Abstract

TRAF3IP2 is a cytoplasmic adapter protein and an upstream regulator of IKK/NF-κB and JNK/AP-1. Here we demonstrate for the first time that the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin (IL)-18 induces TRAF3IP2 expression in primary cardiac fibroblasts (CF) in a Nox4/hydrogen peroxide-dependent manner. Silencing TRAF3IP2 using a phosphorothioated, 2-O’-methyl modified, cholesterol-tagged TRAF3IP2 siRNA duplex markedly attenuated IL-18-induced NF-κB and AP-1 activation and CF migration. Using co-IP/IB and co-localization experiments, we show that Nox4 physically associates with IL-18 receptor proteins, and IL-18 enhances their binding. Further, IL-18 promotes fibroblast to myofibroblast transition, as evidenced by enhanced α-smooth muscle actin expression, types 1 and 3 collagen induction, and soluble collagen secretion, via TRAF3IP2. These results indicate that TRAF3IP2 is a critical intermediate in IL-18-induced CF migration and differentiation in vitro. TRAF3IP2 could serve as a potential therapeutic target in cardiac fibrosis and adverse remodeling in vivo.

Keywords: RNA interference, Cardiac fibroblasts, Migration, TRAF3IP2, Cardiac fibrosis, Remodeling

1. Introduction

Cardiac fibroblasts, the most abundant cell type in an adult mammalian heart, play a critical role in normal myocardial structure and function[1, 2]. Under normal physiological conditions, CF express various biomolecules, including low levels of cytokines, growth factors, matrix-degrading metalloproteinases (MMPs) and their regulators, and secrete collagens. Collagens contribute to the extensive extracellular matrix (ECM) in the heart that connect various cellular components[3]. ECM also serves as a reservoir for various secreted growth factors[3]. However, under pathological conditions, fibroblasts differentiate into myofibroblasts, express increased levels of proinflammatory molecules, growth factors, MMPs, and collagens[1–6].

Myofibroblasts are distinct from normal fibroblasts, and are usually detected in the heart after injury or chronic inflammation[1, 2, 6]. They are characterized by the increased expression of alpha smooth muscle actin (αSMA), smooth muscle myosin heavy chain, extra domain-A fibronectin, FGF-2, and TGFβ receptor II. While the principal role of myofibroblasts is to repair and resolve tissue injury, their persistent activation results in a maladaptive response, with adverse ECM remodeling and fibrosis. Interestingly, myofibroblasts can be detected in the fibrotic areas long after the injury or inflammation is resolved [4], contributing possibly to progression of the remodeling process.

The proinflammatory cytokine interleukin (IL)-18 induces cardiac fibroblast migration and proliferation [7], two critical processes involved in cardiac fibrosis and remodeling. IL-18 is a potent activator of NF-κB and AP-1 [8, 9], two redox-sensitive nuclear transcription factors known to positively regulate various proinflammatory cytokines and MMPs that contribute to cardiac injury, inflammation and remodeling. We previously demonstrated that IL-18 stimulates fibronectin expression and fibroblast migration via PI3K/Akt-dependent NF-κB activation [8]. The MAP kinase c-Jun N-terminal kinases/stress-activated protein kinase (JNK/SAPK) activates AP-1, and plays a role in IL-18-induced fibroblast migration and proliferation [7], indicating that both NF-κB and AP-1 are important mediators of the pro-migratory and/or pro-mitogenic effects of IL-18.

TRAF3 interacting protein 2 (TRAF3IP2; aka CIKS or Actl), is a redox-sensitive adapter molecule, and an upstream regulator of both IKK/NF-κB and JNK/AP-1 [10, 11]. We recently reported that angiotensin (Ang)-II upregulates TRAF3IP2 expression in vivo in heart and in vitro in isolated adult mouse cardiomyocytes [12]. While TRAF3IP2 gene deletion blunted Ang-II-induced myocardial hypertrophy, its knockdown by lentiviral shRNA attenuated Ang-II-induced cardiomyocyte growth in vitro. Further, Ang-II-induced TRAF3IP2 expression in cardiomyocytes in an IL-18-dependent manner [12]. We also demonstrated that TRAF3IP2 gene deletion blunts Ang-II-induced cardiac fibrosis [12]. However, expression of TRAF3IP2, its regulation and role in IL-18-induced cardiac fibroblast migration and differentiation were not investigated.

RNA interference is a physiological phenomenon, and regulates various cellular mechanisms, including cell survival and differentiation. Synthetic siRNA duplexes have been used successfully to inhibit target-specific gene expression. While 21-mer and 23-mer siRNA duplexes effectively down regulate their target gene expression, 27-mer siRNA duplexes (dicer substrate siRNA) have been shown to be much more potent in their knockdown effect as they have been shown to enter the RNAi pathway much earlier [13]. Therefore, we targeted TRAF3IP2 using 27-mer siRNA duplexes. Since phosphorothioation and 2-O’-methyl modifications enhance their stability, and cholesterol tagging increases their cellular uptake by several fold [13–15], we investigated the effect of phosphorothioated, 2-O’-methyl modified 3’-cholesterol tagged 27-mer siRNA duplex on IL-18-induced TRAF3IP2 expression, and CF migration and differentiation.

Here we report that compared to unmodified siRNA duplex, phosphorothioation and 2-O’-methyl modification were each relatively more effective in reducing TRAF3IP2 expression in mouse CF. However, cholesterol tagged phosphorothioated and 2-O’-methyl modified siRNA was much more effective in inhibiting IL-18 induced TRAF3IP2 expression, and CF migration and differentiation. These results demonstrate that TRAF3IP2 is a critical intermediate in IL-18-induced CF migration and differentiation in vitro, and suggest that targeting TRAF3IP2 by a modified siRNA has the potential to reduce cardiac fibrosis and adverse remodeling in vivo.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

DPI, BioCoat™ Matrigel™ invasion chambers, recombinant mouse IL-18, IL-18 neutralizing antibodies, IL-18 binding protein-Fc chimera (IL-18BP-Fc), and antibodies against TRAF3IP2, IL-18Rα, IL-18Rβ, Akt, p-p65, p65, p-cJun, JNK1, Tubulin, and GAPDH, were all previously described [8, 12]. TGFβ1 and pan-specific TGFβ polyclonal IgG were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Anti-Nox4 antibodies used in IP/IB were purchased from Epitomics (Cat. #: 3187-1; Burlingame, CA). Anti-Nox4 antibodies (#sc-21860) used in immunofluorescence were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). The NO donor DETA-NONOate was from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Monoclonal anti-αSMA antibody was from Sigma-Aldrich. Sodium pyruvate was from Invitrogen/Life Technologies (Grand Island, NY). The SAPK7JNK Kinase Assay Kit was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (#9810; Danvers, MA).

2.2. TRAF3IP2 27-mer siRNA and transfection

Three TRAF3IP2 (GenBank accession # NM_134000) Trilencer-27 siRNA duplexes and non-targeting control siRNA were purchased from Origene Technologies (Table 1). At first, we tested their silencing effect on basal and IL-18-induced TRAF3IP2 expression in CF. The most effective one was then modified to include phosphorothioation of two nucleotides on both ends in the sense strand, 2’O-methyl modification on both strands, and tagged with cholesterol at 3’-end as detailed in Table 1. Phosphorothioated, 2-O’-methyl modified cholesterol-tagged scrambled siRNA served as a control. siRNA duplexes were mixed with SiLentFect™ lipid reagent (Bio-Rad) to a final concentration of 10 nM, and transfected according to the manufacturer's instructions into CF at 50% confluency. After 36 h, cells were washed and used in the studies. At the indicated concentration and duration of treatment, the siRNA failed to modulate CF adherence, shape or viability (trypan blue-dye exclusion; data not shown).

Table 1.

Unmodified and modified TRAF3IP2 (NM_134000) 27-mer siRNA duplexes

| Unmodified siRNA | ||

|---|---|---|

| TRAF3IP2 | Sense (5’-3’) | Antisense (5’-3’) |

| siRNA#1 | CGAUCUUAGAAACUAGAAUGAACcg | CGGUUCAUUCUAGUUUCUAAGAUCGCC |

| siRNA#2 | GCCAGAAGAAUUACGGAAAGUCUtt | AAAGACUUUCCGUAAUUCUUCUGGCAA |

| siRNA#3 | GCAAUCCUAAUUGUAAACAGAGUaa | UUACUCUGUUUACAAUUAGGAUUGCUU |

| Modified siRNA | ||

| TRAF3IP2 | Sense (5’-3’) | Antisense (5’-3’) |

| M-siRNA#1 | mC*mG*AmUCmUUAGAAmACmUAmGAmAUGAAC*mc*g/3CholTEG/ | C*G*mGUUCAUmUCmUAmGUUUCUAAGAmUCmG*mC*mC |

| M-Scrambled | mC*mA*UmAUmUGCGCGmUAmUAmGUmCGCGUU*ma*g/3CholTEG/ | C*U*mAACGCGmACmUAmUACGCGCAAUmAUmG*mG*mU |

Phosphorothioated; m, 2-O’-methyl modified; 3CholTEG/, 3’-cholesterol-tagged, TEG, triethylene glycol used as a linker; Upper case letters, ribonucleotides; Lower case letters highlighted in blue, deoxyribonucleotides

2.3. Isolation of adult mouse cardiac fibroblasts (CF)

All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Care and Use Committees at the University of Texas Health Science Center in San Antonio and Tulane University in New Orleans, and conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the NIH. Fibroblasts were isolated from the hearts of 8–10-wk-old male wild type C57B1/6 and TRAF3IP2-null mice [16] as previously described [17]. Freshly isolated and up to second passage CF were used in all experiments. At 50–70% confiuency, the cells were made quiescent by incubating in medium containing 0.5% BSA (serum-free) for 48 h.

2.4. Adeno and lentiviral infection

Ad.siNox4 and Ad.siGFP were previously described [18]. Lentiviral p65 and cJun shRNA were from Sigma-Aldrich. CF were infected at ambient temperature with the viruses in PBS at the indicated multiplicity of infection (moi). After 1 h, the media containing adenovirus was replaced with culture media supplemented with 0.5% BSA. Assays were carried out after 48 h. The transfection efficiency with adenoviral vectors was near 100% as evidenced by the expression of GFP in CF infected with Ad.GFP (data not shown). For lentiviral infection, CF at 50–60% confiuency were infected with lentiviral particles at moi 0.5 in complete media for 48 hrs. At the indicated moi, adeno or lentiviral infection displayed no off-target effects and failed to affect cell viability and adherence (data not shown).

2.5. mRNA expression-RT-qPCR

Total RNA was isolated using the TRIzol method. One microgram of RNA was used for the first strand cDNA synthesis using Quantitect cDNA Synthesis Kit. Collagen mRNA expression was analyzed by RT-qPCR using TaqMan® probes (Collagen type lal, Mm00801666_gl; collagen type 3a 1, Mm01254476_ml) and Eppendorf Realplex4 system. Data are shown as fold change (2−ΔΔCt).

2.6. Detection of hydrogen peroxide by Amplex Red assay

Quiescent CF were treated with IL-18 (10 ng/ml for 30 min). H2O2 production was measured according to the manufacturer’s instructions using a commercially available kit (Amplex Red hydrogen peroxide/peroxidase assay kit, Molecular Probes Inc/Life Technologies) in the presence of horseradish peroxidase (0.1 unit/ml, Amplex Red: and 50 µM). Fluorescence was recorded at 530 nm excitation and 590 nm emission wavelengths (CytoFluor II; Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Standard curves were generated using known concentrations of H2O2. Studies were also performed after DPI or pyruvate pretreatment, or Ad.siNox4 transduction.

2.7. Immunoblotting and kinase assay

Preparation of whole cell homogenates, membrane extracts, immunoblotting, detection of the immunoreactive bands by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL Plus; GE Healthcare), and their quantification by densitometry were all previously described [12, 17–20]. JNK activity was analyzed using the non-radioactive SAPK/JNK Kinase Assay Kit [9].

2.8. Binding interaction of IL-18R heterodimer with Nox4 by reciprocal immunoprecipitation (IP)/immunoblotting (IB)

IP/IB experiments were carried out as previously described [12]. For IP, equal amounts of membrane extracts or whole cell lysates were incubated overnight at 4 °C with specific antibodies attached to agarose beads under slow rotation. After washing three times in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris.HCl, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Nonidet P-40, the bound proteins were eluted from the beads by boiling in SDS sample buffer for subsequent SDS-PAGE and IB.

2.9. Co-localization of IL-18R and Nox4 by immunofluorescence

The physical association of IL-18R and Nox4 resulting in their co-localization was analyzed by double immunofluorescence. In brief, CF at 70–80% confluence, were made quiescent by incubating in medium supplemented with 0.5% BSA for 48h. The quiescent CF were then treated or not with IL-18 (10 ng/ml) for 10 min, trypsinized, washed in cold PBS, and cytospun onto coated microscope slides. The cells were fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min at room temperature (RT; ~22°C), permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 2 min and blocked with 5% non-immune serum in PBST (PBS+ 0.1% Tween 20) for 30 min at RT. CF were then incubated with a mixture of Nox4 and IL-18Rα or IL-18Rβ antibodies described under IP/IB, for 1 h at RT, and 14 h at 4°C. After washing in PBST for three times, the CF were incubated with a mixture of secondary antibodies (FITC-conjugated anti-goat IgG and Rhodamine-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG, washed, and mounted in Vectashield. Cells were visualized using fluorescent microscopy (Zeiss Axio Imager Ml). Images were acquired at the same exposure time and magnification for comparison.

2.10. Sircol collagen assay

The effect of IL-18 on soluble collagen secretion was determined as previously described [21] using the Sircol collagen assay, which is based on the specific binding of the anionic dye Sirus red to the basic amino acid residues of collagen. Cell numbers were quantified by CyQuant assay as previously described [22], and collagen levels were normalized to cell numbers, and expressed as fold change from untreated.

2.11. Immunofluorescence

αSMA expression was analyzed by immunofluorescence. In brief, after transfection for 48 with the indicated siRNA, cells were plated in chamber slides, fixed in 3.7% paraformaldehyde, permeabilised in 0.1% Triton X-100, blocked with 1% BSA, incubated with anti-αSMA antibody (1 h at 22°C, 16 h at 4°C), washed and incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 conjugated secondary antibody (green), followed by nuclear staining with 4’-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; blue). Cells were visualized using fluorescent microscopy (Zeiss Axio Imager Ml). Images were acquired at the same exposure time and magnification for comparison.

2.12. Cell migration

CF migration was quantified as described previously using BioCoat™ Matrigel™ invasion chambers and 8.0-µm pore polyethylene terephthalate membranes with a thin layer of Matrigel™ basement membrane matrix [17]. Cultured CF were trypsinized and suspended in RPMI + 0.5% bovine serum albumin, and 1 ml containing 2.0 × 105 cells/ml was layered on the coated insert filters. Cells were stimulated with IL-18 (10 ng/ml). The lower chamber contained similar levels of IL-18. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 12 h. Membranes were washed with PBS, and non-invading cells on the upper surface were removed using cotton swabs. CF invading into and through the Matrigel™ matrix was quantified by MTT assay [17]. Results of IL-18 effects on CF migration were normalized with the migration of untreated cells and expressed as fold change from untreated.

2.13. Statistical analysis

Comparisons between controls and various treatments were performed by analysis of variance with post hoc Dunnett's t tests. All assays were performed at least three times, and the error bars in the figures indicate the S.E. Densitometric results were shown as ratios and fold changes from untreated at the bottom of the panels whenever the results are less clear.

3. Results

3.1. TRAF3IP2 mediates IL-18-induced cardiac fibroblast migration

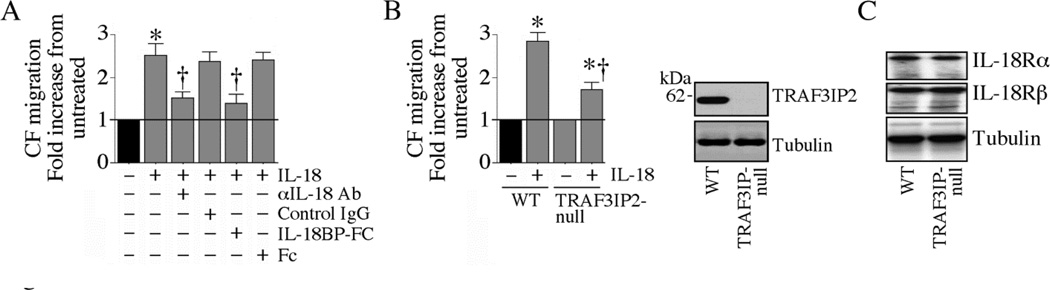

Treatment of adult mouse cardiac fibroblasts (CF) with IL-18, but not neutralized IL-18, stimulated significant cell migration (Fig. 1A). Preincubation with IL-18BP, a natural IL-18 antagonist, similarly attenuated IL-18-induced CF migration (Fig. 1A). Compared to wild type cells, CF isolated from TRAF3IP2-null mice showed a marked impairment in IL-18-induced migration (Fig. 1B). This reduced responsiveness is not due to IL-18 receptor downregulation (Fig. 1B, right panel). These results indicate that TRAF3IP2 plays a role in IL-18-induced CF migration (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. IL-18 induces cardiac fibroblast (CF) migration via TRAF3IP2.

A, IL-18 induces CF migration. At 70–80% confluence, CF were made quiescent by incubating in medium supplemented with 0.5% BSA for 48h. The quiescent CF were trypsinized, re-suspended in medium containing 0.5% BSA, layered on Matrigel™ basement membrane matrix-coated filters, and then treated with recombinant mouse IL-18 (10 ng/ml for 12 h). The lower chamber contained similar levels of IL-18. Specificity of IL-18 was verified by incubating the cells with IL-18A-neutralizing antibodies or IL-18BP-Fc (10 µg/ml) for 1 h prior to IL-18 addition. Cells migrating to the other side of the membrane were quantified using MTT assay. *P < 0.001 vs. untreated; †P< 0.01 vs. IL-17A (n=6). B, TRAF3IP2 gene deletion blunts IL-18-induced CF migration. CF isolated from WT and TRAF3IP2-null mice were made quiescent, and analyzed for IL-18-induced migration as in A. Lack of TRAF3IP2 expression was confirmed by immunoblotting (inset). *P< at least 0.01 vs. respective untreated; †P< 0.05 vs. WT-IL-18; (n=6). C, TRAF3IP2 gene deletion does not modify basal IL-18R subunit expression. CF isolated from TRAF3IP2-null mice or WT controls were made quiescent, and analyzed for IL-18Rα and IL-18Rβ expression by immunoblotting using cleared whole cell homogenates (n=3).

3.2. IL-18 induces TRAF3IP2 expression via Nox4 activity

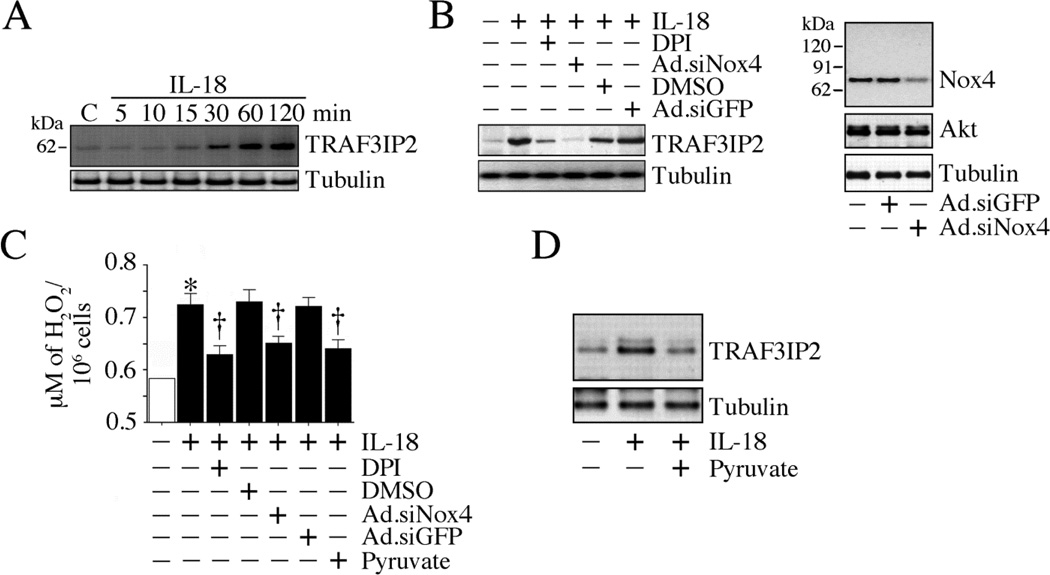

Since TRAF3IP2 gene deletion blunts IL-18-induced CF migration (Fig. 1), we next investigated whether IL-18 induces TRAF3IP2 expression in CF. Indeed, IL-18 upregulated TRAF3IP2 expression in a time-dependent manner, with increased levels detected only after 30 min (Fig. 2A). Its levels peaked at 2 h (Fig. 2A). Since TRAF3IP2 is a redox-sensitive adapter protein, we next investigated whether reactive oxygen species (ROS) are involved in its induction. Among the various sources of ROS in the cell, the NADPH oxidases have been shown to mediate a number of ligand/receptor signaling pathways. Among various NADPH oxidase proteins, Nox4 is the isoform predominantly expressed in CF [22] and H2O2 is the measurable product of its activation [23]. Knockdown of Nox4 using adenovirus shRNA inhibited IL-18-induced TRAF3IP2 expression, as did the flavoprotein inhibitor DPI (Fig. 2B). Further, both DPI and Nox4 knockdown inhibited IL-18-induced H2O2 production (Fig. 2C). Treatment with the hydrogen peroxide scavenger pyruvate similarly inhibited IL-18-induced H2O2 production (Fig. 2C) and TRAF3IP2 induction (Fig. 2D). These results demonstrate that IL-18 induces TRAF3IP2 expression in CF via Nox4/H2O2-dependent signaling (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. IL-18 induces TRAF3IP2 expression via Nox4 and H2O2.

A, IL-18 induces TRAF3IP2 expression. The quiescent CF treated with IL-18 (10 ng/ml) were analyzed for TRAF3IP2 expression by immunoblotting (n=3). B, IL-18 induces TRAF3IP2 expression via Nox4. CF were transduced with Ad.siNox4 (moi 100 for 48 h), made quiescent, and then treated with IL-18 (10 ng/ml for 2 h). Studies were also performed after DPI pre-treatment (10 µg/ml for 30 min). Knockdown of Nox4 was confirmed by immunoblotting (right side). Akt served as an off-target. TRAF3IP2 expression was analyzed by immunoblotting as in A (n=3). C, IL-18 stimulates Nox4-dependent H2O2 generation. CF infected with Ad.siNox4 (moi 100 for 48 h) or treated with DPI (10 µg/ml for 30 min) prior to IL-18 addition (10 ng/ml) were analyzed for H2O2 production using the Amplex Red assay. *P< 0.01 vs. untreated; †P< at least 0.05 vs. IL-18 (n=6). D, The H2O2 scavenger sodium pyruvate inhibits IL-18-induced H2O2 production and TRAF3IP2 induction. CF treated as in C, but with sodium pyruvate (10 mM for 1 h) prior to IL-18 addition (10 ng/ml) were analyzed for H2O2 production by Amplex Red assay (C; n=6) and TRAF3IP2 expression by immunoblotting (D; n=3).

3.3. IL-18R physically associates with Nox4

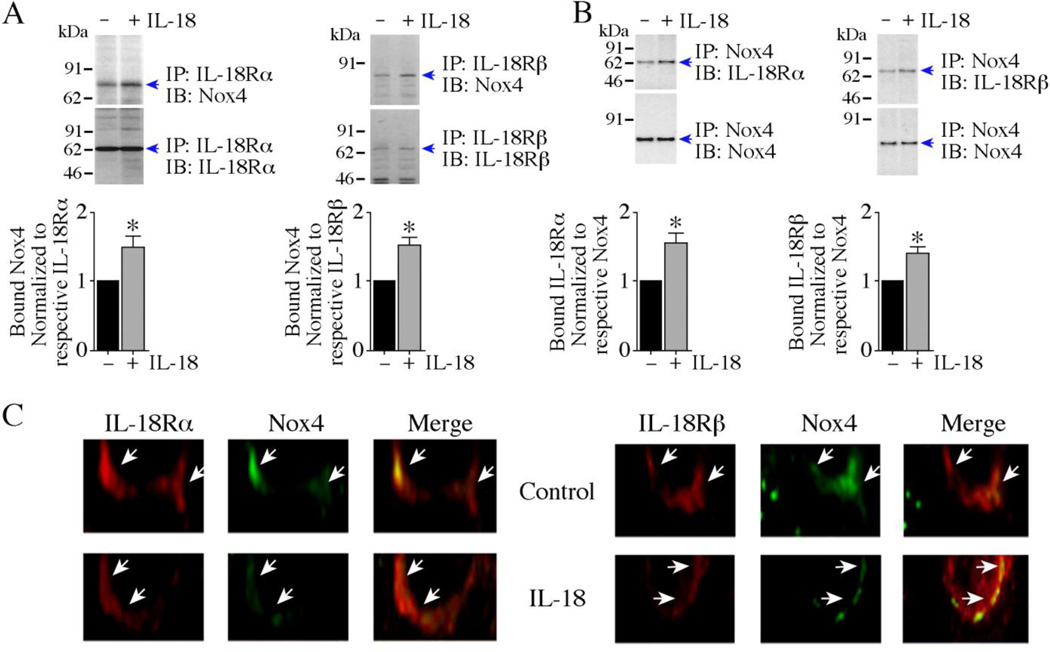

IL-18 signals via the IL-18 receptor, a heterodimer comprised of a ligand binding α subunit and a signal transducing β subunit. We previously reported that IL-18R physically associates with Noxl in smooth muscle cells, and IL-18 enhanced their binding [20]. Therefore, we investigated whether IL-18R also binds Nox4. We carried out reciprocal IP/IB of solubilized membrane preparations and whole cell lysates from CF treated with IL-18 for 10 min. As shown in Fig. 3, antibodies to both subunits of IL-18R co-immunoprecipitated Nox4 in the unstimulated cells, and stimulation with IL-18 enhanced their physical association (Fig. 3A, left and right panels; indicated by arrows). These results were confirmed when Nox4 immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted with antibodies against IL-18Rα and IL-18Rβ (Fig. 3B, left and right panels).

Fig. 3. IL-18 enhances IL-18R/Nox4 physical association.

A, B, IL-18 increases IL-18R/Nox4 physical association. Quiescent CF were treated with IL-18 (10 ng/ml) for 10 min. IL-18Rα and IL-18Rβ were immunoprecipitated and their binding to Nox4 was analyzed by IP/IB using solubilized membrane fraction (A, left and right panels). In a reciprocal IP/IB, binding of Nox4 immunoprecipitates to IL-18R heterodimer were analyzed using solubilized membrane fraction (B, left and right panels). The specific bands indentified by immunoblotting are indicated by arrows on the right. Molecular weight markers are shown on the left. The intensity of bands indicated by arrows is semiquantified by densitometric analysis, and results from three independent experiments are summarized in the respective lower panels. A, B, *P< 0.05. C, Co-localization studies for IL-18R and Nox4 in CF. Quiescent CF were treated or not with IL-18 (10 ng/ml) for 10 min. Endogenous IL-18R and Nox4 detected by immunofluorescence using anti-IL-18Rα or anti-IL-18Rβ, and anti-Nox4 antibodies described in ‘Material and methods’, and visualized using rhodamine and FITC-labeled secondary antibodies, respectively. Arrows indicate localization of IL-18R and Nox4 at the plasma membrane (400X).

We next determined the physical association of Nox4 with IL-18R in colocalization experiments using double immunofluorescence staining of CF treated or not with IL-18. As shown in Fig. 3C, IL-18Rα and Nox4 (left panels) and IL-18Rβ and Nox4 (right panel) were found co-localized at the plasma membrane at low levels at basal conditions, and their association was increased following IL-18 treatment (lower panels). No specific signals were detected when control IgG of respective species were used in place of primary antibody (data not shown). These results confirm the IP/IB results shown in Fig. 3A and 3B, and indicate a physical association between IL-18R and Nox4 at basal condition, and enhanced by IL-18 (Fig. 3).

3.4. Phosphorothioated, 2-O’-methyl modified, cholesterol-tagged TRAF3IP2 27-mer siRNA duplex markedly attenuates IL-18-induced TRAF3IP2 expression and CF migration

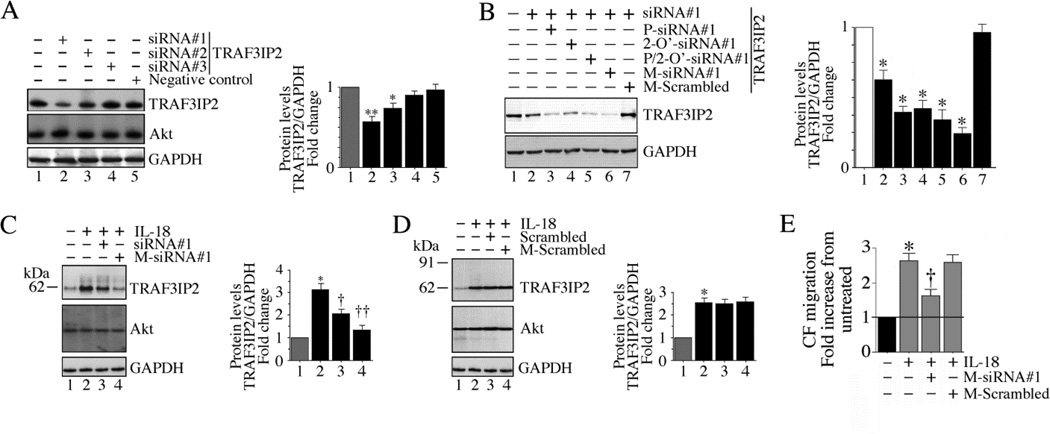

TRAF3IP2 gene deletion attenuates IL-18-induced CF migration (Fig. 1B). However, to date, there are no specific pharmacological inhibitors available that can inhibit TRAF3IP2 expression and function. Therefore, we targeted TRAF3IP2 expression by a 27-mer siRNA duplex. At first, we tested three different commercially available 27-mer duplexes (Table 1) on basal TRAF3IP2 expression. CF were transiently transfected with each of the three siRNA. Non-targeting 27-mer siRNA duplex served as a control. Among the three, siRNA#1 markedly inhibited basal TRAF3IP2 expression, whereas siRNA#2 had only moderate inhibitory activity, and siRNA#3 had no effect (Fig 4A). We then modified siRNA#1 to include either (i) phosphorothioation, or (ii) 2-O’-methyl modification or (iii) phosphorothioation+ 2-O’-methyl modification + cholesterol-tagging. Results in Fig. 4B show that while show that while phosphorothioated and 2-O’-methyl modified siRNA reduced basal TRAF3IP2 in the CF to a similar extent, the phosphorothioated, 2-O’-methyl modified, cholesterol-tagged siRNA (modified siRNA#1 or M-siRNA#1) was much more effective. We then investigated its efficacy in reducing IL-18-induced upregulation of TRAF3IP2 expression. Compared to the unmodified parent siRNA, M-siRNA#1 was more effective in attenuating IL-18-induced TRAF3IP2 expression (Fig. 4C). However, neither unmodified nor modified scrambled siRNA modulated inducible TRAF3IP2 expression (Fig. 4D). The reduction is TRAF3IP2 expression was not due to cell death as all siRNA, at the indicated concentrations and duration of treatment, failed to modulate cell viability (data not shown). Importantly, the modified-siRNA#1 markedly attenuated IL-18-induced CF migration (Fig. 4E). These results demonstrate that phosphorothioated, 2-O’-methyl modified, cholesterol-tagged 27-mer siRNA can efficiently knockdown basal as well as IL-18-induced TRAF3IP2 expression and CF migration (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Modified 27-mer TRAF3IP2 siRNA inhibits IL-18-induced TRAF3IP2 expression.

A, Unmodified 27-mer TRAF3IP2 siRNA inhibits basal TRAF3IP2 expression. CF were transfected with one of three siRNA duplexes (10 nM) using 0.5 µl siLentFect™ Lipid reagent. After 36 h, TRAF3IP2 expression was analyzed by immunblotting using cleared whole cell lysates. Non-targeting siRNA served as a control. Akt served as an off-target. GAPDH served as an internal control. B, Effect of various siRNA modifications on TRAF3IP2 knockdown. siRNA#1 was phosphorothioated (P-siRNA#1), 2-O’-methyl modified (2-O’-siRNA#1) or phosphorothioated, 2-O’-methyl modified, and cholesterol-tagged (M-siRNA#1). Phosphorothioated, 2-O’-methyl modified, and cholesterol-tagged scrambled siRNA (M-Scrambled) served as a control. CF were transfected and analyzed for TRAF3IP2 expression as in A. Densitometric results from three independent experiments are summarized on the right. *P < 0.05, **P< 0.01 vs. M-Scrambled. C, Modified TRAF3IP2 siRNA inhibits inducible TRAF3IP2 expression. CF transfected with M-siRNA#1 for 36 h were treated with IL-18 (10 ng/ml for 2 h). TRAF3IP2 expression was analyzed as in A. Densitometric results from three independent experiments are summarized on the right. *P< 0.05, **P< 0.01 vs. M-Scrambled. D, Scrambled siRNA fail to modulate inducible TRAF3IP2 expression. CF transfected with unmodified or modified scrambled TRAF3IP2 siRNA for 36 h were treated with IL-18 (10 ng/ml for 2 h). TRAF3IP2 expression was analyzed as in A. Densitometric results from three independent experiments are summarized on the right. *P< 0.01 vs. IL-18 (n=3). E, Modified TRAF3IP2 siRNA markedly attenuates IL-18-induced CF migration. CF transfected with the modified or scrambled TRAF3IP2 siRNA for 36 h were incubated with IL-18 (10 ng/ml for 12 h). Cell migration was analyzed as in Fig. 1A. *P< 0.001 vs. untreated, †P< 0.01 vs. IL-18+M-scrambled (n=6).

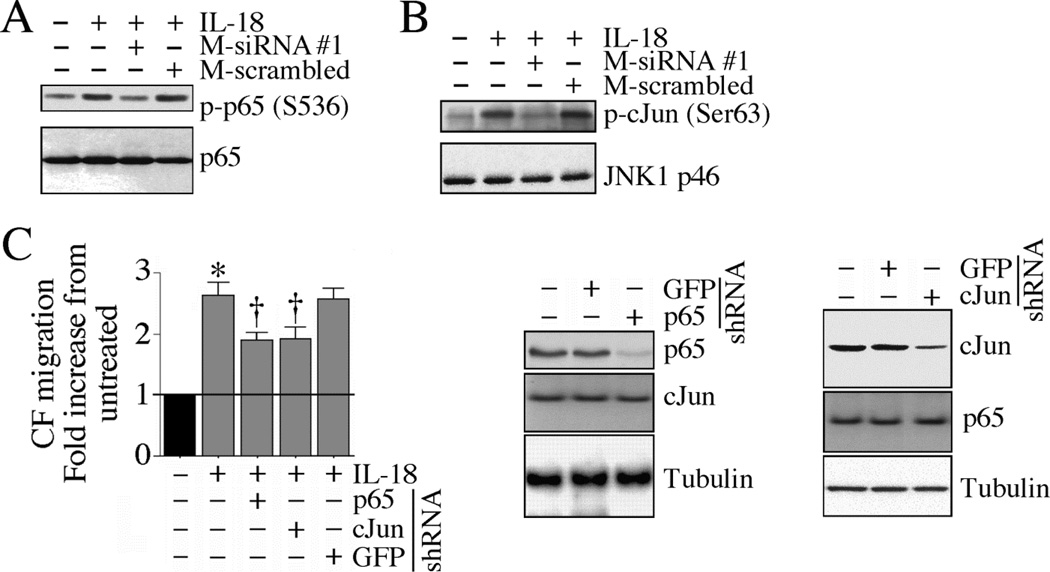

3.5. IL-18 induces CF migration via TRAF3IP2-dependent NF-κB and AP-1 activation

Since TRAF3IP2 is an upstream regulator of both IKK/NF-κB and JNK/AP-1 [10, 11] and both NF-κB and AP-1 pathways have been implicated in IL-18-induced cell migration, we next investigated whether targeting TRAF3IP2 will blunt NF-κB and AP-1 activation, and CF migration. IL-18-induced p65 phosphorylation (Fig. 5A) and JNK activation (Fig. 5B) were markedly attenuated by the modified-siRNA#1. Further, knockdown of p65 and cJun inhibited IL-18-induced CF migration (Fig. 5C). These results demonstrate that TRAF3IP2 mediates IL-18-induced NF-κB and AP-1 activation and CF migration (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5. IL-18 induces CF migration via TRAF3IP2-dependent NF-κB and AP-1 activation.

A, B, TRAF3IP2 mediates IL-18-induced p65 and JNK activation. CF transfected with the modified TRAF3IP2-specific siRNA for 36 h were incubated with IL-18 (10 ng/ml for 1 h) and then analyzed for p65 (A) and JNK (B) activation by immunoblotting using activation-specific antibodies (A) or in vitro kinase assay (B) (n=3). C, p65 and cJun knockdown attenuates IL-18-induced CF migration. CF transduced with lentiviral p65 or cJun shRNA (moi 0.5 for 48 h) were analyzed for IL-18-induced CF migration as in Fig. 1A. Knockdown of p65 and cJun was confirmed by immunoblotting as shown on the right. *P< 0.001 vs. untreated, †P< 0.05 vs. IL-18±GFP (n=6).

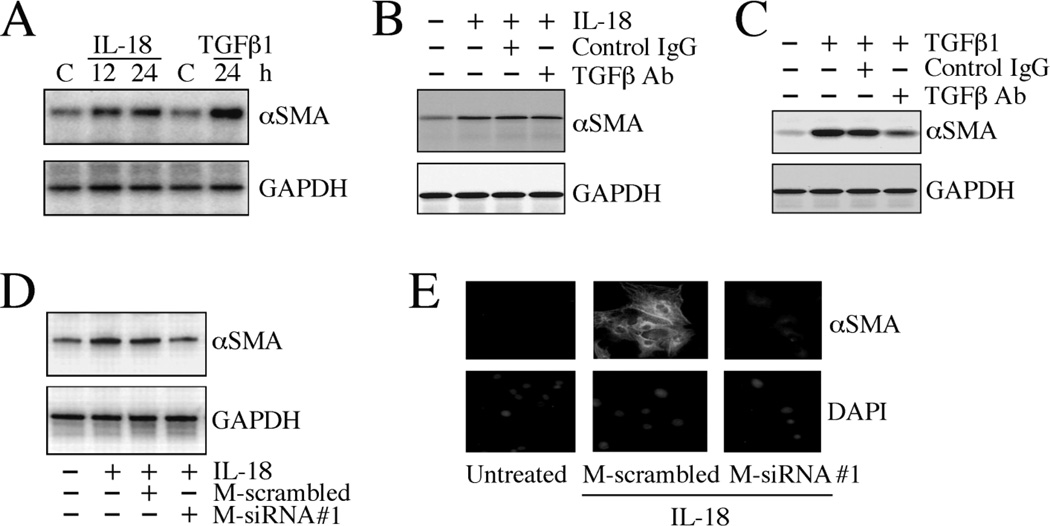

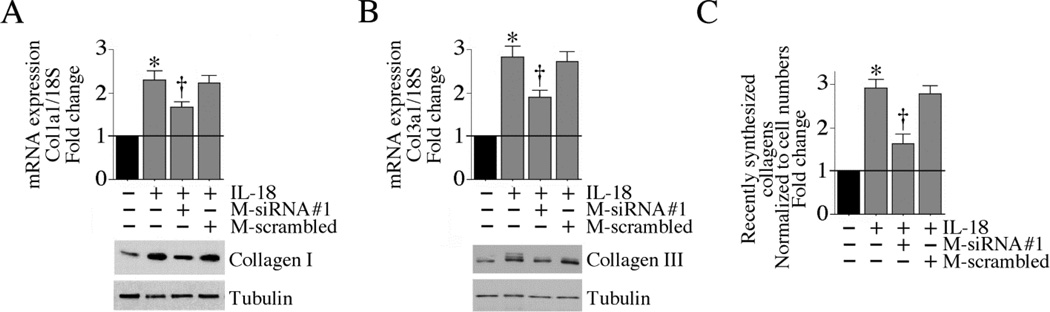

3.6. TRAF3IP2 mediates IL-18-induced cardiac fibroblast differentiation

Following injury and chronic inflammation, cardiac fibroblasts differentiate into myofibroblasts, express cytokines and growth factors, secrete collagens, and regulate wound repair and resolution [1–3, 6]. This phenotypic change is characterized by increased αSMA expression and enhanced collagen expression. Therefore, we investigated whether TRAF3IP2 contributes to IL-18-induced CF differentiation. Incubation with IL-18 increased αSMA expression in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 6A). TGFβ1 is known to positively regulate αSMA expression (Fig. 6A). However, pan-specific TGFβ neutralizing antibody failed to modulate IL-18-induced αSMA expression (Fig. 6B), but markedly attenuated that induced by TGFβ1 (Fig. 6C), demonstrating that the IL-18 induction of αSMA in CF is TGFβ1-independent. Importantly, modified-TRAF3IP2 siRNA markedly attenuated IL-18-induced αSMA expression (Fig. 6D), and immunofluorescence confirmed these results (Fig. 6E). Further, TRAF3IP2 knockdown attenuated collagens type lal (Fig. 7A) and type 3a1 (Fig. 7B) mRNA expression and protein levels (Figs. 7A, 7B, lower panels), and collagen secretion (Fig. 7C). These results indicate that in addition to mediating IL-18-induced CF migration, TRAF3IP2 also regulates the differentiation of this important cardiac cell type (Figs. 6 and 7).

Fig. 6. TRAF3IP2 knockdown inhibits CF differentiation.

A, IL-18 induces CF differentiation. The quiescent CF incubated with IL-18 (10 ng/ml) for the indicated time periods were analyzed for αSMA expression by immunoblotting. TGFβ1 (10 ng/ml for 24 h) served as a positive control (n=3). B, IL-18-induced CF differentiation is TGFβ1 independent. The quiescent CF were treated with pan-specific TGFβ neutralizing antibody (50 µg/ml for 1 h) prior to IL-18 addition (10 ng/ml for 24 h). αSMA expression was analyzed as in A (n=3). C, TGFβ neutralizing antibody inhibits TGFβ1 induced CF differentiation. The quiescent CF were treated with pan-specific TGFβ neutralizing antibody (50 µg/ml for 1 h) prior to TGFβ1 addition (10 ng/ml for 24 h). αSMA expression was analyzed as in A (n=3). D, IL-18-induced CF differentiation is TRAF3IP2-dependent. CF transfected with modified and unmodified TRAF3IP2 siRNA were made quiescent, incubated with IL-18 (10 ng/ml for 24 h), and analyzed for αSMA expression as in A (n=3). E, IL-18-induced TRAF3IP2-dependent CF differentiation was confirmed by immunofluorescent microscopy. CF treated as in B were analyzed for αSMA expression by immunofluorescence (green, upper panels). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue; lower panels). A representative of 3 independent experiments is shown (100X).

Fig. 7. TRAF3IP2 knockdown inhibits collagen expression and secretion.

A, B, Silencing TRAF3IP2 attenuates IL-18-induced collagen mRNA expression. CF transfected with modified and unmodified TRAF3IP2 siRNA were made quiescent, incubated with IL-18 (10 ng/ml for 2 h), and analyzed for collagens type 1a1 (A) and collagen type 3a1 (B) mRNA expression by RT-qPCR. Collagen I and III protein levels were analyzed by immunoblotting using cleared whole cell homogenates (respective lower panel; n=3). A, B, *P< 0.001 vs. untreated, †P< at least 0.05 vs. IL-18 (n=6). C, IL-18-stimulated collagen secretion is TRAF3IP2 dependent. CF treated as in A and B, but for 24 h with IL-18, were analyzed for recently synthesized collagens by Sircol collagen assay, normalized to cell numbers, and expressed as fold change from untreated. *P< 0.001 vs. untreated, †P< 0.01 vs. IL-18 (n=8).

4. Discussion

TRAF3IP2 is a cytoplasmic adapter protein and an upstream regulator of IKK/NF-κB and JNK/AP-1 [10, 11]. Various proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules, growth factors, and MMPs and their regulators that are induced during myocardial injury and inflammation are either NF-κB and/or AP-1-responsive, suggesting that TRAF3IP2 is a potentially important mediator of their induction and regulation, IL-18 is a pleiotropic proinflammatory cytokine, and a potent inducer of NF-κB and AP-1 activation [7–9], and interestingly, a NF-κB and AP-1 responsive gene. This suggests that once induced, IL-18 positively regulates its own expression and that of other NF-κB and AP-1 responsive genes, and can perpetuate the inflammatory response in part via TRAF3IP2.

Previously we reported that knockdown of TRAF3IP2 by a lentiviral shRNA markedly inhibits Ang-II-induced cardiomyocyte growth in vitro [12]. In vivo, TRAF3IP2 gene deletion reduced Ang-II-induced myocardial hypertrophy and fibrosis [12]. Further, TRAF3IP2 gene deletion or knockdown inhibited advanced oxidation protein product-induced cardiomyocyte death [19], indicating a role for TRAF3IP2 in cardiomyocyte growth and death. Both myocardial injury and chronic inflammation results in cardiomyocyte death, with surviving cardiomyocytes undergoing compensatory hypertrophy to maintain the pump function. On the other hand, following injury, fibroblasts differentiate into myofibroblasts, migrate, and proliferate, and secrete increased levels of various inflammatory mediators and extracellular matrix components, resulting in scar formation. Here we show for the first time that IL-18 induces TRAF3IP2 expression in CF, and its silencing inhibits IL-18-induced CF migration and differentiation in vitro.

TRAF3IP2 is a redox-sensitive adapter protein. IL-18 is a potent inducer of oxidative stress. Recently we reported a critical role for Nox1/superoxide in IL-18-induced TRAF3IP2 expression in SMC [20], and Nox2/superoxide-dependent TRAF3IP2 induction in Ang-II-treated cardiomyocytes [12], demonstrating an important role for NADPH oxidase-derived ROS generation in TRAF3IP2 induction. Among the various Nox isoforms, CF predominantly express Nox4 NADPH oxidase [22]. H2O2 is the only measurable product of its activation [23]. Here we show that Nox4 knockdown or pre-treatment with the flavoprotein inhibitor DPI each attenuate IL-18-induced H2O2 production and TRAF3IP2 induction. The H2O2 scavenger pyruvate similarly attenuated inducible TRAF3IP2 expression, implying a role for H2O2 in TRAF3IP2 induction. In fact, pathophysiological concentrations of H2O2 induce TRAF3IP2 expression in cardiomyocytes [19], demonstrating its redox nature. In fact, TRAF3IP2 promoter contains recognition sequences for several cis regulatory elements, including AP-1, C/EBP, and IRF-1 that are highly responsive to oxidative stress. We have previously reported that IL-18 activates these three transcription factors. It is therefore plausible that the rapid induction seen in TRAF3IP2 expression in IL-18-treated CF may be due to enhanced transcription. Of note, NOX4 is also a NF-κB-responsive gene [24]. This suggests that upon induction by IL-18, TRAF3IP2 activates both NF-κB and AP-1, and plays a role in further induction/activation of IL-18, Nox4, and TRAF3IP2, resulting in perpetuation of inflammatory stimuli. Targeting TRAF3IP2 could break this vicious cycle.

We also showed that siRNA-mediated TRAF3IP2 knockdown markedly inhibits IL-18-induced CF migration and differentiation. RNA interference is widely used to knockdown gene expression in a target-specific manner. Although 19, 21 and 23-mer siRNA can effectively silence their target genes, Amarzguioui, et al. reported that siRNA that are long enough to serve as Dicer substrates show greater potency in silencing their targets [14]. This is probably due to their entry early into the RNA-induced silencing complex. Therefore, we used a 25-mer siRNA duplex containing a 2-bp overhang (27-mer) to target basal as well as inducible TRAF3IP2 expression. Our results show that among the three siRNA duplexes tested, only one was highly effective in silencing basal TRAF3IP2 expression without off-target effects (Akt). Since site-specific chemical modifications such as phosphorothioation or 2-O’-methyl modifications increase siRNA stability [14], we modified TRAF3IP2 siRNA with each of these modifications, and further, tagged it with cholesterol to increase cellular uptake. Our results show that the phosphorothioated, 2-O’-methyl modified, cholesterol-tagged siRNA was particularly effective in silencing basal as well as inducible TRAF3IP2 expression, and IL-18-induced CF migration and differentiation.

Knockdown of TRAF3IP2 attenuated CF differentiation, as evidenced by the reduced levels of αSMA expression, collagens I and III induction, and collagens secretion. Here, αSMA expression served as a marker to denote differentiation of fibroblasts to myofibroblasts. TGFβ served as a positive control, and upregulated αSMA expression, and its neutralization by a pan-specific antibody attenuated its effects. However, TGFβ neutralizing antibodies failed to significantly modulate IL-18-induced αSMA expression. αSMA expression is regulated at both transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels. Its promoter region contains several response elements, including TGFβ control element (TCE) in its proximal promoter region that binds BTEB2, GKLF, Sp1, and Krüppel-like factors [25–27]. Its promoter region also contains SMAD-binding elements that are responsive to TGFβ [28]. Previously we reported that IL-18 activates Sp1 in cardiomyocytes [9]. Its effects on activation of other regulatory elements need investigation. Here, we found increased αSMA expression at 12 and 24 h after IL-18 addition. Similar to its effects on TRAF3IP2 induction, whether IL-18 stimulates αSMA expression at earlier time periods is not known. In future studies we will investigate the transcriptional regulation and temporal expression of αSMA in IL-18-treated CF to further characterize effects on CF differentiation.

Initially, IL-17 was the only cytokine thought to signal via TRAF3IP2 [29]. However here we show that IL-18 not only induces TRAF3IP2 expression, but also stimulates fibroblast migration and differentiation in part via TRAF3IP2. Several other inflammatory mediators that are known to contribute to cardiac fibrosis and adverse remodeling also induce TRAF3IP2 expression, including TNFα, IL-1 and LPS [30]. Chronic hypertension and diabetes, the traditional risk factors for coronary artery and cardiovascular diseases, and contributors to cardiac fibrosis, are characterized by inflammation and oxidative stress. We recently demonstrated that Ang-II, via IL-18, induces TRAF3IP2 expression in cardiomyocytes, and high glucose induces TRAF3IP2 expression in endothelial cells [12, 18]. These results suggest that enhanced TRAF3IP2 expression exerts pro-inflammatory, pro-survival, and pro-apoptotic effects, and targeting this pleiotropic adapter protein may inhibit IKK/NF-κB and JNK/AP-1 activation, and amplification in inflammatory signaling.

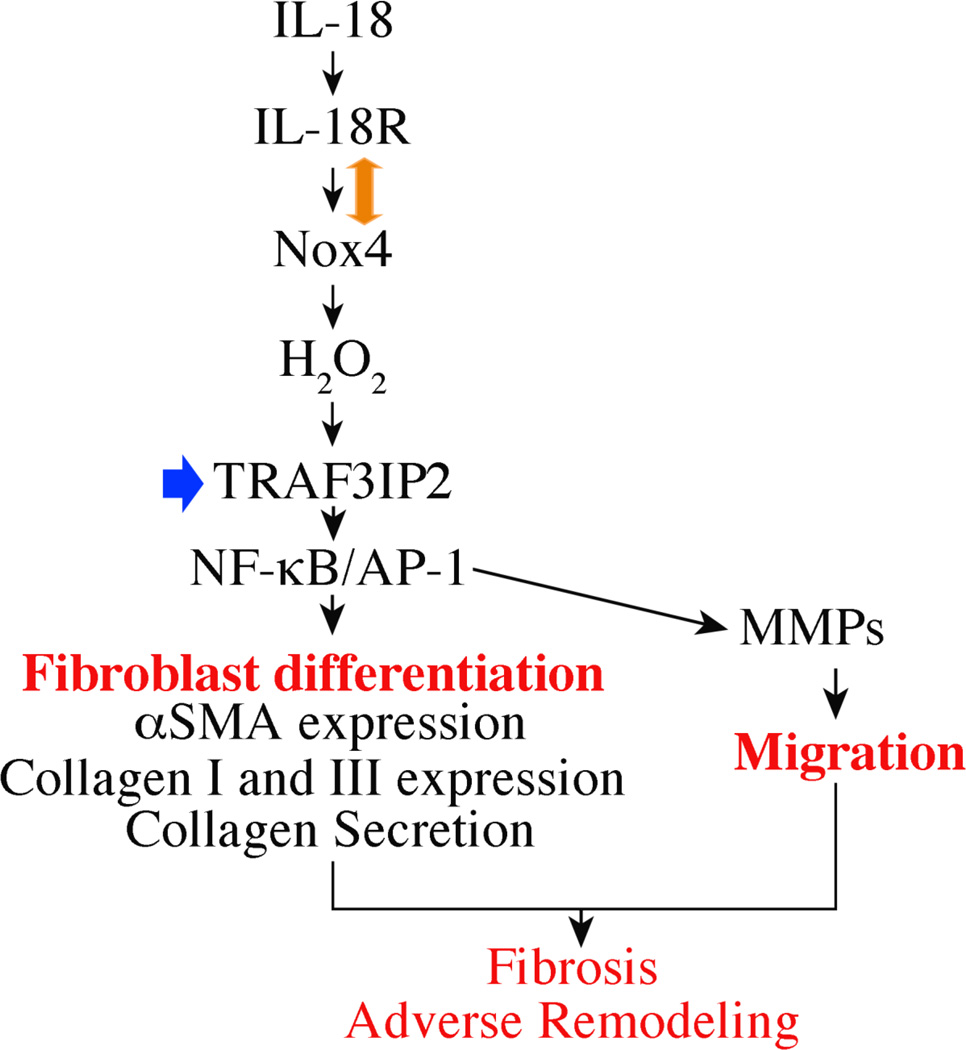

In summary, we demonstrated for the first time that targeting TRAF3IP2 by a modified 27-mer siRNA duplex inhibits IL-18-induced CF migration and differentiation in vitro. These results suggest that targeting TRAF3IP2 has the potential to blunt cardiac fibrosis and progression of adverse remodeling in vivo (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Schema showing IL-18-mediated TRAF3IP2-dependent cardiac fibroblast migration and differentiation in vitro. Targeting TRAF3IP2 (arrow in blue) has the potential to blunt cardiac fibrosis and progression of adverse remodeling in vivo. Double-headed arrow indicates protein-protein interactions.

Highlights.

Interleukin-18 induces cardiac fibroblast migration and differentiation in vitro

IL-18 induces TRAF3IP2 expression via Nox4/hydrogen peroxide

TRAF3IP2 knockdown inhibits fibroblast migration and differentiation

Targeting TRAF3IP2 may blunt myocardial fibrosis and adverse remodeling in vivo

Acknowledgements

BC is a recipient of the Department of Veterans Affairs Research Career Scientist award, and is supported by VA Office of Research and Development Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development Service Award 1IO1BX000246 and the NIH/NHLBI grant HL-86787. The contents of this report do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Abbreviations

- Ab

antibody

- Act1

activator of NF-κB

- Ang-II

angiotensin-II

- AP-1

activator protein-1

- BTEB2

Basic transcriptional element binding protein-2

- CF

cardiac fibroblasts

- CIKS

Connection to IKK and SAPK/JNK

- DAPI

4',6-Diamidino-2-Phenylindole, Dihydrochloride

- DETA-NONOate

Z)-1-[N-(2-aminoethyl)-N-(2-ammonioethyl)amino]diazen-1-ium-1,2-diolate

- DPI

diphenylene iodonium

- FGF

fibroblast growth factor

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- GKLF

gut-enriched Kruppel-like factor

- IκB

inhibitory κB

- IKK

IκB kinase

- IL

interleukin

- IP/IB

immunoprecipitation/immunoblotting

- IL-18R

Interleukin-18 receptor

- IRF-1

IFN regulatory factor-1

- JNK

c-Jun amino-terminal kinase

- moi

multiplicity of infection

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharide

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappa B

- Nox

NADPH oxidase

- NADPH

nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SAPK

stress-activated protein kinase

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- shRNA

small hairpin RNA

- αSMA

alpha smooth muscle actin

- SMAD

for SMA/MAD related

- SMC

Smooth muscle cells

- Sp1

Stimulatory protein 1

- TGF

transforming growth factor

- TRAF

TNF Receptor Associated Factor

- TRAF3IP2

TFAF3 interacting protein 2

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Chen W, Frangogiannis NG. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833(4):945–953. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.08.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Souders CA, Bowers SL, Baudino TA. Circ Res. 2009;105(12):1164–1176. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.209809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weber KT. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989;13(7):1637–1652. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90360-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Willems IE, Havenith MG, De Mey JG, Daemen MJ. Am J Pathol. 1994;145(4):868–875. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown RD, Ambler SK, Mitchell MD, Long CS. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2005;45:657–687. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kong P, Christia P, Frangogiannis NG. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1349-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fix C, Bingham K, Carver W. Cytokine. 2011;53(1):19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reddy VS, Harskamp RE, van Ginkel MW, Calhoon J, Baisden CE, Kim IS, Valente AJ, Chandrasekar B. J Cell Physiol. 2008;215(3):697–707. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reddy VS, Prabhu SD, Mummidi S, Valente AJ, Venkatesan B, Shanmugam P, Delafontaine P, Chandrasekar B. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;299(4):H1242–H1254. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00451.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leonardi A, Chariot A, Claudio E, Cunningham K, Siebenlist U. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(19):10494–10499. doi: 10.1073/pnas.190245697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li X, Commane M, Nie H, Hua X, Chatterjee-Kishore M, Wald D, Haag M, Stark GR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(19):10489–10493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160265197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valente AJ, Clark RA, Siddesha JM, Siebenlist U, Chandrasekar B. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;53(1):113–124. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim DH, Behlke MA, Rose SD, Chang MS, Choi S, Rossi JJ. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23(2):222–226. doi: 10.1038/nbt1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Amarzguioui M, Lundberg P, Cantin E, Hagstrom J, Behlke MA, Rossi JJ. Nat Protoc. 2006;1(2):508–517. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim DH, Rossi JJ. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8(3):173–184. doi: 10.1038/nrg2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Claudio E, Sonder SU, Saret S, Carvalho G, Ramalingam TR, Wynn TA, Chariot A, Garcia-Perganeda A, Leonardi A, Paun A, Chen A, Ren NY, Wang H, Siebenlist U. J Immunol. 2009;182(3):1617–1630. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.3.1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Valente AJ, Yoshida T, Gardner JD, Somanna N, Delafontaine P, Chandrasekar B. Cell Signal. 2012;24(2):560–568. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Venkatesan B, Valente AJ, Das NA, Carpenter AJ, Yoshida T, Delafontaine JL, Siebenlist U, Chandrasekar B. Cell Signal. 2013;25(1):359–371. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Valente AJ, Yoshida T, Clark RA, Delafontaine P, Siebenlist U, Chandrasekar B. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;60C:125–135. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valente AJ, Yoshida T, Izadpanah R, Delafontaine P, Siebenlist U, Chandrasekar B. Cell Signal. 2013;25(6):1447–1456. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Colston JT, de la Rosa SD, Koehler M, Gonzales K, Mestril R, Freeman GL, Bailey SR, Chandrasekar B. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;293(3):H1839–H1846. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00428.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colston JT, de la Rosa SD, Strader JR, Anderson MA, Freeman GL. FEBS Lett. 2005;579(11):2533–2540. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takac I, Schroder K, Zhang L, Lardy B, Anilkumar N, Lambeth JD, Shah AM, Morel F, Brandes RP. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(15):13304–13313. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.192138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu X, Murphy TC, Nanes MS, Hart CM. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2010;299(4):L559–L566. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00090.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adam PJ, Regan CP, Hautmann MB, Owens GK. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(48):37798–37806. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006323200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brembeck FH, Rustgi AK. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(36):28230–28239. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004013200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Black AR, Black JD, Azizkhan-Clifford J. J Cell Physiol. 2001;188(2):143–160. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu B, Wu Z, Phan SH. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;29(3 Pt 1):397–404. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0063OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gaffen SL. Curr Opin Immunol. 2011;23(5):613–619. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qian Y, Qin J, Cui G, Naramura M, Snow EC, Ware CF, Fairchild RL, Omori SA, Rickert RC, Scott M, Kotzin BL, Li X. Immunity. 2004;21(4):575–587. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]