Abstract

Background:

An effective response to health problems is completely dependent upon the capacities of the health system in providing timely and valid information to take action. This study was designed to identify various reasons from various perspectives for underreporting disease by physicians in the private sector in big cities in developing countries setting.

Methods:

In this qualitative study, we used focus group discussions (16 manager), and in-depth semi-structured interviews

Results:

Themes were classified in 6 categories: Infrastructure and legal issues, the priority of disease reporting, workflow processes, motivation and attitude, human resources and knowledge and awareness. As the main reasons of under reporting, most physicians pointed out complicacy in reporting process and inadequate attention by the public sector. Managers emphasized instituting legal incentives and penalties. Experts focused on physicians’ knowledge and expressed a need for continuing medical education programs.

Conclusions:

Independent interventions will have little chance of success and sustainability. Different intervention programs should consider legal issues, attitude and knowledge of physicians in the private sector, and building a simple reporting process for physicians. Intervention programs in which the reporting process offers incentives for all stakeholders can help improving and sustaining the disease reporting system.

Keywords: Iran, notification, public health practice, reporting

INTRODUCTION

An effective response to health problems is completely dependent upon the capacities of the health system in providing timely and valid information to take action.[1] In this regard, a health surveillance system is one of the fundamental organizations to provide epidemiologic estimates concerning diseases and their trends.[2] A surveillance system is not only a vital instrument in response to emerging and re-emerging disease, but also essential for evaluating the effectiveness of current health interventions and programs.[3] A health surveillance system can also identify vulnerable groups and monitor short and long term disease trends.[4]

The health surveillance systems in Iran has achieved outstanding results in terms of vaccine-preventable disease and mother and child health care.[5] In the Eastern Mediterranean Region, Iran is one of the countries which has successfully eradicated dracunculiasis, eliminated neonatal tetanus, and controlled tuberculosis; yet despite reaching standards in eradication, leptospirosis shows a high incidence in some of Iran's provinces.[5] Efforts to eradicate acute flaccid paralysis control disease such as leishmaniasis, sexually transmitted disease, zoonoses, meningitis, acute respiratory syndrome, diarrheal disease, etc., are still on their way. In addition, national and regional cholera and influenza epidemics occur every now and then, and require special attention[5] Also, Iran is on the verge of controlling measles and eliminating malaria.[6] Regulations that mandate disease reporting in Iran was passed in 1941, and the most recent amendment was made in 1997. However, underreporting, especially in the private sector, remains a challenge for the health information system in Iran[7] and this issue has been underlined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as well.[5] As usual, Iran's surveillance system is rather passive except for some programs such as the malaria active case finding.[5] Since passive disease surveillance system is greatly dependent upon physicians’ reports,[8] their participation in notification, especially in urban areas, constitute one of the most important sources of information in health systems. This study was conducted to identify barriers and potential solutions of improving disease reporting by physicians in the private sector. The result of this qualitative study is applicable for big cities (particularly in developing countries) which the private sector is one of the main sources of disease diagnosis and notification.

METHODS

This study was conducted as a qualitative study. Data was collected through focus group discussions and semi-structured interviews with private sector physicians, managers, and experts in the field of surveillance systems.

Private sector physicians were purposefully selected based on their specialty and field of activity among general practitioners, pediatricians, internists, and infectious disease specialists. The physicians, who agreed to be interviewed, were approached at their workplace. During the interview, we asked their views on the overall situation of disease reporting, the weaknesses of the disease notification system, and measures to improve reporting of notifiable disease and enhance the interaction between the surveillance system and physicians in the private sector. We reached data saturation after seven interviews. Data was recorded using a voice recorder and taking notes.

To assess the views of managers in the surveillance system (disease managers at provincial and regional health directorates), 4 focused group discussions were held and 16 disease managers from different provinces attended them. There was one moderator and one note taker present at each discussion session. Each session was 70 min on average.

To hear the views and opinions of experts, we interviewed 2 experienced managers, who had more than 10 years experience on the national level, and one researcher who had conducted researches around the legal aspect of surveillance systems.

Recorded voices (about 12 h) were transcribed verbatim. Codes were extracted from the transcriptions using the open code software topic, and analyses were done using the thematic framework.

Participants were asked for permission to record interviews and discussion sessions, and they were reminded of their rights to stop the recording at any time.

RESULTS

The most important factors affecting physicians’ tendency to report notifiable conditions were summarized in the 6 categories with 18 sub categories. The categories were consisted of ‘Infrastructure and legal issues’, ‘The importance of reporting from the views of stakeholders’, ‘Workflow processes’, ‘Motivation and attitude of the private sector’, ‘Human resources in the health sector’ and ‘Knowledge and awareness about disease reporting’. The following sections comprise the categories and sub categories accompany with some of participants quotes (italics). The group, the quote belongs to is noted in parenthesis at the end of each quote. These groups shall be referred to as experts (the national experienced managers and the researcher), managers (disease managers at the provincial and regional levels), and physicians (physicians working in the private sector).

Infrastructure and legal issues

Disease reporting process is defective

Participating physicians found the current processes of disease reporting is defective and ineffective. Most of them believed the process in the surveillance system lacked many attributes on the government side, especially where reporting disease was concerned.

“Reporting is important for physicians too, but there is no routine, organized system to get things right. Unfortunately, the system is not well established. It is not something that would alert us and get the information from us systematically” (physician).

Legal aspects

Some of managers and the experts thought lack of a proper law had created problems for the surveillance system.

“For instance, there was a violating physician whom we have reprimanded several times orally, and in writing. Finally, we referred the case to the judiciary system, and were settled for an unbelievably low fine; so low we do better not mention it. The fine is paid, and the physician walks passed us with a smile” (manager).

“There must be some law for reporting. When there is law, no one can claim they did not know … of course note that law refers to something passed in the senate, not something a minister might say” (expert).

Some diseases are too rare to be notifiable in some place

Some physicians and managers believed prioritizing notifiable disease, or prioritizing according to time and place can increase reporting.

“No matter how badly physicians get along with the surveillance system (may be they have bad attitude to the surveillance system), but they will always report a case of plague. They (governmental agents) keep asking: You have got any plague? You have got any yellow fever? (means that governmental agents do not care about physician perception of disease)” (physician).

Ethical issues

Another issue that managers noted is the ethical aspects of reporting disease.

“In our province, I remember they used to report zero cases many years ago. When we told them we did not need names, the stats went up to 12 to 13 thousand. Patients’ trust in their physicians must be considered” (manager).

In contrast, none of the physicians mentioned the issue of law in reporting.

The importance of disease reporting from the views of stakeholders

Surveillance is not a priority in the health system

Both groups of physicians in the private sector and managers working within the service believed the issue of surveillance in reality was not a priority in the health system and did not receive enough attention.

“We do not care who is in the Ministry of Health, and what they want. They (themselves) do not find reporting an important matter” (physician)

“There is no follow-up. No one comes; not even once a year. So, it would be a lot to ask me to care.” (physician)

“Whenever there is a financial pressure in the province, the first place they close down is the afternoon hours (follow-ups after working hours) with the reporting office. The view on this issue is very weak” (manager).

Lack of cooperation between health sectors in county level

Another issue mentioned by managers was lack of cooperation in clinical care section with the surveillance system in public health sector in county level. They thought that indicate the clinical and cure managers are not aware about importance of disease surveillance.

“The patient has been hospitalized for a week, and I have received no report yet. When I inquire, the head of the hospital sends a message that we should go over there. They say it is none of their business, and consider themselves apart. They even enjoy having a gap. The wall of mistrust exists between health and treatment, not between health and the private sector” (manager).

Workflow processes

Performing programs for notification has several deficiencies

Although most managers believed the surveillance system is acceptably responsive, for some conditions and disease, but they thought lack of a proper attention and functional supports are one of the most barriers for notification in private sector. This issue mentioned by participating experts as well. They agreed that the surveillance system did not receive sufficient support for improvement. They blamed financial concerns in health system.

“I think the framework for the surveillance system in Iran has been designed well, because it fits with what is happening in the world and we copy the pattern … We, also interact with the WHO a lot. This is what is been done before us too… we use their help whenever there is a problem … So, we have no problems with the framework, its structure or design. The problematic part is the execution …” (manager).

Programs are inconstant

Most managers and physician believed that forces and interventions were transitory, and existed only for a few certain diseases.

“Necessary measures are sometimes taken, but it is done transiently, and the new program comes to a sudden halt. Even when we send the stats, they say they do not need it anymore” (manager).

Need for specify notification process in private sector

Study participants, especially physicians, complained that there was no defined process for reporting. Participants emphasized that the process should facilitate reporting for physicians as much as possible.

“I do not know how I report, there are some guides in public clinics, but I cannot use them (in private sector), first, the person responsible for health affairs in a certain area should be known. His number and address must be declared. I need to know who I have to correspond with, and have an easy way of accessing that person…” (physician).

Motivation and attitude of physicians in the private sector

Lack of incentives and individual gain for physicians

Most physicians blamed their inactivity in reporting on the negligence in the public section. On the other hand, managers and experts, although admitted to shortcomings in the public sector, pointed out that creating financial incentives and personal gain for physicians can increase their tendency to report disease.

“A simple commendation is useless. Practicing physicians are not doing well (financially). There is no support, and the government expects them to do some extra work in addition to what they do” (manager).

Perceptions in private physicians

Managers insisted that the major reasons of physicians’ lack of active participation in reporting notifiable disease were negative perceptions to public sector in private physicians.

“They think a physicians’ duty is to treat the patient in the clinic… that is what they look at. They do not see the health community and how a disease report can help the whole society. Unfortunately, physicians in the private sector, find this (reporting) as useless stats (useless)” (manager).

“The importance of the issue is not recognized in the private sector at all. They think someone has to come and put some paper in front of them, and they just have to stamp it and tell them to take it…” (manager).

What happen to the data I reported? (Lack of feedback)

Most managers believed that feedback could increase physicians’ willingness to report. This matter was not very clear for physicians, and they thought its importance lay in confirmation of the diagnosis.

“We need to share our information with physicians. Then they can make use of their own work. This way they will feel useful in improving the health status in the country” (expert).

“They (physicians) have asked us many times: What is happened to all those reports? What did you do with all the reports we submitted last year?” (manager).

“I think, physicians are eager to know if they have made the right diagnosis or not, and what they need to do for next patients. This can also improve the relationship between physicians, patients, and health care system” (physician).

Physicians don’t have enough time to participation

Some managers believed physicians spent too little time on filling out forms and did suggestions.

“In our country, the average times that physicians spend on their patient are much lower than the standards. Many of the problems in the reporting system arise from primary misdiagnoses.” (manager)

“If secretaries are aware and ask the physician … or reception … the receptionist … or anyone else who is there” (manager).

Some physician believed too and they had suggestions too:

“Reporting will work successfully when it is somehow privatized like all other things in the educational system in Iran. It should have private subdivisions. They can even use NGOs” (physician).

However, several of physicians thought reporting does not take their time if other condition established well.

“I have no problem (with reporting), if I see (diagnose) a (notifiable) patient I filling a form for him too. It is not taking my time…” (physician).

Human resources in the health sector

Peripheral personnel in health system are not well enough educated

According to most managers, lack of skilled personnel in the peripheral public sector was an important barrier. They suggested training current staff, appropriate for the assigned responsibilities. Experts also pointed out shortage in human resource; they thought new skilled staff in the health sector is needed.

“I begged a hundred people before I could get a volunteer to come. Considering the limited resources and budget, I had to use staff with very low education” (manager).

“With this covered population, we need more human resources, and the population is growing, so we need 5 times more than this. The heads of organization would not allow us to hire more people; because of resource limitations…” (expert).

Attitudes and manners of whose being touch with private physician directly

Participating physicians pointed out the attitudes and manners of the person or people who presented themselves to collect reports from physicians. Similarly, managers agreed that the attitude of the person collecting reports from physicians was an important factor.

“The collecting person does not dedicate any time. They say: Sign it, I got to go. They say: It is beyond the scope of our duties. Now, they pay overtime which is not worth the time, they have to spend” (physician).

“That is, they do not do. Either the overtime pay is little, or we did not have the right person, or we give it to someone who already has 4 or 5 things to do, or they do not treat physicians well.” (manager).

Physicians’ knowledge about notification

Physician are not informed about the surveillance system and reporting

One of the most important issues discussed by participating managers was that physician were not informed of the basics of the surveillance system and reporting.

“We need to bring their (physicians) information to a certain level. Many of those who work in the treatment division are not familiar with the surveillance system. They do not know what it is … which disease they should report…” (manager).

“Physicians in larger cities are generally not aware of what they need to report. Even if they do, they do not know where they should report to.” (expert).

Deficiency in continuing medical education programs

Although physicians were aware of their insufficient information about reporting disease, they found the public sector of the surveillance system responsible for it. All groups pointed out the need for continuing medical education programs.

“There is no distribution of information to see what we are doing. Do not blame the lack of cooperation on physicians… I have no problem (with reporting), provided that they (health system) tell us what to be report.” (physician).

“I think it is our (surveillance system) fault because we do not give them enough information. They do not know our requests” (expert).

Qualitative and quantitative shortcomings in university courses for medical student

A number of managers stated there were qualitative and quantitative shortcomings in university courses for medical student, as far as the surveillance system was concerned, and believed they attributed to physicians’ lack of knowledge and interest in reporting.

“I think, this issue should be noted when their studying as medical students, and we should make use of the courses. It can be fit in their training, where they will understand it well” (manager).

“Medical students are sent to work at health centers for a month. They are involved for a month in that particular year. When they are done, they are not informed of new programs” (expert).

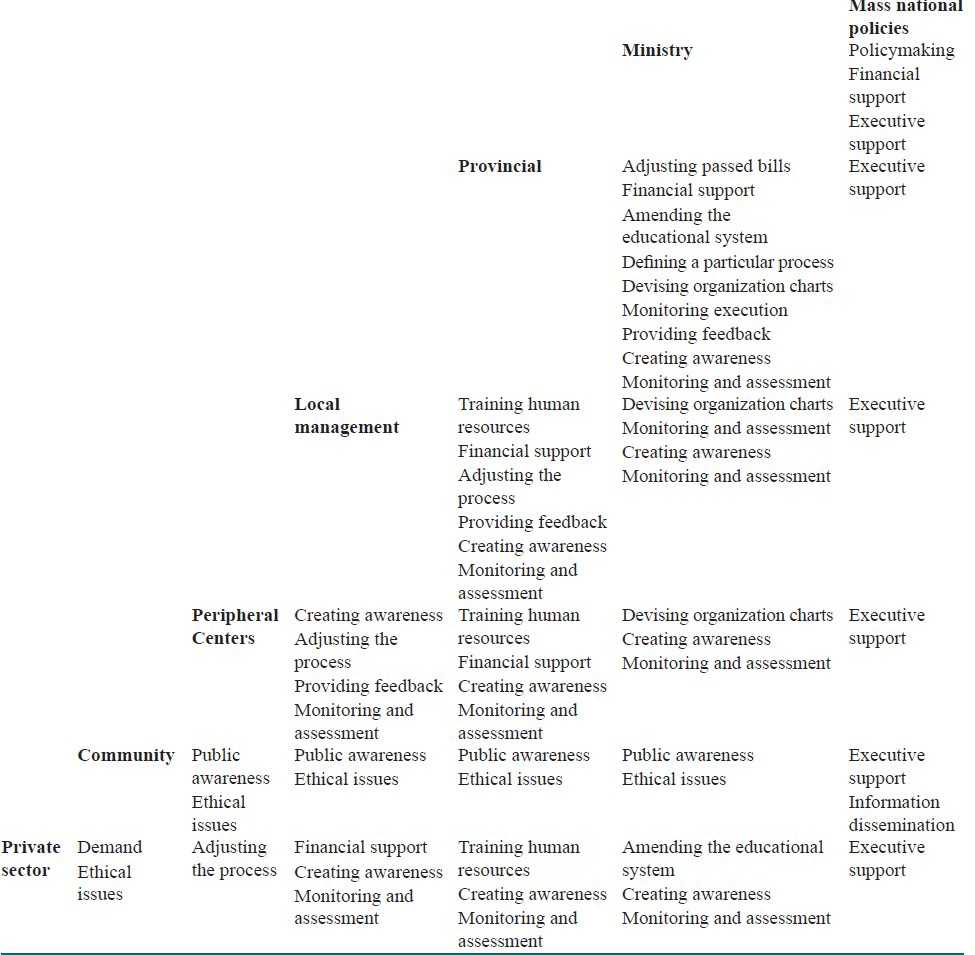

In addition to this categorization, to use the identified determinants as a basis for intervention programs, we analyzed the themes according to the level of execution and performance. Table 1 contains the themes extracted from this study. This table is constructed with the assumption that each level can intervene in all lower levels, but cannot run intervention programs in those in the same level or above level.

Table 1.

Crosstab of the classification of themes according to the intervening level (column header) and the intervention level (row header)

DISCUSSION

The overall process of data circulation in the surveillance system in Iran lacks acceptable efficiency, despite having appropriate mechanisms for smaller cities and rural areas. On the other hand, lack of the same infrastructure in larger cities, complicated matters. Thus, information based on disease reporting is rendered unreliable. Also, private practices are less in touch with organizations in charge of the surveillance system, and this decreases private physicians’ motivation for reporting disease, even when they have a positive attitude.

In this study, we tried to include interviewees from all levels of the health care network. We put together the views of physicians in the private sector, managers at provincial and regional and experts who have accomplished valuable managerial tasks in national level or have done extensive research in this field; this provided a complete understanding about determinants of reporting notifiable disease in the country. Considering the levels within the surveillance system defined,[9] we fit interventions in seven levels which are presented in Table 1 and discussed below. In this section quotes “ ”, denote the main themes of the study result.

National policymaking

In this level, which is generally beyond the capacities of health organizations, in addition to “monetary and budgety” problems, the crucial issue of “legislative and executive support” faces the surveillance system. A proper law is necessary for most intervention programs concerning reporting and can directly affect other factors related to it.[10] The law that mandates disease reporting in Iran was passed in 1941 and the list of notifiable conditions and reporting procedures were edited in the 1997 amendment,[11] but its enforcement has not received attention yet. In fact, execution the law is an issue that requires extrasectoral cooperation with executive organizations for all levels of the surveillance system. “Public awareness” is another issue that requires activities (such public media) other than those affiliated with the Ministry of Health. Perry et al.[9] have stated the effect of public awareness on surveillance system as well.

The ministry of health

The main issue in this level is the “notification process”. In addition to support from highest executive and judicial levels, various aspects of the disease surveillance system call for “constant support and management”. The participants of this study pointed out shortcomings in the notification process. Managers and physicians’ views imply that the notification process in the private sector needs to be not only comprehensive and acceptable, but also flexible so that it can be adjusted to different working conditions of physicians. The process requires certain characteristics to increase the willingness of stakeholders to perform notification, e.g., if the notification process involves gaining particular monetary or professional privileges, they will actively attempt to resolve obstacles. The notification process has been a matter of emphasis by others.[12] In another study in Iran, one of the most important suggestions to resolve the problem with noncompliant physicians was to facilitate the notification process.[11] Defining the national reporting process, in which the responsibilities and rights of all stakeholders is clearly stated and has sensitive, comparable and measurable indicators, is generally in the capacity of the Ministry of Health. “Setting a special organization chart” and “adjusting curricula for medical students” lie in this domain as well.

As the responsible body for national health programs, the Ministry of Health needs to “supervise” and “disseminate information” to all levels of the surveillance system. Publishing national reports, can serve as information dissemination, as well as a form of feedback. Many studies have assessed various reporting methods which can be classified in this level.[13,14,15,16,17,18,19]

Provincial, regional management and peripheral level

As stated in Table 1, in charge of executive activities of the surveillance system, the provincial level is monitoring the regional (local management) and district level (peripheral centers). The themes of “training human resources”, “executive and financial support”, “education”, “knowledge and awareness”, which have been defined for the two recent levels, are almost the same. However, in Iran the levels of their activities differ. In fact, there is a relative independence at the regional level to prioritize regional programs and personnel assignments, while such independence is not in the peripheral level. Implement national programs, or designing an interventional program to increase local physicians’ cooperation is dependant upon “awareness and interest of local directors” as well. Giving the necessary training to local directors and managers can affect their decisions and internal budget allocation.

One of physicians’ main concerns was how the information contained in reports was used. “Appropriate and timely feedback” is an effective intervention,[11,12,20,21,22,23,24] especially in regional level. The “insufficient skilled personnel” in this level are mentioned as a reason for failure to provide appropriate feedback for physicians.[4] To achieve its goals, the surveillance system requires appropriate and sufficient human capital. Training skilled human resources in the field of disease notification is one of the determinants of notification.[4,24] Such resources can greatly improve notification in different levels, especially regional level. The realization of human capital for the surveillance system goes back to the educational programs in universities. The “refresher courses” for health personnel can also be effective in providing the necessary human capital. Concerning human capital, another finding of our study concerned people who were in charge of collecting reports from physicians (peripheral level). Participating physicians commonly complained of “collecting person's lack of interest” in compiling information and their negative attitude towards physicians’ efforts to report disease. This attitude was mostly due to “low education” and lack of “supervision from higher levels”. According to our study, this group can play an important role in motivating physicians to notify disease because they come in direct contact with them.

Community

Depending on the culture and values of the society, the perception of the community and “ethics on reporting disease” can vary. Many physicians stress “patients’ personal rights”, they believe reporting disease is a breach of patient rights and can weaken the “physician-patient relationship”. In the study in Taiwan, 33% of participating physicians thought ethical issues were the most important cause for not reporting disease.[12] In our study, some mangers pointed out this issue as a barrier to reporting disease, especially in small areas and disease with social stigma, but participating physicians did not mention the ethical concern as a barrier for notification. This difference can be due to the type of social relationships between physicians and their patients in larger cities.

Physicians

The participants of our study, whether physician, manager, or expert, admitted to the many shortcomings regarding physicians’ knowledge about notifiable conditions and the reporting process, this was especially true about those in the private sector. Many studies on disease notification have focused on different aspects of “knowledge”, “attitude”, and actions of physicians.[8,10,11,12,20,21,22,23,24] Some have evaluated one or more interventions in improving the notification process in the physicians’ level.[14,16,17,25] Nader and Askarian[11] have shown that Iranian physicians’ knowledge about disease notification and motivation to report disease is very low. In their study, 83% of the physicians did not know the organization in charge of receiving reports, and only 16% had its contact numbers. According to the study by Tan and colleagues (2009), physicians in the public sector have better knowledge of disease reporting than those in the private sector. Such lack of awareness has been frequently mentioned in reports from other parts of the world as well.[12,13,14,16,17,22,23,24] According to these results, we recommend that further research on the evaluation of various interventions to improve physician awareness be given higher priority.

In terms of physicians’ attitude, although most managers in our study believed that physicians do not consider disease reporting a professional duty, most physicians disagreed. The issue that “disease reporting is outside the scope of physicians’ responsibilities” and its solutions have been mentioned in other studies as well.[11,12,14,16]

CONCLUSIONS

It seems that the key option among many solutions to improve disease reporting in quality and quantity is establishing an appropriate notification process. This process should support its utmost performance and sustainability by offering privileges to various stakeholders. Incentives, privileges, and a positive perception of stakeholders would prompt them to prioritize disease reporting and participate actively in the process. This will build the grounds for services that would increase awareness and remove many other barriers of disease reporting mentioned in this study, as well as other reports. In other words, if physicians see their disease reports as a good to be purchased by the disease surveillance system, they will make efforts to improve the quality and quality of their goods. In addition, need for proper monitoring to improve the efficiency of the process cannot be ignored. All solutions which can improve the quality and quantity of information, especially in larger cities and the private sector, when they are implemented along with a proper and feasible law to determine the jurisdiction, rights, liabilities, and incentives of stakeholders.

Footnotes

Source of Support: All authors of this manuscript declear that they don’t have any conflict of interest. This study was a part of the thesis of the first author (AA) and by this was financially supported by Tehran University of Medical Sciences

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Thacker SB, Birkhead GS. Surveillance. In: Gregg MB, editor. Field Epidemiology. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Naghavi M, Abolhassani F, Pourmalek F, Lakeh M, Jafari N, Vaseghi S, et al. The burden of disease and injury in Iran 2003. Popul Health Metr. 2009;15(7):9. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-7-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berkelman RL, Bryan RT, Osterholm MT, LeDuc JW, Hughes JM. Infectious disease surveillance: A crumbling foundation. Science. 1994;264:368–70. doi: 10.1126/science.8153621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thacker SB, Choi K, Brachman PS. The surveillance of infectious diseases. Jama. 1983;249:1181–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sadrizadeh B. Malaria in the world, in the eastern Mediterranean region and in Iran: Review article. WHO/EMRO Report. 2001;1:13. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaafar T, Moshni E, Lievano F. The challenge of achieving measles elimination in the Eastern Mediterranean Region by 2010. J Infect Dis. 2003;187(Suppl 1):S164–71. doi: 10.1086/368035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Majdzadeh R, Pourmalek F. A conditional probability approach to surveillance system sensitivity assessment. Public Health. 2008;122:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gauci C, Gilles H, O’Brien S, Mamo J, Calleja N. General practitioners role in the notification of communicable diseases study in Malta. Euro Surveill. 2007;12:E5–6. doi: 10.2807/esm.12.11.00745-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perry HN, McDonnell SM, Alemu W, Nsubuga P, Chungong S, Otten MW, Jr, et al. Planning an integrated disease surveillance and response system: A matrix of skills and activities. BMC Med. 2007;5:24. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-5-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Voss S. How much do doctors know about the notification of infectious diseases? BMJ. 1992;304:755. doi: 10.1136/bmj.304.6829.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nader F, Askarian M. How do Iranian physicians report notifiable diseases? The first report from Iran. Am J Infect Control. 2009;37:500–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tan HF, Yeh CY, Chang HW, Chang CK, Tseng HF. Private doctors’ practices, knowledge, and attitude to reporting of communicable diseases: A national survey in Taiwan. BMC Infect Dis. 2009;9:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-9-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trepka MJ, Zhang G, Leguen F. An intervention to improve notifiable disease reporting using ambulatory clinics. Epidemiol Infect. 2008;137:22–9. doi: 10.1017/S0950268808000721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huaman MA, Araujo-Castillo RV, Soto G, Neyra JM, Quispe JA, Fernandez MF, et al. Impact of two interventions on timeliness and data quality of an electronic disease surveillance system in a resource limited setting (Peru): A prospective evaluation. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2009;9:16. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-9-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simple Online Methods Increase Physician Disease Reporting [database on the Internet] 2010. [Last cited on 2010 Apr 14]. Available from: http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/01/080114142307.htm .

- 16.Weiss BP, Strassburg MA, Fannin SL. Improving disease reporting in Los Angeles County: Trial and results. Public Health Rep. 1988;103:415–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.John TJ, Rajappan K, Arjunan KK. Communicable diseases monitored by disease surveillance in Kottayam district, Kerala state, India. Indian J Med Res. 2004;120:86–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ward M, Brandsema P, Van Straten E, Bosman A. Electronic reporting improves timeliness and completeness of infectious disease notification: The Netherlands, 2003. Euro Surveill. 2005;10:27–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allen CJ, Ferson MJ. Notification of infectious diseases by general practitioners: A quantitative and qualitative study. Med J Aust. 2000;172:325–8. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2000.tb123979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Figueiras A, Lado E, Fernandez S, Hervada X. Influence of physicians’ attitudes on under-notifying infectious diseases: A longitudinal study. Public Health. 2004;118:521–6. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2003.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ofili AN, Ugwu EN, Ziregbe A, Richards R, Salami S. Knowledge of disease notification among doctors in government hospitals in Benin City, Edo State, Nigeria. Public Health. 2003;117:214–7. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3506(02)00021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Al-Laham H, Khoury R, Bashour H. Reasons for underreporting of notifiable diseases by Syrian paediatricians. East Mediterr Health J. 2001;7:590–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.AbdoolKarim SS, Dilraj A. Reasons for under-reporting of notifiable conditions. S Afr Med J. 1996;86:834–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bawa SB, Umar US. The functional status of disease surveillance and notification system at the local government level in Yobe State, Nigeria. Niger J Clin Pract. 2009;12:74–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seneviratne SL, Gunatilake SB, De Silva HJ. Reporting notifiable diseases: Methods for improvement, attitudes and community outcome. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1997;91:135–7. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(97)90199-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]