Abstract

Background:

Few studies in Nigeria have investigated HIV risk behavior among persons with severe mental disorders. This study examined HIV risk behavior and associated factors among patients receiving treatment at a Nigerian psychiatric hospital.

Aim:

To determine the HIV risk behavior in persons with severe mental disorders in a psychiatric hospital.

Subjects and Methods:

This was a cross-sectional survey involving 102 persons with serious mental disorders receiving treatment at a major psychiatric facility in Southwestern Nigeria. HIV risk screening instrument was self-administered to assess HIV risk behavior. A questionnaire was used to elicit socio-demographic variables while alcohol use was assessed with the alcohol use disorder identification test. Differences in HIV risk levels were examined for statistical significance using Chi square test.

Results:

Forty eight percent of the respondents engaged in HIV risk behavior. This study revealed that 10.8% (11/102) gave a history of sexually transmitted disease, 5.9% (6/102) reported sex trading and no reports of intravenous drug use was obtained. A single risk factor was reported by 19.6% (20/102), 12.7% (13/102) reported two risk factors and 15.7% (16/102) reported three or more risk factors. HIV risk behavior was significantly related to alcohol use (P = 0.03).

Conclusion:

Mental health services provide an important context for HIV/AIDS interventions in resource-constrained countries like Nigeria.

Keywords: Human immuno virus, Mental health, Psychiatric patients, Risk behavior, Severe mental disorders

Introduction

Persons living with mental illness are particularly vulnerable to HIV/AIDS.[1] This is supported by the range of HIV infection rates of 3.1-22.9% among psychiatric patients in high-income countries.[2,3] One study in Zimbabwe reported a rate of 23.8%.[4] A number of factors make persons with mental illness vulnerable to HIV/AIDS. First, substance use which occurs frequently among psychiatric patients may also contribute to HIV/AIDS. This may due to impaired decision making (especially during intoxication) or shared traits predicting substance use and high-risk behavior, e.g., sensation seeking and impulsivity.[5] Second, cognitive challenges and negative symptoms may limit ability to comprehend and retain information about HIV/AIDS causation, treatment, and prognosis.[6] This may potentially influence behavior and attitude to HIV/AIDS. Third, psychopathologic and behavioral changes associated with mental disorders, e.g., disinhibition, increased libido, and impaired judgment may increase exposure to risky situations.[7] In addition to these factors, increased risk of sexual victimization may occur in the context of vagrancy. In low-income settings, this may be attributed to peculiar challenges of mental healthcare delivery. For instance, less than 10% of persons with severe mental illness (SMI) have access to mental health services in Nigeria.[8] In addition there is widespread stigmatization of the mentally ill poverty and lack of social security.[9,10,11,12]

Previous studies have identified high-risk lifestyles such as injection drug use, unprotected sexual intercourse, and having multiple sexual partners as possible vulnerability factors in spread of HIV/AIDS.[1,2,13,14] In high-income countries the prevalence of HIV risk behavior ranges from 4% to 48%.[6,15] Apart from methodological differences, cultural, and social norms may account for these varying rates. A number of factors have been associated with risky behavior among persons with mental disorders. In the United States, younger age, being single, ethnicity, female gender, and heavy drinking were reported to be associated with risky behavior.[16,17,18] In another study, male sex, being single, and using or abusing substances were identified as predictors of HIV risk behavior in India.[13]

Nigeria currently has about 3.5 million people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) and had 388,000 new infections in 2011.[19] This expanding population of people living with HIV makes Nigeria the country with the second heaviest burden of HIV in Africa.[19] Many PLWHA have comorbid psychiatric disorders including depression, substance use, and post-traumatic stress disorder.[20,21,22] For instance, in Southwestern Nigeria, 59% of a group of HIV-positive individuals had a comorbid psychiatric disorder. This prevalence was significantly higher than that identified among similar individuals who were not affected by HIV.[21] These factors place a huge burden on the nation's economic and healthcare system. It is therefore important to examine the extent and pattern of risk behavior. A high prevalence of risky behavior in specific populations including students,[23,24] commercial sex workers,[25,26] and military personnel,[27,28] has been documented in Nigeria. However, there is a dearth of evidence on the psychosocial factors related to HIV risk behavior among the mentally ill in Nigeria. Research evaluating HIV risk behavior in this vulnerable population of patients is needed to guide the development of effective risk reduction programs.

This study aimed to determine the prevalence of HIV risk behavior and associated demographic and clinical variables among patients with mental disorders in a major psychiatric hospital in Southwestern Nigeria.

Subjects and Methods

Study information

This was a cross-sectional study of persons with mental disorders presenting for evaluation and treatment at the major psychiatric hospital in Ogun state, Nigeria. This is a Federal Government owned specialist institution. It has a total capacity of 526 beds for inpatient care. Even though it receives patients from all parts of the country, majority (89%) of its patients are from Southwestern Nigeria.[29] The hospital provides in-patient, outpatient, and 24-h emergency services to mentally ill patients and primary care services to neighboring communities. Most of the attending patients have major psychiatric disorders including schizophrenia and affective disorders.

Instruments

Socio-demographic questionnaire

A questionnaire was used to elicit the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents. It included information on respondents sex, age, marital status, occupation, highest educational level, and employment status.

HIV risk screening instrument (HSI)

This is a 10-item instrument that evaluates sexual-risk information including number of sexual partners, number of partner-risk characteristics (e.g., injection drug use, multiple partners), and unprotected vaginal intercourse in the past 10 years.[30] The HSI has been used in health care settings to identify individuals at risk for HIV and to initiate HIV testing, early care, and risk-reduction counseling, necessary goals for effective HIV prevention efforts. It has good internal consistency of 0.73.[30] A score of zero reflects low-risk, whereas a score of one or more reflects possible risk for HIV infection.[30]

Alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT-C)

The AUDIT-C is an abbreviated version of the AUDIT consisting of the first three items of AUDIT. It has been found to have good psychometric properties including sensitivity, predictive validity compared with the 10-item questionnaire.[31]

Ethical approval was obtained from the Research and Ethical Committee of the Neuropsychiatric Hospital, Abeokuta. Written informed consent was obtained from the subjects after full explanation of the study. To ensure confidentiality, information was obtained during interviews in the consulting rooms. Questionnaires were serially numbered to ensure anonymity.

Patients aged 18 years and above attending, the psychiatric hospital within the study period that met the inclusion criteria were consecutively recruited till the required sample size was met. Subjects that were acutely ill or did not understand English or Yoruba were excluded from the interview. The instruments were translated to Yoruba using the back translation method. Both instruments have been used in psychiatric populations in previous studies.[13]

Data analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 16.0 (Chicago IL, USA) was used for data analysis. Difference between HIV risk levels were examined for statistical significance using Chi-square test for categorical variables with Yates’ Correction implemented where appropriate. The level of significance (P) was set at < 0.05.

Results

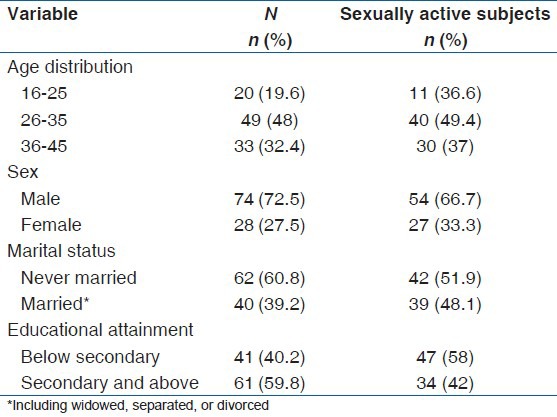

Out of 105 patients approached, 102 (97.1%) participated in the study. Seventy four (72.5%) were male and 28 (27.5%) were female. The mean (SD) age was 32.9 (8.9) years. About 90.2% (92/102) had Schizophrenia and related psychosis while 9.8% (10/102) had affective disorders. Majority of the respondents were never married (60.8%) and had attained secondary level education (86.3%). Eighty two respondents comprising 79.4% of the respondents had a lifetime history of sexual activity. Majority of the sexually active respondents were aged 26-35 years (49.4%), never married (51.9%), and less educated (58%) [Table 1]. Alcohol use in the past year was reported by 40.4% (38/94) of the respondents. Among sexually-active respondents, about 80.8% (63/78) engaged in inconsistent condom use.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of persons with mental disorders

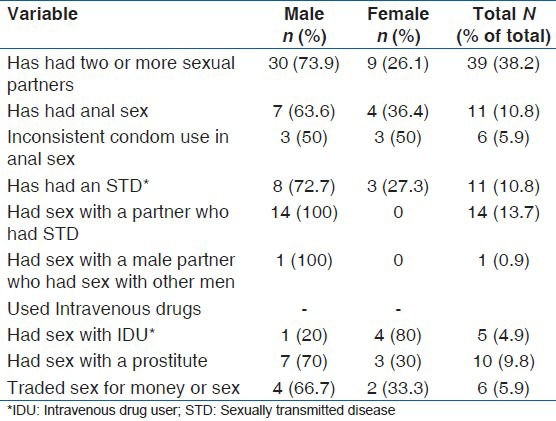

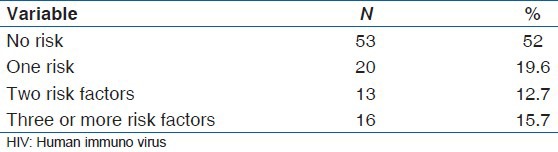

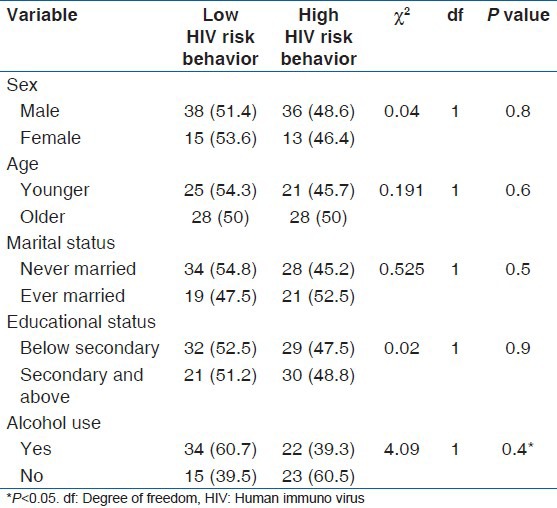

HIV risk behavior among respondents

Forty eight percent of the respondents engaged in HIV risk behavior. Thirty nine (38.2%) reported two or more sexual partners, 10.8% (11/102) reported a sexually transmitted disease (STD), 5.9% (6/102) reported sex trading, and no reports of intravenous drug use were made [Table 2]. 19.6% (20/102) reported a single risk factor, 12.7% (13/102) had two risk factors, and 15.7% (16/102) had three or more risk factors [Table 3]. From Table 4, gender (P = 0.84), age (P = 0.65), marital status (P = 0.45), and educational attainment (P = 0.90) were not associated with HIV risk behavior. However, alcohol use (P = 0.03) was significantly related to HIV risk behavior [Table 4].

Table 2.

Risky behavior among respondents

Table 3.

HIV risk factors among persons with serious mental illness

Table 4.

Psychosocial factors and human immuno virus risk behavior

Discussion

This study showed that HIV risk behavior is quite high among patients with major mental disorders attending a psychiatric hospital in Southwestern Nigeria. This agrees with previous studies in Nigeria and developed countries like United States, India, and Brazil.[13,14,32,33] Unlike a previous local study, a report of a wider range of HIV risk behavior including anal sex and having male partners who have sex with men was found in this population.[14] Though lower than rates of risky sexual behavior reported among military personnel, commercial sex workers, and injection drug users in Nigeria, the high prevalence of risky behavior in this group of persons with SMI is quite disturbing considering the incidence of HIV/AIDS in Nigeria.[19,25,27,34]

HIV risk behavior was found to be associated with alcohol use in this study. This is consistent with the findings in high-income countries[33,35] and has been attributed to the effects of alcohol including impaired judgment,[36] increased vulnerability to sexual assault[37], and reinforcement according to alcohol myopia theory.[38] In a large scale epidemiological study of the prevalence of substance use in Nigeria, lifetime and 12-month prevalence rates of 56% and 14%, respectively, were reported for alcohol use. High rates of alcohol use were similarly reported among PLWHAs in Northern Nigeria.[39,40] Further research is required to determine if the relationship between alcohol use and HIV risk behaviors is state or trait dependent.[41]

This study had its limitations. First, persons classified as being at high risk for HIV may not necessarily be at risk in view of the difficulties associated with determining magnitude of actual risk involved with specific HIV risk factors.[30] Second, the cross-sectional nature limits inferences on direction of causality. Third, the use of a convenience sample raises the possibility of selection bias and limit generalizability. Nevertheless, this is one of the few studies examining the correlates of HIV risk behavior among Nigerians with mental disorders. The use of standardized instruments makes its findings comparable with those of other countries. Fourth, there may have been bias associated with use of non- validated scales to assess HIV risk and alcohol use.

This study showed that there is high prevalence of HIV risk behavior among mentally ill patients in a Nigerian hospital despite ongoing HIV prevention efforts in the country. In order to reduce the impact of HIV/AIDS on the country, evidence based prevention programs tailored to the needs of the population are required. For instance, extant programs targeting voluntary counseling and testing seekers have been reported to be effective.[42] Mental health care settings may provide appropriate opportunities for such HIV risk reduction interventions.[43] Improved knowledge may increase their ability to accurately assess and respond to risky situations. Also, it may reduce stigma and improve access to treatment.[14] This is especially relevant to persons with serious mental illness who are already burdened with the stigma of mental illness and its complications.[7]

There is a need to evaluate current HIV-prevention initiatives within mental health settings in order to make them more effective in reducing the burden of HIV/AIDS in the country. If possible, interventional efforts including psychoeducation, voluntary, counseling, and testing should be built into the process of evaluating and managing persons with SMI presenting at primary, secondary, and tertiary healthcare levels to address HIV risky behavior. Collaborations between HIV and mental health service providers should be strengthened to facilitate early intervention for people with serious mental illness and HIV/AIDS.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Collins RL, Taylor SL, Elliott MN, Ringel JS, Kanouse DE, Beckman R. Off-premise alcohol sales policies, drinking, and sexual risk among people living with HIV. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1890–2. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.158543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKinnon K, Cournos F, Herman R. HIV among people with chronic mental illness. Psychiatr Q. 2002;73:17–31. doi: 10.1023/a:1012888500896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenberg SD, Goodman LA, Osher FC, Swartz MS, Essock SM, Butterfield MI, et al. Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C in people with severe mental illness. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:31–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Acuda SW, Sebit MB. Serostatus surveillance testing of HIV-I infection among Zimbabwean psychiatric inpatients, in Zimbabwe. Cent Afr J Med. 1996;42:254–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carey MP, Carey KB, Maisto SA, Gordon CM, Schroder KE, Vanable PA. Reducing HIV-risk behavior among adults receiving outpatient psychiatric treatment: Results from a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:252–68. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKinnon K, Cournos F, Sugden R, Guido JR, Herman R. The relative contributions of psychiatric symptoms and AIDS knowledge to HIV risk behaviors among people with severe mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57:506–13. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v57n1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collins PY, Holman AR, Freeman MC, Patel V. What is the relevance of mental health to HIV/AIDS care and treatment programs in developing countries? A systematic review. AIDS. 2006;20:1571–82. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000238402.70379.d4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gureje O, Lasebikan VO, Kola L, Makanjuola VA. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of mental disorders in the Nigerian survey of mental health and well-being. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:465–71. doi: 10.1192/bjp.188.5.465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gureje O, Lasebikan VO, Ephraim-Oluwanuga O, Olley BO, Kola L. Community study of knowledge of and attitude to mental illness in Nigeria. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:436–41. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.5.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uwakwe R. The financial (material) consequences of dementia care in a developing country: Nigeria. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2001;15:56–7. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200101000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amoo G. Comparativestudyof the costs of inpatient management of schizophrenia and diabetes mellitus. Unpublished dissertation. West African College of Physicians. 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kabir M, Iliyasu Z, Abubakar IS, Aliyu MH. Perception and beliefs about mental illness among adults in Karfi village, Northern Nigeria. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2004;4:3. doi: 10.1186/1472-698X-4-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chandra PS, Carey MP, Carey KB, Prasada Rao PS, Jairam KR, Thomas T. HIV risk behaviour among psychiatric inpatients: Results from a hospital-wide screening study in southern India. Int J STD AIDS. 2003;14:532–8. doi: 10.1258/095646203767869147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ogunsemi OO, Lawal RA, Okulate GT, Alebiosu CO, Olatawura MO. A comparative study of HIV/AIDS: The knowledge, attitudes, and risk behaviors of schizophrenic and diabetic patients in regard to HIV/AIDS in Nigeria. Med Gen Med. 2006;8:42. doi: 10.1186/1758-2652-8-4-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carey MP, Carey KB, Weinhardt LS, Gordon CM. Behavioral risk for HIV infection among adults with a severe and persistent mental illness: Patterns and psychological antecedents. Community Ment Health J. 1997;33:133–42. doi: 10.1023/a:1022423417304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carey MP, Carey KB, Maisto SA, Gleason JR, Gordon CM, Brewer KK. HIV risk behavior among outpatients at a state psychiatric hospital: Prevalence and risk modeling. Behav Ther. 1999;30:389–406. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(99)80017-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carey MP, Carey KB, Maisto SA, Gordon CM, Vanable PA. Prevalence and correlates of sexual activity and HIV-related risk behavior among psychiatric outpatients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:846–50. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.69.5.846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Otto-Salaj LL, Heckman TG, Stevenson LY, Kelly JA. Patterns, predictors and gender differences in HIV risk among severely mentally ill men and women. Community Ment Health J. 1998;34:175–90. doi: 10.1023/a:1018745119578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abuja, Nigeria: Federal Government of Nigeria; 2012. Nigeria 2012 Global AIDS Response Progress Report (GARPR) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farley J, Miller E, Zamani A, Tepper V, Morris C, Oyegunle M, et al. Screening for hazardous alcohol use and depressive symptomatology among HIV-infected patients in Nigeria: Prevalence, predictors, and association with adherence. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic) 2010;9:218–26. doi: 10.1177/1545109710371133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adewuya AO, Afolabi MO, Ola BA, Ogundele OA, Ajibare AO, Oladipo BF, et al. Relationship between depression and quality of life in persons with HIV infection in Nigeria. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2008;38:43–51. doi: 10.2190/PM.38.1.d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adewuya AO, Afolabi MO, Ola BA, Ogundele OA, Ajibare AO, Oladipo BF, et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after stigma related events in HIV infected individuals in Nigeria. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009;44:761–6. doi: 10.1007/s00127-009-0493-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olley BO. Child sexual abuse, harmful alcohol use and age as determinants of sexual risk behaviours among freshmen in a Nigerian university. Afr J Reprod Health. 2008;12:75–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harding AK, Anadu EC, Gray LA, Champeau DA. Nigerian university students’ knowledge, perceptions, and behaviours about HIV/AIDS: Are these students at risk? J R Soc Promot Health. 1999;119:23–31. doi: 10.1177/146642409911900105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eromonsele SA. Nigeria: MPH Dissertation of the University of Ibadan; 2002. Perceivedsusceptibility to HIV/AIDS and pattern of condom use among female sex workers in two cities in Osun state, Nigeria. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oyefara JL. Food insecurity, HIV/AIDS pandemic and sexual behaviour of female commercial sex workers in Lagos metropolis, Nigeria. SAHARA J. 2007;4:626–35. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2007.9724884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nwokoji UA, Ajuwon AJ. Knowledge of AIDS and HIV risk-related sexual behavior among Nigerian naval personnel. BMC Public Health. 2004;4:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-4-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Olley BO, Bolajoko AJ. Psychosocial determinants of HIV-related quality of life among HIV-positive military in Nigeria. Int J STD AIDS. 2008;19:94–8. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2007.007134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neuropsychiatric Hospital 2010 Annual Report Neuropsychiatric Hospital, Aro. Abeokuta, Ogun State, Nigeria [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gerbert B, Bronstone A, McPhee S, Pantilat S, Allerton M. Development and testing of an HIV-risk screening instrument for use in health care settings. Am J Prev Med. 1998;15:103–13. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meneses-Gaya C, Zuardi AW, Loureiro SR, Hallak JE, Trzesniak C, de Azevedo Marques JM, et al. Is the full version of the AUDIT really necessary? Study of the validity and internal construct of its abbreviated versions. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:1417–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wainberg ML, McKinnon K, Elkington KS, Mattos PE, Gruber Mann C, De Souza Pinto D, et al. HIV risk behaviors among outpatients with severe mental illness in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. World Psychiatry. 2008;7:166–72. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2008.tb00190.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carey MP, Carey KB, Maisto SA, Schroder KE, Vanable PA, Gordon CM. HIV risk behavior among psychiatric outpatients: Association with psychiatric disorder, substance use disorder, and gender. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2004;192:289–96. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000120888.45094.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adelekan ML, Lawal RA. Drug use and HIV infection in Nigeria: A review of recent findings. Afr J Alcohol Drugs. 2006;5:118–29. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kalichman SC, Kelly JA, Johnson JR, Bulto M. Factors associated with risk for HIV infection among chronic mentally ill adults. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:221–7. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fischhoff B, Quadrel MJ. Adolescent alcohol decisions. Alcohol Health Res World. 1991;15:43–51. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Testa M, Livingston JA, Collins RL. The role of women's alcohol consumption in evaluation of vulnerability to sexual aggression. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;8:185–91. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.8.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steele CM, Josephs RA. Alcohol myopia. Its prized and dangerous effects. Am Psychol. 1990;45:921–33. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.8.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gureje O, Degenhardt L, Olley B, Uwakwe R, Udofia O, Wakil A, et al. A descriptive epidemiology of substance use and substance use disorders in Nigeria during the early 21st century. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;91:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yunusa MA, Obembe A, Ibrahim T, Njoku CH. Prevalence and specific psychosocial factors associated with substance abuse and psychiatric morbidity among patients with HIV infection at Usmanu Danfodiyo University Teaching Hospital, Sokoto State, Nigeria. Afr J Drug Alcohol Stud. 2011;10:11–16. [Google Scholar]

- 41.King KM, Nguyen HV, Kosterman R, Bailey JA, Hawkins JD. Co-occurrence of sexual risk behaviors and substance use across emerging adulthood: Evidence for state- and trait-level associations. Addiction. 2012;107:1288–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03792.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Olley BO. Improving well-being through psycho-education among voluntary counseling and testing seekers in Nigeria: A controlled outcome study. AIDS Care. 2006;18:1025–31. doi: 10.1080/09540120600568756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weinhardt LS, Carey MP, Carey KB. HIV risk reduction for the seriously mentally ill: Pilot investigation and call for research. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1997;28:87–95. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7916(97)00002-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]