Abstract

Background

Regional anaesthesia may reduce the risk of persistent (chronic) pain after surgery, a frequent and debilitating condition. We compared regional anaesthesia vs conventional analgesia for the prevention of persistent postoperative pain (PPP).

Methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, PubMed, EMBASE, and CINAHL from their inception to May 2012, limiting the results to randomized, controlled, clinical trials (RCTs), supplemented by a hand search in conference proceedings. We included RCTs comparing regional vs conventional analgesia with a pain outcome at 6 or 12 months. The two authors independently assessed methodological quality and extracted data. We report odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) as our summary statistic based on random-effects models. We grouped studies according to surgical interventions.

Results

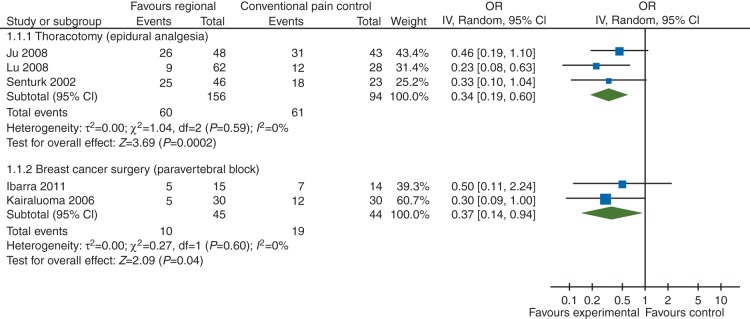

We identified 23 RCTs. We pooled data from 250 participants in three trials after thoracotomy with outcomes at 6 months. Data favoured epidural anaesthesia for the prevention of PPP with an OR of 0.33 (95% CI 0.20–0.56). We pooled two studies investigating paravertebral block for breast cancer surgery; pooled data of 89 participants with outcomes ∼6 months favoured paravertebral block with an OR of 0.37 (95% CI 0.14–0.94). Adverse effects were reported sparsely.

Conclusions

Epidural anaesthesia and paravertebral block, respectively, may prevent PPP after thoracotomy and breast cancer surgery in about one out of every four to five patients treated. Small numbers, performance bias, attrition, and incomplete outcome data especially at 12 months weaken our conclusions.

Keywords: chronic pain, meta-analysis, prevention, regional anaesthesia, systematic review

Editor's key points.

This co-publication of a Cochrane review addresses the role of regional anaesthesia in preventing persistent postoperative pain (PPP).

Randomized controlled trials, which had pain at 6 and 12 months as the outcome measure, were reviewed.

Results show that epidural anaesthesia and paravertebral block may prevent chronic postoperative pain after thoracotomy and breast surgery.

Importantly, one out of every four to five treated patients could benefit.

Chronic pain is a frequent and debilitating condition with inadequate treatment to date.1 Persistent postoperative pain (PPP) is often neglected in spite of its severity and high prevalence, possibly because of limited treatment options.2,3 Mild chronic pain can significantly impact function and quality of life4; severe chronic intractable pain is devastating. Pain persists in every second patient months after thoracotomy, amputation, or breast surgery.3 The sheer volume of interventions makes prevention a major concern even for surgeries with a low risk for persistent pain such as hernia repairs and Caesarean sections.5

Poorly controlled perioperative pain can trigger central sensitization (CS), a stepwise permanent modification of spinal pain pathways involving protein synthesis and permanent modification of synaptic strength.6 CS can lead to hyperalgesia and chronic pain.7,8 Many have studied the optimal timing of regional anaesthesia,8,9 a concept called pre-emptive analgesia.8 In contrast, the preventive analgesia concept hypothesizes that the integration of nociceptive impulses over time leads to PPP, because CS is a comprehensive stepwise process.8,10 Hence, blocking nociception during any part of the perioperative experience may prevent persistent pain after surgery,8 but randomized controlled trials (RCTs) report conflicting results.8,11–16 Narrative reviews on regional anaesthesia for PPP raised awareness, but no systematic review or formal evidence synthesis has been attempted to date.3,8,17

Objective

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis for the Cochrane Collaboration to compare regional anaesthesia to conventional analgesia for the prevention of persistent pain 6–12 months after surgery.18

Methods

Search, selection, and inclusion criteria

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, PubMed, EMBASE, and CINAHL from their inception to May 2012 without any language restriction. We used a combination of free-text search and controlled vocabulary search. We limited results to RCTs using a highly sensitive search strategy.19 We conducted a hand search in reference lists of included trials, review articles, and conference abstracts. We detailed our methods a priori in a published protocol20 and published the search strategies elsewhere in detail.18

Types of studies

We included RCTs. The effects of nerve blocks are obvious to patients and providers; therefore, we accepted single blinding. Blinding of the outcome observer was a prerequisite for inclusion.

Types of participants: we included studies in adults and children undergoing elective surgical procedures. We excluded trauma surgery.

Types of interventions: we included studies comparing local anaesthetics or regional anaesthesia vs conventional pain control. We included all routes of administration of local anaesthetics. We included studies providing regional anaesthesia during any time window in the perioperative period. We excluded studies comparing one regional technique vs another or investigating the effect of timing.

Types of comparators: we included studies which used conventional postoperative pain control such as opioids with or without concomitant nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or adjuvants.

Types of outcomes: we studied dichotomous pain outcomes as reported in the studies (pain vs no pain; pain or use of pain medication, or both, vs no pain). We included studies assessing differences in scores based on validated pain scales.

Summary statistic

We chose the odds ratio (OR) as the summary statistic for our dichotomous primary outcome. We reported the ORs with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We calculated the number needed (NNT) to treat for the subgroups of thoracotomy and breast cancer surgery.21

Data extraction

The two authors independently assessed the methodological quality and extracted data in duplicate including on adverse effects using a standard data collection form, revised after a pilot run.18 The two authors checked and entered the data into the Cochrane Review Manager (RevMan 5.1, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, København, Denmark) computer software.22 We published a detailed table of characteristics of included studies listing trials design, participants, interventions, and reported outcomes elsewhere.18 We contacted the study authors about the missing data and reported data inconsistencies in the aforementioned table of included studies.18

Assessment of risk of bias

The two authors independently graded the quality of studies based on a checklist of design components. The main categories consisted of randomization, allocation concealment, observer blinding, and dealing with the missing data and are classified as high, low, or unclear risk of bias. We achieved consensus by informal discussion.23

Stratification and assessment of heterogeneity and reporting bias

We grouped studies according to surgical interventions (thoracotomy, limb amputation, breast cancer surgery, laparotomy, and other) instead of pooling across different surgical interventions: each surgical intervention has a different natural history of chronic pain.3 We investigated study heterogeneity at the subgroup level using a χ2 test and the calculation of the I2 statistic.24 We considered an examination of publication bias using graphical and statistical tests (funnel plot, Egger's test).25

We combined all groups using regional or local anaesthesia together and compared them against the groups using conventional pain control, if in a study several groups used variable timing of their regional anaesthesia interventions in different arms. For example, if the first study group received a regional anaesthesia intervention before incision and the second study group received it after incision, we pooled the (first and second) groups using local anaesthetics against the (third) control groups not using any local anaesthetics at all (i.e. using only conventional pain control instead).

If the follow-up varied only by weeks to 1 month, we pooled the results, for example data at 24 weeks or at 5 months with data at 6 months.

Data synthesis

We used the inverse-variance approach, adjusting study weights based on the extent of variation among the varying intervention effects.23 A random-effects model will result in wider CIs for the average intervention effect as it accounts for any potential between-study variance. The result is a more conservative effect estimate.26 We provide the summary of findings in tables, after the process of GRADE27 assessment, elsewhere.18

Results

Search

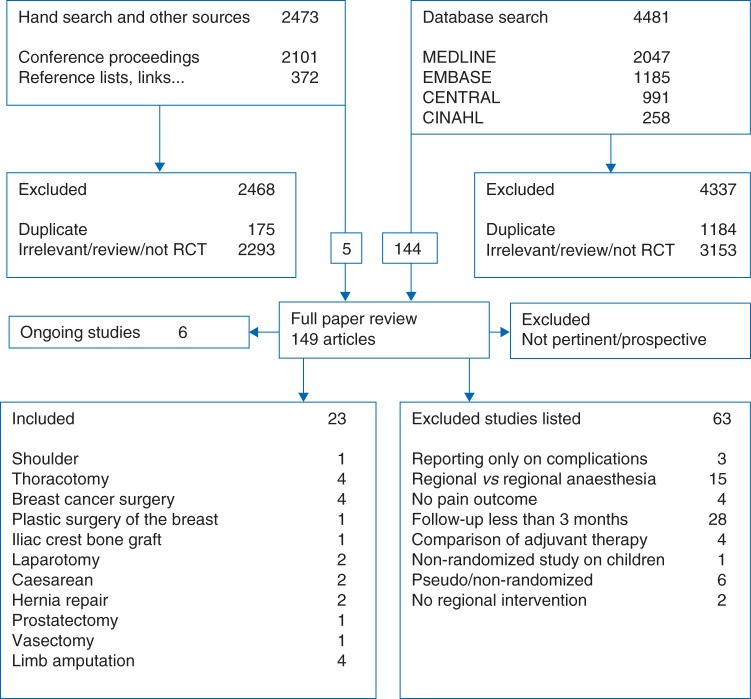

We give an overview of our search in Figure 1. Electronic searches were performed in February and March 2008, and updated between February and August 2010 and again between April and May 2012. Our electronic search retrieved 4481 references, 2047 in MEDLINE, 1185 in EMBASE, 991 in CENTRAL, 258 in CINAHL; we identified 1184 duplicates among them and excluded 4337 references as irrelevant or not RCTs in the screening process.

Fig 1.

Search diagram. The search diagram gives an overview of the search and selection process.

We performed a hand search and checked 2101 abstracts in the conference proceedings of the International Anesthesia Research Society and the European Society of Regional Anaesthesia for 2005–2007. Including links or references to relevant related articles, we found 372 references. Of a total of 2473 references, we excluded 2293 (+175 to be deemed duplicates) as irrelevant or not RCTs (Fig. 1). We included and reviewed manuscripts in several languages other than English, including Danish,28 Mandarin,12 Japanese,29 German,30 French,31,32 and Spanish.33 Three of the five studies included in our data synthesis were published in the non-English literature and hence were less accessible to most clinicians.11,33,34

Among 144 full-text articles, we identified 23 studies for inclusion (Fig. 1). We identified six on-going trials listed in detail in the full review.18

Included studies

We identified 23 RCTs studying regional anaesthesia or local anaesthetics for the prevention of chronic pain after surgery.11,13,31–48 We present an abbreviated table of included studies (Table 1) and reported details of the search, selection and on the methodological quality and other characteristics of the included studies elsewhere.18 We found five large on-going trials on regional anaesthesia for the prevention of chronic pain after surgery, plus one trial likely to report on PPP as a secondary outcome listed in the full review.18 We found many studies reporting outcomes only at 3 months or 12 weeks and will include these in the next review update possibly using a Bayesian approach to prevent the unit of analysis issues in pooling trials with repeated measures and data collected at disparate follow-ups.49,50

Table 1.

Table of included studies grouped according to surgical intervention. Complete details on participants, the regional anaesthesia intervention, the conventional control group and adjuvants, the timing, the follow-up, and reported outcomes are published elsewhere18

| Study ID | Regional technique | Timing of intervention | Adjuvants | Outcomes |

Follow-up | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binary | Continuous | |||||

| Plastic surgery of the breast | ||||||

| Bell and colleagues, 200136 | Local infiltration | Single-shot, pre-incision vs control | None | Pain/no pain | Allodynia/hyperalgesia | 6 months |

| Breast cancer surgery | ||||||

| Baudry and colleagues, 200831 | Local infiltration | Single-shot, pre-incision vs control | None | Pain/no pain | McGill results not reported | 18 months |

| Ibarra and colleagues, 201133 | Single shot, paravertebral block | Single shot, pre-incision vs control | None | Phantom; neuropathic pain | 3 and 5 months | |

| Kairaluoma and colleagues, 200613 | Single shot, paravertebral block | Single shot, pre-incision vs control | None | Numerical Rating Scale>3 | Analgesic consumption | 12 months |

| Fassoulaki and colleagues, 200538 | Topical application | Post-incision, continuous postoperative vs control | Gabapentin | Pain/no pain | Analgesic consumption | 6 months |

| Caesarean section | ||||||

| Lavand'homme and colleagues, 200745 | Wound irrigation | Pre-incision, continuous postoperative vs control | None | Pain/no pain | Analgesic consumption | 6 months |

| Shahin and colleagues, 201055 | Peritoneal instillation | Post-incision, single shot vs placebo | None | Pain/no pain | Numerical Rating Scale | 8 months |

| Iliac crest bone graft harvesting | ||||||

| Singh and colleagues, 200753 | Wound irrigation | Post-incision, continuous postoperative vs control | None | Pain/no pain | VAS, pain frequency, functional activity score, overall satisfaction | 4.7 yr |

| Hernia repair | ||||||

| Burney and colleagues, 200437 | Spinal | Single shot, pre-incision vs control | None | ? | Short Form (36) Health Survey | 6 months |

| Mounir and colleagues 201032 | Wound infiltration | Single shot post-incision vs placebo | None | Pain/no pain | None | 6 months |

| Laparotomy | ||||||

| Lavand'homme and colleagues, 200544 | Epidural | Pre-incision, continuous postoperative vs control | Ketamine, Clonidine | Pain/no pain | Mental Health Inventory | 12 months |

| Katz and colleagues, 200414 | Epidural | Single shot, pre- vs postoperative vs none | None | Pain/no pain | Pain Disability Index and Mental Health Inventory | 6 months |

| Amputation | ||||||

| Karanikolas and colleagues, 201140 | Epidural | Pre- vs intra- vs postoperative vs all vs none | None | Pain/no pain | VAS, phantom pain frequency, McGill | 6 months |

| Katsuly-Liapis and colleagues, 199641 | Epidural | Pre- vs postoperative vs none | None | Pain/no pain | 12 months | |

| Pinzur and colleagues, 199647 | Nerve sheath irrigation | Intra- and continuous postoperative vs none | None | Pain/no pain | McGill | 6 months |

| Reuben and colleagues, 200648 | Nerve sheath irrigation | Single shot, post-incision vs control | Clonidine | Phantom pain, stump pain | 12 months | |

| Prostatectomy | ||||||

| Haythornthwaite and colleagues, 199839 | Epidural | Pre-incision vs postoperative | None | Pain/no pain | Allodynia/hyperalgesia | 6 months |

| Shoulder surgery | ||||||

| Bain and colleagues, 200135 | Brachial plexus block | Single shot, pre-incision vs control | None | VAS, mean analgesic dosages, orthopaedic functional score | 12 months | |

| Thoracatomy | ||||||

| Ju and colleagues, 200811 | Epidural | Pre-incision and postoperative vs control | None | Pain/no pain | Allodynia | 12 months |

| Senturk and colleagues, 200216 | Epidural | Pre-incision vs postoperative vs control | None | Pain/no pain | Numerical Rating Scale, pain affecting daily living | 6 months |

| Lu and colleagues, 200834 | Epidural | Pre-incision vs postoperative vs control | None | Pain/no pain | 6 months | |

| Katz and colleagues, 199642 | Intercostal nerve blocks | Single shot, post-incision vs control | None | Pain/no pain | VRS, analgesic consumption | 18 months |

| Vasectomy | ||||||

| Paxton and colleagues, 199546 | Local injection VAS deferens | Single shot, post-incision vs control | None | Discomfort/no discomfort | 12 months | |

Excluded studies

We excluded no study for the lack of observer blinding alone. We considered the randomization inadequate in three trials.28,51,52 One51 of them would have also been excluded for failing on additional inclusion criteria.

Missing and duplicate data

We estimated that separate articles by the same author with identical participant numbers were reporting in fact on just one single trial and used these data sets only once.13,14,39,42,53 Despite our best efforts to reach the authors, we were not able to secure suitable or appropriate data for some studies.35,37,39,47

Regional techniques and surgical interventions

Studies were clustered in broad categories (thoracotomy, limb amputation, breast surgery, laparotomy, and other). For thoracotomy the only regional technique studied was epidural anaesthesia.11,12,16 Two studies on breast cancer surgery used paravertebral blocks.13,33 In most other surgical subgroups, regional anaesthesia techniques varied (Table 1).

We pooled the data of 250 participants after thoracotomy and that of 89 women after breast cancer surgery with outcomes at 6 months. Only adults (>18 yr) were studied. Known risk factors for the development of persistent (chronic) pain were not reported, potentially introducing bias.54

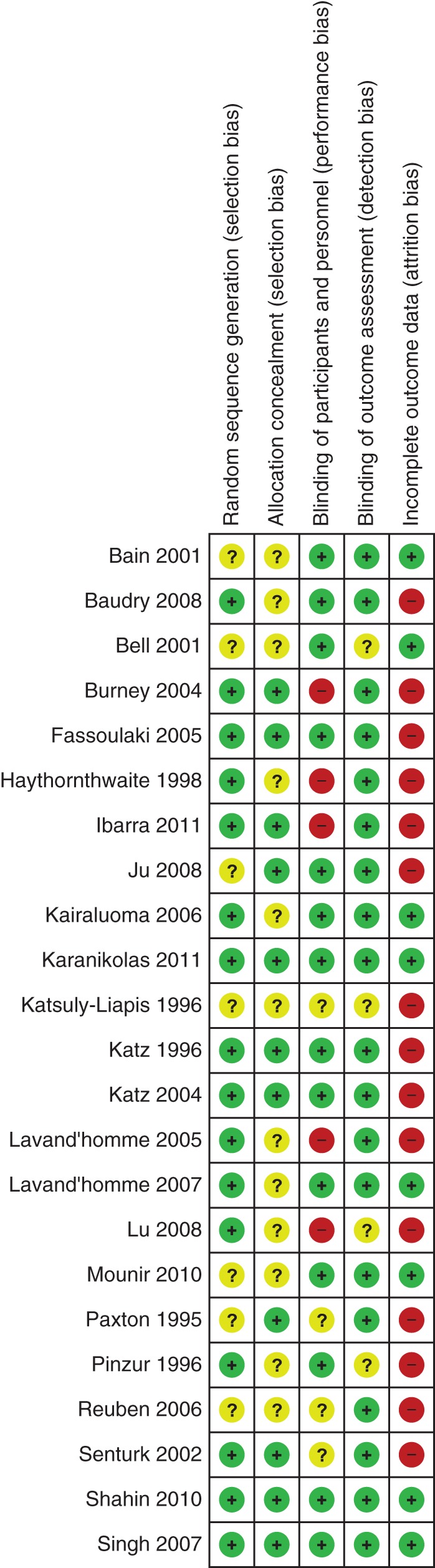

Methodological quality

We summarized the risk of bias of included studies in Figure 2. We published a detailed table of risk of bias with justifications for our classifications elsewhere.18

Randomization: Six studies did not detail the process of sequence generation.11,13,35,36,39,41 Study authors’ responses provided additional unpublished information for some studies.16,33,39,45 Three studies were excluded for pseudo-randomization.28,51,52

Allocation concealment: only eight studies described adequate concealment of allocation.13,14,16,37,38,40,42,46

Blinding: effective blinding of patients and practitioners is difficult because many patients note the sensory effects of regional anaesthesia. Many authors made great efforts to blind participants, providers, and outcome assessors. No study was excluded for detection bias, and only outcome assessment blinding was a prerequisite for inclusion.

Incomplete outcome data: with the exception of six mostly recent studies,13,32,35,40,53,55 most studies did not adequately address incomplete outcome data.

Selective reporting: adverse outcomes were reported only anecdotally if at all in the included studies, raising concerns about selective reporting of unintended effects.

Fig 2.

Risk of bias graph. The review authors summarize their judgements about each study for each risk of bias category in the methodological summary figure. Detailed justifications are published elsewhere.18

Effect of the intervention

Thoracotomy

Our data synthesis (Fig. 1: forest plot) of 250 participants in three studies11,12,16 strongly favoured epidural anaesthesia for thoracotomy with an OR of 0.34 (95% CI 0.19–0.60) (P=0.0002). Excluding one study11 using cryotherapy as the control group did not alter the results. We found no evidence of between-study heterogeneity (I2 estimate of 0%).

Breast surgery

Our analysis equally favoured paravertebral blocks for breast cancer surgery with an OR of 0.37 (95% CI 0.14–0.94) (P=0.04) based on two studies13,33 with 89 participants, when we excluded plastic surgery of the breast36 and a study with multimodal topical analgesia.38 Evidence synthesis including also these studies increased the confidence in the effect measure with an OR of 0.42 (95% CI 0.21–0.86) (P=0.02).

For the remaining subgroups and for the later follow-up intervals, the data were too sparse for evidence synthesis.18

Limb amputation

We did not pool two studies40,41 with 67 patients investigating the effect of regional anaesthesia after limb amputation on chronic pain (phantom limb pain) at 6 months. The small number of subjects and the high variance would have resulted in a very large CI; considerable heterogeneity was also suggested by an I2 estimate of 78%. The interpretation might have been controversial considering the exclusion of two studies in this subgroup for pseudo-randomization.28,52

Laparotomy

We did not pool data from two studies with data at 6 months on 189 laparotomy patients as an I2 estimate of 90% suggested marked study heterogeneity. The positive study44 used adjuvants and comprehensive postoperative nociceptive block, while the inconclusive study14 used neither adjuvants nor any regional anaesthesia after operation. At 12 months, a single study44 favoured regional anaesthesia with an OR of 0.08 [95% CI 0.01–0.45].

Caesarean section

We found two studies45,55 after Caesarean section (Pfannenstiel incision) including 414 participants, but abstained from pooling the data. One45 used continuous postoperative wound irrigation, the other55 used a single-shot instillation of local anaesthetic into the peritoneal pelvis. Orthodox evidence synthesis would be controversial in the light of this clinical heterogeneity of regional anaesthesia interventions.

Other surgery

We found three single studies;32,46,53 all favoured regional anaesthesia. The OR was 0.01 [95% CI 0.00–0.09] for wound infiltration after iliac hernia repair.32 Continuous local infiltration reduced the risk of PPP after iliac crest bone graft harvesting with an OR of 0.22 [95% CI 0.03–1.42].53 For single-shot local bupivacaine after vasectomy,46 the OR was 0.02 [95% CI 0.00–0.33].

Discussion

Clinical heterogeneity among the included RCTs prevented pooling and meta-analysis of outcomes for many surgical subgroups. Outcomes from a total of 250 patients from three RCTs indicated that epidural anaesthesia reduces the risk of PPP 6 months after open thoracotomy (OR 0.34, NNT 4) (Fig. 3: forest plot) compared with conventional pain control. The effect measures of the three trials were remarkably close and consistent, considering that they were performed in different countries (I2=0%). At 12 months, one single study11 reported this outcome in this subgroup and found no evidence of statistically significant effect (OR 0.56).

Fig 3.

Forest plot: outcomes at 6 months favoured epidural anaesthesia for the prevention of PPP after thoracotomy with an OR of 0.33 (95% CI 0.20–0.56) and paravertebral block for breast cancer surgery with an OR of 0.37 (95% CI 0.14–0.94), respectively. More forest plots are published elsewhere.18

Pooled data from two RCTs on 89 participants suggested that women who received a paravertebral block were less likely to experience PPP after breast cancer surgery than their counterparts who received conventional postoperative pain control (OR 0.37, NNT 5) (Fig. 3: forest plot). Again the results were similar in the two studies completed in different countries (I2=0%). The results did not change when we included data from participants who underwent plastic surgery or received a multimodal regional anaesthesia; the effect measures still showed no heterogeneity. We did not pool the two studies13,31 reporting results 12 months after breast cancer surgery, because we deemed the used regional anaesthesia techniques too different for data synthesis.

Outcomes reported 6 and 12 months after other surgical interventions were clinically too heterogeneous to allow pooling, although these data consistently favoured regional anaesthesia.

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis investigating the effect of regional anaesthesia for the prevention of chronic pain after surgery. We are unaware of any evidence synthesis that demonstrated long-term benefits of regional anaesthesia several months after surgery. Our encouraging results are in contrast to rather guarded conclusions regarding the effect of regional anaesthesia for the prevention of PPP in previous narrative reviews;2,3,8,17 three of the five studies included in our data synthesis were not yet available or not referenced by the above, possibly explaining this discrepancy.11,12,33

Limitations

Participants

It is unclear whether our evidence synthesis on the effects of regional anaesthesia for the prevention of PPP can be translated to other patient populations or other surgical interventions. Data on paravertebral blocks for breast cancer surgery do not predict the effectiveness of this block for post-thoracotomy pain, for example. Regrettably, the effect of regional anaesthesia for the prevention of PPP has not been studied in children to date.56 Immediate postoperative pain control is likely an important predictor and a potential confounder or mediator for the development of PPP. (It is at least a risk factor associated with PPP.)57 Most studies failed to control for this or other risk factors of PPP. Defined at the patient and not at the study level, incorporating these aspects into the analysis would have required an individual patient data meta-analysis or meta-regression.49

Interventions

Different regional anaesthesia techniques may have different effects. We took a cautious approach and synthesized the data in a priori defined surgical subgroups.20 Within each subgroup, investigators used mostly identical regional anaesthesia techniques and the results were rather homogenous. Of course, this lack of evidence for statistical heterogeneity within the predefined subgroups does not prove that the interventions or populations were homogenous. We hope that our conservative approach will convince sceptics as well that pooling was justified.

Comparator

We compared regional anaesthesia with conventional pain control. Local anaesthetics might be effective in preventing PPP also if administered systemically via i.v. route.44,58,59 As only one study had such a comparator group, we have insufficient data to comment on this hypothesis.44 A few studies used adjuvants only in the intervention group. If adjuvants were synergistic, this might have biased the results, but this concern was not germane in the breast cancer and thoracotomy, the only subgroups where we pooled the data. Data were too sparse for meaningful subgroup analysis of the effects of adjuvants or the benefits of continuous vs single-shot nociceptive block.

Outcomes

On one hand, we would have preferred to differentiate between mild, moderate, and severe pain2 and to synthesize more comprehensive instruments for the assessment of chronic pain to capture all the dimensions of chronic pain.60 On the other hand, pain or no pain is an easily comprehensible dichotomy for providers and patients. (Only) binary outcomes were reported in most studies and the data synthesis of continuous with dichotomous outcomes would have been challenging with classical statistical methods,49,61 especially as they often measure different aspects of the human pain experience.60 Mild chronic pain can severely interfere with daily life.3,4 Hence, its prevention is warranted especially in young healthy individuals after minor elective procedure like vasectomy,46 Caesarean section,45 or iliac crest bone graft harvesting.53 Analogous to responder analysis, promoted for the analysis of chronic pain trials,62 a binary outcome is a reasonable choice to investigate the prevention of PPP by regional anaesthesia.63

Inconsistent and anecdotal reporting of adverse effects precluded a data synthesis of the risks of regional anaesthesia. Registries and large observational studies seem better suited to investigate the (rather rare) permanent neurological damage after regional anaesthesia.64,65

Study design

The included studies were mostly of intermediate methodological quality. Our methodological summary overview details the important limitations for each study in each risk of bias category, as judged by the authors (Fig. 2). Participant blinding was difficult considering the nature of regional anaesthesia. Clearly, performance bias may weaken the conclusions we drew in our review, considering that the placebo effect seems especially important for pain outcomes. Flaws in allocation concealment weaken our conclusions considerably.66 Attrition and incomplete outcome data equally dampen our confidence in the results.67 Our conclusions are weakened by the small number of included studies and patients.68

Review process and statistical model

Studies reported their primary outcomes, arguing against reporting bias, except for adverse effects which were consistently underreported. Our inability to obtain and include all outcome data might have led to publication bias.18 The small number of included studies prevented us from attempting a formal analysis: a funnel plot or the test proposed by Egger is meaningful only when >10 studies are displayed.25 A sensitivity analysis suggested that our model and statistical assumptions did not influence the results.67

Future studies

The effects of regional anaesthesia on PPP in children should be investigated by RCTs. We ought to study the synergistic effect adjuvant medications might afford in the prevention of PPP. Besides comparing the regional anaesthesia with a conventional pain control, studies could consider to include an i.v. local anaesthetic control group to confirm or refute the hypothesis that i.v. local anaesthetics are equally effective, while much easier to administer.44,58,59 Studies should report dichotomous pain outcomes, elicit analgesic consumption, and use comprehensive pain assessment instruments.60 The assessment of baseline pain before surgery is imperative, in particular, for limb amputation.28 Risk factors should be elicited and reported separately for each group.2

Conclusions

We recommend epidural anaesthesia for patients undergoing open thoracotomy and paravertebral blocks for women undergoing breast cancer surgery for risk reduction of PPP 6 months after surgery. Chronic pain after surgery, devastating and difficult to treat, could be prevented in one patient out of every four to five patients treated. Different studies conducted in various institutions on different continents were remarkably homogenous and consistent in their estimates of the effect measure (I2=0%) and our findings are robust to sensitivity analysis and model assumptions. We caution that these conclusions cannot be extrapolated to other surgical interventions or regional anaesthesia techniques. Small numbers, performance bias, attrition, and incomplete outcome data especially at 12 months weaken our conclusions significantly.68 Our results showcase a pervasive pattern of PPP in most of the surgical specialties and suggest that regional anaesthesia can potentially reduce this risk after many different surgical interventions.

Authors’ contributions

M.H.A. was responsible for conceiving and coordinating the review. M.H.A. performed preliminary work that was the foundation of this review. M.H.A. organized retrieval of the papers and contacted authors for additional information. D.A.A. and M.H.A. together performed the search, selection, data extraction, and appraisal of the methodological quality of included studies. M.H.A. and D.A.A. together entered the data, interpreted the data and drew conclusions. M.H.A. performed the statistical analysis, built the tables, conceived the figures, wrote the review, and is the guarantor. Both M.H.A. and D.A.A. read the review and checked it before submission.

Declaration of interest

None declared.

Funding

National Institutes of Health (NIH), USA: the project described was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), through CTSA grant numbers UL1TR000086, TL1RR000087, and KL2TR000088. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Acknowledgements

This is a co-publication of our published Cochrane review for the Cochrane Anaesthesia Group to reach a larger clinical audience. We thank Dr A. Timmer for her guidance, support and advice, and encouragement in conceiving, developing, executing, interpreting, and writing the protocol and review. We thank Associate Professor Michael Bennet (content editor), Professor Nathan Pace (statistical editor), Dr Ewan McNicol, and Dr Patricia Lavand'homme (peer reviewers), and Durhane Wong-Rieger (consumer reviewer) for their help and editorial advice during the preparation of this systematic review. We thank Dr Jane Ballantyne (content editor), Dr W. Scott Beattie, and Professor Martin Tramèr (peer reviewers), and Janet Wale (consumer) for their help and editorial advice during the preparation of the protocol for this systematic review. We thank Dr Hung-Mo Lin for her help in extracting methodological information from the article in Chinese (Lu and colleagues).34

References

- 1.Finnerup NB, Sindrup SH, Jensen TS. The evidence for pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain. Pain. 2010;150:573–81. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kehlet H, Jensen TS, Woolf CJ. Persistent postsurgical pain: risk factors and prevention. Lancet. 2006;367:1618–25. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68700-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macrae WA. Chronic post-surgical pain: 10 years on. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101:77–86. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gottschalk A, Cohen SP, Yang S, Ochroch EA. Preventing and treating pain after thoracic surgery. Anesthesiology. 2006;104:594–600. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200603000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sng BL, Sia AT, Quek K, Woo D, Lim Y. Incidence and risk factors for chronic pain after caesarean section under spinal anaesthesia. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2009;37:748–52. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0903700513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sandkuhler J, Gruber-Schoffnegger D. Hyperalgesia by synaptic long-term potentiation (LTP): an update. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2012;12:18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2011.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woolf CJ, Salter MW. Neuronal plasticity: increasing the gain in pain. Science. 2000;288:1765–9. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5472.1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katz J, Clarke H, Seltzer Z. Review article: preventive analgesia: quo vadimus? Anesth Analg. 2011;113:1242–53. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31822c9a59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ong CK, Lirk P, Seymour RA, Jenkins BJ. The efficacy of preemptive analgesia for acute postoperative pain management: a meta-analysis. Anesth Analg. 2005;100:757–73. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000144428.98767.0E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Woolf CJ, Chong MS. Preemptive analgesia: treating postoperative pain by preventing the establishment of central sensitisation. Anesth Analg. 1993;77:362–79. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199377020-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ju H, Feng Y, Yang BX, Wang J. Comparison of epidural analgesia and intercostal nerve cryoanalgesia for post-thoracotomy pain control. Eur J Pain. 2008;12:378–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu YL, Wang XD, Lai RC. [Correlation of acute pain treatment to occurrence of chronic pain in tumor patients after thoracotomy] Ai Zheng. 2008;27:206–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kairaluoma PM, Bachmann MS, Rosenberg PH, Pere PJ. Preincisional paravertebral block reduces the prevalence of chronic pain after breast surgery. Anesth Analg. 2006;103:703–8. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000230603.92574.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katz J, Cohen L. Preventive analgesia is associated with reduced pain disability 3 weeks but not 6 months after major gynecologic surgery by laparotomy. Anesthesiology. 2004;101:169–74. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200407000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ochroch EA, Gottschalk A, Augostides J, et al. Long term pain and activity during recovery from major thoracotomy using thoracic epidural anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:1234–44. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200211000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Senturk M, Ozcan PE, Talu GK, et al. The effects of three different analgesia techniques on long-term postthoracotomy pain. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:11–5. doi: 10.1213/00000539-200201000-00003. table of contents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacRae WA. Chronic pain after surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:88–98. doi: 10.1093/bja/87.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andreae MH, Andreae DA. Local anaesthetics and regional anaesthesia for preventing chronic pain after surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD007105. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007105.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 4.2.6 [updated September 2006] The Cochrane Collaboration; 2006. available from www.cochrane-handbook.org. (accessed 6 October 2006) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andreae MH, Andreae DA, Motschall E, Rücker G, Timmer A. Local anaesthetics and regional anaesthesia for preventing chronic pain after surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008:CD007105. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007105.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cook RJ, Sackett DL. The number needed to treat: a clinically useful measure of treatment effect. Br Med J (Clinical Research Ed) 1995;310:452–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6977.452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.1 for Windows. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 5.1.0 [updated March 2011] The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. Available from www.cochrane-handbook.org. (accessed 24 May 2013) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–58. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Br Med J (Clinical Research Ed) 1997;315:629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grade Working Group. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Br Med J. 2004;328:1490–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bach S, Noreng MF, Tjellden NU. Phantom limb pain in amputees during the first 12 months following limb amputation, after preoperative lumbar epidural blockade. Pain. 1988;33:297–301. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(88)90288-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hirakawa N, Fukui M, Takasaki M, Harano K, Totoki T. The effect of preemptive analgesia on the persistent pain following thoracotomy. Anesth Resusc [Masui to Sosei] 1996;32:263–6. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weihrauch JO, Jehmlich M, Leischik M, Hopf HB. Are peripheral nerve blocks of the leg (femoralis in combination with anterior sciatic blockade) as sole anaesthetic technique an alternative to epidural anaesthesia. Anasthesiol Intensivmed Notfallmed Schmerzther. 2005;40:18–24. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-826200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baudry G, Steghens A, Laplaza D, et al. [Ropivacaine infiltration during breast cancer surgery: postoperative acute and chronic pain effect] Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2008;27:979–86. doi: 10.1016/j.annfar.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mounir K, Bensghir M, Elmoqaddem A, et al. [Efficiency of bupivacaine wound subfasciale infiltration in reduction of postoperative pain after inguinal hernia surgery] Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2010;29:274–8. doi: 10.1016/j.annfar.2009.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ibarra MM, GC SC, Vicente GU, Cuartero del Pozo A, Lopez Rincon R, Fajardo del Castillo MJ. Chronic postoperative pain after general anesthesia with or without a single-dose preincisional paravertebral nerve block in radical breast cancer surgery. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim. 2011;58:290–4. doi: 10.1016/s0034-9356(11)70064-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu YL, Wang XD, Lai RC, Huang W, Xu M. Correlation of acute pain treatment to occurrence of chronic pain in tumor patients after thoracotomy. Aizheng. 2008;27:206–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bain GI, Rudkin G, Comley AS, Heptinstall RJ, Chittleborough M. Digitally assisted acromioplasty: the effect of interscalene block on this new surgical technique. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:44–9. doi: 10.1053/jars.2001.19665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bell RF, Sivertsen A, Mowinkel P, Vindenes H. A bilateral clinical model for the study of acute and chronic pain after breast-reduction surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2001;45:576–82. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2001.045005576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burney RE, Prabhu MA, Greenfield ML, Shanks A, O'Reilly M. Comparison of spinal vs general anesthesia via laryngeal mask airway in inguinal hernia repair. Arch Surg. 2004;139:183–7. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fassoulaki A, Triga A, Melemeni A, Sarantopoulos C. Multimodal analgesia with gabapentin and local anesthetics prevents acute and chronic pain after breast surgery for cancer. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:1427–32. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000180200.11626.8E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haythornthwaite JA, Raja SN, Fisher B, Frank SM, Brendler CB, Shir Y. Pain and quality of life following radical retropubic prostatectomy. J Urol. 1998;160:1761–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karanikolas M, Aretha D, Tsolakis I, et al. Optimized perioperative analgesia reduces chronic phantom limb pain intensity, prevalence, and frequency: a prospective, randomized, clinical trial. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:1144–54. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31820fc7d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Katsuly-Liapis I, Georgakis P, Tierry C. Preemptive extradural analgesia reduces the incidence of phantom pain in lower limb amputees. Br J Anaesth. 1996;76(125 Suppl. 2) (abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 42.Katz J, Jackson M, Kavanagh BP, Sandler AN. Acute pain after thoracic surgery predicts long-term post-thoracotomy pain. Clin J Pain. 1996;12:50–5. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199603000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Katz J, Cohen L, Schmid R, Chan VW, Wowk A. Postoperative morphine use and hyperalgesia are reduced by preoperative but not intraoperative epidural analgesia: implications for preemptive analgesia and the prevention of central sensitization. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:1449–60. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200306000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lavand'homme P, De Kock M, Waterloos H. Intraoperative epidural analgesia combined with ketamine provides effective preventive analgesia in patients undergoing major digestive surgery. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:813–20. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200510000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lavand'homme PM, Roelants F, Waterloos H, De Kock MF. Postoperative analgesic effects of continuous wound infiltration with diclofenac after elective cesarean delivery. Anesthesiology. 2007;106:1220–5. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000267606.17387.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paxton LD, Huss BK, Loughlin V, Mirakhur RK. Intra-vas deferens bupivacaine for prevention of acute pain and chronic discomfort after vasectomy. Br J Anaesth. 1995;74:612–3. doi: 10.1093/bja/74.5.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pinzur MS, Garla PG, Pluth T, Vrbos L. Continuous postoperative infusion of a regional anesthetic after an amputation of the lower extremity. A randomized clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:1501–5. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199610000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reuben SS, Raghunathan K, Roissing S. Evaluating the analgesic effect of the perioperative perineural infiltration of bupivacaine and clonidine at the site of injury following lower extremity amputation. Acute Pain. 2006;8:117–23. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG. Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hall CB. Estimation of bivariate measurements having different change points, with application to cognitive ageing. Stat Med. 2001;20:3695–714. doi: 10.1002/sim.1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.da Costa VV, de Oliveira SB, Fernandes Mdo C, Saraiva RA. Incidence of regional pain syndrome after carpal tunnel release. Is there a correlation with the anesthetic technique? Rev Bras Anestesiol. 2011;61:425–33. doi: 10.1016/S0034-7094(11)70050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nikolajsen L, Ilkjaer S, Christensen JH, Kroner K, Jensen TS. Randomised trial of epidural bupivacaine and morphine in prevention of stump and phantom pain in lower-limb amputation. Lancet. 1997;350:1353–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)06315-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Singh K, Phillips FM, Kuo E, Campbell M. A prospective, randomized, double-blind study of the efficacy of postoperative continuous local anesthetic infusion at the iliac crest bone graft site after posterior spinal arthrodesis: a minimum of 4-year follow-up. Spine. 2007;32:2790–6. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31815b7650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fassoulaki A, Melemeni A, Staikou C, Triga A, Sarantopoulos C. Acute postoperative pain predicts chronic pain and long-term analgesic requirements after breast surgery for cancer. Acta Anaesthesiol Belg. 2008;59:241–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shahin AY, Osman AM. Intraperitoneal lidocaine instillation and postcesarean pain after parietal peritoneal closure: a randomized double blind placebo-controlled trial. Clin J Pain. 2010;26:121–7. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181b99ddd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ilfeld BM, Smith DW, Enneking FK. Continuous regional analgesia following ambulatory pediatric orthopedic surgery. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2004;33:405–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Perkins FM, Kehlet H. Chronic pain after surgery: a review of predictive factors. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:1123–33. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200010000-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Strichartz GR. Novel ideas of local anaesthetic actions on various ion channels to ameliorate postoperative pain. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101:45–7. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vigneault L, Turgeon AF, Cote D, et al. Perioperative intravenous lidocaine infusion for postoperative pain control: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Can J Anaesth. 2011;58:22–37. doi: 10.1007/s12630-010-9407-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Turk DC, Dworkin RH, Burke LB, et al. Developing patient-reported outcome measures for pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2006;125:208–15. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chinn S. A simple method for converting an odds ratio to effect size for use in meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2000;19:3127–31. doi: 10.1002/1097-0258(20001130)19:22<3127::aid-sim784>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, McDermott MP, et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of group differences in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2009;146:238–44. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moore RA, Moore OA, Derry S, Peloso PM, Gammaitoni AR, Wang H. Responder analysis for pain relief and numbers needed to treat in a meta-analysis of etoricoxib osteoarthritis trials: bridging a gap between clinical trials and clinical practice. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:374–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.107805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brull R, McCartney CJ, Chan VW, El-Beheiry H. Neurological complications after regional anesthesia: contemporary estimates of risk. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:965–74. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000258740.17193.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schnabel A, Reichl SU, Kranke P, Pogatzki-Zahn EM, Zahn PK. Efficacy and safety of paravertebral blocks in breast surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Br J Anaesth. 2010;105:842–52. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hewitt C, Hahn S, Torgerson DJ, Watson J, Bland JM. Adequacy and reporting of allocation concealment: review of recent trials published in four general medical journals. Br Med J. 2005;330:1057–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38413.576713.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Introduction to Meta-analysis. Chichester: Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pereira TV, Ioannidis JP. Statistically significant meta-analyses of clinical trials have modest credibility and inflated effects. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:1060–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]