Abstract

The TREX complex, which functions in mRNA export, is recruited to mRNA during splicing. Both the splicing machinery and the TREX complex are concentrated in 20–50 discrete foci known as nuclear speckle domains. Using a model system where CMV-DNA constructs were microinjected into HeLa cell nuclei, we have followed the fates of the transcripts. Here we show that transcripts lacking functional splice sites, which are inefficiently exported, do not associate with nuclear speckle domains but are instead distributed throughout the nucleoplasm. In contrast, pre-mRNAs containing functional splice sites accumulate in nuclear speckles, and our data suggest that splicing occurs in these domains. When the TREX components UAP56 or Aly are knocked down, spliced mRNA, as well as total polyA+ RNA, accumulates in nuclear speckle domains. Together, our data raise the possibility that pre-mRNA undergoes splicing in nuclear speckle domains, before release by TREX components for efficient export to the cytoplasm.

Introduction

Biochemical studies have revealed that the machineries for transcription, RNA processing, and mRNA export are extensively coupled to one another via a complex network of both physical and functional interactions1–4. Coupling among the steps of gene expression is also apparent at the cellular level4–6. For example, in yeast, defects in either the factors or steps in mRNA processing typically result in accumulation of transcripts at the site of transcription where they are ultimately degraded7–10. Likewise, yeast transcripts are retained and degraded at the site of transcription in mRNA export mutants10. Although less is understood in human cells, several studies have raised the possibility that the coupled steps in gene expression take place within or near nuclear compartments variously known as nuclear speckle domains, splicing factor compartments, interchromatin granules (IGCs), or SC35 domains4, 5. The earliest reports came from fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis of RNA transcripts from highly expressed endogenous genes5 (and references therein). These studies indicated that, for many genes, transcription occurs in the vicinity of nuclear speckle domains and that mRNA processing occurs near or within the domains11–15. Additional work supported the view that nuclear speckle domains are sites of RNA processing, as evidence indicates that pre-mRNAs can undergo spliceosome assembly and splicing within nuclear speckle domains5, 16–20. Recent studies have lent additional support to the view that nuclear speckle domains play an important role in the expression of actively transcribed genes4, 6. In particular, an active allele or co-expressed genes cluster together around, or associate with, nuclear speckle domains21–23. For example, co-transcribed erythroid genes located on four different chromosomes cluster together around a common nuclear speckle domain21. Other studies of nuclear speckle domains indicate that they function as storage and recycling sites for the RNA processing machinery, and for some genes, the processing machinery moves from these domains to the transcriptionally active genes24–28. Additional work has also led to the view that nuclear speckle domains are sites where over-expressed exogeonous pol II transcripts and/or aberrant RNAs (such as cDNA transcripts) accumulate26, 27. However, other studies are not consistent with this view, as cDNA transcripts were not detected in nuclear speckle domains18–20. Thus, further work is needed to understand how nuclear speckle domains function in the pathway of gene expression.

Nuclear speckle domains are not only sites enriched in RNA processing machineries but also contain the mRNA export machinery (e.g. the TREX complex) and mRNA surveillance machinery (e.g. EJC (exon junction complex)5, 28–30. The conserved TREX complex contains the multi-subunit THO complex and UAP56, Aly, Tex1, and CIP2931–36 (Dufu et al. manuscript submitted). In humans, efficient recruitment of the TREX complex to mRNA is splicing-dependent, consistent with the observation that the TREX complex co-localizes with splicing factors in nuclear speckle domains31, 32. Specifically, we previously found that the TREX complex is more efficiently recruited to mRNAs generated by splicing than to cDNA transcripts37–40. This increased recruitment correlated with increased export efficiency of spliced mRNAs relative to cDNA transcripts41. During this analysis41, we observed that the transcripts containing introns were present in discrete nuclear foci in HeLa cells, but this observation was not further investigated. In this study, we have used a nuclear microinjection assay to determine the fates of transcripts encoded by CMV-DNA constructs either containing or lacking functional splice sites. We show that both types of transcripts are detected at similar levels in the nucleus. However, cDNA transcripts and three different random-sequence transcripts do not associate with nuclear speckle domains, whereas transcripts containing functional splice sites do. Using splicing-specific FISH probes, our data suggest that splicing occurs in nuclear speckle domains. Finally, we show that a spliced reporter mRNA, as well as total polyA+ RNA, accumulates in nuclear speckle domains when TREX components UAP56 or Aly are knocked down. Together, these data indicate that transcripts containing functional splice sites associate with nuclear speckle domains, undergo splicing within these domains, and TREX components UAP56 and Aly function in releasing the mRNA from the domains for export to the cytoplasm. How these data relate to expression of endogenous genes is discussed.

Results

Splicing-dependent association of RNA with nuclear speckles

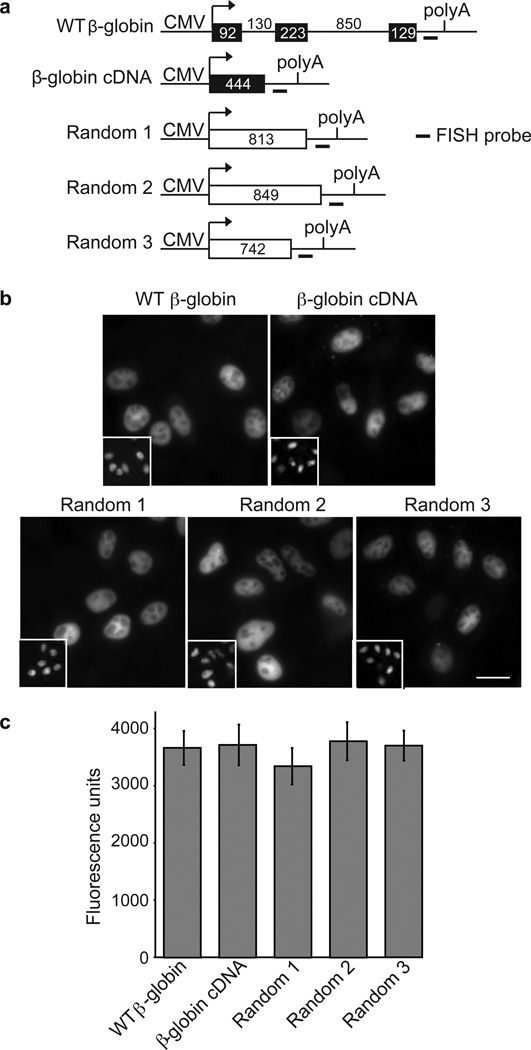

We previously showed that spliced mRNAs are exported more efficiently than their corresponding cDNA transcript counterparts in both Xenopus oocytes and HeLa cells41, 42. To further investigate the role of splicing in mRNA export, we microinjected a variety of DNA constructs containing a CMV promoter and the BGH polyadenylation site into HeLa cell nuclei and then examined the nucleoctyoplasmic distribution of the transcripts using FISH. Initially, we compared a wild type (WT) CMV-β-globin DNA construct containing its natural introns, a CMV-β-globin cDNA, and three CMV-DNA constructs encoding random sequences lacking functional splice sites (Fig. 1a). Each of these constructs was microinjected into nuclei, cells were fixed after 5 mins of incubation, followed by FISH (Fig. 1b; inset panels show the dextran nuclear injection marker). This analysis revealed that all of the CMV-constructs were transcribed and that the nascent transcripts were detected in the nucleus. Quantitation of FISH images for a minimum of 40 individual cells per construct revealed that the total amount of RNA detected was similar for all five constructs (Fig. 1c). Consistent with previous results41, by six hrs after microinjection, spliced WT β-globin mRNA was largely detected in the cytoplasm whereas the cDNA transcript and three random sequence-transcripts were largely detected in the nucleus (Supplementary Figure S1). We conclude that both spliced and cDNA/random sequence RNAs are present at similar levels, and only the spliced mRNA accumulates to high levels in the cytoplasm.

Figure 1. FISH of RNAs after transcription of CMV-DNA constructs.

(a) Schematic of constructs. The CMV promoter and BGH polyA sites and the location of the FISH probe (indicated by short line) are shown. The sizes (in nts) of the introns, exons, cDNA and random transcripts are indicated for the respective constructs. (b) FISH of indicated transcripts detected 5 mins after microinjection of CMV-DNA constructs (50 ng/µl) into HeLa cell nuclei. FITC-conjugated dextran was co-injected as a nuclear marker (inset panels). Scale bar, 10 µm. (c) Quantification of total FISH fluorescence was determined for a minimum of 40 cells for each construct. Data represent the average of three experiments, and error bars indicate standard error.

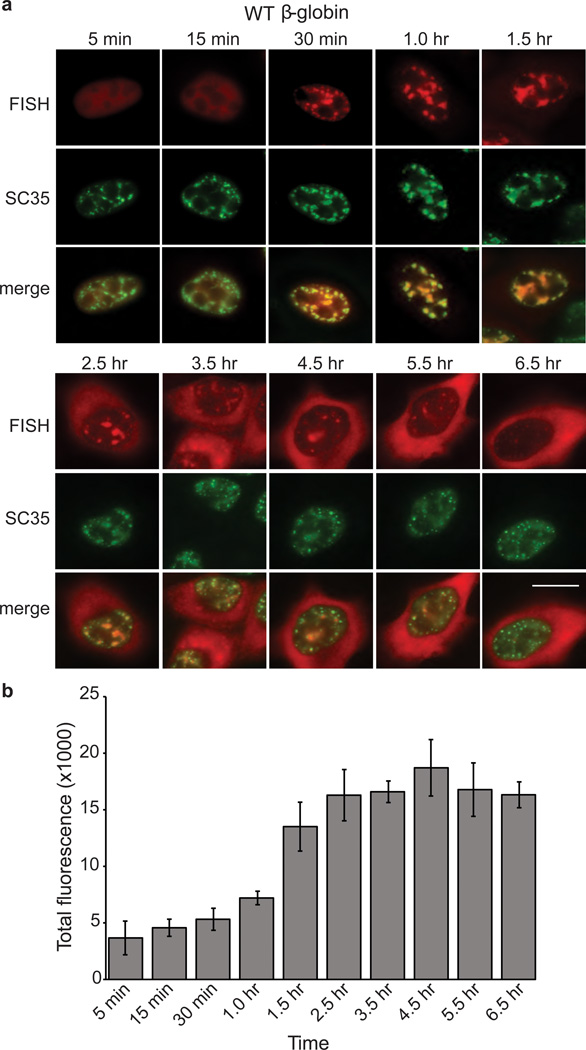

To further investigate the distribution of WT β-globin transcripts, we microinjected the CMV-β-globin DNA construct,α-amanitin was added 30 mins after microinjection, and then a time course was carried out using FISH. A representative cell for each time point is shown in Fig. 2a, and fields of cells are shown in Supplementary Figure S2. As indicated by quantitation of the FISH signal (Fig. 2b), transcripts continued to accumulate for up to 1.5 hrs, most likely due the time required for the α-amanatin to inhibit further transcription. Examination of the WT β-globin FISH signal at the 5 and 15 min time points revealed that the transcripts were evenly distributed throughout the nucleoplasm (Fig. 2a, FISH panels). By 30 mins, the transcripts began to concentrate as multiple nuclear foci and continued to be detected in these foci for up to 1.5 hrs (Fig. 2a, FISH panels). Thereafter, the transcripts were also detected in the cytoplasm where they continued to accumulate over time (Fig. 2a, FISH panels). As shown in Fig. 2a (SC35 and merge panels), the nuclear foci containing the β-globin transcripts co-localize by immunofluorescence (IF) with the splicing factor SC35, the standard marker for nuclear speckle domains4, 5, 28. As our FISH assay detects RNA transcripts as a population, and previous work has shown that RNA and the contents of nuclear speckle domains move dynamically between the domains and the nuceloplasm43, our study does not distinguish between the (long debated) possibilities that nascent transcripts enter pre-existing nuclear speckle domains or whether factors exit the domains and associate with nascent transcripts to form speckles. A great deal of elegant work has dealt with these issues and also with the detailed morphology of nuclear speckle domains and sub-domains within nuclear speckle domains5, 44 (and refs therein). In addition, previous work17 and our study show that nuclear speckle domains often appear enlarged and/or coalesced, possibly because of the large amount of RNA associated with the domains under certain conditions. Our study is not focused on these detailed aspects of nuclear speckle domain formation, dynamics, and morphology, and thus, with these caveats in mind, for simplicity, we will refer to transcripts as being in nuclear speckle domains throughout this manuscript.

Figure 2. Wild type β-globin transcripts associate with nuclear speckle domains.

(a) FISH time course showing nucleocytoplasmic distribution of β-globin transcripts after microinjection of wild type (WT) β-globin DNA construct into HeLa cell nuclei. α- amanitin was added at the 30 min time point to block further transcription. Cells were incubated for the indicated times before fixation. FISH, IF using an SC35 monoclonal antibody, and merged images are indicated. Scale bar, 10 µm. (b) Quantification of total FISH fluorescence was determined for a minimum of 10 cells for each time point. Data represent the average of three experiments, and error bars indicate standard error.

Importantly, quantitation of the total FISH signals during our time course (Fig. 2b) revealed that the β-globin transcripts remain at about the same levels starting at 1.5 hrs through 6.5 hrs. Over this time period, transcripts are detected in nuclear speckle domains and then detected in the cytoplasm. As the levels of transcripts were roughly the same over this time period, these data indicate that most of the RNA associated with the nuclear speckle domains is exported to the cytoplasm. Together, our data indicate that β-globin transcripts are first present throughout the nucleoplasm at the earliest times after transcription, followed by association with nuclear speckle domains, and then rapid export to the cytoplasm without an intermediate site of accumulation. Thus, transcript release from nuclear speckle domains appears to be a rate-limiting step in export of at least this spliced mRNA reporter.

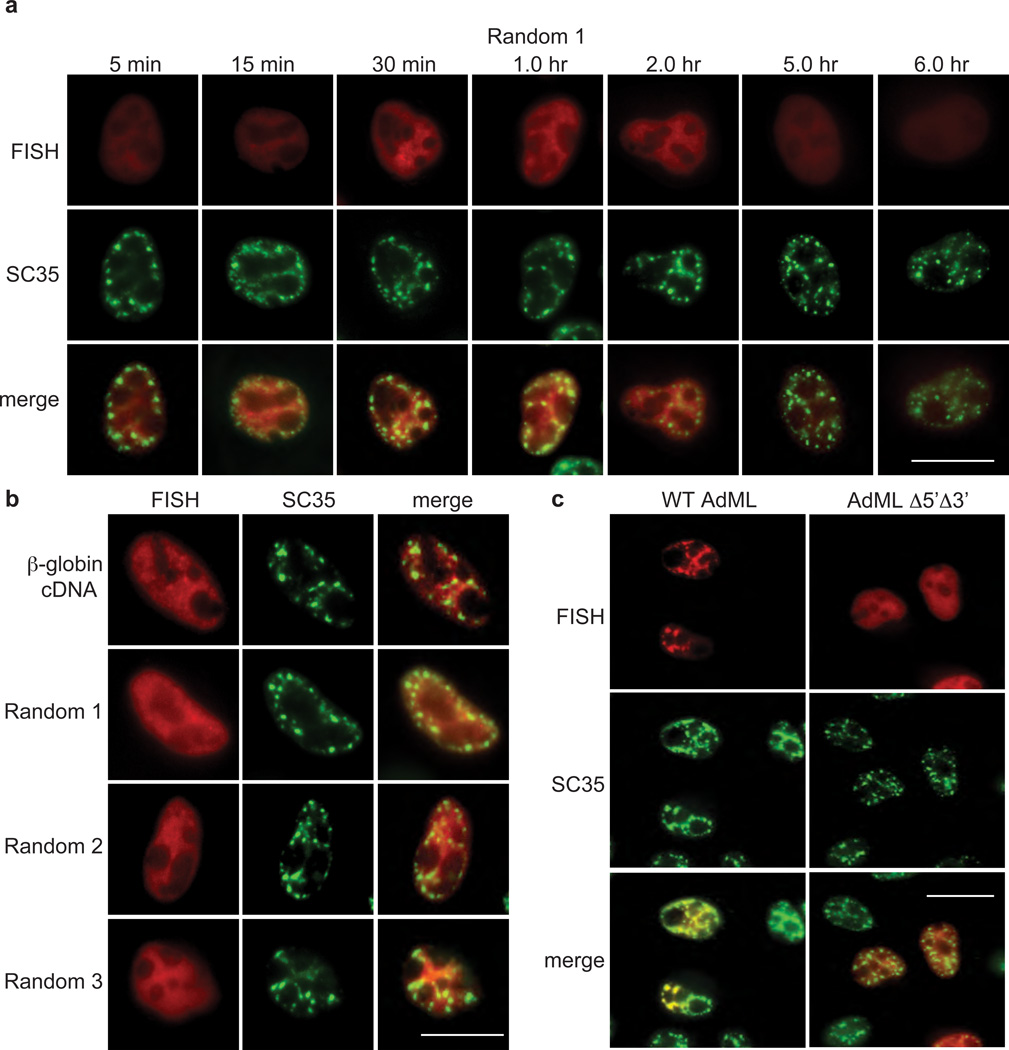

To further investigate the significance of the speckle association of WT β-globin transcripts (Fig. 2), we microinjected three CMV-DNA constructs encoding random sequences and a construct encoding CMV-β-globin cDNA into HeLa cell nuclei, followed by addition of α-amanitin at 30 mins (Fig. 3a, b). FISH analysis at the earliest time point after microinjection (5 mins, Fig. 3a) revealed that Random 1 transcripts were evenly distributed throughout the nucleoplasm, as observed with WT β-globin transcripts (Fig. 2a). However, in contrast to WT β-globin transcripts, Random 1 transcripts remained evenly distributed in the nucleoplasm throughout the time course (Fig. 3a, FISH panels). Moreover, co-localization studies with SC35 revealed that Random 1 transcripts do not associate with nuclear speckle domains (Fig. 3a, SC35 and merge panels). A FISH comparison at the 1-hr time point for all three Random transcripts and the β-globin cDNA transcript revealed that none of these transcripts co-localized with SC35 (Fig. 3b). Consistent with these data, a FISH time course carried out for Random 2 and 3 transcripts confirmed that they do not associate with nuclear speckle domains at any time point (Supplementary Figure S3). Finally, when another wild type CMV-DNA construct, AdML, or a splice-defective counterpart containing mutated 5’ and 3’ splice sites (CMV-AdMLΔ5’Δ3’), was microinjected into HeLa cell nuclei, the WT AdML transcript was distributed in discrete nuclear foci, which co-localized with SC35 (Fig. 3c, SC35 and merge) whereas the AdMLΔ5’Δ3’ transcript was diffusely distributed in the nucleoplasm (Fig. 3c, SC35 and merge). Together, the data with all of our constructs indicate that association of transcripts with nuclear speckle domains requires functional splice sites.

Figure 3. Splice-site dependent association of transcripts with nuclear speckle domains.

(a) CMV Random 1-DNA construct was microinjected in HeLa nuclei, and α-amanitin was added after 30 mins to block further transcription. A FISH time course for Random 1 RNA was carried out at the indicated times. FISH, IF using an SC35 monoclonal antibody, and merged images are shown. Scale bar, 10 µm. (b) same as (a) except Random 1, 2, and 3 CMV-DNA constructs and CMV β-globin cDNA-construct were microinjected, and FISH was carried out 1 hr after microinjection. (c) same as (a) except CMV-WT AdML or CMV-Δ5’ Δ3’ AdML DNA constructs were used, and FISH was carried out 30 mins after microinjection. FISH, IF using an SC35 monoclonal antibody, and merged images are shown. Scale bar, 10 µm.

We also investigated the nuclear localization of the microinjected CMV-DNA constructs and found that they associated with nuclear speckle domains in a splice-site dependent manner (Supplementary Figure S4). The CMV-DNA constructs most likely move by free diffusion. The splice-site dependent association with nuclear speckle domains may occur because nascent transcripts with functional splice sites are still attached to the DNA. Further studies are needed to determine whether these observations with the CMV constructs are related to studies showing that actively transcribed endogenous genes associate with nuclear speckles domains4, 5, 21.

Evidence that splicing occurs in nuclear speckle domains

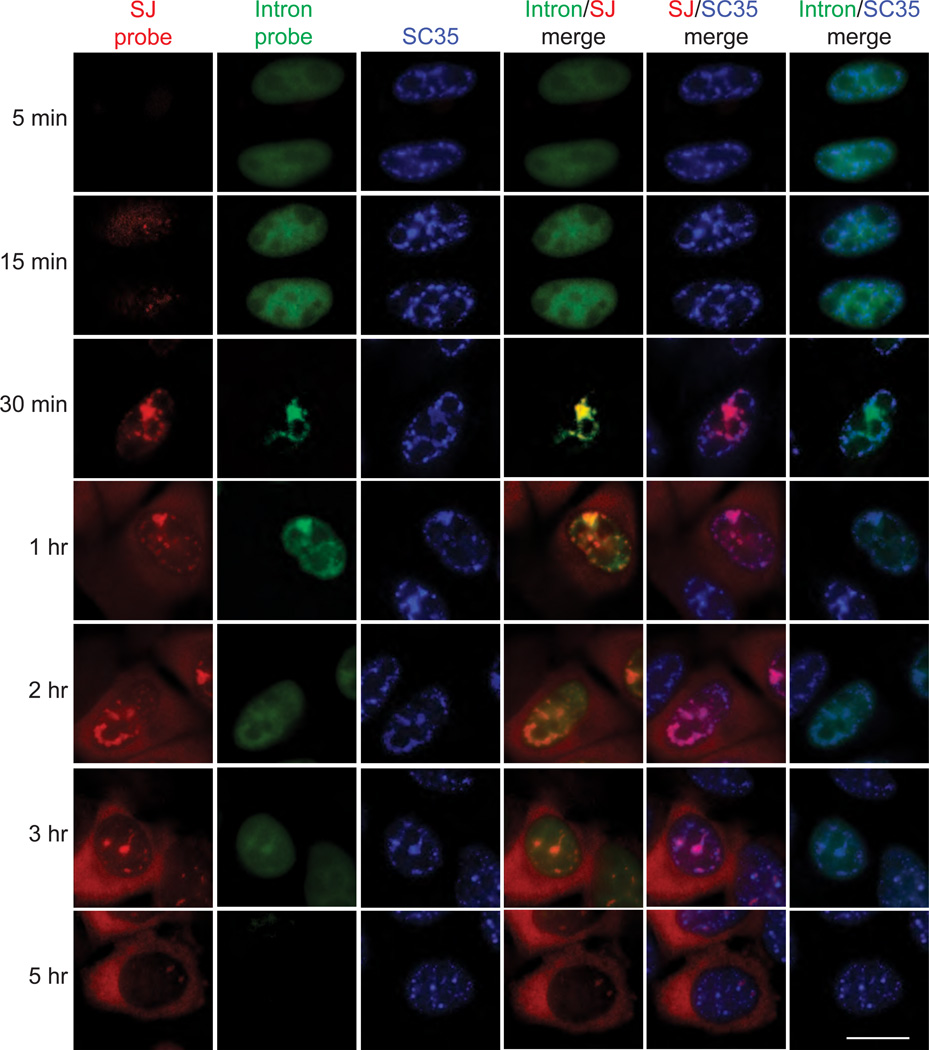

We next investigated whether splicing of the CMV-transcripts occurs in nuclear speckle domains. Initially, we carried out RT-PCR to obtain a general idea about the splicing kinetics of the total β-globin RNA population after microinjection of the CMV-DNA construct. Mostly unspliced pre-mRNA was present at early times (5 and 15 mins) after microinjection and mostly spliced mRNA at later time points (30 and 60 mins) (Supplementary Figure S5). We next carried out a FISH time course using a probe to the exon 2-exon 3 splice junction (SJ probe) to detect only spliced mRNA or a probe specific to intron 2 (intron probe, which detects both the unspliced pre-mRNA and the intron) (Fig. 4). By 5 and 15 mins after microinjection, β-globin RNA was detected throughout the nucleoplasm, and only with the intron probe (Fig. 4), consistent with the presence of unspliced pre-mRNA at early times. By 30 mins, the RNA was detected with both the splice junction and intron probes, consistent with the presence of spliced mRNA at this time point. Of particular significance, the transcripts detected with the splice junction and intron probes were well co-localized with each other, but were present in only a subset of nuclear speckle domains (Fig. 4, 30 mins, compare SJ and intron probe panels and merge, and compare SJ/SC35 merge and intron/SC35 merge). The observation that the same subset of nuclear speckle domains was detected with both the intron and the splice junction probes suggests that splicing occurs within the nuclear speckle domains. If, for example, the RNA were moving rapidly between different speckles, then we would expect to detect different speckles with the intron versus the splice junction probe.

Figure 4. FISH time course ofβ-globin transcripts using splice junction- or intron-specific probes.

(a) CMV β-globin-DNA construct was microinjected into nuclei, α-amanitin was added at 30 mins, and FISH was carried out at the indicated times. Probes were to the second splice junction (SJ probe) or the second intron (intron probe) of β-globin mRNA. IF was carried out using an SC35 monoclonal antibody. The indicated merged FISH and IF images are shown. Scale bar, 10 µm.

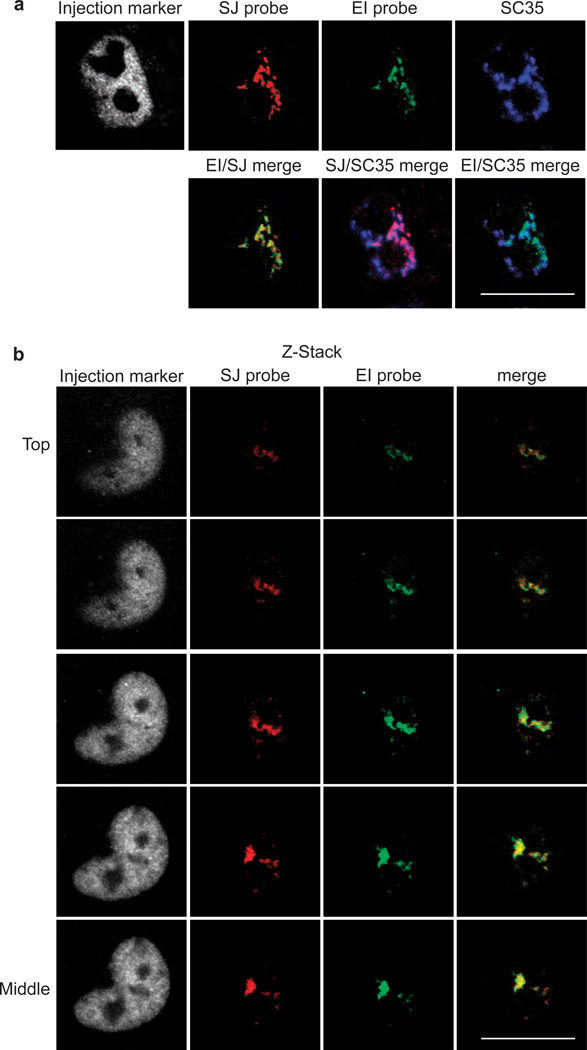

To further investigate the possibility that splicing takes place within nuclear speckle domains, we carried out confocal microscopy using the splice junction probe as well as a probe to the exon-intron junction (EI probe, which detects unspliced pre-mRNA, Fig. 5a). At the 30-minute time point, the confocal data show that the transcripts detected with both the splice junction and exon-intron junction probes co-localize with each other and also with SC35. Moreover, the data show that the transcripts are localized in only a subset of the nuclear speckle domains. Z-stack confocal images further show the co-localization of transcripts detected with the splice junction and exon-intron junction probes (Fig. 5b). Together, these data suggest that splicing of β-globin pre-mRNA occurs within nuclear speckle domains.

Figure 5. Evidence thatβ-globin pre-mRNA is spliced in a subset of nuclear speckle domains.

(a) CMV-β-globin DNA was microinjected into nuclei, and FISH was carried out after 30 mins using a probe to the splice junction (SJ probe) or the intron-exon junction (IE probe). IF with SC35 monoclonal antibody was carried out after the FISH. Confocal microscopy was used to visualize the cells. The nucleus was detected by the injection marker. The indicated merged images are shown in the second row. (b) Z-Stacked confocal images for a representative nucleus using the indicated probes or SC35 antibody for IF are indicated. Z-stacks were taken in steps of µm. The Top to Middle sections of the Z-stacks are shown. Scale bar, 10 µm.

UAP56 functions in release of mRNA from nuclear speckles

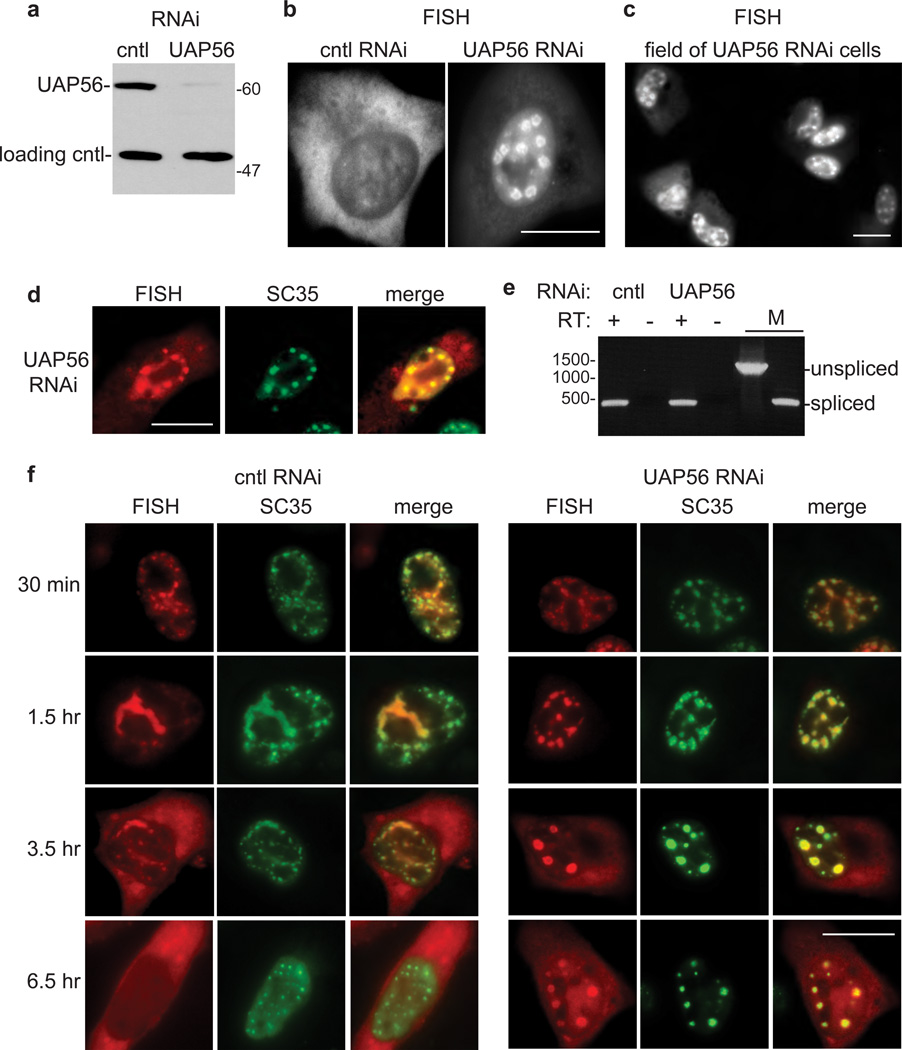

As the TREX export machinery localizes in nuclear speckle domains and associates with mRNAs during splicing, we next investigated the link between TREX, mRNA export, and nuclear speckle domains. Previous studies showed that UAP56 knockdown results in strong nuclear retention of mRNA with accumulation in distinct nuclear foci45, 46, but the identity these foci was not investigated. To characterize the foci, we carried out RNAi of UAP56 in HeLa cells, using non-targeting siRNAs as a negative control. As shown by Western analysis, UAP56 protein levels were efficiently knocked down (Fig. 6a). To determine the effects of the knockdown on the nucleocytoplasmic distribution of RNA, we microinjected the WT CMV-β-globin DNA construct (Fig. 1a) into HeLa cell nuclei, allowed transcription for 30 mins, added α-amanitin to block further transcription, and then used FISH to detect β-globin RNA after 3.5 hrs (Fig. 6b). In the negative control knockdown, β-globin RNA was detected mainly in the cytoplasm (Fig. 6b, cntl RNAi). In marked contrast, in the UAP56 knockdown, β-globin RNA was detected in discrete nuclear foci (Fig. 6b, UAP56 RNAi; a field of microinjected cells at lower magnification is shown in Fig. 6c). As shown in Fig. 6d, the β-globin RNA detected by FISH co-localized with SC35. Thus, UAP56 knockdown results in a strong accumulation of β-globin RNA in nuclear speckle domains. As immunodepletion of UAP56 from nuclear extracts results in inhibition of splicing in vitro47, 48, and splicing-defective transcripts that are capable of at least partial spliceosome assembly accumulate in nuclear speckle domains5, 16 (and refs therein), we asked whether UAP56 knockdown affected splicing of the β-globin reporter in vivo. As shown in Fig. 6e, RT-PCR revealed only spliced mRNA in both the UAP56 knockdown and negative control knockdown cells. These data indicate that a splicing defect does not account for the accumulation of β-globin mRNA in nuclear speckle domains in the UAP56 knockdown cells.

Figure 6. β-globin mRNA accumulates in nuclear speckle domains in UAP56 knockdown cells.

(a) Western analysis using whole cell lysates from control (cntl) or UAP56 knockdown cells probed with an antibody against UAP56 or an antibody against tubulin as a loading control. Molecular weight markers in kilodaltons are shown. (b) CMV-β-globin DNA construct was microinjected into the nuclei of control knockdown or UAP56 knockdown cells followed by FISH for β-globin mRNA. Scale bar, 10µm. (c) Same as (b), but shown at lower magnification. Scale bar, 10µm. (d) FISH for β-globin mRNA in UAP56 knockdown cells 3.5 hr after microinjection, SC35 IF using an SC35 monoclonal antibody, and merged FISH and IF images are shown. Scale bar, 10µm. (e) RT-PCR of total RNA extracted from control knockdown and UAP56 knockdown cells microinjected with β-globin DNA. RT (reverse transcriptase): + and − indicates reactions carried out in the presence or absence of RT, followed by PCR. DNA size markers (in base pairs) are indicated on the left. M: marker for unspliced and spliced mRNAs. (f) FISH time course showing nucleocytoplasmic distribution of β-globin transcripts after microinjection of wild type (WT) β-globin DNA construct into the nuclei of control knockdown or UAP56 knockdown cells. α-amanitin was added at the 30 min time point to block further transcription. Cells were incubated for the indicated times before fixation. FISH, IF using an SC35 monoclonal antibody, and merged FISH and IF images are shown. Scale bar, 10 µm.

To further examine the role of UAP56 in the accumulation of mRNA in nuclear speckle domains, we microinjected the CMV-β-globin DNA construct into UAP56 or control knockdown cells and then carried out a time course. At 30 min after microinjection, the accumulation of β-globin transcripts in nuclear speckle domains appeared similar in the UAP56 and control knockdown cells (Fig. 6f, 30 min). However, at the subsequent time points, the nuclear speckle domains appeared rounded in the UAP56 knockdown cells compared to the control cells (Fig. 6f). This round phenotype likely results from the high levels of transcripts that accumulate in nuclear speckle domains in the UAP56 knockdown cells; these transcripts are able to exit the domains in the control knockdown (or normal) cells. The time course also shows that some of the β-globin mRNA reaches the cytoplasm by the 3.5 and 6.5 hr time points in the UAP56 knockdown cells (Fig. 6f). This may occur because sufficient UAP56 remains after knockdown to allow slow release from nuclear speckle domains (i.e. a leaky phenotype) or because UAP56 knockdown only delays release of mRNA from the domains. At present, we cannot distinguish between these and other possibilities.

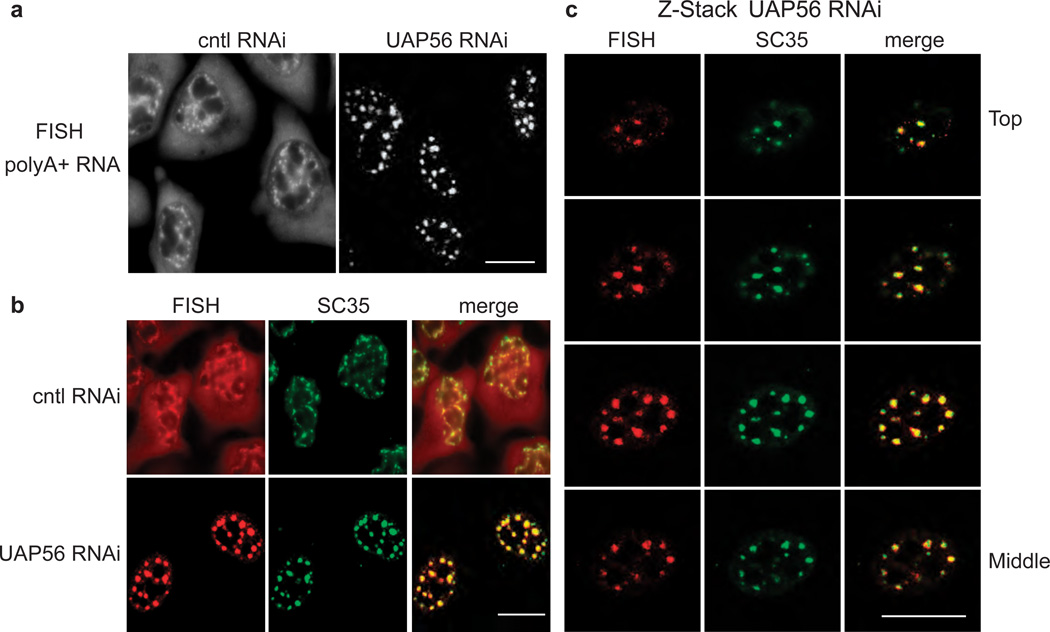

To ascertain whether UAP56-dependent release of spliced mRNAs from nuclear speckle domains occurs with endogenous mRNAs, we next examined the distribution of total polyA+ RNA in UAP56 knockdown cells. The expected distribution of polyA+ RNA was observed in negative control knockdown cells (Fig. 7a, cntl RNAi), in which the RNA is present in both the nucleus and cytoplasm49–51. In the nucleus, a portion of the steady state polyA+ RNA is present in nuclear speckle domains15, 16, 52, 53. In marked contrast to the non-knockdown cells, in the UAP56 knockdown cells, polyA+ RNA was only present in the nucleus, where it strongly accumulated in multiple foci (Fig. 7a, UAP56 RNAi). As shown in Fig. 7b, the polyA+ RNA in UAP56 knockdown cells co-localized with SC35, indicating that these foci correspond to nuclear speckle domains. Z-stack images from confocal microscopy confirm the co-localization of polyA+ RNA in UAP56 knockdown cells with nuclear speckle domains (Fig. 7c). We conclude that UAP56 knockdown results in accumulation of polyA+ RNA in nuclear speckle domains. We did not detect any splicing defects in UAP56 knockdown cells when we assayed two endogenous mRNAs (DNAJB1 and BRD2, data not shown)54. Thus, as observed with β-globin mRNA, our data indicate that splicing inhibition is not likely to account for the accumulation of polyA+ RNA in nuclear speckle domains in UAP56 knockdown cells, though we cannot rule out the possibility that UAP56 knockdown inhibits splicing of a subset of pre-mRNAs.

Figure 7. PolyA+ RNA accumulates in nuclear speckle domains in UAP56 knockdown cells.

(a) FISH of polyA+ RNA in control and UAP56 knockdown cells. Scale bar, 10µm. (b) FISH for polyA+ RNA followed by IF using an SC35 monoclonal antibody in control or UAP56 knockdown cells. The merged FISH and IF images are shown in the right panel. Scale bar, 10 µm. (c) Z-Stack confocal analysis of FISH for polyA+ RNA, SC35 IF, and merged images are indicated. Z-stacks were taken in steps of µm. The Top to Middle sections of the Z-stacks is shown. Scale bar, 10 µm.

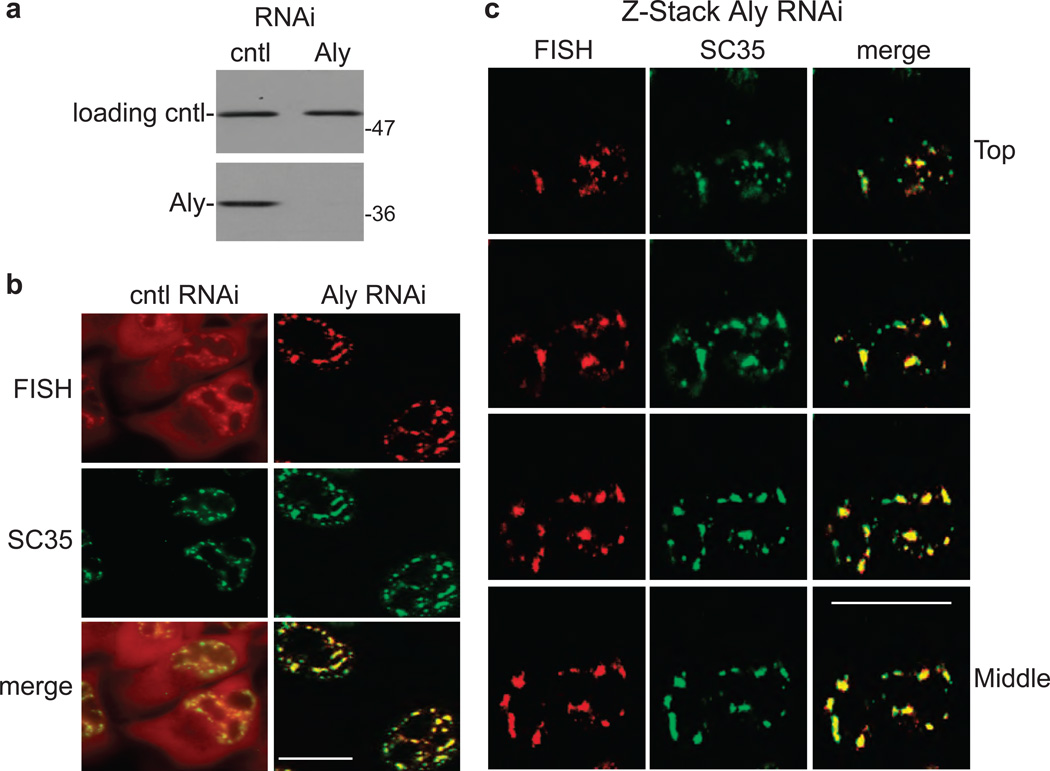

Aly functions in release of mRNA from nuclear speckles

To determine whether other TREX components play a role in release of mRNA from nuclear speckle domains, we knocked down Aly (Fig. 8a). Consistent with previous studies55, 56, Aly knockdown inhibits mRNA export (Fig. 8b). Significantly, our data show that total polyA+ RNA is retained in nuclear speckle domains after Aly knockdown (Fig. 8b). Z-stack images from confocal microscopy confirm the co-localization of polyA+ RNA in Aly knockdown cells with nuclear speckle domains (Fig. 8c). Together, these data indicate that at least two TREX components, UAP56 and Aly, function in release of mRNA from nuclear speckle domains.

Figure 8. PolyA+ RNA accumulates in nuclear speckle domains in Aly knockdown cells.

(a) Western analysis using whole cell lysates from control (cntl) or Aly knockdown cells probed with an antibody against Aly or against tubulin as a loading control. Molecular weight markers in kilodaltons are shown. (b) FISH for polyA+ RNA followed by IF using an SC35 monoclonal antibody in control or Aly knockdown cells. The merged FISH and IF images are shown in the bottom panels. Scale bar, 10 µm. (c) Z-Stack confocal analysis of FISH for polyA+ RNA, SC35 IF, and merged images are indicated. Z-stacks were taken in steps of µm. The Top to Middle sections of the Z-stacks are shown. Scale bar, 10 µm

Discussion

Nuclear speckle domains are 25–50 discrete foci that contain the machineries for pre-mRNA processing and mRNA export (the TREX complex), as well as polyA+ RNA. Here, we analyzed total polyA+ RNA and also microinjected CMV-DNA constructs into HeLa cell nuclei to investigate the relationships between pre-mRNA splicing, mRNA export, and nuclear speckle domains. Our study led to three main conclusions. 1. Only pre-mRNAs containing functional splice sites localize to nuclear speckle domains. 2. Spliced mRNA accumulates within the domains. 3. The TREX components UAP56 and Aly function in releasing spliced mRNA/polyA+ RNA from the domains for export to the cytoplasm.

As our work employed CMV-DNA constructs, which are introduced exogenously into nuclei and are also highly expressed, a key issue is how these data relate to expression of endogenous genes. An important point in this regard is that knockdown of TREX components resulted in the accumulation of not only the exogenous reporter mRNA, but also endogenous polyA+ RNA, in nuclear speckle domains. In contrast, we did not observe an increase in levels of polyA+ RNA in the surrounding nucleoplasm. Thus, these data raise the possibility that a significant fraction of the endogenous mRNA in the nucleus passes through nuclear speckle domains prior to export to the cytoplasm. As our data and previous work18, 19 indicate that association of transcripts with nuclear speckle domains is splicing-dependent, the data argue that this fraction of endogenous mRNAs were spliced in nuclear speckle domains and then exported. Our study also shows that transcripts such as cDNAs or random-sequence RNAs do not associate with speckles, and these RNAs are poorly exported. Thus, putting all of the data together, it is possible that a pre-requisite for efficient export of many mRNAs is that pre-mRNAs enter nuclear speckle domains, undergo splicing, followed by TREX-dependent release and efficient export. Previous work has shown that splicing-defective introns that are either capable of forming partial spliceosomes or are part of multi-intron pre-mRNAs are retained in nuclear speckle domains16. Thus, these data indicate that nuclear speckle domains may function as quality control centers once these defective mRNAs are present in the domains5, 16. Properly processed mRNAs that pass this quality control checkpoint are rapidly and efficiently exported.

Recent studies showing that an active allele23, a set of hormone-regulated genes22, or a set of regulated erythroid genes21 all associate with nuclear speckle domains supports the view that these domains are specific sites for orchestrating nuclear events in expression of at least a subset of genes5, 16. In light of these studies on specific endogenous genes and our results, it will be interesting to determine the generality of nuclear speckle domain function in splicing and TREX-dependent release for export of endogenous pre-mRNAs. This analysis is especially relevant to previous studies indicating that splicing of at least some endogenous pre-mRNAs occurs at the site of transcription, and not within speckles16, 57. Further work is needed to determine how these pre-mRNAs are targeted for export and why they do not increase in levels in the nucleoplasm when TREX components are knocked down. Although our data indicate that a key function for UAP56 and Aly, and possibly the entire TREX complex, in releasing spliced mRNA from nuclear speckle domains, further studies are needed to understand the mechanisms involved in this release as well as other important roles the TREX machinery may play during the mRNA export pathway.

Methods

Plasmids, Primers, and Antibodies

The plasmids encoding wild type human β-globin pre-mRNA and cDNA were constructed by adding a 5′ Myc tag and a 3′ HA tag to both intron-containing and intron-lacking β-globin by PCR amplification using the forward primer 5'CGGGGTACCGCCGCCACCATGGAACAAAAACTCATCTCAGAAGAGGATCTG CCATGGGTGCATCTGACTCCT 3' and the reverse primer 5' CGCAGAGATATCTTAAGCGTAGTCTGGGACGTCGTATGGGTACGTAGCGTGA TACTTGTGGGC. PCR products were cloned into KpnI and EcoRV sites in pcDNA3. The plasmids encoding CMV wild type AdML and CMV A5’A3’AdML were constructed by inserting a PCR fragment containing AdML60 and A5’A3’AdML60 into the Kpn1 and Xba1 sites in pcDNA3.1. In the Δ5’Δ3’AdML60, the wild type 5’ splice-site sequence (GTTGGGGTGAG) was replaced with (ATTGGAGCCAC), and for the 3’ splice site mutation, 8 consecutive T residues (nts 155–162 in AdML) were replaced with GTGATCAC. The plasmid encoding Random 1 was constructed by using PCR to amplify a fragment from total genomic HeLa DNA containing the anti-sense sequence of human α-interferon (IFNA1). The forward primer was 5’ACTAAGCTTAGAACCTAGAGCCCAAGGTT 3’ and the reverse primer was 5’ ACTAAGCTTACACTAACCACAGTGTAAAGGT 3’. The PCR product was inserted into the HindIII site of pcDNA3. The plasmid encoding Random 2 was constructed by first inserting a PCR fragment containing the sense sequence of human β-interferon (IFNB1) generated using the forward primer 5’ACTGCTAGCACATTCTAACTGCAACCTTTCG 3’ and the reverse primer 5’ ACTCTTAAGCACAGCAGTTCATGCCAT 3’ into the Nhe1/Af1 II sites of pEGFP-N2. A PCR fragment containing the anti-sense sequence of this construct was then generated using the forward primer 5’ ACTGCTAGCAATACGACTCACTATAGGCAAGCTTACATTCTAACTGCAACCT 3’ and the reverse primer 5’ACTAAGCTTTTCCAAAATAAAATTTAAAT 3’. This PCR product was subsequently inserted into the HindIII site of pcDNA3. The plasmid encoding Random 3 was constructed by first amplifying the sense sequence of human heat shock protein B3 (HSPB3) gene with the forward primer 5’ ATGCCCTATAAATAGCCGTTCATT 3’ and the reverse primer 5’ GCTGGCATTGTTGGAATAATAAGA 3’. Subsequently, a PCR fragment containing the anti-sense sequence of this construct was generated using the forward primer 5’ ATAGGGCCCGCATTCCGTGCTATGATTCA 3’ and the reverse primer 5’ GACGGTACCCTTCATAAAAATCATAGCAAAT 3’. This PCR product was inserted into the KpnI and ApaI sites of pcDNA3. The forward and reverse primers used for RT-PCR of β-globin RNA were 5’ ATGGTGCACCTGACTCCTGA’ and 5’ CACCAGCCACCACTTTCTGA’, respectively. The UAP56 rabbit polyclonal antibody, which cross-reacts with its >90% identical relative URH4945, 46, was raised against full-length GST-UAP5640 and used at a dilution of 1:1000. The Aly rabbit polyclonal antibody was raised against full-length GST-Aly and used at a dilution of 1:1000. The tubulin monoclonal antibody was obtained from Sigma and used at a dilution of 1:1000.

Cell Culture and RNAi

HeLa cells were transfected with siRNAs using lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) on 35 mm dishes with glass coverslip bottoms (MatTek Corp., MA). The siRNA target sequences for URH49 and UAP56 were 5’ AAAGGCCUAGCCAUCACUUUU3’ and 5’AAGGGCUUGGCUAUCACAUUU3’, respectively46 (note that both UAP56 and its >90% identical homolog URH49 must be knocked down to observe a robust export block45, 46). The control non-targeting siRNA was purchased from Dharmacon (catalog # D-001810-04-20).

DNA microinjection, FISH, and IF

HeLa cells used for microinjection were plated on fibronectin-coated 35-mm dishes with glass coverslip bottoms (MatTek) 41. Plasmid DNA (50 ng/µl) was co-injected with FITC-conjugated 70-kDa dextran (Molecular Probes)41. In each experiment, 50–70 cells were microinjected, followed by incubation at 37°C41. After 30 mins of incubation, α-amanitin (50 µg/ml) was added, and incubation was continued for the indicated times. A 70 bp FISH probe 5’ AAGGC ACGGGGGAGGGGCAAACAAC AGATGGCTGGC AACTAGAAGGCAC AGTCGAGGCTGATCAGCGGGT3’ that hybridizes to pcDNA 3.1 vector sequence was labeled at the 5’ end with Alexa Fluor 546 NHS Ester and HPLC purified. For β-globin splicing assays, probes corresponding to splicing junction 2 (splice junction probe) 5’CACAGACCAGCACGTTGCCCAGGAGCCTGAAGTTCTCAGGATCCACGTGC3’ , exon 3-intron 2 junction (exon-intron junction probe) 5’CACAGACCAGCACGTTGCCCAGGAGCTGTGGGAGGAAGATAAGAGGTATG 3’, and intron 2 (intron probe) 5’ATTCCAAATAGTAATGTACTAGGCAGACTGTG TAAAGTTTTTTTTTAAGTTACTTAATGT3’ were labeled with ULYSIS Alexa Fluor nucleic acid labeling kits 647, 546, and 546, respectively (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). For FISH to detect RNAs generated from microinjected CMV-DNA constructs, HeLa cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 mins and permeabilized with 0.1% TritonX-100 in PBS for 15 mins41. Cells were then washed with 50% formamide in 1x SSC and incubated at 37°C with FISH probes for 24 hrs41. For FISH to detect polyA+ RNA, an HPLC-purified oligo dT(70) probe labeled at the 5’ end with Alexa Fluor 546 NHS Ester was used. HeLa cells were washed once with PBS, fixed for 10 mins with 4% paraformaldehyde, washed three times with PBS, permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 5 mins, washed twice with PBS and then once with 2X SSC for 10 mins at RT. The oligo dT(70) probe was then added at 1 ng/µl followed by incubation for 16–24 hrs at 42° C. The cells were washed 15 mins each, twice with 2X SSC, once with 0.5X SSC, and once with PBS at RT. Images were captured with an EM-CCD camera on an inverted microscope (200M; Zeiss, Thornwood, NY) or a Nikon Ti w/Spinning Disk Confocal microscope using Metamorph software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). FISH quantitation was carried out using imageJ 1.33u software (National Institutes of Health)41. For detecting CMV-DNA constructs after microinjection into HeLa cells, PCR constructs were generated using 5’Alexa-647 labeled forward primer 5’TGGAGGTCGCTGAGTAGTGC3’ and reverse primer 5’CCACACCCTAACTGACAC3’. Alexa-647 labeled PCR products were microinjected at a concentration of 50 ng/µl. IF was performed by incubating fixed cells in primary antibody for 30 mins at RT. After washing three times in PBS for 10 mins each, cells were incubated in the secondary antibody for 30 mins at RT, followed by three washes in PBS for 10 mins each. The SC35 primary antibody (Sigma) was diluted to 1:1000 using 10% calf serum in PBS. The Mouse Alexa-647 (1:1000), mouse Alexa-555 (1:1000) and mouse Alexa-350 (1:50) (Invitrogen) secondary antibodies were diluted into 10% calf serum.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank B. Lee, E. Folco, and R. Das for useful discussions, the National Cell Center (Minneapolis, MN) for HeLa cells, and the Nikon Imaging Center at Harvard Medical School for confocal microscopy facilities. This work was supported by an NIH grant to R.R.

Footnotes

Author Contributions A.D. carried out microinjection and confocal microscopy. A.D. and K.D. carried out westerns, RT-PCR, FISH, IF and knockdowns. H.L. constructed plasmids encoding Random 1, 2, and 3 transcripts. R.R., K.D., and A.D wrote the manuscript.

Author Information The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Maniatis T, Reed R. An extensive network of coupling among gene expression machines. Nature. 2002;416:499–506. doi: 10.1038/416499a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reed R. Coupling transcription, splicing and mRNA export. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:326–331. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00048-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pandit S, Wang D, Fu XD. Functional integration of transcriptional and RNA processing machineries. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:260–265. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhong XY, Wang P, Han J, Rosenfeld MG, Fu XD. SR proteins in vertical integration of gene expression from transcription to RNA processing to translation. Mol Cell. 2009;35:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hall LL, Smith KP, Byron M, Lawrence JB. Molecular anatomy of a speckle. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2006;288:664–675. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.20336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawrence JB, Clemson CM. Gene associations: true romance or chance meeting in a nuclear neighborhood? J Cell Biol. 2008;182:1035–1038. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200808121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jensen TH, Dower K, Libri D, Rosbash M. Early formation of mRNP: license for export or quality control? Mol Cell. 2003;11:1129–1138. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00191-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olesen JR, Libri D, Jensen TH. A link between transcription and mRNP quality in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. RNA Biol. 2005;2:45–48. doi: 10.4161/rna.2.2.1633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vanacova S, Stefl R. The exosome and RNA quality control in the nucleus. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:651–657. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rougemaille M, Villa T, Gudipati RK, Libri D. mRNA journey to the cytoplasm: attire required. Biol Cell. 2008;100:327–342. doi: 10.1042/BC20070143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xing Y, Johnson CV, Dobner PR, Lawrence JB. Higher level organization of individual gene transcription and RNA splicing. Science. 1993;259:1326–1330. doi: 10.1126/science.8446901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xing Y, Johnson CV, Moen PT, Jr, McNeil JA, Lawrence J. Nonrandom gene organization: structural arrangements of specific pre-mRNA transcription and splicing with SC-35 domains. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:1635–1647. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.6.1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hattinger CM, Jochemsen AG, Tanke HJ, Dirks RW. Induction of p21 mRNA synthesis after short-wavelength UV light visualized in individual cells by RNA FISH. J Histochem Cytochem. 2002;50:81–89. doi: 10.1177/002215540205000109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shopland LS, Johnson CV, Lawrence JB. Evidence that all SC-35 domains contain mRNAs and that transcripts can be structurally constrained within these domains. J Struct Biol. 2002;140:131–139. doi: 10.1016/s1047-8477(02)00507-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith KP, Moen PT, Wydner KL, Coleman JR, Lawrence JB. Processing of endogenous pre-mRNAs in association with SC-35 domains is gene specific. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:617–629. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.4.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson C, et al. TrackingCOL1A1 RNA in osteogenesis imperfectasplice-defective transcripts initiate transport from the gene but are retained within the SC35 domain. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:417–432. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.3.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Melcak I, Melcakova S, Kopsky V, Vecerova J, Raska I. Prespliceosomal assembly on microinjected precursor mRNA takes place in nuclear speckles. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:393–406. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.2.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tokunaga K, et al. Nucleocytoplasmic transport of fluorescent mRNA in living mammalian cells: nuclear mRNA export is coupled to ongoing gene transcription. Genes Cells. 2006;11:305–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2006.00936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishihama Y, Tadakuma H, Tani T, Funatsu T. The dynamics of pre-mRNAs and poly(A)+ RNA at speckles in living cells revealed by iFRAP studies. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314:748–762. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Funatsu T. [Single-molecule imaging and quantification of mRNAs in a living cell] Yakugaku Zasshi. 2009;129:265–272. doi: 10.1248/yakushi.129.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown JM, et al. Association between active genes occurs at nuclear speckles and is modulated by chromatin environment. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:1083–1097. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200803174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu Q, et al. Enhancing nuclear receptor-induced transcription requires nuclear motor and LSD1-dependent gene networking in interchromatin granules. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19199–19204. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810634105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takizawa T, Gudla PR, Guo L, Lockett S, Misteli T. Allele-specific nuclear positioning of the monoallelically expressed astrocyte marker GFAP. Genes Dev. 2008;22:489–498. doi: 10.1101/gad.1634608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lamond AI, Spector DL. Nuclear speckles: a model for nuclear organelles. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:605–612. doi: 10.1038/nrm1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prasanth KV, et al. Regulating gene expression through RNA nuclear retention. Cell. 2005;123:249–263. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pawlicki JM, Steitz JA. Primary microRNA transcript retention at sites of transcription leads to enhanced microRNA production. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:61–76. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200803111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pawlicki JM, Steitz JA. Subnuclear compartmentalization of transiently expressed polyadenylated pri-microRNAs: processing at transcription sites or accumulation in SC35 foci. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:345–356. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.3.7494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao R, Bodnar MS, Spector DL. Nuclear neighborhoods and gene expression. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2009;19:172–179. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reed R, Cheng H. TREX, SR proteins and export of mRNA. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:269–273. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moore MJ, Proudfoot NJ. Pre-mRNA processing reaches back to transcription and ahead to translation. Cell. 2009;136:688–700. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reed R, Hurt E. A conserved mRNA export machinery coupled to pre-mRNA splicing. Cell. 2002;108:523–531. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00627-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kohler A, Hurt E. Exporting RNA from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:761–773. doi: 10.1038/nrm2255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saguez C, Olesen JR, Jensen TH. Formation of export-competent mRNP: escaping nuclear destruction. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:287–293. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sommer P, Nehrbass U. Quality control of messenger ribonucleoprotein particles in the nucleus and at the pore. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:294–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rougemaille M, et al. THO/Sub2p functions to coordinate 3'-end processing with gene-nuclear pore association. Cell. 2008;135:308–321. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carmody SR, Wente SR. mRNA nuclear export at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:1933–1937. doi: 10.1242/jcs.041236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou Z, et al. The protein Aly links pre-messenger-RNA splicing to nuclear export in metazoans. Nature. 2000;407:401–405. doi: 10.1038/35030160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luo MJ, et al. Pre-mRNA splicing and mRNA export linked by direct interactions between UAP56 and Aly. Nature. 2001;413:644–647. doi: 10.1038/35098106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Masuda S, et al. Recruitment of the human TREX complex to mRNA during splicing. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1512–1517. doi: 10.1101/gad.1302205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheng H, et al. Human mRNA export machinery recruited to the 5' end of mRNA. Cell. 2006;127:1389–1400. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Valencia P, Dias AP, Reed R. Splicing promotes rapid and efficient mRNA export in mammalian cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:3386–3391. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800250105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luo M, Reed R. Splicing is required for rapid and efficient mRNA export in metazoans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:14937–14942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Misteli T. Protein dynamics: implications for nuclear architecture and gene expression. Science. 2001;291:843–847. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5505.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith KP, Byron M, Johnson C, Xing Y, Lawrence JB. Defining early steps in mRNA transport: mutant mRNA in myotonic dystrophy type I is blocked at entry into SC-35 domains. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:951–964. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200706048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee CS, et al. Human DDX3 functions in translation and interacts with the translation initiation factor eIF3. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:4708–4718. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kapadia F, Pryor A, Chang TH, Johnson LF. Nuclear localization of poly(A)+ mRNA following siRNA reduction of expression of the mammalian RNA helicases UAP56 and URH49. Gene. 2006;384:37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fleckner J, Zhang M, Valcarcel J, Green MR. U2AF65 recruits a novel human DEAD box protein required for the U2 snRNP-branchpoint interaction. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1864–1872. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.14.1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shen H, et al. Distinct activities of the DExD/H-box splicing factor hUAP56 facilitate stepwise assembly of the spliceosome. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1796–1803. doi: 10.1101/gad.1657308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Carter KC, Taneja KL, Lawrence JB. Discrete nuclear domains of poly(A) RNA and their relationship to the functional organization of the nucleus. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:1191–1202. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.5.1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Visa N, Puvion-Dutilleul F, Harper F, Bachellerie JP, Puvion E. Intranuclear distribution of poly(A) RNA determined by electron microscope in situ hybridization. Exp Cell Res. 1993;208:19–34. doi: 10.1006/excr.1993.1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang S, Deerinck TJ, Ellisman MH, Spector DL. In vivo analysis of the stability and transport of nuclear poly(A)+ RNA. J Cell Biol. 1994;126:877–899. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.4.877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Melcak I, et al. Nuclear pre-mRNA compartmentalization: trafficking of released transcripts to splicing factor reservoirs. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:497–510. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.2.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Molenaar C, Abdulle A, Gena A, Tanke HJ, Dirks RW. Poly(A)+ RNAs roam the cell nucleus and pass through speckle domains in transcriptionally active and inactive cells. J Cell Biol. 2004;165:191–202. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200310139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kotake Y, et al. Splicing factor SF3b as a target of the antitumor natural product pladienolide. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:570–575. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Okada M, Jang SW, Ye K. Akt phosphorylation and nuclear phosphoinositide association mediate mRNA export and cell proliferation activities by ALY. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:8649–8654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802533105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hautbergue GM, et al. UIF, a New mRNA export adaptor that works together with REF/ALY, requires FACT for recruitment to mRNA. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1918–1924. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.09.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Custodio N, et al. Inefficient processing impairs release of RNA from the site of transcription. Embo J. 1999;18:2855–2866. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.10.2855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ohno M, Segref A, Kuersten S, Mattaj IW. Identity elements used in export of mRNAs. Mol Cell. 2002;9:659–671. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00454-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rodrigues JP, et al. REF proteins mediate the export of spliced and unspliced mRNAs from the nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:1030–1035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.031586198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Das R, Reed R. Reolution of the mammalian E complex and the ATP-dependent spliceosomal complexes on native agarose mini-gels. RNA. 1999;5:1504–1508. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299991501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.