Abstract

Expression of bile salt export pump (BSEP) is regulated by the bile acid/farnesoid X receptor (FXR) signaling pathway. Two FXR isoforms, FXRα1 and FXRα2, are predominantly expressed in human liver. We previously showed that human BSEP was isoform-dependently regulated by FXR and diminished with altered expression of FXRα1 and FXRα2 in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. In this study, we demonstrate that FXRα1 and FXRα2 regulate human BSEP through two distinct FXR responsive elements (FXRE): IR1a and IR1b. As the predominant regulator, FXRα2 potently transactivated human BSEP through IR1a, while FXRα1 weakly transactivated human BSEP through a newly identified IR1b. Relative expression of FXRα1 and FXRα2 affected human BSEP expression in vitro and in vivo. Electrophoretic mobility shift and chromatin immunoprecipitation assays confirmed the binding and recruitment of FXRα1 and FXRα2 to IR1b and IR1a. Sequence analysis concluded that IR1b was completely conserved among species, whereas IR1a exhibited apparent differences across species. Sequence variations in IR1a were responsible for the observed species difference in BSEP transactivation by FXRα1 and FXRα2. In conclusion, FXR regulates BSEP in an isoform-dependent and species-specific manner through two distinct FXREs, and alteration of relative FXR isoform expression may be a potential mechanism for FXR to precisely regulate human BSEP in response to various physiological and pathological conditions.

Keywords: bile acid transporter, canalicular secretion, gene transcription

Bile acid homeostasis is achieved through an enterohepatic circulation. Canalicular secretion of bile acids through bile salt export pump (BSEP, ABCB11) is the rate-limiting step in the circulation (1, 2). Modulation of BSEP expression or function by inherited or acquired factors has profound impact on biliary and intrahepatic bile acid levels. Indeed, impairment of BSEP function or expression has been directly linked to such diseases as progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis type 2 (3–6), benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis (7–9), intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (10, 11), drug-induced cholestasis (12), and liver cancer (6, 13, 14).

BSEP expression is coordinately regulated by distinct but related transactivation pathways (15–19), notably the bile acids/farnesoid X receptor (FXR, NR1H4) signaling pathway (15, 16). Activation of FXR by bile acids strongly induces BSEP expression in vitro and in vivo (15, 16). Such feed-forward regulation of BSEP by bile acid/FXR is considered a major mechanism for preventing excessive accumulation of toxic bile acids in hepatocytes. Two FXR genes, FXRα and FXRβ, have been identified (20–22). FXRα is functional in all the species tested, while FXRβ is a pseudogene in humans (22). Four isoforms of FXRα (FXRα1–4) have been identified as a result of alternative promoter and splicing (23, 24). Isoforms FXRα1 and FXRα2 are predominantly expressed in the liver and adrenal glands, whereas isoforms FXRα3 and FXRα4 are primarily expressed in the kidneys and intestines in humans (23).

We have recently showed that human BSEP expression was severely diminished in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and that such decreased expression of BSEP correlated with altered relative expression of FXRα1 and FXRα2 (25). Similar to human BSEP, FXRα2 showed more potent activity than FXRα1 in transactivating other hepatic FXR targets, including human syndecan-1 and fibrinogens (26, 27), whereas mouse bsep and small heterodimeric partner (SHP) were regulated by FXRα1 and FXRα2 to similar degrees (24). Currently, the underlying mechanisms for such isoform-dependent and species-specific regulation of BSEP by FXR are not understood.

In this study, we demonstrate that FXRα1 and FXRα2 transactivated human BSEP through two distinct FXR responsive elements (FXRE) that are inverted repeats spaced by one nucleotide (IR1): IR1b and IR1a, respectively. In addition to total FXR expression levels, relative expression of FXRα1 and FXRα2 affected human BSEP expression in vitro and in vivo. Further study revealed that sequence variations in IR1a were responsible for the observed species difference in transactivation of BSEP by FXRα1 and FXRα2.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents and suppliers

Chemicals and reagents for cloning, site-directed mutagenesis, polymerase-chain reaction (PCR), gel-shift assays, cell cultures, transfection, and luciferase assays were described previously (28).

Plasmid constructs

Human, mouse, and rat bsep promoter reporters and mutants, including phBSEP (-2.6kb), pmBSEP(-2.6kb), prBSEP(-2kb), phBSEP(-125b), and phBSEP(-2.6kb)-IR1a-Mut, were prepared previously (18, 28, 29). Human pTK-3xhIR1a, mouse/rat pTK-3xm/rIR1a, and pTK-3xIR1b reporters were constructed by cloning three copies of the corresponding element into pTK-Luc vector. Element reporters pGL3/p-2xhIR1a and pGL3/p-2xhER2/IR1a were prepared by cloning two copies of IR1a and ER2/IR1a element in human BSEP promoter into the pGL3/p vector, respectively. Element reporters, including pElement 1–6, were generated by cloning the corresponding element into the pGL3/p vector. Expression plasmids for human nuclear receptors FXRα2 and FXRα1 were kindly provided by Dr. Matthew Stoner and Dr. David Mangelsdorf (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center), respectively.

Liver samples

Snap-frozen healthy human liver samples were obtained through the Mid-Atlantic Division of the Cooperative Human Tissue Network (CHTN) (University of Virginia). The protocol for using human tissues was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the University of Rhode Island.

Site-directed mutagenesis

Mutations were introduced into the templates using a QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit according to the manufacturer's manual (Stratagene) (29). Human BSEP promoter mutants phBSEP(-2.6kb)-IR1b-Mut, phBSEP(-2.6kb)-IR1ab-Mut, and phBSEP(-2.6kb)-ER2-Mut were prepared by mutating the IR1b, IR1a and IR1b, and half ER2 (everted repeat separated by two nucleotides) sites using phBSEP(-2.6kb) as a template. Six, four, and two nucleotides were mutated in IR1a (GACGCGTGAATTC), IR1b (ATGCCCCTTTACT), and the half ER2 site (AACCCT), respectively (mutated nucleotides are underlined). Rat bsep promoter mutants prBSEP(-2kb)-IR1a-Mut, prBSEP(-2kb)-IR1b-Mut, prBSEP(-2kb)-IR1ab-Mut, and prBSEP(-2kb)-ER2-Mut were prepared by mutating the IR1a, IR1b, IR1a and IR1b, and the half ER2 site using prBSEP(-2kb) as templates. Three, four, and three nucleotides were mutated in IR1a (GGGACATTGATCT), IR1b (ATGCCCCTTTACT), and the half ER2 site (AAAACT), respectively. Replacement of human IR1a (hIR1a) with mouse/rat IR1a (m/rIR1a) was achieved through mutagenesis using phBSEP(-2.6kb) as the template, resulting in a chimeric reporter phBSEP(-2.6kb)-m/rIR1a. Chimeric reporter prBSEP(-2kb)-hIR1a was made through mutagenesis by replacing the mouse/rat IR1a (m/rIR1a) with the human IR1a (hIR1a) using prBSEP(-2kb) as the template. All the mutants were subjected to sequence confirmation.

Immunohistofluorescence

Normal human liver tissue sections embedded in paraffin (ab4348) were obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Deparaffinization, antigen retrieval, and immune staining of the sections were carried out basically according to the protocol recommended by the manufactures. Nonspecific binding was blocked by using 5% BSA in 1× TBS containing 0.1% TX-100 for 2 h on shaker at room temperature. Three types of primary antibodies (Abs) were applied to individual slides, including rabbit anti-FXRα1-specific Abs (custom-made by the NeoBioLab, Woburn, MA), rabbit anti-FXR Abs (sc-13063), and rabbit IgG (sc-2027, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) as negative controls. AlexaFluor 594 goat anti-rabbit Abs (A11012, Invitrogen) was used as the secondary Abs. The sections were then mounted under a glass cover slip using Vectashield mounting medium containing 1.5 μg/ml DAPI (H-1500, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) as nuclei counterstaining. Images were captured under a confocal microscope at a magnification of 40× (Zeiss AxioImager M2 Imaging System) with fluorescent and differential interference contrast (DIC) settings.

Reporter luciferase assay

The reporter luciferase activity assays were carried out using the human hepatoma Huh 7 cells and rat hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) L0 cells (kindly provided by Dr. Jonathan Reicher, Brown University) in a 24-well plate as described previously (28).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays

Nuclear extracts of Huh 7 cells transfected with FXRα1 or FXRα2 were prepared using the NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction kit (Pierce). The electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) were performed using the LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA kit (Pierce) as described (17). Supershift assays were carried out using polyclonal Abs against human FXR (sc-13063, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays

Huh 7 cells seeded in 6-well plates were cotransfected with 400 ng of either FXRα1 or FXRα2 and either 400 ng phBSEP(-2.6kb), phBSEP(-2.6kb)-IR1a-Mut, phBSEP(-2.6kb)-IR1b-Mut, or phBSEP(-2.6kb)-IR1ab-Mut. Sixteen hours posttransfection, cells were treated with 10 μM CDCA for 24 h. Chromatin preparation and immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed essentially as described previously (28). A test set of primers, BSEP(-260b) and pGL4-R(122), flanking IR1a and IR1b were used to amplify a 462 bp fragment encompassing sequence from nucleotides −260 to +80 in the BSEP promoter and 122 nucleotides in the luciferase gene. A negative control set of primers was included in the assays (28).

Living imaging with in vivo imaging system

Sixteen female CD-1 mice between ages 5 and 8 weeks were obtained from Charles River Laboratory (Wilmington, MA) and randomly divided into four groups. Each group of mice was hydrodynamically injected with phBSEP(-2.6kb), prBSEP(-2kb), phBSEP(-2.6kb)-m/rIR1a, or prBSEP(-2kb)-hIR1a promoter reporter as described previously (25). Luciferase activities were detected by living imaging with in vivo imaging system (IVIS) 48 h postinjection and captured by a CCD camera with an exposure time of 45 s (25). The animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Rhode Island (URI) and followed the guidelines outlined in the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA extraction from 14 healthy human and 8 CD-1 mice liver tissues and subsequent cDNA synthesis and TaqMan real-time PCR detection for total FXR and BSEP were carried out as reported (17, 25).

Semiquantification of FXRα1 and FXRα2

By using human liver cDNA samples as templates, the relative FXRα1 and FXRα2 mRNA levels were determined by the semiquantification methods described previously (25).

Statistical analysis

Student t-test was applied to pair-wise comparison to determine the statistical significance. Nonparametric Mann-Whitney test was used for pair-wise comparison for nonnormally distributed data. Values of 0.05 or less were considered significant.

RESULTS

Isoform-dependent and species-specific regulation of BSEP transactivation by FXR

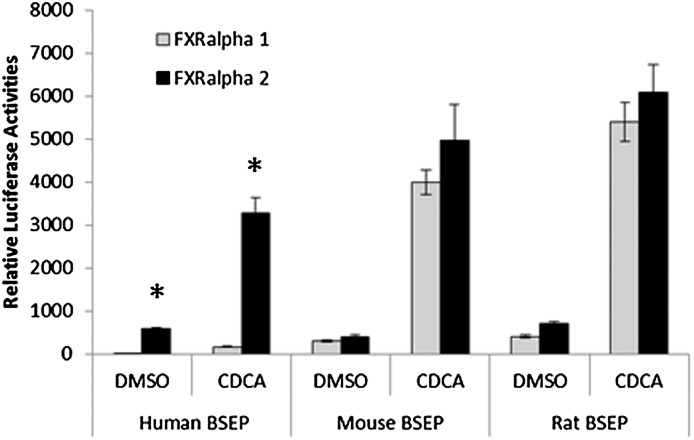

Four FXRα isoforms (FXRα1–4) have been identified, with predominant expression of FXRα1 and FXRα2 in the liver (23, 24). Our previous study showed that human BSEP was regulated by FXR in an isoform-dependent manner and that alteration of isoform expression was associated with dysregulation of BSEP in patients with HCC (25). In this study, we extended such finding by testing FXR isoform-mediated transactivation of BSEP from three species, including human, mouse, and rat. Consistent with our previous findings, FXRα2 exhibited much more potent activity in transactivating human BSEP than FXRα1 in the presence or absence of endogenous FXR agonist chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA) (Fig. 1). In contrast, both mouse and rat bsep were transactivated by FXRα1 and FXRα2 in comparable levels (Fig. 1). The results demonstrated that human BSEP was differentially regulated by FXRα1 and FXRα2 with FXRα2 being the predominant regulator, whereas mouse and rat bsep were similarly transactivated by the two isoforms.

Fig. 1.

Transactivation of BSEP by FXRα1 and FXRα2. Human, mouse, and rat bsep promoter reporters phBSEP(-2.6kb), pmBSEP(-2.6kb), and prBSEP(-2kb) were cotransfected into human hepatoma Huh 7 cells with either FXRα1 or FXRα2 expression plasmid, followed by treatment of the transfected cells with vehicle DMSO (0.1%) or CDCA (10 μM) for 30 h. Reporter transactivation levels as luciferase activities were detected with a dual-luciferase reporter assay system. The firefly luminescence was normalized based on the Renilla luminescence signal. The data are presented as mean ± SD of at least three separate experiments. *P < 0.05 between DMSO and CDCA-treated cells (Student t-test).

Relative FXR isoform and total FXR expression affected the expression levels of human BSEP

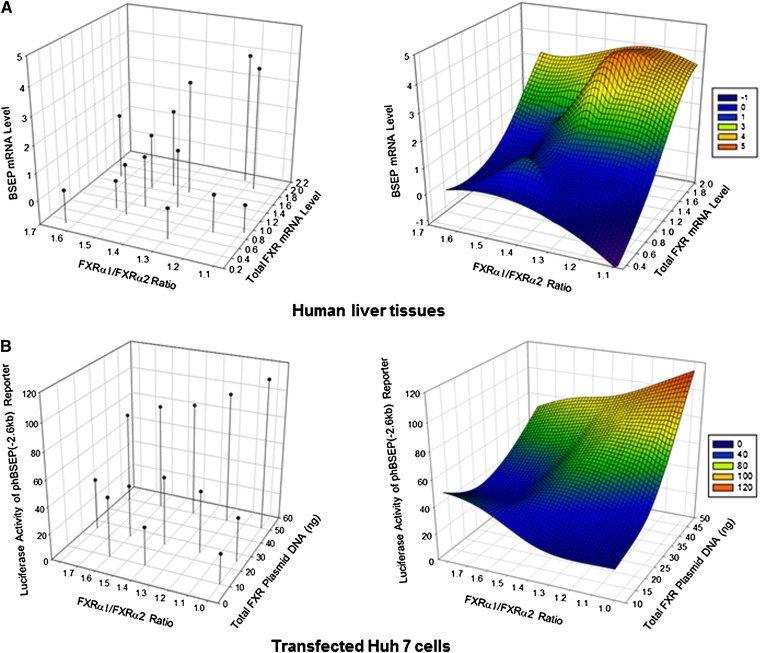

In our previous studies, it was shown that the relative expression levels of FXRα1 and FXRα2 correlated with BSEP expression (25). In this study, the comprehensive relationships among FXR isoforms, total FXR expression, and BSEP expression were further investigated. As shown in Fig. 2A, the expression levels of BSEP and total FXR in healthy human liver samples were plotted against FXRα1/FXRα2 ratios using SigmaPlot 3D program. Over 27- and 6-fold differences in BSEP and total FXR expression, respectively, were detected among the liver samples. Consistent with FXR's transactivating role in BSEP regulation, BSEP expression increased along with increase in total FXR. However, the relationship between FXRα1/FXRα2 ratios and BSEP expression did not exhibit a single trend (Fig. 2A). At higher levels of total FXR, as expected, BSEP expression decreased as the FXRα1/FXRα2 ratios increased. However, at lower levels of total FXR, BSEP expression increased as the FXRα1/FXRα2 ratios increased. The data thus indicated that BSEP expression in human livers was dictated by the FXRα1/FXRα2 ratios as well as by total FXR expression levels.

Fig. 2.

The effects of relative expression levels of FXRα1 and FXRα2 on BSEP expression in human liver tissues and Huh 7 cells. (A) mRNA expression levels of BSEP and total FXR in healthy human liver tissues were determined by TaqMan real-time PCR and plotted against FXRα1/FXRα2 ratios using SigmaPlot version 11.0. The cycle time (Ct) values Ct24.92 for FXR and Ct27.12 for BSEP of one tissue sample were designated as a relative unit 1. (B) A series of mixtures of FXRα1 and FXRα2 plasmid DNA in various FXRα1/FXRα2 ratios (from 1.0, 1.2, 1.4, 1.6 to 1.8) with a constant amount of total FXR at 10, 25, or 50 ng were cotransfected with human BSEP promoter reporter in Huh 7 cells, followed by treatment of the transfected cells with CDCA for 30 h and subsequent detection of luciferase activity. FXRα1/FXRα2 ratios were plotted against total FXR and BSEP promoter transactivation as luciferase activities using SigmaPlot version 11.0. The left figure shows the level and position of each individual sample in the 3D diagram. The right figure is the smooth 3D model based on the data shown on the left.

To directly evaluate the effect of FXRα1/FXRα2 ratios at various total FXR levels on BSEP transactivation in vitro, a series of mixtures of FXRα1 and FXRα2 plasmid DNA in various ratios (from 1:1 to 1.8:1) at various amounts of total FXR (10, 25, or 50 ng) were cotransfected with the human BSEP promoter reporter in Huh 7 cells, followed by treatment with CDCA. As shown in Fig. 2B, a relationship pattern comparable to human liver samples (Fig. 2A) was observed in transfected Huh 7 cells. BSEP transactivation gradually decreased as the FXRα1/FXRα2 ratios increased at a high level of total FXR plasmid DNA (50 ng) but increased at a low level of total FXR plasmid DNA (10 ng). The minor differences between the two data sets (Fig. 2) may reflect the fact that the sample size of human liver samples was relatively small. Taken together, the results demonstrated that the ratio of FXRα1/FXRα2 played an important role in determining human BSEP transactivation and that its effects were influenced by the total FXR expression levels.

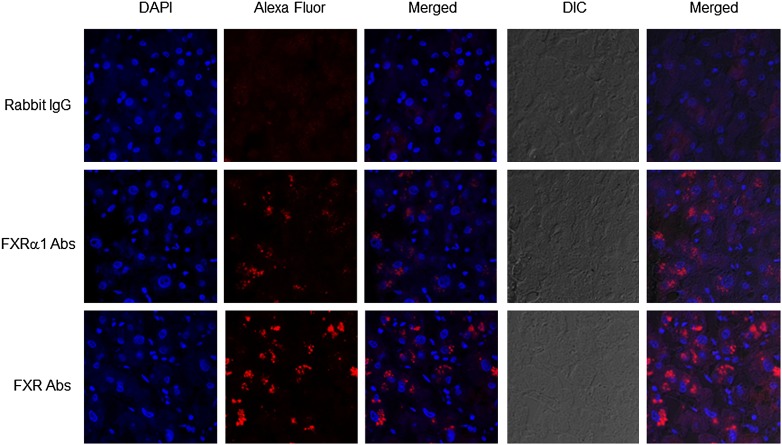

Expression and localization of FXRα1 and total FXR protein in human liver tissue

Immunohistofluorescence was carried out to investigate the expression and localization of total FXR and FXRα1. In our attempt to generate FXR isoform-specific Abs, antiserum raised against FXRα1-specific peptide detected FXRα1 protein specifically, whereas antiserum raised against FXRα2-specific peptide recognized both FXRα2 and FXRα1 protein (data not shown) because there are only four extract amino acids inserted in FXRα1 compared with FXRα2. Therefore, FXRα1-specific Abs and Abs recognizing both FXRα1 and FXRα2 were used in the immunohistofluorescent assays. As shown in Fig. 3, minimal red fluorescent signals were detected with rabbit IgG as negative controls while FXRα1 and total FXR proteins were readily detected with FXRα1- and FXR-specific Abs. Both FXRα1 and total FXR proteins were predominantly present in the cytoplasm. As expected, relatively weaker signals were detected with FXRα1-specific Abs than with FXR-specific Abs.

Fig. 3.

Expression and localization of FXRα1 and total FXR in human liver tissues. Liver sections were subjected to immunohistofluorescent assays. FXRα1- and FXR-specific Abs and rabbit IgG as negative controls were used as primary Abs. Goat anti-rabbit Abs labeled with AlexaFluor 594 was used as the secondary Abs. Mounting medium containing DAPI (1.5 μg/ml) was used as nuclei counterstaining. Images were captured under a confocal microscope at a magnification of 40× with both fluorescent and DIC settings.

Isoform-dependent transactivation of human BSEP by FXR was not due to a difference in ligand-mediated activation

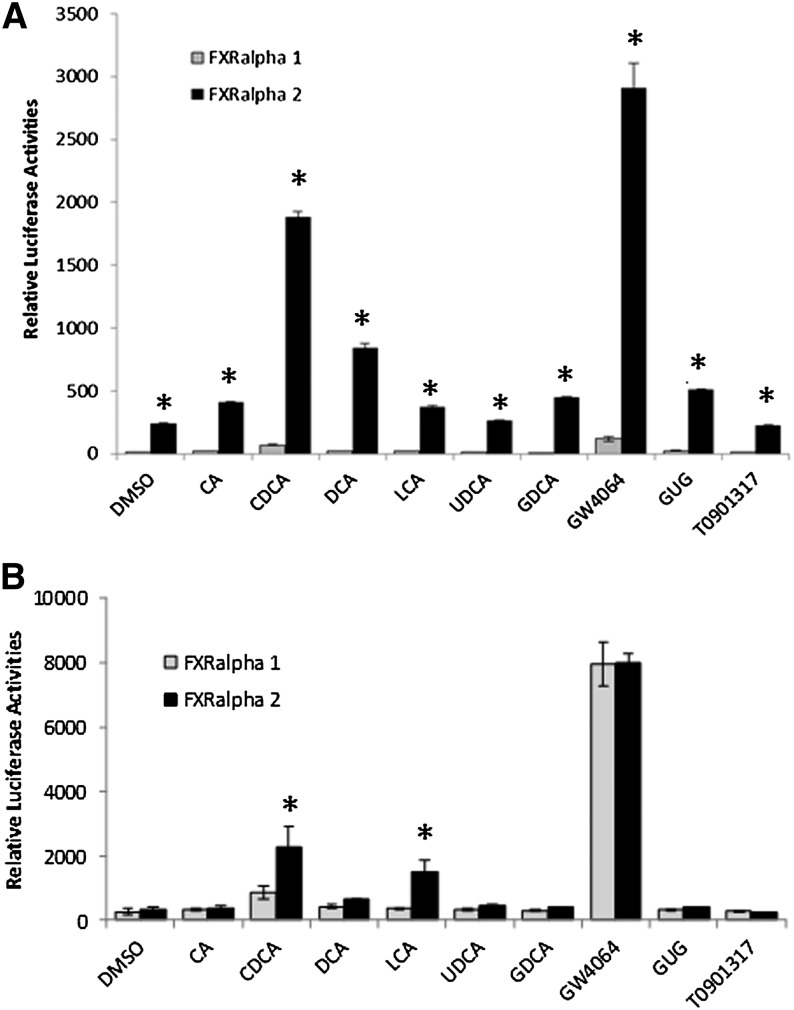

In the previous experiments, the potent endogenous FXR agonist CDCA was used in evaluating human BSEP transactivation by FXR isoforms. To determine whether FXRα1- and FXRα2 -mediated differential transactivation of human BSEP is related to specific FXR ligands, a series of FXR endogenous and exogenous ligands were tested for their ability to induce FXRα1- and FXRα2-mediated transactivation of human BSEP. The ligands tested include six endogenous bile acids, including cholic acid (CA), CDCA, deoxycholic acid (DCA), lithocholic acid (LCA), ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) and glycodeoxycholic acid (GDCA), a natural product guggulsterone, and two synthetic FXR agonists GW4064 and T0901317. As shown in Fig. 4A, all the FXR ligands exhibited similar FXR isoform-dependent transactivation of human BSEP regardless their agonistic potency. FXRα2 consistently transactivated human BSEP at a much higher level than FXRα1 with each of the ligands.

Fig. 4.

Transactivation of BSEP promoters by FXRα1 and FXRα2 with various FXR ligands. (A) Human BSEP promoter reporter phBSEP(-2.6kb) and (B) rat bsep promoter reporter prBSEP(-2kb) were cotransfected into human hepatoma Huh 7 cells and rat HCC L0 cells, respectively, with FXRα1 or FXRα2, followed by treatment of transfected cells with various endogenous and exogenous FXR ligands, including CA (10 μM), CDCA (10 μM), DCA (10 μM), LCA (10 μM), UDCA (10 μM), GDCA (10 μM), GW4064 (1 μM), GUG (10 μM), and T0901317 (1 μM). Thirty hours post treatment, reporter transactivation levels as luciferase activities were detected with a dual-luciferase reporter assay system. The firefly luminescence was normalized based on the Renilla luminescence signal. The data are presented as mean ± SD of at least three separate experiments. *P < 0.05 between FXRα1 and FXRα2-transfected cells (Student t-test).

In contrast to human BSEP, both mouse and rat bsep promoters exhibited comparable transactivation activities by FXRα1 and FXRα2, with slightly higher levels with FXRα2 in the presence of CDCA in Huh 7 cells (Fig. 1). Considering the possibility that rat or mouse bsep may exhibit a different transactivation pattern by FXRα1 and FXRα2 in rat or mouse cells, rat bsep promoter reporter prBSEP(-2kb) was cotransfected with FXRα1 or FXRα2 in rat HCC L0 cells, followed by treatment with various FXR ligands. As shown in Fig. 4B, consistent with the data from Huh 7 cells, FXRα1 and FXRα2 exhibited similar transactivation levels with most FXR ligands, except for CDCA and LCA. FXRα2 transactivated rat bsep more potently than did FXRα1 with CDCA and LCA. However, it should be emphasized that the differences between FXRα2 and FXRα1 in transactivating human BSEP in Huh 7 cells were much more striking than those with rat bsep in rat HCC L0 cells. FXRα2 was 27.1- or 18.9-fold more potent than FXRα1 in transacting human BSEP in Huh 7 cells in the presence of CDCA or LCA, whereas only 2.6- or 4.1-fold differences were observed between FXRα2 and FXRα1 in transactivating rat bsep in L0 cells with CDCA or LCA.

Taken together, the data indicated that the isoform-dependent transactivation of human BSEP by FXR was not due to a difference between FXRα1 and FXRα2 in ligand binding or ligand-mediated activation. On the other hand, FXRα1 and FXRα2 transactivated rat bsep comparably with most of the FXR ligands.

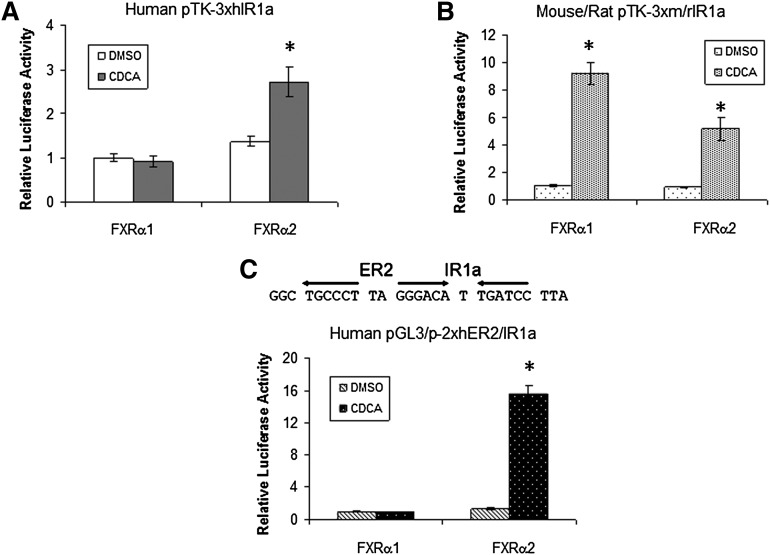

Isoform-dependent and species-specific transactivation of BSEP by FXR was due to a difference in FXRE in BSEP promoters

Early studies identified an FXRE (named IR1a) in the BSEP promoter (15, 16). To determine whether the isoform-dependent and species-specific transactivation of BSEP is due to a differential activation of the IR1a by FXRα1 and FXRα2, human and mouse/rat IR1a (hIR1a and m/rIR1a) reporters were constructed and tested for their ability to support FXRα1 or FXRα2 transactivation. It should be mentioned that the IR1a sequences are completely conserved in mouse and rat bsep promoters. As shown in Fig. 5A, FXRα2 significantly transactivated hIR1a reporter, whereas no transactivation was detected in cells transfected with FXRα1. Conversely, both FXRα1 and FXRα2 strongly transactivated m/rIR1a reporter (Fig. 5B). The results thus demonstrated that hIR1a only supported FXRα2 transactivation, while m/rIR1a was capable of mediating both FXRα1 and FXRα2 transactivation.

Fig. 5.

Isoform-dependent and species-specific transactivation of IR1a reporters by FXRα1 and FXRα2. (A) Human BSEP IR1a reporter pTK-3xhIR1a, (B) mouse/rat bsep IR1a reporter pTK-3xm/rIR1a, and (C) human BSEP ER2/IR1a reporter pGL3/p-2xhER2/IR1a were cotransfected with FXRα1 or FXRα2, followed by treatment of the cells with DMSO (0.1%) or CDCA (10 μM) for 30 h. Reporter luciferase activities were detected with the dual-luciferase reporter assay system. The data are presented as mean ± SD of at least three repeated experiments. *P < 0.05 between DMSO and CDCA-treated cells (Student t-test).

Previous studies revealed that half nuclear receptor binding site and ER2 (everted repeat separated by two nucleotides) are commonly found adjacent to the IR1 (30). A half ER2 motif was identified immediately upstream the IR1a (Fig. 5C). Inclusion of the motif in hER2/IR1a reporter significantly enhanced FXRα2-mediated transactivation (Fig. 5C), indicating that the half ER2 motif is required for maximal transactivation of human BSEP by FXRα2. However, FXRα1 still failed to transactivate the hER2/IR1a reporter, suggesting that FXRα1 must regulate human BSEP through an additional FXRE.

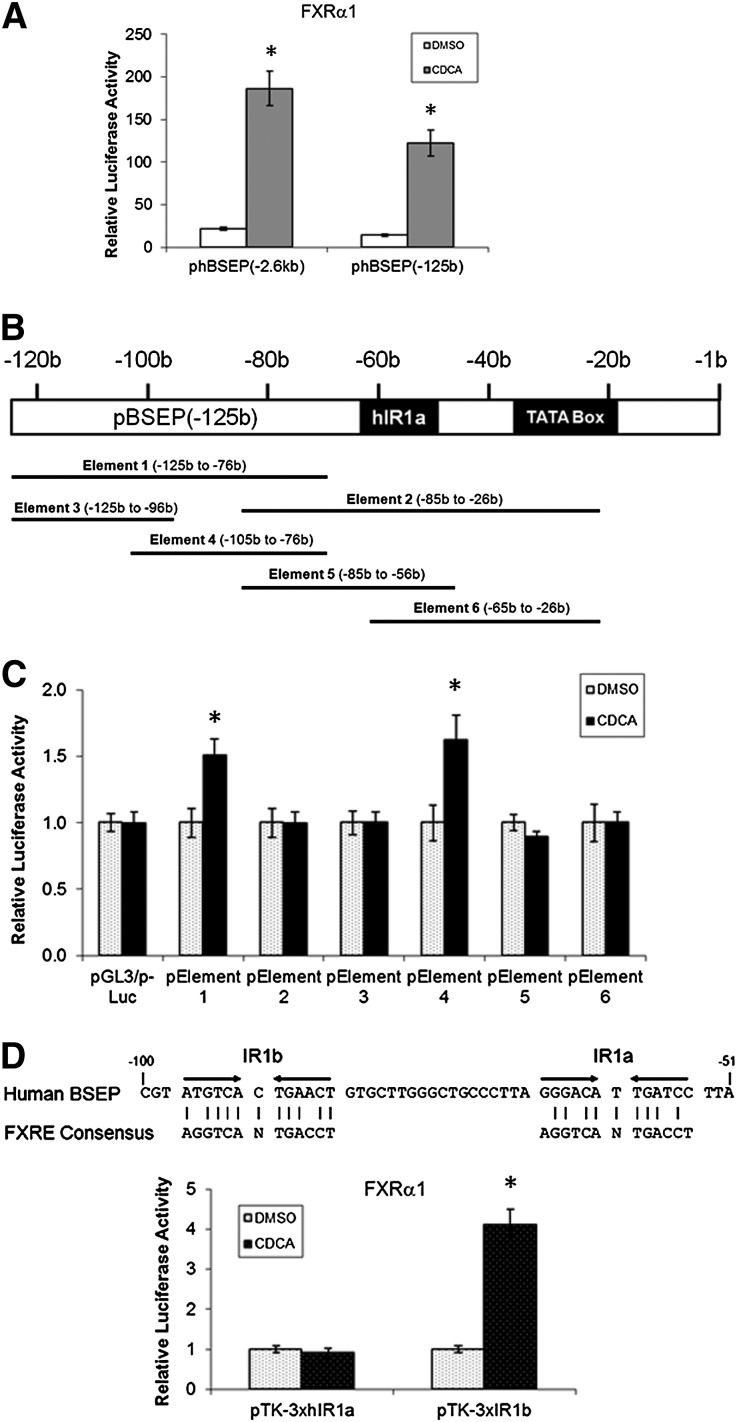

FXRα1 transactivated human BSEP through IR1b, a newly identified FXRE

To determine whether the potential additional FXRE is present in the minimal human BSEP promoter, the resultant phBSEP(-125b) reporter was cotransfected with FXRα1, followed by treatment with DMSO or CDCA. As shown in Fig. 6A, similar to the full-length promoter reporter phBSEP(-2.6kb), FXRα1 significantly transactivated the minimal promoter reporter, indicating that the potential additional FXRE is located in the minimal promoter region.

Fig. 6.

FXRα1 transactivated human BSEP through a newly identified FXRE, IR1b. (A) Full-length and minimal human BSEP promoter reporters phBSEP(-2.6kb) and phBSEP(-125b) were cotransfected with FXRα1 in Huh 7 cells. Sixteen hours posttransfection, cells were treated with DMSO (0.1%) and CDCA (10 μM) for 30 h, followed by detection luciferase activities with dual-luciferase reporter assay system. The data are presented as mean ± SD of at least three repeated experiments. (B) A diagram showing the positions of the six elements in the minimal promoter region. (C) The six elements were cloned into the pGL3/p-Luc vector, resulting in six element reporters, pElement 1 to 6. Activation of the six element reporters by FXRα1 in the presence of CDCA (10 μM) was detected by the dual-luciferase reporter assay system. The data are presented as mean ± SD of at least three repeated experiments. *P < 0.05 between DMSO and CDCA-treated cells (Student t-test). (D) The location and sequence of the newly identified IR1b are shown in the upper panel. Transactivation of hIR1a and IR1b reporters by FXRα1 are presented in the lower panel. Reporters pTK-3xhIR1a and pTK-3xIR1b were cotransfected into Huh 7 cells with FXRα1, followed by treating the cells with DMSO (0.1%) or CDCA (10 μM) for 30 h prior to detection of luciferase activities as described in (A). *P < 0.05 between DMSO and CDCA-treated cells (Student t-test).

Since no FXREs were predicted by bioinformatic analysis in the region, a series of element reporters covering the entire region were constructed and evaluated for their ability to respond to FXRα1 (Fig. 6B, C). Reporters pElement 1 and 4 exhibited significant induction of activity in response to CDCA in the presence of FXRα1, whereas no induction was detected with other reporters. The data thus mapped a new functional FXRE (named IR1b) in the overlapped region between pElement 1 and 4 at positions from −97b to −85b (Fig. 6D). The IR1b was physically close to IR1a (18 bases from each other). To confirm that the newly identified IR1b is functional in supporting FXRα1 transactivation, IR1b reporter pTK-3xIR1b was constructed and tested. As shown in Fig. 6D, FXRα1 moderately transactivated IR1b reporter in the presence of CDCA, confirming that FXRα1 regulates human BSEP through IR1b.

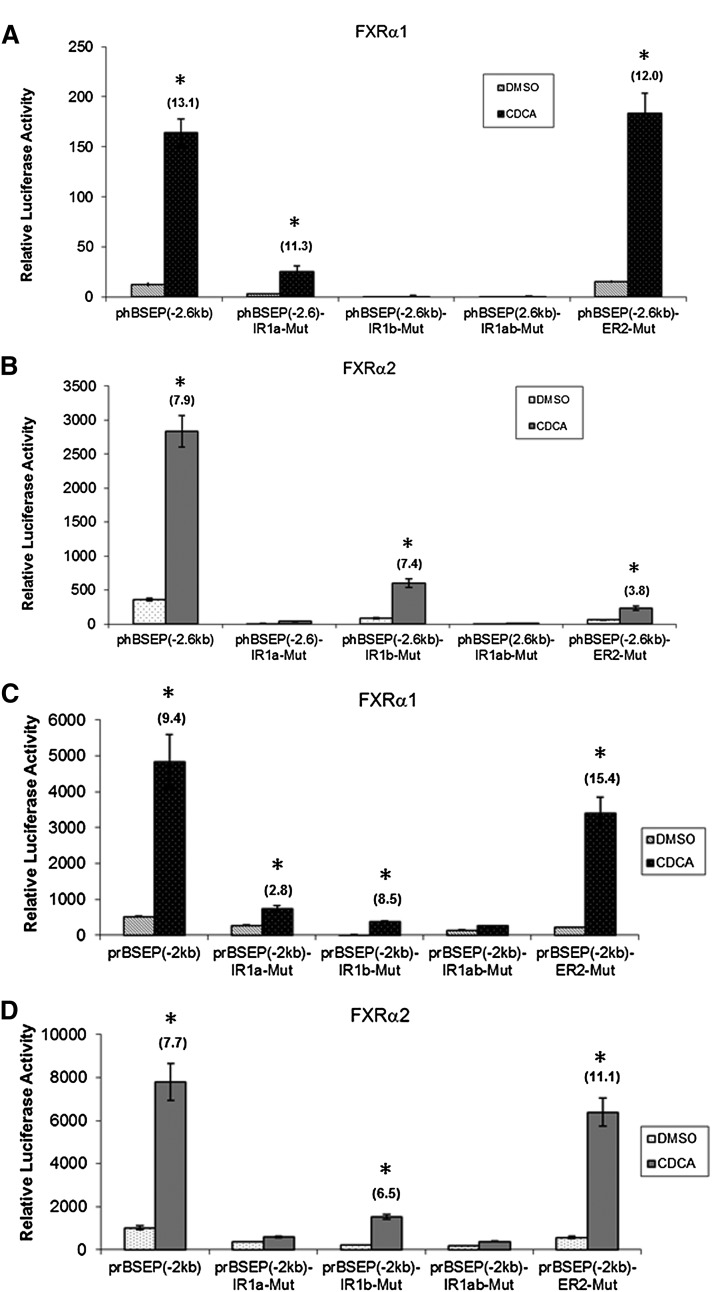

Mutational analysis of IR1a and IR1b in supporting FXRα1- and FXRα2-mediated transactivation of human and rat bsep

To determine the relative contribution of IR1a, IR1b, and the half ER2 sites to the transactivation of human and rat bsep by FXRα1 and FXRα2, mutational analyses were performed in those elements. Double mutation in IR1a and IR1b was also introduced.

For human BSEP, similar to the IR1a and IR1b double mutant, IR1b mutant completely lost its ability to respond to FXRα1 (Fig. 7A), suggesting that FXRα1 regulates human BSEP through IR1b. Although mutation in IR1a decreased FXRα1-mediated transactivation, significant induction remained (Fig. 7A). More significantly, the fold induction by CDCA over DMSO was comparable between IR1a mutant and wild-type (wt) (13.1 versus 11.3), indicating that IR1a is required for basal activity but not FXRα1-mediated transactivation. Conversely, mutation in IR1a almost entirely abolished FXRα2-mediated transactivation as did the double mutant (Fig. 7B), consistent with regulation of human BSEP by FXRα2 through IR1a. Similarly, the IR1b mutant retained the ability to respond to CDCA in the presence of FXRα2 with almost identical fold inductions as the wt (7.9 versus 7.4) (Fig. 7B). Mutation in the half ER2 motif markedly reduced FXRα2- but not FXRα1-mediated transactivation (Fig. 7A, B). Taken together, the data demonstrated that FXRα1 and FXRα2 transactivated human BSEP through IR1b and IR1a, respectively, and that the ER2 motif is required for maximal FXRα2 transactivation.

Fig. 7.

Mutational analysis of IR1a and IR1b in BSEP promoters. Four human BSEP promoter mutants with mutation in IR1a, IR1b, the half ER2 site, or both IR1a and IR1b were made using human BSEP promoter reporter phBSEP(-2.6kb) as parental template, resulting in mutants phBSEP(-2.6kb)-IR1a-Mut, phBSEP(-2.6kb)-IR1b-Mut, phBSEP(-2.6kb)-IR1ab-Mut, and phBSEP(-2.6kb)-ER2-Mut. Four equivalent mutants were constructed using rat bsep promoter reporter prBSEP(-2kb) as parental template, resulting in prBSEP(-2kb)-IR1a-Mut, prBSEP(-2kb)-IR1b-Mut, prBSEP(-2kb)-IR1ab-Mut, and prBSEP(-2kb)-ER2-Mut. The four human BSEP promoter mutants and wt were cotransfected with (A) FXRα1 or (B) FXRα2 into Huh 7 cells. The four rat bsep promoter mutants and wt were cotransfected with (C) FXRα1 or (D) FXRα2. Sixteen hours posttransfection, cells were treated with DMSO (0.1%) or CDCA (10 μM) for 30 h, followed by detection of luciferase activities by the dual-luciferase reporter assay system. The data are presented as mean ± SD of at least three repeated experiments. *P < 0.05 between DMSO and CDCA-treated cells (Student t-test). The fold inductions by CDCA over DMSO are presented on the top of the bars.

Similar mutational analyses were performed with rat bsep promoter to evaluate species differences. As shown in Fig. 7C, mutation in IR1a or IR1b resulted in a decrease in FXRα1-mediated transactivation. However, significant activation by CDCA remained for both mutants. As expected, the double mutant almost completely lost its ability to respond to CDCA. The results indicated that different from human BSEP, FXRα1 regulated rat bsep through both IR1a and IR1b. Conversely, mutation in IR1a almost totally abolished FXRα2-mediated transactivation as did the double mutant, indicating that FXRα2 regulates rat bsep through IR1a. Although mutation in IR1b decreased FXRα2-mediated transactivation, significant induction by CDCA was detected with a comparable fold induction to the wt (7.7 versus 6.5) (Fig. 7D), indicating that similar to human BSEP, IR1b is required for basal activity but not for FXRα2-mediated transactivation. Mutation in the half ER2 site had no detectable effect on FXRα1- and FXRα2-mediated transactivation (Fig. 7C, D), suggesting that different from human BSEP, the half ER2 in rat bsep does not play any roles in mediating FXRα2 transactivation.

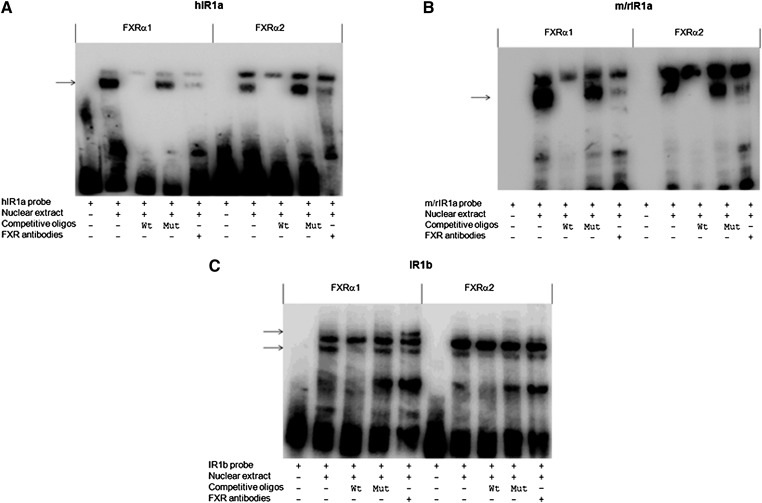

Binding of FXRα1 and FXRα2 to IR1a and IR1b in vitro

To determine whether FXR isoforms differentially bind to IR1a and IR1b in vitro, a series of EMSA assays were performed. With hIR1a and m/rIR1a probes, two distinct bands were shifted for both FXRα1 and FXRα2, indicating that two DNA/protein complexes were formed (Fig. 8A, B). To determine which band represents the specific binding of FXRα1 or FXRα2 to the probe, competition assays were carried out. The dominant bottom band was completely competed out by 10× unlabeled wt but not by mutated hIR1a or m/rIR1a oligonucleotide, indicating that the bottom band represented the probe-specific complex. To confirm that FXRα1 or FXRα2 is part of the complex, supershift assays with Abs against FXR were performed. Preincubation of FXR Abs with nuclear extracts markedly decreased the shifted band, suggesting that the binding of FXR Abs to FXR interferes with its binding to the hIR1a or m/rIR1a probe, decreasing the formation of the DNA/FXR complexes. The data thus demonstrated that both FXRα1 and FXRα2 bound to hIR1a or m/rIR1a abundantly in vitro. The abundant binding of FXRα1 to hIR1a was not expected since FXRα1 failed to transactivate hIR1a reporter.

Fig. 8.

Binding of FXRα1 and FXRα2 to IR1a and IR1b in vitro. EMSAs were performed using (A) human hIR1a, (B) mouse/rat m/rIR1a, or (C) IR1b as probe. Nuclear extracts were prepared from Huh 7 cells transfected with FXRα1 or FXRα2. The specificity of the binding was established with competition assays using competing oligonucleotides, including unlabeled or mutated probe with 10× concentration. Identification of FXR protein in the shifted complex was carried out by supershift assays using polyclonal Abs against human FXR. The shifted bands representing the specific binding of FXR to the probe or FXR Abs to FXR/DNA complex are indicated by arrows.

With IR1b as a probe, two similar bands were shifted with FXRα1 and FXRα2. Competition EMSA assays concluded that the bottom band was the specific one. Incubation of FXR Abs with the complex resulted in a supershifted band (Fig. 8C), indicating that FXR is part of the complex. It should be emphasized that although similarly shifted patterns were observed for both FXRα1 and FXRα2, the bands shifted or supershifted with FXRα1 were much more abundant than those with FXRα2, suggesting that FXRα1 has a higher binding affinity to IR1b than does FXRα2.

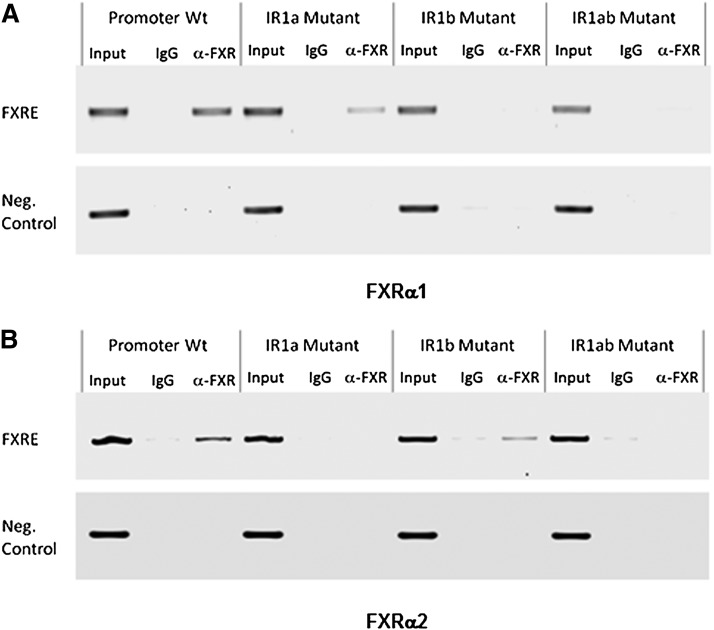

FXRα1 and FXRα2 were specifically recruited to IR1b and IR1a, respectively, in human BSEP promoter in intact cells

Since IR1a and IR1b are located so close to each other, it was challenging to distinguish FXR recruitment to each individual site on the endogenous BSEP promoter. We used human BSEP promoter reporter wt and mutants to perform ChIP assays. Chromatins were prepared from Huh 7 cells cotransfected with FXRα1 or FXRα2 with human BSEP promoter wt, IR1a, IR1b, or IR1ab mutant. With FXRα1, a PCR band was readily detected in cells transfected with wt promoter when the chromatins were immunoprecipitated with anti-FXR Abs but not with IgG (Fig. 9A). More importantly, a PCR band with a relatively weaker signal was also detected in cells transfected with IR1a mutant. In contrast, no obvious bands were detected in cells transfected with either IR1b mutant or IR1ab double mutant (Fig. 9A). The data thus established that FXRα1 was specifically recruited to IR1b but not IR1a in intact Huh 7 cells. On the other hand, with FXRα2, a PCR band was readily detected in cells transfected with wt and IR1b mutant, whereas no signals were detected in cells transfected with IR1a and IR1ab double mutant (Fig. 9B). The data thus demonstrated that FXRα2 was specifically recruited to IR1a but not IR1b.

Fig. 9.

Recruitment of FXRα1 and FXRα2 to IR1a and IR1b in intact cells. ChIP assays were carried out using chromatins prepared from Huh 7 cells cotransfected with (A) FXRα1 or (B) FXRα2 with human BSEP promoter reporter wt, IR1a, IR1b, or IR1ab double mutant. After immunoprecipitated with anti-FXR Abs or IgG as negative control, recruitment of FXRα1 or FXRα2 to IR1a or IR1b was detected by PCR using a set of primers, BSEP(-260b) and pGL-R(122), flanking the two IR1 sites in the reporter plasmid DNA. A negative control primer set, BSEP(-995b) and BSEP(-805b), was used to amplify a fragment approximately 700b upstream the IR1 sites. Input chromatin DNA was included as a positive PCR control.

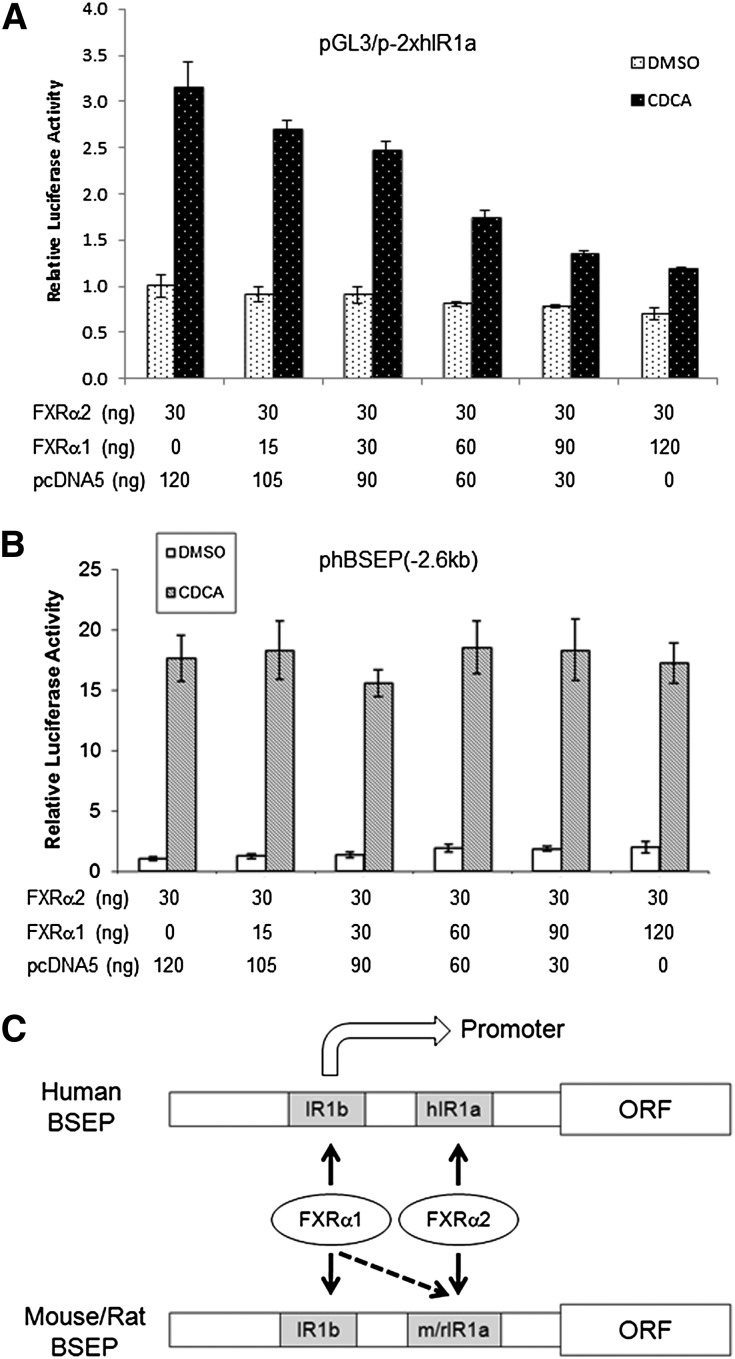

FXRα1 and FXRα2 acted independently in transactivating human BSEP

To investigate whether FXRα1 and FXRα2 have additive or competitive effects on the transactivation of human BSEP IR1a element reporter and full-length promoter, increasing amounts of FXRα1 were cotransfected with a constant amount of FXRα2, followed by detection of the transactivation levels. As shown in Fig. 10A, FXRα1 competitively decreased FXRα2-mediated transactivation in cells transfected with IR1a element reporter pGL3/p-2xhIR1a. In contrast, FXRα1 had minimal effects on FXRα2-mediated transactivation of the full-length promoter reporter phBSEP(-2.6kb), even at the highest dose (Fig. 10B). The results indicated that FXRα1 competitively bound to IR1a with FXRα2 in the IR1a element reporter, which is consistent with the data from EMSA (Fig. 8A). The results also indicated that no competitive binding of FXRα1 to IR1a occurred in the full-length promoter, which is consistent with the data from the ChIP assays (Fig. 9A). Such discrepancy in FXRα1’s effects on FXRα2-mediated transactivation of IR1a element and full-length promoter indicated that the context of IR1a played a determinant role in responding to FXRα1. It was thus concluded that in the content of full-length promoter, FXRα1 and FXRα2 transactivated human BSEP independently through IR1b and IR1a, respectively and that BSEP expression levels were predominately determined by FXRα2.

Fig. 10.

Interrelationship between FXRα1 and FXRα2. The effects of FXRα1 on FXRα2-mediated transactivation of (A) human IR1a element reporter pGL3/p-2xhIR1a and (B) full-length human BSEP promoter reporter phBSEP(-2.6kb) were investigated. Increasing amounts of FXRα1 were cotransfected with a constant amount of FXRα2 and pGL3/p-2xhIR1a or phBSEP(-2.6kb). Vector pcDNA5 plasmid DNAs were also cotransfected to obtain a constant total plasmid DNA in each well. Sixteen hours posttransfection, cells were treated with DMSO (0.1%) or CDCA (10 μM) for 30 h, followed by detection of luciferase activity. The data are presented as mean ± SD of at least three repeated experiments. (C) A diagram summarizing FXRα1- and FXRα2-mediated transactivation of BSEP through IR1a and IR1b. In human, FXRα1 and FXRα2 regulate BSEP exclusively through IR1b and hIR1a, respectively. In mouse and rat, FXRα1 is able to transactivate BSEP through both m/rIR1a and IR1b, whereas FXRα2 transactivates exclusively through m/rIR1a.

Combining the data from transactivation, mutational analysis, EMSA and ChIP assays, it was concluded that FXRα1 and FXRα2 regulated human BSEP independently through IR1b and IR1a. On the other hand, mouse and rat bsep are regulated by FXRα1 through both IR1a and IR1b and by FXRα2 through IR1a (Fig. 10C).

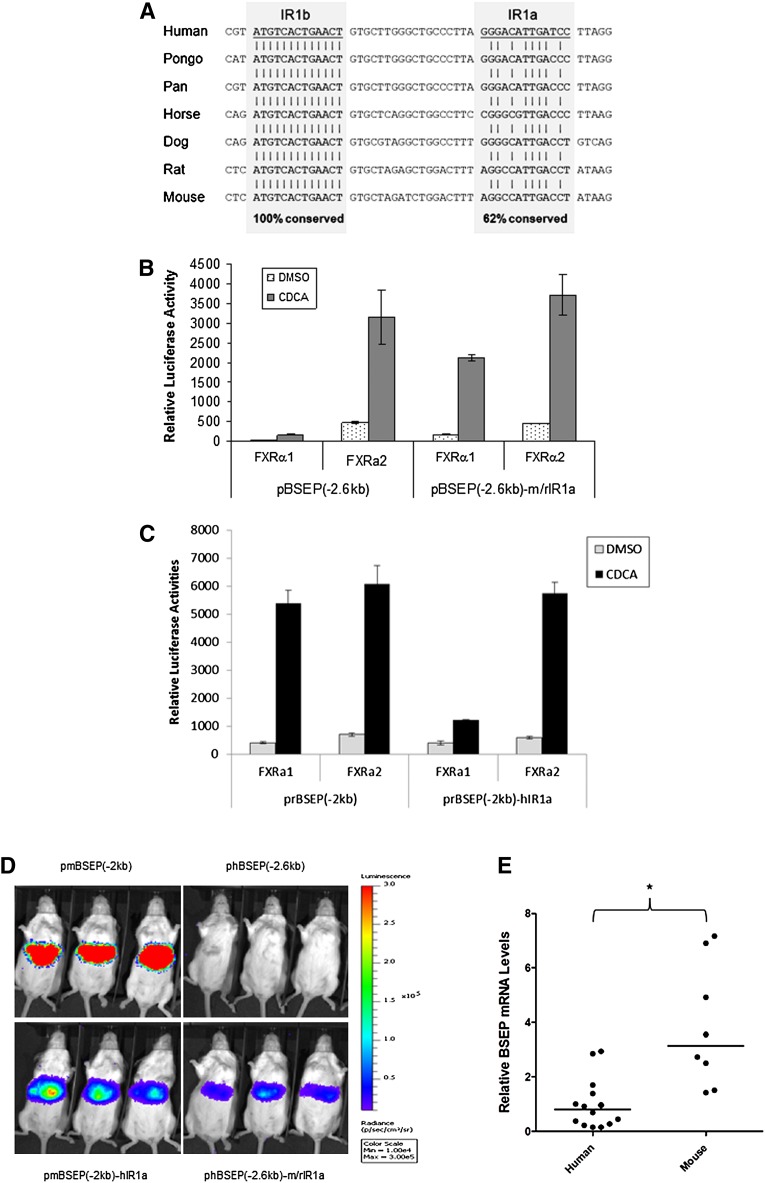

Sequence differences between hIR1a and m/rIR1a were primarily responsible for the species-specific transactivation of BSEP by FXRα1 and FXRα2

Sequence alignment of IR1a and IR1b in BSEP promoters from seven species including human, pongo pygmaeus, pan troglodytes, horse, dog, rat, and mouse revealed that IR1b was completely conserved (Fig. 11A), indicating the importance of the element in regulating BSEP expression. On the other hand, IR1a was less conserved with 62% sequence identity among those species.

Fig. 11.

IR1b is completely conserved among species, whereas IR1a is primarily responsible for the species difference in transactivation of BSEP by FXRα1 and FXRα2. (A) Sequences of the IR1a and IR1b from seven species including mouse, rat, dog, cat, horse, primate, and human were aligned. The overall conservation percentages of IR1a and IR1b are indicated. (B) The hIR1a in human BSEP promoter reporter phBSEP(-2.6kb) was replaced with mouse/rat m/rIR1a, generating a chimeric reporter pBSEP(-2.6kb)-m/rIR1a. (C) The rIR1a in rat bsep promoter reporter prBSEP(-2kb) was replaced with human hIR1a, resulting a chimeric reporter prBSEP(-2kb)-hIR1a. Human and rat bsep promoter wt and chimeric reporters were cotransfected with FXRα1 or FXRα2 into Huh 7 cells, followed by treatment of transfected cells with DMSO (0.1%) or CDCA (10 μM) for 30 h. Reporter activities were detected by the dual-luciferase reporter assay system. The data are presented as mean ± SD of at least three repeated experiments. (D) Female CD-1 mice were randomly divided into four groups. Each group of mice was hydrodynamically injected with either phBSEP(-2.6kb), prBSEP(-2kb), phBSEP(-2.6kb)-m/rIR1a, or prBSEP(-2kb)-hIR1a promoter reporter. Luciferase activities as luminescent signals were detected by living imaging IVIS 48 h postinjection and captured by a CCD camera with an exposure of 45 s. (E) BSEP mRNA levels in human and mouse liver tissues were quantified by TaqMan real-time PCR. Using GAPDH mRNA levels as internal standards, the relative mRNA expression levels of BSEP in human and mouse liver tissues were compared. Median value of each group is indicated by a short line. Mann-Whitney nonparametric test was used for pair-wise comparison.

To determine whether the species-specific regulation of BSEP by FXRα1 and FXRα2 is due to the differences in IR1a, two chimeric promoter reporters in which the authentic IR1a was replaced with the IR1a from other species were constructed and tested for their ability to respond to FXRα1 and FXRα2. As shown in Fig. 11B, replacement of the hIR1a in the human BSEP promoter reporter phBSEP(-2.6kb) with m/rIR1a resulted in a strong transactivation of the chimeric promoter reporter phBSEP(2.6kb)-m/rIR1a by both FXRα1 and FXRα2, a pattern comparable to mouse or rat promoter wt (Fig. 1). On the other hand, the reciprocal chimera prBSEP(-2kb)-hIR1a in which the m/rIR1a of rat bsep promoter reporter prBSEP(-2kb) was replaced with human hIR1a exhibited an isoform-dependent transactivation by FXRα1 and FXRα2 as human BSEP promoter wt (Fig. 11C).

To further confirm the results, the wt and chimeric promoter reporters were injected into mice, and their transactivation activities in vivo were evaluated by IVIS living imaging. As shown in Fig. 11D, strong luciferase signals were detected in mice injected with wt rat bsep promoter reporter prBSEP(-2.0kb), while no detectable signals were observed in mice received wt human BSEP promoter reporter phBSEP(-2.6kb), indicating that rat bsep promoter has much stronger activity than human BSEP promoter. Replacement of mouse/rat IR1a with human hIR1a in prBSEP(-2.0kb)-hIR1a markedly reduced the signal compared with wt rat bsep promoter reporter. On the other hand, substitution of the human IR1a with mouse/rat m/rIR1a in phBSEP(-2.6kb)-m/rIR1a resulted in noticeable elevation of luciferase signals compared with wt human BSEP promoter reporter. Taken together, the data firmly established that the sequence differences in IR1a were primarily responsible for the species-specific regulation of BSEP by FXRα1 and FXRα2.

To determine whether the observed differences in BSEP promoter activities between mouse and human is reflected by the endogenous BSEP transcription levels, the BSEP mRNA levels in human and mouse liver tissues were quantified by real-time PCR with GAPDH levels as internal controls. As shown in Fig. 11E, the mRNA level of mouse bsep was significantly higher than that of human BSEP. The data thus demonstrated that mouse bsep was transcribed at a much higher level than human BSEP in vivo.

DISCUSSION

As the limiting step in bile acid enterohepatic circulation, canalicular efflux of bile acids by BSEP is tightly regulated by the bile acids/FXR signaling pathway. In our previous study, it was found that human BSEP was isoform-dependently regulated by FXR, with FXRα2 being the predominant regulator. The relative expression of FXRα1 and FXRα2 was altered in HCC patients and associated with dysregulation of BSEP (25). Similar FXR isoform-dependent transactivation has been reported for other FXR targets, including ileal bile acid-binding protein (24), fibrinogens (26), syndecan-1 (27), and α-crystallin (31). However, it is currently not understood how FXRα1 and FXRα2 exhibit different activity on those FXR targets. Based on EMSA data, it was postulated that FXRα2 had a higher binding affinity than FXRα1 to the FXRE of the targets (24). Such notion is consistent with the fact that the four amino acid residues inserted in FXRα1 are located immediately after the DNA binding domain (DBD). The insertion may alter the conformational structure in DBD, thus compromising its ability to bind to FXRE. However, in this study, we showed that FXRα1 and FXRα2 transactivated human BSEP through two FXREs, IR1b and IR1a, respectively. The question remains how FXRα1-mediated transactivation through IR1b is much weaker than FXRα2-mediated activation through IR1a in human BSEP. One possible explanation is that FXRα1 might have a weaker intrinsic activity than FXRα2. However, such notion is inconsistent with the results that FXRα1 transactivated mouse and rat bsep as potently as did FXRα2 (Fig. 1). Another more likely explanation is that the sequence and/or the content of the IR1b are not optimal for maximal activation by FXRα1.

Considering that FXRα2-mediated transactivation through IR1a is the predominant pathway regulating human BSEP expression, the question remains regarding the physiological significance of FXRα1-mediated transactivation through IR1b in regulating human BSEP. One possible physiological function of FXRα1/IR1b pathway is to support the maximal transactivation of BSEP by the FXRα2/IR1a pathway. Consistent with such speculation are results from the mutational studies that mutation in IR1b markedly reduced FXRα2-mediated basal as well as CDCA-induced transactivation of human BSEP (Fig. 7B). Searching the IR1b sequence in the database revealed that IR1b element is present in many promoter regions (data not shown). However, it remains to be determined whether IR1b element is involved in regulating any of those genes.

Our results showed that in addition to total FXR levels, relative FXR isoform expression levels (FXRα1/FXRα2 ratios) significantly affected human BSEP expression. In healthy human liver tissues, FXRα1/FXRα2 ratios ranged from 1.09 to 1.63, with an average of 1.37, while BSEP expression exhibited 24-fold differences. It was our expectation that as the FXRα1/FXRα2 ratios increased, BSEP expression would decrease. However, the actual data revealed that the relationship between FXRα1/FXRα2 ratio and BSEP expression was dependent on the total FXR expression levels (Fig. 2A, B). As expected, human BSEP expression decreased as the ratios increased at the higher levels of total FXR. However, in contrast to our expectation, BSEP expression increased as the FXRα1/FXRα2 ratio increased at the lower levels of total FXR. We were not able to provide a satisfactory explanation for the relationship exhibited at the lower levels of total FXR. Such phenomenon may be related to FXRα1’s specific activation through IR1b. Since IR1b is completely conserved among species, it is reasonable to speculate that FXRα1-mediated transactivation of human BSEP through IR1b is critical for maintaining BSEP expression in the events of low total FXR levels.

Although FXRα1 abundantly bound to hIR1a and FXRα2 weakly associated with IR1b in vitro in EMSAs (Fig. 8A, C), and FXRα1 competitively decreased FXRα2-mediated transactivation of IR1a reporter (Fig. 10A), it was concluded that FXRα1 and FXRα2 did not bind to hIR1a and IR1b in the full-length promoter content in intact cells, respectively, based on the following considerations: first, recruitments of FXRα1 to hIR1a and FXRα2 to IR1b were not detected in intact cells with the ChIP assays (Fig. 9A, B); second, FXRα1 failed to transactivate hIR1a reporter (Fig. 5A); and third, overexpression of FXRα1 had a negligible effect on FXRα2-mediated transactivation of the full-length promoter (Fig. 10B), indicating no competition between the two for binding to IR1a. Taken together, the data strongly supported the conclusion that FXRα1 and FXRα2 exclusively bind to IR1b and IR1a, respectively, in intact cells. Such discrepancy of FXR binding to FXRE between in vitro and in intact cells indicates that FXR binding to FXRE within cells is governed not only by the sequence but also by the content. Such notion is supported by the finding that among the 1.7 million FXREs predicted in the mouse genome, only 1,656 (32) or 7,794 (30) FXREs were detected for FXR binding in vivo in the liver.

In the ChIP assays, it was noticed that compared with wt promoter, the recruitment of FXRα1 to IR1b in the IR1a mutant or FXRα2 to IR1a in the IR1b mutant was decreased (Fig. 9A, B). One possible explanation for such phenomenon is that mutation in one site has a negative impact on the binding of FXRα1 or FXRα2 to the other site due to the proximity of the two sites (18 bases apart). It should be noted that the ChIP assays were carried out on the transfected wt and mutant promoters. Definitive evidence for FXRα1 binding to IR1b or FXRα2 binding to IR1a in the endogenous BSEP promoter remains to be provided.

In contrast to human BSEP, mouse and rat bsep were comparably transactivated by FXRα1 and FXRα2 (Fig. 1). Mouse and rat m/rIR1a is able to support both FXRα1- and FXRα2-mediated transactivation as the FXRE consensus (FXREc: AGGTCA N TGACCT) does (data not shown). Comparing the sequences of hIR1a, IR1b, and m/rIR1a with FXREc, m/rIR1a is the closest to FXREc, followed by IR1b and hIR1a. Detailed analysis of the sequences revealed that a nucleotide G at position 2 is conserved among FXREc, m/rIR1a, and hIR1a but altered to T in IR1b. Therefore, the G at position 2 may play a determinant role in mediating FXRα2 transactivation. On the other hand, nucleotides A and T in positions 1 and 13 are conserved among FXREc, m/rIR1a, and IR1b, but they are substituted with G and C in hIR1a, suggesting that the A and T in positions 1 and 13 are important for mediating FXRα1 transactivation. In this study, we also identified a half ER2 site immediately upstream of IR1a (Fig. 5C). Characterization of the ER2 half site revealed that it played an important role in achieving maximal transactivation of human BSEP by FXRα2, but the site had no effects on FXRα2-mediated transactivation of rat bsep. Such difference in requirement of ER2 for FXRα2 to achieve maximal BSEP transactivation may relate to the fact that human hIR1a is more remote than mouse/rat m/rIR1a to the FXRE consensus. The imperfect hIR1a needs the half ER2 site to support maximal FXRα2 transactivation, whereas the optimal m/rIR1a alone has the capability of fully supporting FXRα2 transactivation.

In addition to the important role played by FXR in regulating bile acid homeostasis (33, 34), FXR regulates a myriad of other target genes critical for cholesterol, lipid, and glucose homeostasis (34–37), liver regeneration (38), and tumorigenesis (39, 40). Based on our new finding that FXRα1 and FXRα2 transactivated human BSEP through two distinct FXREs, it is reasonable to speculate that FXRα1 and FXRα2 may preferably regulate different sets of FXR target genes involved in various functional pathways. We are currently searching for those FXR isoform-specific target genes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. David Mangelsdorf and Jonathan Reicher for providing human FXRα1 expression plasmid and rat HCC L0 cells, respectively. Technical and instrumental support from the RI-INBRE Core Facility are greatly appreciated.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- BSEP

- bile salt export pump

- CA

- cholic acid

- CDCA

- chenodeoxycholic acid

- ChIP

- chromatin immunoprecipitation

- DCA

- deoxycholic acid

- DIC

- differential interference contrast

- EMSA

- electrophoretic mobility shift assay

- ER2

- everted repeat separated by two nucleotides

- FXR

- farnesoid X receptor

- FXRE

- FXR responsive element

- FXREc

- FXRE consensus

- GDCA

- glycodeoxycholic acid

- GUG

- guggulsterone

- HCC

- hepatocellular carcinoma

- IR1

- inverted repeat with one nucleotide space

- LCA

- lithocholic acid

- NR1H4

- nuclear receptor subfamily 1, group H, member 4

- UDCA

- ursodeoxycholic acid

- wt

- wild-type

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants R01 DK-087755, R01 GM-61988 (B.Y.), and R01 ES-07965 (B.Y.). The RI-INBRE Core Facility is supported by an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institutes of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under Grant 8 P20 GM-103430-12.

REFERENCES

- 1.Meier P. J., Stieger B. 2002. Bile salt transporters. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 64: 635–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kullak-Ublick G. A., Stieger B., Meier P. J. 2004. Enterohepatic bile salt transporters in normal physiology and liver disease. Gastroenterology. 126: 322–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jansen P. L., Strautnieks S. S., Jacquemin E., Hadchouel M., Sokal E. M., Hooiveld G. J., Koning J. H., De Jager-Krikken A., Kuipers F., Stellaard F., et al. 1999. Hepatocanalicular bile salt export pump deficiency in patients with progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis. Gastroenterology. 117: 1370–1379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strautnieks S. S., Bull L. N., Knisely A. S., Kocoshis S. A., Dahl N., Arnell H., Sokal E., Dahan K., Childs S., Ling V., et al. 1998. A gene encoding a liver-specific ABC transporter is mutated in progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis. Nat. Genet. 20: 233–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang L., Soroka C. J., Boyer J. L. 2002. The role of bile salt export pump mutations in progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis type II. J. Clin. Invest. 110: 965–972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scheimann A. O., Strautnieks S. S., Knisely A. S., Byrne J. A., Thompson R. J., Finegold M. J. 2007. Mutations in bile salt export pump (ABCB11) in two children with progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis and cholangiocarcinoma. J. Pediatr. 150: 556–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Mil S. W., van der Woerd W. L., van der Brugge G., Sturm E., Jansen P. L., Bull L. N., van den Berg I. E., Berger R., Houwen R. H., Klomp L. W. 2004. Benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis type 2 is caused by mutations in ABCB11. Gastroenterology. 127: 379–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kubitz R., Keitel V., Scheuring S., Kohrer K., Haussinger D. 2006. Benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis associated with mutations of the bile salt export pump. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 40: 171–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lam C. W., Cheung K. M., Tsui M. S., Yan M. S., Lee C. Y., Tong S. F. 2006. A patient with novel ABCB11 gene mutations with phenotypic transition between BRIC2 and PFIC2. J. Hepatol. 44: 240–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eloranta M. L., Hakli T., Hiltunen M., Helisalmi S., Punnonen K., Heinonen S. 2003. Association of single nucleotide polymorphisms of the bile salt export pump gene with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 38: 648–652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keitel V., Vogt C., Haussinger D., Kubitz R. 2006. Combined mutations of canalicular transporter proteins cause severe intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Gastroenterology. 131: 624–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lang C., Meier Y., Stieger B., Beuers U., Lang T., Kerb R., Kullak-Ublick G. A., Meier P. J., Pauli-Magnus C. 2007. Mutations and polymorphisms in the bile salt export pump and the multidrug resistance protein 3 associated with drug-induced liver injury. Pharmacogenet. Genomics. 17: 47–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knisely A. S., Strautnieks S. S., Meier Y., Stieger B., Byrne J. A., Portmann B. C., Bull L. N., Pawlikowska L., Bilezikci B., Ozcay F., et al. 2006. Hepatocellular carcinoma in ten children under five years of age with bile salt export pump deficiency. Hepatology. 44: 478–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strautnieks S. S., Byrne J. A., Pawlikowska L., Cebecauerova D., Rayner A., Dutton L., Meier Y., Antoniou A., Stieger B., Arnell H., et al. 2008. Severe bile salt export pump deficiency: 82 different ABCB11 mutations in 109 families. Gastroenterology. 134: 1203–1214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ananthanarayanan M., Balasubramanian N., Makishima M., Mangelsdorf D. J., Suchy F. J. 2001. Human bile salt export pump promoter is transactivated by the farnesoid X receptor/bile acid receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 28857–28865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Plass J. R., Mol O., Heegsma J., Geuken M., Faber K. N., Jansen P. L., Muller M. 2002. Farnesoid X receptor and bile salts are involved in transcriptional regulation of the gene encoding the human bile salt export pump. Hepatology. 35: 589–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deng R., Yang D., Radke A., Yang J., Yan B. 2007. The hypolipidemic agent guggulsterone regulates the expression of human bile salt export pump: dominance of transactivation over farsenoid X receptor-mediated antagonism. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 320: 1153–1162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song X., Kaimal R., Yan B., Deng R. 2008. Liver receptor homolog 1 transcriptionally regulates human bile salt export pump expression. J. Lipid Res. 49: 973–984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weerachayaphorn J., Cai S. Y., Soroka C. J., Boyer J. L. 2009. Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 is a positive regulator of human bile salt export pump expression. Hepatology. 50: 1588–1596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parks D. J., Blanchard S. G., Bledsoe R. K., Chandra G., Consler T. G., Kliewer S. A., Stimmel J. B., Willson T. M., Zavacki A. M., Moore D. D., et al. 1999. Bile acids: natural ligands for an orphan nuclear receptor. Science. 284: 1365–1368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Makishima M., Okamoto A. Y., Repa J. J., Tu H., Learned R. M., Luk A., Hull M. V., Lustig K. D., Mangelsdorf D. J., Shan B. 1999. Identification of a nuclear receptor for bile acids. Science. 284: 1362–1365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Otte K., Kranz H., Kober I., Thompson P., Hoefer M., Haubold B., Remmel B., Voss H., Kaiser C., Albers M., et al. 2003. Identification of farnesoid X receptor beta as a novel mammalian nuclear receptor sensing lanosterol. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23: 864–872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huber R. M., Murphy K., Miao B., Link J. R., Cunningham M. R., Rupar M. J., Gunyuzlu P. L., Haws T. F., Kassam A., Powell F., et al. 2002. Generation of multiple farnesoid-X-receptor isoforms through the use of alternative promoters. Gene. 290: 35–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Y., Kast-Woelbern H. R., Edwards P. A. 2003. Natural structural variants of the nuclear receptor farnesoid X receptor affect transcriptional activation. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 104–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Y., Song X., Valanejad L., Vasilenko A., More V., Qiu X., Chen W., Lai Y., Slitt A., Stoner M., et al. 2013. Bile salt export pump is dysregulated with altered farnesoid X receptor isoform expression in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 57: 1530–1541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anisfeld A. M., Kast-Woelbern H. R., Lee H., Zhang Y., Lee F. Y., Edwards P. A. 2005. Activation of the nuclear receptor FXR induces fibrinogen expression: a new role for bile acid signaling. J. Lipid Res. 46: 458–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anisfeld A. M., Kast-Woelbern H. R., Meyer M. E., Jones S. A., Zhang Y., Williams K. J., Willson T., Edwards P. A. 2003. Syndecan-1 expression is regulated in an isoform-specific manner by the farnesoid-X receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 20420–20428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deng R., Yang D., Yang J., Yan B. 2006. Oxysterol 22(R)-hydroxycholesterol induces the expression of the bile salt export pump through nuclear receptor farsenoid X receptor but not liver X receptor. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 317: 317–325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaimal R., Song X., Yan B., King R., Deng R. 2009. Differential modulation of farnesoid X receptor signaling pathway by the thiazolidinediones. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 330: 125–134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomas A. M., Hart S. N., Kong B., Fang J., Zhong X. B., Guo G. L. 2010. Genome-wide tissue-specific farnesoid X receptor binding in mouse liver and intestine. Hepatology. 51: 1410–1419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee F. Y., Kast-Woelbern H. R., Chang J., Luo G., Jones S. A., Fishbein M. C., Edwards P. A. 2005. Alpha-crystallin is a target gene of the farnesoid X-activated receptor in human livers. J. Biol. Chem. 280: 31792–31800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chong H. K., Infante A. M., Seo Y. K., Jeon T. I., Zhang Y., Edwards P. A., Xie X., Osborne T. F. 2010. Genome-wide interrogation of hepatic FXR reveals an asymmetric IR-1 motif and synergy with LRH-1. Nucleic Acids Res. 38: 6007–6017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sinal C. J., Tohkin M., Miyata M., Ward J. M., Lambert G., Gonzalez F. J. 2000. Targeted disruption of the nuclear receptor FXR/BAR impairs bile acid and lipid homeostasis. Cell. 102: 731–744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eloranta J. J., Kullak-Ublick G. A. 2008. The role of FXR in disorders of bile acid homeostasis. Physiology (Bethesda). 23: 286–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Y., Edwards P. A. 2008. FXR signaling in metabolic disease. FEBS Lett. 582: 10–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kalaany N. Y., Mangelsdorf D. J. 2006. LXRS and FXR: the yin and yang of cholesterol and fat metabolism. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 68: 159–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Claudel T., Staels B., Kuipers F. 2005. The farnesoid X receptor: a molecular link between bile acid and lipid and glucose metabolism. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 25: 2020–2030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang W., Ma K., Zhang J., Qatanani M., Cuvillier J., Liu J., Dong B., Huang X., Moore D. D. 2006. Nuclear receptor-dependent bile acid signaling is required for normal liver regeneration. Science. 312: 233–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang F., Huang X., Yi T., Yen Y., Moore D. D., Huang W. 2007. Spontaneous development of liver tumors in the absence of the bile acid receptor farnesoid X receptor. Cancer Res. 67: 863–867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim I., Morimura K., Shah Y., Yang Q., Ward J. M., Gonzalez F. J. 2007. Spontaneous hepatocarcinogenesis in farnesoid X receptor-null mice. Carcinogenesis. 28: 940–946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]