Abstract

Background:

Oral Submucous Fibrosis (OSF) is a precancerous condition of the oral mucosa. Existing treatments give only temporary symptomatic relief. Colchicine is an ancient drug with anti-fibrotic and anti-inflammatory properties. We planned to study the effects of colchicine in the management of oral submucous fibrosis.

Materials and Methods:

Fifty OSF patients were divided randomly into two groups and treated for 12 weeks. Group 1-Patients were administered tablet colchicine orally, 0.5 mg twice daily and 0.5 ml intralesional injection Hyaluronidase 1,500 IU into each buccal mucosa once a week. Group 2-Patients were administered 0.5 ml intralesional injection Hyaluronidase 1,500 IU and 0.5 ml intralesional injection Hydrocortisone acetate 25 mg/ml in each buccal mucosa once a week alternatively. Student's t test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to compare pre and post treatment results. P<0.05 was considered as significant.

Results:

Thirty-three percent in group 1 got relief from burning sensation in the second week. Inter group comparisons of increase in mouth opening and reduction in histological parameters indicated that group 1 patients responded better than group 2.

Conclusion:

These encouraging results should prompt further clinical trials with colchicine alone on a larger sample size to broaden the therapeutic usefulness of the drug in the management of OSF.

Keywords: Anti-fibrotic, anti-inflammatory, colchicine, hyaluronidase, oral submucous fibrosis

INTRODUCTION

Oral Submucous Fibrosis (OSF) is a chronic condition almost exclusively occurring among Indians and to a lesser extent in the other Asiatic people.[1] However, with the increase in immigration of people from the Indian subcontinent, dental professionals in many developed countries will encounter this disease in the near future.[2] A wide range of treatment including drug management, surgical therapy, and physiotherapy have been attempted till date, with varying degrees of benefit, but none have been able to cure this disease.[3] This is mainly due to the fact that the etiology of the disease is not fully understood and the disease is progressive in nature.[4] Instead of continuing the limited available modes of therapy, the idiopathic nature of this condition indicates new avenues for its management.[5]

Colchicine is an alkaloid found in the crocus like plant, Colchicum Autumnale, named for the land of Colchis at the eastern tip of Black Sea.[6] Chemically, it is Colchicinum-N-(5, 6, 7, 9-Tetrahydro-1, 2, 3, 10-tetramethoxy-9-oxobenzo [a] heptalen-7-yl) acetamide. Colchicine is an ancient drug-at least 2,000 years old, which is attracting renewed interest because of its actions at a subcellular level. Many studies during the past years have elucidated a variety of previously unsuspected drug actions and have demonstrated the varying effectiveness of colchicine therapy for a surprisingly broad array of diseases including recurrent aphthous stomatitis, Behcet's disease, familial Mediterranean fever, polymyositis, and scleroderma.[7] The pharmacodynamics of colchicine as an anti-fibrotic agent is well-established by various in vitro and in vivo studies [Table 1][8,9,10] warranting its use in the treatment of various diseases associated with fibrosis. The long held view that colchicine's anti-inflammatory actions are specific for gout is no longer tenable. Perhaps the most important anti-inflammatory properties of colchicine are related to the drug's effect on polymorphonuclear leukocytes and monocyte chemotaxis, leukocyte adhesiveness, the drug's action in potentiating factors that increase leukocyte cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) levels, thereby, inhibiting lysosomal degranulation that accompanies phagocytosis and its effect on the release of prostaglandin E, which suppresses the leukocyte function.[11]

Table 1.

Hence, the exciting combination of an anti-fibrotic agent along with anti-inflammatory properties of a drug that is surprisingly well tolerated, easily available, and cost effective, prompted us to embark on this study. This study was planned to compare the effectiveness of colchicine and intralesional hyaluronidase with intralesional corticosteroid and hyaluronidase in the management of OSF.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study was conducted in Government Dental College, Bangalore, between 2002 and 2004. The patients for the study were selected from those who visited our department. A formal ethical clearance to conduct this study was given by the Ethical Committee of the institute. An informed consent was obtained from the patients before including them in the study. A detailed case history of the patient with emphasis on their habits (chewing betel nut, pan parag, etc.) and a thorough clinical examination was recorded on a standard proforma. A clinical diagnosis of OSF was made based on the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria and the patients were graded clinically according to Gupta Dinesh Chandra S. et al.[12] The diagnosis was confirmed histopathologically by a punch biopsy of the lesion. Hematoxylin and Eosin and van Gieson's stains were used to analyze the staining intensity of the inflammatory infiltrate and the density of collagen fibrils, respectively, in the pre and post treatment biopsy specimens. Fifty patients (41 males and nine females) in the age group of 15 years to 55 years, thus diagnosed as having OSF, were included in the study and were divided randomly into two groups for the purpose of treatment. Group 1-Patients were administered orally tablet colchicine (Tablet Zycolchine, Zydus Cadila Healthcare Ltd., Ahmedabad, Gujrat, India) 0.5 mg twice daily. Hyaluronidase 1,500 IU was mixed in 1 ml of lignocaine. 0.5 ml of this solution was injected intralesionally in each buccal mucosa once a week. Baseline liver function tests, serum urea, and creatinine were done for these patients to rule out any existing hepatic pathology and the tests were repeated once every month during the study period and one month following cessation of treatment. Group 2-Patients were administered intralesional injection of Hyaluronidase 1,500 IU as in group 1 and 0.5 ml of injection Hydrocortisone acetate 25 mg/ml in each buccal mucosa once a week alternatively. Patients in both the groups were asked to discontinue all betel nut chewing habits during the entire study period.

Both groups were treated for 12 weeks. Post-treatment punch biopsy was taken one week after the cessation of treatment for histopathological evaluation. Patients were asked to observe for any local allergic symptoms as itching, redness or ulcerations at the site of injection or if any constitutional symptoms developed and to report the same immediately. Treatment was discontinued in such patients. During the subsequent visits the patient's response to the treatment procedures was recorded with emphasis on ascertaining the amelioration of specific symptoms like burning sensation, trismus, and intolerance to hot and spicy foods. Clinical examination of the oral mucosa, site of lesion, margins, extension, color and surface texture and presence of fibrotic bands was recorded. The interincisal opening of the mouth was recorded during each visit [Figures 1 and 2]. Pre and post treatment histopathological specimens were compared for the inflammatory cells and fibrous tissue [Figures 3a, 3b, 4a, and 4b]. Student's t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to compare pre and post treatment results. P<0.05 was considered as significant.

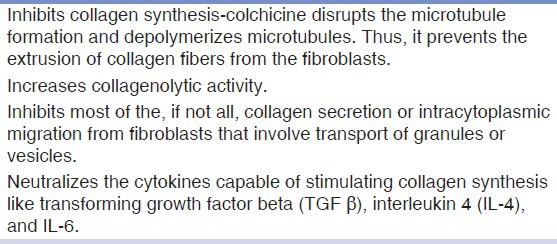

Figure 1.

Mouth opening recorded before treatment in a patient belonging to Group I

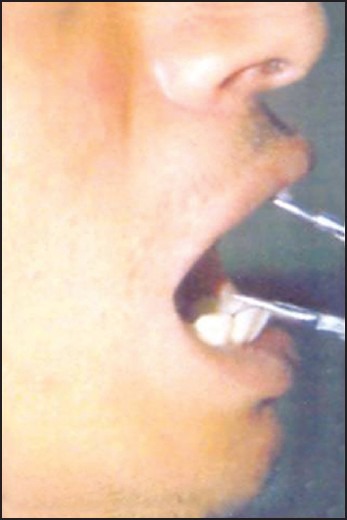

Figure 2.

Clinical improvement of mouth opening recorded in the same patient after treatment of 12 weeks

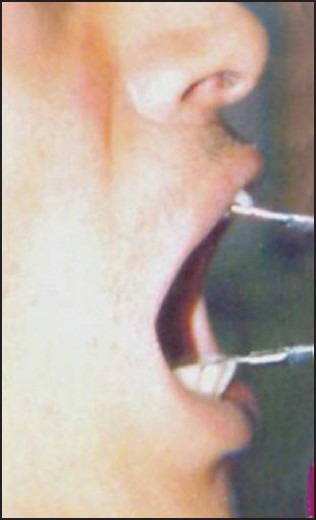

Figure 3.

(a) Photomicrograph of tissue section taken before treatment showing atrophic epithelium, relatively avascular hyalinized collagen with abundant inflammatory infiltrate (low-power view: H and E ×40), (b) Photomicrograph of the same tissue specimen stained with van Gieson's showing dense avascular hyalinized collagen (low-power view: ×40)

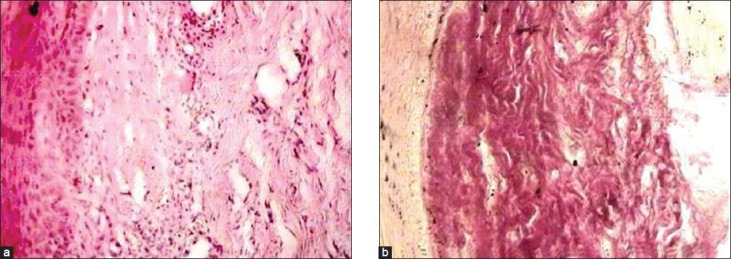

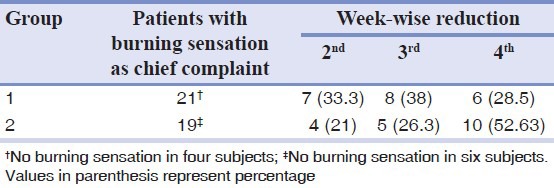

Figure 4.

(a) Photomicrograph of tissue section taken after treatment showing reduced density of collagen and inflammatory infiltrate (low-power view: H and E ×40), (b) Photomicrograph of the same tissue specimen stained with van Gieson's showing reduced density of collagen (low-power view: ×40)

RESULTS

The mean age of the patients in the study was 28.40 ± 8.6 (Mean ± SD) years, with 68 per cent in the age group of 20-29 years. Sixty-four percent of the patients complained of both trismus and burning sensation. All the patients had an areca nut chewing habit, either in the form of betel nut or other commercially available products like Pan Parag, Pan masala, Gutka etc. Additional habit of smoking was observed in only one male patient. The buccal mucosae were affected in all the patients, however, only five showed tongue involvement. The clinical grading of the patients and the inter incisal distance measured in them are shown in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

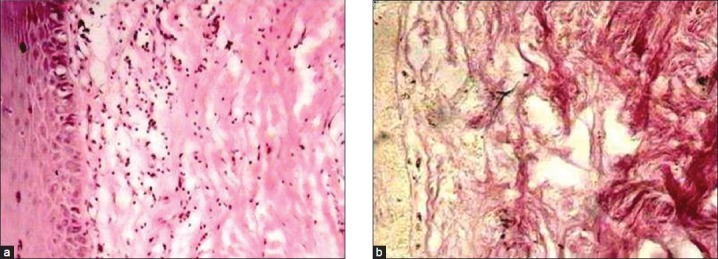

Table 2.

Distribution of the clinical grading of the patients in both the groups

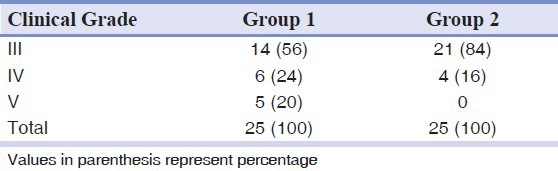

Table 3.

Distribution of inter-incisal distance measured in patients in the study groups

Almost all the patients in both the groups were relieved from burning sensation after treatment. However, 33% in group 1 got relief in the second week itself as against 21% in group 2 [Table 4]. For inter group comparison of the effectiveness of treatment in increasing the mouth opening parameters, student's t test was done that resulted in a value P < 0.05 which indicated that group 1 patients responded better than group 2. To know the effect of treatment in increasing the mouth opening parameters in the clinical grades, a test of significance, analysis of variance was carried out that resulted in P < 0.05 for grade 3 and P > 0.05 for grade 4 which indicated that clinical grade 3 responded better than grade 4. To compare the effectiveness of treatment in reducing the histological parameters in between the two groups after treatment, Student's ‘t’ test was done which resulted in a value of P < 0.05 which is statistically significant and indicated that group 1 responded better than group 2. To know the effect of treatment in reducing the histological parameters in clinical grades (3 and 4) in between two groups, a test of significance of analysis of variance (ANOVA) was done which resulted in P < 0.05 for grade 3 and P > 0.05 for grade 4 which indicates that clinical grade 3 responded better than grade 4.

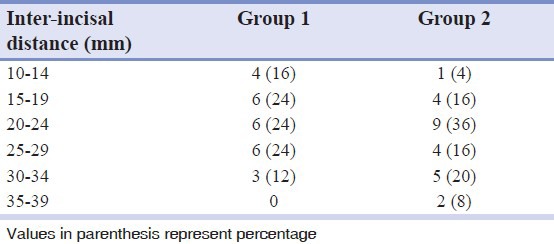

Table 4.

Week-wise reduction in burning sensation in patients of both groups after treatment

DISCUSSION

OSF is a morbid, crippling, and a premalignant condition of the oral mucosa associated with the areca nut chewing habit.[13,14] It is commonplace in various Indian states to use pan quid with tobacco and lime.[15] Several medical and surgical approaches have been tried for the management of OSF over the decades. The results are not predictable with some therapies and none has been consistently successful.[12] In 2001, Haque et al., successfully treated 29 OSF patients with recombinant interferon gamma (rhIFN-γ) and concluded that IFN-γ may reverse OSF. They tried IFN-γ in OSF based on the studies which showed that systemic recombinant IFN-γ improved the mouth opening, musculoskeletal, and pulmonary efficiency in patients with scleroderma.[16] In view of the female predilection, its presentation in middle life and histological similarities, the analogy that OSF is an “idiopathic scleroderma of mouth” seems reasonable.[17] Collagen fibrils in OSF are more embryonic in nature with a defective maturation similar to scleroderma.[18] Canniff et al., showed that OSF and scleroderma were similar with an increased frequency of HLA — DR3 and haplotypic pairs B 8/DR3 in the latter and HLA — DR3 A10 and B 7 in the former.[17] However, there is difficulty in the availability of IFN-γ and the cost of this agent is high in developing countries. Considering the shortcomings of all previous treatment modalities for OSF and the positive observations of the study by Haque et al., we have studied the effects of colchicine in the management of OSF.

The patients in group 1 showed an early reduction in the burning sensation. There was also a significant improvement in the mouth opening and in the movement of the tongue (clinical grade 5). The histopathological findings also showed a marked reduction in the inflammatory cell infiltrate and density of collagen fibrils. The mechanism by which colchicine improved the clinical status of OSF patients in our study was difficult to ascertain since the drug was used in combination with Hyaluronidase. Also since this was the first study where cochicine had been used in the treatment of OSF, we could not compare our results. However, we attributed them to the effect of colchicine which is both an anti-fibrotic and anti-inflammatory agent. Like IFN-γ, colchicine also reduces collagen synthesis, down regulates fibroblast proliferation and upregulates anti-fibrotic cytokine and collagenase synthesis in the basal layer of the epithelium and lamina propria.[16] One of our patients, however, showed relapse of the restricted mouth opening during the follow-up of 6 months after the cessation of treatment. The cause of the relapse could be due to a number of factors like the dosage being less for that particular individual or the non-compliance of treatment by the patient.

Colchicine has been reported to be beneficial in the treatment of diseases associated with fibrosis in animals and human beings.[19] The short and long term administration of colchicine therapy in moderate dosages is surprisingly well tolerated. None of our patients reported any local or systemic adverse reactions during treatment and also after the cessation of drug intake. The most common toxic side effect reported reflect the drug's action on rapidly proliferating gastrointestinal tract epithelial cells and include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. These symptoms are especially frequent at dosage levels 2-3 mg/day although they are rapidly and completely reversible.[6] It is possible that the dosage we used in our study, i.e. 0.5 mg colchicine administered orally twice a day, is an acceptable dosage, because at this dosage the patients achieved significant therapeutic results with no adverse reaction.[20] Large amounts of the drug and its metabolites enter the liver and then the bile and, hence, should not be administered to patients with hepatic disease.[21] Follow-up blood cell count should also be performed periodically and medication stopped if the toxic effects develop. Tests to determine baseline serum urea nitrogen, creatinine levels, a complete blood cell count, and liver function test, performed prior to initiating the treatment and during follow-up of our patients also recorded values within the normal range.

CONCLUSION

The encouraging results should prompt a clinical trial on more number of OSF patients to broaden the therapeutic usefulness and applications of one of our most ancient treatment agents. This baseline study gives scope for further studies with the systemic use of colchicine alone in the treatment of OSF, and, also for research in the use of the drug as a formulation that can be administered locally into the fibrous bands to confirm the above results.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pindborg JJ, Bhonsle RB, Murti PR, Gupta PC, Daftary DK, Mehta FS. Oral Submucous fibrosis as a precancerous condition. Scand J Dent Res. 1984;92:224–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1984.tb00883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aziz SR. Coming to America: Betel nut and oral submucous fibrosis. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010;141:423–8. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2010.0194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angadi PV, Rao S. Management of oral submucous fibrosis: An overview. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;14:133–42. doi: 10.1007/s10006-010-0209-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borle RM, Borle SR. Management of oral submucous fibrosis: A conservative approach. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991;49:788–91. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(91)90002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta DS, Gupta M, Oswal RH. Estimation of major immunoglobulin profile in oral submucous fibrosis by radial immunodiffusion. Int J Oral Surg. 1985;14:533–7. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9785(85)80060-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malkinson FD. Colchicine. Arch Dermatol. 1982;118:453–7. doi: 10.1001/archderm.118.7.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.29th ed. London: The Pharmaceutical Press; 1989. Martindale: The Extra Pharmacopoeia; pp. 438–9. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Segovia A, Niembro RF, Ibanez KG, Alcocer G, Tamayo P. Long term evaluation of colchicine in the treatment of scleroderma. J Rheumatol. 1979;6:705–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sapadin AN, Fleischmajer R. Treatment of Scleroderma. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:99–105. doi: 10.1001/archderm.138.1.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diegelmann RF, Peterkofsky B. Inhibition of collagen secretion from bone and cultured fibroblasts by microtubular descriptive drugs. Proc Nat Acad Sci U S A. 1972;69:892–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.4.892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wallace SI, Bernstein D, Diamond H. Diagnostic value of the colchicine therapeutic trial. JAMA. 1967;199:525–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dinesh CG, Dolas R, Ali I. Treatment modalities in oral submucous fibrosis: How they stand today? Study of 600 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992:43–7. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shah N, Sharma PP. Role of chewing and smoking habits in the etiology of oral submucous fibrosis (OSF): A case control study. J Oral Pathol Med. 1998;27:475–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1998.tb01915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeWaal J, Olivier A, van Wyk CK, Maritz JS. The fibroblast population in oral submucous fibrosis. J Oral Pathol Med. 1997;26:69–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1997.tb00024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh GP, Rizvi I, Gupta V, Bains VK. Influence of smokeless tobacco on periodontal health status in local population of north India: A cross sectional study. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2011;8:211–20. doi: 10.4103/1735-3327.86045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haque MF, Meghji S, Nazir R, Harris M. Interferon gamma (IFN-gamma) may reverse oral submucous fibrosis. J Oral Pathol Med. 2001;30:12–21. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2001.300103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pillai R, Balaram B, Reddiar KS. Pathogenesis of oral submucous fibrosis-relationship to risk factors associated with oral cancer. Cancer. 1992;69:2011–20. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920415)69:8<2011::aid-cncr2820690802>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morawetz G, Katsikeris N, Weinberg S, Listrom R. Oral submucous fibrosis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1987;16:609–14. doi: 10.1016/s0901-5027(87)80115-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guttadauria M, Diamond H, Kaplan D. Colchicine in the treatment of scleroderma. J Rheumatol. 1997;4:272–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruah B, Stram JR, Chasin WD. Treatment of severe recurrent aphthous stomatitis with colchicine. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1988;114:671–5. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1988.01860180085037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.9th ed. New York City: McGraw-Hill; 1996. Goodman and Gilman's the pharmacological basis of therapeutics; pp. 647–8. [Google Scholar]