Abstract

Objectives:

Helicobacter pylori infection may be associated with low iron stores and iron deficiency anemia. Eradication of infection by the standard 10-day therapy (a proton pump inhibitor [PPI], clarithromycin and amoxicillin; each given orally, twice daily) is decreasing. The sequential 10-day therapy (a PPI and amoxicillin; each given orally twice daily for 5 days; followed by a PPI, clarithromycin and tinidazole; each given orally twice daily for another 5 days) may achieve higher eradication rates. This study was designed to investigate, which eradication regimen; sequential or standard; more effectively improves the associated iron status and iron deficiency in children.

Materials and Methods:

Children (12-15 years) with H. pylori active infection (positive H. pylori immunoglobulin G and urea breath test [UBT]) were subjected to measurement of serum ferritin and then randomized into two groups to receive standard and sequential eradication therapy. Six weeks after completing therapy, UBT was performed to check eradication and serum ferritin was measured to estimate affection by therapy. Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS, IBM, NY, USA) was used for analysis.

Results:

H. pylori eradication rates of sequential versus standard therapy were non-significantly different. Serum ferritin non-significantly differed between the two therapy groups and in the same group before and after treatment.

Conclusions:

There is no significant difference in H. pylori eradication rates between sequential and standard therapies in children. Moreover, no significant relationship was found between eradication therapy and serum ferritin. Further studies enrolling more markers of iron deficiency are required to precisely assess this relationship.

KEY WORDS: Children, eradication, Helicobacter pylori, serum ferritin

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori infection is the main known cause of gastritis, gastroduodenal ulcer and gastric cancer. After 30 years of experience in H. pylori treatment, however, the ideal regimen to treat this infection eludes us.[1] H. pylori antibodies are detected in blood few weeks after infection (active infection), in case of past exposure or after antimicrobial eradication. Moreover, individuals vary considerably in their antibody responses to H. pylori antigens.[2] Therefore, the urea breath test (UBT) is considered to be a “gold standard” technique for detection of H. pylori infection. When using 37 kBq (1 μCi) of 14C-urea for the 14C-UBT, the patient is not exposed to more radiation than is acquired from the natural environment in 1 day as almost all the ingested radioactivity is excreted from the body (urine and breath) within 72-120 h. Thus, 14C-UBT use in children is justified without any fear of “radiation phobia.”[3] The eradication rate of H. pylori by the standard 10-day triple therapy (a proton pump inhibitor [PPI], clarithromycin and amoxicillin; each given orally twice daily) is decreasing due to antibiotic resistance, mainly to clarithromycin.[4] In contrast, the sequential 10-day therapy (a PPI and amoxicillin; each given orally twice daily for 5 days; followed by a PPI, clarithromycin and tinidazole; each given orally twice daily for another 5 days) is promising and achieves higher eradication rates.[5]

H. pylori infection has been found to be associated with low iron stores[6] and iron deficiency anemia.[7] In iron deficiency anemic H. pylori-infected patients, eradication of the infection could be effective in improving anemia and iron status. The difference from baseline to endpoint of hemoglobin, serum iron and serum ferritin was significantly different between anti H. pylori treatment plus oral iron and oral iron alone.[8] Serum ferritin level is positively correlated with the total iron stores in the absence of inflammation where low serum ferritin reflects depleted stores.[9] This study was therefore designed to investigate, which H. pylori eradication regimen; sequential or standard; more effectively improves the associated iron status and iron deficiency in children.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee and was performed in accordance with the international guidelines of medical research. The study was conducted on recently-diagnosed H. pylori positive; otherwise apparently healthy; intermediate school male children (12- 15 years). They were tested for H. pylori immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody and those positives were subjected to UBT to detect active infection. Children who consumed acid inhibitors, bismuth compounds or antibiotics during the previous 4 weeks or those with known allergy to antibiotics were excluded. Written informed consent was obtained from fathers of all subjects. Serum ferritin was measured for 18 boys, then they were randomized 1:1 into two groups (n = 9). One group received the standard eradication therapy consisting of rabeprazole 20 mg, clarithromycin 250 mg and amoxicillin 500 mg each administered orally twice daily for 10 days. The second group received the sequential eradication therapy consisting of rabeprazole 20 mg and amoxicillin 500 mg for 5 days, followed by rabeprazole 20 mg clarithromycin 250 mg and tinidazole 500 mg for another 5 days, each administered orally twice daily. Boxes containing a number of these tablets sufficient for the treatment duration were provided to each child. Patient compliance was evaluated by counting the number of tablets returned.[10] Six weeks after completion of eradication therapy, H. pylori status was assessed using UBT and serum ferritin was measured to estimate effects of eradication therapy on it. The preparations used were: Rabeprazole (Pariet, 20-40 mg, Janssen-Cilag, Eisai Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), clarithromycin (claridar, 15-30 mg/kg) and amoxicillin (amoxydar forte 20-40 mg/kg), Dar Al Dawa, Na’ur, Jordan and tinidazole (Fasign, 50-75 mg/kg, Pfizer Ltd., Co., Tadworth, Surrey, UK).

Measurement of Serum H. pylori IgG

Serum H. pylori IgG level was measured by the enzyme linked fluorescent assay (ELFA) test with BioMérieux HPY-VIDAS system (Marcy l’Etoile, France). Three milliliter of blood was obtained from each subject and the sera were stored at -80°C until analysis. The assay principle combines a two-step enzyme immunoassay sandwich method with a final fluorescent detection (ELFA). It has a sensitivity of 98.10%, specificity of 90.82% and was interpreted as follows: <0.75 is negative, ≥0.75 to <1.00 is equivocal and ≥1.00 is positive.[11]

UBT

After overnight fast, boys swallowed 37 kBq (1 μCi) of encapsulated 14C urea/citric acid solution (Helicap™, Kibion AB, Uppsala, Sweden) with 25 ml water. Breath samples were collected into Heliprobe® breath cards within 10 min. Subjects exhaled into the breath card until its color indicator changed from orange to yellow. The breath samples were measured using the Heliprobe Analyzer® and the activity was measured for 240 s. Values <25 counts per minute (cpm) were defined as Heliprobe 0 (not infected), 25-50 cpm as Heliprobe 1 (equivocal) and >50 cpm as Heliprobe 2 (infected).[12]

Measurement of Serum Ferritin

Serum ferritin was quantitatively measured using the architect ferritin reagent kit (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL, USA), which combines a two-step chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay technology with flexible assay protocols, referred to as Chemiflex. In the first step, sample and anti-ferritin coated paramagnetic microparticles were combined. Ferritin present in the sample binds to the anti-ferritin coated microparticles. After washing, anti-ferritin acridinium labeled conjugate is added in the second step. Pre-trigger and trigger solutions are then added to the reaction mixture; the resulting chemiluminescent reaction is measured as relative light units (RLUs). A direct relationship exists between the amount of ferritin in the sample and the RLUs detected by the Architect optical system.[13] Normal range of serum ferritin in children aged 12-15 years old is 20-200 ng/ml.[14]

Statistical Analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 18, IBM Corp., New York, USA) program was used. Analysis of data was performed on an on-treatment analysis. The Chi-square (χ2) test was used for comparison of nominal data. Numeric values were given as mean values ± standard error of mean analysis was performed for paired data using two-tailed Student's t-test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

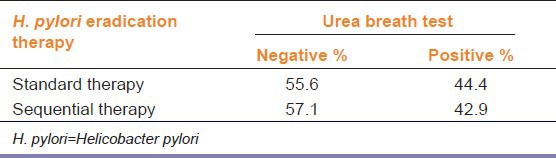

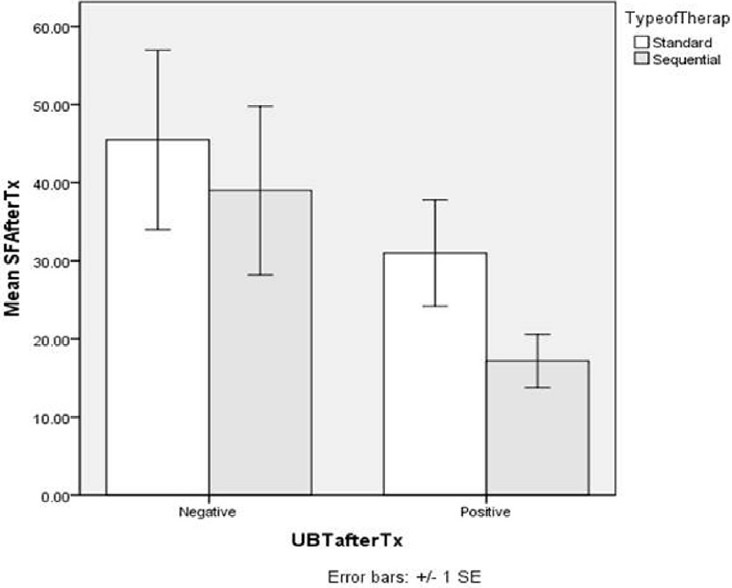

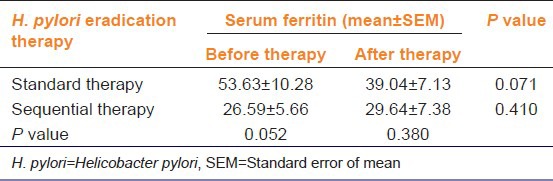

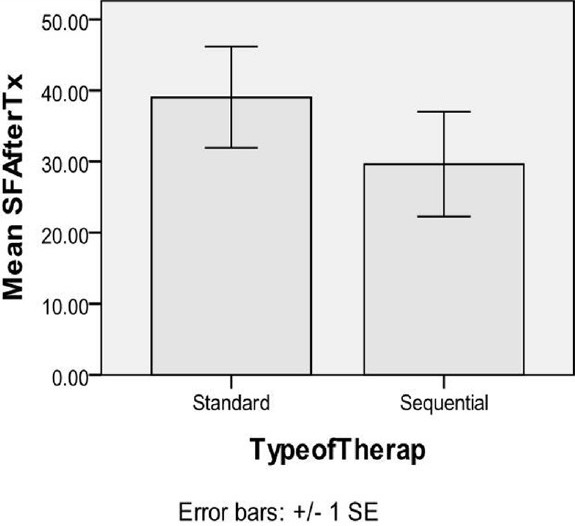

In the current study, 18 H. pylori-positive children were enrolled. Two boys from the sequential therapy group were poorly compliant, considered drop-outs and excluded. 16 were included in the on-treatment analysis, with nine and seven in the standard and sequential groups, respectively. Six weeks after completion of therapy, H. pylori test on 14C-UBT was negative in 5 (55.6%) of nine patients in the standard and in 4 (57.1%) of 7 patients in the sequential groups. This eradication rate although slightly higher with sequential therapy, it is non-significant (P = 0.949) [Table 1]. To exclude any direct effects of drugs (i.e., not through H. pylori eradication) on serum ferritin, it was measured post-treatment for all children (i.e., whether UBT was negative or positive) and non-significant differences were found [Figure 1]. As shown in Table 2, serum ferritin in the same group (standard or sequential), non-significantly differed before and after therapy. Between the two groups, serum ferritin before therapy was quite different, however that difference was non-significant. After therapy, the difference between both groups was also non-significant [Figure 2].

Table 1.

Effect of H. pylori eradication therapy, standard and sequential (n=9 and 7 respectively), on urea breath test (expressed as percentages of the total number of cases)

Figure 1.

Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy, standard and sequential (n=9 and 7 respectively), on mean serum ferritin after treatment (mean SF after Tx) in case of success and failure of H. pylori eradication (negative and positive urea breath test respectively)

Table 2.

Effect of H. pylori eradication therapy, standard and sequential (n=9 and 7 respectively), on serum ferritin (ng/ml)

Figure 2.

Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy, standard and sequential (n=9 and 7 respectively), on mean serum ferritin after treatment (mean SF after Tx) irrespective of H. pylori eradication

Discussion

The UBT is a highly accurate test with sensitivity and specificity over 95%. It is used to diagnose active H. pylori infection in IgG-positive subjects and to detect successful eradication after therapy.[15] The current study showed that H. pylori eradication rate although slightly higher with sequential therapy, it was non-significant compared with that of standard therapy. Serum ferritin non-significantly differed between the two therapy groups and in the same therapy group before and after treatment.

In a systematic review, it was mentioned that that while the majority of the randomized clinical trials (RCTs) have shown superior eradication rates with sequential therapy, the largest RCT from Latin America did not find a significant difference between the standard and sequential regimens. It was concluded that sequential therapy has good efficacy; however, further trials other than those from Asia and Italy are required to assess its superiority over existing regimens before recommending it as the first line of treatment for H. pylori infection.[16] In children with H. pylori infection, sequential therapy resulted in a higher eradication rate than standard therapy although the difference was of borderline statistical significance.[17] In an Italian study, eradication rate was found to be significantly greater with sequential than standard treatment; however, this may be due to the additional antibiotic (tinidazole) in sequential therapy. Incomplete follow-up in this study makes results non-generalizable to other countries.[18]

H. pylori infection was not significantly related to low serum ferritin or iron deficiency anemia.[19,20] Moreover, H. pylori infection had a non-significant negative effect on serum ferritin in children and no significant difference in prevalence of iron deficiency was found between H. pylori-positive and negative groups.[14] However, in another study, serum ferritin was significantly lower and iron deficiency was significantly higher in H. pylori-seropositive than in seronegative children.[21] The benefit of H. pylori eradiation for iron deficiency anemia has been extensively studied, but data are still equivocal. In a double-blind randomized trial among non-iron-deficient asymptomatic H. pylori-infected children living in the contiguous United States, no effect of H. pylori eradication regarding changes in iron stores was found. However, those who had their infection eradicated by the quadruple sequential eradication at follow-up had a significantly larger increase in serum ferritin from baseline.[22] In contrast, H. pylori infection was found to be correlated with lower serum ferritin and iron deficiency. After eradication, serum ferritin increased and approximately half of persons resolved their iron deficiency.[23] This controversy may be explained by a seroepidemiologic study in school children in Pondicherry in India that mentioned that response to anti-H. pylori therapy in children with iron deficiency could establish the causal relationship between iron deficiency anemia and H. pylori infection only after other causes of iron deficiency such as hookworm infestation and poor iron intake have been identified and treated.[24]

A limitation of the present study is that it was conducted on a relatively small number of male children. Thus, a larger study in different pediatric age and gender groups is recommended.

Conclusion

H. pylori eradication rates in children were non-significantly different in sequential versus standard therapy. Moreover, serum ferritin was non-significantly different between both therapies and in the same therapy group before and after treatment. Further studies enrolling more markers of iron deficiency are required to precisely assess the relationship between H. pylori eradication therapy and iron status and to determine which regimen, sequential or standard, is considered superior in this respect.

Footnotes

Source of Support: This project was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research, (DSR), King Abdulaziz University (KAU), Jeddah, under grant number (332/140/1431). The authors, therefore, acknowledge with thanks DSR for technical and financial support

Conflict of Interest: No

References

- 1.Vakil N. H. pylori treatment: New wine in old bottles? Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:26–30. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Logan RP, Walker MM. ABC of the upper gastrointestinal tract: Epidemiology and diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. BMJ. 2001;323:920–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7318.920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pathak CM, Kaur B, Khanduja KL. 14C-urea breath test is safe for pediatric patients. Nucl Med Commun. 2010;31:830–5. doi: 10.1097/MNM.0b013e32833c3647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cambau E, Allerheiligen V, Coulon C, Corbel C, Lascols C, Deforges L, et al. Evaluation of a new test, genotype HelicoDR, for molecular detection of antibiotic resistance in Helicobacter pylori. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:3600–7. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00744-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chey WD, Wong BC. Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1808–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berg G, Bode G, Blettner M, Boeing H, Brenner H. Helicobacter pylori infection and serum ferritin: A population-based study among 1806 adults in Germany. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1014–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cardenas VM, Mulla ZD, Ortiz M, Graham DY. Iron deficiency and Helicobacter pylori infection in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:127–34. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yuan W, Li Yumin, Yang Kehu, Ma Bin, Guan Quanlin, Wang D, et al. Iron deficiency anemia in Helicobacter pylori infection: Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:665–76. doi: 10.3109/00365521003663670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Geneva: Vitamin and Mineral Nutrition Information System; 2011. [Accessed June 1, 2013]. Serum ferritin concentrations for the assessment of iron status and iron deficiency in populations. WHO/NMH/NHD/MNM/11.2. Available from: http://www.who.int/vmnis/indicators/serum_ferritin.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 10.Du YQ, Su T, Fan JG, Lu YX, Zheng P, Li XH, et al. Adjuvant probiotics improve the eradication effect of triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:6302–7. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i43.6302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhubi B, Baruti-Gafurri Z, Mekaj Y, Zhubi M, Merovci1 I, Bunjaku I, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection according to ABO blood group among blood donors in Kosovo. J Health Sci. 2011;1:83–9. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hegedus O, Rydén J, Rehnberg AS, Nilsson S, Hellström PM. Validated accuracy of a novel urea breath test for rapid Helicobacter pylori detection and in-office analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:513–20. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200205000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pasricha SR, McQuilten Z, Westerman M, Keller A, Nemeth E, Ganz T, et al. Serum hepcidin as a diagnostic test of iron deficiency in premenopausal female blood donors. Haematologica. 2011;96:1099–105. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2010.037960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akcam M, Ozdem S, Yilmaz A, Gultekin M, Artan R. Serum ferritin, vitamin B(12), folate, and zinc levels in children infected with Helicobacter pylori. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52:405–10. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9422-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gisbert JP, Pajares JM. Review article: 13C-urea breath test in the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection – A critical review. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:1001–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kate V, Kalayarasan R, Ananthakrishnan N. Sequential therapy versus standard triple-drug therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: A Systematic Review of Recent Evidence. Drugs. 2013;73:815–24. doi: 10.1007/s40265-013-0053-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Albrecht P, Kotowska M, Szajewska H. Sequential therapy compared with standard triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication in children: A double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. J Pediatr. 2011;159:45–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vaira D, Zullo A, Vakil N, Gatta L, Ricci C, Perna F, et al. Sequential therapy versus standard triple-drug therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: A randomized trial. Gut. 2007;56:1353–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-8-200704170-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Araf LN, Pereira CA, Machado RS, Raguza D, Kawakami E. Helicobacter pylori and iron-deficiency anemia in adolescents in Brazil. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51:477–80. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181d40cd7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zamani A, Shariat M, Yazdi ZO, Bahremand S, Asbagh PA, Dejakam A. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and serum ferritin level in primary school children of Tehran-Iran. J Pak Med Assoc. 2011;61:658–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seo JK, Ko JS, Choi KD. Serum ferritin and Helicobacter pylori infection in children: A sero-epidemiologic study in Korea. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;17:754–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2002.02797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cardenas VM, Prieto-Jimenez CA, Mulla ZD, Rivera JO, Dominguez DC, Graham DY, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication and change in markers of iron stores among non-iron-deficient children in El Paso, Texas: An etiologic intervention study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011;52:326–32. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182054123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miernyk K, Bruden D, Zanis C, McMahon B, Sacco F, Hennessy T, et al. The effect of Helicobacter pylori infection on iron stores and iron deficiency in urban Alaska Native adults. Helicobacter. 2013;18:222–8. doi: 10.1111/hel.12036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamide A, Sethuraman KR. Helicobacter pylori infection and iron deficiency in school going children of Pondicherry: a seroepidemiologic study project sponsored by DSTE-Pondicherry. 2005. [Accessed June 1, 2013]. Available from: http://www.pon.nic.in/citizen/science/dsteproject/abdul1.pdf .