Abstract

Background:

Thalassemia is a genetic disorder of hemoglobin synthesis, which requires regular blood transfusion therapy leading to iron overload in the body tissues. Transfusional hemosiderosis is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in these patients. Reliable methods for evaluation of iron overload are either invasive, costly or remotely available. Therefore, a simple technique of monitoring iron overload is desirable.

Aim:

To know whether iron can be demonstrated in exfoliated buccal cells of β-thalassemia major patients using Perls’ Prussian blue method and to correlate it with serum ferritin levels.

Materials and Methods:

Smears were obtained from buccal mucosa of 60 randomly selected β-thalassemia major patients and 30 healthy subjects as controls. Smears were stained with Perls’ Prussian blue method. Blood samples were taken for estimation of serum ferritin levels.

Statistical Analysis:

Chi-square, Mann-Whitney, and Spearman Rank's Correlation tests.

Results:

Perls’ positivity was observed in 71.7% of thalassemic patients with a moderately positive correlation to serum ferritin levels.

Conclusion:

Oral exfoliative cytology can be a useful tool in demonstration of iron overload in thalassemic patients, however, further research in this field in the direction of quantification of these procedures is required, which can establish this non-invasive procedure as an ideal screening tool.

Keywords: Iron overload, oral exfoliative cytology, Perls’ Prussian blue staining, thalassemia

Introduction

The thalassemias are a heterogeneous group of genetic disorders of hemoglobin synthesis, all of which result from a reduced rate of production of one or more of the globin chains of hemoglobin.[1] In the homozygous state β-thalassemia genes result in a severe or total suppression of β-chain synthesis clinically characterized as thalassemia major or Cooley's anemia.[2] β-thalassemia major is a life threatening condition, characterized by severe anemia, hepatosplenomegaly, growth retardation, endocrine dysfunction and skeletal changes due to hypertrophy, and expansion of the hematopoietic marrow.[3] As anemia is usually pronounced in persons with the major form of the disease, the patient requires frequent blood transfusions to overcome the effects of anemia.[4] Repeated blood transfusions, ineffective erythropoiesis, and increased gastrointestinal iron absorption lead to iron overload in the body. Iron overload is the life limiting complication commonly found in the thalassemics. The iron burden on the body can be estimated by means of the serum ferritin, serum iron, and total iron binding capacity levels. The estimation of serum ferritin level is the most commonly employed test to evaluate iron overload in β-thalassemia major. Liver iron correlates closely with the total body iron in transfusional iron overload.[5] Measurement of the iron concentration in a liver biopsy specimen is a reference method for assessing the body iron stores. Other methods for evaluation of hepatic iron include superconducting-quantum-interference-device (SQUID), liver magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and magnetic spectrometry.[5,6] The discomfort and the potential risk associated with the liver biopsy procedure as well as the availability and cost factor associated with MRI and SQUID have prompted us to search for non-invasive and cheaper method for evaluation of iron stores. Exfoliative cytology is a non-invasive as well as cheaper method, which is being used for various diseases as in malignancy. In our study, we wanted to see whether exfoliative cytology could be a useful tool in detection and monitoring of iron overload in β-thalassemia major patients. We have applied Perls’ Prussian blue staining procedure for demonstration of iron granules in exfoliated buccal cells of β-thalassemia major patients considering that the exfoliated buccal cells may also represent changes in the underlying parent tissue.

Aims and objectives

To assess iron overload in β-thalassemia major patients by oral exfoliative cytology using Perls’ Prussian blue stain.

To correlate Perls’ Prussian blue staining with serum ferritin levels.

To ascertain whether exfoliative cytology can be used as a screening and diagnostic tool for detection of iron overload in β-thalassemia major patients.

Materials and Methods

The study was conducted in patients visiting thalassemia ward and Department of Pedodontia, after approval from Institutional Ethical Committee. The sample selection was done by simple random sampling technique in accordance with inclusion and exclusion criteria. The study sample comprised of 90 patients broadly classified into two groups.

The study group comprised of 60 β-thalassemia major patients, out of which 38 were males and 22 females, ranging in the age group of 1-16 years with an average age of 7.28 years. The subjects were included based on confirmation by hemoglobin electrophoresis or high performance liquid chromatography and receiving regular blood transfusions. Subjects with history of any other major illness and newly diagnosed cases yet to receive a blood transfusion were excluded from the study.

The control group comprised of 30 clinically healthy individuals, out of which 16 were males and 14 were females, in the age range of 2-16 years and an average age of 7.66 years. Subjects were included on the basis of history, clinical examination and blood investigations within normal range. The subjects with history of any major illness, blood transfusion; any clinically observable intraoral lesion, and abnormal blood investigations were excluded.

Blood samples were withdrawn from both the study as well as control group subjects in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid and plain vials for the estimation of hemogram, peripheral blood smear examination, and serum ferritin levels. Buccal smears were obtained from each subject of both groups following standard protocol. Smears were fixed in 90% alcohol for 1 h and subsequently stained with Perls’ Prussian blue method[7] and were evaluated under the microscope at ×100 and ×400 magnification.

Results

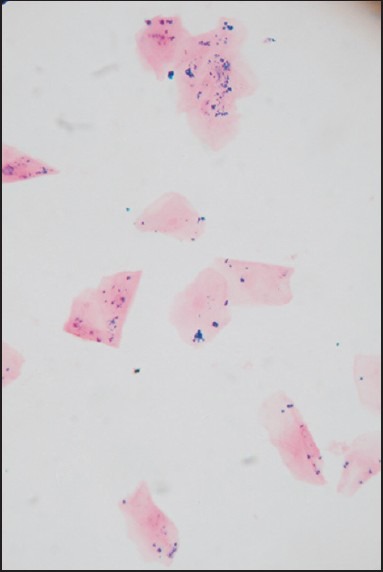

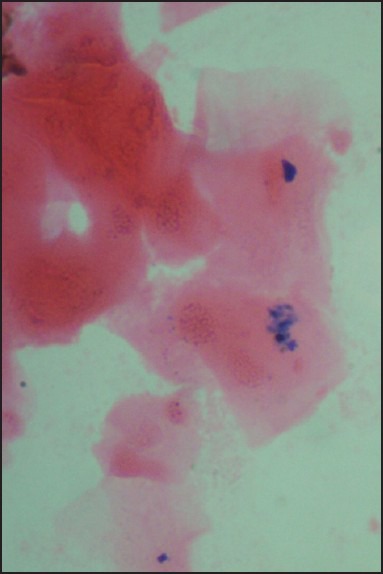

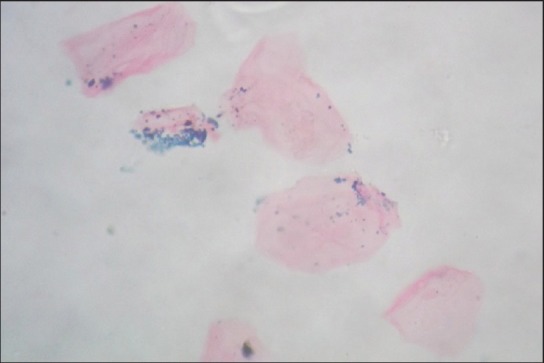

Smears which showed the presence of blue colored fine dispersed to mild clumps of intracellular granules under ×100 and ×400 magnification were considered as positive [Figures 1–3].

Figure 1.

Smear showing blue colored dispersed intracellular granules (Perls’ Prussian blue stain, ×100)

Figure 3.

Smear at higher magnification showing clumps of blue colored granules (Perls’ Prussian blue stain, x400)

Figure 2.

Smear at higher magnification showing dispersed blue colored granules (Perls’ Prussian blue stain, ×400)

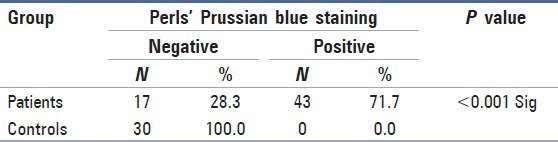

Perls’ Prussian blue staining was detected to be positive in 71.7% in the study group while none of the subjects in the control group revealed positivity. Chi-square test was carried out to compare Perls’ Prussian blue staining positivity in the study and control group. This was statistically significant (P < 0.001) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Comparison of Perls’ Prussian blue reaction in β-thalassemic patients and control subjects

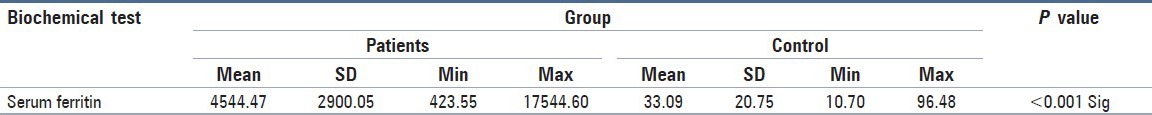

The serum ferritin level was significantly higher in the study group as compared to control subjects. The mean ± SD serum ferritin level in patients and control subjects was 4544.47 ± 2900.05 ng/mL and 33.09 ± 20.75 ng/mL respectively. Comparison of mean values among study and control group was carried out using the Mann Whitney U-test (P < 0.001) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparison of serum ferritin levels in β-thalassemic patients and control subjects

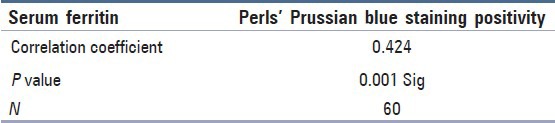

Correlation of Perls’ Prussian positivity with serum ferritin levels was carried out using the Spearman Rank's correlation test. Perls’ Prussian blue staining and serum ferritin levels had moderately significant positive correlation (Correlation coefficient = 0.424). Chi-square test was applied to know the significance of the test (P = 0.001) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Spearman Rank's correlation of Perl's Prussian staining positivity and serum ferritin levels in β-thalassemic patients

Discussion

β-thalassemia is a hereditary blood disorder that results in a failure to produce β-globin chain, and as a consequence, normal hemoglobin cannot be synthesized. In addition, there is ineffective erythropoiesis because of excess of α-globin chains; these damage the red cell membrane, resulting in cell lysis and an increased breakdown of red cells, which leads to severe anemia.[8] Majority of the patients of thalassemia presents the symptoms by the age of 1 year. From then, they undergo regular blood transfusions one to two times in a month to maintain a hemoglobin levels of 9-10 g/dL. The progressive iron overload in β-thalassemia major patients is the consequence of ineffective erythropoiesis, increased gastrointestinal absorption of iron, lack of physiologic mechanism for excreting excess iron, and above all multiple transfusions.[5] Transfusional hemosiderosis is the major cause of late morbidity and mortality in patients with thalassemia major.[9]

Storage iron occurs in two forms-ferritin and hemosiderin; ferritin is normally predominant. In a normal person, storage iron is divided about equally between the reticuloendothelial cells (mainly in spleen, liver and bone marrow), hepatic parenchymal cells and skeletal muscles. Hemosiderin, the main storage form is more stable and less readily mobilized for hemoglobin formation than ferritin, which predominates in hepatocytes. In states of iron overload, hemosiderin increases to a greater degree than ferritin and becomes the dominant form. Hemosiderin contains more iron than ferritin (25-40%).[10]

Perls’ Prussian blue reaction is considered the first classical histochemical reaction, which is widely applied in the field of hematology. Treatment with an acid ferrocyanide results in unmasking of ferric iron in the form of hydroxide [Fe(OH)3] by dilute hydrochloric acid. The ferric iron then reacts with a dilute potassium ferrocyanide solution to produce an insoluble blue compound, ferric ferrocyanide (Prussian blue).[7]

In our study, exfoliated cells from the buccal mucosa of 43 of the 60 thalassemic patients (71.7%) group revealed positivity for Perls’ Prussian blue reaction. Chi-square test was applied, the P value was <0.001, and the test was considered significant. Further, we observed that none of our control subjects showed Perls’ Prussian blue positivity.

Our results were similar as those observed by Nandprasad et al.,[11] who recorded 65% Perls’ postivity although these were lower than those of Gururaj and Sundharam,[12] who observed 100% Perls’ positivity.

The serum ferritin levels were significantly higher in our study group as compared to control group. The tremendous rise in serum ferritin levels in the study group was in accordance with those reported by various authors. The mean serum ferritin levels reported in previous studies were 3820 ng/mL by Silvilairat et al.,[13] and 3390 ng/mL by Ikram et al.[5] It was observed from our study and various other authors that serum ferritin is markedly elevated in β-thalassemic patients and a great variation in serum ferritin levels was observed in these patients. This may be related to different factors such as age of patient, severity of disease, age of onset of blood transfusions, number and regularity of blood transfusions, use of chelation therapy and other systemic and metabolic factors.

In our study, we ascertained the correlation of Perls’ Prussian positivity to serum ferritin. Our results showed a moderately positive correlation, which indicates that the positive staining in exfoliated buccal cells may give us a clue of increased serum ferritin levels and thus, indicating iron overload in the body tissues.

Even though, few authors have evaluated Perls’ Prussian blue staining in exfoliated buccal cells, as far as we are aware, this is the first study in which correlation of Perls’ Prussian blue positivity is carried out with serum ferritin levels. The exact reason for non-positivity of Perls’ Prussian blue staining in 100% cases and a moderate correlation to serum ferritin levels can be hypothetically explained based on iron metabolism.

The excess amount of iron in the blood that gets accumulated in various tissues may depend upon various factors including the formation of iron storage pool. Moreover, amount of apoferritin and therefore, ferritin formed in exfoliated buccal cells, may vary as well as there may be variation in the amount of hemosiderin formed, which may invariably affect the Perl's positivity. When iron overload results from the increased catabolism of erythrocytes as in case of transfusional iron overload, iron accumulates in reticuloendothelial macrophages first and only later spills over into parenchymal cells.[14]

Ferritin although may be present in the cells, cannot be visualized under light microscope and it can be observed in the electron microscope only. Hemosiderin, because of its larger size, can be visualized under light microscope as blue colored granules in the cytoplasm of the cell. Hemosiderin is supposed to be formed when the quantity of iron exceeds the apoferritin storage pool or as the ferritin molecule ages.[15]

Detection of serum ferritin is a most commonly used method for the assessment of iron overload, although it has some limitations. It is an indirect measurement of iron burden and it can be influenced by complications (e.g., infection, inflammation, ascorbate deficiency) and it require serial measurements and/or interpretation with other indicators of iron overload.[16]

Further, elaborative studies on a larger sample size for correlation of Perls’ Prussian blue staining with more reliable methods such as liver biopsy and MRI, besides biochemical methods, and quantification of iron granules is needed. Refinement of the technique for increased sensitivity and specificity with quantification should be the goal of these studies. Considering the simplicity and acceptability of exfoliative cytology methods, advancement in this field is genuinely advocated.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Weatherall DJ. Hemoglobin and the inherited disorders of globin synthesis. In: Hoffbrand AV, Catovsky D, Tuddenham EG, editors. Postgraduate hematology. 5th ed. Slovenia: Blackwell Publishing; 2005. pp. 85–103. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siamopoulou-Mavridou A, Mavridis A, Galanakis E, Vasakos S, Fatourou H, Lapatsanis P. Flow rate and chemistry of parotid saliva related to dental caries and gingivitis in patients with thalassaemia major. Int J Paediatr Dent. 1992;2:93–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263x.1992.tb00016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abu Alhaija ES, Al-Wahadni AM, Al-Omari MA. Uvulo-glosso-pharyngeal dimensions in subjects with beta-thalassaemia major. Eur J Orthod. 2002;24:699–703. doi: 10.1093/ejo/24.6.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silver HK. Mediterranean anemia. Calif Med. 1952;76:162–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ikram N, Hassan K, Younas M, Amanat S. Ferritin levels in patients of beta thalassemia major. Int J Pathol. 2004;2:71–4. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Angelucci E, Brittenham GM, McLaren CE, Ripalti M, Baronciani D, Giardini C, et al. Hepatic iron concentration and total body iron stores in thalassemia major. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:327–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008033430503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Churukian CJ. Pigments and minerals. In: Bancroft JD, Gamble M, editors. Theory and practice of histological techniques. 6th ed. China: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier Ltd; 2008. pp. 233–6. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Al-Wahadni A, Qudeimat MA, Al-Omari M. Dental arch morphological and dimensional characteristics in Jordanian children and young adults with beta-thalassaemia major. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2005;15:98–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2005.00585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prabhu R, Prabhu P, Prabhu RS. Iron overload in beta thalassemia-A review. J Biosci Technol. 2009;1:20–31. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Firkin F, Chesterman C, Pennington D, Rush B, editors. 5th ed. Noida, India: Blackwell Publishing; 1989. de Gruchy's clinical hematology in medical practice. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nandprasad S, Sharada P, Vidya M, Karkera B, Hemanth M, Prakash N. Oral exfoliative cytology in beta thalassemia patients undergoing repeated blood transfusions. Internet J Pathol. 2009;10:7. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gururaj N, Sundharam S. Demonstration of iron in the exfoliated cells of the oral mucosa. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2003;1:37–9. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Silvilairat S, Sittiwangkul R, Pongprot Y, Charoenkwan P, Phornphutkul C. Tissue Doppler echocardiography reliably reflects severity of iron overload in pediatric patients with beta thalassemia. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2008;9:368–72. doi: 10.1016/j.euje.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andrews NC. Disorders of iron metabolism. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1986–95. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199912233412607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guyton AC, Hall JE. Guyton & Hall Textbook of physiology. 9th ed. New Delhi India: Prism Books Pvt. Ltd; 1996. Red blood cells, anemia and polycythemia; pp. 353–71. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brownee JA, Carson SM, Mckiernan P. Nursing consideration in the management of patients with chronic transfusional iron overload. A supplement to oncology nurse advisor. [Last accessed on 2010 May 2-4]. Available from: http://www.oncologynurseadvisor.com .