Abstract

Rhabditid nematodes are one of a few animal taxa in which androdioecious reproduction, involving hermaphrodites and males, is found. In the genus Pristionchus, several cases of androdioecy are known, including the model species P. pacificus. A comprehensive understanding of the evolution of reproductive mode depends on dense taxon sampling and careful morphological and phylogenetic reconstruction. In this article, two new androdioecious species, P. boliviae n. sp. and P. mayeri n. sp., and one gonochoristic outgroup, P. atlanticus n. sp., are described on morphological, molecular, and biological evidence. Their phylogenetic relationships are inferred from 26 ribosomal protein genes and a partial SSU rRNA gene. Based on current representation, the new androdioecious species are sister taxa, indicating either speciation from an androdioecious ancestor or rapid convergent evolution in closely related species. Male sexual characters distinguish the new species, and new characters for six closely related Pristionchus species are presented. Male papillae are unusually variable in P. boliviae n. sp. and P. mayeri n. sp., consistent with the predictions of “selfing syndrome.” Description and phylogeny of new androdioecious species, supported by fuller outgroup representation, establish new reference points for mechanistic studies in the Pristionchus system by expanding its comparative context.

Keywords: gonochorism, hermaphroditism, morphology, P. boliviae n. sp., P. mayeri n. sp., phylogeny, Pristionchus atlanticus n. sp., selfing syndrome, taxonomy

Androdioecy, a reproductive mode involving both hermaphrodites and males, has been considered an unlikely or rare phenomenon, given the improbable conditions theoretically necessary to give rise to and maintain it (Darwin, 1877; Charlesworth, 1984). Few cases of true androdioecy have been convincingly demonstrated in the animal kingdom and include rhabditid nematodes (for review, see Weeks, 2012). Of androdioecious nematodes, the most intensively studied belong to the model genus Caenorhabditis, although androdioecious species have been confirmed or inferred for the genera Oscheius (Félix et al., 2001) and Panagrolaimus (Lewis et al., 2009). Perhaps most striking is the number of cases that have been documented in the family Diplogastridae Micoletzky, 1922, including Diplogasteroides magnus (Völk, 1950), Weingärtner, 1955 (Kiontke et al., 2001), Koerneria sudhausi Fürst von Lieven, 2008, and several species of Pristionchus Kreis, 1932 (Mayer et al., 2007).

Intensive sampling efforts have now revealed that androdioecy has arisen at least six times independently in Pristionchus (Mayer et al., 2007, 2009). Of the four previously described self-fertilizing species of Pristionchus, at least three are androdioecious: P. fissidentatus Kanzaki, Ragsdale, Herrmann, and Sommer, 2012; P. maupasi (Potts, 1910) Paramonov, 1952; and P. pacificus Sommer, Carta, Kim, and Sternberg, 1996. In the fourth species, P. entomophagus (Steiner, 1929) Sudhaus and Fürst von Lieven, 2003, males have been observed in only a few strains, although those males found can successfully outcross (D’Anna and Sommer, unpubl. data).

Dense taxon sampling, a sound phylogenetic framework, and the presence of multiple reproductive modes in a single nematode group are essential for gaining insight into the evolution of reproductive mode (Denver et al., 2011). Consequently, Pristionchus is particularly well suited for reconstructing the events leading to androdioecy. In addition, the laboratory tractability of Pristionchus nematodes offers the potential to uncover specific genetic mechanisms underlying evolution. As a satellite model to Caenorhabditis elegans, P. pacificus is supported by an analytical toolkit including extensive genetic and genomic resources (Sommer, 2009). For example, work in this system previously demonstrated the global sex-determination gene tra-1 to be functionally conserved in C. elegans and P. pacificus (Pires-da Silva and Sommer, 2004). Expanding the functional studies of derived reproductive modes will be made possible by the availability of closely related androdioecious species. Considerable advancements in understanding the evolution of sex determination in the androdioecious species C. elegans and C. briggsae (Haag, 2009; Thomas et al., 2012) demonstrate the power of such an approach. The establishment of a comparative context therefore awaits proper characterization of new potential models.

In the present study, we describe two new androdioecious species, P. boliviae n. sp. and P. mayeri n. sp., as well as a gonochoristic outgroup species, P. atlanticus n. sp. A molecular phylogenetic context, which had previously been inferred from several loci for the gonochoristic new species (Mayer et al., 2007), is extended to the other two new species and includes 26 ribosomal protein genes. Additionally, new comparative morphological data are presented for six species phylogenetically close to the newly described species. Besides providing reference points for studies of the evolution of sex, description of these species will expand the potential for more general comparative biology in the Pristionchus system.

Materials and Methods

Nematode isolation and cultivation: Pristionchus boliviae n. sp. was isolated from an adult Cyclocephala amazonica (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) collected near Buena Vista, Bolivia. Host beetles were dissected on a 2.0% agar plate, after which the plate was kept at room temperature for several weeks. Nematodes proliferated on bacteria associated with the host beetle cadavers. Individuals were thereafter transferred to nematode growth medium (NGM) agar plates seeded with Escherichia coli OP50, and have been since kept in laboratory culture on this medium. This medium was also used to maintain strains of P. mayeri n. sp. and P. atlanticus n. sp., which were isolated as described in Herrmann et al. (2010) and Mayer et al. (2007), respectively.

Molecular characterization and phylogenetic analysis:

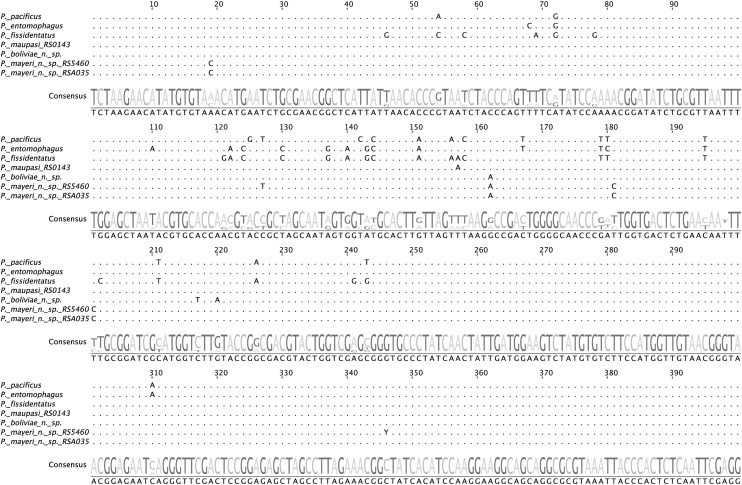

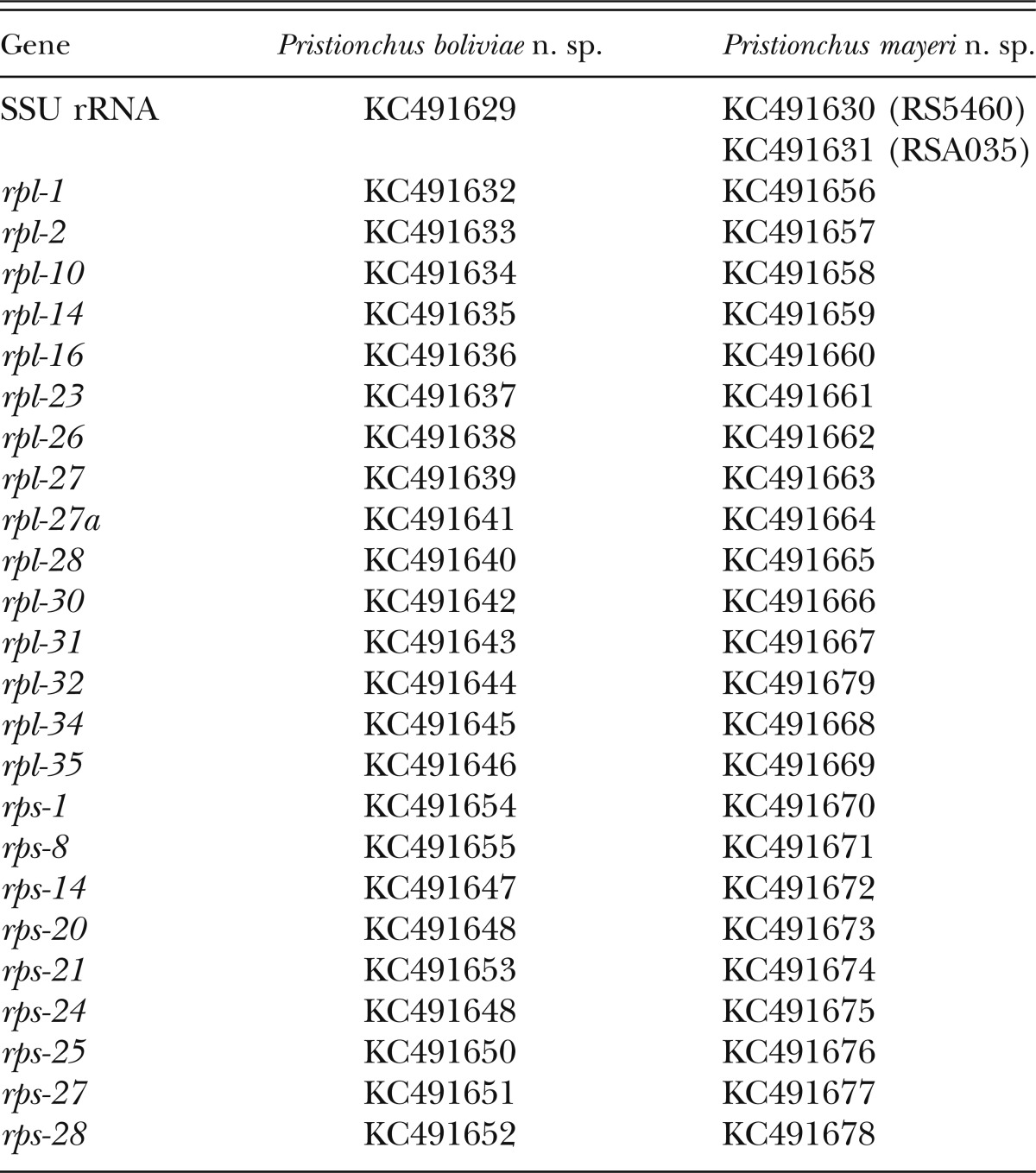

For species diagnosis and phylogenetic analysis, we amplified an approximately 1-kb fragment of the SSU rRNA gene using the primers SSU18A (5’-AAAGATTAAGCCATGCATG-3’) and SSU26R (5’-CATTCTTGGCAAATGCTTTCG-3’) (Floyd et al., 2002). The diagnostic fragment was approximately 500 bp of the 5’ terminal end and was sequenced using the primer SSU9R (5’-AGCTGGAATTACCGCGGCTG-3’). The partial SSU rRNA sequences of P. boliviae n. sp. and the type strain of P. mayeri n. sp. (RS5460) were original in this study and have been deposited in the GenBank database (Table 1). The diagnostic 472-bp fragment of the SSU rRNA gene was identical for all isolates of P. mayeri n. sp. except at one unambiguous nucleotide position (Fig. 1). This alternate sequence was found in several strains from La Réunion (RSA035), Mauritius, and Madagascar, and it has been deposited in GenBank (Table 1).

Table 1.

GenBank accession numbers for gene sequences obtained in this study.

Fig. 1.

Alignment of a 400-bp diagnostic fragment of the SSU rRNA gene for nominal hermaphroditic species of Pristionchus. Sequences were aligned manually. Points indicate nucleotides identical with consensus sequence. Numbering refers to base positions. Differences in sequences for newly described species are considered diagnostic of those species. Sequences for P. boliviae n. sp. and P. mayeri n. sp. are original in this study and have been deposited in GenBank as described in text. Other sequences were previously published and available in GenBank.

Phylogenetic analysis was performed on the partial SSU rRNA gene and 26 ribosomal protein genes. The aligned SSU rRNA fragment consisted of 851 positions. Ribosomal protein genes analyzed were those developed by Mayer et al. (2007) as marker loci based on their consistent presence in expressed sequence tag libraries of Pristionchus species. The dataset of ribosomal protein genes comprised a total of 10,758 aligned coding nucleotides. Genes included in the analysis were: rpl-1, rpl-2, rpl-10, rpl-14, rpl-16, rpl-23, rpl-26, rpl-27, rpl-27a, rpl-28, rpl-30, rpl-31, rpl-32, rpl-34, rpl-35, rpl-38, rpl-39, rps-1, rps-8, rps-14, rps-20, rps-21, rps-24, rps-25, rps-27, and rps-28. Ribosomal protein gene sequences for P. boliviae n. sp. and P. mayeri n. sp. are original in this study. All ribosomal protein gene sequences, except those for rpl-38 and rpl-39, which were less than 200 nucleotides in length, have been deposited in GenBank (Table 1). All information regarding genes, primers, and PCR conditions is given in Mayer et al. (2007).

The concatenated dataset of the partial SSU rRNA and ribosomal protein genes was aligned using MUSCLE (Edgar, 2004), followed by manual alignment in MEGA5.05 (Tamura et al., 2011) and by deletion of ambiguously aligned positions. The alignment was partitioned into four subsets: one for the partial SSU rRNA gene and three according to codon position for the concatenated set of ribosomal protein genes. The phylogeny was inferred under maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian optimality criteria, as implemented in RAxML v.7.2.8 (Stamatakis, 2006) and MrBayes 3.2 (Ronquist et al., 2012), respectively. The ML analysis invoked a general time reversible model with a gamma-shaped distribution of rates across sites. Bayesian analyses were initiated with random starting trees and were run with four chains for 2 × 106 generations. Markov chains were sampled at intervals of 100 generations. Two runs were performed for the analysis. After confirming convergence of runs and discarding the first 5 × 105 generations as burn-in, remaining topologies were used to generate a 50% majority-rule consensus tree with clade credibility values given as posterior probabilities (PP). Bayesian analysis allowed a mixed model of substitution with a gamma-shaped distribution and specified Koerneria sp. (RS1982) as outgroup. Model parameters were unlinked across character partitions in the analyses. Bootstrap support (BS) in the ML tree was evaluated by 1,000 pseudoreplicates.

Presence and reproductive function of males:

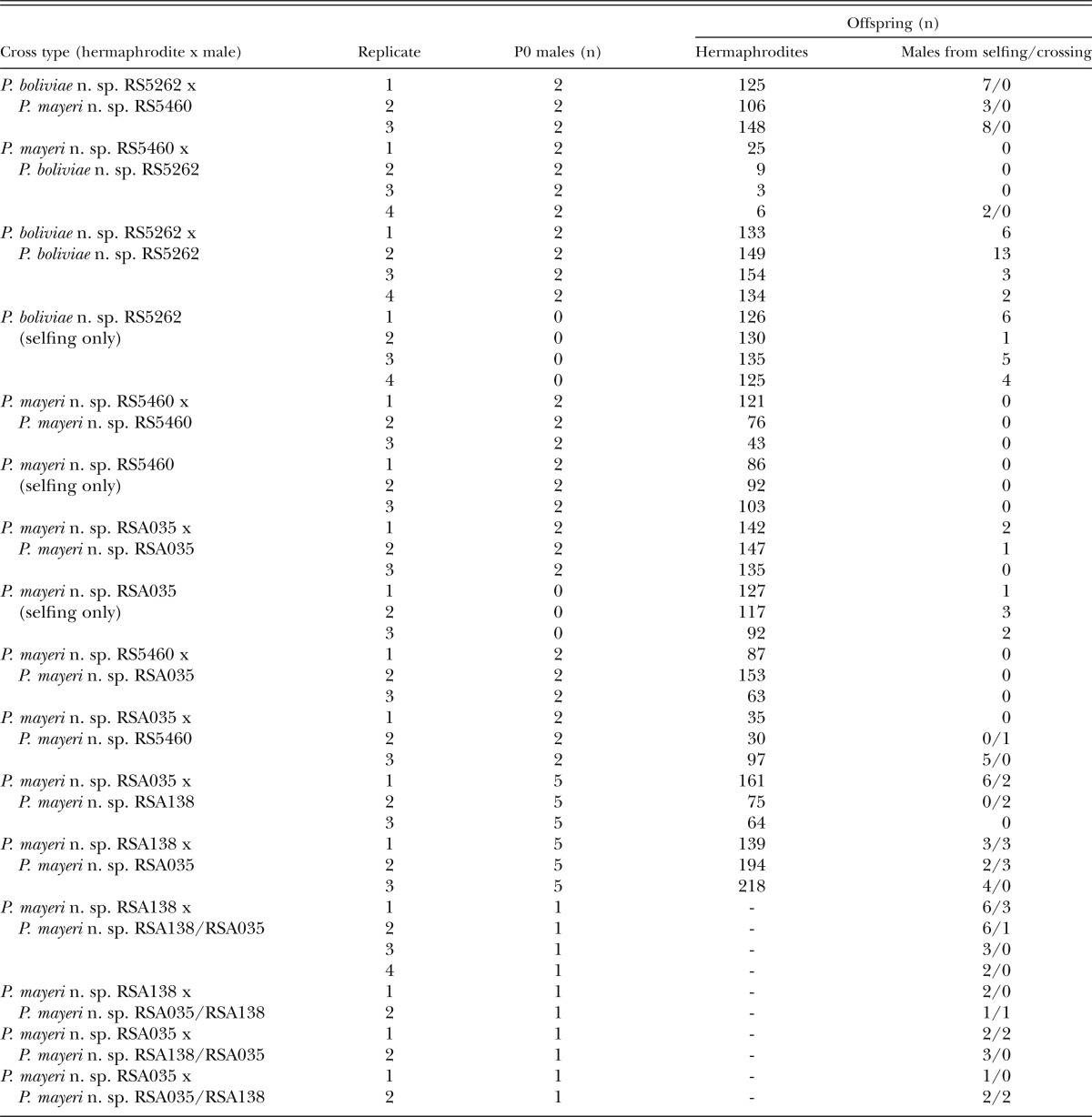

For P. boliviae n. sp. and P. mayeri n. sp., males were isolated from culture populations, after which crosses were set up between two males and one virgin (J4) hermaphrodite on plates seeded with a small bacterial lawn (25 μL E. coli OP50 in L-broth). Mating plates were maintained at 23°C. Because of the XX:X0 sex-determination system in Pristionchus, reproductive function of males was preliminarily considered successful if at least two males were present in the offspring of a single cross. For comparison, the frequency of meiotic X-chromosome nondisjunction was determined for nonmated hermaphrodites by allowing one J4 hermaphrodite per plate to produce progeny by selfing. Three replicates were performed per cross type. For P. boliviae n. sp., crosses were performed within the type strain (RS5262). For P. mayeri n. sp., crosses were performed within the type strain (RS5460), within the strain RSA035, which differed from the type strain by one nucleotide position in the diagnostic 472-bp SSU rRNA fragment described above, and between the type and RSA035 strains in both directions. In cases where crosses produced two or more F1 males, F1 males were sequenced to confirm their parentage, namely by detection of polymorphisms at known diagnostic sites in their SSU rRNA sequences. Crosses of all types were performed in triplicate.

Because of the limited success of crosses between strains of P. mayeri n. sp., especially in RSA035, additional crosses were performed between RSA035 and another isolate of P. mayeri n. sp., RSA138. Crosses each included five males and one J4 hermaphrodite placed on plates seeded with a bacterial lawn from 100 ml. In each of these crosses, the P0 strains differed at one nucleotide polymorphism in the SSU rRNA sequence (Fig. 1), such that parentage of offspring could be confirmed by sequencing. Additionally, F1 males resulting from these crosses were backcrossed to both P0 lines to test for reproductive isolation between P0 strains. Replicates were performed for each cross type as made possible by the availability of males.

Hybrid mating tests:

To test whether P. boliviae n. sp. and P. mayeri n. sp. are reproductively isolated from each other, hybrid crosses between these two putative species were performed. Each cross, set up on plates as described above, consisted of one J4 hermaphrodite from one species and two males of the opposite species. Crosses were performed reciprocally and in at least three replicates for each direction. All F1 males were sequenced to confirm their parentage.

Morphological observation and preparation of type material:

One- to two-week-old cultures of P. boliviae n. sp. (RS5262, RS5518), P. mayeri n. sp. (RS5460, RSA035), and P. atlanticus n. sp. (CZ3975) provided material for morphological observation. Observations by light microscopy (LM) and differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy were conducted using live nematodes, which were hand-picked from culture plates. For line drawings, specimens were mounted into water on slides and then relaxed by applying gentle heat. For morphometrics, specimens were mounted on slides with pads of 5% agar noble and 0.15% sodium azide and were additionally relaxed by heat when necessary. To prepare type material, nematodes were isolated from type strain cultures, rinsed in distilled water to remove bacteria, heat killed at 65°C, fixed in TAF to a final concentration of 5% formalin and 1.5% triethanolamine, and processed through a glycerol and ethanol series using Seinhorst’s method (see Hooper et al., 1986). Nomarski micrographs were taken using a Zeiss Axio Imager Z.1 microscope and a Spot RT-SE camera supported by the program MetaMorph v.7.1.3 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). For comparison with the newly described species, original LM observations were also made on live specimens of the following species: P. aerviorus (Cobb in Merrill and Ford, 1916) Chitwood, 1937; P. americanus Herrmann, Mayer, and Sommer, 2006; P. marianneae Herrmann, Mayer, and Sommer, 2006; P. maupasi (strain RS0143); P. pauli Herrmann, Mayer, and Sommer, 2006; and P. pseudaerivorus Herrmann, Mayer, and Sommer, 2006.

Ancestral state reconstruction of papillae characters:

To establish a set of diagnostic characters for a clade of Pristionchus including the three new species, male papillae arrangements were determined for species in the clade and reported in ventral view. These data were then used to map the evolution of male sexual characters in a clade including several self-fertilizing species. We reconstructed ancestral states of papilla characters by mapping them onto the phylogeny inferred from molecular sequences. Characters were mapped by simple parsimony, as implemented in Mesquite v.2.75 (Maddison and Maddison, 2011). The species P. japonicus Kanzaki, Ragsdale, Herrmann, Mayer, and Sommer, 2012 was selected as outgroup for character polarization. All other taxa were pruned from the tree prior to ancestral state reconstruction.

Results

Molecular characterization and phylogenetic analysis:

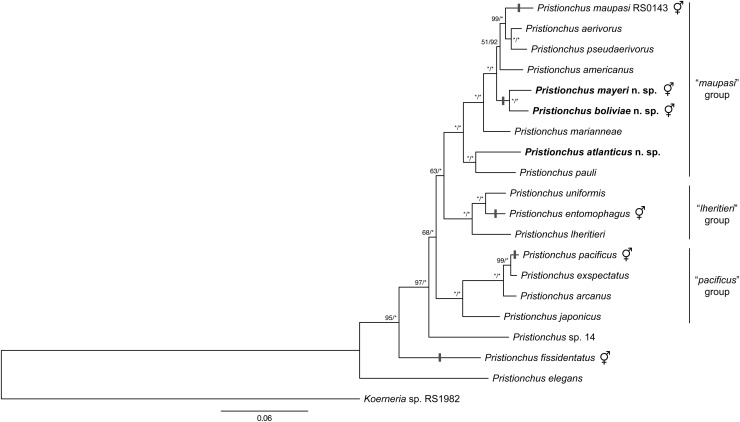

Sequences of a 472-bp fragment of the small subunit (SSU) rRNA gene were unique for each new species described herein (Fig. 1). Beyond diagnostics, a resolved phylogenetic infrastructure is essential to track character evolution, including the events leading to hermaphroditism. To accomplish this, we employed a dataset of 26 ribosomal protein genes and the partial SSU rRNA gene to infer relationships among Pristionchus species. The total concatenated alignment comprised 11,609 sites, 1881 of which were parsimony informative. This dataset provided high resolution for most relationships in the genus, including all nodes immediately preceding the mapped origins of hermaphroditism (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic relationships of Pristionchus species inferred by maximum likelihood (ML) from a partial SSU rRNA fragment and 26 ribosomal protein-coding genes. Independent evolutionary origins of hermaphroditism (steps indicated by gray bars) were mapped by simple parsimony. The ML tree with the highest log likelihood is shown. The proportion of trees in which the associated taxa clustered together in 1,000 bootstrap pseudoreplicates is shown next to the nodes (left value). Tree topology is identical with that from Bayesian inference, and posterior probabilities for corresponding nodes are also displayed (right value) on tree. Bootstrap support values above 50% are shown. Asterisks indicate 100% support. Tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site.

Tree topologies from ML and Bayesian analyses were identical. Only the ML tree is shown, along with support values from both analyses (Fig. 2). Results of the analysis show that P. boliviae n. sp. and P. mayeri n. sp. are sister taxa based on current taxon representation. Therefore, hermaphroditism in these two species is presently considered to have evolved once in their common ancestor. Consistent with previous phylogenetic analyses (Mayer et al., 2007, 2009; Kanzaki et al., 2012a, 2012b), three major clades of Pristionchus were strongly supported (100% BS and PP). One such clade included P. pauli, P. atlanticus n. sp., P. marianneae, P. americanus, P. boliviae n. sp., P. mayeri n. sp., P. aerivorus, P. pseudaerivorus, and P. maupasi and is designated herein as the “maupasi” group. Another strongly supported clade, including P. japonicus, P. arcanus Kanzaki, Ragsdale, Herrmann, Mayer, and Sommer, 2012; P. exspectatus Kanzaki, Ragsdale, Herrmann, Mayer, and Sommer, 2012; and P. pacificus, is designated as the “pacificus” group. The strongly supported clade referred to as the “lheritieri” group includes P. lheritieri (Maupas, 1919) Paramonov, 1952, P. entomophagus, and P. uniformis Fedorko and Stanuszek, 1971. Group designations indicate mutually exclusive clades and are unranked. Moreover, several species of Pristionchus, notably the putatively basal species P. elegans Kanzaki, Ragsdale, Herrmann, and Sommer, 2012 and P. fissidentatus, remain outside of this nomenclature.

Reproductive function of males:

To assess the reproductive function of males, we performed laboratory tests in the form of intraspecific and hybrid crosses (Table 2). All males obtained as a result of these crossing experiments had their SSU rRNA gene sequenced, where informative, to determine their genotype. Crosses of males to conspecific hermaphrodites resulted in multiple male progeny in P. boliviae n. sp., although virgin hermaphrodites also produced high numbers of males. Mating experiments could thus not definitively demonstrate the ability of P. boliviae n. sp. to outcross. Because hermaphrodites produce high numbers of males with or without outcrossing, we consider the species to be androdioecious, as defined in Weeks (2012). Crosses within P. mayeri n. sp. initially resulted in few or no F1 male progeny. Furthermore, crosses producing males in P. mayeri n. sp. always involved RSA035 mothers, and virgin RSA035 hermaphrodites also produced a strikingly high number of spontaneous males (Table 2). Therefore, to further test the ability of P. mayeri n. sp. to outcross, intraspecific crosses were performed using more (five) P0 males per cross and employed P0 strains that had distinct SSU rRNA sequences (Fig. 1), namely strains RSA035 and RSA138, allowing the genotyping of offspring to confirm paternity. Fathers sired males in at least one replicate in all attempted crosses of the latter strains (Table 2). Additionally, these F1 males could successfully cross to either P0 line, confirming that RSA035 and RSA138 belong to the same biological species (Table 2). Thus, P. mayeri n. sp. is functionally androdioecious.

Table 2.

Intraspecific and hybrid crosses of Pristionchus boliviae n. sp. and three strains of P. mayeri n. sp. Crosses within strains were performed to test the reproductive function of males. Crosses between strains were performed to test for reproductive isolation. To estimate the frequency of meiotic X-chromosome nondisjunction, all F1 hermaprodites and males were counted. All crosses were performed with a single virgin P0 hermaphrodite. Where parent strains had unique SSU rRNA sequences, including within P. mayeri n. sp., the parentage of male offspring was confirmed by sequencing and is indicated in the far-right column. Following crosses between RSA035 and RSA138, F1 males were backcrossed to both P0 lines to test for reproductive isolation between P0 strains. The genotypes of F1 males used in crosses are shown in the “cross type” column as maternal/paternal. Crosses between RSA035, RSA138, and their F1 offspring resulted in sired males, confirming that P. mayeri n. sp. is functionally androdioecious and that the parent strains, which differ in their SSU rRNA sequence, belong to the same biological species.

Hybrid mating tests:

Interspecific crosses between P. boliviae n. sp. hermaphrodites and P. mayeri n. sp. males were followed by multiple male progeny, although these males were confirmed by sequencing to be from selfing rather than crossing (Table 2). One replicate of the reciprocal cross resulted in two males, which were also confirmed to be spontaneous. Therefore, P. boliviae n. sp. and P. mayeri n. sp. showed prezygotic reproductive isolation and are considered to be unique biological species. Additionally, when compared with the reciprocal hybrid cross and intraspecific crosses, crosses between P. boliviae n. sp. males and P. mayeri n. sp. hermaphrodites showed a dramatic reduction in brood size, in one case consisting of as few as three hermaphrodite progeny (Table 2).

Morphology of the three new species:

Reflecting the close relationships among P. boliviae n. sp., P. mayeri n. sp., and P. atlanticus n. sp., as inferred from molecular phylogeny, is a general similarity in the morphology of these three species. To avoid redundancy, morphology common to all three new species is described first, followed by species-specific characters and diagnoses for each species.

Description of characters common to the three new species:

Adults.

Body cylindrical, stout. Cuticle thick, with fine annulation and clear longitudinal striations. Lateral field consisting of two lines, only weakly distinguishable from body striation. Head without apparent lips, and with six short and papilliform labial sensilla. Four small, papilliform cephalic papillae present in males, as typical for diplogastrid nematodes. Amphidial apertures located at level of posterior end of cheilostomatal plates. Stomatal dimorphism present, with stenostomatous (narrow mouthed) and eurystomatous (wide mouthed) forms occurring in both males and hermaphrodites/females. Dorsal pharyngeal gland clearly observed, penetrating dorsal tooth to gland opening. Anterior part of pharynx (= pro- and metacorpus) 1.5 times as long as posterior part (isthmus and basal bulb). Procorpus very muscular, stout, occupying one-half to two-thirds of corresponding body width. Metacorpus very muscular, forming well-developed median bulb. Isthmus narrow, not muscular. Basal bulb glandular. Pharyngo-intestinal junction clearly observed, well developed. Nerve ring usually surrounding middle or slightly more anterior part of isthmus. Excretory pore not conspicuous, ventrally located with variable position, between slightly anterior to basal bulb and pharyngo-intestinal junction or sometimes farther posterior, excretory duct extending anteriad and reflexed back to position of pore. Hemizonid not clearly observed. Deirid observed laterally, slightly posterior to pharyngo-intestinal junction. “Postdeirid” pores present and observed laterally, with positions inconsistent among individuals, five to eight for males and nine to 10 for females being confirmed by LM observation.

Stenostomatous form:

Cheilostom consisting of six per- and interradial plates. Incisions between plates not easily distinguished by LM observation. Anterior end of each plate rounded and elongated to stick out from stomatal opening and form a small flap. Gymnostom short, cuticular ring-like anterior end overlapping cheilostom internally. Dorsal gymnostomatal wall slightly thickened compared with ventral side.

Eurystomatous form:

Cheilostom divided into six distinct per- and interradial plates. Anterior end of each plate rounded and elongated to stick out from stomatal opening and form a small flap. Gymnostom with thick cuticle, forming a short, ring-like tube. Anterior end of gymnostom internally overlapping posterior end of cheilostomatal plates.

Male:

Ventrally arcuate, strongly ventrally curved at tail region when killed by heat. Testis single, along ventral side of body, anterior part reflexed to right side. Vas deferens not clearly separated from other parts of gonad. Three (two subventral and one dorsal) cloacal gland cells observed at distal end of testis and intestine. Spicules paired, separate. Thick cuticle around tail region, falsely appearing as a narrow leptoderan bursa in ventral view. Dorsal side of gubernaculum possessing a single, membranous, anteriorly directed process and a lateral pair of more sclerotized anteriorly and ventrally directed processes. Cloacal opening slit-like in ventral view. One small, ventral, single genital papilla (vs) on anterior cloacal lip. Papilla nomenclature follows Sudhaus and Fürst von Lieven (2003): all ventral papillae and the most anterior dorsal papilla are numbered by absolute position along the body axis, whereby the dorsal papilla is appended with a “d” (i.e., v2d or v3d); remaining dorsal papillae are designated as anterior (ad) or posterior (pd). Papillae v1-ad of almost equal size, rather large and conspicuous, v5 and v6 very small, sometimes difficult to observe by LM, v7, and pd small but larger than v5 and v6, i.e., intermediate between v1-ad and v5/v6 in size. Tip of v6 papillae split into two small papilla-like projections. v1-ad, v7, and pd papilliform and cone-shaped, borne directly from body, v5 and v6 each shrouded at base by a socket-like structure. Excluding terminal spike, tail about two cloacal body widths long. Bursa or bursal flap absent. Tail conical, with long spike, which has filiform distal end.

Hermaphrodite/female:

Relaxed or slightly ventrally arcuate when killed by heat. Gonad didelphic, amphidelphic. Each gonadal system arranged from vulva and vagina as uterus, oviduct, and ovotestis/ovary. Anterior gonad right of intestine, with uterus and oviduct extending ventrally and anteriorly on right of intestine and with a totally reflexed (= antidromous reflexion) ovotestis/ovary extending dorsally on left of intestine. Oocytes mostly arranged in multiple, sometimes more than five rows in distal two-thirds of ovotestis/ovary and in single row in remaining third of ovotestis/ovary, distal tips of each ovotestis/ovary reaching the oviduct of opposite gonad branch. Middle part of oviduct serving as spermatheca, sperm observed in distal part of oviduct, close to ovotestis/ovary. Eggs in single- to multiple-cell stage or even further developed at proximal part of oviduct (= uterus). Receptaculum seminis not observed. Dorsal wall of uterus at the level of vulva thickened and appears dark in LM observation. Four vaginal glands present but obscure. Vagina perpendicular to body surface, surrounded by sclerotized tissue. Vulva slightly protuberant in lateral view, pore-like in ventral view. Rectum about one anal body width long, intestinal-rectal junction surrounded by well-developed sphincter muscle. Three (two subventral and one dorsal) anal glands present at the intestinal/rectal junction, but not obvious. Anus in form of dome-shaped slit, posterior anal lip slightly protuberant. Phasmid about two anal body width posterior to anus. Tail long, distal end variable from filiform to long and conical.

Pristionchus boliviae n. sp.*

= Pristionchus sp. 16 apud Mayer et al. (2009)

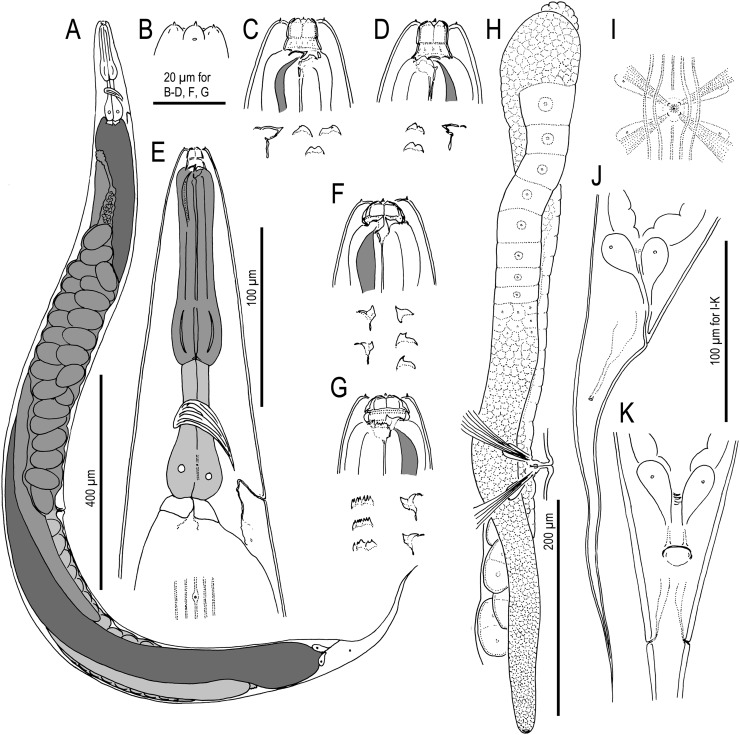

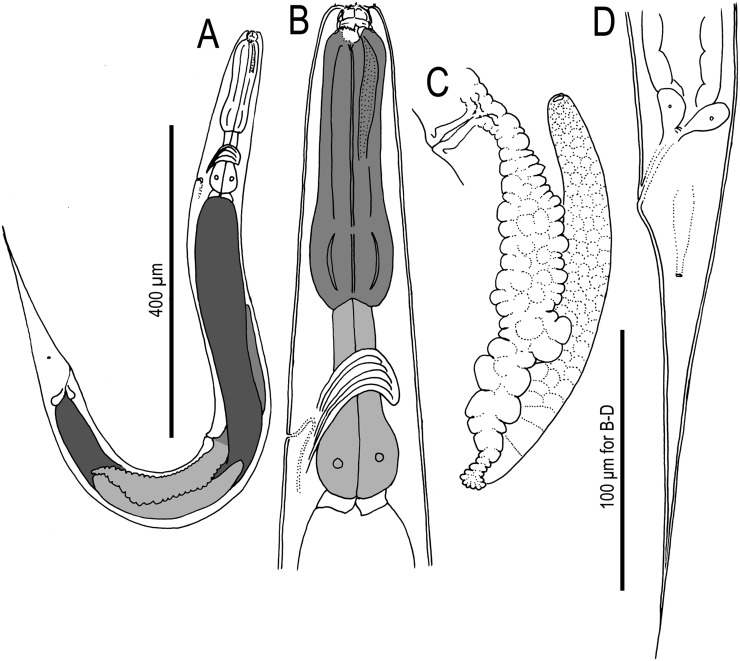

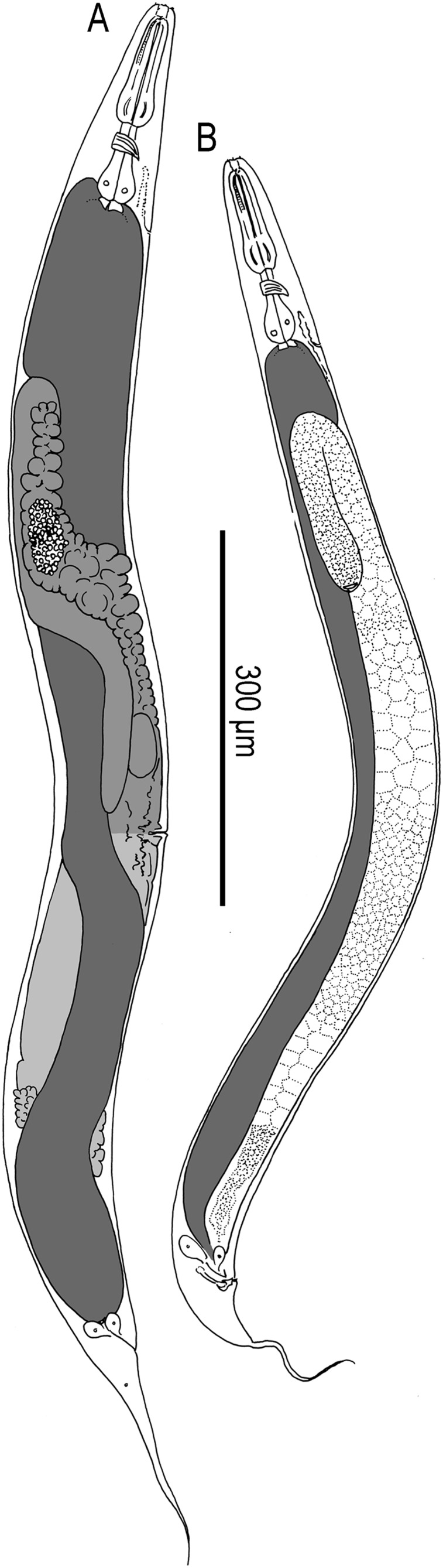

Fig. 3.

Adult hermaphrodite of Pristionchus boliviae n. sp.: A. Whole body of stenostomatous individual in right lateral view. B. Lip region in lateral view. C. Stenostomatous form in right lateral view, showing dorsal tooth (below, left) and three variants of right subventral ridge with two cusps (below, right). D. Stenostomatous form in left lateral view, showing two variants of left subventral ridge (below, left) and dorsal tooth (below, right). E. Neck region of stenostomatous form in right lateral view. F. Eurystomatous hermaphrodite in right lateral view, showing two variants of dorsal tooth (below, left) and three variants of right subventral tooth (below, right). G. Eurystomatous hermaphrodite in left lateral view, showing three variants of left subventral ridge (below, left) and two variants of dorsal tooth (below, right). H. Anterior gonadal branch in right lateral view. I. Vulva in ventral view. J. Tail in right lateral view. K. Anus in ventral view.

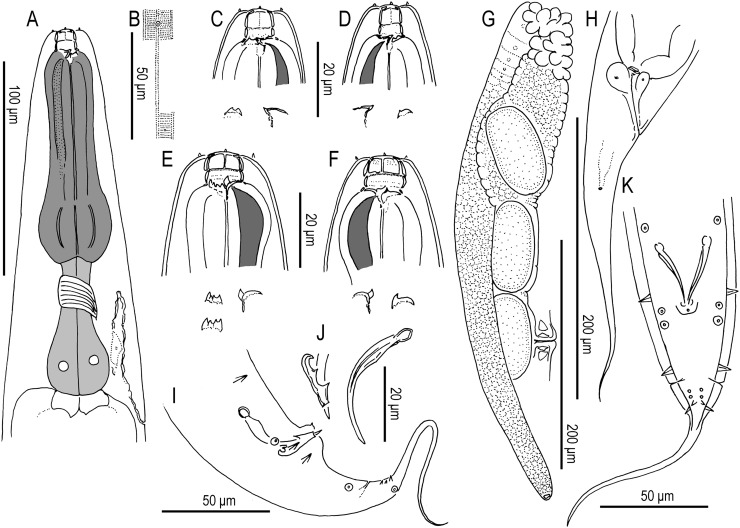

Fig. 4.

Adult male of Pristionchus boliviae n. sp.: A. Whole body in left lateral view, in addition to reflexed part of testis (right). B. Excretory pore in ventral view. C. Tail in right lateral view. D. Tail in ventral view. E,F. Two variants of gubernaculum in right lateral view. G. Spicule in right lateral view of spicule. H–J. Variation of male tail observed in strain RS5518. H. Arrowheads indicate asymmetry of v1 pair (right v1 is far anterior to left v1) and anterior position of v4. I. Arrowheads indicate malformed spicule and duplicated ad papilla. J. Arrowheads indicate extra anterior (“v0”) papilla and anterior positions of v2d and pd.

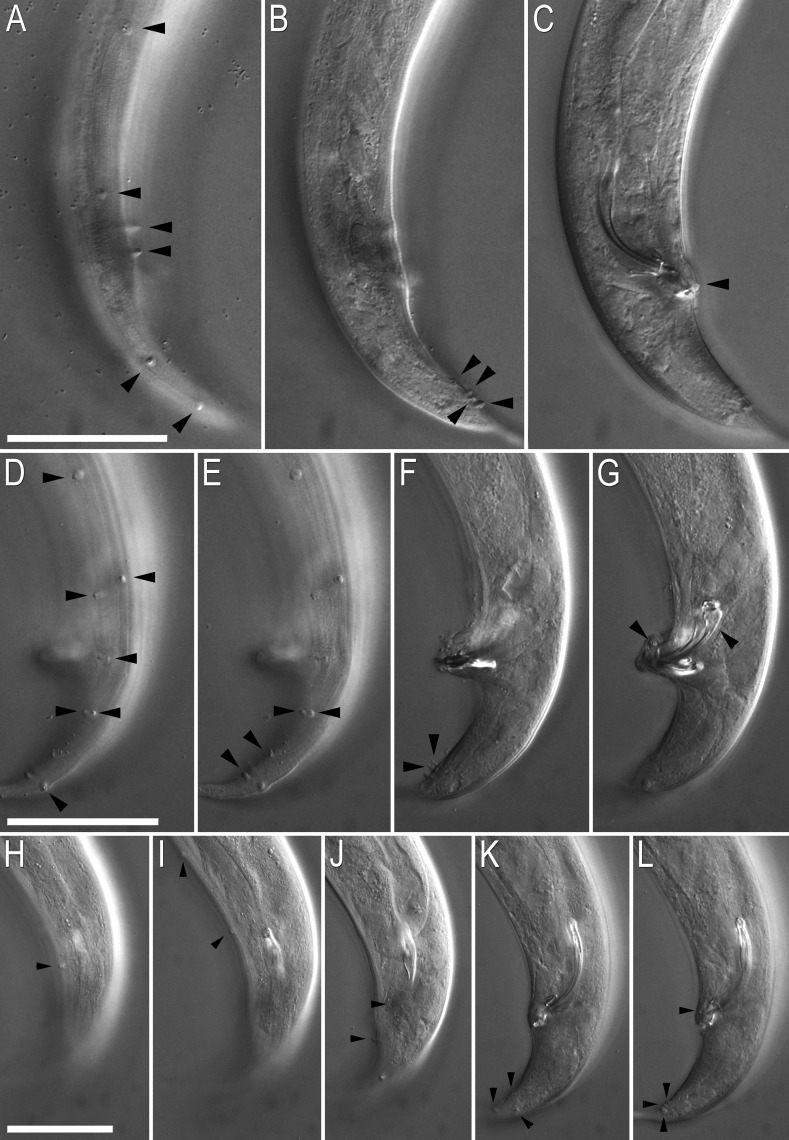

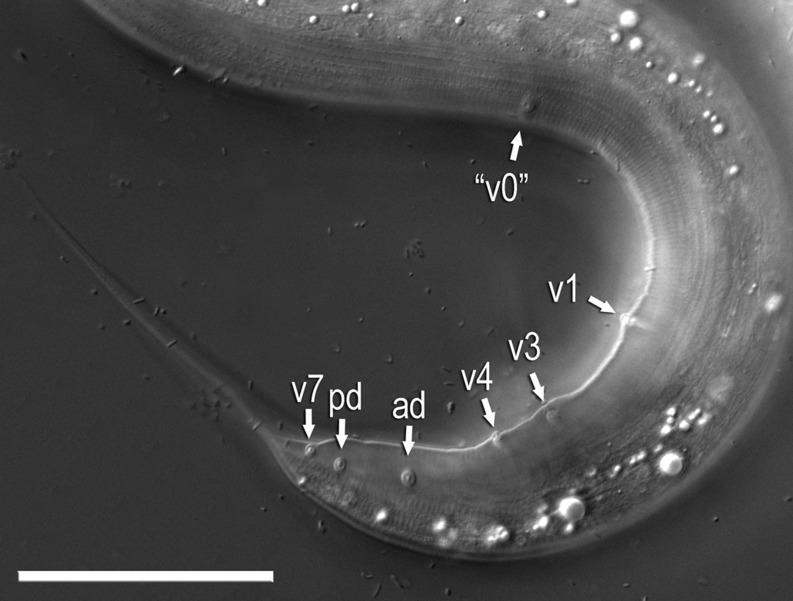

Fig. 5.

Variation in male sexual morphology in Pristionchus boliviae n. sp. (strain RS5518) (scale bars are 50 μm): A–C. DIC micrographs of a single individual, summarized in Fig. 4H, in different focal planes and at the same scale. Arrowheads from top to bottom indicate: v1, v2d, v3, v4, ad, and pd in (A); phasmid, v5, v6, and v7 in (B); unpaired ventral papilla (vs) in (C). D–G. A second individual, summarized in Fig. 4I. Arrowheads from top to bottom indicate: v1, v2d, v3, v4, ad (duplicated), and pd in (A); ad (duplicated), phasmid, and P8 in (B); v5 and v6 in (C); malformed spicule and vs in (D). H–L. A third individual, summarized in Fig. 4J. Arrowheads from top to bottom indicate: v2d in (A); “v0” (extra anterior papilla) and v1 in (B); v3, v4, and ad in (C); phasmid, v7, and pd in (D); and vs, v5, v6, and v7 in (E).

Fig. 6.

Young adult eurystomatous hermaphrodite of P. boliviae n. sp. (RS5262): A. Whole body in left lateral view. B. Neck region in left lateral view. C. Posterior gonadal branch in left lateral view. D. Tail in left lateral view.

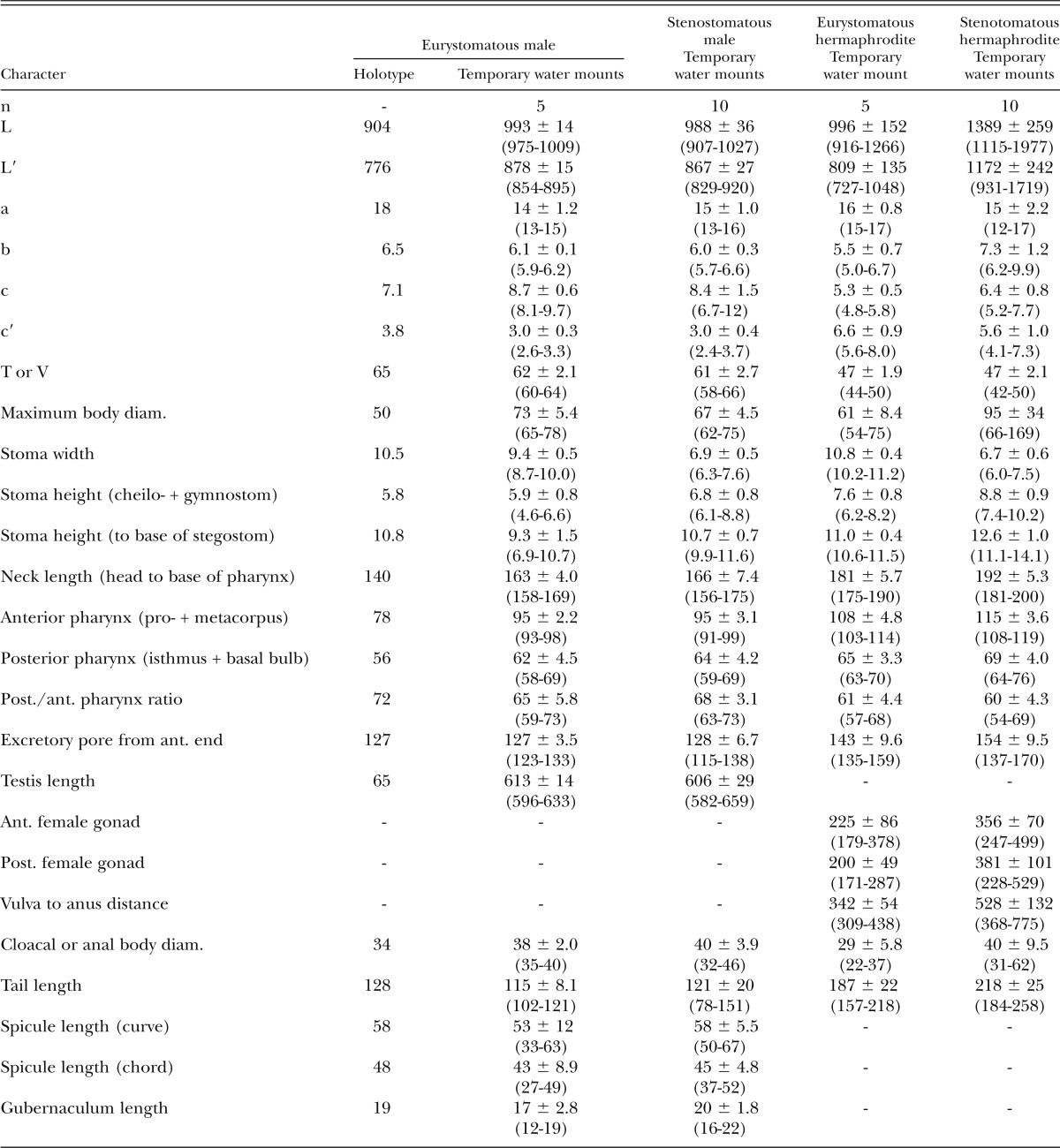

Measurements: See Table 3.

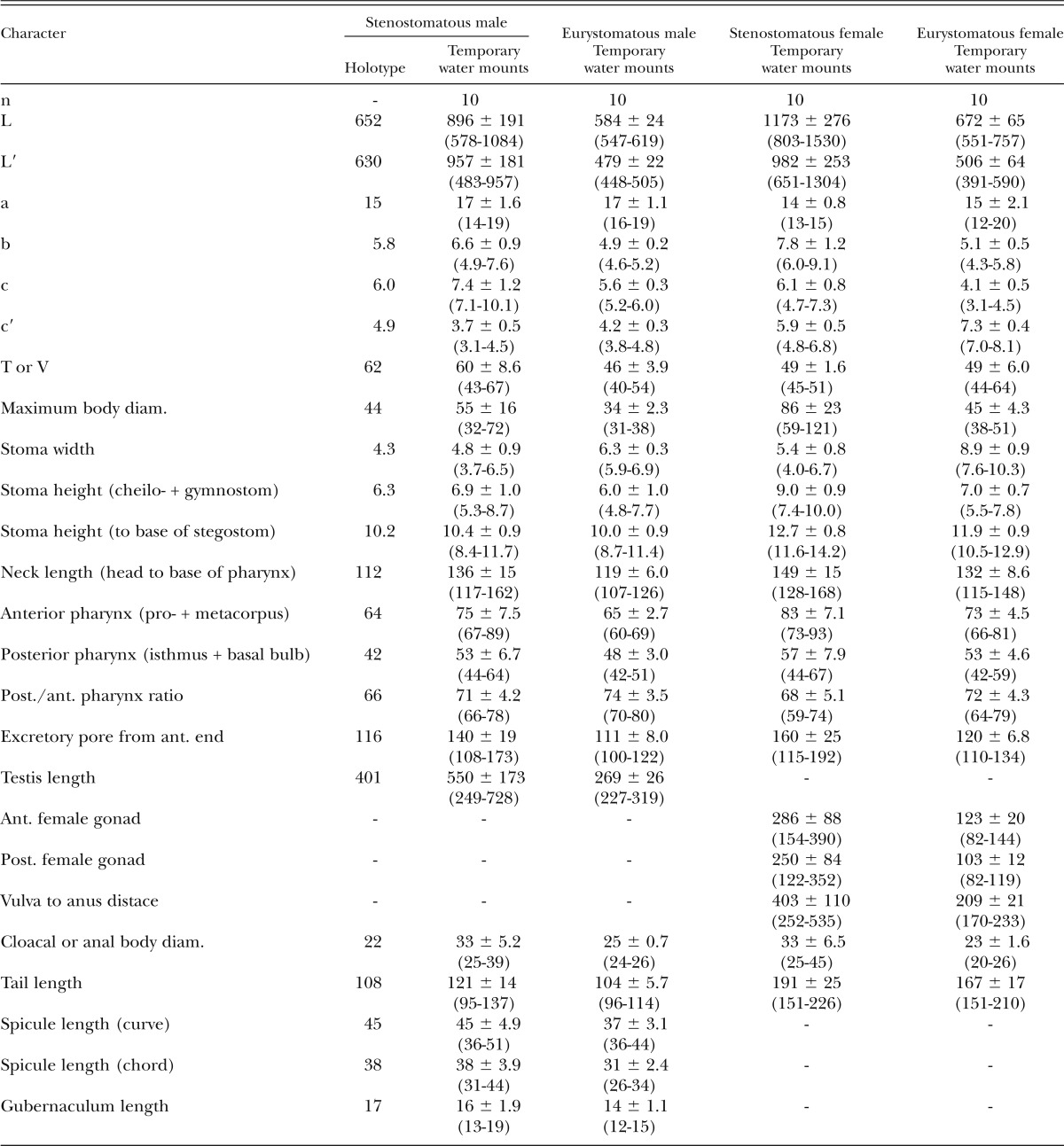

Table 3.

Morphometrics of eurystomatous male holotype (in glycerin) and male and hermaphrodite specimens of Pristionchus boliviae n. sp. (temporary water mounts). All measurements made in μm and given in the form: mean ± sd (range).

Description of species-specific characters:

Adults.

Species androdioecious, consisting of males and self-fertile hermaphrodites.

Stenostomatous form:

Stegostom bearing: a large, conspicuous, flint-shaped (or inverted “V”-shaped) dorsal tooth; in the right subventral sector, a crescent-shaped or half-circular ridge with one or two small cusps that vary in position from internally directed to apex of ridge; a crescent-shaped left subventral ridge with two to three small peaks, often with apparent cleavage between two main peaks. Dorsal tooth sclerotized at surface.

Eurystomatous form:

In type strain, typically smaller than stenostomatous form, possibly as a result of starvation. Stegostom bearing: a large claw-like dorsal tooth, with large base of varying size; a large claw-like right subventral tooth, occasionally with a split cusp; in the left subventral sector, a row of four to eight small- to medium-sized triangular subventral peaks projecting from a common cuticular plate that appears split midway along its length. Dorsal and right subventral teeth movable. Left subventral denticles immovable.

Male:

Spontaneous males relatively common, often more than 5% of brood (strain RS5262). Spermatogonia arranged in about 10 rows in reflexed part, then well-developed spermatocytes arranged as eight to 10 rows in anterior two-thirds of main branch, then mature amoeboid spermatids arranged in multiple rows in remaining, proximal part of gonad. Spicules slender, smoothly curved in ventral view, adjacent to each other for distal third of their length, each smoothly tapering to pointed distal end. Spicule in lateral view smoothly ventrally arcuate, giving spicule about 100° curvature, slender oval manubrium, sometimes three times longer than wide, present at anterior end; lamina-calomus complex not ventrally expanded, such that anterior end of calomus is not offset from lamina, lamina smoothly tapering to pointed distal end. In one individual, spicules were grossly protracted with flattened manubria. Gubernaculum conspicuous, stout, less than one-third of spicule in length, broad anteriorly such that dorsal wall is recurved and dorsal and ventral walls separate at a 45° angle at posterior end. In lateral view, anterior part of gubernaculum with two serial curves separated by an acute, anteriorly directed process, with open anterior curvature and a deep terminal curvature about a third of gubernaculum length; posterior part forming a short tube, about one-third of gubernaculum length, enveloping spicules. Nine pairs of genital papillae and a pair of phasmids present and arranged as <v1, (v2d, v3), C, v4, ad, Ph, (v5, v6, v7, pd)> (= <P1, (P2d, P3), C, P4, P5d, Ph, (P6, P7, P8, P9d)> in nomenclature of Kanzaki et al., 2012a, 2012b). Absolute positions of papillae, particularly v1–v4, highly variable (Figs. 4H–4J,5). Position of v1 papillae variable and asymmetrical, being from level of manubrium to much farther anterior, v2d slightly anterior to more than one cloacal body width anterior to C, v3 more consistent, usually within one-half cloacal body width anterior to v4, C and v4 clustered within two-thirds cloacal body width, ad closer to v4 than to v5 or a half cloacal width posterior to v4, Ph at about same level of or just anterior to v5, v7 lateral to v5 and v6, such that v5–v7 form a triangle, and pd anterior, from level of v5/v6 to just posterior to phasmid. Additional papillae sometimes observed: one individual had a single papilla (“v0”) far anterior to v1, and another individual had a duplicated ad (P5d) papilla on one side.

Diagnosis and relationships:

Besides its generic characters, P. boliviae n. sp. is diagnosed by male genital papillae arranged as <v1, (v2d, v3), C, v4, ad, Ph, (v5, v6, v7, pd)>, whereby v1–v4 are highly variable in absolute position, particularly v1, positions of which are also often asymmetrical, v7 is lateral to v5/v6, v9 is at level of v5/v6 to just posterior of phasmid, and with occasional additional papillae, including “v0” and duplicated papillae (e.g., ad). Pristionchus boliviae n. sp. is distinguished from the closest known hermaphroditic species, P. mayeri n. sp., by a slender (up to three times longer than wide) vs. rounded (up to twice as long as wide) manubrium, although character states overlap in these two species; the posterior tube of gubernaculum being short (one-third gubernaculum length) vs. long (one-half length), and with the anterior opening of the tube being open, i.e., ventral and dorsal walls separating at 45° angle vs. narrow, i.e., walls separating at 30°; lamina-calomus complex not vs. distinctly ventrally expanded; papilla v7 consistently lateral to vs. in line with v5/v6; its unique SSU rRNA sequence, which differs from that of P. mayeri n. sp. in five to six nucleotide positions in a diagnostic 472-bp fragment of the gene. It is further distinguished from P. mayeri n. sp. by prezygotic reproductive isolation, namely the inability to form F1 hybrids. The species is distinguished from the following species by a hermaphroditic vs. gonochoristic mode of reproduction: the morphologically and molecularly circumscribed species P. aerivorus, P. elegans, P. lheritieri, and P. uniformis; the molecularly and biologically circumscribed species P. americanus, P. marianneae, P. pauli, and P. pseudaerivorus; the morphologically, molecularly, and biologically circumscribed species P. arcanus, P. exspectatus, and P. japonicus.

Type host (carrier) and locality:

The culture from which the type specimens were obtained was originally isolated by M. Herrmann from an adult Cyclocephala amazonica (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) collected 4 km south of Buena Vista, Bolivia (17°29.074’ S, 63°38.775’ W) in November 2006.

Distribution:

Besides its collection from the type locality and type host, the species was isolated as strain RS5518 from an unidentified scarab beetle in Colombia.

Type material, type strain, and nomenclatural registration:

Holotype eurystomatous male, two paratype stenostomatous males, one paratype eurystomatous hermaphrodite, and three paratype stenostomatous hermaphrodites deposited in the University of California Riverside Nematode Collection (UCRNC), CA. Four paratype stenostomatous hermaphrodites (SMNH Type-8421) deposited in the Swedish Natural History Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. Four paratype stenostomatous hermaphrodites deposited in the Natural History Museum Karlsruhe, Germany. The type strain is available in living culture and as frozen stocks under culture code RS5262 in the Department of Evolutionary Biology, Max Planck Institute (MPI) for Developmental Biology, Tübingen, Germany, and can be provided to other researchers upon request. The new species binomial has been registered in the ZooBank database (zoobank.org) under the identifier [94C3F8D7-AF07-4BB7-B377-881E112A6F04].

Pristionchus mayeri n. sp.*

= Pristionchus sp. 25 apud Herrmann et al. (2010)

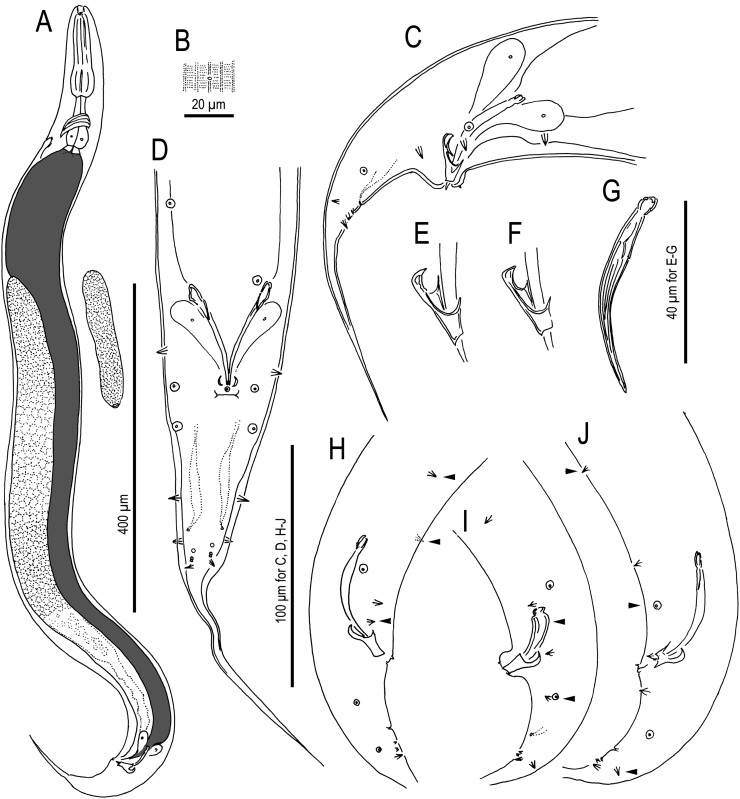

Fig. 7.

Adult hermaphrodite of Pristionchus mayeri n. sp.: A. Whole body of stenostomatous individual in left lateral view. B. Neck region of stenostomatous individual in right lateral view. C. Stenostomatous form in left lateral view, showing two variants of left subventral ridge (below, left) and dorsal tooth (below, right). D. Stenostomatous form in right lateral view, showing dorsal tooth and two variants of left subventral ridge. E. Eurystomatous form in left lateral view, showing three variants of left subventral ridge (below, left) and dorsal tooth (below, right). F. Eurystomatous form in right lateral view, showing dorsal tooth (below, left) and right subventral tooth (below, right). G. Deirid. H. Anterior gonadal branch in right lateral view. I. Tail in left lateral view.

Fig. 8.

Adult male of Pristionchus mayeri n. sp.: A. Whole body of stenostomatous individual in right lateral view. B. Gubernaculum and spicule in right lateral view. C. Tail in ventral view. D. Tail in right lateral view.

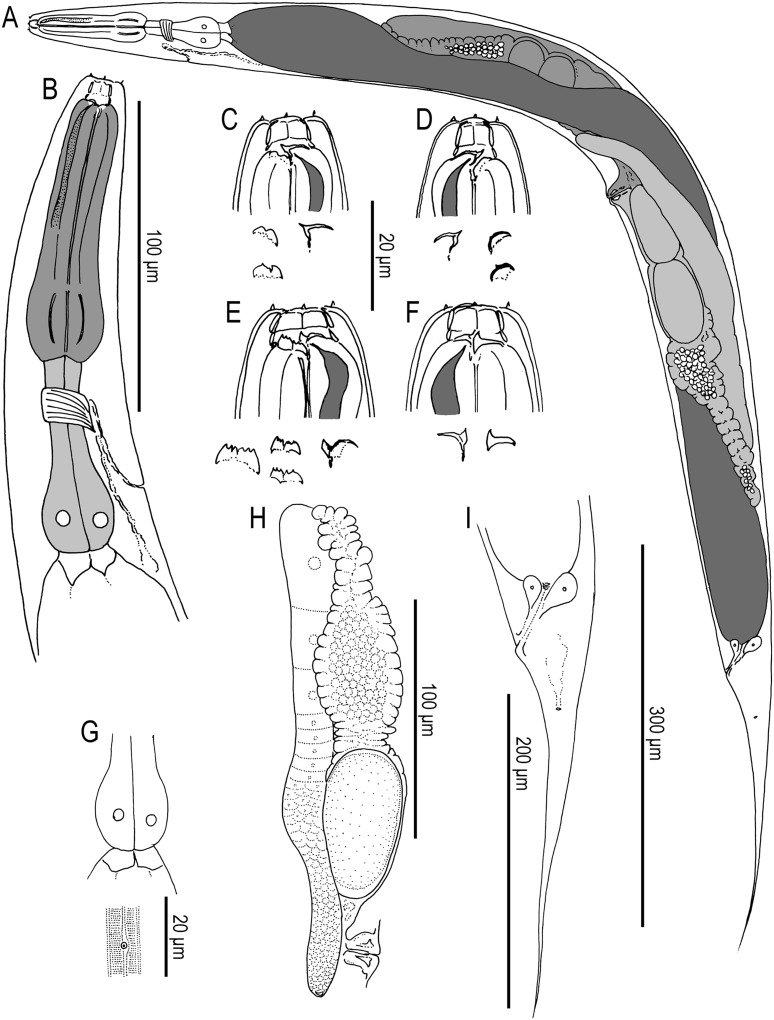

Fig. 9.

Male genital papillae of Pristionchus mayeri n. sp.: View is left lateral. Scale bar is 20 μm. Characteristic of this species is closeness (less than one-half cloacal body width) of papilla v3 to v4 and a position of pd overlapping or anterior to v5–v7. Papilla arrangement is unusually variable in this species, as sometimes shown by the presence of an extra anterior papilla “v0.”

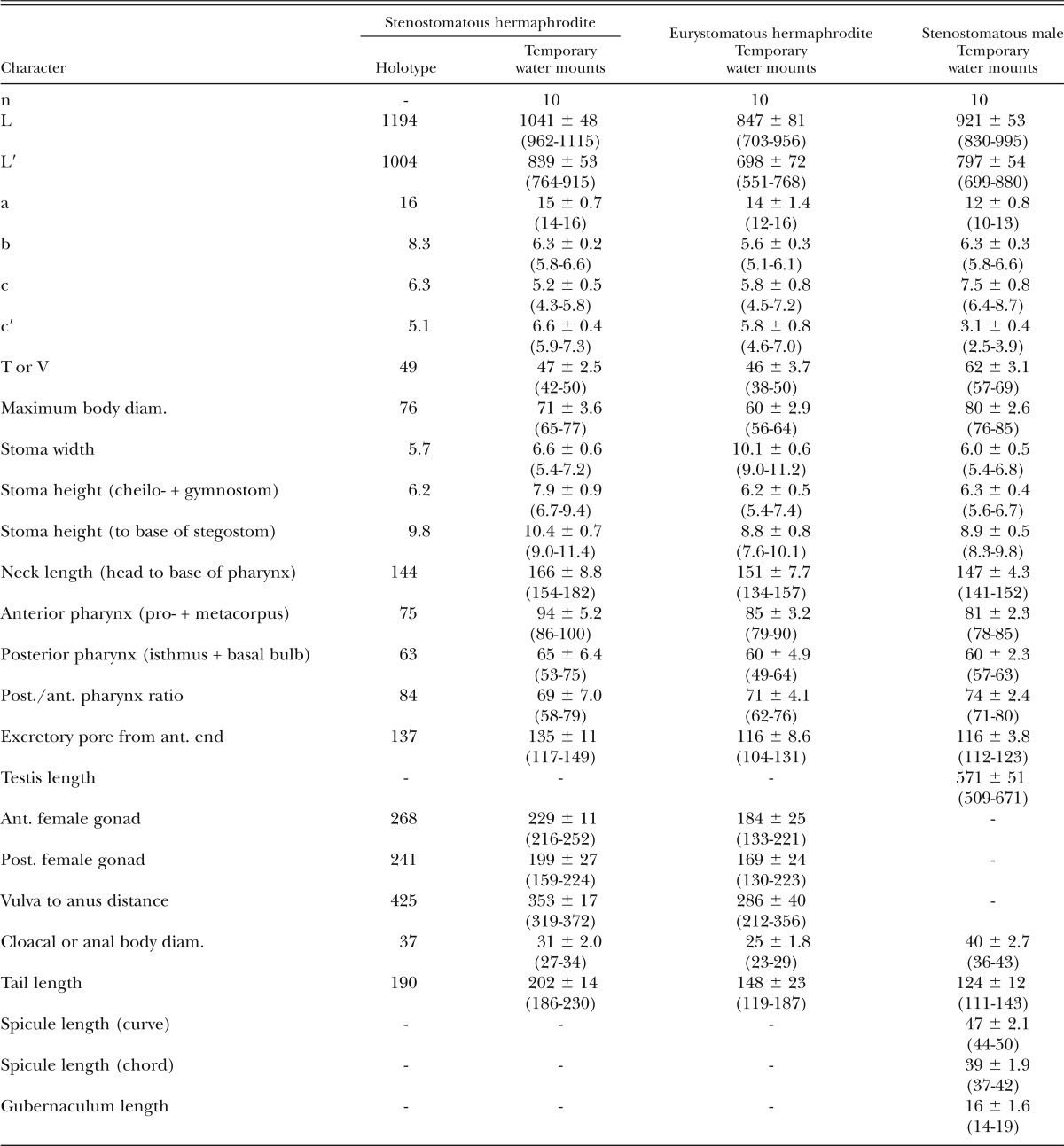

Measurements: See Table 4.

Table 4.

Morphometrics of stenostomatous hermaphrodite holotype (in glycerin) and hermaphrodite and male specimens of Pristionchus mayeri n. sp. (temporary water mounts). All measurements made in μm and given in the form: mean ± sd (range).

Description of species-specific characters:

Adults:

Species androdioecious, consisting of males and self-fertile hermaphrodites.

Stenostomatous form:

Stegostom bearing: a large, conspicuous, flint-shaped (or inverted “V”-shaped) dorsal tooth; in the right subventral sector, a crescent-shaped or half-circular ridge with a small, short, and pointed subventral denticle; in the left subventral sector, a crescent-shaped ridge with two small peaks, often with apparent cleavage between two main peaks. Dorsal tooth sclerotized at surface.

Eurystomatous form:

Stegostom bearing: a large claw-like dorsal tooth; a large claw-like right subventral tooth; in the left subventral sector, a row of left subventral denticles of varying numbers and size, i.e., six to eight medium-sized and small cusps, sometimes with irregular shape, all projecting from a common cuticular plate that appears split midway along its length. Dorsal and right subventral teeth movable. Left subventral denticles immovable.

Male:

Spontaneous males rare (< 1%, strain RS5460) to relatively common (up to 5%, RSA035) in culture. Spermatogonia arranged in four to 10 rows in reflexed part, then well-developed spermatocytes arranged as three to eight rows in anterior two-thirds of main branch, then mature amoeboid spermatids arranged in multiple rows in remaining, proximal part of gonad. Spicules smoothly curved in ventral view, adjacent to each other for distal third of their length, each smoothly tapering to pointed distal end. Spicule in lateral view smoothly ventrally arcuate, giving spicule about 100° curvature, with wide, rounded manubrium present at anterior end; lamina-calomus complex expanded just posterior to manubrium, then smoothly tapering to pointed distal end. Gubernaculum conspicuous, about one-third of spicule in length, slightly broader anteriorly such that dorsal and ventral walls separate at a 30° angle at posterior end. In lateral view, anterior part of gubernaculum with two serial curves separated by a ventrolaterally directed cusp and with deep, convex, terminal curvature two-fifths to half of gubernaculum length; posterior part forming a tube, about half of gubernaculum length, enveloping spicules. With usually nine pairs of genital papillae and a pair of phasmids present and arranged as <v1, (C, v2, v3d), v4, ad, Ph, (v5, v6, v7, pd)> (= <P1, (C, P2, P3d), P4, P5d, Ph, (P6, P7, P8, P9d)> in nomenclature of Kanzaki et al., 2012a, 2012b). Some individuals with extra papilla or pair of papillae (“v0”) about two cloacal body widths anterior of v1. Single or pair of v1 sometimes missing. Positions of v1 papillae asymmetrical and located about one cloacal body width posterior to cloacal slit, v2 twice as far from v1 than from v4, v3d slightly or conspicuously anterior to v2, C and v3 close to (within one-half cloacal body width) of v4, ad located middle of v4 and v6, Ph around middle between ad and v5 or close to ad, v5–v7 linearly arranged, and pd variable, from same level as v7 to slightly anterior of v5.

Diagnosis and relationships:

Besides its generic characters, P. mayeri n. sp. is diagnosed by male genital papillae arranged as <v1, (C, v2, v3d), v4, ad, Ph, (v5, v6, v7, pd)>, whereby v3 is within one-half cloacal body width of v4 and pd is at same level as or anterior to v7, and by the presence in some individuals of an additional, anterior “v0” papilla, either single or as a pair. Pristionchus mayeri n. sp. is distinguished from the closest known hermaphroditic species, P. mayeri n. sp., by a rounded (up to twice as long as wide) vs. slender (up to three times longer than wide) manubrium, although character states overlap in these two species; the posterior tube of gubernaculum being long (one-half gubernaculum length) vs. short (one-third length), and with the anterior opening of the tube being narrow, i.e., ventral and dorsal walls separating at 30° angle vs. open, i.e., walls separating at 45°; lamina-calomus complex distinctly vs. not ventrally expanded; v7 papilla in line with vs. consistently lateral to v5/v6; its unique SSU rRNA sequence, which differs from that of P. boliviae n. sp. in five to six nucleotide positions in a diagnostic 472-bp fragment of the gene. It is further distinguished from P. boliviae n. sp. by prezygotic reproductive isolation, namely the inability to form F1 hybrids. The species is distinguished from the following species by a hermaphroditic vs. gonochoristic mode of reproduction: the morphologically and molecularly circumscribed species P. aerivorus, P. elegans, P. lheritieri, and P. uniformis; the molecularly and biologically circumscribed species P. americanus, P. marianneae, P. pauli, and P. pseudaerivorus; the morphologically, molecularly, and biologically circumscribed species P. arcanus, P. exspectatus, and P. japonicus.

Type host (carrier) and locality:

The culture from which the type specimens were obtained was originally isolated from an adult Hoplochelus marginalis (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) collected by M. Herrmann from Trois Bassins on La Réunion Island in January 2009 (Herrmann et al., 2010).

Distribution:

Besides its collection from the type locality and type host, it was isolated from Adoretus sp. (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) at Grand Étang and Colorado during subsequent trips to La Réunion. The species was also isolated from soil in Madagascar and from Adoretus sp., Heteronychus licas, Hyposerica tibialis, Hy. vinsoni, and Phyllophaga smithi (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) in Lakaz Chamarel and Black River Gorges National Park in Mauritius.

Type material, type strain, and nomenclatural registration:

Holotype stenostomatous hermaphrodite, three paratype stenostomatous hermaphrodites, one paratype eurystomatous hermaphrodite, and two paratype stenostomatous males deposited in the UCRNC, CA. Four paratype stenostomatous hermaphrodites (SMNH Type-8422) deposited in the Swedish Natural History Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. Four paratype stenostomatous hermaphrodites deposited in the Natural History Museum Karlsruhe, Germany. The type strain is available in living culture and as frozen stocks under culture code RS5460 in the Department of Evolutionary Biology, MPI for Developmental Biology, Tübingen, Germany, and can be provided to other researchers upon request. The new species binomial has been registered in the ZooBank database (zoobank.org) under the identifier [B15074FC-0903-4E7E-81A8-EC2040F229D2].

Pristionchus atlanticus n. sp.*

= Pristionchus sp. 3 apud Mayer et al. (2007, 2009)

Fig. 10.

Adults of Pristionchus atlanticus n. sp.: View is right lateral. A. Whole body of adult stenostomatous female. B. Whole body of adult stenostomatous male.

Fig. 11.

Pristionchus atlanticus n. sp.: A–H. Adult female. I–K. Adult male. A. Neck region of stenostomatous individual in right lateral view. B. Deirid (above) and “postdeirid” (below). C. Stenostomatous form in left lateral view, showing left subventral ridge (below, left) and dorsal tooth (below, right). D. Stenostomatous form in right lateral view, showing dorsal tooth (below, left) and right subventral ridge (below, right). E. Eurystomatous form in left lateral view, showing two variants of the left subventral ridge, which is host to four pointed cusps (below, left), and dorsal tooth (below, right). F. Eurystomatous form in right lateral view, showing dorsal tooth (below, left) and right subventral tooth (below, right). G. Anterior gonadal branch in right lateral view. H. Tail in right lateral view. I. Tail in right lateral view. J. Gubernaculum and spicule in right lateral view. K. Tail in ventral view.

Measurements: See Table 5.

Table 5.

Morphometrics of stenomatous male holotype (in glycerin) and male and female specimens of Pristionchus atlanticus n. sp. (temporary water mounts). All measurements made in μm and given in the form: mean ± sd (range).

Description of species-specific characters:

Adults:

Species gonochoristic (i.e., dioecious), with males and females.

Stenostomatous form:

Stegostom bearing: a large, conspicuous, flint-shaped (or inverted “V”-shaped) dorsal tooth; a crescent-shaped right subventral ridge with minute denticle on medial (inner) side; two bump-like (blunt) left subventral denticles projecting from a common cuticular plate, often with apparent cleavage between two main peaks. Dorsal tooth sclerotized at surface.

Eurystomatous form:

In type strain, typically smaller than stenostomatous form, possibly as a result of starvation. Stegostom bearing: a large claw-like dorsal tooth; a large claw-like right subventral tooth; in the left subventral sector, a row of usually four medium-sized to large pointed subventral cusps projecting from a common cuticular plate that appears split midway along its length. Dorsal and right subventral teeth movable. Left subventral denticles immovable.

Male:

Spicules smoothly curved in ventral view, adjacent to each other for distal third of their length, each smoothly tapering to pointed distal end. Spicule in lateral view smoothly ventrally arcuate, giving spicule about 100° curvature, oval manubrium present at anterior end; lamina-calomus complex expanded just posterior to manubrium, then smoothly tapering to pointed distal end. Gubernaculum conspicuous, about one-third of spicule in length, relatively narrow anteriorly such that dorsal and ventral walls separate at a 15° angle at posterior end. In lateral view, anterior part of gubernaculum with two serial curves separated by anteriorly and ventrally directed process with shallow but distinctly concave terminal curvature; posterior part forming a tube enveloping spicules. Nine pairs of genital papillae and a pair of phasmids present and arranged as <v1, v3d, (C, v2), v4, ad, Ph, (v5, v6, v7), pd> (= <P1, P2d, (C, P3), P4, P5d, Ph, (P6, P7, P8), P9d> in nomenclature of Kanzaki et al., 2012a, 2012b). Positions of v1 papillae about one cloacal body width posterior to cloacal slit, C/v3 and v4 very close to each other (clustered within less than one-quarter cloacal body width), ad twice as far from v4 than from v5, Ph midway between ad and v5, v5 located less than ½ cloacal body width posterior to ad, v5–v7 linearly arranged. Tail spike about two cloacal body widths long.

Diagnosis and relationships:

Besides its generic characters, P. atlanticus n. sp. is diagnosed by male genital papillae arranged as <v1, v3d, (C, v2), v4, ad, Ph, (v5, v6, v7), pd>, whereby v2d and v4 are very close to each other (within one-quarter cloacal body width) and also far from both v1 and ad, and whereby pd is clearly posterior to v7. Pristionchus atlanticus is separated from all other gonochoristic species in the maupasi group by reproductive isolation (Herrmann et al., 2006). The species is distinguished from the closest known gonochoristic species, P. pauli, by v3 and v4 being separated by less than one-quarter vs. about one-half cloacal body width. It is further distinguished from all other gonochoristic species by its unique SSU rRNA sequence, and it differs from P. pauli in at least two nucleotide positions in a diagnostic 472-bp fragment of the gene (Herrmann et al., 2006).

Type host (carrier) and locality:

The culture from which the type specimens were obtained was originally isolated by Andrew Chisholm and Marie-Anne Félix from soil in a flowerbed at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, NY.

Type material, type strain, and nomenclatural registration:

Holotype stenostomatous male, four paratype stenostomatous females, and three paratype eurystomatous females deposited in the UCRNC, CA. Two paratype stenostomatous males, two paratype stenostomatous females, and one paratype eurystomatous hermaphrodite (SMNH Type-8418–SMNH Type-8420) deposited in the Swedish Natural History Museum, Stockholm, Sweden. Three paratype stenostomatous males, two paratype stenostomatous females, and one paratype eurystomatous female deposited in the Natural History Museum Karlsruhe, Germany. The type strain is available in living culture and as frozen stocks under culture code CZ3975 in the Department of Evolutionary Biology, MPI for Developmental Biology, Tübingen, Germany and can be provided to other researchers upon request. The new species binomial has been registered in the ZooBank database (zoobank.org) under the identifier [8F62BBFE-35DC-45E2-BAB4-E5F3307E8A12].

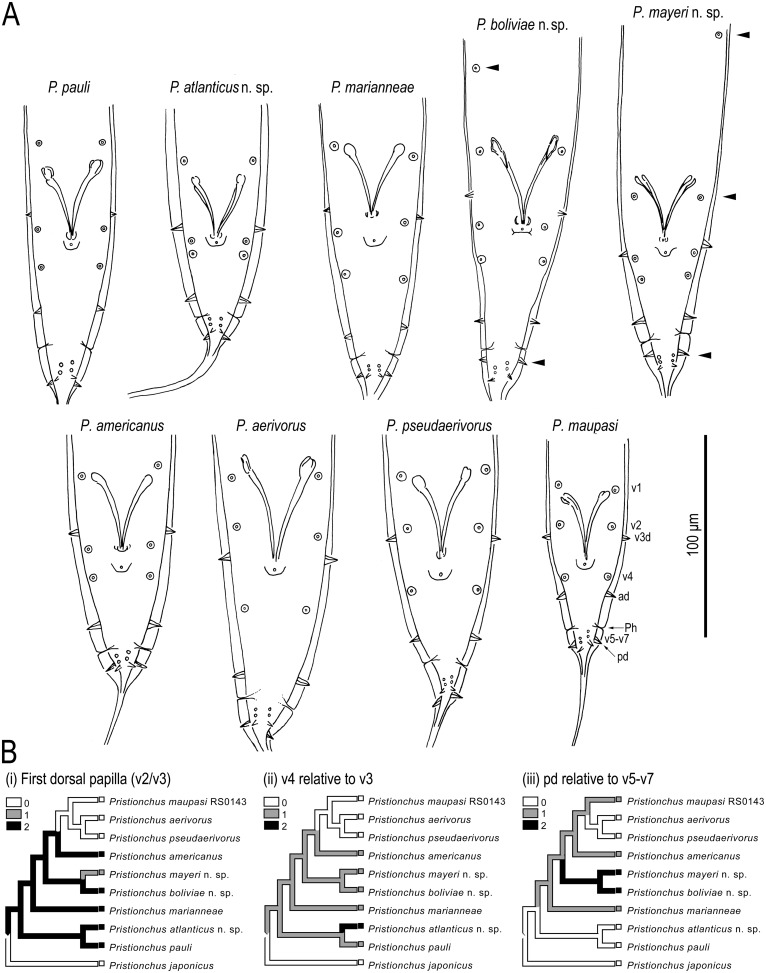

Informative male-specific characters in the maupasi group:

To further diagnose P. boliviae n. sp., P. mayeri n. sp., and P. atlanticus n. sp. with respect to other species in the maupasi group, we examined previously unreported characters of the male tail in P. americanus, P. marianneae, P. pauli, and P. pseudaerivorus, and provide new, comparable character information for P. aerivorus and P. maupasi (Fig. 12A). Species in the maupasi group were previously circumscribed based on reproductive isolation and molecular sequence divergence (Herrmann et al., 2006). Male papilla characters clearly separating these species by morphology include: positions of v2d and v3 relative to C; position of v4 relative to v3 and v2d; position of pd relative to v5–v7. Character states for the arrangement of papillae v1–v3 in gonochoristic taxa and P. maupasi are informative of the phylogenetic structure within the maupasi group (Fig. 12B). Specifically, the position of the second ventral papilla relative to the first dorsal papilla is posterior in the basal species of the group, P. pauli, P. marianneae, and P. americanus, whereas it is anterior in P. aerivorus, P. pseudaerivorus, and P. maupasi. In both P. boliviae n. sp. and P. mayeri n. sp., the most posterior dorsal papilla (pd) overlaps or is anterior to the three posterior ventral papillae (v5–v7). The papilla patterns in P. boliviae n. sp. and P. mayeri n. sp. are variable within the species, including inconsistent position and presence of v1, the inconsistent presence of an extra anterior papilla “v0,” the precise position of pd relative to v5–v7, and the absolute (but not relative) positions of v1–v4 in P. boliviae n. sp.

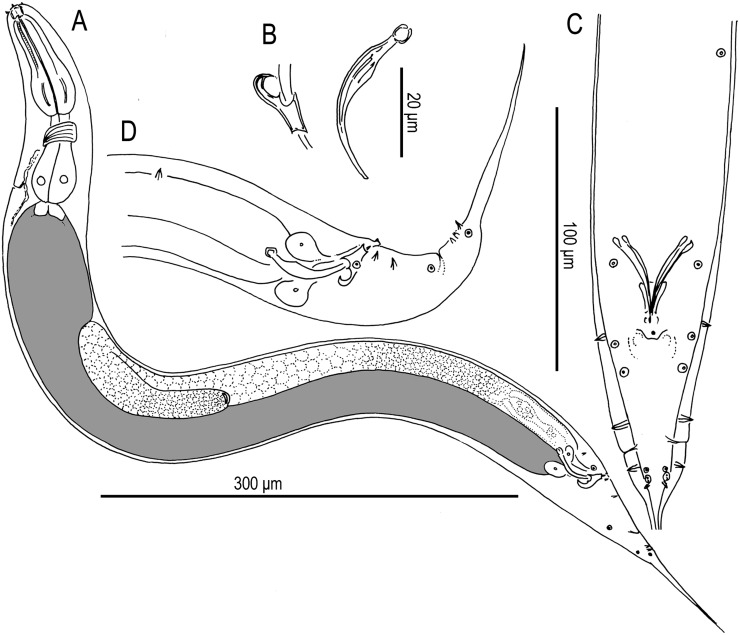

Fig. 12.

Diagnostic and phylogenetically informative male tail characters of the male tail of Pristionchus: A. Line drawings of genital papilla arrangement, shown in ventral view, in Pristionchus species of the maupasi group. Diagnostic characters include: opportunistic presence of “v0”; distance of v1 form v2/v3; relative positions of v2 and v3; positions of v2 and v3 relative to (C); position of pd relative to v5–v7; position of pd as variable. B. Ancestral state reconstruction of three male papilla characters in the maupasi group by simple parsimony, as implemented in Mesquite v.2.5 (Maddison and Maddison, 2011). Tree is from maximum likelihood analysis (Fig. 2). Characters and states are as follows: (i) identity of first dorsal papilla is v3 (0), v2/v3 (papillae are at same level) (1), or v2 (2); (ii) position of v4 relative to v3 is two-thirds to more than one cloacal body width or “far” (0), about one-half cloacal body width or “close” (1), or less than one-third cloacal body width or “very close” (2); (iii) most anterior position of pd relative to v5–v7 is posterior (0), overlapping (1), or anterior (2). Character states for outgroup, P. japonicus, are from Kanzaki et al. (2012a).

Of other valid Pristionchus species that have not been placed in a molecular phylogenetic context, P. vidalae (Stock, 1993) Sudhaus and Fürst von Lieven, 2003 has papillae arranged in an order similar to others in the maupasi group. This species, isolated from Diabrotica speciosa (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) in Argentina, shows a pattern of <v1, v2d, v3, C, v4, ad, [Ph], (v5, v6, v7), pd> (presumed phasmids were described as an extra pair of papillae), whereby v2d is far anterior to v3 and almost equidistant from v3 and v1, v4 is far anterior to ad and close to C, and ad is close to Ph. The arrangement in P. vidalae is thus closest to that of P. atlanticus n. sp. and P. americanus, and it is clearly distinguished from both species by the anterior positions of vd and presumed Ph. However, other morphological characters available for this species are presently insufficient to confidently place it in the maupasi group.

Discussion

Description of androdioecious species in a model system introduces a resource for comparative studies on the evolution of reproductive mode. Characterizing the new Pristionchus species by morphological and molecular phylogenetic evidence, including 27 gene loci in the present study, lays the necessary foundation for future work on these species as potential models. Increasing outgroup representation by description of the gonochoristic species P. atlanticus n. sp. gives greater resolution to tracking evolutionary events leading to androdioecy. Between the two closest species described herein, P. boliviae n. sp. and P. mayeri n. sp., molecular phylogenetic divergence was greater than that separating several other Pristionchus species pairs (Herrmann et al., 2006; Kanzaki et al., 2012a). Their identities as unique biological species were confirmed by their reproductive isolation in hybrid mating tests. Morphological characters further distinguish all three species.

Characters diagnostic of Pristionchus species:

Most morphological characters traditionally scored in Diplogastridae are invariant or vary to similar degrees within and across species of Pristionchus (Kanzaki et al., 2012a, 2012b; Fürst von Lieven and Sudhaus, 2000). In contrast, the morphology of the stoma, especially in the teeth and denticles, are often informative in characterizing Pristionchus species (Kanzaki et al., 2012a, 2012b), as they show topography complex enough to track minor differences by light microscopy. Within the maupasi group of species, however, much of this variability was also present within species, and so any particular denticle in the more complex arrangements cannot be reliably assigned a homologous state. Any variability of stomatal structures in Pristionchus species is therefore most useful for diagnosis in conjunction with other characters, especially those of the male sexual structures. A trait common to all three species and including other species in the maupasi group is the size of mouthparts, particularly the dorsal tooth, in the stenostomatous form (Ragsdale, unpubl. data). This tooth is typically large and often similar in size to the dorsal tooth of the eurystomatous form of the same species, although it is always flint-shaped and only sclerotized at the surface, as typical for the genus. Male genitalia, especially in the shape of the gubernaculum, were clearly distinct in all three new species. Arguably the most informative characters were in the arrangement of male genital papilla (Fig. 12). This interspecific variability, shown previously also for the pacificus group (Kanzaki et al., 2012a) and in more basal Pristionchus species (Kanzaki et al., 2012b), attests to the usefulness of these characters for diagnoses in the genus.

Divergence of male sexual structures in androdioecious species:

In contrast to gonochoristic species, the two new androdioecious species showed substantial variation in male sexual characters. In particular, the presence of an additional single lateral papilla or pair of papillae (“v0”) in P. boliviae n. sp. and P. mayeri n. sp. is unusual given the generally consistent number of nine papillae across the family (Sudhaus and Fürst von Lieven, 2003). The occasional appearance of an extra papilla was also observed in P. maupasi by Potts (1910), who noted increased variability in that androdioecious species compared with gonochorists. Furthermore, the position of pd in P. boliviae n. sp. and P. mayeri n. sp. varied with respect to the ventral v5–v7, sometimes assuming in both species a unique, anterior position (Figs. 5,8,9). Variability in papilla position was especially pronounced in P. boliviae n. sp., in which the absolute positions of v1–v4 were variable, with bilateral asymmetry common for v1, and in which a single ad papilla was even duplicated in one specimen. The inconsistency of male sexual characters in P. boliviae n. sp., P. mayeri n. sp., and apparently also P. maupasi (Potts, 1910), is in line with predictions of “selfing syndrome,” whereby mating-related traits become degenerate in males due to the reduced sexual selection pressure in a mostly self-fertilizing population (Thomas et al., 2012). In particular, the poor ability of males of P. boliviae n. sp. and P. mayeri n. sp. to cross in comparison with other Pristionchus species under similar experimental conditions (Herrmann et al., 2006) is consistent with the degeneracy of male sexual morphology in the former species. An extra, anterior male papilla has also been observed in the gonochoristic species Micoletzkya masseyi (Susoy et al., 2013) and Koerneria sp. (Kanzaki, unpubl. data), suggesting a latent propensity for this developmental aberration. The variable presence of “v0” and v1, as well as the intermediately located papillae in P. boliviae n. sp., raises the possibility that variability in v0 and v1 is linked to inappropriate cell division or apoptosis in the cell lineage of v1, the presumptive homolog of Rn.1 descendants in rhabditid nematodes (Fitch and Emmons, 1995).

Implications for the evolution of reproductive mode in Pristionchus:

The existence of two closely related androdioecious species raises the question of how common speciation and thus diversification is in taxa with a self-fertilizing reproductive mode. In Caenorhabditis nematodes, transitions to androdioecy have been recent events (Kiontke et al., 2004; Cutter et al., 2008). Because the accumulation of deleterious mutations is predicted to cause rapid extinction in purely asexual lineages (Muller, 1964), occasional outcrossing may have contributed to the persistence of androdioecious Pristionchus species as it has in Caenorhabditis (Loewe and Cutter, 2008). Is the sister relationship of the species P. boliviae n. sp. and P. mayeri n. sp. evidence that androdioecious species are not only evolutionarily stable, but capable of divergence? Based on taxon representation thus far, this is the most parsimonious scenario. Although uncommon, cladogenesis of androdioecious species is possible, as inferred for the rhabditid genus Oscheius (Felix et al., 2001; Kiontke and Fitch, 2005) and Eulimnadia clam shrimps (Weeks et al., 2006, 2009). Conversely, is sampling incomplete in this clade of Pristionchus, in which case the evolution of hermaphroditism would have arisen twice in closely related taxa? This prediction would be consistent with the observation that hermaphroditic species often exist in pairs with morphologically close gonochoristic species (i.e., “complemental species pairs” sensu Potts, 1908), presumably sharing recent common ancestry and possibly having speciated in sympatry (Osche, 1954). Ongoing efforts for denser taxon sampling will hopefully test whether closer gonochoristic sister species exist for P. boliviae n. sp. or P. mayeri n. sp. The empirically poor outcrossing ability of both of these species hints at the presence of incipient reproductive barriers within them, which if present in nature would facilitate speciation in these lineages. The capacity of some strains of P. boliviae n. sp. (strain RS5262) and P. mayeri n. sp. (RSA035) to produce high numbers of spontaneous males, for example, in comparison with P. pacificus (Click et al., 2009), may also have an impact on the population structure of these species.

In an alternative to androdioecy, many strains of P. entomophagus lack males altogether (Steiner, 1929) and cannot be made to induce them (D’Anna and Sommer, unpubl. data), including by incubation conditions that increase their incidence in androdioecious Caenorhabditis species (Hodgkin, 1999). The elimination of males from self-fertilizing strains would be consistent with the theoretical difficulties of maintaining androdioecy (Charlesworth, 1984; Pannell, 2002). However, the selection of androdioecy against males would also select for those that are successful outcrossers, which would explain why they are not completely lost in androdioecious nematode species (Chasnov, 2010). Therefore, the buildup of deleterious mutations or the inability to respond through recombination to strong selection pressure in obligate self-fertilizers of P. entomophagus would be predicted and thus suggests the recent evolution of hermaphroditism in this species. Achieving more thorough taxon representation in the entomophagus group will be a valuable step in testing this hypothesis.

Footnotes

The species epithet is the Latin genitive of Bolivia, the country of the type locality of this species.

This species is named in honor of our colleague Dr. Werner E. Mayer (deceased), whose work in the molecular systematics of Diplogastridae provided the necessary framework for comparative studies in Pristionchus.

The species epithet is a Latin adjective referring to the species' North American type locality near the Atlantic Ocean.

Literature Cited

- Charlesworth D. Androdioecy and the evolution of dioecy. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 1984;23:333–348. [Google Scholar]

- Chasnov JR. The evolution from females to hermaphrodites results in a sexual conflict over mating in androdioecious nematode worms and clam shrimp. Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 2010;23:539–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2009.01919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitwood BG. 1937. Cephalic structure and stoma. P. 53 in B. G. Chitwood and M. B. Chitwood, eds. Introduction to nematology. Baltimore: Monumental. [Google Scholar]

- Click A, Savaliya CH, Kienle S, Herrmann M, Pires-daSilva A. Natural variation of outcrossing in the hermaphroditic nematode Pristionchus pacificus. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2009;9:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutter AD, Wasmuth JD, Washington NL. Patterns of molecular evolution in Caenorhabditis preclude ancient origins of selfing. Genetics. 2008;178:2093–2104. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.085787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwin C. 1877. The different forms of flowers on plants of the same species. New York: Appelton. [Google Scholar]

- Denver DR, Clark KA, Raboin MJ. Reproductive mode evolution in nematodes: insights from molecular phylogenies and recently discovered species. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2011;61:584–592. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2011.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Research. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedorko A, Stanuszek S. Pristionchus uniformis sp. n. (Nematoda, Rhabditida, Diplogasteridae), a facultative parasite of Leptinotarsa decemlineata Say and Melolontha melolontha L. in Poland. Morphology and biology. Acta Parastiologica. 1971;19:95–112. [Google Scholar]

- Félix MA, Vierstraete A, Vanfleteren J. Three biological species closely related to Rhabditis (Oscheius) pseudodolichura Körner in Osche, 1952. Journal of Nematology. 2001;33:104–109. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch DHA, Emmons SW. Variable cell positions and cell contacts underlie morphological evolution of the rays in the male tails of nematodes related to Caenorhabditis elegans. Developmental Biology. 1995;170:564–582. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd R, Abebe E, Papert A, Blaxter M. Molecular barcodes for soil nematode identification. Molecular Ecology. 2002;11:839–850. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2002.01485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fürst von Lieven A. Koerneria sudhausi n. sp. (Nematoda: Diplogastridae); a hermaphroditic diplogastrid with an egg shell formed by zygote and uterine components. Nematology. 2008;10:27–45. [Google Scholar]

- Fürst von Lieven A, Sudhaus W. Comparative and functional morphology of the buccal cavity of Diplogastrina (Nematoda) and a first outline of the phylogeny of this taxon. Journal of Zoological Systematics and Evolutionary Research. 2000;38:37–63. [Google Scholar]

- Haag ES. Convergent evolution: Regulatory lightning strikes twice. Current Biology. 2009:R977–R979. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann M, Kienle S, Rochat J, Mayer WE, Sommer RJ. Haplotype diversity of the nematode Pristionchus pacificus on Réunion in the Indian Ocean suggests multiple independent invasions. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 2010;100:170–179. [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann M, Mayer WE, Sommer RJ. Sex, bugs and Haldane’s rule: The nematode genus Pristionchus in the United States. Frontiers in Zoology. 2006;3:14. doi: 10.1186/1742-9994-3-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin J. 1999. Conventional genetics. Pp. 245-270 in I. A. Hope, ed. C. elegans: A practical approach. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper DJ. 1986. Handling, fixing, staining and mounting nematodes. Pp. 59–80 in J. F. Southey, ed. Methods for work with plant and soil nematodes. London: Her Majesty’s Stationary Office. [Google Scholar]

- Kanzaki N, Ragsdale EJ, Herrmann M, Mayer WE, Sommer RJ. Description of three Pristionchus species (Nematoda: Diplogastridae) from Japan that form a cryptic species complex with the model organism P. pacificus. Zoological Science. 2012a;29:403–417. doi: 10.2108/zsj.29.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanzaki N, Ragsdale EJ, Herrmann M, Sommer RJ. Two new species of Pristionchus (Rhabditida: Diplogastridae): P. fissidentatus n. sp. from Nepal and La Réunion Island and P. elegans n. sp. from Japan. Journal of Nematology. 2012b;44:80–91. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiontke K, Fitch DHA. 2005. The phylogenetic relationships of Caenorhabditis and other rhabditids. (August 11, 2005). The C. elegans Research Community, ed. WormBook. doi/10.1895/wormbook.1.11.1. [Google Scholar]

- Kiontke K, Gavin NP, Raynes Y, Roehrig C, Piano F, Fitch DHA. Caenorhabditis phylogeny predicts convergence of hermaphroditism and extensive intron loss. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:9003–9008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403094101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiontke K, Manegold A, Sudhaus W. Redescription of Diplogasteroides nasuensis Takaki, 1941 and D. magnus Völk, 1950 (Nematoda: Diplogastrina) associated with Scarabaeidae (Coleoptera) Nematology. 2001;3:817–832. [Google Scholar]

- Kreis HA. Beiträge zur Kenntnis pflanzenparasitischer Nematoden. Zeitschrift für Parasitenkunde. 1932;5:184–194. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis SC, Dyal LA, Hilburn CF, Weitz S, Liau WS, LaMunyon CW, Denver DR. Molecular evolution in Panagrolaimus nematodes: Origins of parthenogenesis, hermaphroditism and the Antarctic species P. davidi. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2009;9:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-9-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewe L, Cutter AD. On the potential for extinction by Muller’s Ratchet in Caenorhabditis elegans. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2008;8:125. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maddison WP, Maddison DR. 2011. Mesquite: A modular system for evolutionary analysis. Version 2.75. URL: http://mesquiteproject.org. [Google Scholar]

- Maupas E. Essais d’hybridation chez les nématodes. Bulletin Biologique de la France et de la Belgique. 1919;52:466–498. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer WE, Herrmann M, Sommer RJ. Phylogeny of the nematode genus Pristionchus and implications for biodiversity, biogeography and the evolution of hermaphroditism. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2007;7:104. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer WE, Herrmann M, Sommer RJ. Molecular phylogeny of beetle associated diplogastrid nematodes suggests host switching rather than nematode-beetle coevolution. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2009;9:212. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-9-212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JH, Ford AL. Life history and habits of two new nematodes parasitic in insects. Journal of Agricultural Research. 1916;6:115–127. [Google Scholar]

- Micoletzky H. Die freilebenden Erd-Nematoden. Archiv für Naturgeschichte. Abteiliung A. 1922;87:1–650. [Google Scholar]

- Muller HJ. The relation of recombination to mutational advance. Mutation Research. 1964;1:2–9. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(64)90047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osche G. Über die gegenwärtig ablaufende Entstehung von Zwillings- und Komplementärarten bei Rhabditiden (Nematodes). Zoologische Jahrbücher. Abteilung für Systematik. 1954;82:618–654. [Google Scholar]

- Pannell JR. The evolution and maintenance of androdioecy. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 2002;33:397–425. [Google Scholar]

- Paramonov AA. Opyt ekologicheskoi klassifikatsii fitonematod. Trudy Gelmintologicheskii Laboratorii. Akademia Nauk SSSR (Moskva) 1952;6:338–369. [Google Scholar]

- Pires-da Silva A, Sommer RJ. Conservation of the global sex determination gene tra-1 in distantly related nematodes. Genes & Development. 2004;18:1198–1208. doi: 10.1101/gad.293504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts FA. Sexual phenomena in the free-living nematodes. Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. 1908;14:373–375. [Google Scholar]

- Potts FA. Notes on the free-living nematodes. Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science. 1910;55:433–484. [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F, Teslenko M, van der Mark P, Ayres DL, Darling A, Höhna S, Larget B, Liu L, Suchard MA, Huelsenbeck JP. MrBayes 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Systematic Biology. 2012;61:539–542. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/sys029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer RJ. The future of evo-devo: Model systems and evolutionary theory. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2009;10:416–422. doi: 10.1038/nrg2567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sommer RJ, Carta LK, Kim SY, Sternberg PW. Morphological, genetic and molecular description of Pristionchus pacificus n. sp. (Nematoda: Neodiplogastridae) Fundamental and Applied Nematology. 1996;19:511–521. [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. RAxML-VI-HPC: Maximum likelihood-based analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2688–2690. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner G. Diplogaster entomophaga n. sp., a new Diplogaster (Diplogasteridae, Nematodes) found on a Pamphilius stellatus (Christ) (Tenthredinidae, Hymenoptera) Zoologischer Anzeiger. 1929;80:143–145. [Google Scholar]

- Stock SP. Micoletzkya vidalae n. sp. (Nematoda: Diplogasteridae), a facultative parasite of Diabrotica speciosa (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) from Argentina. Research and Reviews in Parasitology. 1993;53:109–112. [Google Scholar]

- Sudhaus W, Fürst von Lieven A. A phylogenetic classification and catalogue of the Diplogastridae (Secernentea, Nematoda) Journal of Nematode Morphology and Systematics. 2003;6:43–90. [Google Scholar]

- Susoy V, Kanzaki N, Herrmann M. Description of the bark beetle associated nematodes Micoletzkya masseyi n. sp. and M. japonica n. sp. (Nematoda: Diplogastridae) Nematology. 2013;15:213–231. [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas CG, Woodruff GC, Haag ES. Causes and consequences of the evolution of reproductive mode in Caenorhabditis nematodes. Trends in Genetics. 2012;28:213–220. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Völk J. Die Nematoden der Regenwürmer und aasbesuchenden Käfer. Zoologische Jahrbücher. Abteilung für Systematik. 1950;79:1–70. [Google Scholar]

- Weeks SC. The role of androdioecy and gynodioecy in mediating evolutionary transitions between dioecy and hermaphroditism in the Animalia. Evolution. 2012;66:3670–3686. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2012.01714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks SC, Chapman EG, Rogers DC, Senyo DM, Hoeh WR. Evolutionary transitions among dioecy, androdioecy and hermaphroditism in limnadiid clam shrimp (Branchiopoda: Spinacaudata) Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 2009;22:1781–1799. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2009.01813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeks SC, Sanderson TF, Reed SK, Zofkova M, Knott B, Balaraman U, Pereira G, Senyo DM, Hoeh WR. Ancient androdioecy in the freshwater crustacean Eulimnadia. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B. 2006;273:725–734. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2005.3370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weingärtner I. Versuch einer Neuordnung der Gattung Diplogaster Schulze 1857 (Nematoda). Zoologische Jahrbücher. Abteilung für Systematik. 1955;83:248–317. [Google Scholar]