Abstract

The management of patients with non variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding has evolved, as have its causes and prognosis, over the past 20 years. The addition of high-quality data coupled to the publication of authoritative national and international guidelines have helped define current-day standards of care. This review highlights the relevant clinical evidence and consensus recommendations that will hopefully result in promoting the effective dissemination and knowledge translation of important information in the management of patients afflicted with this common entity.

Keywords: Clips, endoscopic hemostasis, endoscopy, hemostatic powders, injection, non variceal, prokinetic drugs, proton pump inhibitors, thermal coagulation, transfusion, upper gastrointestinal bleeding

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) is a critical condition that requires prompt and effective medical and endoscopic management. Peptic ulcer disease is the most common cause of UGIB, accounting for more than 50% of cases of nonvariceal UGIB (NVUGIB).[1] The incidence of AUGIB in the USA ranges from 48 to 160 cases per 100,000 adults per year.[1] Until recently, the reported mortality from UGIB had remained unchanged around 5-10% despite the advances in therapeutic and endoscopic modalities, probably due to the increased use of aspirin (ASA) and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, in conjunction with the increasing number of multiple comorbidities in an aging population in many countries.[2] However, additional data report an improved mortality rate approximating 2.4-5% with decreased hospitalization, reflecting better risk stratification and advances in medical and endoscopic treatments.[3,4]

In this review article, the state-of-the-art management of acute UGIB, including resuscitation and risk stratification in the emergency department; pre-endoscopic medical treatment; endoscopic hemostasis, including new emerging therapies; and appropriate postendoscopic management, including secondary prophylaxis to reduce recurrent bleeding from peptic ulcer disease (PUD) are discussed.

RESUSCITATION AND INITIAL ASSESSMENT

Airway, breathing, and circulation assessment

Airway, breathing, and circulation (ABC) remain the most crucial steps in the initial assessment of patients presenting with acute UGIB. Airway intubation is required in case of airway compromise; however, there is limited data regarding prophylactic airway intubation in severe acute UGIB.[5,6] The patient should be ideally monitored in a high dependency unit with cardiac monitoring and careful attention to impending signs of multiorgan failure. Venous access should be established with two large bore intravenous cannulae. Minimum blood workup in all patients should include blood-typing and cross-matching for an appropriate number of units of packed red blood cells along with determinations of hemoglobin, hematocrit, platelets, coagulation time, and electrolytes.[7] Hypovolemic shock or its consequences is one of the major causes of mortality in acute UGIB, and therefore prompt and appropriate resuscitation with either crystalloids or colloids, and ideally packed red blood cells, if indicated is required.[8,9]

Red blood cell transfusion

The use of red blood cell (RBC) transfusion in severe acute UGIB depends on multiple factors, the physician, the patient and local hospital guidelines. Adoption of a liberal versus a restrictive strategy depends on the severity of acute UGIB. The value of RBC transfusion is self-evident in severe acute UGIB, and the consequences of anemia should be weighed against the risks associated with transfusion products. Massive transfusion is associated with dilutional coagulopathy. RBC transfusion is rarely indicated in cases where hemoglobin is greater than 100g/L, whereas it is always indicated in cases where hemoglobin is less than 60g/L.[7] A systematic review of 10 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing restrictive versus liberal RBC transfusion strategies in 1780 patients with suspected UGIB from a variety of clinical settings concluded that a restrictive approach led to a 42% reduction in the probability of receiving transfusions with no effect on mortality, rates of cardiac events, morbidity, or length of hospital stay,[10] supporting a restrictive strategy in blood transfusion with a hemoglobin threshold of less than 70g/L. Recently, a randomized trial of patients with suspected UGIB showed decreased mortality and rebleeding in patients managed according to a restrictive blood transfusion approach versus a more liberal one (70 g/L vs. 90 g/L, respectively), after exclusion of patients with massive bleeding and significant cardiovascular disease.[11] However, it is important to note that the data appeared driven by favorable results specifically in the patients with UGIB in the context of chronic liver disease (Child's grades A and B), and that more definitive data for such benefits in patients with NVUGIB are required for confirmation.[10,11]

Correction of coagulopathy

The initial international normalized ratio (INR) in acute UGIB can be of prognostic significance. In the Canadian Registry on Nonvariceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding and Endoscopy (RUGBE) cohort of 1869 patients with NVUGIB, a presenting INR of greater than 1.5 was associated with almost a twofold increased risk of mortality (OR 1.95, 95% CI 1.13-3.41) after adjustment for confounders, but not an increased risk of rebleeding.[12] Another study in patients with UGIB, using a historical cohort comparison, suggested that correcting an INR to less than 1.8 as part of intensive resuscitation led to lower mortality and fewer myocardial infarctions in the intervention group.[13] This has led an international consensus conference to recommend that coagulopathy should be reversed, however it should not delay early endoscopy, which is defined as endoscopy within 24 h of acute UGIB.[1] This approach is further supported by the emergence of new hemostatic modalities, such as hemoclips and hemospray powder, which avoid tissue damage secondary to needle injection or thermal injury provided by the thermal hemostatic modalities. Moreover, limited observational data also suggest that endoscopic hemostasis can be safely performed in patients with an elevated INR as long as it is not supratherapeutic (i.e., up to around 2.5).[14]

The prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC) should be considered in warfarin worsened life-threatening UGIB.[15] Four-factor PCCs, which contain significant amounts of factors II, VII, IX, and X are primarily available in Europe and Canada. Compared with fresh frozen plasma (FFP), these solutions represent lower volumes and can be infused more quickly; however, they are less effective in reversing a coagulopathy secondary to chronic liver disease in the setting of acute UGIB. Data supporting the use of a PCC to reverse the effects of the new anticoagulants, such as dabigatran (direct thrombin inhibitor) are conflicting.[16] Compared with warfarin, dabigatran is associated with more gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, including major GI bleeding.[17,18] Renal impairment extends the elimination half-life of dabigatran from 12 h to anywhere from 17 to 34 h. Up to date a few studies have assessed the combination of PCC and FFP to reverse the effects of these new anticoagulants in the setting of severe UGIB, which appear quite limited, at least in the case of dabigatran.

In contrast to INR, platelet counts have not been shown to be a predictor of either rebleeding or mortality and there is no high-quality evidence to guide transfusion thresholds, although a platelet transfusion threshold of 50 × 109/L has been proposed for most patients, with a target of 100 × 109/L for patients in whom platelet dysfunction is suspected.[19]

RISK STRATIFICATION

There exist well-validated risk stratification scoring systems in the setting of UGIB that helps to stratify patients with UGIB into low-risk or high-risk patients, thus, influencing decisions regarding hospitalization versus prompt safe discharge from the ER, and possibly influencing the ideal time to perform endoscopy.[20]

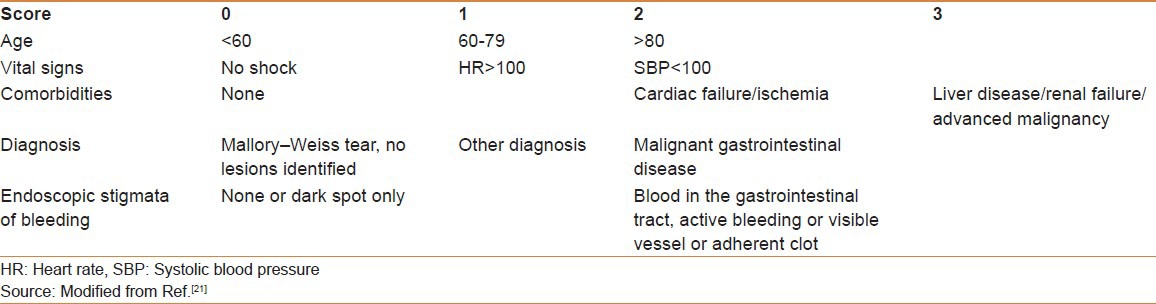

The Rockall score can be calculated using both pre-endoscopic (clinical Rockall) (total = 7) and postendoscopic (total = 11) data. The full Rockall score incorporates both pre- and postendoscopic parameters [Table 1]. It predicts risk for further bleeding and mortality using age (<60, 60-79, and >70 years), the presence of shock (systolic blood pressure <100 mmHg and heart rate >100 beat/min), comorbidities (ischemic heart disease, congestive heart failure, any major comorbidities; and renal or liver failure and disseminated malignancy), and endoscopic diagnosis (Mallory–Weiss tear, PUD, erosive disease, esophagitis, or evidence of malignancy), along with endoscopic findings (blood in stomach, adherent clot, visible vessel, and spurting vessel or pigmented spot or no stigmata).[21] Patients with risk scores of 0 and 1 have low incidences of rebleeding and no associated mortality; allowing the identification of patients at low risk of complications for early discharge.[21]

Table 1.

The full Rockall score

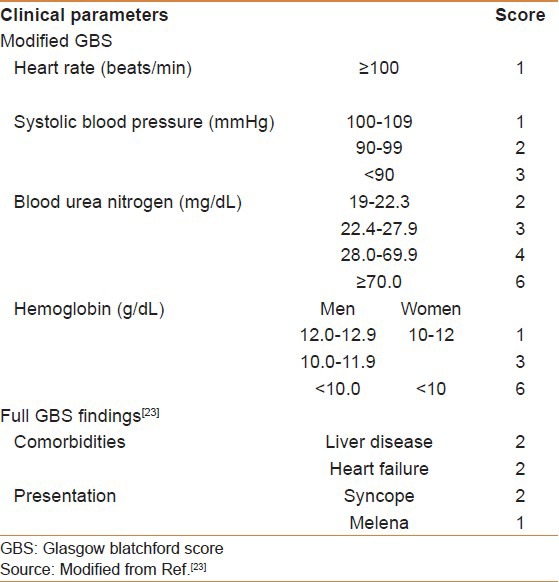

The Glasgow Blatchford score (GBS) was developed to predict the need for intervention in UGIB, that is, transfusions, endoscopic therapy, and surgery [Table 2]. It has the advantage of using only clinical and laboratory data compared with the full Rockall score.[22] The modified GBS and the full GBS outperformed both Rockall scores in predicting clinical outcomes in patients with AUGIB, and by eliminating the subjective components of the GBS, the modified GBS may be easier to use in clinical practice.[23] A GBS of 0 predicts a 0.5% risk for needing subsequent intervention, thus early discharge and outpatient follow up.[24]

Table 2.

The modified GBS and the full GBS

A simple risk score AIMS65 was developed and validated to predict in hospital mortality, length of hospital stay and cost.[25] The following parameters are used: age less than 65 years, systolic blood pressure 90 mmHg or lower, altered mental status, albumin less than 3.0 g/dL, and INR greater than 1.5. For those with no risk factors, the mortality rate was 0.3% compared with 31.8% in patients with all 5 (P < 0.001).

PRE-ENDOSCOPIC THERAPY

Prokinetic drugs

The use of prokinetics before endoscopy may be considered in selected patients. Meta-analyses show that erythromycin is associated with a decreased need for repeat endoscopy in patients with evidence of ongoing active bleeding and blood in the stomach (hematemesis, coffee ground vomiting, or bloody nasogastric aspirate).[26] However, use of erythromycin failed to change outcomes in terms of length of stay, transfusion requirements, and need for surgery.[26] The data stems from limited number of studies and small amount of patients; therefore, the robustness of these conclusions will need to be confirmed with larger trials. Recent guidelines do not support prokinetics routinely, but rather recommend their use in selected patients with evidence of active bleeding and/or blood in the stomach such as hematemesis, coffee ground vomiting, and/or a bloody nasogastric aspirate.[1]

Proton pump inhibitors prior to endoscopy

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) play an important role in the stabilization of clot formation in response to bleeding peptic ulcers through pH-dependent factors, by raising the pH to 6, perhaps helping optimize platelet aggregation.[27] Raising the pH may also decrease pepsin-mediated clot lysis and fibrinolytic activity. A Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis of six RCTs, including 2223 patients comparing PPI with control administrations [placebo or histamine-2 (H2)-receptor antagonists] found no evidence that pre-endoscopic administration of PPIs led to a reduction in the most important clinical outcomes following AUGIB, namely, rebleeding, mortality, or need for surgery.[28] However, the use of pre-endoscopic PPI may delay the need for endoscopic intervention by downstaging high-risk endoscopic ulcer lesions into low risk. This may prove beneficial when early endoscopy is not feasible or local expertise is limited, the use of pre-endoscopic PPI, however, should not replace appropriate initial resuscitation or delay the performance of early endoscopy.[29]

The use of octreotide/somatostatin analogs

The current international recommendations state that somatostatin or octreotide are not recommended in the routine management of patients with acute NVUGIB.[30] RCTs have shown that in patients with a bleeding ulcer following successful endoscopic hemostasis, pantoprazole continuous infusion was superior to somatostatin to prevent bleeding recurrence and promote the disappearance of the endoscopic stigmata. Nevertheless, no differences were seen in the need for surgery or mortality.[31] Such an approach should of course be considered if a variceal cause of bleeding is suspected,[32] or if patients are exsanguinating from any UGIB etiology.

TIMING OF ENDOSCOPY AND PERFORMANCE OF ENDOSCOPIC THERAPY

Timing of endoscopy

The current recommendations in the management of UGIB suggest early endoscopy (defined as within 24 h of presentation) in most patients with NVUGIB.[1] Very early endoscopy (<12 h) when compared with early endoscopy (>12 h and < 24 h) does not seem to confer any additional benefits in terms of rebleeding, need for surgery, or mortality in unselected patients with NVUGIB based on randomized trial findings.[33,34,35] However, Kim et al., recently suggested, using observational data, that endoscopy within 13 h of presentation was associated with a lower mortality in selected high-risk patients, defined as GBS > 12.[36] A window of 12 h after presentation is recommended in patients with variceal bleeding.[32]

Endoscopic therapy

Endoscopic therapy is the cornerstone in the management of UGIB. The traditional modalities can be categorized as injection, mechanical therapy, and thermal approaches. Injection agents include saline, dilute epinephrine, sclerosing agents (polidocanol, ethanolamine, absolute alcohol, and sodium tetradecyl sulfate), and tissue adhesives (cyanoacrylate, thrombin, and fibrin glue). Mechanical therapy includes endoscopic clips and band ligation. Different thermal devices include specialized devices delivering electrical current (through direct contact or via an inert gas plasma) or heat to the target tissue. Recently, a few new technologies have emerged, including hemostatic powders.[37,38]

Indication for endoscopic therapy

Endoscopic therapy is warranted in high-risk lesion, that is, active bleeding, the presence of a nonbleeding visible vessel, or an adherent clot. Indeed, multiple meta-analyses have shown a reduction in the rebleeding rate in patients treated with endoscopic modalities compared with pharmacologic treatment alone. However, diverging results were reported when assessing mortality benefits and reductions in the need for surgery.[39,40,41,42] Finally, there is no benefit of endoscopic treatment of patients with low-risk lesions.[43,44]

Injection agents

Dilute epinephrine is the most widely used injection agent. It is readily available, easy to use, and economical. It achieves hemostasis primarily through local and vascular tamponade, like the other injection agents, but may also trigger vasoconstriction and platelet aggregation.[45,46,47] Epinephrine is usually diluted in normal saline at a concentration of 1:10,000 or 1:20,000 and injected with increments of 0.5-1.5 mL aliquots to the four quadrants around the high-risk stigmata or active bleeding site and then in the middle of it.[48,49] The optimal volume of injection is still a matter of debate. Higher volumes, as high as 30 mL, appear to be more efficacious than lower volumes in achieving initial and long-term hemostasis. However, injection of epinephrine alone does not provide adequate hemostasis and should be used in combination with another modality.[42]

The tissue adhesives, thrombin and fibrin, create a tissue seal at the site of bleeding, in addition to a tamponade effect. Sclerosing agents induce thrombosis through direct tissue injury. They are associated with tissue necrosis, and hence the limit of volume injected is less than 1 mL.[45,46]

Mechanical therapy

Mechanical therapy achieves hemostasis by approximating the submucosa surrounding the bleeding site, causing a tamponade effect.[48] Contrary to injection and cautery, it does not induce tissue injury. The endoscopic clip is the most commonly used mechanical device. Proper positioning and deployment of the clip requires technical skill, and is essential to obtain optimal hemostasis. Furthermore, the localization of the lesion may limit the use of clips, such as the posterior wall and the lesser curvature of the stomach, and the posterior wall of the duodenal bulb.[50] Band ligation is widely used in variceal bleeding and has been found to be effective in bleeding Dieulafoy's lesions and, anecdotally, in some patients bleeding from peptic ulcers.[51,52]

Thermal therapies

Thermal therapies include electrocautery probes (monopolar, bipolar (BEC) or multipolar (MEC)), the heater probe (HP), and the argon plasma coagulator (APC). BEC, MEC, and HP are the most frequently used thermal endoscopic modalities in UGIB. They achieve hemostasis through a two-step process. First, the probe pressure causes vascular occlusion and local tamponade. Second, the application of heat or electrical current leads to coagulation of the vessel. Furthermore, tissue coagulation induces intravascular platelet aggregation. APC can also be used to treat superficial lesions (1-2 mm deep), but does not allow physical compression, so called co-aptive electrocoagulation, because of the risk of submucosal dissection due to the flow of argon gas.[53] Because of a higher risk of perforation, monopolar probes are rarely used in the management of UGIB. BEC/MEC, ideally the 10 French probes, should be applied with firm pressure for 10-12 s delivery, using low power, optimally 15 W.[54] The application should be repeated until the visible vessel becomes flat, the stigmata become properly coagulated, or until the bleeding stops.[55] HP should be manipulated using similar pressure, with repeated pulses delivering 25-30 J of energy per pulse, for a total of 4-5 pulses per application.[53] The reported method of APC use varies, but, in general, the probe should be positioned 2-10 mm from the lesion and argon gas flow should be 1.5-2 L/min and a power of 40-50 W.[56,57]

Comparisons amongst endoscopic modalities

Multiple trials have assessed the efficacy of medical therapy compared with endoscopic mono and combination therapies. Despite considerable heterogeneity among the different trials, all measured similar outcomes of recurrent bleeding, initial hemostasis, need for surgery, and overall mortality. Five recent meta-analyses assessed the optimal endoscopic therapy in bleeding peptic ulcer with high-risk stigmata.[58,59,60,61,62]

All endoscopic modalities showed a benefit in maintaining hemostasis, decreasing rebleeding, lowering the need for surgery, and mortality when compared with medical therapy alone.[44] Epinephrine injection alone was less effective than the other endoscopic modalities, alone or combined with epinephrine injection, at preventing rebleeding. Thus, injection of epinephrine alone, although better than sham or sole medical therapy, should not be used when other endoscopic hemostatic modalities are available. Moreover, when combining hemoclip and injection, most trials have assessed applying the clip before injection of epinephrine. It is hypothesized that the volume injected may interfere with a durable application of the clip.[49]

Treatment of an adherent clot

The role of endoscopic therapy for ulcers with adherent clots is controversial. The definition of an adherent clot is the persistence of the clot, after aggressive washing for more than 5 min. Endoscopic therapy for adherent clots involves injection of epinephrine and shaving or cheese wiring the clot with a snare, without disrupting its pedicle that may be adhering to the bleeding ulcer lesion. Endoscopic therapy is then applied if the uncovered base of the ulcer presents a high-risk lesion.[63,64] The risk for rebleeding with clots that remain adherent after washing without endoscopic therapy (with or without PPI therapy) is controversial as it has been reported to be as low as 0-8%[65] but in other studies as high as 25-35%[63,66,67] in clinically high-risk patients. One meta-analysis of five RCTs,[62] comprising 189 patients with adherent clots, found no significant benefits for endoscopic versus no endoscopic therapy [relative risk (RR), 0.31 (CI, 0.06-1.77)]. The most recent recommendations, accordingly, state that endoscopic therapy may be considered, although intensive PPI therapy alone may be sufficient.[68]

Hemostatic powders

Hemostatic powders are an emerging endoscopic hemostatic technology.[37] They are composed of a proprietary inorganic powders that, when put in contact with moisture in the GI tract, becomes coherent and adhesive, thus serving as an adherent mechanical barrier for hemostasis; they can only bind to a lesion if it is actively bleeding. A prospective, pilot study involving 20 patients with nonmalignant upper GI bleeding showed that the application of TC-325 was associated with a 95% initial hemostasis with no active bleeding seen on repeat gastroscopy at 72 h, followed by total elimination of the inorganic substance without complications, such as intestinal obstruction or embolization.[69] Its optimal role, and the ideal target patient population for these agents remains unclear but the hemostatic powders may best be suited for patients with UGIB lesions exhibiting low rebleeding risks, perhaps past the first 24-48 h, unless an adjunctive hemostatic method is considered at the index or at a subsequent a preplanned second-look endoscopic procedure. The powders may also be useful in the management of patients acutely failing other hemostatic approaches or with massive bleeding. Additional indications might include stabilizing patients for transfer to a facility with greater endoscopic expertise, or as a temporizing measure to provide immediate hemostasis while the effect of irreversible, newer anticoagulant agents such as dabigatran gradually disappears.[70] A report of five patients presenting with malignant UGIB also suggests the efficacy of the hemostatic powder.[71]

POSTENDOSCOPIC THERAPY

Proton pump inhibitors

The modern management of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage includes the performance of timely therapeutic endoscopy followed by an appropriate period of intense acid suppression.[72] The efficacy of IV PPI therapy was most extensively evaluated in a large Cochrane meta-analysis by Leontiadis and colleagues,[73] including 24 RCTs and comprising 4373 patients, which concluded that acute PPI use (omeprazole, lansoprazole, and pantoprazole) reduced rebleeding (odds ratio (OR) 0.49; 95% CI, 0.37-0.65; number needed to treat (NNT) 13], surgical intervention (OR, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.48-0.78; NNT 34), and repeated endoscopic treatment (OR, 0.32; 95% CI, 0.16-0.74; NNT 34). In addition, assessment of the 12 trials that provided data on patients with active bleeding or a nonbleeding visible vessel showed that the PPI significantly decreased mortality (OR 0.53; 95% CI for fixed effect, 0.31-0.91), if performed following successful endoscopic hemostasis. A subsequent meta-analysis by Laine and McQuaid[62] confirmed the above findings, with significant reductions in further bleeding, surgery, and mortality with high-dose IV PPI use compared with placebo.

The issue of PPI dosing postendoscopic hemostasis remains an area of persistent controversy in the management of ulcer bleeding. The current international consensus guidelines admitted that the optimal doing and route of administration remain unknown, yet in light of the strongest available evidence, recommended high-dose IV PPI therapy of 80 mg bolus followed by 8 mg/h for 3 days.[1] Indeed, the authors felt that it was not possible to draw conclusions regarding the comparative efficacy of lower versus higher doses or intravenous versus oral routes, as most studies addressing these issues were either underpowered or lacked generalizability. A subsequent meta-analysis conducted by Wang et al.,[74] including 1157 patients from seven randomized studies, suggested that high-dose PPIs were equivalent to non–high-dose PPIs in reducing the rates of rebleeding, surgical intervention, and mortality when used postendoscopically. However, this meta-analysis assessed studies that included patients with both high- and low-risk lesions and, whose methodological quality was suboptimal. In addition, the observed effect size, total number of patients included in the meta-analysis, and resulting confidence intervals were insufficient to support the claim of equivalence of low- and high-dose intravenous PPI regimens. A very recent RCT from Taiwan[75] showed no difference in rebleeding rates within 30 days between the high-dose group (6.2%; 95% CI, 1.3-11.1%) compared with the standard dose group (5.2%; 95% CI, 0.6-9.7%). Although the trial avoided some of the limitations of previously conducted RCTs on this topic, namely, excluding patients with low-risk endoscopic stigmata and adopting efficacious endoscopic therapy, persistent other methodological flaws limited its internal validity. Indeed, the trial was open-label, and the small observed difference in rebleeding rates of 1% carried wide 95% CI, making it underpowered to draw conclusive recommendations. At the current time, it seems reasonable to continue using a high-dose PPI intravenous regimen for 3 days until new high-quality data become available, as using a less-effective therapy may place patients at risk for adverse outcomes.

Consideration of Helicobacter pylori

The role of H. pylori in PUD has been well documented in the literature since the initial landmark Lancet article by Marshall and Warren in 1983.[76] The current international consensus guidelines support testing patients with bleeding peptic ulcers for H. pylori, and administering eradication therapy if present, with confirmation of eradication.[1] This was confirmed in a meta-analysis, which showed that treatment of H. pylori infection is more effective than antisecretory noneradication therapy (with or without long-term maintenance antisecretory treatment) in the prevention of recurrent bleeding from peptic ulcer.[77] However, the timing of H. pylori testing is unclear due to the potential false-negatives in the setting of acute UGIB, which is thought to be partly due to the alkalotic milieu imparted by the presence of blood in the gastric lumen and the resultant proximal migration of the bacterium, as well as concurrent PPI use.[78] A systematic review of 23 studies, done as part of an international consensus conference on NVUGIB, found that diagnostic tests for H. pylori infection (including serology, histology, urea breath test, rapid urease test, stool antigen, and culture) demonstrated high positive (0.85-0.99) but low negative predictive value (0.45-0.75) in the setting of acute UGIB, with 25-55% of H. pylori–infected patients yielding false-negative results.[1] These findings were confirmed in a subsequent systematic review by Sánchez-Delgado et al., which found that in studies performing a delayed urea breath test after the bleeding episode there was a uniformly higher prevalence of the infection.[79] On the basis of these data, a recommendation to retest all the patients with negative immediate H. pylori test may be a reasonable approach.[1,80]

Patients bleeding who are using aspirin (ASA) and/or clopidogrel

Low-dose ASA (≤325 mg/d) is of definite and substantial benefit for the prevention of vascular disease. In a large meta-analysis from the UK by the Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration, ASA use in patients with established occlusive vascular disease led to a 1.5% absolute reduction in vascular events per year (6.7% vs. 8.2% per year, P < 0.0001, NNT = 67).[81] However, long-term use of low-dose ASA increases the risk of serious GI complications. The absolute risk of UGIB increases with 0.19% per year in patients treated with ASA [number needed to harm (NNH) =526].[81,82]

Among 156 patients presenting with a bleeding ulcer while on ASA for established cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease, Sung et al.[83] randomly allocated the subjects to early ASA reintroduction within days or discontinuation for 2 months. The risk of recurrent bleeding was a nonstatistically significant twofold increase in patients who continued ASA therapy (10.3% vs. 5.4% among those who discontinued the therapy, P = 0.25).

However, there was an eightfold statistically significant increased risk of death among patients who discontinued ASA therapy (1.3% vs. 10.3%, P = 0.005).

These findings were confirmed by a Swedish retrospective cohort study[84] documenting a sevenfold increase in risk for death or acute cardiovascular events (hazard ratio 6.9; 95% CI, 1.4-34.8) in patients who discontinued low-dose ASA compared with those continuing therapy during the first 6 months of follow-up. The current consensus recommendations state that “in patients who receive low-dose ASA and develop acute ulcer bleeding, ASA therapy should be restarted as soon as the risk for cardiovascular complication is thought to outweigh the risk for bleeding.”[1] This is thought to occur 7-10 days (and as early as 5 days) after cessation of ASA therapy as the number of inhibited platelets in the circulation is reduced and the risk for major adverse cardiac events increases.[82] Our practice is to reassess the indication for continued ASA therapy, and if deemed necessary to resume ASA therapy within 3-5 days of achieving endoscopic hemostasis.

H. pylori infection has been shown to be an important risk factor for the development of duodenal ulceration for patients on ASA therapy (OR 18.5, 95% CI, 2.3-149.4).[85] Chan et al.[86] reported data demonstrating that H. pylori eradication was equivalent to treatment with PPI in preventing recurrent bleeding in patients on low-dose ASA with a prior history of UGIB. The same group subsequently published their long-term data,[87] which confirmed that the long-term risk of recurrent ulcer bleeding with ASA use is low after eradication of H. pylori. In contrast, ASA users without past or current H. pylori infection had an eightfold increased incidence rate of recurrent UGIB, emphasizing the added importance of PPI cotherapy in the latter group.

Two studies looked at the use of antisecretory agents in patients on ASA with no prior history of PUD. A large, international, multicenter trial assessed the efficacy of esomeprazole in reducing the risk of gastroduodenal ulceration and dyspeptic symptoms. Esomeprazole use resulted in a reduction of erosive esophagitis (4.4% vs. 18.3%; P < 0.001) as well as PUD (1.8% vs. 6.2%; P < 0.001), respectively, over 26 weeks compared with placebo.[88] The FAMOUS[89] trial evaluated the role of famotidine versus placebo, and it was found to be efficacious in reducing the incidence of gastric (OR, 0.20; 95% CI, 0.09-0.47) and duodenal ulcers (OR, 0.05; 95% CI, 0.01-0.4) compared with placebo. However, these were all low-risk patients who may not require PPI prophylaxis in the first place. In contrast, among patients with previous history of PUD, a head-to-head comparison of high-dose famotidine (40 mg twice daily) versus pantoprazole (20 mg daily) showed that the H2-receptor antagonist was clearly inferior to PPI in preventing recurrent bleeding PUD [7.7% (5/65) vs. 0% (0/65); 95% one-sided CI for the risk difference, 0.0226-1.0; P = 0.0289].[90]

On the other hand, the data for PPI and clopidogrel remains less clear. A large, retrospective cohort study from Taiwan of patients at high risk for major GI complications found that only the combination of PPI plus ASA, but not clopidogrel, was associated with a reduced risk of recurrent hospitalization for major GI complications.[91] In H. pylori–negative patients, the combination of ASA plus PPI resulted in a reduction in recurrent bleeding compared with clopidogrel use alone.[1,86,92] More recent data evaluating the PPI plus clopidogrel combination revealed that incidence of recurrent peptic ulcer was 1.2% among patients given esomeprazole and clopidogrel (n = 83) and 11.0% among patients given clopidogrel alone (n = 82) (difference, 9.8%; 95% CI, 2.6-17.0%; P = 0.009). Interestingly, the study showed no effect of the combination therapy on platelet aggregation tests.[93]

For patients on dual antiplatelet therapy [DAPT (ASA + clopidogrel)], the COGENT[94,95] trial showed that the rate of overt UGIB was reduced with omeprazole as compared with placebo (hazard ratio, 0.13; 95% CI, 0.03-0.56; P = 0.001), without an associate increase in cardiovascular events, bringing into question the clinical relevance of any possible PPI-clopidogrel interaction, although the study was underpowered for this outcome. An authoritative systematic review appears to confirm this interpretation.[96] A recently published RCT compared the efficacy of esomeprazole versus famotidine in the prevention of GI complications (bleeding, obstruction, or perforation) in patients with ACS/acute STEMI, who are on ASA, clopidogrel, and enoxaparin or thrombolytic therapy. Esomeprazole was found to be superior to famotidine, with only one (0.6%) patient in the PPI group versus nine (6.1%) in the H2-receptor antagonist group reached the primary end point (log-rank test, P = 0.0052, hazard ratio = 0.095, 95% CI, 0.005-0.504).[97]

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barkun AN, Bardou M, Kuipers EJ, Sung J, Hunt RH, Martel M, et al. International consensus recommendations on the management of patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:101–13. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Imperiale TF, Dominitz JA, Provenzale DT, Boes LP, Rose CM, Bowers JC, et al. Predicting poor outcome from acute upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1291–6. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.12.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Leerdam ME, Vreeburg EM, Rauws EA, Geraedts AA, Tijssen JG, Reitsma JB, et al. Acute upper GI bleeding: Did anything change? Time trend analysis of incidence and outcome of acute upper GI bleeding between 1993/1994 and 2000. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1494–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07517.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Longstreth GF. Epidemiology of hospitalization for acute upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: A population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:206–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rehman A, Iscimen R, Yilmaz M, Khan H, Belsher J, Gomez JF, et al. Prophylactic endotracheal intubation in critically ill patients undergoing endoscopy for upper GI hemorrhage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:e55–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rudolph SJ, Landsverk BK, Freeman ML. Endotracheal intubation for airway protection during endoscopy for severe upper GI hemorrhage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:58–61. doi: 10.1067/mge.2003.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jairath V, Barkun AN. The overall approach to the management of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2011;21:657–70. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blatchford O, Davidson LA, Murray WR, Blatchford M, Pell J. Acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage in west of Scotland: Case ascertainment study. BMJ. 1997;315:510–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7107.510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Incidence of and mortality from acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage in the United Kingdom. Steering Committee and members of the National Audit of Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Haemorrhage. BMJ. 1995;311:222–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6999.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jairath V, Kahan BC, Logan RF, Travis SP, Palmer KR, Murphy MF. Red blood cell transfusion practice in patients presenting with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding: A survey of 815 UK clinicians. Transfusion. 2011;51:1940–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2011.03119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Villanueva C, Colomo A, Bosch A, Concepcion M, Hernandez-Gea V, Aracil C, et al. Transfusion strategies for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:11–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shingina A, Barkun AN, Razzaghi A, Martel M, Bardou M, Gralnek I. Systematic review: The presenting international normalised ratio (INR) as a predictor of outcome in patients with upper nonvariceal gastrointestinal bleeding. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:1010–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baradarian R, Ramdhaney S, Chapalamadugu R, Skoczylas L, Wang K, Rivilis S, et al. Early intensive resuscitation of patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding decreases mortality. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:619–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choudari CP, Rajgopal C, Palmer KR. Acute gastrointestinal haemorrhage in anticoagulated patients: Diagnoses and response to endoscopic treatment. Gut. 1994;35:464–6. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.4.464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogawa S, Szlam F, Ohnishi T, Molinaro RJ, Hosokawa K, Tanaka KA. A comparative study of prothrombin complex concentrates and fresh-frozen plasma for warfarin reversal under static and flow conditions. Thromb Haemost. 2011;106:1215–23. doi: 10.1160/TH11-04-0240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eerenberg ES, Kamphuisen PW, Sijpkens MK, Meijers JC, Buller HR, Levi M. Reversal of rivaroxaban and dabigatran by prothrombin complex concentrate: A randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study in healthy subjects. Circulation. 2011;124:1573–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.029017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagarakanti R, Ezekowitz MD, Oldgren J, Yang S, Chernick M, Aikens TH, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: An analysis of patients undergoing cardioversion. Circulation. 2011;123:131–6. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.977546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, Eikelboom J, Oldgren J, Parekh A, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1139–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Razzaghi A, Barkun AN. Platelet transfusion threshold in patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding: A systematic review. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:482–6. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31823d33e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laine L, Jensen DM. Management of patients with ulcer bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:345–60. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Risk assessment after acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Gut. 1996;38:316–21. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.3.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blatchford O, Murray WR, Blatchford M. A risk score to predict need for treatment for upper-gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Lancet. 2000;356:1318–21. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02816-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng DW, Lu YW, Teller T, Sekhon HK, Wu BU. A modified Glasgow Blatchford Score improves risk stratification in upper gastrointestinal bleed: A prospective comparison of scoring systems. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:782–9. doi: 10.1111/apt.12029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stanley AJ, Ashley D, Dalton HR, Mowat C, Gaya DR, Thompson E, et al. Outpatient management of patients with low-risk upper-gastrointestinal haemorrhage: Multicentre validation and prospective evaluation. Lancet. 2009;373:42–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61769-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saltzman JR, Tabak YP, Hyett BH, Sun X, Travis AC, Johannes RS. A simple risk score accurately predicts in-hospital mortality, length of stay, and cost in acute upper GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1215–24. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barkun AN, Bardou M, Martel M, Gralnek IM, Sung JJ. Prokinetics in acute upper GI bleeding: A meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:1138–45. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barkun AN, Cockeram AW, Plourde V, Fedorak RN. Review article: Acid suppression in non-variceal acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:1565–84. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1999.00623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leontiadis GI, Sreedharan A, Dorward S, Barton P, Delaney B, Howden CW, et al. Systematic reviews of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of proton pump inhibitors in acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Health Technol Assess. 2007;11:3–4. doi: 10.3310/hta11510. 1-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barkun AN. Should every patient with suspected upper GI bleeding receive a proton pump inhibitor while awaiting endoscopy? Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:1064–6. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barkun A, Bardou M, Marshall JK. Consensus recommendations for managing patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:843–57. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-10-200311180-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsibouris P, Zintzaras E, Lappas C, Moussia M, Tsianos G, Galeas T, et al. High-dose pantoprazole continuous infusion is superior to somatostatin after endoscopic hemostasis in patients with peptic ulcer bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1192–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, Carey W. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46:922–38. doi: 10.1002/hep.21907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bjorkman DJ, Zaman A, Fennerty MB, Lieberman D, Disario JA, Guest-Warnick G. Urgent vs. elective endoscopy for acute non-variceal upper-GI bleeding: An effectiveness study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)01287-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee JG, Turnipseed S, Romano PS, Vigil H, Azari R, Melnikoff N, et al. Endoscopy-based triage significantly reduces hospitalization rates and costs of treating upper GI bleeding: A randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:755–61. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70154-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin HJ, Wang K, Perng CL, Chua RT, Lee FY, Lee CH, et al. Early or delayed endoscopy for patients with peptic ulcer bleeding. A prospective randomized study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1996;22:267–71. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199606000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lim LG, Ho KY, Chan YH, Teoh PL, Khor CJ, Lim LL, et al. Urgent endoscopy is associated with lower mortality in high-risk but not low-risk nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2011;43:300–6. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Giday SA, Kim Y, Krishnamurty DM, Ducharme R, Liang DB, Shin EJ, et al. Long-term randomized controlled trial of a novel nanopowder hemostatic agent (TC-325) for control of severe arterial upper gastrointestinal bleeding in a porcine model. Endoscopy. 2011;43:296–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sung JJ, Luo D, Wu JC, Ching JY, Chan FK, Lau JY, et al. Early clinical experience of the safety and effectiveness of Hemospray in achieving hemostasis in patients with acute peptic ulcer bleeding. Endoscopy. 2011;43:291–5. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chan FK, Ching JY, Hung LC, Wong VW, Leung VK, Kung NN, et al. Clopidogrel versus aspirin and esomeprazole to prevent recurrent ulcer bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:238–44. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garcia-Iglesias P, Villoria A, Suarez D, Brullet E, Gallach M, Feu F, et al. Meta-analysis: Predictors of rebleeding after endoscopic treatment for bleeding peptic ulcer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:888–900. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Al-Sabah S, Barkun AN, Herba K, Adam V, Fallone C, Mayrand S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of proton-pump inhibition before endoscopy in upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:418–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vergara M, Calvet X, Gisbert JP. Epinephrine injection versus epinephrine injection and a second endoscopic method in high risk bleeding ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;2:CD005584. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005584.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sacks HS, Chalmers TC, Blum AL, Berrier J, Pagano D. Endoscopic hemostasis. An effective therapy for bleeding peptic ulcers. JAMA. 1990;264:494–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.264.4.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cook DJ, Guyatt GH, Salena BJ, Laine LA. Endoscopic therapy for acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: A meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:139–48. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91793-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hwang JH, Fisher DA, Ben-Menachem T, Chandrasekhara V, Chathadi K, Decker GA, et al. The role of endoscopy in the management of acute non-variceal upper GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:1132–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Savides TJ, Jensen DM. Therapeutic endoscopy for nonvariceal gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2000;29:465–87. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(05)70123-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.O’Brien JR. Some Effects of Adrenaline and Anti-Adrenaline Compounds on Platelets in Vitro and in Vivo. Nature. 1963;200:763–4. doi: 10.1038/200763a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kovacs TO, Jensen DM. Endoscopic therapy for severe ulcer bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2011;21:681–96. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2011.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lo CC, Hsu PI, Lo GH, Lin CK, Chan HH, Tsai WL, et al. Comparison of hemostatic efficacy for epinephrine injection alone and injection combined with hemoclip therapy in treating high-risk bleeding ulcers. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:767–73. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.11.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gralnek IM, Barkun AN, Bardou M. Management of acute bleeding from a peptic ulcer. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:928–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0706113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alis H, Oner OZ, Kalayci MU, Dolay K, Kapan S, Soylu A, et al. Is endoscopic band ligation superior to injection therapy for Dieulafoy lesion? Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1465–9. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0255-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Park CH, Lee WS, Joo YE, Choi SK, Rew JS, Kim SJ. Endoscopic band ligation for control of acute peptic ulcer bleeding. Endoscopy. 2004;36:79–82. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jensen DM, Machicado GA. Endoscopic hemostasis of ulcer hemorrhage with injection, thermal, and combination methods. Tech Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;7:124–31. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Laine L, Long GL, Bakos GJ, Vakharia OJ, Cunningham C. Optimizing bipolar electrocoagulation for endoscopic hemostasis: Assessment of factors influencing energy delivery and coagulation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:502–8. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jensen DM. Spots and clots-leave them or treat them? Why and how to treat. Can J Gastroenterol. 1999;13:413–5. doi: 10.1155/1999/703461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang HM, Hsu PI, Lo GH, Chen TA, Cheng LC, Chen WC, et al. Comparison of hemostatic efficacy for argon plasma coagulation and distilled water injection in treating high-risk bleeding ulcers. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:941–5. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31819c3885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Karaman A, Baskol M, Gursoy S, Torun E, Yurci A, Ozel BD, et al. Epinephrine plus argon plasma or heater probe coagulation in ulcer bleeding. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4109–12. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i36.4109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Calvet X, Vergara M, Brullet E, Gisbert JP, Campo R. Addition of a second endoscopic treatment following epinephrine injection improves outcome in high-risk bleeding ulcers. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:441–50. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marmo R, Rotondano G, Piscopo R, Bianco MA, D’Angella R, Cipolletta L. Dual therapy versus monotherapy in the endoscopic treatment of high-risk bleeding ulcers: A meta-analysis of controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:279–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.01023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sung JJ, Tsoi KK, Lai LH, Wu JC, Lau JY. Endoscopic clipping versus injection and thermo-coagulation in the treatment of non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: A meta-analysis. Gut. 2007;56:1364–73. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.123976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Barkun AN, Martel M, Toubouti Y, Rahme E, Bardou M. Endoscopic hemostasis in peptic ulcer bleeding for patients with high-risk lesions: A series of meta-analyses. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:786–99. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Laine L, McQuaid KR. Endoscopic therapy for bleeding ulcers: An evidence-based approach based on meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:33–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bleau BL, Gostout CJ, Sherman KE, Shaw MJ, Harford WV, Keate RF, et al. Recurrent bleeding from peptic ulcer associated with adherent clot: A randomized study comparing endoscopic treatment with medical therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:1–6. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.125365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kahi CJ, Jensen DM, Sung JJ, Bleau BL, Jung HK, Eckert G, et al. Endoscopic therapy versus medical therapy for bleeding peptic ulcer with adherent clot: A meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:855–62. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.06.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sung JJ, Chan FK, Lau JY, Yung MY, Leung WK, Wu JC, et al. The effect of endoscopic therapy in patients receiving omeprazole for bleeding ulcers with nonbleeding visible vessels or adherent clots: A randomized comparison. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:237–43. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-4-200308190-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lau JY, Chung SC, Leung JW, Lo KK, Yung MY, Li AK. The evolution of stigmata of hemorrhage in bleeding peptic ulcers: A sequential endoscopic study. Endoscopy. 1998;30:513–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1001336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jensen DM, Kovacs TO, Jutabha R, Machicado GA, Gralnek IM, Savides TJ, et al. Randomized trial of medical or endoscopic therapy to prevent recurrent ulcer hemorrhage in patients with adherent clots. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:407–13. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.34782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Barkun AN, Bardou M, Kuipers EJ, Sung J, Hunt RH, Martel M, et al. International consensus recommendations on the management of patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:101–13. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-2-201001190-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Giday SA. Preliminary data on the nanopowder hemostatic agent TC-325 to control gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 2011;7:620–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Barkun AN, Moosavi S, Martel M. Topical hemostatic agents: A systematic review with particular emphasis on endoscopic application in GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:692–700. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chen YI, Barkun AN, Soulellis C, Mayrand S, Ghali P. Use of the endoscopically applied hemostatic powder TC-325 in cancer-related upper GI hemorrhage: Preliminary experience (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:1278–81. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Greenspoon J, Barkun A. The pharmacological therapy of non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2010;39:419–32. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2010.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Leontiadis GI, Sharma VK, Howden CW. Proton pump inhibitor treatment for acute peptic ulcer bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;1:CD002094. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002094.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang CH, Ma MH, Chou HC, Yen ZS, Yang CW, Fang CC, et al. High-dose vs non-high-dose proton pump inhibitors after endoscopic treatment in patients with bleeding peptic ulcer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:751–8. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chen CC, Lee JY, Fang YJ, Hsu SJ, Han ML, Tseng PH, et al. Randomised clinical trial: High-dose vs. standard-dose proton pump inhibitors for the prevention of recurrent haemorrhage after combined endoscopic haemostasis of bleeding peptic ulcers. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:894–903. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2012.05047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Marshall B, Warren JR. Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet. 1984;323:1311–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91816-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gisbert JP, Khorrami S, Carballo F, Calvet X, Gene E, Dominguez-Munoz E. Meta-analysis: Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy vs. antisecretory non-eradication therapy for the prevention of recurrent bleeding from peptic ulcer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:617–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.McColl KE. Clinical practice. Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1597–604. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1001110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sanchez-Delgado J, Gene E, Suarez D, Garcia-Iglesias P, Brullet E, Gallach M, et al. Has H. pylori prevalence in bleeding peptic ulcer been underestimated?. A meta-regression. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:398–405. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Trawick EP, Yachimski PS. Management of non-variceal upper gastrointestinal tract hemorrhage: Controversies and areas of uncertainty. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1159–65. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.11.1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Antithrombotic Trialists’ (ATT) Collaboration. Baigent C, Blackwell L, Collins R, Emberson J, Godwin J, Peto R, et al. Aspirin in the primary and secondary prevention of vascular disease: Collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised trials. Lancet. 2009;373:1849–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60503-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Struijk M, Postma DF, van Tuyl SA, van de Ree MA. Optimal drug therapy after aspirin-induced upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Eur J Intern Med. 2012;23:227–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sung JJ, Lau JY, Ching JY, Wu JC, Lee YT, Chiu PW, et al. Continuation of low-dose aspirin therapy in peptic ulcer bleeding: A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:1–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-1-201001050-00179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Derogar M, Sandblom G, Lundell L, Orsini N, Bottai M, Lu Y, et al. Discontinuation of low-dose aspirin therapy after peptic ulcer bleeding increases risk of death and acute cardiovascular events. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yeomans ND, Lanas AI, Talley NJ, Thomson AB, Daneshjoo R, Eriksson B, et al. Prevalence and incidence of gastroduodenal ulcers during treatment with vascular protective doses of aspirin. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:795–801. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chan FK, Chung SC, Suen BY, Lee YT, Leung WK, Leung VK, et al. Preventing recurrent upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with Helicobacter pylori infection who are taking low-dose aspirin or naproxen. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:967–73. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103293441304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chan FK, Ching JY, Suen BY, Tse YK, Wu JC, Sung JJ. Effects of Helicobacter pylori infection on long-term risk of peptic ulcer bleeding in low-dose aspirin users. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:528–35. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Yeomans N, Lanas A, Labenz J, van Zanten SV, van Rensburg C, Racz I, et al. Efficacy of esomeprazole (20 mg once daily) for reducing the risk of gastroduodenal ulcers associated with continuous use of low-dose aspirin. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2465–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Taha AS, McCloskey C, Prasad R, Bezlyak V. Famotidine for the prevention of peptic ulcers and oesophagitis in patients taking low-dose aspirin (FAMOUS): A phase III, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374:119–25. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61246-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ng FH, Wong SY, Lam KF, Chu WM, Chan P, Ling YH, et al. Famotidine is inferior to pantoprazole in preventing recurrence of aspirin-related peptic ulcers or erosions. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:82–8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hsiao FY, Tsai YW, Huang WF, Wen YW, Chen PF, Chang PY, et al. A comparison of aspirin and clopidogrel with or without proton pump inhibitors for the secondary prevention of cardiovascular events in patients at high risk for gastrointestinal bleeding. Clin Ther. 2009;31:2038–47. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lai KC, Lam SK, Chu KM, Wong BC, Hui WM, Hu WH, et al. Lansoprazole for the prevention of recurrences of ulcer complications from long-term low-dose aspirin use. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:2033–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hsu PI, Lai KH, Liu CP. Esomeprazole with clopidogrel reduces peptic ulcer recurrence, compared with clopidogrel alone, in patients with atherosclerosis. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:791–8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Almadi MA, Barkun A, Brophy J. Antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy in patients with gastrointestinal bleeding: An 86-year-old woman with peptic ulcer disease. JAMA. 2011;306:2367–74. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bhatt DL, Cryer BL, Contant CF, Cohen M, Lanas A, Schnitzer TJ, et al. Clopidogrel with or without omeprazole in coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1909–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1007964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lima JP, Brophy JM. The potential interaction between clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors: A systematic review. BMC Med. 2010;8:81. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ng FH, Tunggal P, Chu WM, Lam KF, Li A, Chan K, et al. Esomeprazole compared with famotidine in the prevention of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with acute coronary syndrome or myocardial infarction. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:389–96. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]