Abstract

Background:

Current data regarding infertility suggests that male factor contributes up to 30% of the total cases of infertility. Semen analysis reveals the presence of spermatozoa as well as a number of non-sperm cells, presently being mentioned in routine semen report as “round cells” without further differentiating them into leucocytes or immature germ cells.

Aim:

The aim of this work was to study a simple, cost-effective, and convenient method for differentiating the round cells in semen into immature germ cells and leucocytes and correlating them with total sperm counts and motility.

Materials and Methods:

Semen samples from 120 males, who had come for investigation for infertility, were collected, semen parameters recorded, and stained smears studied for different round cells. Statistical analysis of the data was done to correlate total sperm counts and sperm motility with the occurrence of immature germ cells and leucocytes. The average shedding of immature germ cells in different groups with normal and low sperm counts was compared. The clinical significance of “round cells” in semen and their differentiation into leucocytes and immature germ cells are discussed.

Conclusions:

Round cells in semen can be differentiated into immature germ cells and leucocytes using simple staining methods. The differential counts mentioned in a semen report give valuable and clinically relevant information. In this study, we observed a negative correlation between total count and immature germ cells, as well as sperm motility and shedding of immature germ cells. The latter was statistically significant with a P value 0.000.

Keywords: Immature germ cells, round cells, semen, total sperm count

Introduction

Reproduction is the fundamental biological process of life essential for the continuation of the species. It depends on the fertility status of the male and female partners involved. As the prevalence of infertility is increasing, the brunt of infertility management is felt by the medical field. Worldwide surveys have shown that almost one in every seven couples faces problems of infertility. In India, the infertility rate is 9% of the reproductive population, which means almost 12 to 18 million couples visit infertility clinics annually for treatment. Of the total infertility cases, 50% are due to the male factors. Hence, in andrology, rapid advances with a lot of sophisticated and expensive newer diagnostic methods are emerging. This requires a very sophisticated infrastructure and trained personnel which may not be available at peripheral medical centers. Further this battery of investigations leads to a huge financial burden on the couple as well as the society which is beyond the reach of the economically compromised population in a developing country like India. In such a scenario, semen analysis forms the basic, cost-effective, and non-invasive investigation for screening of such a large number of patients.

In a semen sample, apart from spermatozoa there may be a variable number of non-sperm cells. In a routine semen report, they are mentioned as “round cells” without further differentiating them into leucocytes or immature germ cells. This could be because of the difficulty in identifying and differentiating those cells in an unstained wet preparation.[1] They could be either inflammatory cells, most commonly leucocytes or cells of immature spermatogenic series. The WHO manual for semen analysis quotes that if the round cells are more than 1 × 106/mL, they should be differentiated to see for leucocytes.[2] Review of the literature clearly indicates that a differentiation of “round cells” into cells of spermatogenic and non-spermatogenic origins is important for a more accurate semen report.[3,4,5] The inclusion of all “round cells” into one group may increase the risk of misinforming the treating clinician.[6] Hence, there is a need for initial screening and differentiation of round cells into immature germ cells and leucocytes with a simple and cost-effective method. The aim of the present work was to study the round cells by a simple staining method and their differentiation and quantification into leucocytes and immature germ cells and then comparing these with sperm counts and motility.

Materials and Methods

Semen jars, glass slides, centrifuge, fixative, Leishman stain, and microscope with an oil immersion lens were used. After the approval of the ethical committee, primary data was collected. It comprised of 120 semen samples collected in the laboratory from males coming for semen analysis for routine infertility work-up, at the Medical College Hospital laboratory and other private laboratories on request during the period of 24 months starting from August, 2009. A written, informed consent was obtained prior to collection and samples were collected by masturbation into a clean wide-mouthed plastic semen container. Semen parameters were recorded. Using a drop of semen, smears were prepared by the feathering method given in the 5th edition of the WHO manual for semen analysis.[7] Smears were stained by the standard staining method using Leishman stain.[8,9,10] The round cells were counted and differentiated into immature germ cells and leucocytes. The data was tabulated in the master chart.

Results

Routine semen parameters like the total count and motility were recorded. Smears in duplicate were seen under oil immersion lens of microscope for differential counts of round cells into immature germ cells and leucocytes. Cells were identified according to their size, shape, and morphology.[3,6]

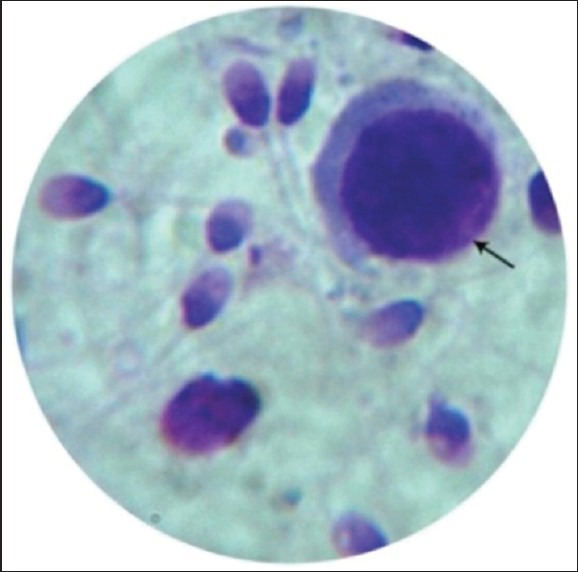

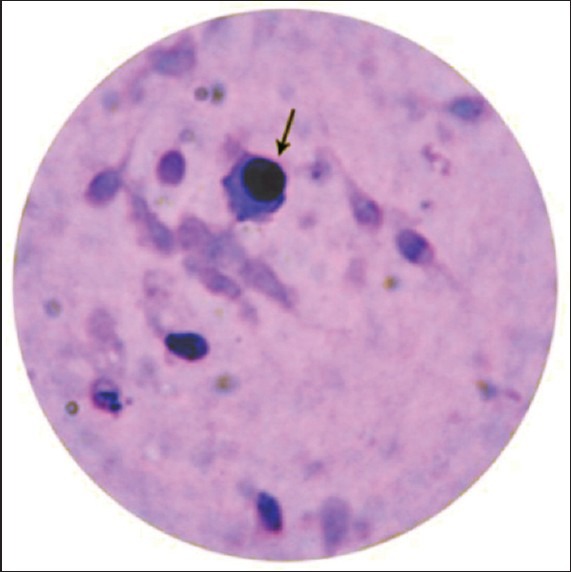

Immature germ cells mainly seen were primary spermatocytes, identified by their large size, large spherical nucleus with wooly appearance and evenly distributed chromatin granules [Figure 1]. The next common were spermatids which were smaller, round to oval cells with a dark nucleus [Figure 2]. Sometimes occasional bi-nucleate cells— secondary spermatocytes—were also seen. Leucocytes were differentiated by their smaller size and multilobed nuclei.

Figure 1.

Primary spermatocytes (Leishman stain, ×100)

Figure 2.

Spermatid (Leishman stain, ×100)

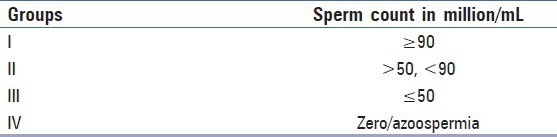

The cases were divided into four groups based on total sperm counts as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Distribution of cases according to total sperm counts

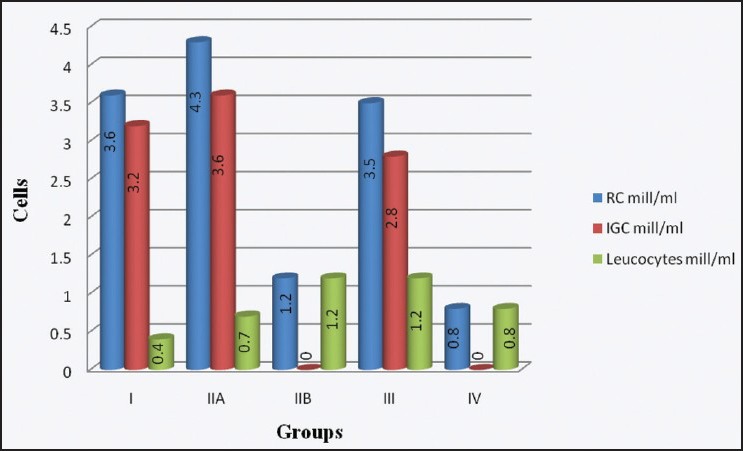

The differential counts in each group are shown in Graph 1. Group II was further divided into group IIA , which showed immature germ cells and group IIB which showed only leucocytes. It was seen that in group I and group IIA, which had a normal total count, the average number of round cells were 3.6 and 4.3 million/mL out of which average number of immature germ cells were 3.2 and 3.6 million/mL, respectively. While in group III, the round cells were 3.5 million/mL out of which 2.8 million/mL were immature germ cells. In group IIB, there were no immature germ cell rather all leucocytes with an average of 1.2 million/mL. In group IV, having azoospermic cases there were 0.8 million/mL round cells in which all were leucocytes and no germ cells were seen. In all other groups, the number of leucocytes averaged between 0.4 and 0.8 million/mL.

Graph 1.

Distribution of round cells (RC) – Immature germ cells (IGC) and leucocytes

Statistical Analysis

The round cells were counted as percentage of the total count and it was seen that their percentage went on increasing as the total counts went on decreasing. Statistical analysis of correlation showed that there was weak negative correlation between immature germ cells and total counts with Pearson correlation coefficient −0.130 and the X2 test showed no statistical significance, P = 0.128.

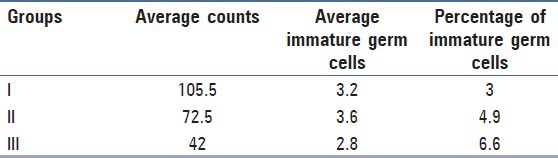

The percentage of immature germ cells steadily increased as the total counts decreased. The total count was compared with the immature germ cells expressed as percentage of the total count, it showed negative correlation and the results were such that the ratio of germ cells to total counts is more informative than the germ cell counts alone [Table 2].

Table 2.

Group-wise distribution of percentage of immature germ cells

There was a negative correlation between motility and sperm count with a correlation coefficient of −0.441 and was statistically significant by the X2 test with P = 0.00.

The occurrence of leucocytes was correlated with total sperm counts and showed a negative correlation with Pearson correlation coefficient being −0.262.

Discussion

In clinical andrology, the basic investigation for male infertility is semen analysis which gives a lot of information. In this study, our results showed that all the patients had round cells in their semen in the range between 2.8% and 8.2% of the total count. Our results are comparable to the study by Fedder et al.[3] who mention that non-sperm cells form less than 15% of the total count. The round cells were further studied by using a simple staining method---Leishman stain. The review article by Johanisson et al.[9] which evaluates the morphological differences between “round cells” in semen states that, there is no difference between the size and shape of neutrophils as seen on peripheral blood smears and stained semen smears. The Leishman stain is routinely used in the laboratories for staining blood smears and the pathologist is well versed with the methodology. Keeping this in mind we have used the Leishman stain for the differential counts in semen.[8]

The differential counts of round cells showed that out of the total round cells, 80% to 90% were immature germ cells and 10% to 20% were leucocytes. The studies by Fedder et al.,[3] Gandini et al.,[1] and Ariagno et al.,[11] reported similar values. When the total count and occurrence of germ cells was correlated it showed a negative correlation. This compares favorably with a study by Fedder et al.[3]

Our results of correlation between germ cells and motility are also similar to those observed by Auroux et al.[12] who found a negative correlation between number of non-sperm cells and initial sperm motility and a positive correlation between immature seminal line elements and teratozoospermia. Hence, the presence of immature germ cells and low motility can be the cause of male sub-fertility in spite of normal sperm counts. The inclusion of immature germ cell concentration in every semen analysis report will definitely be a useful tool in the diagnosis of the cause of infertility. Moreover, the counting of these cells could be a good indicator of a dysfunction at the testicular level. It may give us information about germ cell maturation arrest which is associated with increased shedding of germ cells from spermatogonia to spermatocytes and spermatids in semen.

The occurrence of leucocytes was correlated with total sperm counts and showed a negative correlation, such a negative correlation was also seen in the study done by Politich et al.[13] The findings in a study by Wolff[14] mention that the prevalence of leucocytospermia more than 106/mL was seen in approximately 10-20% of patients of male infertility and the presence of white blood cells (WBCs) can affect sperm function. According to WHO manual, 1 × 106/mL is considered the threshold value for leucocytes in semen. The results in our study can be suggestive of inflammatory condition of male genital tract. Thus, this simple, cost-effective test can aid the diagnosis and justify the use of antibiotics.

The inclusion of immature germ cells and leucocytes in the semen analysis done for the initial screening of patients of male sub-fertility can help to categorize the patients. Depending on this, those having leucocytospermia can be subjected to further investigations like reactive oxygen species or immunofluorescence microscopy. Some patients are sub-fertile even when the sperm counts are normal and may have high immature germ cell counts. These patients can be segregated and further analyzed for cytogenetic studies for sperm deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) damage or DNA fragmentation index which may be the cause of sub-fertility.[15] This will enable the use of sophisticated and expensive tests on a select group of cases, hence reduce the financial burden on the patients as well as work load on the laboratories.

The method of staining the centrifuged pellet of semen can be used in samples from non-obstructive azoospermic patients. This can be a very simple method to identify germ cells in these cases. In this study, there were six azoospermic samples all having absence of fructose and immature germ cells which confirmed obstructive azoospermia. Thus, the presence of germ cells can easily and definitely differentiate non-obstructive from obstructive azoospermia.[16]

Recent research in andrology has advanced to such an extent that the immature germ cells (spermatids) in semen samples from azoospermic cases can be injected into the oocyte by intra-cytoplasmic sperm-injection technique producing viable embryos. This is really a boon for the azoospermics. The germ cells can also be identified and isolated, then used for in-vitro culture. By recent micro-manipulation techniques, these immature cells can be used for in-vitro fertilization.[17] These isolated germ cells can be studied by cytogenetics for chromosomal aberrations – numerical or structural. Various andrological pathologies like cryptorchidism and testicular cancers can be diagnosed, for example data regarding hyperploidia of chromosome one in seminoma and carcinoma in-situ of testis could aid the diagnosis by studying the germ cells in semen instead of going for invasive testicular biopsies.[1] Hence, the identification and isolation of immature germ cells can be useful for diagnosis, treatment, and research purposes.

To conclude, round cells and their differentiation into immature germ cells and leucocytes can add valuable and clinically relevant information to the semen report, which could be obtained by rather cheap yet quite rewarding simple staining procedures. The differential count must be included in every semen analysis report, which is performed as an initial screening test of the masses. In a developing country like India, with a huge load of patients, it serves as the cost-effective screening test so as to clinically evaluate and correlate infertile males so that only a select number of cases can be subjected to sophisticated, expensive, or invasive investigations as per the need. This reduces the social and economical burden on the couple and the family. The immature germ cells in semen can be identified, separated and isolated for diagnostic and cytogenetic studies. Furthermore, many studies can be undertaken from different parts of our country for correlation of germ cells with total count and motility, their further clinical follow-up regarding treatment and pregnancy outcome, and can be used in future for sperm micro-manipulation and in-vitro fertilization techniques.

Acknowledgments

It gives me great pleasure to express my deepest sense of gratitude to my revered teachers Dr. R. S. Humbarwadi, Dr. Mrs. Ashalata D. Patil and Dr. Mrs. Anita R. Gune, for their support throughout the study. I owe my thanks to all my colleagues at the Department of Anatomy and respected Dean, Dr. D. Y. Patil Medical College, Kolhapur.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Gandini L, Lenzi A, Lombardo F, Pacifici R, Dondero F. Immature germ cell separation using a modified discontinuous Percoll gradient technique in human semen. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:1022–7. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.4.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooper TG. Semen analysis: An overview. In: Kvist U, Bjo L, editors. Manual on Basic Semen Analysis. 4th ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2002. p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fedder J, Askjaer SA, Hjort T. Nonspermatozoal cells in semen: Relationship to other semen parameters and fertility status of the couple. Arch Androl. 1993;31:95–103. doi: 10.3109/01485019308988386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jassim A, Festenstein H. Immunological and morphological characterization of nucleated cells other than sperm in semen of oligospermic donors. J Reprod Immunol. 1987;11:77–89. doi: 10.1016/0165-0378(87)90013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tomlinson MI, Barratt CL, Bolton AE. Round cells and sperm fertilizing capacity: The presence of immature germ cells but not seminal leukocytes are associated with reduced success of in-vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 1992;58:1257–64. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)55583-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phadke AM, editor. 1st ed. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers; 2007. Clinical atlas of sperm morphology. [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. 5th ed. Geneva: WHO Press; 2010. WHO laboratory manual for the examination and processing of human semen. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dacie John V, Lewis SM. Preparation and staining methods for blood and bone-marrow films. In: Gorman J, editor. Practical Haematology. 8th ed. Hongkong: Churchill Livingstone; 1995. pp. 85–91. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johanisson E, Campana A, Luthi R, de Agostini A. Evaluation of ‘round cells’ in semen analysis: A comparative study. Hum Reprod Update. 2000;6:404–12. doi: 10.1093/humupd/6.4.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams MA, Wick A, Smith DC. The influence of staining procedure on differential round cell analysis in stained smears of human semen. Biotech Histochem. 1996;71:118–22. doi: 10.3109/10520299609117147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ariagno J, Curi S, Mendeluk G, Grinspon D, Repetto H, Chenio P, et al. Shedding of immature germ cells. Arch Androl. 2002;48:127–31. doi: 10.1080/014850102317267436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Auroux M. Nonspermatozoal cells in human sperm: A study of 1243 subfertile and 253 fertile men. Arch Androl. 1984;12:197–201. doi: 10.3109/01485018409161176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Politich JA, Wolff H, Hill JA, Anderson DJ. Comparison of methods to enumerate white blood cells in semen. Fertil Steril. 1993;60:372–5. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)56116-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolff H. The biologic significance of white blood cells in semen. Fertil Steril. 1995;63:1143–57. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)57588-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agarwal A, Bragais FM, Sabanegh E. Assessing sperm function. In: Nagler HM, editor. Urologic Clinics of North America: Male Infertility – Current Concepts and Controversies. Noida, U.P. India: Elsevier, Division of Reed Elsevier; 2008. pp. 157–71. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roy S, Banerjee A, Pandey HC, Singh G, Kumari GL. Application of seminal germ cell morphology and semen biochemistry in the diagnosis and management of azoospermic subjects. Asian J. Andrology. 2001 Jun;3:157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kahraman S, Polat G, Samli M. Multiple pregnancies obtained by testicular spermatid injection in combination with intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Human Reproduction. 1998;13:104–110. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]