evident by the decreased intensity of signal and punctate staining pattern of phalloidin (Figure 6A, d and h). We used p115RhoGEF-CAAX, as a control protein that localizes to the PM independent of actin. p115RhoGEF-CAAX was generated by fusing a 20-amino acid CAAX box from H-Ras to the C terminus of p115RhoGEF (Bhattacharyya and Wedegaertner, 2003a). It was observed that p115RhoGEF-CAAX displayed a constitutive PM localization when transiently transfected in 293T cells (Figure 6A, i). When treated with latrunculin B, PM localization of p115RhoGEF-CAAX remained (Figure 6A, k), whereas the actin had depolymerized, as evident by the punctate staining pattern (Figure 6A, l). Thus, latrunculin B treatment does not disrupt localization of all PM-bound proteins, but rather disrupts localization of proteins that require an intact actin cytoskeleton. Similarly, latrunculin B treatment of transfected COS-7 cells affected the subcellular localization of PDZ-RhoGEF and (1-585)PDZ-RhoGEF. Latrunculin B treatment promoted the redistribution of PDZ-RhoGEF and (1-585)PDZ-RhoGEF from the peri-PM and intracellular actin fibers to a perinuclear localization with little or no detectable staining at the cell periphery (Figure 6B, a–h).

Next, we examined the localization of overexpressed and endogenous PDZ-RhoGEF, and the effect of latrunculin B, in a neuronal cell line, Neuro2a. Both overexpressed and endogenous PDZ-RhoGEF displayed the typical partial peri-PM and partial cytoplasmic distribution pattern (Figure 6C, a and e), and the peri-PM localization was coincident with cortical actin (Figure 6C, b and f). Treatment with latrunculin B caused a loss of the peri-PM localization of overexpressed (Figure 6C, c) and endogenous (Figure 6C, g) PDZ-RhoGEF and a redistribution throughout the cytoplasm. As expected, actin staining was greatly reduced in Neuro2a cells after treatment with latrunculin B (Figure 6C, d and h). The results in Figure 6, by using several cell lines and analyzing both overexpressed and endogenous PDZ-RhoGEF, suggest that the peri-PM localization of PDZ-RhoGEF is probably due to interaction with actin.

Amino Acids 561–585 of PDZ-RhoGEF Are Sufficient to Induce Peri-PM/Actin Cytoskeleton Localization of GFP

To further investigate the role of the 25-amino acid region between residues 561 and 585 in colocalization with actin, we made several constructs in which short regions of PDZ-RhoGEF, with or without the 25-amino acid region, were fused to GFP. The expression of the constructs was checked by Western blot analysis by using an anti-GFP antibody (Figure 7A), and their subcellular distribution pattern was examined by confocal microscopy (Figure 7B) after transient expression in COS-7 cells. Although GFP alone was localized throughout the cell (Figure 7B, a), it was seen that, similar to Myc epitope-tagged PDZ-RhoGEF, GFP-tagged full-length PDZ-RhoGEF showed both peri-PM as well as cytoplasmic localization (Figure 7B, c). Furthermore, the peri-PM staining was found to colocalize with actin (Figure 7B, d). Next, we expressed mutants in which relatively short stretches of PDZ-RhoGEF sequence were fused to GFP. (541-605)PDZ-RhoGEF-GFP, (551-595)PDZ-RhoGEF-GFP, and (561-585)PDZ-RhoGEF-GFP, all of which contain the 25-amino acid 561–585 region, colocalize with actin at the cell periphery and with stress fibers (Figure 7B, e–j). However, constructs (496-560)PDZ-RhoGEF-GFP and (541-605, Δ25)PDZ-RhoGEF-GFP, both of which lack the 25-amino acid region, failed to show any prominent peri-PM staining or colocalization with actin (Figure 7B, k–n); the subcellular distribution of (496-560)PDZ-RhoGEF-GFP and (541-605, Δ25)PDZ-RhoGEF-GFP was identical to that of GFP alone. (541-605, Δ25)PDZ-RhoGEF-GFP is a construct in which amino acids 561–585 are internally deleted within the 541–605 sequence. Most GFP fusions, except for full-length PDZ-RhoGEF (Figure 7B, c), also exhibited bright nuclear staining, similar to GFP alone. It is possible that the short 25–65 amino acid regions are inefficiently folded, and thus not all of the fusion protein is targeted to the actin cytoskeleton (Figure 7B, e, g, and i). Alternatively, the nuclear signals may indicate the presence of GFP without the fused PDZ-RhoGEF sequence due to proteolysis or internal methionine initiation. Indeed, Western blots indicate the presence of a band corresponding to GFP alone in all samples (Figure 7A). Nevertheless, the results clearly demonstrate that short regions of PDZ-RhoGEF that contain the crucial 561–585 sequence are sufficient to target a heterologous protein to the peri-PM and actin cytoskeleton (Figure 7B, e–j).

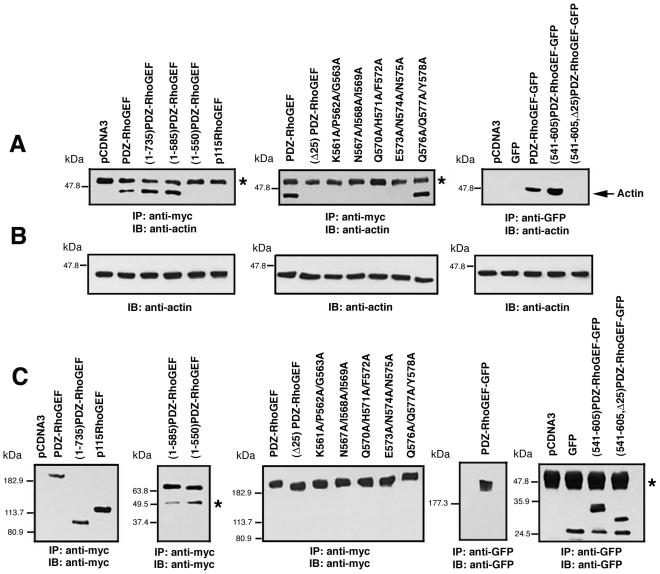

PDZ-RhoGEF Binds to F-Actin

The results obtained so far indicate that the 25-amino acid region between 561 and 585 is important for peri-PM localization of PDZ-RhoGEF, and this 25-amino acid region directs colocalization with actin. Furthermore, the peri-PM localization of PDZ-RhoGEF is completely lost upon treatment with latrunculin B. To test the ability of this 25-amino acid region to bind to actin, coimmunoprecipitation experiments were performed in COS-7 cells transiently transfected with PDZ-RhoGEF or selected mutants. As shown in Figure 8A (left), full-length PDZ-RhoGEF, (1-735)PDZ-RhoGEF, and (1-585)PDZ-RhoGEF were able to coimmunoprecipitate actin; however, (1-550)PDZ-RhoGEF, which lacks the crucial 25-amino acid region, displayed no detectable coimmunoprecipitation of actin (Figure 8A, left). The related RhoGEF, p115-RhoGEF, which is found in the cytoplasm rather than at the peri-PM (Bhattacharyya and Wedegaertner, 2003b), also did not coimmunoprecipitate actin (Figure 8A, left). To further define the importance of the critical 561–585 region, we examined the ability of (Δ25)PDZ-RhoGEF (Figure 2A) or the PDZ-RhoGEF point mutants (Figure 3A) to coimmunoprecipitate with actin (Figure 8A, middle). (Δ25)PDZ-RhoGEF and all the point mutants that show defects in peri-PM localization also fail to coimmunoprecipitate actin; the point mutant Q576A/Q577A/Y578A, which retains localization to the peri-PM, coimmunprecipitates with actin similar to wild-type PDZ-RhoGEF (Figure 8A, middle). Last, GFP fusion proteins were examined (Figure 8A, right). Full-length PDZ-RhoGEF-GFP was able to pull down actin, and, importantly, (541-605)PDZ-RhoGEF-GFP, but not (541-605, Δ25)PDZ-RhoGEF-GFP, was also able to pull down actin (Figure 8A, right), suggesting that the short 561–585 stretch of PDZ-RhoGEF is sufficient for actin interaction. Interestingly, (541-605)PDZ-RhoGEF-GFP, (1-735)PDZ-RhoGEF, and (1-585)PDZ-RhoGEF always showed stronger abilities to pull down actin compared with full-length PDZ-RhoGEF (Figure 8A).

Figure 8.

PDZ-RhoGEF coimmunoprecipitates with actin. (A) COS-7 cells were transiently transfected with 3 μg of an expression vector encoding PDZ-RhoGEF or the indicated mutants with Myc epitope or GFP tags. Myc-tagged p115RhoGEF was used as a control. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with a mouse monoclonal anti-Myc antibody (left and middle) or a polyclonal anti-GFP antibody (right), and immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blot by using anti-actin mAb. (B) Presence of actin in the cell lysates was detected by Western blot by using anti-actin mAb. (C) Immunopreciptation of the Myc-tagged or GFP-tagged PDZ-RhoGEF constructs was confirmed by Western blot of the immunoprecipitates using anti-Myc (left and middle) or anti-GFP (right) antibody. Bands marked (*) represent immunoglobulins precipitated from each immunoprecipitation.

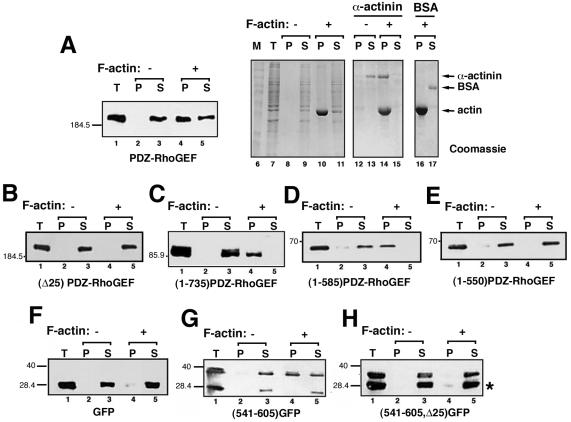

To more directly test the ability of the 25-amino acid region between 561 and 585 of PDZ-RhoGEF to bind to actin, we performed an actin cosedimentation assay. Purified F-actin was added to COS-7 cell lysates, and the ability of PDZ-RhoGEF or its mutants to cosediment with F-actin was examined. Thus, when F-actin is added to a cell lysate and the lysate is then subjected to high-speed centrifugation, the presence of the protein of interest in the pellet fraction indicates binding to F-actin, whereas separation into the soluble fraction indicates no interaction with F-actin. Full-length PDZ-RhoGEF was located exclusively in the soluble fraction in the absence of F-actin (Figure 9A, lane 3). However, in the presence of F-actin, about one-half of the full-length PDZ-RhoGEF protein was located in the F-actin bound pellet fraction (Figure 9A, lane 4). The known actin binding protein α-actinin, used as a positive control, was almost exclusively localized in the F-actin pellet fraction (Figure 9A, lane 14), whereas bovine serum albumin, which was used as a negative control, was localized entirely in the soluble fraction in the presence (Figure 9A, lane 17) or absence (our unpublished data) of F-actin. Actin cosedimentation assays were also performed with cell lysates containing (Δ25)PDZ-RhoGEF, (1-735)PDZ-RhoGEF, (1-585)PDZ-RhoGEF, and (1-550)PDZ-RhoGEF (Figure 9, B–E). Both (1-735)PDZ-RhoGEF and (1-585)PDZ-RhoGEF displayed a strong ability to cosediment with F-actin (Figure 9, C and D, lane 4). On the other hand, both (Δ25)PDZ-RhoGEF and (1-550)PDZ-RhoGEF, which lack the 25-amino acid region, were refractory to cosedimentation with F-actin (Figure 9, B and E, lane 4), consistent with coimmunoprecipitation results (Figure 8). Recovery of protein after a 1-h incubation at room temperature in the presence or absence of F-actin was sometimes variable (e.g., compare Figure 9C, lanes 2 and 3 vs. lanes 4 and 5) and may reflect proteolysis in the cell lysates. Nonetheless, it is clear that full-length PDZ-RhoGEF (Figure 9A) (1-735)PDZ-RhoGEF (Figure 9C), and (1-585)PDZ-RhoGEF (Figure 9D) are all able to cosediment with F-actin.

Figure 9.

PDZ-RhoGEF binds to F-actin. COS-7 cells were transfected with an expression vector for full-length PDZ-RhoGEF (A), (Δ25)PDZ-RhoGEF (B), (1-735)PDZ-RhoGEF (C), (1-585)PDZ-RhoGEF (D), (1-550)PDZ-RhoGEF (E), GFP alone (F), (541-605)PDZ-RhoGEF-GFP (G), or (541-605, Δ25)PDZ-RhoGEF-GFP (H). Cell lysates were prepared, and F-actin cosedimentation assays were performed as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. Lysates were either untreated (lanes 2 and 3) or incubated with F-actin (lanes 4 and 5) and then separated into pellet (P, lanes 2 and 4) and soluble (S, lanes 3 and 5) fractions. Western blots of the P and S fractions (lanes 2–5) along with a sample of the total cell lysates (T) (lane 1) were performed using an anti-Myc (A–E) or anti-GFP (F–H) antibody. The asterisk (*) identifies a faster migrating band detected by the anti-GFP antibody (G and H), and its presence is likely due to degradation or translational initiation from an internal methionine. Note that cosedimentation with F-actin is only observed for the slower migrating species (G, lane 4) that contains the PDZ-RhoGEF 541–605 sequence. Several controls were performed for every F-actin cosedimentation assay, and an example is shown (A, lanes 6–17). An aliquot of the samples corresponding to lanes 1–5 (lanes 7–11) along with marker proteins (lane 6) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Blue to demonstrate sedimentation of F-actin. In addition, purified α-actinin (lanes 12–15) and purified bovine serum albumin (BSA) (lanes 16–17) were incubated without (lanes 12 and 13) or with (lanes 14–17) F-actin, to serve as positive and negative controls, respectively. After sedimentation, these control samples (lanes 12–17) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Blue.

The F-actin cosedimentation assay was also extended to the PDZ-RhoGEF-GFP–tagged constructs. GFP alone was always entirely located in the soluble fraction in the presence or absence of F-actin (Figure 9F, lanes 3 and 5). (541-605)PDZ-RhoGEF-GFP, containing the 25-amino acid region, was localized entirely in the soluble fraction in the absence of F-actin (Figure 9G, lane 3). In the presence of F-actin, nearly one-half the protein was localized in the F-actin bound pellet fraction (Figure 9G, lane 4). However, (541-605, Δ25)PDZ-RhoGEF-GFP, lacking the 25-amino acid region, was always in the soluble fraction regardless of the presence of F-actin (Figure 9H, lanes 3 and 5). F-Actin was always found in the pellet fraction after sedimentation (Figure 9A, lane 10; our unpublished data). Thus, data obtained from actin coimmunoprecipitation and F-actin cosedimentation assays strongly suggest that the region comprising amino acids 561–585 in PDZ-RhoGEF binds to actin.

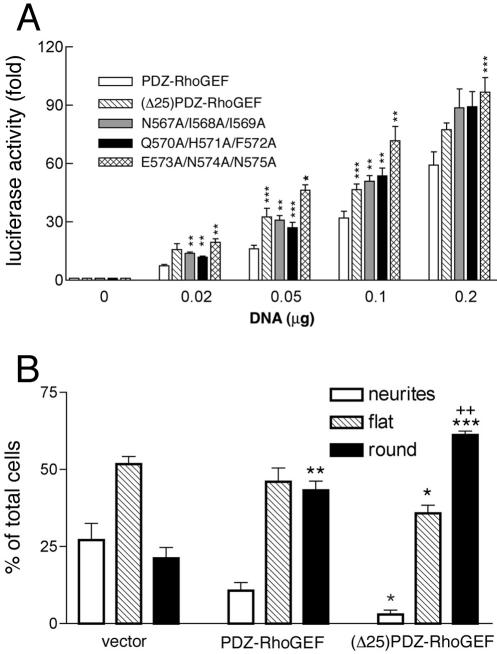

PDZ-RhoGEF Mutants Display Increased Signaling

To test for functional importance of the interaction of PDZ-RhoGEF with the actin cytoskeleton, we compared signaling by PDZ-RhoGEF and PDZ-RhoGEF mutants that failed to colocalize with actin. To avoid any changes in signaling caused by the removal of large protein domains, we only tested alanine mutants (Figure 3A, c–e) or the full-length construct that contained an internal deletion of the 561–585 sequence, (Δ25)PDZ-RhoGEF (Figure 2A, e). The mutants expressed at similar levels compared with wild-type PDZ-RhoGEF (oFigure 3C). As described by others (Fukuhara et al., 1999), PDZ-RhoGEF robustly stimulated Rho-mediated signaling, as measured by a transcriptional reporter assay in which expression of luciferase is under control of an SRE (Figure 10A). Surprisingly, the mutants that do not show any peri-PM localization and colocalization with actin consistently induced higher levels of luciferase activity compared with wild-type PDZ-RhoGEF (Figure 10A). This signaling difference was most pronounced when lower amounts (0.05 or 0.1 μg) of PDZ-RhoGEF constructs were transfected; two- to threefold higher activity by the cytoplasmic mutants was observed. Thus, binding to actin may serve to inhibit the activity of PDZ-RhoGEF.

Figure 10.

Signaling by PDZ-RhoGEF mutants. (A) 293T cells were cotransfected with pSRE, pCMV-βgal, and expression vectors for either PDZ-RhoGEF, (Δ25)PDZ-RhoGEF, N567A/I568A/I569A, Q570A/H571A/F572A, or E573A,N574A,N575A. Cells were transfected with 0.02 to 0.2 μg of the PDZ-RhoGEF mutants, as indicated, and processed for the SRE luciferase assay, as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. The data represent luciferase activity normalized by β-galactosidase activity present in each cellular lysate, expressed as fold induction with respect to control cells, and are the mean ± S.E. of two experiments each performed in duplicate (n = 4). Asterisks indicate statistical difference between the indicated mutant and wild-type PDZ-RhoGEF (*p < 0.0001, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.02). (B) Neuro2a cells on coverslips were transiently transfected with 0.5 μg of an expression vector encoding Myc-epitope tagged PDZ-RhoGEF or (Δ25)PDZ-RhoGEF, or 0.1 μg of pEGFP-N1 (vector). Cells were prepared for immunofluorescence microscopy as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. Expressing cells were scored as containing long extensions (neurites), displaying a flattened morphology (flat), or contracted (round). The data represent the mean ± S.E. for >500 cells from three independent experiments. Asterisks indicate statistical difference between vector alone and wild-type PDZ-RhoGEF or (Δ25)PDZ-RhoGEF–transfected cells (***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.02). Pluses indicate statistical difference between wild-type PDZ-RhoGEF and (Δ25)PDZ-RhoGEF transfected cells (++, p < 0.005).

We next analyzed the ability of PDZ-RhoGEF and the actin-interacting deficient mutant (Δ25)PDZ-RhoGEF to promote neurite retraction and cell rounding in Neuro2a cells. When PDZ-RhoGEF was expressed in Neuro2a cells, fewer cells were observed to have neurite extensions and more cells displayed a strong cell rounding phenotype compared with cells expressing GFP (Figure 10B), in agreement with a recent study (Togashi et al., 2000). Crucially, (Δ25)PDZ-RhoGEF promoted even greater neurite retraction and cell rounding than wild-type PDZ-RhoGEF (Figure 10B). Thus, assaying the effects of PDZ-RhoGEF and (Δ25)PDZ-RhoGEF expression on Neuro2a cell morphology (Figure 10B) agree with the results of the SRE reporter assay (Figure 10A) showing that PDZ-RhoGEF mutants that do not localize at the peri-PM localization and do not interact with actin display increased signaling compared with wild-type PDZ-RhoGEF.

We also compared activation of RhoA in transfected cells by using a well-described GST-RBD pull-down assay, in which GTP-bound RhoA is specifically isolated using the Rho binding domain (RBD) of Rhotekin fused to glutathione S-transferase (GST) (Schwartz et al., 1996; Ren and Schwartz, 2000). In our hands, PDZ-RhoGEF very weakly activates Rho in the pull-down assay, consistent with observations of others (Perrot et al., 2002; Swiercz et al., 2002). In contrast to the SRE-luciferase and neurite retraction assays, we were unable to detect increased RhoA activation by the mutants; PDZ-RhoGEF mutants deficient in peri-PM localization and actin interaction also displayed a low level of Rho activation, similar to wild-type PDZ-RhoGEF, in the GST-RBD pull-down assay (our unpublished data).

DISCUSSION

In this report, we demonstrate that PDZ-RhoGEF colocalizes with the actin cytoskeleton in cells and interacts with F-actin in cell lysates. Importantly, we define a novel sequence in PDZ-RhoGEF that is necessary and sufficient for this interaction. Surprisingly, known protein–protein or protein–lipid interaction domains of PDZ-RhoGEF, such as its PDZ and PH domains, were dispensable for proper subcellular localization and actin interaction, but instead the critical region is contained within a 25-amino acid sequence, residues 561–585, that is located between the RGS and DH domains.

The subcellular localization of expressed PDZ-RhoGEF described in this report is consistent with previous observations in various cell types (Rumenapp et al., 1999; Togashi et al., 2000; Hirotani et al., 2002; Swiercz et al., 2002) where PDZ-RhoGEF localization was detected at or just underneath the PM. Here, extensive deletion mutagenesis identified amino acids 561–585 as an essential sequence that mediates this peri-PM subcellular localization of PDZ-RhoGEF in both 293T and COS-7 cells (Figure 1, 2, 3, 4). Alanine scanning mutagenesis further defined the critical region and indicated that the amino acid sequence NIIQHFENN, consisting of amino acids 567–575, is key in directing subcellular localization of PDZ-RhoGEF (Figures 3 and 4).

In addition to identifying an essential short amino acid sequence, the results presented here suggest a mechanism for the peri-PM localization of PDZ-RhoGEF. The subcellular localization of PDZ-RhoGEF seems to be mediated by interaction with the actin cytoskeleton, and several lines of evidence are consistent with this proposal. First, PDZ-RhoGEF, and all mutants that retain the 561–585 sequence, colocalize with F-actin (Figures 5, 6, 7). Moreover, not only does PDZ-RhoGEF colocalize with cortical actin, as observed in 293T and Neuro2a cells, but the 561–585 sequence also mediates colocalization with actin stress fibers, as observed in COS-7 cells (Figure 7). Consistent with colocalization with F-actin mediated by the 561–585 sequence, an earlier report demonstrated that two PDZ-RhoGEF deletion mutants consisting of amino acids 111-1522 and 92–637 both colocalized with actin in J82 cells, whereas a mutant containing amino acids 637-1522, and thus lacking 561–585, did not (Rumenapp et al., 1999).

Second, the importance of the actin cytoskeleton was extended by our demonstration that the observed localization of PDZ-RhoGEF at the cell periphery in 293T, COS-7, and Neuro2a cells was disrupted by incubation with latrunculin B (Figure 6). Third, when the 561–585 sequence was fused to GFP, fluorescence was strongly observed to colocalize with F-actin (Figure 7), indicating that this crucial 25-amino acid sequence that we have identified in PDZ-RhoGEF is sufficient to target a protein to the actin cytoskeleton. Last, the 561–585 sequence mediated interaction with actin in cell lysates (Figures 8 and 9).

Interaction of actin with PDZ-RhoGEF and mutants containing the 561–585 sequence was demonstrated by the ability of immunoprecipitated PDZ-RhoGEF to pull down actin. Interestingly, C-terminal deletion mutants, such as (1-735)PDZ-RhoGEF and (1-585)PDZ-RhoGEF, were always more effective at coimmunoprecipitating actin (Figure 8A) compared with full-length PDZ-RhoGEF. This raises the possibility that conformational changes in PDZ-RhoGEF may influence the accessibility of the 561–585 domain. Thus, the interaction of PDZ-RhoGEF with the actin cytoskeleton may be regulated in vivo. Interaction with actin was further demonstrated by F-actin cosedimentation assays (Figure 9), in which polymerized actin was directly added to cell lysates containing expressed PDZ-RhoGEF or mutants. The results of the actin coimmunoprecipitation and cosedimentation assays (Figures 8 and 9) are thus consistent with amino acids 561–585 containing an actin binding motif. This sequence seems to be unique and may represent a novel actin binding sequence. Database searches failed to identify other similar sequences, and the 561–585 sequence does not seem to be similar to known actin binding motifs, such as the LKXXES/T motif (Prekeris et al., 1996; Howard et al., 1998) and I/LWEQ module (McCann and Craig, 1997). Alternatively, the binding of PDZ-RhoGEF to actin may be indirect; the 561–585 sequence may bind to an unknown protein that serves as a bridge to link PDZ-RhoGEF to the actin cytoskeleton. In this regard, we have not yet been able to demonstrate actin binding to a purified fragment of PDZ-RhoGEF. A purified GST fusion protein containing amino acids 541–605 of PDZ-RhoGEF shows no significant binding to purified F-actin (our unpublished data); it is unclear whether this apparent lack of direct binding to actin is due to a failure of the actin binding region to fold properly when expressed in bacteria or whether it indicates that additional cellular proteins are required for the formation of a PDZ-RhoGEF/actin complex. Current efforts are directed toward identifying additional proteins that exist in a complex with PDZ-RhoGEF and actin.

Interaction of PDZ-RhoGEF with the actin cytoskeleton seems to be unique among the family of RGS domain-containing RhoGEFs. A sequence similar to 561–585 of PDZ-RhoGEF is not found in p115-RhoGEF or LARG. Moreover, p115-RhoGEF and LARG do not colocalize with F-actin in cultured cells. Endogenous or overexpressed p115-RhoGEF displays a diffuse distribution throughout the cytoplasm (Bhattacharyya and Wedegaertner, 2000, 2003a), and this report demonstrated that p115-RhoGEF does not coimmunoprecipitate with actin (Figure 8A). Likewise, LARG displays a cytoplasmic subcellular localization distinct from PDZ-RhoGEF (Figure 5). A previous report also noted that when expressed in human embryonic kidney 293 cells, PDZ-RhoGEF was localized at the peri-PM, whereas LARG was diffusely localized in the cytoplasm (Hirotani et al., 2002). In contrast, others showed that LARG was localized at the lateral membranes of Madin-Darby canine kidney II cells, and this localization was mediated primarily by its PDZ domain (Taya et al., 2001).

Although p115-RhoGEF and LARG do not bind to the actin cytoskeleton, several other members of the larger family of RhoGEFs have been shown to interact with actin and actin-binding proteins (Schmidt and Hall, 2002). For example, the RhoGEF Trio binds to the actin cross-linking protein filamin (Bellanger et al., 2000). The PH domains of Lbc and Dbl mediate localization to actin stress fibers (Zheng et al., 1996; Olson et al., 1997; Bi et al., 2001); in contrast, the PH domain of PDZ-RhoGEF is not required for its interaction with the actin cytoskeleton. Another RhoGEF, termed frabin, directly binds F-actin through a 150-amino acid N-terminal domain (Obaishi et al., 1998). Although the minimal sequence for actin binding has not been further refined in frabin, a point mutation of leucine to arginine at position 23 was shown to completely disrupt actin binding (Ikeda et al., 2001). Intriguingly, the sequence of amino acids 20–30 of frabin, VSDLISHFEGG, surrounding the critical leucine 23, bears some identity to amino acids 565–575 of PDZ-RhoGEF, VRNIIQHFENN (Figure 3A, a), the core of the 25 amino acid actin-interacting sequence described here. Particularly note-worthy are two hydrophobic residues followed one residue later by the sequence HFE, LISHFE in frabin and IIQHFE in PDZ-RhoGEF. Although speculative at present, further mutational and database analysis will help define this potential actin-binding motif.

A recent report on GTRAP48, which seems to be the rat orthologue of human PDZ-RhoGEF, indicated that it likely exists in a complex with several other proteins, including actin (Jackson et al., 2001). An interaction between GTRAP48 and the glutamate transporter EAAT4 was demonstrated, and an additional interaction between EAAT4 and a protein of unknown function termed GTRAP41 was identified. Although binding of GTRAP48 to actin was not addressed in these studies, it was noted that GTRAP41 contained two α-actinin domains that bind actin. Thus, it was proposed that GTRAP48, GTRAP41, and EAAT4 exist in a plasma membrane localized complex along with actin in neurons (Jackson et al., 2001). The identification of the 561–585 sequence of PDZ-RhoGEF in the present report indicates an additional mechanism for organizing a PDZ-RhoGEF signaling complex.

The basal signaling activity of PDZ-RhoGEF, as measured in transfected cells (Figure 10), does not require localization to the actin cytoskeleton. Surprisingly, PDZ-RhoGEF alanine mutants that do not colocalize with actin were consistently more active in the SRE transcriptional reporter assay (Figure 10A), and likewise, (Δ25)PDZ-RhoGEF was more effective than wild-type PDZ-RhoGEF in promoting neurite retraction and cell rounding of Neuro2a cells (Figure 10B). These results are suggestive of a functional role for actin binding by PDZ-RhoGEF. We can speculate that interaction with the actin cytoskeleton serves to dampen constitutive activation of Rho by PDZ-RhoGEF. Alternatively, actin-binding by PDZ-RhoGEF may serve to localize activation of Rho to discrete subcellular sites and thus initiate a specific subset of Rho signaling pathways. It will be interesting to examine whether activation, for example by plexins or GPCRs, affects PDZ–RhoGEFs interaction with actin or associated proteins. An interesting precedent for cytoskeleton-mediated inhibition of RhoGEF signaling was provided recently by studies on GEF-H1 (Krendel et al., 2002). This RhoGEF binds to microtubules, and disruption of the interaction by deletion mutagenesis or microtubule depolymerization results in increased signaling activity by GEF-H1 (Krendel et al., 2002). Thus, interaction with cytoskeletal elements may be a common mechanism for regulating localization and function of RhoGEFs (Schmidt and Hall, 2002).

In summary, we have identified a novel 25-amino acid sequence of PDZ-RhoGEF. This 561–585 sequence is necessary and sufficient for localization of PDZ-RhoGEF to the actin cytoskeleton and mediates direct binding to actin or actin-associated proteins. Cell signaling by PDZ-RhoGEF is not well understood, and critical protein–protein interactions are just beginning to be identified (Jackson et al., 2001; Aurandt et al., 2002; Driessens et al., 2002; Hirotani et al., 2002; Perrot et al., 2002; Swiercz et al., 2002). This report suggests that interaction with the actin cytoskeleton provides an important mechanism for contributing to the regulation of PDZ-RhoGEF localization and function.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Francesca Santini, Raja Bhattacharyya, and Peter Day for critically reading the manuscript; Dr. Takahiro Nagase for providing the KIAA0380 cDNA; Steven Luke for excellent assistance with confocal microscopy; and Christopher Fischer for preparation of GST fusion proteins. We also thank Drs. Jeffrey Rothstein, Stefan Offermanns, and Koh-ichi Nagata for very generously providing PDZ-RhoGEF antibodies. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM-62884 (to P.W.).

Article published online ahead of print. Mol. Biol. Cell 10.1091/mbc.E03–07–0527. Article and publication date are available at www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E03–07–0527.

References

- Arai, A., Spencer, J.A., and Olson, E.N. (2002). STARS, a striated muscle activator of Rho signaling and serum response factor-dependent transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 24453-24459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aurandt, J., Vikis, H.G., Gutkind, J.S., Ahn, N., and Guan, K.L. (2002). The semaphorin receptor plexin-B1 signals through a direct interaction with the Rho-specific nucleotide exchange factor, LARG. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 12085-12090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel, F.M., Brent, R.E., Kingston, R.E., Moore, D.D., Seidman, J.G., Smith, J.A., and Struhl, K. (1992). Short Protocols in Molecular Biology. John Wiley & Sons: New York.

- Bellanger, J.M., Astier, C., Sardet, C., Ohta, Y., Stossel, T.P., and Debant, A. (2000). The Rac1- and RhoG-specific GEF domain of Trio targets filamin to remodel cytoskeletal actin. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 888-892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya, R., and Wedegaertner, P.B. (2000). Galpha 13 requires palmitoylation for plasma membrane localization, Rho-dependent signaling, and promotion of p115-RhoGEF membrane binding. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 14992-14999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya, R., and Wedegaertner, P.B. (2003a). Characterization of G alpha 13-dependent plasma membrane recruitment of p115RhoGEF. Biochem. J. 371, 709-720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya, R., and Wedegaertner, P.B. (2003b). Mutation of an N-terminal acidic-rich region of p115-RhoGEF dissociates alpha13 binding and alpha13-promoted plasma membrane recruitment. FEBS Lett. 540, 211-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi, F., Debreceni, B., Zhu, K., Salani, B., Eva, A., and Zheng, Y. (2001). Autoinhibition mechanism of proto-Dbl. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 1463-1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driessens, M.H., Olivo, C., Nagata, K., Inagaki, M., and Collard, J.G. (2002). B plexins activate Rho through PDZ-RhoGEF. FEBS Lett. 529, 168-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etienne-Manneville, S., and Hall, A. (2002). Rho GTPases in cell biology. Nature 420, 629-635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuhara, S., Chikumi, H., and Gutkind, J.S. (2000). Leukemia-associated Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor (LARG) links heterotrimeric G proteins of the G(12) family to Rho. FEBS. Lett. 485, 183-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuhara, S., Chikumi, H., and Gutkind, J.S. (2001). RGS-containing RhoGEFs: the missing link between transforming G proteins and Rho? Oncogene 20, 1661-1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuhara, S., Murga, C., Zohar, M., Igishi, T., and Gutkind, J.S. (1999). A novel PDZ domain containing guanine nucleotide exchange factor links heterotrimeric G proteins to Rho. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 5868-5879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girkontaite, I., Missy, K., Sakk, V., Harenberg, A., Tedford, K., Potzel, T., Pfeffer, K., and Fischer, K.D. (2001). Lsc is required for marginal zone B cells, regulation of lymphocyte motility and immune responses. Nat. Immunol. 2, 855-862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart, M.J., Jiang, X., Kozasa, T., Roscoe, W., Singer, W.D., Gilman, A.G., Sternweis, P.C., and Bollag, G. (1998). Direct stimulation of the guanine nucleotide exchange activity of p115 RhoGEF by Galpha13. Science 280, 2112-2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart, M.J., Roscoe, W., and Bollag, G. (2000). Activation of Rho GEF activity by G alpha 13. Methods Enzymol. 325, 61-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart, M.J., Sharma, S., elMasry, N., Qiu, R.G., McCabe, P., Polakis, P., and Bollag, G. (1996). Identification of a novel guanine nucleotide exchange factor for the Rho GTPase. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 25452-25458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirotani, M., Ohoka, Y., Yamamoto, T., Nirasawa, H., Furuyama, T., Kogo, M., Matsuya, T., and Inagaki, S. (2002). Interaction of plexin-B1 with PDZ domain-containing Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factors. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 297, 32-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, G.R., and Cerione, R.A. (2002). Signaling to the Rho GTPases: networking with the DH domain. FEBS Lett. 513, 85-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard, P.L., Klamut, H.J., and Ray, P.N. (1998). Identification of a novel actin binding site within the Dp71 dystrophin isoform. FEBS Lett. 441, 337-341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda, W., Nakanishi, H., Tanaka, Y., Tachibana, K., and Takai, Y. (2001). Cooperation of Cdc42 small G protein-activating and actin filament-binding activities of frabin in microspike formation. Oncogene 20, 3457-3463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, M., Song, W., Liu, M.Y., Jin, L., Dykes-Hoberg, M., Lin, C.I., Bowers, W.J., Federoff, H.J., Sternweis, P.C., and Rothstein, J.D. (2001). Modulation of the neuronal glutamate transporter EAAT4 by two interacting proteins. Nature 410, 89-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozasa, T., Jiang, X., Hart, M.J., Sternweis, P.M., Singer, W.D., Gilman, A.G., Bollag, G., and Sternweis, P.C. (1998). p115 RhoGEF, a GTPase activating protein for Galpha12 and Galpha13. Science 280, 2109-2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krendel, M., Zenke, F.T., and Bokoch, G.M. (2002). Nucleotide exchange factor GEF-H1 mediates cross-talk between microtubules and the actin cytoskeleton. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 294-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longenecker, K.L., Lewis, M.E., Chikumi, H., Gutkind, J.S., and Derewenda, Z.S. (2001). Structure of the RGS-like domain from PDZ-RhoGEF: linking heterotrimeric g protein-coupled signaling to Rho GTPases. Structure 9, 559-569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCann, R.O., and Craig, S.W. (1997). The I/LWEQ module: a conserved sequence that signifies F-actin binding in functionally diverse proteins from yeast to mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 5679-5684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton, W.M., Ayscough, K.R., and McLaughlin, P.J. (2000). Latrunculin alters the actin-monomer subunit interface to prevent polymerization. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 376-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obaishi, H., Nakanishi, H., Mandai, K., Satoh, K., Satoh, A., Takahashi, K., Miyahara, M., Nishioka, H., Takaishi, K., and Takai, Y. (1998). Frabin, a novel FGD1-related actin filament-binding protein capable of changing cell shape and activating c-Jun N-terminal kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 18697-18700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson, M.F., Sterpetti, P., Nagata, K., Toksoz, D., and Hall, A. (1997). Distinct roles for DH and PH domains in the Lbc oncogene. Oncogene 15, 2827-2831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrot, V., Vazquez-Prado, J., and Gutkind, J.S. (2002). Plexin B regulates Rho through the guanine nucleotide exchange factors leukemia-associated Rho GEF (LARG) and PDZ-RhoGEF. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 43115-43120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prekeris, R., Mayhew, M.W., Cooper, J.B., and Terrian, D.M. (1996). Identification and localization of an actin-binding motif that is unique to the epsilon isoform of protein kinase C and participates in the regulation of synaptic function. J. Cell Biol. 132, 77-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren, X.D., and Schwartz, M.A. (2000). Determination of GTP loading on Rho. Methods Enzymol. 325, 264-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuther, G.W., Lambert, Q.T., Booden, M.A., Wennerberg, K., Becknell, B., Marcucci, G., Sondek, J., Caligiuri, M.A., and Der, C.J. (2001). Leukemia-associated Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor, a Dbl family protein found mutated in leukemia, causes transformation by activation of RhoA. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 27145-27151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridley, A.J. (2001). Rho family proteins: coordinating cell responses. Trends Cell Biol. 11, 471-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumenapp, U., Blomquist, A., Schworer, G., Schablowski, H., Psoma, A., and Jakobs, K.H. (1999). Rho-specific binding and guanine nucleotide exchange catalysis by KIAA0380, a Db1 family member. FEBS Lett. 459, 313-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, A., and Hall, A. (2002). Guanine nucleotide exchange factors for Rho GTPases: turning on the switch. Genes Dev. 16, 1587-1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, M.A., Toksoz, D., and Khosravi-Far, R. (1996). Transformation by Rho exchange factor oncogenes is mediated by activation of an integrin-dependent pathway. EMBO J. 15, 6525-6530. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, N., Nakamura, S., Mano, H., and Kozasa, T. (2003). Galpha 12 activates Rho GTPase through tyrosine-phosphorylated leukemia-associated RhoGEF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 733-738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swiercz, J.M., Kuner, R., Behrens, J., and Offermanns, S. (2002). Plexin-B1 directly interacts with PDZ-RhoGEF/LARG to regulate RhoA and growth cone morphology. Neuron 35, 51-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taya, S., Inagaki, N., Sengiku, H., Makino, H., Iwamatsu, A., Urakawa, I., Nagao, K., Kataoka, S., and Kaibuchi, K. (2001). Direct interaction of insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor with leukemia-associated RhoGEF. J. Cell Biol. 155, 809-820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Togashi, H., Nagata, K., Takagishi, M., Saitoh, N., and Inagaki, M. (2000). Functions of a Rho-specific guanine nucleotide exchange factor in neurite retraction—Possible role of a proline-rich motif of KIAA0380 in localization. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 29570-29578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells, C.D., Liu, M.Y., Jackson, M., Gutowski, S., Sternweis, P.M., Rothstein, J.D., Kozasa, T., and Sternweis, P.C. (2002). Mechanisms for reversible regulation between G13 and Rho exchange factors. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 1174-1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y. (2001). Dbl family guanine nucleotide exchange factors. Trends Biochem. Sci. 26, 724-732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y., Zangrilli, D., Cerione, R.A., and Eva, A. (1996). The pleckstrin homology domain mediates transformation by oncogenic dbl through specific intracellular targeting. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 19017-19020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]