Abstract

The factors that contribute to the development of B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL) are unknown, and the groups of individuals at the greatest risk for developing this common leukemia are not well defined. Molecular features are important for classifying cases of B-CLL, and it is now apparent that similarities among Ig rearrangements between patients may give important clues to the origin of this disease.

B-CLL classification depends on histological and molecular features

B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL) is the most common form of leukemia in Western countries and most frequently manifests with advancing age. It is characterized by a progressive accumulation of small, long-lived, mature lymphocytes in the blood, bone marrow, and lymphoid tissues as classified by the Revised European/American Lymphoma/WHO (REAL/WHO) classification system (1, 2). B-CLL can be staged according Binet (3) or Rai (4). Most B-CLL cells divide slowly and are distinctive in their CD19+CD5+CD23+ phenotype with low levels of surface membrane immunoglobulin (5). There are no clear genetic predispositions to the development of B-CLL or globally consistent chromosomal abnormalities among patients. Consequently, the etiology of the disease has thus far been elusive.

The Binet and Rai systems can be supplemented by recent findings that further subdivide cases of B-CLL. Cases in which Ig rearrangements are somatically hypermutated result in a milder clinical disease course and better overall survival, while cases in which the Ig sequences remain germline are more severe (6–9). Some cases of B-CLL have even been shown to carry out ongoing somatic hypermutation and class-switch recombination subsequent to activation-induced deaminase (AID) expression much as in germinal center cells (6, 10). An inverse correlation of Zap70 or CD38 expression has also been exploited for use in the clinical setting in order to distinguish B-CLLs of differing severity (11–13). Recent studies of gene expression and surface phenotype of B-CLL cells have revealed that most have a memory B cell phenotype (14, 15) regardless of mutation status. While it is possible that B-CLLs originate from an antigen-exposed memory B cell population, it is also conceivable that memory cell characteristics are acquired following transformation.

Common Ig rearrangements between patients are extremely unusual

While the etiology of B-CLL is yet unknown, an important study in this issue of the JCI by Ghiotto et al. (16), which complements previous reports (17, 18) (reviewed in refs. 19, 20), has yielded valuable insights into factors in the development of B-CLL. Ghiotto et al. report that 20% of a large panel of genetically unrelated IgG class-switched B-CLL cases contained identical Ig VJ and VDJ gene segments. For such a finding to occur by chance is extraordinarily remote. The Ig repertoire has the capacity to produce over 3.4 million functional rearrangements ([44VH × 27DH × 6JH] × [46Vκ × 5Jκ] or [36Vλ × 7Jλ]), yet our laboratory has never found a duplicate rearrangement between patients among a library of 10,000 sequences of normal tonsillar Ig transcripts. This suggests that a process of selection has enforced the use of the gene segment combination described by Ghiotto et al. While it is uncommon to find the particular gene segment combinations in patients with IgM+ B-CLL that the authors observed in patients with IgG+ B-CLL (VH4–39, DH6–13, and JH5), we have found that the VH4–39 gene segment has an increased representation in tonsils of aging adults (Kolar and Capra, unpublished observations). Fais et al. (17) found an increased use of unmutated VH1–69 rearrangements in patients with IgM+ B-CLLs that had a restricted set of DH and JH6 gene segments, but later these segments were not found to be increased in normal blood (21). While still unclear, it is possible that individual or tissue-specific gene segment distributions in aging individuals have a role in particular antigen interactions of B-CLL clones.

Clonotypic Igs are seen in other disease processes

Other immunological diseases that have similar widespread clonotypic Ig manifestations have also been shown to be associated with infection or antigen. One such example is essential mixed cryoglobulinemia (EMC), in which monoclonal IgM antibodies are reactive to polyclonal IgG at temperatures lower than 37°C. Long after EMC was discovered, it was found to be associated with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection (22, 23) and often makes use of the VH1–69 gene segment, as do responses to HCV (24). B-CLL is not associated with HCV infection (25), but the antigen-induced expansion of clonotypic B cells may be similar. Over twenty-five years ago, our laboratory showed that the similarity among heavy chain complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) 2 and 3 in the mixed cryoglobulin rheumatoid factors Pom and Lay (26, 27) was perhaps an early hint of similar results to those reported by Ghiotto et al. in this issue (16). EMC now is thought to arise from CD5– immunocytomas that are considered marginal zone lymphomas. It is noteworthy that one of the patients described by Ghiotto et al. was identified as an immunocytoma case. Indeed, monoclonal cryoglobulins are often associated with underlying B-CLL or other lymphoproliferative diseases. In the subset of IgG+ B-CLL sequences reported in the study by Ghiotto et al., the CDR3 amino acid sequences are nearly identical, lending the possibility that they arise as a result of similar mechanisms.

Foreign or autoantigens may play a role in B-CLL

It remains to be determined, however, in the case of B-CLL whether a foreign or autoantigen is involved and what role it plays in the progression of the disease (Figure 1). The similarity of Ig clones that have been encountered in the Ghiotto et al. study (16) may provide an important clue to the identification of the antigen. Using Ars as an immunogen, our laboratory showed many years ago that the same Ig rearrangements were used in response to this very small hapten in spite of being isolated from different (albeit genetically identical) mice (28–31). Such findings have been reported in other systems involving immunization with small haptens. In the arsonate system, the amino acid junction sequences of the rearrangements were identical, and an arginine residue at position 99 of the light chain VJ junction of anti-Ars antibodies was shown to be essential for the antibody to recognize this hapten (32). While certain gene segments have been commonly associated with B-CLL (indeed, this led to the discovery of the VH5 gene segment family, ref. 33), the primary structure of the B cell receptor in B-CLL, particularly IgG clones, appears to be more restricted than has previously been thought. There is ample evidence of highly restricted immune responses from the mouse myelomas to carbohydrates (34), raising the possibility that clonal populations in B-CLL patients may be specific for carbohydrate antigens. Marginal zone B cells appear to be important for polysaccharide responses (35–38) and may be involved in the development of B-CLL.

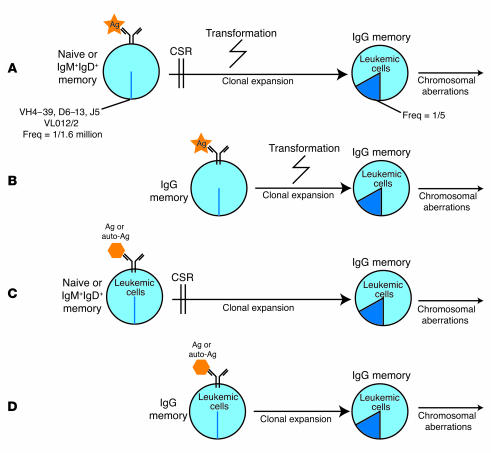

Figure 1.

Antigen may play a role in the progression of class-switched B-CLL in a number of ways: (A) a foreign agent is recognized by an unmutated B cell and aids in the transformation of the cell once it is internalized, or (B) an unmutated IgG memory cell may serve as a starting point prior to transformation. Alternatively (C or D) B-CLL cells with a particular rearrangement may recognize an autoantigen or foreign antigen and in response expand and undergo class-switch recombination. Freq, frequency; Ag, antigen; CSR, class switch recombination.

Ghiotto et al. (16) discuss features of the antigen-binding domain of the B-CLL clones that were visualized by homology modeling. The remarkable similarity among the entire rearrangement and heavy-light chain combinations also resembles those seen in several model systems in responses to small haptens. Of particular interest is a conserved arginine in the base of the binding pocket (which is the result of a recombination) much like that seen in anti-Ars responses in mice. A prominent bulge on the side of three of the five heavy-chain CDR3s was also evident and may provide an unusual surface for an antibody-antigen interaction.

Studies concerning the role and nature of antigens involved in the natural history of B-CLL will clearly have important clinical implications. B-CLLs appear to originate from existing cells, perhaps in the marginal zone, that have special cell phenotypes, producing antibodies against what is likely a very small ligand. Chronic antigenic stimulation of a defined subset of B cells may play an important role in the development of B-CLL pathogenesis. It is possible that individuals have different genetic predispositions, due to polymorphic variations in their immunoglobulin loci, to developing B-CLL clonal expansions in response to certain antigens. Targeted vaccination or methods to maintain tolerance for particular autoantigens may play an important future role in preventative therapies. More practically, the presence of frequent types of rearrangements raises the possibility of developing anti-idiotypic antibodies or even hapten/antigen–binding cytotoxic drugs that could be used for the targeted delivery of therapeutic agents to leukemic cells.

Footnotes

See the related article beginning on page 1008.

Nonstandard abbreviations used: B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL); complementarity-determining region (CDR); essential mixed cryoglobulinemia (EMC); hepatitis C virus (HCV).

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Harris NL, et al. A revised European-American classification of lymphoid neoplasms: a proposal from the International Lymphoma Study Group. Blood. 1994;84:1361–1392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris NL, et al. World Health Organization classification of neoplastic diseases of the hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues: report of the Clinical Advisory Committee meeting-Airlie House, Virginia, November 1997. J. Clin. Oncol. 1999;17:3835–3849. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.12.3835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Binet JL, et al. A new prognostic classification of chronic lymphocytic leukemia derived from a multivariate survival analysis. Cancer. 1981;48:198–206. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810701)48:1<198::aid-cncr2820480131>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rai KR, et al. Clinical staging of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 1975;46:219–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matutes E, et al. The immunological profile of B-cell disorders and proposal of a scoring system for the diagnosis of CLL. Leukemia. 8:1640–1645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCarthy H, et al. High expression of activation-induced cytidine deaminase (AID) and splice variants is a distinctive feature of poor-prognosis chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2003;101:4903–4908. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamblin TJ, Davis Z, Gardiner A, Oscier DG, Stevenson FK. Unmutated Ig V(H) genes are associated with a more aggressive form of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 1999;94:1848–1854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Damle RN, et al. Ig V gene mutation status and CD38 expression as novel prognostic indicators in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 1999;94:1840–1847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naylor M, Capra JD. Mutational status of Ig V(H) genes provides clinically valuable information in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 1999;94:1837–1839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gurrieri C, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells can undergo somatic hypermutation and intraclonal immunoglobulin V(H)DJ(H) gene diversification. J. Exp. Med. 2002;196:629–639. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zupo S, et al. CD38 expression distinguishes two groups of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemias with different responses to anti-IgM antibodies and propensity to apoptosis. Blood. 1996;88:1365–1374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen L, et al. Expression of ZAP-70 is associated with increased B-cell receptor signaling in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 100:4609–4614. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krober A, et al. V(H) mutation status, CD38 expression level, genomic aberrations, and survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2002;100:1410–1416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosenwald A, et al. Relation of gene expression phenotype to immunoglobulin mutation genotype in B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J. Exp. Med. 2001;194:1639–1647. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.11.1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klein U, et al. Gene expression profiling of B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia reveals a homogeneous phenotype related to memory B cells. J. Exp. Med. 2001;194:1625–1638. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.11.1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghiotto F, et al. Remarkably similar antigen receptors among a subset of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J. Clin. Invest. 2004;113:1008–1016. doi:10.1172/JCI200419399. doi: 10.1172/JCI19399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fais F, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells express restricted sets of mutated and unmutated antigen receptors. J. Clin. Invest. 1998;102:1515–1525. doi: 10.1172/JCI3009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson TA, Rassenti LZ, Kipps TJ. Ig VH1 genes expressed in B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia exhibit distinctive molecular features. J. Immunol. 1997;158:235–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keating, M.J., et al. 2003. Biology and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Hematology (Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program). 153–175. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Chiorazzi N, Ferrarini M. B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: lessons learned from studies of the B cell antigen receptor. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2003;21:841–894. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Potter KN, et al. Features of the overexpressed V1-69 genes in the unmutated subset of chronic lymphocytic leukemia are distinct from those in the healthy elderly repertoire. Blood. 2003;101:3082–3084. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dammacco F, Sansonno D. Antibodies to hepatitis C virus in essential mixed cryoglobulinaemia. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1992;87:352–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb03001.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pascual M, Perrin L, Giostra E, Schifferli JA. Hepatitis C virus in patients with cryoglobulinemia type II. J. Infect. Dis. 1990;162:569–570. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.2.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan CH, Hadlock KG, Foung SK, Levy S. V(H)1-69 gene is preferentially used by hepatitis C virus-associated B cell lymphomas and by normal B cells responding to the E2 viral antigen. Blood. 2001;97:1023–1026. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.4.1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gharagozloo S, Khoshnoodi J, Shokri F. Hepatitis C virus infection in patients with essential mixed cryoglobulinemia, multiple myeloma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2001;7:135–139. doi: 10.1007/BF03032580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Capra JD, Klapper DG. Complete amino acid sequence of the variable domains of two human IgM anti-gamma globulins (Lay/Pom) with shared idiotypic specificities. Scand. J. Immunol. 1976;5:677–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1976.tb03017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Capra JD, Kehoe JM. Structure of antibodies with shared idiotypy: the complete sequence of the heavy chain variable regions of two immunoglobulin M anti-gamma globulins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1974;71:4032–4036. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.10.4032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanz I, Capra JD. V kappa and J kappa gene segments of A/J Ars-A antibodies: somatic recombination generates the essential arginine at the junction of the variable and joining regions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1987;84:1085–1089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.4.1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hasemann CA, Capra JD. Mutational analysis of arsonate binding by a CRIA+ antibody. VH and VL junctional diversity are essential for binding activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:7626–7632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hasemann CA, Capra JD. Mutational analysis of the cross-reactive idiotype of the A strain mouse. J. Immunol. 1991;147:3170–3179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rathbun G, Sanz I, Meek K, Tucker P, Capra JD. The molecular genetics of the arsonate idiotypic system of A/J mice. Adv. Immunol. 1988;42:95–164. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60843-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meek K, Sanz I, Rathbun G, Nisonoff A, Capra JD. Identity of the V kappa 10-Ars-A gene segments of the A/J and BALB/c strains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1987;84:6244–6248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.17.6244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Humphries CG, et al. A new human immunoglobulin VH family preferentially rearranged in immature B-cell tumours. Nature. 1988;331:446–449. doi: 10.1038/331446a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lieberman R, Potter M, Mushinski EB, Humphrey W, Jr, Rudikoff S. Genetics of a new IgVH (T15 idiotype) marker in the mouse regulating natural antibody to phosphorylcholine. J. Exp. Med. 1974;139:983–1001. doi: 10.1084/jem.139.4.983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin F, Oliver AM, Kearney JF. Marginal zone and B1 B cells unite in the early response against T-independent blood-borne particulate antigens. Immunity. 2001;14:617–629. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vinuesa CG, et al. Recirculating and germinal center B cells differentiate into cells responsive to polysaccharide antigens. Eur. J. Immunol. 2003;33:297–305. doi: 10.1002/immu.200310003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Guinamard R, Okigaki M, Schlessinger J, Ravetch JV. Absence of marginal zone B cells in Pyk-2-deficient mice defines their role in the humoral response. Nat. Immunol. 2000;1:31–36. doi: 10.1038/76882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fagarasan S, Honjo T. T-independent immune response: new aspects of B cell biology. Science. 2000;290:89–92. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5489.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]