Abstract

Background:

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) is a common functional gastrointestinal disorder.

Aims:

To identify demographic factors in patients with IBS.

Subjects and Methods:

One-hundred and fifty three IBS patients seen at Taleghani Hospital Gastroenterology Clinic and met the Rome III criteria and 163 peoples who did not meet IBS criteria were consecutively enrolled. Both groups were asked to complete a self-rating questionnaire containing information, which included questions about age, sex, monthly income, education level, marital status, height, weight, alcohol drinking and smoking habits. Student's t-test, Pearson's Chi-square and logistic regression were used to statistical analysis.

Results:

The mean (SD) age for IBS patients 36.3 (13.5) years and 33.1 (9.9) years in non-IBS group (P < 0.001). Frequency of IBS defined by Rome III criteria was higher in females and younger individuals. Univariate analysis showed that IBS in males was associated with a lower monthly income and educational level and in females younger age, single, lower monthly income and educational level, body mass index (BMI), and unemployment status. Multivariate logistic regression identified a low level of education in males (Odds ratio [OR] = 3.6, 95% Confidence interval [CI]: 1.4-9.6) and in females, lower education level (OR = 2.4, 95% CI: 1.1-5.2), lower BMI (OR = 0.94, 95% CI: 0.89-0.99), unemployed (OR = 0.31, 95% CI: 0.11-0.85) and smoking (OR = 6.2, 95% CI: 1.03-37.2).

Conclusion:

We identified demographic factors in IBS patients. Being single and having a lower educational level, income, lower BMI and being unemployed were the most important factors associated with IBS, particularly in females.

Keywords: Body mass index, Cross-sectional study, Irritable bowel syndrome, Rome III criteria

Introduction

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS), the most frequent diagnosis made by gastroenterologists, is characterized by abdominal pain, and altered bowel habits, including diarrhea, constipation, or both.[1,2,3,4,5,6,7] IBS affects individuals of all ages, comprising 40% of outpatient consultations and estimated to affect 25-45 million patients in the United States.[8] The prevalence of IBS is 1.1-5.8% in general population and 3-18.4% in Iran.[6,9,10,11] IBS patients are more likely to be female, married, less educated, overweight and obese (body mass index [BMI] > 25).[5] In half of all cases, symptoms start before 35 years of age while almost all report symptoms onset before age 50.[12] Several Iranian studies have been conducted to evaluate epidemiological features of IBS using cross-sectional methodology.[5,6,10,13] The current work aimed to evaluate demographic factors in an IBS population in Iran using a case-control design.

Subjects and Methods

From, October 2010 to October 2011, we performed an unmatched case-control study in Taleghani Hospital Gastroenterology Clinic, Tehran, capital of Iran. Individuals consecutively referred to the clinic and diagnosed with IBS based on Rome III criteria were enrolled (n = 153). Controls (n = 163) were those seen at a non-gastroenterology clinic and who did not meet Rome III criteria.

We used the Persian version of the previously validated Rome III diagnostic questionnaire.[5,14,15,16] The diagnosis of IBS was based on the presence of abdominal pain or discomfort for at least 3 month in the previous 6 month, with 2 or more of the following symptoms: (1) pain improved after defecation, (2) symptoms associated with a change in frequency of stool, and (3) symptoms associated with a change in the form (appearance) of stool. The patients who were diagnosed as having IBS were further categorized into constipation pre-dominant IBS (IBS-C) if they had hard or lumpy stools with no loose, watery mushy or watery stools in the past 3 months; diarrhea pre-dominant IBS (IBS-D) if they had loose, mushy or water stools in the last 3 months with no hard or lumpy stools and mixed IBS (IBS-M) if they had both loose and hard stools in the past 3 months. The diagnosis was confirmed by a gastroenterologist.

Participants were asked to fill in a demographic self-questionnaire that included information about age, gender, marital status, educational level, weight, height, monthly income, occupational status, alcohol drinking and smoking habits. Weight and height information were convert to BMI.

The study received the approval from Ethics Committee and a written consent was provided from each participant.

Statistical analysis

Sample size was determined based on the following assumption: P1 (Prevalence of indicator in cases) = 0.42, P2 (Prevalence of indicator in controls) = 0.18, α = 0.05, β = 0.80. The minimum sample size required was calculated at 70 patients in each group. P1 and P2 were obtained from a pilot study on 50 individuals, including 25 IBS patients and 25 healthy controls. All statistical analysis carried out using SPSS 13.0 software SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Student's t-test was used to compare means of continuous variables. Pearson's Chi-square and contingency tables were performed to test for independence between discrete classifications variables. Independent factors related to IBS were determined by logistic regression. Continuous variables are presented as mean (SD) and other parameters as frequency and percentage. A P value < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

One hundred and fifty-three IBS patients (cases) and 163 patients without IBS study (controls) were enrolled. The mean (SD) age of IBS patients was 36.3 (13.5) years and non-IBS patients was 33.1 (9.9) years (P < 0.001). Of the IBS patients, 62.1% (95/153) were female, 37.9% (58/153) were male and in the control group 39.3% (64/163) and 60.7% (99/163) were male and female respectively. Most IBS patients 35.9% (55/153) had an education level lower than the diploma whereas 66.9% (109/163) in the control group received an education level higher than diploma. There were no statistical differences in smoking status or BMI between cases and controls.

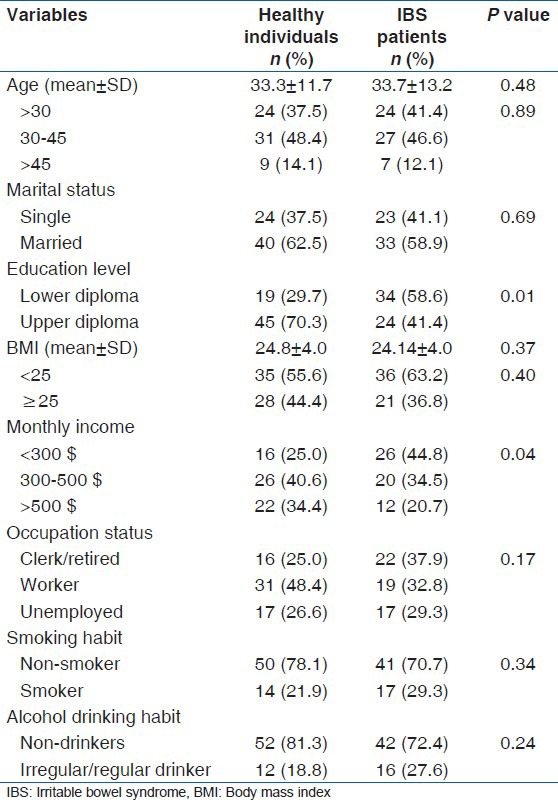

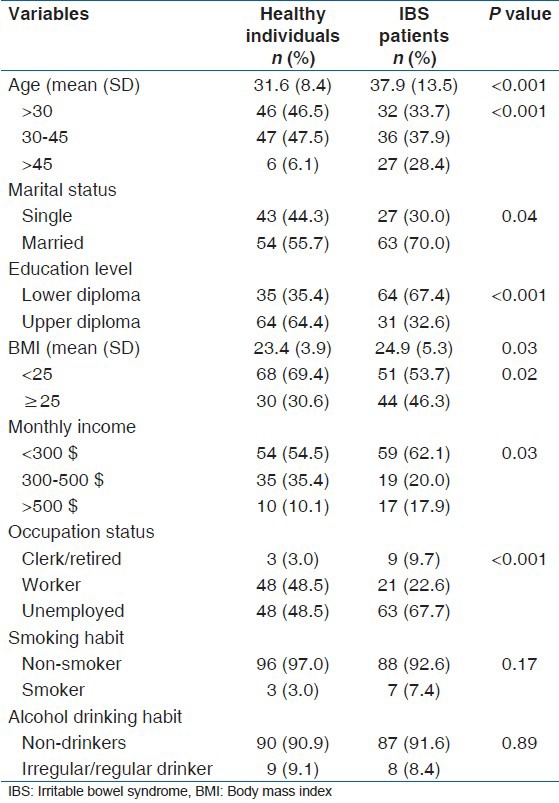

Univariate analysis showed that IBS in males was associated with a lower monthly income (P = 0.04) and educational level (P = 0.001) and in females age (P < 0.001), being unemployed (P < 0.001), single (P = 0.04) and having a lower educational level (P < 0.001), BMI (P = 0.02), and monthly income (P = 0.03) [Tables 1 and 2].

Table 1.

Characteristics of male respondents and statistical comparison between irritable bowel syndrome patients and healthy individuals

Table 2.

Characteristics of female respondents and statistical comparison between irritable bowel syndrome patients and healthy individuals

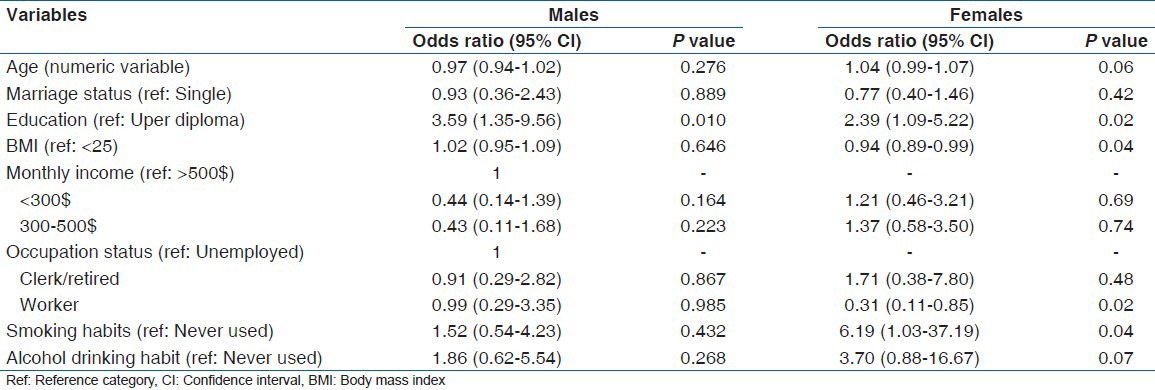

Multivariate logistic regression showed that only low level of education was found in males with IBS (Odds ratio [OR] = 3.6, 95% Confidence interval [CI:] 1.4-9.6). Lower education level (OR = 2.4, 95% CI: 1.1-5.2), BMI (OR = 0.94, 95% CI: 0.89-0.99), unemployed (OR = 0.31, 95% CI: 0.11-0.85) and non-smoker (OR = 6.2, 95% CI: 1.03-37.2) was independently identified IBS in females [Table 3].

Table 3.

Independent factors related to irritable bowel syndrome according to gender

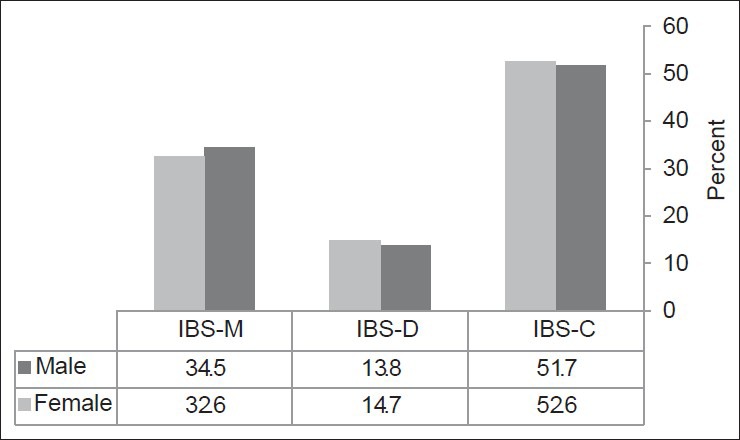

Most of the subjects fulfilling the IBS criteria in both genders were IBS-C (51.7%, 30/58 in males and 52.6%, 50/95 in females), followed by IBS-M and IBS-D [Figure 1]. No statistical differences were seen between male and female regarding subtype of IBS (P = 0.95).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of different subtypes of Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) according to sex of patients. IBS-C: Constipation -pre-dominant subtype, IBS-D: Diarrhea -pre-dominant subtype, IBS-M: Mixed subtype. There is no statistical difference between male and female (P = 0.96)

Discussion

In this clinic-based case-control design, we studied demographic factors in Rome III confirmed IBS patients. Because the diagnosis of IBS depends on criteria used, estimation of true prevalence of IBS may be limited.[2,4,5,6,16,17,18,19] Compared to previous guidelines, Rome III criteria is more specific and restrictive,[5] The time period for diagnosis has been reduced from 12 months, using Rome II criteria to 3 months in Rome III.[20] Using Rome III criteria might have led to the low estimation of IBS in this study.

We found that IBS-C (about 52%, 80/153) with alternating features of mixed subtype (IBS-M) and diarrhea (IBS-D) was the most common form of IBS. A female pre-dominance was seen in our patients diagnosed using Rome III criteria. D No differences were seen among male and female regarding to subtype of IBS (P > 0.05).

In Sorouri et al., study[16] in Iranian general population using Rome III criteria, the majority of cases were IBS-C (45.3%), while the cases with IBS-D (13.4%) were the least common. Another Iranian study on university students using Rome II criteria found IBS-C (50%) as the most frequent and IBS with an alternating stool pattern (IBS-A) as the least frequent subtype (21%).[6] Similarly, in other Asian countries reported that IBS-C was the most frequent subtype (77.4%), and IBS-A and IBS-D comprised 15.5% and 7.1% of IBS patients, respectively.[21] Mearin, et al.[22] in a study conducted in Spain by using Rome II criteria on 2,000 subjects showed that IBS-C (37%) was the most common subtype, followed by IBS-D and IBS-A. Hungin, et al.[23] in their study in USA revealed that IBS-A comprised the majority (66%) of IBS cases, followed by IBS-D (21%) and IBS-C (13%). An international study also found that IBS-A (63%), IBS-D (21%) and IBS-C (16%) to be the most frequent subtypes, respectively.[24] A report from China noted IBS-D to be the most prevalent (74.1%) and IBS-A as the least frequent (10.8%) subtype.[25] In Iran, among IBS patients referred to gastroenterology clinic, Roshandel, et al.[9] reported IBS-A as the most frequent (60%) and IBS-C and IBS-D to be 29.1% and 10.9%, respectively. It seems that in Asia there is no consistency among different studies but in USA and European nations IBS-A maybe the most frequent IBS.

Comparable to other studies we found that about half of male patients and two third of female patients were below the age of 45 years.[26,27,28] One Iranian study revealed that prevalence of IBS was more common in the young decreasing with increasing in age.[13] A similar age trend was identified in a Nigeria population.[29,30] In contrast, no associations have been found between IBS and age China and England.[25,31]

While IBS is more frequent in females than males in Iran[5,13] and many European countries;[17,23,24,32,33] no consistent differences however have been observed in Asian studies. Whereas, a number of studies conducted in Asia have not revealed a gender difference in the prevalence of IBS, others has been reported a female pre-dominance.[19,34,35,36,37] The reason for this controversial sex difference is unknown. It has been suggested that female preponderance is selection bias due to females more likely to seek health care or differences in psychological responses and clinical symptoms between males and females.[38,39]

Consistent with other studies, we found that being single was more common in female patients with.[5,40] Sedentary lifestyle, changing in food habit, psychological factors may account for this finding.

In the present study, IBS was related to unemployed, lower monthly income and low educated. While Andrews, et al.[40] shown a higher prevalence of IBS among persons of lower income, employment and education in the general population, Khoshkrood-Mansoori, et al.[5] found no relationship between the prevalence of IBS and the education level. Unemployment is a risk factor for IBS possibly related to (1) lower income (2) more severe psychological distress compared to employed individuals.

While we have found no association between BMI and IBS in males, a significant association was seen among BMI < 25 and female gender (P < 0.05). Khademolhosseini, et al.[13] in study on 1,978 individuals over 35 years in Shiraz, southern Iran, found no association between IBS and BMI. In contrast, Sorouri, et al.[16] in a population-based study from Tehran, capital of Iran, reported that all subtypes except IBS-D increase with increasing BMI. It is possible that the use of self-reported information may account for differences in BMI score.

Some studies have shown that smoking habit and alcohol consumption is significantly associated with gastrointestinal disorders such as gastroesophageal reflux disease,[41,42,43] uninvestigated dyspepsia,[44,45] abdominal pain[45] and IBS, especially, in female and diarrhea-pre-dominant IBS.[45,46,47,48,49] Halder et al.[45] shown a relationship between alcohol consumption and IBS. We found no association between smoking and alcohol use in patient sibs. These conflicting results might be attributed to the study design, diagnostic criteria used, cultural differences, environmental factors, and small sample size.

This study limitation was that most exposures and outcome measures (such as height, weight) of the study were based on subjective reports. Diagnosis based on patients’ symptoms may lead to an under recognition or misdiagnosis of the disease.

Because of the cross-sectional design and other limitations mentioned above, we believe that these results should be interpreted with caution. Frequency of IBS defined by Rome III criteria was relatively higher in females and younger peoples. Marital status, educational level, occupation, income and BMI were the most important related factors to IBS especially in females. Additional research is required to clarify the role of demographic factors in IBS patients with a larger sample size.

Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Science, Tehran, Iran.

Footnotes

Source of Support: University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Science, Tehran, Iran.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Everhart JE, Renault PF. Irritable bowel syndrome in office-based practice in the United States. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:998–1005. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90275-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Russo MW, Gaynes BN, Drossman DA. A national survey of practice patterns of gastroenterologists with comparison to the past two decades. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;29:339–43. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199912000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson WG, Heaton KW, Smyth GT, Smyth C. Irritable bowel syndrome in general practice: Prevalence, characteristics, and referral. Gut. 2000;46:78–82. doi: 10.1136/gut.46.1.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson WG. Irritable bowel syndrome. Strategy for the family physician. (313-6).Can Fam Physician. 1994;40:307–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khoshkrood-Mansoori B, Pourhoseingholi MA, Safaee A, Moghimi-Dehkordi B, Sedigh-Tonekaboni B, Pourhoseingholi A, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome: A population based study. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2009;18:413–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghannadi K, Emami R, Bashashati M, Tarrahi MJ, Attarian S. Irritable bowel syndrome: An epidemiological study from the west of Iran. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2005;24:225–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mayer EA, Thompson WG, Dent J. Irritable bowel syndrome: Diagnosis, subgrouping, management, and clinical trial design. Introduction. Am J Med. 1999;107:1S–4. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00075-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drossman DA, Li Z, Andruzzi E, Temple RD, Talley NJ, Thompson WG, et al. U.S. Householder survey of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Prevalence, sociodemography, and health impact. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1569–80. doi: 10.1007/BF01303162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roshandel D, Rezailashkajani M, Shafaee S, Zali MR. Symptom patterns and relative distribution of functional bowel disorders in 1,023 gastroenterology patients in Iran. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2006;21:814–25. doi: 10.1007/s00384-006-0117-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoseini-Asl MK, Amra B. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in Shahrekord, Iran. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2003;22:215–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Massarrat S, Saberi-Firoozi M, Soleimani A, Himmelmann GW, Hitzges M, Keshavarz H. Peptic ulcer disease, irritable bowel syndrome and constipation in two populations in Iran. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1995;7:427–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maxwell PR, Mendall MA, Kumar D. Irritable bowel syndrome. Lancet. 1997;350:1691–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)05276-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khademolhosseini F, Mehrabani D, Nejabat M, Beheshti M, Heydari ST, Mirahmadizadeh A, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome in adults over 35 years in Shiraz, southern Iran: Prevalence and associated factors. J Res Med Sci. 2011;16:200–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barzkar M, Pourhoseingholi MA, Habibi M, Moghimi-Dehkordi B, Safaee A, Pourhoseingholi A, et al. Uninvestigated dyspepsia and its related factors in an Iranian community. Saudi Med J. 2009;30:397–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Solhpour A, Safaee A, Pourhoseingholi MA, Moghimi-Dehkordi B, Habibi M, Qafarnejad F, et al. Relationship between uninvestigated dyspepsia and body mass index: A population-based study. East Afr J Public Health. 2010;7:318–22. doi: 10.4314/eajph.v7i4.64755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sorouri M, Pourhoseingholi MA, Vahedi M, Safaee A, Moghimi-Dehkordi B, Pourhoseingholi A, et al. Functional bowel disorders in Iranian population using Rome III criteria. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:154–60. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.65183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones R, Lydeard S. Irritable bowel syndrome in the general population. BMJ. 1992;304:87–90. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6819.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson W, Dotevall G, Drossman D, Heaton K, Kruis W. Irritable bowel syndrome: Guidelines for the diagnosis. Gastroenterol Int. 1989;2:92–5. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho KY, Kang JY, Seow A. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms in a multiracial Asian population, with particular reference to reflux-type symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1816–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dorn SD, Morris CB, Hu Y, Toner BB, Diamant N, Whitehead WE, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome subtypes defined by Rome II and Rome III criteria are similar. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:214–20. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31815bd749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tan YM, Goh KL, Muhidayah R, Ooi CL, Salem O. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in young adult Malaysians: A survey among medical students. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18:1412–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2003.03212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mearin F, Balboa A, Badía X, Baró E, Caldwell E, Cucala M, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome subtypes according to bowel habit: Revisiting the alternating subtype. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:165–72. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200302000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hungin AP, Chang L, Locke GR, Dennis EH, Barghout V. Irritable bowel syndrome in the United States: Prevalence, symptom patterns and impact. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:1365–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hungin AP, Whorwell PJ, Tack J, Mearin F. The prevalence, patterns and impact of irritable bowel syndrome: An international survey of 40,000 subjects. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:643–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xiong LS, Chen MH, Chen HX, Xu AG, Wang WA, Hu PJ. A population-based epidemiologic study of irritable bowel syndrome in South China: Stratified randomized study by cluster sampling. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:1217–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wei X, Chen M, Wang J. The epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome and functional constipation of Guangzhou residents. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 2001;40:517–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Si JM, Chen SJ, Sun LM. An epidemiological and quality of life study of irritable bowel syndrome in Zhejiang province. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 2003;42:34–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gwee KA, Wee S, Wong ML, Png DJ. The prevalence, symptom characteristics, and impact of irritable bowel syndrome in an Asian urban community. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:924–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han SH, Lee OY, Bae SC, Lee SH, Chang YK, Yang SY, et al. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in Korea: Population-based survey using the Rome II criteria. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:1687–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ladep NG, Okeke EN, Samaila AA, Agaba EI, Ugoya SO, Puepet FH, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome among patients attending General Outpatients’ clinics in Jos, Nigeria. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19:795–9. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282202ba5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heaton KW, O’Donnell LJ, Braddon FE, Mountford RA, Hughes AO, Cripps PJ. Symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome in a British urban community: Consulters and non-consulters. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:1962–7. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90320-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ford AC, Talley NJ, Veldhuyzen van Zanten SJ, Vakil NB, Simel DL, Moayyedi P. Will the history and physical examination help establish that irritable bowel syndrome is causing this patient's lower gastrointestinal tract symptoms? JAMA. 2008;300:1793–805. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.15.1793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Makharia GK, Verma AK, Amarchand R, Goswami A, Singh P, Agnihotri A, et al. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome: A community based study from northern India. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;17:82–7. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2011.17.1.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu CL, Chen CY, Lang HC, Luo JC, Wang SS, Chang FY, et al. Current patterns of irritable bowel syndrome in Taiwan: The Rome II questionnaire on a Chinese population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:1159–69. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rajendra S, Alahuddin S. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome in a multi-ethnic Asian population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:704–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01891.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Masud MA, Hasan M, Khan AK. Irritable bowel syndrome in a rural community in Bangladesh: Prevalence, symptoms pattern, and health care seeking behavior. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1547–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheung TK, Lam KF, Hu WH, Lam CL, Wong WM, Hui WM, et al. Positive association between gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and irritable bowel syndrome in a Chinese population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:1099–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chang L, Heitkemper MM. Gender differences in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1686–701. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.36603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kane S. Gender issues in the management of inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome. Int J Fertil Womens Med. 2002;47:136–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Andrews EB, Eaton SC, Hollis KA, Hopkins JS, Ameen V, Hamm LR, et al. Prevalence and demographics of irritable bowel syndrome: Results from a large web-based survey. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:935–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Watanabe Y, Fujiwara Y, Shiba M, Watanabe T, Tominaga K, Oshitani N, et al. Cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption associated with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in Japanese men. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:807–11. doi: 10.1080/00365520310004506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Locke GR, 3rd, Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ., 3rd Risk factors associated with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Med. 1999;106:642–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00121-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Swanson GR, Sedghi S, Farhadi A, Keshavarzian A. Pattern of alcohol consumption and its effect on gastrointestinal symptoms in inflammatory bowel disease. Alcohol. 2010;44:223–8. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2009.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moayyedi P, Forman D, Braunholtz D, Feltbower R, Crocombe W, Liptrott M, et al. The proportion of upper gastrointestinal symptoms in the community associated with Helicobacter pylori, lifestyle factors, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Leeds HELP Study Group. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1448–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.2126_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Halder SL, Locke GR, 3rd, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Talley NJ. Influence of alcohol consumption on IBS and dyspepsia. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18:1001–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2006.00815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Talley NJ, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ., 3rd Irritable bowel syndrome in a community: Symptom subgroups, risk factors, and health care utilization. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142:76–83. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Locke GR, 3rd, Zinsmeister AR, Talley NJ, Fett SL, Melton LJ. Risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: Role of analgesics and food sensitivities. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:157–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reshetnikov OV, Kurilovich SA, Denisova DV, Zavίalova LG, Svetlova IO, Tereshonok IN, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of the development of irritable bowel syndrome in adolescents: A population study. Ter Arkh. 2001;73:24–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kubo M, Fujiwara Y, Shiba M, Kohata Y, Yamagami H, Tanigawa T, et al. Differences between risk factors among irritable bowel syndrome subtypes in Japanese adults. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:249–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]