Abstract

131I is widely used for therapy in the clinic and 125I and 131I, and increasingly 211At, are often used in experimental studies. It is important to know the biodistribution and dosimetry for these radionuclides to determine potential risk organs when using radiopharmaceuticals containing these radionuclides. The purpose of this study was to investigate the biodistribution of 125I−, 131I−, and free 211At in rats and to determine absorbed doses to various organs and tissues. Male Sprague Dawley rats were injected simultaneously with 0.1–0.3 MBq 125I− and 0.1–0.3 MBq 131I−, or 0.05–0.2 MBq 211At and sacrificed 1 hour to 7 days after injection. The activities and activity concentrations in organs and tissues were determined and mean absorbed doses were calculated. The biodistribution of 125I− was similar to that of 131I− but the biodistribution of free 211At was different compared to 125I− and 131I−. The activity concentration of radioiodine was higher compared with 211At in the thyroid and lower in all extrathyroidal tissues. The mean absorbed dose per unit injected activity was highest to the thyroid. 131I gave the highest absorbed dose to the thyroid, and 211At gave the highest absorbed dose to all other tissues studied.

Key words: 125I−, 131I−, 211At, biodistribution, dosimetry

Introduction

Radioactive iodine has long been used for medical purposes. 131I is the radionuclide most widely used for treatment of various thyroid disorders, such as hyperthyroidism and thyroid cancer. This is due to the fact that iodide mainly accumulates in the thyroid gland and in differentiated thyroid carcinoma cells, but also since 131I has decay properties favorable for treatment. Iodine is transported into the thyroid follicular cells by the sodium iodide symporter (NIS).1

Astatine is the heaviest of the halogens, the chemical group also containing iodine. Astatine is thought to have properties similar to iodine in regard to thyroid uptake and excretion, for example, 211At is probably transported partly by NIS,2,3 although 211At seems to have metallic properties resembling those of polonium.4,5 Due to an assumed near optimal LET for therapy 211At is very suitable for therapeutic applications.6 211At emits, for example, α-particles with a very short range in tissue compared to most of the electrons emitted by 131I, together with a lower photon emission.

Animal models are often used to test new radiopharmaceuticals for treatment of tumor diseases, including both mice and rats. This is an important area of research to improve already existing and new treatment methods, especially for disseminated tumor disease, when using radioactive substances labeled with 131I or 211At. It is common that a small amount of 131I− or free 211At is released from the radiopharmaceutical in vivo. It is then important to know the biodistribution and the absorbed dose to normal tissues for 131I and 211At to determine potential risk organs when using such radiopharmaceuticals for treatment. To our knowledge, no biodistribution data of free 211At can be found in humans. For pharmaceuticals directly labeled with radioiodine the released iodine will most probably be in the iodide chemical form. For indirectly iodinated pharmaceuticals, the chemical form of the released radioiodine might vary. For astatine At− is the best defined valence state and it is expected to be stable in acidic and basic solutions containing reducing agents.7 However, to our knowledge no information can be found on the behavior of At− in solutions without reducing agents. In this article, we therefore, use the term “free astatine” to include all possible oxidation states of astatine occurring in vivo.

The biodistribution of 125I−, 131I− and free 211At has been studied in mice.8–12 The results demonstrate clear differences between the radionuclides and show a higher accumulation of 211At compared to radioiodine in all organs and tissues except the thyroid. The difference in size between rats and mice makes organ sampling easier in rats, particularly for the smaller organs (such as thyroid which is one of the risk organs), which can be difficult to entirely excise alone in mice. This may result in a more extensive use of rat animal models. To our knowledge, biodistribution data of iodide and free 211At in rats has been presented in only one article, published in 1953.13 There is thus, a need to repeat such a study. Furthermore, at that time the astatine chemistry was only known to some extent.

The purpose of this study was to investigate and compare the biokinetics of 125I−, 131I−, and free 211At in rats and to determine absorbed doses from these radionuclides to various organs and tissues.

Materials and Methods

Animal model

Male Sprague Dawley rats (Scanbur AB) weighing 180–210 g were used in all studies. The rats were kept in groups of 5 individuals per cage. Drinking water and autoclaved food were given ad libitum. For 5 days, before injection, the animals were given autoclaved food with reduced iodine content (0.05 ppm), at all other times it was regular autoclaved laboratory food (iodine content 2 ppm). The studies were approved by the Ethics committee for Animal Research at University of Gothenburg.

Radionuclides

125I was delivered (as NaI) from PerkinElmer and 131I was delivered (as NaI) from GE Healthcare. 211At was produced through the 209Bi(α,2n)211At reaction and delivered from the Cyclotron and PET Unit at Rigshospitalet in Copenhagen, Denmark. The extraction procedure of the 211At has previously been presented.14 Throughout this article, 211At refers to “free astatine” which probably consists not only of 211At− but also, to some extent, of other oxidation states.

The decay data for 125I, 131I and 211At is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Decay Data for 125I, 131I, and 211At17

| |

|

|

Energy per decay (keV/Bq·s) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radionuclide | Decay mode | T1/2 | Electrons | α-Particles | Photons |

| 125I | EC | 59 days | 17 | — | 42 |

| 131I | β− | 8.0 days | 190 | — | 380 |

| 211At | α, EC | 7.2 hours | 0.048 | 6900 | 27 |

α-particle data for 211At was calculated from the complex disintegration of 211At and 211Po.

Administration and organ sampling

Radioactive solutions were prepared using sodium radioiodide dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.2). The syringes and needles were weighed individually before and after adding the solution, and also after injection, to determine the amount of radioactive solution administered. The rats were divided into two study groups. The first study comprised of 30 animals, which were further divided into six groups with 5 animals in each group. These were injected intravenously with 0.1–0.3 MBq 125I− and 0.1–0.3 MBq 131I− in 0.15 mL of PBS. The rats were sacrificed by cardiac puncture under anaesthesia with Mebumal (sodium pentobarbital 60 mg/mL; Apoteksbolaget AB) at 1, 6, 18, 24, 72 hours, or 7 days after injection. The animals were immediately dissected and radioactivity measurements were made ex vivo on trachea (including thyroid), salivary glands, blood (0.5–1 mL, from cardiac puncture), lungs, heart, liver (right lobe), kidney (right), stomach, muscle from neck, brain, spleen, and sections of large and small intestine.

The second study involved 20 rats divided into four groups with five animals in each group and injected with 0.05–0.2 MBq 211At in 0.15 mL of PBS. Also here, the syringes and needles were weighed individually before and after adding the solution, and also after injection. The rats were sacrificed as described above at 1, 5, 18, or 24 hours after injection. The animals were immediately dissected and all tissue samples were weighed. Radioactivity measurements were made ex vivo on thyroid, salivary glands, blood (1 mL, from cardiac puncture), lungs, heart, liver (right lobe), kidney (right), stomach, muscle from neck, spleen, and sections of large and small intestine.

Radioactivity measurements

Injected activity was individually determined by measurements on the syringes before injection using an ion chamber (CRC-15 dose calibrator; Capintec), and also by measuring syringe remnants and batch solutions in a gamma-counter (Wallac 1480 WIZARD® 3′′; Wallac Oy). Radioactivity measurements made ex vivo on the rat organs were performed using the gamma-counter. Corrections were made for dead time loss, self-attenuation, spill-over (when performing measurements on 125I and 131I simultaneously), radioactive decay, and background. The measurement time was adjusted to allow the counts in the sample to exceed 1000 counts above the background level; this resulted in a detection error, which was less than 3%.

The activities in the organs and tissues at time t, atissue(t), were calculated as percent of the injected activity (%IA):

|

Eq. 1 |

and the activity concentrations at time t, ctissue(t), as percent of the injected activity per gram tissue (%IA/g):

|

Eq. 2 |

where Atissue(t) is the activity in the sample at time t corrected for radioactive decay to t=0, Ainj is the activity injected at time t=0, and mtissue is the mass of the tissue sample.

The total blood volume (in mL) of the animal, Vblood, was determined using

|

Eq. 3 |

where mbody is the body weight in grams.15

For those tissues where the entire organ was not measured (blood, liver, small intestine and large intestine), calculations of atissue(t) were performed by correcting Atissue(t) to correspond to the whole of the organ (assuming homologous activity distribution inside the organ). The total organ mass was calculated using previous measurements.13,15 When calculating the cthyroid(t) from the trachea sample (including thyroid) it was assumed that the trachea had no uptake of iodine and the weight used in this calculation was the mean weight of the thyroids collected in the second study.

Absorbed dose calculations

The mean absorbed dose to the various organs and tissues from the different radionuclides was calculated according to the Medical Internal Radiation Dose (MIRD) formalism:

|

Eq. 4 |

where Ãtissue is the cumulated activity in the organ, E is the mean emitted energy per disintegration and ø is the absorbed fraction. For absorbed dose calculations on thyroids containing radioiodine, the mean weight of the thyroids collected in the biodistribution study of 211At was used.

Ãtissue was calculated from the data using

|

Eq. 5 |

where tD is the time to which the absorbed dose contribution is to be calculated, and λ is the radioactivity decay constant. Due to the short range of α-particles and electrons compared to the size of most of the rat organs, the self-absorbed fraction was set to 1.0 for 125I and 211At. For 131I the self-absorbed fraction was calculated from previously presented results.16 The cross-absorbed fraction was set to 0 for all organs for all three radionuclides. The activity distribution in the source-organs was assumed to be homogeneous.

E was assumed to include only the electrons emitted for the radioiodine isotopes, and for 211At E was assumed to concern only the α-disintegrations and was calculated from the complex disintegration of 211At and 211Po (Table 1).17 Table 1 also shows the contribution calculated from the EC disintegration chain of 211At to 207Bi.

Statistical analysis

The statistical uncertainties in the measurements are represented by standard error of the mean (SEM).

Results

Biodistribution of 125I−, 131I− and 211At

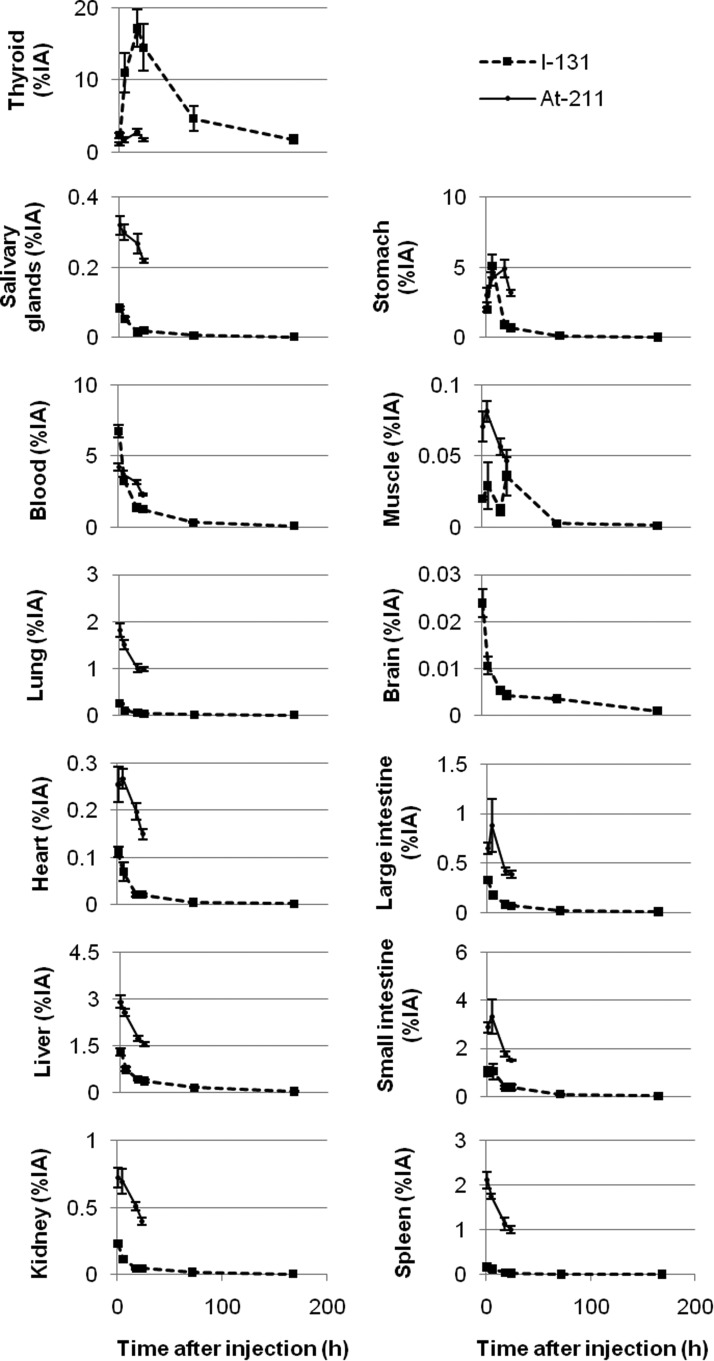

The biodistribution of 125I− and 131I− was determined 1 hour to 7 days after injection [Table 2 shows ctissue(t), and Fig. 1 shows atissue(t)], and the biodistribution of 211At was determined 1–24 hours after injection [ctissue(t) is shown in Table 3, and atissue(t) in Fig. 1]. The biodistribution of 125I− was similar to that of 131I− and only the data from 131I− is shown in Figure 1. The thyroid gland showed the highest accumulation of all three radionuclides with athyroid=16%IA (SEM=1.5%IA) or cthyroid=400%IA/g (SEM=40%IA/g) for 125I, while for 131I the uptake was 17%IA (SEM=2.6%IA) or 430%IA/g (SEM=60%IA/g), and for 211At 2.8%IA (SEM=0.5%IA) or 75%IA/g (SEM=15%IA/g) after 18 hours. For thyroid, the activity concentration was highest at 18 hours for all three radionuclides. In all organs and tissues except the thyroid, the activity concentration of 211At was higher compared with 125I− and 131I−. This was particularly evident for lungs and spleen. 211At was also retained longer in extrathyroidal tissues compared to 125I− and 131I−. The stomach, which is known to express NIS,18 had a high concentration of all three radionuclides. The activity concentration in the stomach was highest after 6 hours for 125I− and 131I− and after 18 hours for 211At. The brain had the lowest activity concentration of radioiodine of all organs and tissues studied.

Table 2.

The Activity Concentration [ctissue(t)], %IA/g, of 125I− and 131I− in Rats (n=5) at 1 Hour to 7 Days After Simultaneous Injection of 0.1–0.3 MBq of 125I− and 0.1–0.3 MBq of 131I−

| |

ctissue(t) (%IA/g) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue | 1 hour | 6 hours | 18 hours | 24 hours | 72 hours | 7 days |

| 125I− | ||||||

| Blood | 0.44 (0.02) | 0.26 (0.02) | 0.09 (0.01) | 0.10 (0.01) | 0.023 (0.002) | 0.006 (0.001) |

| Brain | 0.023 (0.003) | 0.018 (0.003) | 0.007 (0.001) | 0.009 (0.002) | 0.0042 (0.0004) | 0.0007 (0.0001) |

| Heart | 0.150 (0.003) | 0.13 (0.02) | 0.035 (0.005) | 0.039 (0.005) | 0.011 (0.001) | 0.0028 (0.0005) |

| Kidneys | 0.30 (0.01) | 0.19 (0.02) | 0.07 (0.01) | 0.07 (0.01) | 0.023 (0.002) | 0.007 (0.001) |

| Large intestine | 0.22 (0.02) | 0.16 (0.01) | 0.05 (0.01) | 0.05 (0.01) | 0.012 (0.003) | 0.0035 (0.0005) |

| Liver | 0.18 (0.01) | 0.12 (0.01) | 0.056 (0.003) | 0.06 (0.01) | 0.025 (0.003) | 0.007 (0.001) |

| Lungs | 0.29 (0.01) | 0.27 (0.07) | 0.11 (0.01) | 0.07 (0.01) | 0.019 (0.002) | 0.0057 (0.0004) |

| Muscle | 0.081 (0.004) | 0.15 (0.09) | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.14 (0.05) | 0.011 (0.003) | 0.005 (0.001) |

| Salivary glands | 0.19 (0.01) | 0.15 (0.02) | 0.05 (0.01) | 0.07 (0.01) | 0.017 (0.002) | 0.005 (0.001) |

| Small intestine | 0.28 (0.04) | 0.37 (0.12) | 0.10 (0.02) | 0.13 (0.04) | 0.024 (0.003) | 0.004 (0.001) |

| Spleen | 0.20 (0.02) | 0.25 (0.11) | 0.044 (0.003) | 0.04 (0.01) | 0.011 (0.002) | 0.0029 (0.0003) |

| Stomach | 1.2 (0.1) | 4.1 (0.6) | 0.61 (0.12) | 0.64 (0.13) | 0.10 (0.01) | 0.006 (0.001) |

| Thyroid | 50 (6) | 270 (60) | 400 (40) | 340 (40) | 110 (40) | 40 (14) |

| 131I− | ||||||

| Blood | 0.46 (0.03) | 0.22 (0.02) | 0.09 (0.01) | 0.09 (0.01) | 0.022 (0.002) | 0.006 (0.001) |

| Brain | 0.025 (0.003) | 0.017 (0.003) | 0.007 (0.001) | 0.008 (0.001) | 0.0045 (0.0004) | 0.0011 (0.0001) |

| Heart | 0.16 (0.01) | 0.11 (0.02) | 0.039 (0.005) | 0.036 (0.004) | 0.010 (0.002) | 0.0030 (0.0005) |

| Kidneys | 0.27 (0.02) | 0.17 (0.02) | 0.07 (0.01) | 0.06 (0.01) | 0.023 (0.002) | 0.007 (0.001) |

| Large intestine | 0.23 (0.02) | 0.13 (0.01) | 0.06 (0.01) | 0.046 (0.004) | 0.011 (0.003) | 0.0035 (0.0004) |

| Liver | 0.18 (0.02) | 0.11 (0.01) | 0.059 (0.005) | 0.05 (0.01) | 0.024 (0.003) | 0.007 (0.001) |

| Lungs | 0.32 (0.02) | 0.18 (0.03) | 0.07 (0.01) | 0.06 (0.01) | 0.019 (0.002) | 0.0061 (0.0005) |

| Muscle | 0.09 (0.01) | 0.14 (0.08) | 0.05 (0.01) | 0.13 (0.05) | 0.012 (0.003) | 0.005 (0.001) |

| Salivary glands | 0.20 (0.02) | 0.13 (0.02) | 0.047 (0.005) | 0.07 (0.02) | 0.017 (0.002) | 0.005 (0.001) |

| Small intestine | 0.30 (0.05) | 0.30 (0.10) | 0.11 (0.02) | 0.11 (0.03) | 0.025 (0.003) | 0.004 (0.001) |

| Spleen | 0.22 (0.03) | 0.19 (0.08) | 0.045 (0.005) | 0.036 (0.004) | 0.011 (0.002) | 0.0031 (0.0004) |

| Stomach | 1.2 (0.1) | 3.9 (0.6) | 0.62 (0.12) | 0.54 (0.09) | 0.10 (0.01) | 0.006 (0.001) |

| Thyroid | 50 (9) | 270 (70) | 430 (60) | 360 (80) | 110 (40) | 40 (14) |

Data are given as the mean (SEM). The data are corrected for physical decay.

SEM, standard error of the mean.

FIG. 1.

The mean activity [atissue(t)], %IA, of 131I− and 211At in rats (n=5) at 1 hour to 7 days after simultaneous injection of 0.1–0.3 MBq 125I− and 0.1–0.3 MBq 131I or 0.05–0.2 MBq of 211At. Data are given as the mean±standard error of the mean. The data from 125I− was similar to that of 131I−.

Table 3.

The Activity Concentration [ctissue(t)], %IA/g, of 211At in Rats (n=5) at 1–24 Hours After Injection of 0.05–0.2 MBq of 211At

| |

ctissue, At-211(t) (%IA/g) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue | 1 hour | 5 hours | 18 hours | 24 hours |

| Blood | 0.29 (0.02) | 0.26 (0.01) | 0.22 (0.01) | 0.160 (0.005) |

| Heart | 0.53 (0.04) | 0.49 (0.03) | 0.34 (0.01) | 0.29 (0.01) |

| Kidneys | 1.2 (0.1) | 1.1 (0.1) | 0.72 (0.04) | 0.61 (0.02) |

| Large intestine | 0.46 (0.04) | 0.63 (0.19) | 0.30 (0.02) | 0.28 (0.03) |

| Liver | 0.41 (0.03) | 0.36 (0.02) | 0.25 (0.01) | 0.22 (0.01) |

| Lungs | 3.0 (0.2) | 2.50 (0.05) | 1.8 (0.1) | 1.60 (0.03) |

| Muscle | 0.32 (0.04) | 0.34 (0.05) | 0.24 (0.02) | 0.23 (0.04) |

| Salivary glands | 0.95 (0.11) | 0.76 (0.03) | 0.52 (0.01) | 0.47 (0.02) |

| Small intestine | 0.82 (0.06) | 0.95 (0.21) | 0.50 (0.03) | 0.43 (0.01) |

| Spleen | 3.0 (0.2) | 2.4 (0.1) | 1.7 (0.1) | 1.5 (0.1) |

| Stomach | 2.3 (0.4) | 3.1 (0.3) | 3.6 (0.5) | 2.4 (0.2) |

| Thyroid | 35 (9) | 41 (11) | 75 (15) | 37 (3) |

Data are given as the mean (SEM). The data are corrected for physical decay.

Dosimetry

The dosimetric calculations for 125I, 131I, and 211At show that the thyroid received the highest absorbed dose per injected activity, with Dthyroid, I-125=2600 mGy/MBq and Dthyroid, I-131=21000 mGy/MBq (Table 4) and Dthyroid, At-211=18000 mGy/MBq (Table 5) at t=∞. The highest mean absorbed doses to extrathyroidal tissues and organs were found in stomach, heart, and small intestine for 125I and 131I, and in stomach, lungs and spleen for 211At. 211At delivered a much higher absorbed dose per injected activity to all extrathyroidal organs compared to 125I and 131I (at t=∞), and 125I delivered the lowest absorbed dose per unit injected activity.

Table 4.

The Mean Absorbed Dose Per Unit Injected Activity, mGy/MBq, of 125I and 131I in Rats Obtained at Different Points in Time After Injection (n=5) and the Corresponding mtissue Used for Calculations (n=30)

| |

|

D(t) (mGy/MBq) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue | mtissue(g) | 18 hours | 24 hours | 72 hours | 7 days | ∞ |

| 125I | ||||||

| Blood | 0.67 (0.01) | 0.40 (0.01) | 0.46 (0.01) | 0.72 (0.04) | 0.85 (0.05) | 0.87 (0.05) |

| Brain | 0.76 (0.04) | 0.027 (0.002) | 0.033 (0.002) | 0.05 (0.01) | 0.08 (0.01) | 0.08 (0.01) |

| Heart | 0.59 (0.02) | 1.3 (0.1) | 1.3 (0.1) | 1.4 (0.1) | 1.5 (0.1) | 1.5 (0.1) |

| Kidney | 0.71 (0.02) | 0.30 (0.02) | 0.34 (0.02) | 0.56 (0.03) | 0.70 (0.04) | 0.74 (0.04) |

| Large intestine | 0.33 (0.01) | 0.20 (0.02) | 0.23 (0.02) | 0.38 (0.03) | 0.44 (0.04) | 0.46 (0.03) |

| Liver | 1.95 (0.05) | 0.18 (0.01) | 0.22 (0.01) | 0.45 (0.03) | 0.58 (0.04) | 0.61 (0.04) |

| Lung | 0.66 (0.03) | 0.34 (0.08) | 0.40 (0.09) | 0.61 (0.08) | 0.70 (0.08) | 0.73 (0.08) |

| Muscle | 0.23 (0.01) | 0.15 (0.05) | 0.21 (0.05) | 0.63 (0.15) | 0.74 (0.15) | 0.76 (0.15) |

| Salivary glands | 0.36 (0.01) | 0.22 (0.02) | 0.26 (0.02) | 0.44 (0.05) | 0.55 (0.05) | 0.57 (0.05) |

| Small intestine | 0.74 (0.02) | 0.39 (0.08) | 0.46 (0.08) | 0.89 (0.20) | 1.0 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.2) |

| Spleen | 0.71 (0.02) | 0.25 (0.06) | 0.28 (0.06) | 0.40 (0.08) | 0.46 (0.08) | 0.48 (0.08) |

| Stomach | 1.41 (0.03) | 3.9 (0.4) | 4.3 (0.4) | 5.9 (0.5) | 6.3 (0.5) | 6.3 (0.5) |

| Thyroid | 0.040 (0.002) | 470 (60) | 680 (80) | 1700 (100) | 2400 (200) | 2600 (300) |

| 131I | ||||||

| Blood | 0.67 (0.01) | 4.4 (0.1) | 5.0 (0.1) | 7.4 (0.3) | 8.5 (0.4) | 8.6 (0.4) |

| Brain | 0.76 (0.04) | 0.30 (0.02) | 0.36 (0.02) | 0.58 (0.04) | 0.78 (0.07) | 0.82 (0.07) |

| Heart | 0.59 (0.02) | 13 (1) | 14 (1) | 15 (1) | 16 (1) | 16 (1) |

| Kidney | 0.71 (0.02) | 3.0 (0.2) | 3.4 (0.2) | 5.6 (0.2) | 6.8 (0.3) | 7.0 (0.4) |

| Large intestine | 0.33 (0.01) | 2.1 (0.1) | 2.4 (0.1) | 3.7 (0.2) | 4.1 (0.2) | 4.2 (0.2) |

| Liver | 1.95 (0.05) | 2.1 (0.1) | 2.4 (0.1) | 4.5 (0.3) | 5.7 (0.4) | 5.9 (0.4) |

| Lung | 0.66 (0.03) | 3.2 (0.3) | 3.6 (0.3) | 5.5 (0.3) | 6.3 (0.3) | 6.5 (0.3) |

| Muscle | 0.23 (0.01) | 1.5 (0.5) | 2.0 (0.4) | 5.8 (1.2) | 7.0 (1.2) | 7.1 (1.2) |

| Salivary glands | 0.36 (0.01) | 2.2 (0.2) | 2.5 (0.3) | 4.1 (0.5) | 4.9 (0.5) | 5.0 (0.5) |

| Small intestine | 0.74 (0.02) | 4.2 (0.8) | 4.9 (0.9) | 8.8 (2.0) | 10 (2) | 10 (2) |

| Spleen | 0.71 (0.02) | 2.5 (0.5) | 2.8 (0.5) | 3.9 (0.7) | 4.5 (0.6) | 4.6 (0.6) |

| Stomach | 1.41 (0.03) | 41 (4) | 45 (4) | 60 (5) | 64 (5) | 64 (5) |

| Thyroid | 0.040 (0.002) | 4200 (700) | 6100 (800) | 15000 (2000) | 19000 (2000) | 21000 (2000) |

Data are given as the mean (SEM).

Table 5.

The Mean Absorbed Dose Per Unit Injected Activity, mGy/MBq, of 211At in Rats Obtained at Different Points in Time After Injection (n=5) and the Corresponding mtissue Used for Calculations (n=20)

| |

|

D(t) (mGy/MBq) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue | mtissue(g) | 18 hours | 24 hours | ∞ |

| Blood | 0.96 (0.04) | 87 (3) | 93 (3) | 98 (3) |

| Heart | 0.53 (0.02) | 170 (10) | 180 (10) | 190 (20) |

| Kidney | 0.65 (0.02) | 370 (20) | 390 (20) | 390 (20) |

| Large intestine | 0.35 (0.01) | 200 (40) | 210 (40) | 210 (40) |

| Liver | 1.97 (0.08) | 160 (10) | 160 (10) | 230 (20) |

| Lung | 0.60 (0.01) | 1000 (100) | 1100 (100) | 1100 (100) |

| Muscle | 0.23 (0.01) | 120 (10) | 120 (10) | 130 (10) |

| Salivary glands | 0.43 (0.02) | 250 (10) | 270 (10) | 280 (10) |

| Small intestine | 0.78 (0.02) | 310 (50) | 330 (50) | 340 (50) |

| Spleen | 0.69 (0.02) | 950 (50) | 1000 (50) | 1000 (50) |

| Stomach | 1.33 (0.02) | 1000 (100) | 1200 (100) | 1200 (100) |

| Thyroid | 0.040 (0.002) | 16000 (4000) | 17000 (4000) | 18000 (4000) |

Data are given as the mean (SEM).

Discussion

No significant difference was found between the biodistributions of 125I− and 131I− (Table 2). This was expected since the very small difference in atomic mass should not have an impact on the biokinetics of a radionuclide. Results showed that the trachea (including thyroid) and stomach selectively accumulated iodide over time (Table 2 and Fig. 1). This was also true for 211At (Table 3 and Fig. 1) and was expected since both organs are known to express NIS.18 The higher concentration of 125I− and 131I− than 211At in thyroid could only to a low extent be explained by the difference in thyroid tissue sampling technique between the studies (a possible overestimation of 125I− and 131I− concentration). No other organs showed significant increase in activity concentration from 1 to 5–6 hours after injection. The salivary glands, which are also known to express NIS,18 showed low activity concentrations of all three radionuclides. The biodistribution of 211At also showed high activity concentrations in lungs and spleen and to a lesser extent in the kidneys. This supports our previous findings that the uptake/transport of 211At is also dependent on mechanisms other than NIS.3 Results also showed that the retention time of 211At was longer compared with125I− and 131I−. A possible explanation for this is that the biochemical properties of 211At in vivo, which are largely unknown, might change after injection. Another possibility is the existence of an uptake mechanism different from NIS.

Two animals showed unexpectedly low activity concentrations of both 125I− and 131I− in the thyroid at 6 and 72 hours and 7 days and resulted in high SEM values for these time points (Table 2). No obvious abnormalities could be found in these individuals, and the activity concentrations in other organs and tissues did not differ. A possible reason is that the animals in question had a slower metabolic rate. The individual food intake of the animals was not monitored and differences might change the amount of stable iodine accumulated in the thyroid before injection with radioiodide. Results from our pilot studies without the reduced iodine diet showed similar unexpectedly low activity concentrations of radioiodide, but in a larger number of animals (data not shown). The findings might be explained by the relatively high iodine concentration (2 ppm) in regular laboratory food compared to normal human diets (about 0.1 ppm). Therefore, the food with reduced iodine content (0.05 ppm), which better resembles a normal human diet was used, which seems to have reduced the effect.

In the previous study, from 1953 on female Long-Evans rats kept on standard laboratory chow, the maximum uptake in thyroid for 131I and 211At occurred 24 hours after injection.13 In the present study, the maximum activity of 131I found in the thyroid was about half of the maximum activity found by Hamilton et al. (17%IA compared to 28%IA), although our rats had probably received food with lower iodide content (the iodide content was not specified in the older study). Similar relations (lower concentrations in the present study) were found for most of the other organs and tissues (except spleen which had a similar maximum uptake). The reason for this discrepancy is not known; however, the most possible explanation is differences in stable iodine intake via the food and rat strain. The differences in sex and amount of administered 131I (0.1–0.3 vs. 1.4 MBq) would most probably not affect the biodistribution. In the older study no organs or tissues except the thyroid gland showed a selective accumulation of radioiodide over time. This is in contrast to the results found in the present study, which also showed a selective accumulation in the stomach.

The maximum activity of 211At found in the thyroid in the older study was about one-tenth of the maximum activity of radioiodide, while it was about one-fifth in the present study. The maximum activity of 211At in the thyroid in our study (at 18 hours) was similar to that found previously (at 24 hours), (2.8%IA compared to 2.7%IA). For the other organs and tissues, the older study gave somewhat higher maximum activities in general. In both studies, only the thyroid gland and the stomach showed selective accumulation of 211At over time.

In a third limited study from 1954, the thyroidal uptake of 211At was 1.2%IA 1.5 hours after injection.19 This is comparable to the results found in the present study (1.1%IA 1 hour after injection).

Studies on the biodistribution of 211At in nude mice11,12 have shown that the uptake of 211At was highest in the thyroid gland, lungs, spleen, and stomach. These studies also demonstrated higher activity concentrations of 211At compared to radioiodine in extrathyroidal organs and tissues and Lundh et al.12 also showed a longer retention time of 211At compared to 125I−. These results are all in accordance with the results found in this study. In contrast to the results found in this study, previous studies on nude mice present a maximum thyroidal uptake of 211At at approximately 4 hours after injection.10,12 The reason for this difference is probably due to lower metabolic rates in rats compared to mice.20

In the dosimetric calculations, only the electrons and α-particles were considered (see Table 1 for decay data). This assumes no photon contribution to the absorbed dose and resulted only in a small underestimation of the absorbed dose. Previous studies have shown that the photon absorbed dose contribution is, for example, about 7% for the mouse thyroid gland for 125I.21 Concerning 211At the energy released from electrons and photons per decay is negligible compared to that from the alpha particles. However, these results are from animal models and a translation of this data to the human system must be performed with caution, for all three radionuclides, as the photon contribution may be higher in clinical situations.22,23

Results from the absorbed dose calculations showed that the thyroid received the maximum mean absorbed dose per unit injected activity, for all three radionuclides (Tables 4 and 5). This was expected due to the high activity concentration (400%IA/g for 125I−, 430%IA/g for 131I− and 75%IA/g for 211At). The highest mean absorbed dose per unit injected activity to the thyroid was found for 131I followed by 211At (2.1·104 mGy/MBq compared to 1.8·104 mGy/MBq, values compared at t=∞), which is explained by the much higher activity concentrations found for 131I− and the much shorter half-life of 211At. For the other organs and tissues 211At delivered a higher absorbed dose per unit injected activity in general, due to the larger amount of energy deposited per disintegration and longer retention time of 211At compared to 125I− and 131I−. In a clinical application, the tissue accumulation of 211At may be blocked, which would potentially reduce the mean absorbed dose to extrathyroidal tissue.11

Conclusions

The biodistribution of free 211At is different compared to 125I− and 131I−. The thyroid gland was found to accumulate 125I−, 131I−, and 211At selectively, although the activity concentration of 211At was only about one-fifth of that of radioiodide. Absorbed dose calculations showed that 211At gave the highest mean absorbed dose per unit injected activity to all extrathyroidal tissues.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Lilian Karlsson for her skillful handling of the animals and Dr. Sture Lindegren for the generous supply of 211At. This study was supported by grants from the European Commission FP7 Collaborative Project TARCC HEALTH-F2-2007-201962, the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Cancer Society, BioCARE—a National Strategic Research Program at University of Gothenburg, the Swedish Radiation Safety Authority and the King Gustav V Jubilee Clinic Cancer Research Foundation. The work was performed within the EC COST Action BM0607.

Disclosure Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Dohan O. De la Vieja A. Paroder V, et al. The sodium/iodide symporter (NIS): Characterization, regulation, and medical significance. Endocr Rev. 2003;24:48. doi: 10.1210/er.2001-0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamilton JG. Soley MH. A comparison of the metabolism of iodine and of element 85 (eka-iodine) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1940;26:483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.26.8.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindencrona U. Nilsson M. Forssell-Aronsson E. Similarities and differences between free 211At and 125I- transport in porcine thyroid epithelial cells cultured in bicameral chambers. Nucl Med Biol. 2001;28:41. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(00)00179-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corson DR. Mackenzie KR. Segré E. Artificially radioactive element 85. Phys Rev. 1940;58:672. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Visser GWM. Diemer EL. The synthesis of organic at-compounds through thallium compounds. Int J Appl Radiat Isot. 1982;33:389. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown I. Astatine-211: Its possible applications in cancer therapy. Int J Rad Appl Instrum A. 1986;37:789. doi: 10.1016/0883-2889(86)90273-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vasáros L. Berei K. General properties of astatine. In: Kugler HK, editor; Keller C, editor. Gmelin Handbook of Inorganic Chemistry-Astatine. 8th. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1985. p. 107. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cobb LM. Harrison A. Dudley NE, et al. Relative concentration of astatine-211 and iodine-125 by human fetal thyroid and carcinoma of the thyroid in nude mice. Radiother Oncol. 1988;13:203. doi: 10.1016/0167-8140(88)90057-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garg PK. Harrison CL. Zalutsky MR. Comparative tissue distribution in mice of the alpha-emitter 211At and 131I as labels of a monoclonal antibody and F(ab′)2 fragment. Cancer Res. 1990;50:3514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harrison A. Royle L. Determination of absorbed dose to blood, kidneys, testes and thyroid in mice injected with 211At and comparison of testes mass and sperm number in x-irradiated and 211At treated mice. Health Phys. 1984;46:377. doi: 10.1097/00004032-198402000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larsen RH. Slade S. Zalutsky MR. Blocking [211At]astatide accumulation in normal tissues: Preliminary evaluation of seven potential compounds. Nucl Med Biol. 1998;25:351. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(97)00230-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lundh C. Lindencrona U. Schmitt A, et al. Biodistribution of free 211At and 125I- in nude mice bearing tumors derived from anaplastic thyroid carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2006;21:591. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2006.21.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamilton JG. Aisling CW. Garrison WM, et al. The accumulation, metabolism, and biological effects of astatine in rats and monkeys. Univ Calif Publ Pharmacol. 1953;2:283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindegren S. Back T. Jensen HJ. Dry-distillation of astatine-211 from irradiated bismuth targets: A time-saving procedure with high recovery yields. Appl Radiat Isot. 2001;55:157. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8043(01)00044-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee HB. Blaufox MD. Blood volume in the rat. J Nucl Med. 1985;26:72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Endo S. Nitta Y. Ohtaki M, et al. Estimation of dose absorbed fraction for 131I-beta rays in rat thyroid. J Radiat Res (Tokyo) 1998;39:223. doi: 10.1269/jrr.39.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eckerman KF. Endo A. MIRD: Radionuclide Data and Decay Schemes. 2nd. Reston, VA: Society of Nuclear Medicine; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Spitzweg C. Joba W. Eisenmenger W, et al. Analysis of human sodium iodide symporter gene expression in extrathyroidal tissues and cloning of its complementary deoxyribonucleic acids from salivary gland, mammary gland, and gastric mucosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:1746. doi: 10.1210/jcem.83.5.4839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shellabarger CJ. Godwin JT. Studies on the thyroidal uptake of astatine in the rat. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1954;14:1149. doi: 10.1210/jcem-14-10-1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kleiber M. Body size and metabolic rate. Physiol Rev. 1947;27:511. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1947.27.4.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aronsson EF. Gretarsdottir J. Jacobsson L, et al. Therapy with 125I-labelled internalized and non-internalized monoclonal antibodies in nude mice with human colon carcinoma xenografts. Nucl Med Biol. 1993;20:133. doi: 10.1016/0969-8051(93)90105-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Uusijärvi H. Bernhardt P. Forssell-Aronsson E. Translation of dosimetric results of preclinical radionuclide therapy to clinical situations: Influence of photon irradiation. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2007;22:268. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2006.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Josefsson A. Forssell-Aronsson E. Microdosimetric analysis of 211At in thyroid models for man, rat and mouse. EJNMMI Res. 2012;2:29. doi: 10.1186/2191-219X-2-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]