Abstract

Achalasia is a neurodegenerative motility disorder of the oesophagus resulting in deranged oesophageal peristalsis and loss of lower oesophageal sphincter function. Historically, annual achalasia incidence rates were believed to be low, approximately 0.5-1.2 per 100000. More recent reports suggest that annual incidence rates have risen to 1.6 per 100000 in some populations. The aetiology of achalasia is still unclear but is likely to be multi-factorial. Suggested causes include environmental or viral exposures resulting in inflammation of the oesophageal myenteric plexus, which elicits an autoimmune response. Risk of achalasia may be elevated in a sub-group of genetically susceptible people. Improvement in the diagnosis of achalasia, through the introduction of high resolution manometry with pressure topography plotting, has resulted in the development of a novel classification system for achalasia. This classification system can evaluate patient prognosis and predict responsiveness to treatment. There is currently much debate over whether pneumatic dilatation is a superior method compared to the Heller’s myotomy procedure in the treatment of achalasia. A recent comparative study found equal efficacy, suggesting that patient preference and local expertise should guide the choice. Although achalasia is a relatively rare condition, it carries a risk of complications, including aspiration pneumonia and oesophageal cancer. The risk of both squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus is believed to be significantly increased in patients with achalasia, however the absolute excess risk is small. Therefore, it is currently unknown whether a surveillance programme in achalasia patients would be effective or cost-effective.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Achalasia, Incidence, Treatment, Oesophageal cancer risk

Core tip: Achalasia remains a disease of unknown aetiology. Multicentre studies could help elucidate the cause, especially as it presents with a similar phenotype to Chagas disease which is much better understood. Improved understanding of aetiology could guide novel treatments. Current treat choice in fit patients lies between pneumatic dilatation and laparoscopic Heller’s myotomy. Botulinum toxin is appropriate and effective for those unfit for other intervention. Novel treatments such as metal stents and natural orifice surgery are being trialled.

INTRODUCTION

Achalasia is a motility disorder of the oesophagus, of unknown aetiology, which results in degeneration of the myenteric nerve plexus of the oesophageal wall. The resultant abnormalities and diagnostic characteristics of achalasia include loss of oesophageal peristalsis and failure of relaxation of the lower oesophageal sphincter, particularly during swallowing[1].

DIAGNOSIS

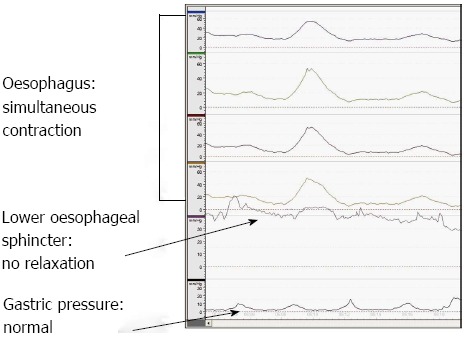

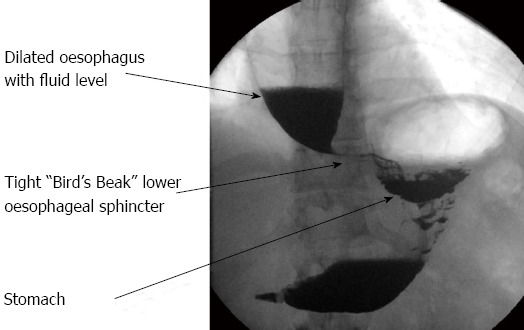

Dysphagia is the cardinal symptom of achalasia. Diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion and exclusion of other causes. Diagnosis is confirmed by manometric, endoscopic and radiographic investigations. Oesophageal manometry is regarded as the gold standard in the diagnosis of achalasia, classically showing aperistalsis and failure of relaxation of the lower oesophageal sphincter[2], as shown in Figure 1. Endoscopy is not accurate in the diagnosis of achalasia. However, it is still necessary to exclude a carcinoma at the lower end of the oesophagus[3]. Barium esophagogram can often show the pathognomonic “bird’s beak” appearance of the distal oesophagus with dilatation of the oesophagus proximally (Figure 2). However, this is often a finding in established disease and therefore a normal barium swallow does not rule out the diagnosis of achalasia. With the introduction of high resolution manometry, together with pressure topography, plotting the diagnosis of achalasia can now be classified into three subtypes; type 1 classic achalasia, type 2 achalasia with compression and pressurisation effects, and type 3 spastic achalasia[4]. This classification process can aid treatment decisions, with type 2 achalasia being the most responsive to pneumatic dilatation, Hellers myotomy and botulinum toxin and therefore having the best outcome[5]. Oesophageal emptying is determined by the distensibility of the oesophago-gastric junction. This can be assessed using an endoscopic functional luminal imaging probe (EndoFLIP). Recently, Dutch and American groups have demonstrated that this novel technique is a better predictor than lower oesophageal sphincter pressure for assessing response to treatment in achalasia, both symptomatically and when measured by gastric emptying by oesophageal emptying[6,7].

Figure 1.

Oesophageal manometry demonstrating simultaneous contractions within the oesophagus and a non-relaxing lower oesophageal sphincter.

Figure 2.

Barium swallow demonstrating typical “bird’s-beak” appearance of the lower oesophageal sphincter in achalasia. The oesophagus above this is dilated.

PATHOGENESIS

The pathogenesis of achalasia is not well understood but it is believed to be due to an inflammatory neurodegenerative insult with possible viral involvement. The measles and herpes viruses have been suggested as candidate viruses however molecular techniques have failed to confirm these claims and therefore the causative agent remains undiscovered[8]. Genetic and autoimmune components have also been suggested as origins of the neuronal damage however research to date has not found the exact cause[9]. Inflammatory changes within the oesophagus following the causative insult result in the loss of postganglionic inhibitory neurons in the myenteric plexus and a consequent reduction in the inhibitory transmitters, nitric oxide and vasoactive intestinal peptide. The excitatory neurons remain unaffected, with the resulting imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory neurons preventing lower oesophageal sphincter relaxation[10]. Lack of peristalsis and a non-relaxing lower oesophageal sphincter cause progressive dysphagia. Regurgitation, particularly at night, with aspiration of undigested food and weight loss can be presenting features, particularly in established disease. Features which present in the early stages of the disease may be similar to that of gastro-oesophageal reflux, including retrosternal chest pain typically after eating and heartburn[11]. Due to initial non-specific symptoms in early stage disease and the low prevalence of achalasia worldwide, the condition often goes undiagnosed for many years, giving rise to features of late stage disease and their associated complications.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

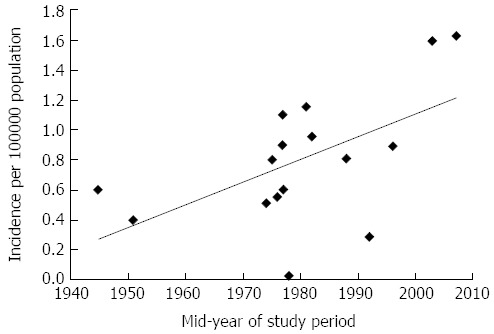

Achalasia is a relatively rare condition. A summary of studies published to date on achalasia incidence and prevalence is shown in Table 1[12-25]. The incidence of achalasia varied between studies, with reports as low as 0.03/100000 per year in Zimbabwe[22] to 1.63/100000 per year in Canada[14]. The majority of incidence rates reported clustered between 0.5-1.2 per 100000/year (Table 1). In an attempt to investigate changing incidence rates over time, we plotted incidence rates against the mid-timepoint within the study periods (Figure 3). As shown in Figure 3, incidence rates of achalasia appear to be rising, with most reports since the 1980s exceeding rates of 0.8/100000 per year, which has doubled to 1.6/100000 per year in post-2000 studies. Whether this reflects a true rise in incidence, or greater awareness and improved diagnosis of the condition remains uncertain though.

Table 1.

Summary of epidemiological studies of achalasia incidence and prevalence in adults

| Study | Location | Years studied | Total number of achalasia patients | Prevalence rate (per 100000) | Incidence rate (per 100000/year) |

| Howard et al[12] | Edinburgh, Scotland | 1986-1991 | Not reported | Not reported | 0.81 |

| Birgisson et al[13] | Iceland | 1952-2002 | 62 | 8.7 | 0.55 |

| Sadowski et al[14] | Alberta, Canada | 1995-2008 | 463 | 2.518 | Not reported |

| 10.829 | 1.639 | ||||

| Mayberry et al[15] | Great Britain and Ireland | 1972-1983 | 6306 | Not reported | Not reported |

| Scotland | 583 | 11.2 | 1.1-1.26 | ||

| Wales | 197 | 7.1 | Not reported | ||

| Northern Ireland | 153 | 9.8 | Not reported | ||

| Republic of Ireland | 453 | 13.4 | Not reported | ||

| England | 4920 | 10.8 | 0.97 | ||

| Mayberry et al[16] | Cardiff, Wales | 1926-1977 | 48 | Not reported | 0.4 |

| Mayberry et al[17] | Nottingham, England | 1966-1983 | 53 | 8.0 | 0.51 |

| Arber et al[18] | Israel | 1973-1983 | 162 | 7.91 | 0.83 |

| 12.62 | 1.154 | ||||

| Earlam et al[19] | Rochester, United States | 1925-1964 | 11 | Not reported | 0.6 |

| Galen et al[20] | Virginia, United States | 1975-1980 | 31 | Not reported | 0.6 |

| Mayberry et al[21] | New Zealand | 1980-1984 | 152 | Not reported | 1.0 |

| Stein et al[22] | Zimbabwe | 1974-1983 | 25 | Not reported | 0.03 |

| Farrukh et al[23] | Leicester, England | 1986-2005 | 14 | Not reported | 0.895 |

| Ho et al[24] | Singapore | 1989-1996 | 49 | 1.77 | 0.29 |

| Gennaro et al[25] | Veneto, Italy | 2001-2005 | 365 | Not reported | 1.59 |

Rate in 1973 only;

Rate in 1983 only;

Rate between 1973-1978;

Rate between 1979-1983 only;

Rate only applicable for South Asian population of region;

Rate reported as 1.1 for men and 1.2 for women;

Rate only applicable to Oxford region of England;

Rate in 1996 only;

Rate in 2007 only.

Figure 3.

Achalasia incidence by mid-study time points.

There are no distinct patterns of achalasia incidence in terms of age and sex distribution; it can affect both genders, all races and all ages[26]. A few studies have suggested a bimodal distribution of incidence by age, with peaks at around age 30 and 60 years[12,18,24], while others have pointed towards a generally increased risk of achalasia with increased age[15,23,25]. Achalasia appears to affect males and females to largely equal extents[12,13,15,18,21,23-25,27] although some investigations have detected slightly higher rates amongst females[16,19,28]. Only one study reported a higher achalasia incidence in men[14]. A study carried out by Mayberry et al[15] found achalasia to be significantly more common in the Republic of Ireland in comparison to its neighbouring countries (Table 1). Similarly, a study which reviewed the incidence of achalasia in New Zealand found differing incidence between ethnic groups[21]. The Pacific Islanders had an incidence of 1.3/100000 per year in comparison to those of Maori descent having an incidence of 0.2/100000 per year. This may reflect the influence of genetic factors in achalasia aetiology[21].

A Canadian population-based study also considered the prevalence and survival rates of patients with achalasia[14]. Sadowski et al[14] found that the prevalence of achalasia rose from 2.51/100000 in 1996 to 10.82/100000 in 2007, despite a relatively stable incidence over the same time period (Table 1). The rise in prevalence was seen in both genders but was noted to be more pronounced in males, reflecting the fact that achalasia is a slowly progressive disease. This rise in prevalence was also evident in an Israeli study[18] and was noted in an Icelandic study between 1952 and 2002[13]. It is interesting to note that the Canadian study observed survival of achalasia patients to be significantly lower than the age-sex matched control population[14]. However, others have discerned that the majority of deaths in achalasia patients result from unrelated causes, leading to an equivalent life expectancy to the general population[29].

AETIOLOGY

There has been much debate over the aetiology of achalasia, with several potential triggers for the inflammatory destruction of inhibitory neurons in the oesophageal myenteric plexus being implicated. These include autoimmune responses, infectious agents and genetic factors.

Auto-immune conditions

One recent study observed that patients with achalasia were 3.6 times more likely to suffer an autoimmune condition, compared with the general population[30]. Sjogren’s syndrome, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus and uveitis were all significantly more prevalent in achalasia patients. The study also found the presence of a T-cell infiltrate and antibodies within the myenteric plexus of many patients with achalasia and an increased presence of human leukocyte antigen class II antigens[30]. Another study noted an overall higher prevalence of neural autoantibodies in patients with achalasia in comparison with a healthy control group[31]. Although no specific autoantibody was identified, this further supports the theory that achalasia has an autoimmune basis[31].

Infectious agents

The role of an infectious agent in the development of achalasia has been widely debated with several viral agents being implicated. For example, Chagas disease has a known infectious aetiology, and exhibits many similarities with achalasia[32]. In addition, there are several reports of varicella zoster virus and Guillain-Barre syndrome preceding the onset of achalasia[32]. Antibody studies have demonstrated increased titres to herpes and measles viruses in patients with achalasia in comparison to healthy control groups[33,34]. One study looking specifically at the link between the herpes simplex virus (HSV) and primary achalasia indicated the presence of HSV-1 reactive immune cells in the lower oeseophageal sphincter of achalasia patients, suggesting that HSV-1 may be involved in the neuronal damage to the myenteric plexus leading to achalasia[35]. A further study of peripheral blood immune cells found that patients with achalasia showed an enhanced response to HSV-1 antigens[34]. In contrast, another investigation using PCR on myotomy specimens did not find any association between herpes, measles or human papilloma viruses and achalasia[36]. The current evidence for a causative infectious agent is contradictory and no clear causal relationship has yet been established.

Genetic predisposition

The genetic basis for achalasia has not been widely investigated due to its low prevalence. One syndrome, known as the triple “A” syndrome, which consists of a triad of achalasia, alacrima and adrenocorticotrophic hormone resistant adrenal insufficiency is a known autosomal recessive disorder caused by gene mutations on chromosome 12. This syndrome, together with the prevalence of cases within children of consanguineous couples[37], suggests the possibility for a genetic component to the aetiology of achalasia. There have been associations with other genetic diseases including Parkinson’s disease, Downs syndrome and MEN2B syndrome[10]. One recent suggested the possibility of involvement of the rearranged during transfection gene, which is a major susceptibility gene for Hirschprung’s disease (also linked with Down’s syndrome)[9]. Mayberry et al[38] conducted a study of first degree relatives of achalasia patients but concluded that inheritance was unlikely to be a significant causative factor due to the rarity of familial cases and exposure to common environmental and social factors within a family group may explain the presence of familial cases of achalasia.

It has been postulated that achalasia may incorporate a multi-factorial aetiology with an initiating event such as a viral or environmental insult resulting in oesophageal myenteric plexus inflammation. This inflammatory reaction may then initiate an autoimmune response in a susceptible group of genetically predisposed people, causing destruction of inhibitory neurons[39].

TREATMENT

The mainstay of treatment for achalasia is either pneumatic balloon dilatation or laparoscopic myotomy[40]. In pneumatic balloon dilatation, a balloon is positioned across the lower oesophageal sphincter and inflated, effectively rupturing the muscle of the affected segment. Surgical myotomy can be performed as either an open or laparoscopic procedure. The laparoscopic technique is now the most commonly performed. The procedure involves making a longitudinal division of the circular muscle of the lower oesophageal sphincter, extending this both proximally and distally onto the cardia[11]. Many surgeons advise the use of an anti-reflux procedure together with surgical myotomy, as these patients at are an increased risk of reflux following surgery[3]. A recent study compared partial anterior and partial posterior fundoplication following cardiomyotomy. It concluded that partial posterior fundoplication was superior to the anterior procedure due to significantly lower reintervention rates for postoperative dysphagia[41].

The best comparative study between pneumatic dilatation and surgery to date has demonstrated remarkably similar outcomes in matched patients over a three year follow up period[42]. Therapeutic success at two years was noted in 86% of those treated by pneumatic dilatation and 90% of those who had laparoscopic Heller’s myotomy. The regimen for pneumatic dilatation was rigorous with the option of multiple dilatations. The accompanying editorial suggests that choice should be determined by patient preference and local expertise[43]. A new endoscopic esophagomyotomy technique has been recently introduced: Peroral endoscopic myotomy involves dividing the inner circular muscle of the oesophagus. This requires sophisticated expertise and remains experimental[39].

In patients for whom invasive procedures are not suitable, alternative treatment options may be considered including pharmacological intervention using long-acting nitrates and calcium channel blockers. However, these are of limited benefit[44]. A further option is botulinum toxin injection into the lower oesophageal sphincter. This technique offers good short term results[45]. Most recently, metal stents have been used successfully[46]. Both of these options are generally only suited to those with several co-morbidities[9].

COMPLICATIONS

Patients with achalasia are at risk of developing the complications associated with disease progression as well as its treatment interventions. The complications of achalasia that can develop as a result of the natural course of the condition include aspiration-pneumonia[47]. Megaesophagus develops in 10% of inadequately treated cases and can ultimately require oesophagectomy[48].

Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common oesophageal cancer in patients with achalasia and this is thought to result from the high level of nitrosamines produced by bacterial overgrowth due to stasis in the oesophagus leading to chronic inflammation and dysplasia[49]. There is considerable variation in the documented oesophageal cancer risk in achalasia. One review found that the prevalence of oesophageal cancer in achalasia was 3%, corresponding to a 50-fold increased risk[50], while a prior review reported increased risks ranging from 0-33-fold greater than the general population[51]. Subsequent reports would also indicate a slightly more modest, but still significantly elevated, risk of oesophageal cancer 16-28-times greater than an age-sex matched control population[52,53].

The risk of oesophageal adenocarcinoma is also increased in those with achalasia and may be a complication of longstanding reflux following successful interventional treatment[27,54]. A recent publication from The Netherlands demonstrated that 8.2% of 331 primary achalasia patients developed Barrett’s oesophagus over a period of up to 25 years[55]. Two of these Barrett’s cases progressed to develop oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Other studies have also reported elevated risks of Barrett’s oesophagus and oesophageal adenocarcinoma in achalasia patients[27,56].

A few studies have described even larger increased risks of oesophageal cancer amongst achalasia patients. One German study reported an risk of developing oesophageal cancer up to 140 times greater in patients with achalasia than the normal population[57], which is equivalent to cancer risk in Barrett’s oesophagus[58]. Furthermore, oesophageal cancer diagnosis in achalasia patients is often delayed, contributing to a poor mean survival after diagnosis of only 0.7 years[53,59]. These findings would support the need for endoscopic surveillance in achalasia patients.

However, despite the relative risk being increased, the absolute risk of cancer in patients with achalasia is still small and there would be a large number of examinations required to detect a single cancer. In fact it has been estimated that for the detection of a single cancer there would need to be 681 endoscopic examinations undertaken[53]. Despite the potential complications associated with diagnosis, treatments and increased cancer risk, achalasia patients don’t experience a significant compromise to overall life expectancy[29]. The most recent guidelines indicate that surveillance endoscopy is not indicated[60].

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, achalasia remains a relatively under-researched condition with many details on aetiology, true incidence, and risk of complications still unknown. There has been some progress over the past years into the aetiology of the condition but there is a need for further research to be carried out into this field to establish causative agents. Furthermore, clarification in relation to the need for an endoscopic screening program in patients with achalasia to detect the development of oesophageal cancer is required.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers Bustamante-Balen M, Paulssen EJ S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor A E- Editor Li JY

References

- 1.Cotran RS, Kumar V, Collins T. Robbins Pathologic basis of disease. 6th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1999. pp. 778–779. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar P, Clark M. Clinical Medicine. 4th ed. Edinburgh: WB Saunders; 1998. pp. 229–231. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pohl D, Tutuian R. Achalasia: an overview of diagnosis and treatment. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2007;16:297–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, Kahrilas PJ, Pandolfino JE, Schwizer W, Smout AJ. Chicago classification criteria of esophageal motility disorders defined in high resolution esophageal pressure topography. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;24 Suppl 1:57–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01834.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pandolfino JE, Kwiatek MA, Nealis T, Bulsiewicz W, Post J, Kahrilas PJ. Achalasia: a new clinically relevant classification by high-resolution manometry. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1526–1533. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rohof WO, Hirsch DP, Kessing BF, Boeckxstaens GE. Efficacy of treatment for patients with achalasia depends on the distensibility of the esophagogastric junction. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:328–335. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pandolfino JE, de Ruigh A, Nicodème F, Xiao Y, Boris L, Kahrilas PJ. Distensibility of the esophagogastric junction assessed with the functional lumen imaging probe (FLIP™) in achalasia patients. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25:496–501. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boeckxstaens GE. Achalasia: virus-induced euthanasia of neurons. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1610–1612. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01967.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gockel I, Müller M, Schumacher J. Achalasia--a disease of unknown cause that is often diagnosed too late. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109:209–214. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2012.0209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park W, Vaezi MF. Etiology and pathogenesis of achalasia: the current understanding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1404–1414. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Francis DL, Katzka DA. Achalasia: update on the disease and its treatment. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:369–374. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howard PJ, Maher L, Pryde A, Cameron EW, Heading RC. Five year prospective study of the incidence, clinical features, and diagnosis of achalasia in Edinburgh. Gut. 1992;33:1011–1015. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.8.1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Birgisson S, Richter JE. Achalasia in Iceland, 1952-2002: an epidemiologic study. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:1855–1860. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9286-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sadowski DC, Ackah F, Jiang B, Svenson LW. Achalasia: incidence, prevalence and survival. A population-based study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:e256–e261. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mayberry JF, Atkinson M. Variations in the prevalence of achalasia in Great Britain and Ireland: an epidemiological study based on hospital admissions. Q J Med. 1987;62:67–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mayberry JF, Rhodes J. Achalasia in the city of Cardiff from 1926 to 1977. Digestion. 1980;20:248–252. doi: 10.1159/000198446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mayberry JF, Atkinson M. Studies of incidence and prevalence of achalasia in the Nottingham area. Q J Med. 1985;56:451–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arber N, Grossman A, Lurie B, Hoffman M, Rubinstein A, Lilos P, Rozen P, Gilat T. Epidemiology of achalasia in central Israel. Rarity of esophageal cancer. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1920–1925. doi: 10.1007/BF01296119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Earlam RJ, Ellis FH, Nobrega FT. Achalasia of the esophagus in a small urban community. Mayo Clin Proc. 1969;44:478–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galen EA, Switz DM, Zfass AM. Achalasia: incidence and treatment in Virginia. Va Med. 1982;109:183–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mayberry JF, Atkinson M. Incidence of achalasia in New Zealand, 1980-1984. An epidemiological study based on hospital discharges. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1988;3:247–257. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stein CM, Gelfand M, Taylor HG. Achalasia in Zimbabwean blacks. S Afr Med J. 1985;67:261–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farrukh A, DeCaestecker J, Mayberry JF. An epidemiological study of achalasia among the South Asian population of Leicester, 1986-2005. Dysphagia. 2008;23:161–164. doi: 10.1007/s00455-007-9116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ho KY, Tay HH, Kang JY. A prospective study of the clinical features, manometric findings, incidence and prevalence of achalasia in Singapore. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;14:791–795. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.1999.01950.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gennaro N, Portale G, Gallo C, Rocchietto S, Caruso V, Costantini M, Salvador R, Ruol A, Zaninotto G. Esophageal achalasia in the Veneto region: epidemiology and treatment. Epidemiology and treatment of achalasia. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:423–428. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1392-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Podas T, Eaden J, Mayberry M, Mayberry J. Achalasia: a critical review of epidemiological studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:2345–2347. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zendehdel K, Nyrén O, Edberg A, Ye W. Risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma in achalasia patients, a retrospective cohort study in Sweden. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:57–61. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ng KY, Li KF, Lok KH, Lai L, Ng CH, Li KK, Szeto ML. Ten-year review of epidemiology, clinical features, and treatment outcome of achalasia in a regional hospital in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J. 2010;16:362–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eckardt VF, Hoischen T, Bernhard G. Life expectancy, complications, and causes of death in patients with achalasia: results of a 33-year follow-up investigation. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:956–960. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282fbf5e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Booy JD, Takata J, Tomlinson G, Urbach DR. The prevalence of autoimmune disease in patients with esophageal achalasia. Dis Esophagus. 2012;25:209–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2011.01249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kraichely RE, Farrugia G, Pittock SJ, Castell DO, Lennon VA. Neural autoantibody profile of primary achalasia. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:307–311. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0838-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ghoshal UC, Daschakraborty SB, Singh R. Pathogenesis of achalasia cardia. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:3050–3057. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i24.3050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aetiology of achalasia. Accessed 21 July 2012. Available from: http: //bestpractice.bmj.com/best-practice/monograph/872/basics/aetiology.html.

- 34.Lau KW, McCaughey C, Coyle PV, Murray LJ, Johnston BT. Enhanced reactivity of peripheral blood immune cells to HSV-1 in primary achalasia. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:806–813. doi: 10.3109/00365521003587804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Castagliuolo I, Brun P, Costantini M, Rizzetto C, Palù G, Costantino M, Baldan N, Zaninotto G. Esophageal achalasia: is the herpes simplex virus really innocent. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:24–30; discussion 30. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Birgisson S, Galinski MS, Goldblum JR, Rice TW, Richter JE. Achalasia is not associated with measles or known herpes and human papilloma viruses. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:300–306. doi: 10.1023/a:1018805600276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaar TK, Waldron R, Ashraf MS, Watson JB, O’Neill M, Kirwan WO. Familial infantile oesophageal achalasia. Arch Dis Child. 1991;66:1353–1354. doi: 10.1136/adc.66.11.1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mayberry JF, Atkinson M. A study of swallowing difficulties in first degree relatives of patients with achalasia. Thorax. 1985;40:391–393. doi: 10.1136/thx.40.5.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chuah SK, Hsu PI, Wu KL, Wu DC, Tai WC, Changchien CS. 2011 update on esophageal achalasia. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1573–1578. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i14.1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lake JM, Wong RK. Review article: the management of achalasia-a comparison of different treatment modalities. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:909–918. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kurian AA, Bhayani N, Sharata A, Reavis K, Dunst CM, Swanström LL. Partial anterior vs partial posterior fundoplication following transabdominal esophagocardiomyotomy for achalasia of the esophagus: meta-regression of objective postoperative gastroesophageal reflux and dysphagia. JAMA Surg. 2013;148:85–90. doi: 10.1001/jamasurgery.2013.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boeckxstaens GE, Annese V, des Varannes SB, Chaussade S, Costantini M, Cuttitta A, Elizalde JI, Fumagalli U, Gaudric M, Rohof WO, et al. Pneumatic dilation versus laparoscopic Heller’s myotomy for idiopathic achalasia. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1807–1816. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spechler SJ. Pneumatic dilation and laparoscopic Heller’s myotomy equally effective for achalasia. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1868–1870. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1100693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoogerwerf WA, Pasricha PJ. Pharmacologic therapy in treating achalasia. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2001;11:311–324, vii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Allescher HD, Storr M, Seige M, Gonzales-Donoso R, Ott R, Born P, Frimberger E, Weigert N, Stier A, Kurjak M, et al. Treatment of achalasia: botulinum toxin injection vs. pneumatic balloon dilation. A prospective study with long-term follow-Up. Endoscopy. 2001;33:1007–1017. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-18935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cai XB, Dai YM, Wan XJ, Zeng Y, Liu F, Wang D, Zhou H. Comparison between botulinum injection and removable covered self-expanding metal stents for the treatment of achalasia. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:1960–1966. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-2564-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Akritidis N, Gousis C, Dimos G, Paparounas K. Fever, cough, and bilateral lung infiltrates. Achalasia associated with aspiration pneumonia. Chest. 2003;123:608–612. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.2.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Orringer MB, Stirling MC. Esophageal resection for achalasia: indications and results. Ann Thorac Surg. 1989;47:340–345. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(89)90369-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eckardt AJ, Eckardt VF. Current clinical approach to achalasia. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3969–3975. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dunaway PM, Wong RK. Risk and surveillance intervals for squamous cell carcinoma in achalasia. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2001;11:425–434, ix. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Streitz JM, Ellis FH, Gibb SP, Heatley GM. Achalasia and squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus: analysis of 241 patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;59:1604–1609. doi: 10.1016/0003-4975(94)00997-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Leeuwenburgh I, Scholten P, Alderliesten J, Tilanus HW, Looman CW, Steijerberg EW, Kuipers EJ. Long-term esophageal cancer risk in patients with primary achalasia: a prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2144–2149. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sandler RS, Nyrén O, Ekbom A, Eisen GM, Yuen J, Josefsson S. The risk of esophageal cancer in patients with achalasia. A population-based study. JAMA. 1995;274:1359–1362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stein HJ, Siewert JR. Barrett’s esophagus: pathogenesis, epidemiology, functional abnormalities, malignant degeneration, and surgical management. Dysphagia. 1993;8:276–288. doi: 10.1007/BF01354551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Leeuwenburgh I, Scholten P, Caljé TJ, Vaessen RJ, Tilanus HW, Hansen BE, Kuipers EJ. Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma are common after treatment for achalasia. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:244–252. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2157-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.da Rocha JR, Ribeiro U, Sallum RA, Szachnowicz S, Cecconello I. Barrett’s esophagus (BE) and carcinoma in the esophageal stump (ES) after esophagectomy with gastric pull-up in achalasia patients: a study based on 10 years follow-up. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:2903–2909. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0057-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brücher BL, Stein HJ, Bartels H, Feussner H, Siewert JR. Achalasia and esophageal cancer: incidence, prevalence, and prognosis. World J Surg. 2001;25:745–749. doi: 10.1007/s00268-001-0026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Coleman HG, Bhat S, Murray LJ, McManus D, Gavin AT, Johnston BT. Increasing incidence of Barrett’s oesophagus: a population-based study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2011;26:739–745. doi: 10.1007/s10654-011-9596-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zaninotto G, Rizzetto C, Zambon P, Guzzinati S, Finotti E, Costantini M. Long-term outcome and risk of oesophageal cancer after surgery for achalasia. Br J Surg. 2008;95:1488–1494. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Evans JA, Early DS, Fukami N, Ben-Menachem T, Chandrasekhara V, Chathadi KV, Decker GA, Fanelli RD, Fisher DA, Foley KQ, et al. The role of endoscopy in Barrett’s esophagus and other premalignant conditions of the esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;76:1087–1094. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]