Abstract

Background:

Dental students use extracted human teeth to learn practical and technical skills before they enter the clinical environment. In the present research, knowledge, performance, and attitudes toward sterilization/disinfection methods of extracted human teeth were evaluated in a selected group of Iranian dental students.

Materials and Methods:

In this descriptive cross-sectional study the subjects consisted of fourth-, fifth- and sixth-year dental students. Data were collected by questionnaires and analyzed by Fisher's exact test and Chi-squared test using SPSS 11.5.

Results:

In this study, 100 dental students participated. The average knowledge score was 15.9 ± 4.8. Based on the opinion of 81 students sodium hypochlorite was selected as suitable material for sterilization and 78 students believed that oven sterilization is a good way for the purpose. The average performance score was 4.1 ± 0.8, with 3.9 ± 1.7 and 4.3 ± 1.1 for males and females, respectively, with no significant differences between the two sexes. The maximum and minimum attitude scores were 60 and 25, with an average score of 53.1 ± 5.2.

Conclusion:

The results of this study indicated that knowledge, performance and attitude of dental students in relation to sterilization/disinfection methods of extracted human teeth were good. However, weaknesses were observed in relation to teaching and materials suitable for sterilization.

Keywords: Attitude, dental student, extracted human teeth, knowledge, performance

INTRODUCTION

Infection control is a critical aspect of dental practice, including subjects that are related to the health of dental practitioners, the dental staff and patients. Dental students must learn technical and preclinical skills before they enter the clinical environment and deliver care to patients. To this end, they use extracted human teeth to simulate, and practice different dental procedures.[1] In this context many manufactured instructional tools such as artificial plastic blocks and teeth on manikins and models are used to teach some endodontic procedures. However, these artificial tools are used in conditions where access to extracted teeth is limited or not possible. Furthermore, these artificial blocks cannot replace the natural human teeth in examinations, education, and research.[1,2] Regarding the importance of infection control and concerns echoed in the last few years, these extracted teeth have been noticed as a resource for infection. This fact prompts the investigators to evaluate the effects of disinfection/sterilization on extracted teeth.[1,3] Directives by the American Dental Association (ADA) and the Center for Disease Control (CDC) call for thorough removal of any organisms capable of transmitting disease from no-disposable items used in patient care. By implication, these directives include those materials used in simulated preclinical education that might have come in contact with blood or saliva. These body fluids are associated with extracted teeth routinely used by dental students in educational procedures to improve their clinical skills and techniques.[2,4,5]

It is obvious that many blood-borne pathogens, including hepatitis B virus (HBV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and bacterial pathogens, may be present in the pulp and radicular, and periradicular tissues of extracted human teeth.[2] Besides, tooth preparation procedures in the laboratory are generally carried out without a liquid coolant; therefore, there is a greater risk of exposure to pathogenic organisms in the laboratory and as a result there is the risk of contagion spread via aerosols and accidental penetrating wounds that might take place during handling of dental instruments.[4]

In addition, there are problems with the use of extracted human teeth because they are grossly contaminated, difficult to sterilize because of their structure, and might be damaged or altered by sterilization procedures.[4,6] The knowledge of dental students about infectious potential of extracted teeth used in preclinical practice was studied by Kumar et al.,[2] It was revealed from this study that about 90% of students know that extracted teeth are infection sources, but only 75% of them used a disinfection method to eliminate contamination from these teeth. Furthermore, most of the students used the boiling water and storing in sodium hypochlorite to sterilize these teeth.[2] Tate and White reported that formaldehyde is the only antiseptic solution that can achieve an effective antimicrobial concentration within the pulp space.[7] Furthermore, White and Hays demonstrated the inefficacy of ethylene oxide against Bacillus subtilis spores placed in the pulp chamber of extracted human molars.[8] White et al., showed that gamma radiation sterilizes teeth and endodontic filling materials without altering the structure and function of dentin; for complete sterilization, a dose of 173 k-rad with the help of a cesium radiation source was required.[9] Dominici et al.,[1] showed that only autoclaving for forty minutes at 240°F and 20 psi or soaking in 10% formalin for 1 week was 100% effective in preventing microbial growth. Pantera and Schuster reported that Rockal solution (benzalkonium chloride) for 24 h and 3 weeks did not eliminate microorganisms in teeth.[4]

Attam et al., reported that the chemical materials such as 2.6% sodium hypochlorite, 3% hydrogen peroxide and boiling water are not suitable and effective for disinfecting/sterilizing extracted human teeth.[10]

Since, there is no study about the knowledge, performance and attitude of dental students in relation to sterilization/disinfection methods of extracted human teeth used in preclinical courses, this study was designed to evaluate these parameters among a group of dental students of Kerman Dental School in Iran.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This descriptive cross-sectional study was carried out on fourth-, fifth- and sixth-year students at Kerman Dental School, Iran. Census sampling method was used for this study. A self-administered questionnaire was prepared based on previous studies,[1,2,4] which consisted of four parts (general questions, knowledge, attitude, and performance) about sterilization of extracted human teeth. In addition to questions regarding extracted teeth, the participants were asked questions about demographic data and personal information.

To examine the validity of the questionnaire, it was given to 10 specialist dental practitioners who were asked to indicate their level of agreement to the question statements using a five-point rating scale (extremely appropriate, appropriate, no idea, inappropriate, extremely inappropriate). As a result of the item analysis, some test questions were modified to improve clarity, and a discussion was held with each subject to validate the items of the questionnaire and apply the necessary changes to validate the questionnaire. Overall validity of the questionnaire was 79% and the validity of each question was 75-89%, which was acceptable. The reliability of the questionnaire was assessed using the Cronbach's alpha and gathering the replies provided by 15 students to the same questionnaire within a 15-day interval. Croenbach's coefficient for the reliability was 0.87, which was suitable for an acceptable study. After the analysis and discussion, the final questionnaire consisted of 34 questions in relation to knowledge, attitude, and performance in addition to questions about demographic data and personal information. The questionnaires were distributed among fourth-, fifth- and sixth-year students by the investigator. The goal of the study was explained and students were left alone to fill the questionnaire anonymously.

To score the knowledge and performance questions, each correct response was given a score of 2; each wrong one was given a score of 0 score; and no answer was given a score of 1. Attitude assessment questions had five possible responses (strongly disagree, disagree, neither agree nor disagree, agree, and strongly agree), where “strongly agree” was given a score of 5 and “strongly disagree” received a score of 1.

Chi-squared and Fisher's exact tests were employed to compare differences in knowledge, attitudes, and performance among the dental students. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS software version 11.5 and statistical significance was defined at P ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

Of 100 respondents, 60 (60%) were female and 40 (40%) were male. The mean age of the respondents was 24.1 ± 6.9 years (a range of 22-47 years). The results showed 56% of the respondents had no previous formal training in sterilization of extracted teeth and other students were trained about sterilization of extracted teeth in endodontic department. 65% of the participants declared that they were not asked to sterilize the extracted teeth. Furthermore, 87% of the respondents had worked on extracted human teeth and 82% of the participants thought that they need education regarding disinfection of these teeth. No relationship was noted between gender, year of education, sterilization training of extracted teeth, and responses to general questions (P > 0.05).

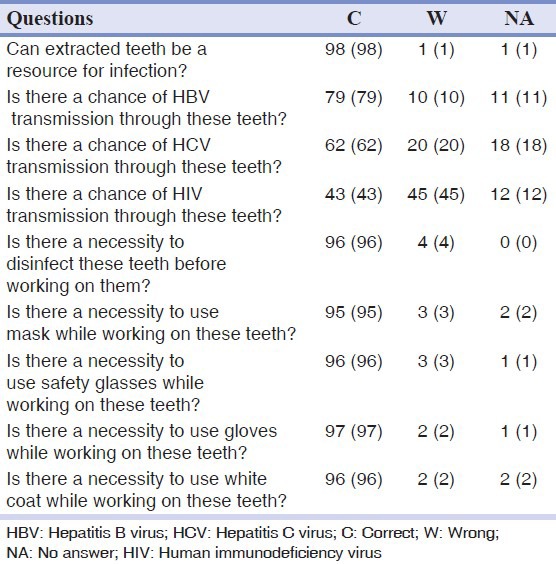

The total mean score for knowledge was 15.9 ± 4.8 (15.9 ± 2.2 and 15.3 ± 2.8 for males and females, respectively; range = 5-17), with no significant differences between males and females (P = 0.28) [Table 1]. Furthermore, no relationship was noted between year of education, trained about sterilization of extracted teeth and mean score for knowledge.

Table 1.

Awareness of dental students to knowledge questions

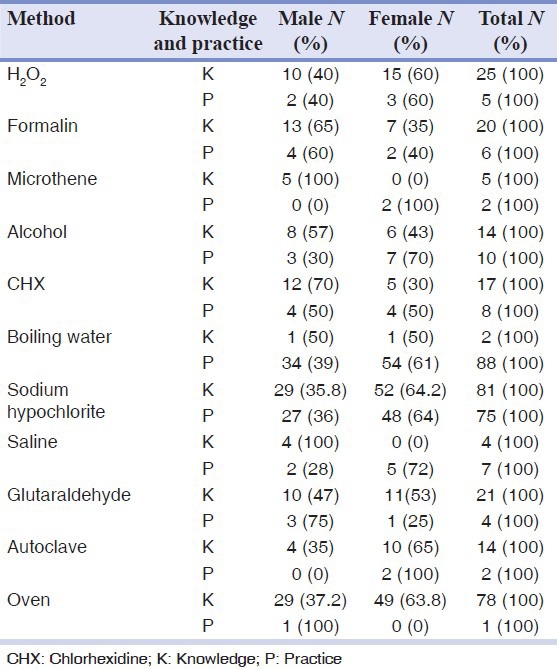

Regarding the question about respondents’ opinion on the most appropriate methods for disinfection or sterilization of extracted teeth, 81 students chose sodium hypochlorite and 78 chose dry oven. There was a significant difference between male and female participants in their preference in relation to the use of chlorhexidine. Thirty-four students chose one method, 28 persons chose two methods, 22 chose three methods and 16 students chose more than three methods for disinfection or sterilization of extracted teeth [Table 2]. The most commonly used method was boiling water and sodium hypochlorite. Minimum time spent on disinfecting these teeth was 0 and maximum time was 60 days. Sixty students used only one method, 16 used two methods, 3 used three methods and 3 used four methods while 18 students did not use any method to disinfect the extracted teeth.

Table 2.

Knowledge and practice of the student regarding sterilization of extracted teeth according by sex

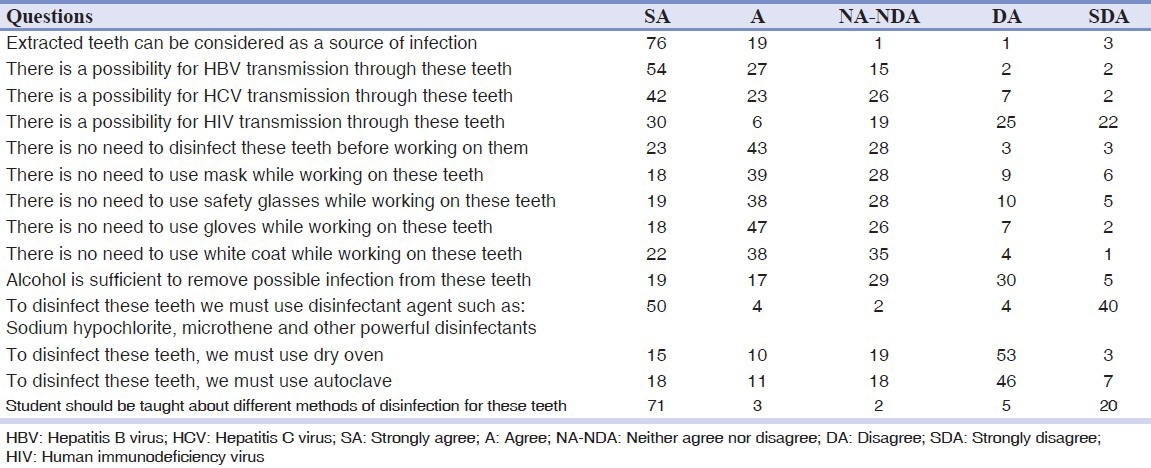

The total mean score for performance was 4.1 ± 0.8 (3.9 ± 1.7 and 4.3 ± 1.1 for males and females, respectively; a range of 1-5), with no significant differences between males and females. The results showed that 87% of the respondents disinfected extracted teeth before working on them and 79% of the participants used mask while working on these teeth, 84% used gloves, 61% used safety glasses, and 84% use white coat. Women were more careful while handling these teeth, due to significant differences in the use of gloves while working on the extracted teeth (P = 0.014). Furthermore, no relationship was noted between year of education, trained about sterilization of extracted teeth and total mean score for performance. The total mean score for attitude was 53.1 ± 5.2 (52.3 ± 8.1 and 54.1 ± 1.4 for males and females, respectively with a range of 25-60), with no significant differences between males and females (P = 0.35) [Table 3]. Furthermore, no relationship was noted between the years of education, trained about sterilization of extracted teeth, and total mean score for attitude.

Table 3.

Awareness of dental students to attitude questions

DISCUSSION

Based on universal precautions discussion, all body fluids and tissues must be treated as sources of infection for HIV, HBV, and hepatitis C virus, or other blood-borne pathogens. One part of the preclinical education in dentistry is teaching different procedures on extracted human teeth, which have been in direct contact with body fluids and are therefore dangerous sources for contamination.[7,11]

For a long time disease transmission has been a concern in medicine and dentistry. Some potential infection sources such as saliva, blood, and body fluids are present in clinical settings and consequently, they can exist in extracted stored teeth.[1] The Occupational Safety and Health Administration considers human teeth for the application in research and teaching purposes as potential sources of blood-borne pathogens.[12]

In the present study, the knowledge, performance, and attitudes of dental students were evaluated in relation to the use of these teeth and methods that they deemed appropriate to disinfect them.

Dental students had an acceptable knowledge level regarding methods of disinfection for extracted teeth, consistent with the findings of Kumar et al.,[2] In the present study, more than half of the students did not have any education about sterilization of extracted teeth, and were not asked to disinfect these teeth while working in the laboratory; however, in the study by Kumar et al.,[2] 87.5% of the dental students in Indian dental school were forced to sterilize the extracted teeth. This difference might be attributed to different educational programs that are held in two different dental schools; another reason might be that Indian education is more concerned about the infection of extracted teeth because of the higher prevalence of different diseases in this country.

Extracted teeth are a source of different infections; therefore, disinfection of these teeth seems essential to prevent dissemination of diseases. In order to sterilize and disinfect extracted human teeth, different methods can be used, including sodium chloramine, formalin, sodium hypochlorite, alcohol, glutaraldehyde, autoclaving, normal saline, freezing, 1:10 household bleach, ethylene oxide sterilization, and gamma radiation.[2,13]

In the present study, students chose dry oven and sodium hypochlorite as the best options to sterilize extracted teeth, although most of the students used boiling water, and storing in sodium hypochlorite to sterilize these teeth, which is consistent with Kumar et al.,[2] as in their study most of the students used sodium hypochlorite as the first option.

Sterilization process should not alter the physical properties of dentin and enamel and hence that the operating characteristics of the shear bonding and the sense of touch will be the same as clinical conditions. This process must also be able to remove harmful bacteria within the root canals.[7]

There are few studies assessing the methods used for disinfection and sterilization of extracted teeth. One key factor that should be considered while working on extracted teeth is that the time duration since the extraction can change the properties of these teeth while they are still a rich source for different infections.[14,15]

Tate and White reported that formaldehyde is the only antiseptic solution that can achieve an effective antimicrobial concentration within the pulp space. In addition, the only disinfectant solution that penetrates the pulp chamber is 10% formalin. It can be considered as an effective antimicrobial concentration.[7]

The effect of formalin storage on apical seal integrity of obturated canals was studied by George et al., It was shown that the rate of apical microleakage in the case group stored in formalin was much less than that in the control group. They also showed that this rate decreases for the extracted teeth in formalin in comparison to non-fixed specimens and this was significant.[16] This result is consistent with the findings of other studies.[8,17,18,19,20] Furthermore, formalin releases dangerous, and carcinogenic materials, which limit its application.[21,22]

White and Hays demonstrated the inefficiency of ethylene oxide against B. subtilis spores placed in the pulp chamber of extracted human molars. 64% of the teeth exposed to cold ethylene oxide treatment and 80% of the teeth exposed to the warm treatment still contained viable spore; therefore, ethylene oxide does not seem to be effective in eradicating infections from extracted teeth.[8] White et al., evaluated sterilization of extracted teeth by comparing gamma radiation with autoclaving, ethylene oxide, and dry heat. It was shown that gamma radiation sterilizes teeth and endodontic filling materials without altering the structure and function of dentin. For complete sterilization, a dose of 173 k-rad with the help of a cesium radiation source was required. Furthermore, no detectable changes were found with gamma irradiation, but all other methods introduced some detectable change in the spectra.[9]

Dominici et al.,[1] showed that only autoclaving for forty minutes at 240°F and 20 psi or soaking in 10% formalin for 1 week was 100% effective in preventing microbial growth. In addition, Kumar et al.,[2] showed that autoclaving at 121°C, 15 lbs psi for 30 min and immersion in 10% formalin for seven is effective in disinfecting/sterilizing extracted human teeth and chemicals like 2.6% sodium hypochlorite, 3% hydrogen peroxide, and boiling in water are not effective in disinfecting teeth.

White et al., showed by spectroscopic observation that autoclave does not lead to color changes in the teeth, but it increases the rate of light attraction by dentin. In addition, it was found that autoclave induces some changes in the dentin mineral and organic material.[9]

The cutting characteristics of extracted teeth were investigated by Parsell et al.,[23] Chandler[18] and Soares et al.,[19] Chandler[18] showed that autoclaving produced significant softening of bovine enamel, the changes in microhardness recorded being similar to those produced by some experimental cariogenic substrates. Gamma irradiation caused no significant changes in enamel hardness. Soares et al., showed that the mineral and organic dentin contents were more affected in autoclaved teeth than in the specimens stored in thymol.[19] It was reported that dentin hardness decreases by autoclaving; dentin of teeth autoclaved become softer in comparison to the control group.

The ADA and CDC suggest autoclaving as the best sterilization method for materials exposed to body fluids.[24] However, teeth can be damaged or altered by the sterilization process in an autoclave.[23,25] In relation to autoclaving, there is concern about its use for sterilization of extracted teeth with amalgam restorations as it may release mercury vapors in the air through autoclave exhaust and residual mercury contamination of the autoclave might occur.[24] It is also possible that the thermal cycling may cause teeth with amalgam restorations to fracture due to differences in their coefficient of thermal expansion;[11] therefore, autoclaving may not be a good option to sterilize extracted teeth that are going to be used for preclinical education.

Pantera and Schuster reported that Rockal solution (benzalkonium chloride) for 24 h and 3 weeks did not eliminate microorganisms in teeth. In their study, 5.25% sodium hypochlorite failed to disinfect the teeth in 5 min, but autoclaving for 40 min at a pressure of 15 psi and a temperature of 121°C destroyed all bacterial species.[4]

Attam et al., reported that the chemical materials such as 2.6% sodium hypochlorite, 3% hydrogen peroxide and boiling water are not suitable, and effective for disinfecting/sterilizing extracted human teeth.[10]

CDC recommends that the teeth used for educational and research purposes should be disinfected with sodium hypochlorite or liquid chemical germicides.[24] However, sodium hypochlorite can increase the porosity of human enamel by deproteinization.[26,27]

The present investigation revealed that there is not any relation between the year of education, trained about sterilization of extracted human teeth and total mean score for performance and knowledge. Since, the students in Kerman dental school are touched with extracted human teeth just at the third years of education; it is evidence that the number of the year in their education hasn’t any influence on their performance and knowledge. In the field of infection control teaching, cleaning with boiling water and sodium hypochlorite are touched only, such that it doesn’t have any effect on the students’ performance and knowledge. In this research work, the students had good performance and knowledge in to sterilization/disinfection of extracted human teeth, although it seems that more education and teaching is needed for improving the quality of extracted human teeth to sterilization/disinfection.

This study showed that the students under study had a positive attitude toward sterilization of these teeth but did not have a positive attitude toward using the protective accessories such as gloves and a white cloak while handling extracted teeth. Infection control measures to protect students and faculty staff are not confined to disinfection/sterilization of extracted teeth. Instrument sterilization as well as the use of gloves, eye protection, and masks should also be considered in the preclinical laboratory.[11] Stevens reported that bacterial colonies grew on plates placed in the area of the dentists’ nose and mouth while performing dental procedures with an air turbine handpiece.[12] This study showed that students have good knowledge about disinfection of extracted teeth, although some of them did not disinfect or sterilize these teeth. Therefore, we conclude that the method in which most students use to sterilize extracted teeth is not effective in practice, and more attention should be paid to teach them a suitable method to sterilize the teeth as they are working on.

CONCLUSION

The results of this study indicated that knowledge, performance, and attitude of dental students in relation to sterilization/disinfection methods of extracted human teeth were good. However, there were shortcomings about teaching and materials suitable for sterilization.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dominici JT, Eleazer PD, Clark SJ, Staat RH, Scheetz JP. Disinfection/sterilization of extracted teeth for dental student use. J Dent Educ. 2001;65:1278–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar M, Sequeira PS, Peter S, Bhat GK. Sterilisation of extracted human teeth for educational use. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2005;23:256–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeWald JP. The use of extracted teeth for in vitro bonding studies: A review of infection control considerations. Dent Mater. 1997;13:74–81. doi: 10.1016/s0109-5641(97)80015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pantera EA, Jr, Schuster GS. Sterilization of extracted human teeth. J Dent Educ. 1990;54:283–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schulein TM. Infection control for extracted teeth in the teaching laboratory. J Dent Educ. 1994;58:411–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaffer SE, Barkmeier WW, Gwinnett AJ. Effect of disinfection/sterilization on in-vitro enamel bonding. J Dent Educ. 1985;49:658–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tate WH, White RR. Disinfection of human teeth for educational purposes. J Dent Educ. 1991;55:583–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.White RR, Hays GL. Failure of ethylene oxide to sterilize extracted human teeth. Dent Mater. 1995;11:231–3. doi: 10.1016/0109-5641(95)80054-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White JM, Goodis HE, Marshall SJ, Marshall GW. Sterilization of teeth by gamma radiation. J Dent Res. 1994;73:1560–7. doi: 10.1177/00220345940730091201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Attam K, Talwar S, Yadav S, Miglani S. Comparative analysis of the effect of autoclaving and 10% formalin storage on extracted teeth: A microleakage evaluation. J Conserv Dent. 2009;12:26–30. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.53338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berutti E, Marini R, Angeretti A. Penetration ability of different irrigants into dentinal tubules. J Endod. 1997;23:725–7. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(97)80342-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Occupational Safety and Health Administration. 29 CFR 1910.1200. Hazard communication. Fed Regist. 1994;59:17479. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Humel MM, Oliveira MT, Cavalli VG. Effect of storage and disinfection methods of extracted bovine teeth on bond strength to dentin. Braz J Oral Sci. 2007;6:1402–6. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watanabe I, Nakabayashi N. Measurement methods for adhesion to dentine: The current status in Japan. J Dent. 1994;22:67–72. doi: 10.1016/0300-5712(94)90001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Titley KC, Chernecky R, Rossouw PE, Kulkarni GV. The effect of various storage methods and media on shear-bond strengths of dental composite resin to bovine dentine. Arch Oral Biol. 1998;43:305–11. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(97)00112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.George SW, Pichardo MR, Bergeron BE, Jeansonne BG. The effect of formalin storage on the apical microleakage of obturated canals. J Endod. 2006;32:869–71. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robertson D, Leeb IJ, McKee M, Brewer E. A clearing technique for the study of root canal systems. J Endod. 1980;6:421–4. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(80)80218-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chandler NP. Preparation of dental enamel for use in intraoral cariogenicity experiments. J Dent. 1990;18:54–8. doi: 10.1016/0300-5712(90)90253-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soares LE, Brugnera A, Junior, Zanin FA, Pacheco MT, Martin AA. Effects of treatment for manipulation of teeth and Er:YAG laser irradiation on dentin: A Raman spectroscopy analysis. Photomed Laser Surg. 2007;25:50–7. doi: 10.1089/pho.2006.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pashley EL, Tao L, Pashley DH. Sterilization of human teeth: Its effect on permeability and bond strength. Am J Dent. 1993;6:189–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cuny E, Carpenter WM. Extracted teeth: Decontamination, disposal and use. J Calif Dent Assoc. 1997;25:801–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pagniano RP, Scheid RC, Rosen S, Beck FM. Airborne microorganisms collected in a preclinical dental laboratory. J Dent Educ. 1985;49:653–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parsell DE, Stewart BM, Barker JR, Nick TG, Karns L, Johnson RB. The effect of steam sterilization on the physical properties and perceived cutting characteristics of extracted teeth. J Dent Educ. 1998;62:260–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for infection control in dental health care setting. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:1–76. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Toro MJ, Lukantsova LL, Williamson M, Hinesley R, Eckert GJ, Dunipace AJ. In vitro fluoride dose-response study of sterilized enamel lesions. Caries Res. 2000;34:246–53. doi: 10.1159/000016598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robinson C, Hallsworth AS, Shore RC, Kirkham J. Effect of surface zone deproteinisation on the access of mineral ions into subsurface carious lesions of human enamel. Caries Res. 1990;24:226–30. doi: 10.1159/000261272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bitter NC. A scanning electron microscopy study of the effect of bleaching agents on enamel: A preliminary report. J Prosthet Dent. 1992;67:852–5. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(92)90600-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]