Abstract

The current study is an extension of our previous study where we tested the protective efficacy of gp63 and Hsp70 against murine visceral leishmaniasis. The cocktail vaccine was combined with MPL-A and ALD adjuvants and the protection afforded by the three vaccines was compared. Inbred BALB/c mice were immunized twice at an interval of two weeks with the vaccine formulations. Two weeks after the booster, they were challenged with 107 promastigotes of Leishmania donovani and sacrificed on 30, 60 and 90 days post infection/challenge. The protective efficacy of vaccines was analyzed by assessment of the hepatic and splenic parasite burden and generation of cellular and humoral immune responses. The immunized animals revealed a significant reduction in parasite burden as compared to the infected controls. These animals also showed heightened DTH response, increased generation of IgG2a, IFN-γ and IL-2 by spleen cells. This was also accompanied by a decrease in the levels of IgG1 and IL-10. Mice immunized with gp63+Hsp70+MPL-A exhibited significantly greater protection in comparison to those immunized with gp63+Hsp70+ALD.

Keywords: Visceral leishmaniasis, Vaccine, gp63, Hsp70, MPL-A, ALD

Introduction

Tropical parasitic diseases remain an important health concern in underdeveloped countries. Kinetoplastid parasites of the genus Leishmania generate a variety of pathologies collectively termed leishmaniasis, afflicting millions of people worldwide (Ashford et al. 1992; Banuls et al. 2007). Three major clinicopathological categories are recognized: cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL), muco-cutaneous leishmaniasis (MCL) and visceral leishmaniasis (VL) each caused by distinct species. VL is a clinical affliction that affects around 50,000 people globally every year. Leishmania parasites are among the best candidates for the development of safe and effective vaccines against their infection since, in vertebrate hosts, the parasite has a single morphological form, the amastigote that does not undergo genetic variation and is responsible for the pathology in the mammalian host, and has a single target host cell, the macrophage (Pearson et al. 1983). Leishmania parasites escape from the humoral response by hiding as amastigotes inside the phagolysosomes of host macrophages, therefore circulating antibodies have little or no effect on the infection. So, cell-mediated immunity plays a major role in protection against the parasite (Sukumaran and Madhubala 2004). Considerable effort has been made to develop a vaccine to induce specific anti-parasitic immune responses. The first recombinant antigen used to vaccinate against leishmaniasis was leishmanolysin or gp63 (Handman 2001). It plays a central role in a number of host cell molecular events that likely contribute to the infectivity of Leishmania (Halle et al. 2009). Because of the abundance of gp63 and its ability to mediate resistance against infectious promastigotes, gp63 has been suggested as a candidate for vaccination against Leishmania infection (Handman et al. 1990; Nascimento et al. 1990). In fact, the first recombinant antigen used to vaccinate against leishmaniasis was leishmanolysin or gp63 (Handman 2001). The recombinant form of gp63 (rgp63) expressed in E. coli conferred partial protection in the vervet monkey host (Olobo et al. 1995). Furthermore, murine dendritic cells (DC), when loaded with gp63 as antigen, enhanced the capability to control the parasite burden (Berberich et al. 2003). The antigen when encapsulated in liposomes has been shown to afford significant protection against murine VL and CL (Jaafari et al. 2006). In a recent study, BLAST cladogram and phylogenetic tree analysis shed light on the fact that a high level of conservation and identity amongst gp63 residues may help in the designing of a common vaccine against VL caused by different species of Leishmania (Sinha et al. 2011).

Many of the immunogenic Leishmania antigens are members of conserved protein families such as heat-shock proteins (Hsps) (MacFarlane et al. 1990; Skeiky et al. 1995). One of the Hsps, Hsp70 from Leishmania major has not been found protective in murine models of CL and stimulates strong humoral responses in cutaneous and VL patients. The humoral immune responses against the different truncated forms of Hsp70 suggested a mixed Th1/Th2 response in vivo (Rafati et al. 2007). In an earlier study, gp63 DNA vaccine and polytope DNA vaccines fused with Hsp70 have been shown to be immunogenic (Sachdeva et al. 2009). Recently, in our laboratory we tested the protective efficacy of cocktail vaccine comprising of gp63 and Hsp70 (Kaur et al. 2011b). The vaccine formulation imparted significant protection against L. donovani, however the protection afforded was not complete. In our previous studies, we observed that addition of autoclaved Leishmania donovani (ALD) and monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL-A) as adjuvants to 78 kDa antigen and cocktail vaccine of Hsp70 and Hsp83 increased significantly the level of protection imparted by these vaccine formulations in VL infected mice (Nagill and Kaur 2010; Kaur et al. 2011a). Therefore, to further strengthen the immunogenicity of the cocktail vaccine of gp63 and Hsp70, in the current study, we added two adjuvants MPL-A and ALD and compared the level of protection afforded by them.

Materials and methods

Parasite strain

The MHOM/IN/80/Dd8 strain of L. donovani, originally obtained from London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, was used for the present study and maintained in vitro at 22 ± 1 °C in RPMI-1640 with 10 % foetal calf serum (FCS).

Animals

Inbred BALB/c mice of either sex, weighing 20–25 g, were obtained from the Central Animal House of Panjab University, Chandigarh. They were kept in germ free environment and fed with water and mouse feed ad libitum.

Ethical clearance

The ethical clearance for conducting the experiments was obtained from the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee, Panjab University, Chandigarh, India.

Identification and electroelution of proteins

The parasite proteins were run on SDS-PAGE gels (miniVE vertical electrophoresis system, Amersham, USA) by the method of Laemmli (1970). The proteins were also localized by 2-D gel electrophoresis in a previous study (Kaur et al. 2011b). After staining and destaining the gel, the bands of interest were taken in the electrophoresis buffer (0.025 M Tris, 0.192 M glycine, 1 % SDS) in electro-eluter and a constant voltage of 50 V for 5–6 min was applied through the gel. After elution, the proteins were dialyzed and suspended in PBS (pH 7.2) and were quantified (Lowry et al. 1951).

Preparation of various vaccine formulations

Based on gp63 and Hsp70, three types of vaccines were prepared in the present study. The cocktail vaccine of gp63 and Hsp70 was prepared as described previously (Kaur et al. 2011b). The antigens were formulated with two adjuvants: autoclaved L. donovani antigen (ALD) and MPL-A (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). The ALD adjuvant was prepared by autoclaving the parasite suspension (108 per ml) at 15 lbs for 30 min and the protein content was quantified (Lowry et al. 1951). The gp63+Hsp70+ALD vaccine was prepared by mixing 250 μg of eluted proteins with 2.5 mg of ALD antigen while gp63+Hsp70+MPL-A vaccine was prepared by the addition of 100 μl solution of MPL-A (conc. 10 mg/ml) to 250 μg of the eluted proteins.

Immunization and infection of mice

BALB/c mice were immunized by subcutaneous injections of 10 μg of gp63 and Hsp70 along with MPL-A or ALD. Two injections were given at an interval of 2 weeks. Animals receiving only PBS served as controls (Normal and Infected). Two weeks after the booster, the immunized and infected controls were challenged intracardially with 107 log phase promastigotes.

Assessment of parasite load

Six animals from each group were sacrificed on 30, 60 and 90 days post infection/challenge. Liver and spleen of all animals were removed and weighed. Impression smears of liver and spleen were made and the parasite load was assessed in terms of Leishman Donovan Units (LDU) by the method of Bradley and Kirkley (1977).

DTH responses to leishmanin

48 h before the day of sacrifice, all groups of mice were challenged in right and left foot pad with a subcutaneous injection of leishmanin (prepared in PBS) and PBS respectively (Kaur et al. 2008). Before sacrificing the animals (that is, on 30, 60 and 90 days post infection/challenge), the thickness of right and left foot pad was measured using a pair of Vernier callipers. Results were expressed as mean ± SD of percentage increase in the thickness of the right foot pad as compared to the left footpad of mice.

ELISA for parasite-specific IgG1 and IgG2a isotypes

The specific serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) isotype antibody response was measured by conventional ELISA using commercially available kits (Bangalore Genei, India). Crude antigen (10 μg/well) was prepared by harvesting log phase promastigotes from the culture, freeze thawed (6 cycles) and then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm at 4 °C. The supernatant was collected, estimated for protein concentration and used for coating the 96-well ELISA plates. Serum samples were added at twofold serial dilutions, followed by addition of isotype specific HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (rabbit anti-mouse IgG1 or IgG2a) after which the H2O2 substrate and DAB chromogen were added and absorbance was read on an ELISA plate reader at 450 nm.

Determination of vaccine-induced cytokine production

For cytokine assay, cell suspensions were made by tearing the spleen in MEM. The dish was kept undisturbed for 5 min and the supernatant was taken out carefully and then centrifuged at 1,500 rpm for 15 min. To lyse the erythrocytes, 4 ml of 0.85 % ammonium chloride was added to the pellet, thoroughly mixed with care and kept on ice for 20 min. After that the pellet was centrifuged at 1,500 rpm for 15 min. This whole procedure was repeated until white pellet of lymphocytes was obtained. The lymphocytes isolated from spleens of mice were cultured in 24 well plates in 1 ml of RPMI-1640 containing 20 mM NaHCO3, 10 mM HEPES, 10 U/ml of penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, 2 mM l-glutamine and 10 % FCS. Cells were stimulated with 50 μg/ml of gp63+Hsp70. Cells were then incubated at 37 °C for 72 h and supernatant was collected and stored at −20 °C. This was then assayed for IL-2, IL-10 and IFN-γ by using ELISA kits (BenderMed Systems, Diaclone). All the experiments were performed three times independently. The data comparisons were tested for significance using SPSS software. Two-way comparison between all the groups was performed using Student’s t test while the multiple comparisons amongst different groups were performed by analysis of variance (ANOVA). P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Parasite load

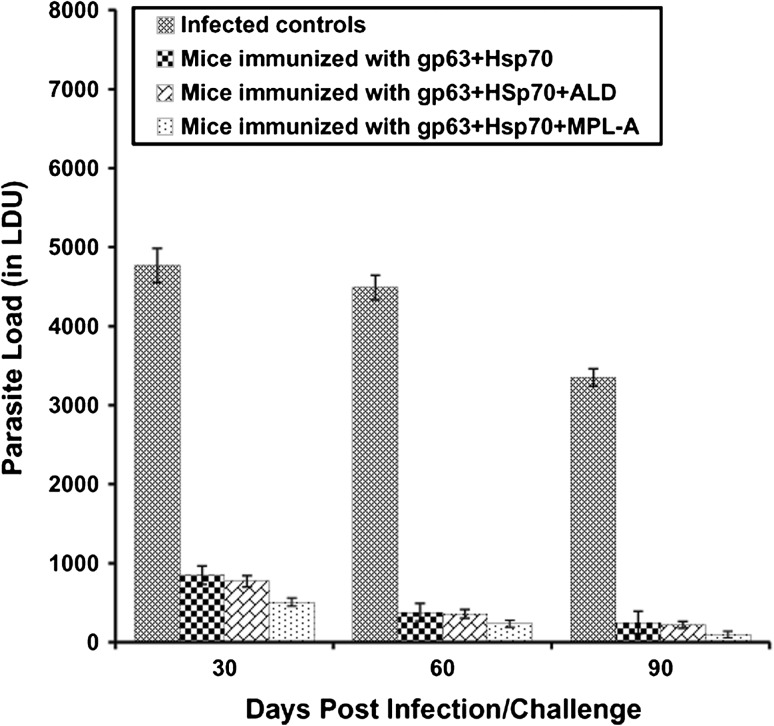

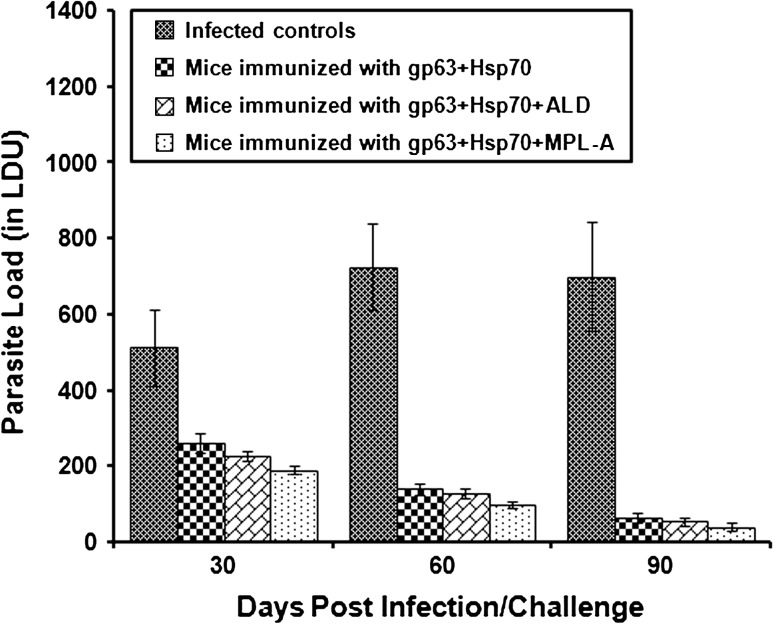

The parasite burden in liver and spleen was calculated in all groups of mice on 30, 60 and 90 days post infection/challenge and was measured in terms of LDU. The immunized animals revealed significantly (p < 0.05) lesser parasite load in comparison to the infected controls. Parasite load in liver increased significantly in infected control BALB/c mice on different post infection days. In contrast, in the immunized animals, the parasite load declined significantly (p < 0.05) from 30 to 90 days post infection. In the animals immunized with a cocktail vaccine of gp63 and Hsp70, the parasite load declined by 82.21–92.61 % as compared to the infected controls from 30 to 90 days post infection. When the animals were immunized with the cocktail vaccine along with two different adjuvants-MPL-A and ALD, the level of protection increased significantly (p < 0.05). Animals immunized with gp63+Hsp70 in combination with ALD showed a reduction of 83.84–93.51 % in the parasite load while least parasite load was observed in animals immunized with both the antigens in combination with MPL-A. The decline in parasite load in this group of animals was 89.37–97.13 % as compared to the infected controls (Fig. 1). The combination of gp63 and Hsp70 caused 49.19–90.66 % reduction in splenic parasite load as compared to the infected controls. With the addition of ALD to the cocktail vaccine, the level of protection increased from 55.67–92.32 %. Furthermore, when the vaccine was used along with MPL-A, the decline in parasite load was 63–94.35 %. Among all the immunized groups, the difference in LDU was found to be significant (p < 0.001) on all days post challenge (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Hepatic parasite load in terms of LDU in the liver of BALB/c mice immunized with different vaccine formulations as seen on different days post challenge

Fig. 2.

Splenic parasite load in terms of LDU in the liver of BALB/c mice immunized with different vaccine formulations as seen on different days post challenge

Delayed type hypersensitivity (DTH) responses

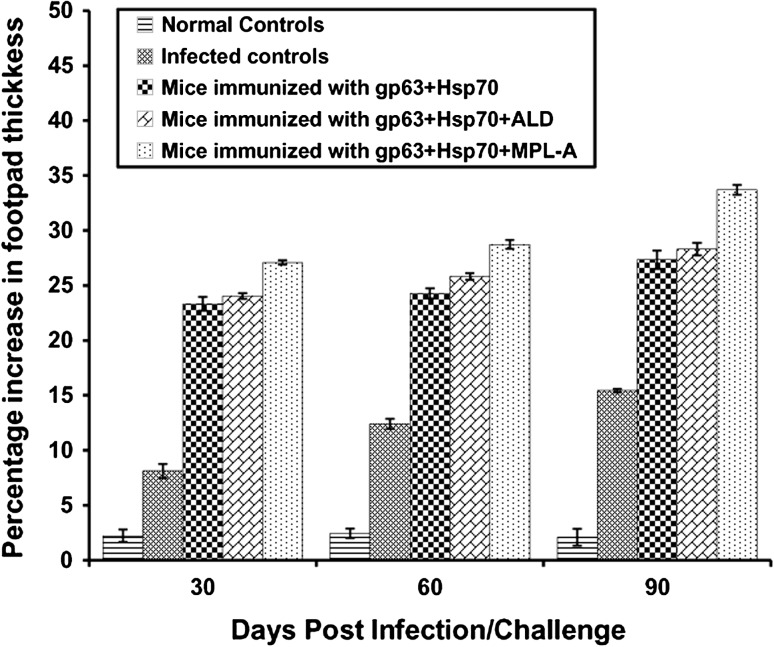

The DTH responses were measured as an index of cell-mediated immune responses. In all the groups of animals, the DTH responses increased significantly from 30 to 90 days post infection. However, the immunized animals revealed significantly (p < 0.05) higher DTH responses in comparison to the infected controls. Immunization of animals with gp63+Hsp70 along with MPL-A antigen induced the highest level of DTH response followed by those immunized with gp63+Hsp70+ALD and gp63+Hsp70 (Fig. 3). The difference in the DTH responses of the animals immunized with the antigens in combination with ALD and MPL-A was significant (p < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

DTH responses on different days post challenge in BALB/c mice immunized with different vaccine formulations

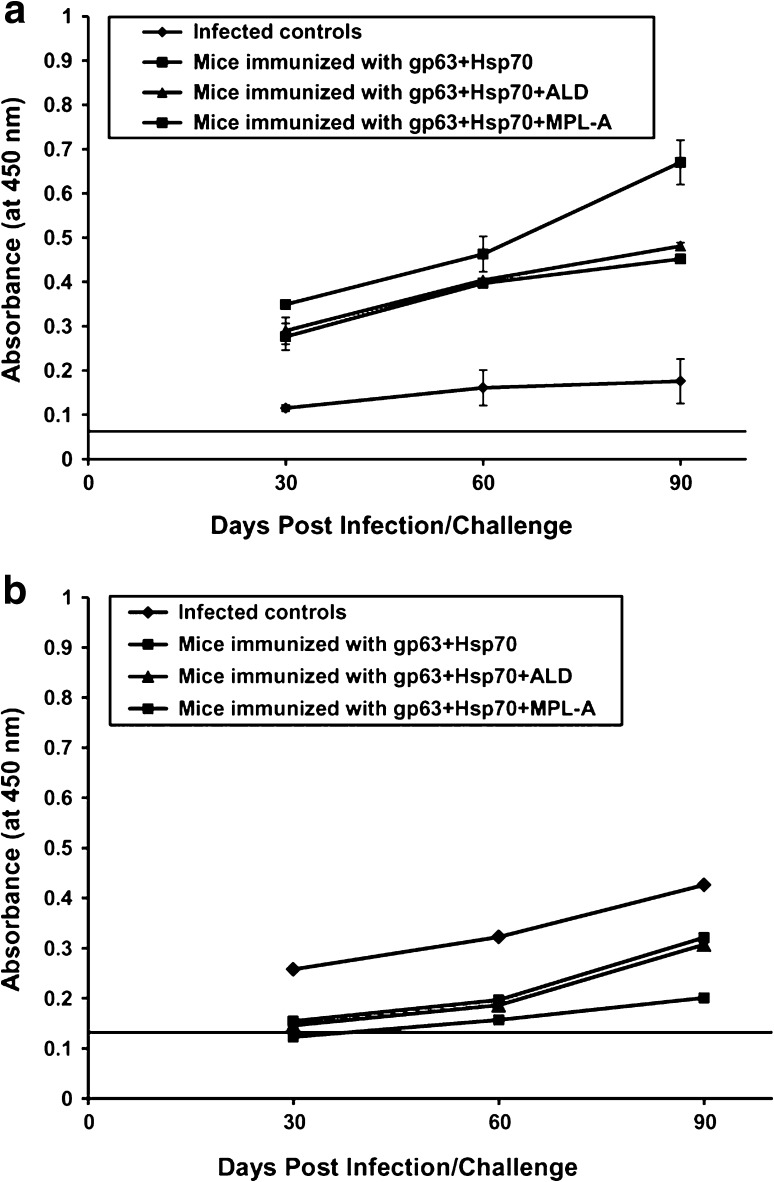

Specific antibody responses

The humoral response to gp63+Hsp70+MPL-A and gp63+Hsp70+ALD was characterized by analyzing the distribution of IgG1 and IgG2a specific antibodies in the sera of immunized and control animals. In all the groups of animals, IgG1 and IgG2a antibody responses were evaluated in the serum samples by ELISA using specific anti-mouse isotype antibodies. Immunized animals showed higher IgG2a and lower IgG1 antibody levels in comparison to the infected controls. The maximum levels of IgG2a antibody were observed in the mice immunized with gp63+Hsp70+MPL-A. The gp63+Hsp70+ALD recipient mice also produced significant levels of IgG2a antibody (Fig. 4a). In contrast to the IgG2a levels, the immunized animals revealed significantly (p < 0.05) lesser IgG1 levels as compared to the infected controls. The animals immunized with gp63+Hsp70 in combination with adjuvants (ALD or MPL-A) revealed significantly (p < 0.05) reduced IgG1 levels as compared to those immunized with gp63+Hsp70. Minimum IgG1 levels were observed in the animals immunized with gp63+Hsp70+MPL-A (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

Levels of Leishmania-specific antibodies (a IgG2a, b IgG1) in serum samples on different days post challenge in BALB/c mice immunized with different vaccine formulations

Cytokine responses

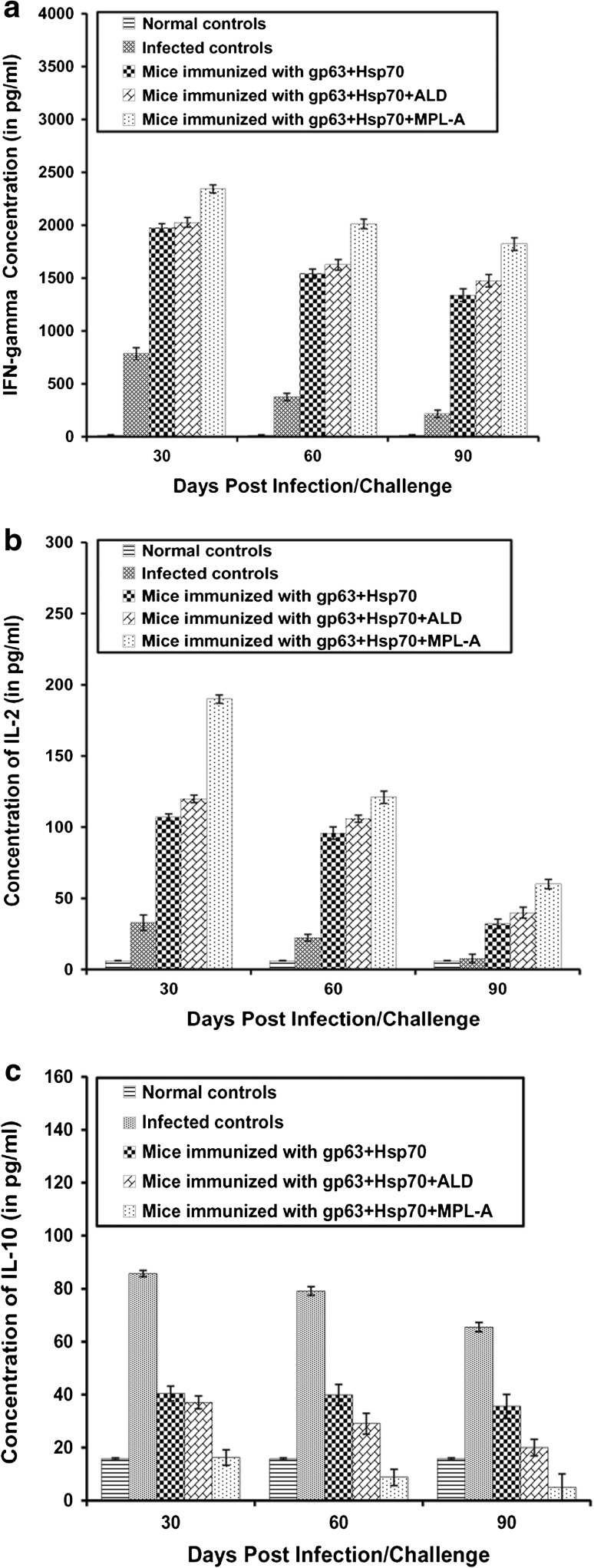

The immune response (Th1 or Th2) generated by various vaccine formulations was assessed by quantifying the cytokines (IFN-γ, IL-2 and IL-10) produced by splenocytes of vaccinated animals. The concentration of Th1 specific cytokines, that is, IFN-γ and IL-2 were significantly (p < 0.05) higher in the immunized mice as compared to the infected controls. Maximum concentrations of these cytokines were observed in animals immunized with the combination of gp63 and Hsp70 along with MPL-A. As compared to this group, the mice immunized with gp63+Hsp70+ALD showed significantly (p < 0.05) lesser concentration of these cytokines. Least concentration of these cytokines was observed in the animals immunized with the antigens alone (Fig. 5a, b). The levels of Th2 regulated cytokine IL-10 were significantly (p < 0.05) lesser in immunized animals as compared to the infected controls. Maximum levels of this cytokine were observed in the infected controls. Animals immunized with gp63+Hsp70+MPL-A showed least concentration of IL-10. As compared to above group animals immunized with gp63+Hsp70+ALD showed slightly elevated levels of IL-10 (Fig. 5c).

Fig. 5.

Concentration of cytokines (a IFN-γ, b IL-2, c IL-10) in the supernatants of cultures of splenocytes incubated with gp63 and Hsp70 cocktail. The splenocytes were prepared from spleen collected on different days post challenge in BALB/c mice immunized with different vaccine formulations

Discussion

Currently, the drugs used in leishmaniasis treatment present several problems, including high toxicity and many adverse effects, leading to patients withdrawing from treatment and emergence of resistant strains. In addition, the high cost of these compounds makes the treatment far from suitable and, regrettably, it has been increasing gradually throughout the years (Yardley et al. 2002; Singh and Sivakumar 2004).Till date, no cost effective control for leishmaniasis exists. Therefore, the development of a safe, effective and affordable vaccine would seem to offer the only real solution for controlling leishmaniasis. An increasing number of Leishmania molecules with potential for vaccine development are being identified (Requena et al. 2004). Earlier in our laboratory, we showed that the cocktail vaccine of gp63 and Hsp70 antigens imparted significant protection in L. donovani infected BALB/c mice (Kaur et al. 2011b).

The ultimate goal of vaccination is to generate a strong immune response which confers long lasting protection against leishmaniasis. As purified protein antigens are poor immunogens, they require the addition of an adjuvant or antigen-carrier system to be effective. MPL-A has been recognized as potent immunostimulator and is able to induce humoral as well as cell-mediated immune response when used along with antigen. MPL-A has been safely used as a vaccine adjuvant in animal models and in human clinical trials against several infectious diseases and has been effective in shifting immune responses of some antigens from a Th2-dominant to a Th1-dominant response (Evans et al. 2003). The potential of autoclaved antigen of L. donovani to induce cell-mediated and humoral response has also been evaluated and results indicate that it has potential as a vaccine which could trigger cell-mediated immune response (Nagill et al. 2009). Therefore in the present study the immunoprophylactic potential of gp63+Hsp70 along with adjuvants MPL-A and ALD has been assessed. The protective efficacy of vaccines was assessed by the percentage reduction in the parasite load in liver and immunogenicity was assessed through the detection of DTH response, production of anti-leishmanial antibodies (IgG1 and IgG2a) and cytokines such as IFN-γ, IL-2 and IL-10.

In the present study, immunization of mice with gp63+Hsp70+MPL-A and gp63+Hsp70+ALD conferred significant protection against a progressive infection with L. donovani. The gp63+Hsp70+MPL-A vaccine significantly protected the BALB/c mice against L. donovani infection and reduced the parasite load in liver by 97.13 % and in spleen by 94.35 %. The results are in consistence with previous studies which showed that addition of monophosphoryl lipid plus squalene emulsion (MPL-SE) to a cocktail vaccine (containing H1, HASPB1 and MML) or Leish-110f conferred partial or significant protection in dogs against VL respectively (Moreno et al. 2007; Miret et al. 2008). Experimental infection of immunized mice and hamsters have demonstrated that Leish-111f+MPL-SE induced significant protection against L. infantum infection, with reduction in parasite loads up to 99.6 % (Coler et al. 2007). Also, the use of ALD as an adjuvant along with gp63+Hsp70 antigen significantly protected the BALB/c mice against Leishmania infection and reduced the parasite load by 85.7 %. This is in agreement to the studies which showed that vaccination with autoclaved L. major conferred significant protection in simian and mice (Dube et al. 1998; Misra et al. 2001; Michel et al. 2006) while ALD has been shown to confer protection in hamster model (Srivastava et al. 2003). Immunization with autoclaved Leishmania antigen has been shown to induce a significant resistance to challenge infection in mice as observed by reduction in parasite load (Nagill et al. 2009). In contrast, autoclaved L. major along with BCG did not induce significant protective immune response in humans against VL (Khalil et al. 2000). Taken together, our results confirmed that both vaccine formulations imparted protection in mice against a progressive infection with L. donovani however the degree of protection varied with the adjuvant used. As seen by reduction in parasite load, protection imparted by MPL-A was more effective than gp63+Hsp70+ALD suggesting that MPL-A is more superior as an adjuvant in comparison to ALD. This is in correspondence to our previous studies where MPL-A was more effective in increasing the protective efficacy of 78 kDa antigen and cocktail of Hsp70+Hsp83 as compared to ALD (Nagill and Kaur 2010; Kaur et al. 2011a).

The humoral response to gp63+Hsp70+MPL-A and gp63+Hsp70+ALD was characterized by analyzing the distribution of IgG1 and IgG2a specific antibodies in the sera of immunized and control animals. ELISA results show that immunized groups developed higher level of antibody responses than control animals. The IgG1 response is an indicator of Th2 type of immune response and IgG2a antibody response corresponds to Th1 response which is protective. Among the two immunized groups, the highest IgG1 response was induced in mice immunized with gp63+Hsp70+ALD followed by gp63+Hsp70+MPL-A. In contrast, the IgG2a antibody production was found to be maximum in mice immunized with gp63+Hsp70+MPL-A followed by mice immunized with gp63+Hsp70+ALD and infected controls. It indicates that MPL-A is more protective and effective in generating Th1 response as compared to ALD. Previous studies have also shown that mice immunized with autoclaved antigen preferentially induce type 1 immune response (Nagill et al. 2009). Moreover, immunization with 78 kDa +MPL-A and Hsp70+Hsp83+MPL-A has been shown to significantly increase the production of IgG2a response (Nagill and Kaur 2010; Kaur et al. 2011a).Vaccination with Leish-111f+MPL-SE has been shown to increase antibody titers indicating a targeted immune response (Trigo et al. 2010).

A typical DTH reaction is characterized by activation and recruitment predominantly of T cells and macrophages at the site of intradermal injection in previously sensitized host (Black 1999). Peak DTH responses were observed in animals which were immunized with a combination of gp63+Hsp70+MPL-A and these were followed by animals immunized with a combination of gp63+Hsp70+ALD. The efficacy of gp63+Hsp70 antigen along with MPL-A was superior to that of ALD in generating DTH response. These immunized groups were followed by infected and normal controls suggesting that immunized mice developed a strong cell-mediated immune response and thereby resisted the challenge by parasites. The results demonstrated a positive correlation between enhanced DTH response and reduced parasite load for all groups. Our results are in agreement with the studies which showed that mice immunized with autoclaved and heat killed antigen of L. donovani elicited strong DTH response correlated with the protection against infection in these groups (Nagill et al. 2009). Similarly monkeys vaccinated with ALM+rIL-12 has been shown to elicit higher DTH responses (Gicheru et al. 2001). Our studies are also in consistence with the studies which showed that MPL-A when used along with 78 kDa antigen for immunization further enhanced the DTH response (Nagill and Kaur 2010). Also, MPL-A significantly elicited the DTH responses as compared to ALD when given with Hsp70+Hsp83 prior to L. donovani infection in BALB/c mice (Kaur et al. 2011a).

The immune response (Th1 or Th2) generated by various vaccine formulations was assessed by quantifying the cytokines (IFN-γ, IL-2 and IL-10) produced by splenocytes of vaccinated animals. Mice immunized with gp63+Hsp70+MPL-A showed greater concentration of IFN-γ, the Th1 specific cytokine in comparison to mice immunized with gp63+Hsp70+ALD followed by control animals. High levels of IFN-γ indicate the development of a protective Th1 immune response. This IFN-γ is found to come from natural killer cells and is thought to play an important role as a component of innate immune mechanism for the activation of macrophages (Nylen et al. 2003). Immunization of animals significantly increased the concentration of IL-2 in comparison to the infected controls. Similarly, the IL-2 levels were also found to be maximum in animals immunized with gp63+Hsp70+MPL-A followed by mice immunized with gp63+Hsp70+ALD and then control animals suggesting that MPL-A is more efficient in generating Th1 type of immune response as characterized by enhanced IFN-γ and IL-2 production in comparison to ALD. IL-2 plays a critical role in priming naive CD4+ T cells to become IL-4 or IFN-γ producers (Seder et al. 1994) and it is a principal T cell growth factor for Th1 type of immune response. In contrast, IL-10 response was found to be maximum in infected control animals but declined significantly in mice immunized with gp63+Hsp70+ALD followed by mice immunized with gp63+Hsp70+MPL-A. IL-10 represents the main macrophage-deactivating cytokine and plays an important regulatory role in the progression of VL (Tripathi et al. 2007). Our results are in consistence with those obtained from murine leishmaniasis model of both cutaneous and visceral diseases where expression of IFN-γ is associated with control of infection (Heinzel et al. 1989; Squires et al. 1989). Studies on cytokine profiles in canine VL have established the predominance of the Leishmania-specific Th1 response in asymptomatic dogs and the role of IFN-γ as the key cytokine involved in the activation of macrophages and the killing of the intracellular amastigotes (Carrillo and Moreno 2009). Our results are also in correspondence with the studies which showed that mice immunized with 78 kDa antigen +MPL-A significantly brought down the IL-4 and IL-10 levels in immunized mice. Production of these cytokines was also suppressed to some extent in 78 kDa+ALD immunized mice (Nagill and Kaur 2010). Studies have also shown that immunization with Leish-111f+MPL-SE protected mice and hamsters against L. infantum infection that correlated with induction of Th1 immune response as characterized with production of IFN-γ, TNF, IL-2 with little IL-4 (Coler et al. 2007). High levels of IL-10 in infected control animals supported the view that upregulation of this cytokine is accompanied by disease progression and depressed Th1 type of cell-mediated immunity with decreased production of IFN-γ and IL-12 (Carvalho et al. 1989; Ghalib et al. 1993). Previous studies have also confirmed that IL-10 suppresses Th1 response, which plays a protective role against active VL (Carvalho et al. 1994). Moreover studies have shown that IL-10 gene deficient mice are resistant to L. donovani infection and produce more IFN-γ and IL-12 (Murphy et al. 2001). These results are in accordance with our previous studies where animals immunized with Hsp70+Hsp83+MPL-A induced maximum levels of IFN-γ, IL-2 and minimum levels of IL-10 when compared with the mice immunized with Hsp70+Hsp83+ALD and Hsp70+Hsp83 (Kaur et al. 2011a).

Thus it can be concluded that both vaccine formulations i.e. gp63+Hsp70+MPL-A and gp63+Hsp70+ALD were found to be protective in terms of reduction in parasite load, good DTH response, production of anti-leishmanial antibodies and upregulation of cytokine production by splenocytes of immunized BALB/c mice. Both of them conferred best protection and induced Th1 mediated cellular immune responses in mice against L. donovani infection. However, vaccine formulation composed of gp63+Hsp70+MPL-A was found to be more effective than gp63+Hsp70+ALD in terms of efficient reduction in parasite load, increased DTH response and enhanced production of IgG2a, IFN-γ and IL-2.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the financial support rendered by Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), India under Ref No: 5 / 8-7(77) / 2006-ECD-II.

References

- Ashford RW, Desjeux P, Deraadt P. Estimation of population at risk of infection and number of cases of Leishmaniasis. Parasitol Today. 1992;8:104–105. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(92)90249-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banuls AL, Hide M, Prugnolle F. Leishmania and the leishmaniases: a parasite genetic update and advances in taxonomy, epidemiology and pathogenicity in humans. Adv Parasitol. 2007;64:1–109. doi: 10.1016/S0065-308X(06)64001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berberich C, Ramirez-Pineda JR, Hambrecht C, Alber G, Skeiky YA, Moll H. Dendritic cell (DC)-based protection against an intracellular pathogen is dependent upon DC-derived IL-12 and can be induced by molecularly defined antigens. J Immunol. 2003;170:3171–3179. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.3171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black CA. Delayed-type hypersensitivity: current theories with an historic perspective. Dermatol Online J. 1999;5:7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley DJ, Kirkley J. Regulation of Leishmania populations within host I. the variable course of Leishmania donovani infections in mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 1977;30:119–129. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo E, Moreno J. Cytokine profiles in canine visceral leishmaniasis. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2009;128:67–70. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2008.10.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho EM, Bacellar O, Barral A, Badaro R, Johnson WD., Jr Antigen-specific immunosuppression in visceral leishmaniasis is cell mediated. J Clin Investig. 1989;83:860–864. doi: 10.1172/JCI113969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho EM, Bacellar O, Brownell C, Regis T, Coffman R, Reed SG. Restoration of IFN-gamma production and lymphocyte proliferation in visceral leishmaniasis. J Immunol. 1994;152:5949–5956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coler RN, Goto Y, Bogatzki L, Raman V, Reed SG. Leish-111f, a recombinant polyprotein vaccine that protects against visceral leishmaniasis by elicitation of CD4+ T cells. Infect Immun. 2007;75:4648–4654. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00394-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube A, Sharma P, Srivastava JK, Misra A, Naik S, Katiyar JC. Vaccination of langur monkeys (Presbytis entellus) against Leishmania donovani with autoclaved L. major plus BCG. Parasitology. 1998;116:219–221. doi: 10.1017/S0031182097002175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JT, Cluff CW, Johnson DA, Lacy MJ, Persing DH, Baldridge JR. Enhancement of antigen-specific immunity via the TLR4 ligands MPL adjuvant and Ribi.529. Exp Rev Vaccines. 2003;2:219–229. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghalib HW, Piuvezam MR, Skeiky YA, Siddig M, Hashim FA, El-Hassan AM, Russo DM, Reed SG. Interleukin 10 production correlates with pathology in human Leishmania donovani infections. J Clin Investig. 1993;92:324–329. doi: 10.1172/JCI116570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gicheru MM, Olobo JO, Anjili CO, Orago AS, Modabber F, Scott P. Vervet monkeys vaccinated with killed Leishmania major parasites and Interleukin-12 develop a type 1 immune response but are not protected against challenge infection. Infect Immun. 2001;69:245–251. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.1.245-251.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halle M, Gomez MA, Stuible M, Shimizu H, McMaster WR, Olivier M, Tremblay ML. The Leishmania surface protease GP63 cleaves multiple intracellular proteins and actively participates in p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase inactivation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:6893–6908. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805861200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handman E. Leishmaniasis: current status of vaccine development. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14:229–243. doi: 10.1128/CMR.14.2.229-243.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handman E, Button LL, McMaster RW. Leishmania major: production of recombinant gp63, its antigenicity and immunogenicity in mice. Exp Parasitol. 1990;70:427–435. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(90)90127-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinzel FP, Sadick MD, Holaday BJ, Coffman RL, Locksley RM. Reciprocal expression of interferon gamma or interleukin 4 during the resolution or progression of murine leishmaniasis: evidence for expansion of distinct helper T cell subsets. J Exp Med. 1989;169:59–72. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaafari MR, Ghafarian A, Farrokh-Gisour A, Samiei A, Kheiri MT, Mahboudi F, Barkhordari F, Khamesipour A, McMaster WR. Immune response and protection assay of recombinant major surface glycoprotein of Leishmania (rgp63) reconstituted with liposomes in BALB/c mice. Vaccine. 2006;24:5708–5717. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.04.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur S, Kaur T, Garg N, Mukherjee S, Raina P, Athokpam V. Effect of dose and route of inoculation on the generation of CD4+ Th1/Th2 type of immune response in murine visceral leishmaniasis. Parasitol Res. 2008;103:1413–1419. doi: 10.1007/s00436-008-1150-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur J, Kaur T, Kaur S. Studies on the protective efficacy and immunogenicity of Hsp70 and Hsp83 based vaccine formulations in Leishmania donovani infected BALB/c mice. Acta Trop. 2011;119:50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur T, Sobti RC, Kaur S. Cocktail of gp63 and Hsp70 induces protection against L. donovani in BALB/c mice. Parasite Immunol. 2011;33:95–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2010.01253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil EAG, El Hassan AM, Zijlstra EE, Mukhtar MM, Ghalib HW, Musa B, Ibrahim ME, Kamil AA, Elsheikh M, Babiker A, Modabber F. Autoclaved Leishmania major vaccine for prevention of visceral leishmaniasis: a randomised, double-blind, BCG-controlled trial in Sudan. Lancet. 2000;356:1565–1569. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randal RJ. Protein measurement with the folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacFarlane J, Blaxter ML, Bishop RP, Miles MA, Kelly JM. Identification and characterisation of a Leishmania donovani antigen belonging to the 70-kDa heat-shock protein family. Eur J Biochem. 1990;190:377–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel MY, Fathy FM, Hegazy EH, Hussein ED, Eissa MM, Said DE. The adjuvant effects of IL-12 and BCG on autoclaved Leishmania major vaccine in experimental cutaneous leishmaniasis. J Egypt Soc Parasitol. 2006;36:159–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miret J, Nascimento E, Sampaio W, Franca JC, Fujiwara RT, Vale A, Dias ES, Vieira E, da Costa RT, Mayrink W, Campos-Neto A, Reed S. Evaluation of an immunochemotherapeutic protocol constituted of N-methyl meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime) and the recombinant Leish-110f+MPL-SE vaccine to treat canine visceral leishmaniasis. Vaccine. 2008;26:1585–1594. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misra A, Dube A, Srivastava B, Sharma P, Srivastava JK, Katiyar JC, Naik S. Successful vaccination against Leishmania donovani infection in Indian langur using alum-precipitated autoclaved Leishmania major with BCG. Vaccine. 2001;19:3485–3492. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(01)00058-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno J, Nieto J, Masina S, Canavate C, Cruz I, Chicharro C, Carrillo E, Napp S, Reymond C, Kaye PM, Smith DF, Fasel N, Alvar J. Immunization with H1, HASPB1 and MML Leishmania proteins in a vaccine trial against experimental canine leishmaniasis. Vaccine. 2007;25:5290–5300. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy ML, Wille U, Villegas EN, Hunter CA, Farrell JP. IL-10 mediates susceptibility to Leishmania donovani infection. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:2848–2856. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(2001010)31:10<2848::AID-IMMU2848>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagill R, Kaur S. Enhanced efficacy and immunogenicity of 78 kDa antigen formulated in various adjuvants against murine visceral leishmaniasis. Vaccine. 2010;28:4002–4012. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagill R, Mahajan R, Sharma S, Kaur S. Induction of cellular and humoral responses by autoclaved and heat-killed antigen of Leishmania donovani in experimental visceral leishmaniasis. Parasitol Int. 2009;58:359–366. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento E, Mayrink W, da Costa CA, Michalick MS, Melo MN, Barros GC, Dias M, Antunes CM, Lima MS, Taboada DC. Vaccination of humans against cutaneous leishmaniasis: cellular and humoral immune responses. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2198–2203. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.7.2198-2203.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylen S, Maasho K, Soderstrom K, Ilg T, Akuffo H. Live Leishmania promastigotes can directly activate primary human natural killer cells to produce interferon-gamma. Clin Exp Immunol. 2003;131:457–467. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02096.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olobo JO, Anjili CO, Gichero MM, Mbati PA, Kariuki TM, Githure JI, Koech DE, McMaster WR. Vaccination of vervet monkeys against cutaneous leishmaniosis using recombinant Leishmania major surface glycoprotein (gp63) Vet Parasitol. 1995;60:199–212. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(95)00788-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson RD, Wheeler DA, Harrison LH, Kay HD. The immunobiology of leishmaniasis. Rev Infect Dis. 1983;5:907–926. doi: 10.1093/clinids/5.5.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rafati S, Gholami E, Hassani N, Ghaemimanesh F, Taslimi Y, Taheri T, Soong L. Leishmania major heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) is not protective in murine models of cutaneous leishmaniasis and stimulates strong humoral responses in cutaneous and visceral leishmaniasis patients. Vaccine. 2007;25:4159–4169. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Requena JM, Iborra S, Carrion J, Alonso C, Soto M. Recent advances in vaccines for leishmaniasis. Exp Opin Biol Ther. 2004;4:1505–1517. doi: 10.1517/14712598.4.9.1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachdeva R, Banerjea AC, Malla N, Dubey ML. Immunogenicity and efficacy of single antigen gp63, polytope and polytope Hsp70 DNA vaccines against visceral leishmaniasis in experimental mouse model. PLoS ONE. 2009 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seder RA, Germain RN, Linsley PS, Paul WE. CD28-mediated costimulation of interleukin 2 (IL-2) production plays a critical role in T cell priming for IL-4 and interferon gamma production. J Exp Med. 1994;179:299–304. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.1.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Sivakumar R. A gp63 based vaccine candidate against visceral leishmaniasis. J Infect Chemother. 2004;10:307–315. doi: 10.1007/s10156-004-0348-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha S, Sundaram S, Singh AP, Tripathi A. A gp63 based vaccine candidate against visceral leishmaniasis. Bioinformation. 2011;5:320–325. doi: 10.6026/97320630005320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skeiky YA, Benson DR, Guderian JA, Whittle JA, Bacelar O, Carvalho EM, Reed SG. Immune responses of leishmaniasis patients to heat shock proteins of Leishmania species and humans. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4105–4114. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.10.4105-4114.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squires KE, Schreiber RD, McElrath MJ, Rubin BY, Anderson SL, Murray HW. Experimental visceral leishmaniasis: role of endogenous IFN-gamma in host defense and tissue granulomatous response. J Immunol. 1989;143:4244–4249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava JK, Misra A, Sharma P, Srivastava B, Naik S, Dube A. Prophylactic potential of autoclaved Leishmania donovani with BCG against experimental visceral leishmaniasis. Parasitology. 2003;127:107–114. doi: 10.1017/S0031182003003457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sukumaran B, Madhubala R. Leishmaniasis: current status of vaccine development. Curr Mol Med. 2004;4:667–669. doi: 10.2174/1566524043360203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trigo J, Abbehusen M, Netto EM, Nakatani M, Pedral-Sampaio G, de Jesus RS, Goto Y, Guderian J, Howard RF, Reed SG. Treatment of canine visceral leishmaniasis by the vaccine Leish-111f+MPL-SE. Vaccine. 2010;28:3333–3340. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.02.089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripathi P, Singh V, Naik S. Immune response to Leishmania: paradox rather than paradigm. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2007;51:229–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2007.00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yardley V, Khan AA, Martin MB, Slifer TR, Araujo FG, Moreno SN, Docampo R, Croft SL, Oldfield E. In vivo activities of farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase inhibitors against Leishmaniadonovani and Toxoplama gondii. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:929–931. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.3.929-931.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]