Abstract

Responding effectively and efficiently to the needs of persons with mental illness returning to the community from prison requires identifying their differences in need and placement difficulties upon return and targeting reintegration investments to reflect these differences. This paper has three parts. The first part profiles the male special needs population in New Jersey prisons. These profiles describe behavioral health and criminal justice characteristics of 2715 male inmates with mental health problems, and are used to identify the scope and nature of the public’s investment opportunity. The next part describes the costs associated with possible "investments." The special needs population is classified by need and placement difficulty, and then matched to reentry and community-based treatment programs. Costs are estimated for reentry planning and community-based treatment for the first year post-release. The third part recommends an investment strategy and a set of operational changes that might minimize the loss and maximize the return on the public s investment dollar in mental health.

Keywords: Community, Prisoners, Mental illness

1. Introduction

In an average year in the United States, approximately 96,000 prison inmates will reenter the community with acute to severe mental health problems. The vast majority of these inmates received treatment for their mental health problems while incarcerated, and a significant part of that treatment included taking psychotropic medications (Beck & Maruschak, 2001; Ditton, 1999; Human Rights Watch, 2003). For inmates with mental health problems reentering the community from prison, treatment is critical. Treatment is the most effective and efficient method for assuring the best set of health and justice outcomes for the individual and society. There is ample research evidence that underscores the need for continuity of treatment for persons with mental health problems (Burns & Santos, 1995; Dixon, 2000; Lave, Frank, Schulberg, & Kamlet, 1998). Active and continuous mental health treatment is the best defense against relapse, as well as the best offense for recovery. In turn, relapse prevention protects against recidivism (Beck & Maruschak, 2001; Draine & Solomon, 1994; Monahan et al., 2001; Solomon, Draine, & Meyerson, 1994; Ventura, Cassel, Jacoby, & Huang, 1998).

As incarcerated populations grow in size and in their representation of mental illness, state and local officials are looking for ways to respond. Ways that comply with constitutional requirements and legal mandates, fit the contours of a fragmented public system, which relies increasingly on the private sector, and that are affordable. Their affordability is perhaps the most limiting and vexing challenge, especially in contemporary times of huge state budget shortfalls. The needs of mentally disordered offenders are complex and multi-dimensional, often including addiction problems and some form of personality disorder, and they are expensive if managed comprehensively. It is unlikely that there will ever be enough public funding, even in more prosperous times, to meet all their needs. For this reason, it is vital that policy makers carefully invest available funds in responses that are most likely to address needs that produce health and justice outcomes most valued by society.

Advanced here is the argument that the most sensible way to respond to the needs of offenders with mental illness is to treat their needs as an investment, and to evaluate alternative responses to their needs in terms of their yields (or rates of return measured in health and justice outcomes). States and local governments that seek to maximize the social return on their investments will invest both in high yielding interventions and systemic and structural changes that affect the depreciation rates of the outcomes produced by these investments. For example, it makes no social or economic sense to invest public dollars in stabilizing chronic mental health problems of inmates while they are incarcerated and then lose this “outcome” by gaps in treatment when the person moves from prison or jail to the community. Everyone loses, repeatedly, when this type of disjointed (and irrational) investment strategy is followed. From a social investment perspective, the challenge facing public officials is not mental illness in correctional or community settings; but, rather how to use scarce public dollars, intended to address mental health problems, to produce and protect mental health as a means for promoting prosocial behavior.

This paper has three parts. The first part profiles the male special needs population in New Jersey prisons. These profiles describe behavioral health and criminal justice characteristics of 2715 male inmates with mental health problems, and are used to identify the scope and nature of the public’s investment opportunity. The next part describes the costs associated with possible “investments”. The special needs population is classified by need and placement difficulty, and then matched to reentry and community-based treatment programs. Costs are estimated for reentry planning and community-based treatment for the first year post-release. The third part recommends an investment strategy and a set of operational changes that might minimize the loss and maximize the return on the public’s investment dollar in mental health.

2. Need and placement difficulty profile of male prison inmates

While there is widespread agreement among public officials, the public, and researchers that mental illness is present among a sizable minority of inmates, there is considerably less consensus regarding the prevalence, range, and severity of the illness, and whether the illness and its treatment predated incarceration. The evidence that is available, while sketchy, pertains mostly to the prevalence of mental illness within the incarcerated population. Federal statistics show that approximately 16% of jail and prison inmates have some type of mental health problem (Ditton, 1999). Recent reports prepared by the Human Rights Watch and National Commission on Correctional Healthcare estimate higher rates of mental illness (Human Rights Watch, 2003; National Commission on Correctional Health Care, 2001). It is also known that inmates with mental health problems are likely to have co-occurring addiction problems. Roughly 60% of state prison inmates with mental health problems reportedly were under the influence of drugs or alcohol at the time of their index arrest (Ditton, 1999). This estimate is consistent with epidemiologic evidence on the co-morbidity between mental illness and addiction problems (Bartels et al., 1993; Drake, Rosenberg, & Mueser, 1996; Kessler et al., 1996). Combined together, these estimates suggest that mental illness is concentrated in the incarcerated population and it ranges in type of disorder and co-morbidity pattern. But these are rather “soft” estimates, lacking the detail and specificity required for informed policy making and planning. In this next section, for a single state prison system, information is provided on the demographic, behavioral health, and the criminal history characteristics of all prison inmates treated for mental health problems at a point in time.

2.1. Profile of male special needs inmates in New Jersey prisons

2.1.1. Methods

2.1.1.1. Data Source

Data are based on the universe of adult special needs inmates located in the nine (male) New Jersey prisons on August 10, 2002. Of the approximately 16,700 inmates in these facilities, roughly 2700 inmates (or 16%) were classified as special needs inmates. These are individuals who need or receive “mental health treatment of some type” while in prison (Cevasco & Moratti, 2001). An inmate may be placed on the special needs roster at intake or any time during a prison stay. For each special needs inmate, the following data were extracted from the Department of Correction’s management information system: age, race/ethnicity, active and inactive psychiatric diagnoses (Axes I and II), current sentence length, convictions involving arson, violence, or sex crime, and re-incarceration due to violation of parole.

2.1.1.2 Classification scheme for need and placement difficulty

Need was determined by active Axis I psychiatric disorder. Inmates with a serious mental illness, inclusive of schizophrenia, other psychotic disorder, major depression, mood disorder, or bipolar disorder (McAlpine & Mechanic, 2000; Swanson, Holzer, Ganju, & Jono, 1990) were classified as high need. Placement difficulty was determined by type of conviction. An inmate was classified as high placement difficulty if he was serving time for a violent offense. A violent offense might include a physical or sexual assault, murder, arson, or other crimes that involve physical harm.

2.1.2. Results

Approximately 67% of the 2715 special needs inmates in New Jersey prisons for men were identified as having a serious mental illness. Psychiatric disorders among the special needs population were distributed as follows: 26.4% were diagnosed with schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders; 41.1% with major depression, major mood disorder, or bipolar; 16.8% with depression, dysthymia, obsessive compulsive disorder, PTSD; 12.8% with panic disorder, anxiety disorder, somatoform disorders, impulse control disorders, or ADD/ADHD; and 3.4% had an Axis II diagnosis only.

2.1.2.1. Demographic characteristics

Special needs inmates were most likely to be African American (46%) and between the ages of 24 and 40 (50%). The race/ethnic characteristics were similar among special needs inmates with and without a serious mental illness (Table 1). Special needs inmates without a serious mental illness were slightly older (mean age 37.4 years) than those inmates with a serious mental illness (mean age 35.95 years) (t=3.43, df=2713, p<.01).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of all special needs inmates in New Jersey prisons for men on August 10, 2002

| Demographic characteristics | All male special needs inmates | |

|---|---|---|

| Special needs with SMI (n=1833) | Special needs without SMI (n=882) | |

| Race/Hispanic origin | ||

| White | 40.3% | 40.0% |

| African American | 46.2% | 45.5% |

| Hispanic | 10.1% | 9.8% |

| American Indian | 0.4% | 0.5% |

| Unknown | 2.9% | 4.3% |

| Age | ||

| 24 or younger | 15.7% | 10.7% |

| 25–39 | 49.8% | 49.3% |

| 40–54 | 30.0% | 33.9% |

| 55 or older | 4.6% | 6.1% |

2.1.2.2 Behavior health characteristics

Approximately 25% of special needs inmates with and without a serious mental illness were diagnosed with a co-occurring personality disorder (Table 2). Personality disorders include all cluster types, such as antisocial, narcissistic, paranoid, and avoidant. Mental retardation was rarely diagnosed in either of the special needs groups. Substance abuse or dependence was common among special needs inmates (41%), but more prevalent for inmates with serious mental illness, compared to those without a serious mental illness (χ2=7.68, df=1, p<.01).

Table 2.

Behavioral health characteristics of all special needs inmates in New Jersey prisons for men on August 10, 2002

| Behavioral health characteristics | All male special needs inmates | |

|---|---|---|

| Special needs with SMI (n=1833) | Special needs without SMI (n=882) | |

| Personality disorder | 25.2% | 23.6% |

| Mental retardation | 1.7% | 1.1% |

| Alcohol/substance abuse or dependence | 42.8% | 37.2% |

2.1.2.3. Criminal history characteristics

The criminal histories of special needs inmates with and without a serious mental illness were similar (Table 3). The majority of special needs inmates were serving long sentences (more than 5 years) associated with a violent offense. Compared to special needs inmates with a serious mental illness, a larger proportion of inmates without a serious mental illness was re-arrested on a parole violation (χ2=4.47, df=1, p<.05).

Table 3.

Criminal history characteristics of all special needs inmates in New Jersey prisons for men on August 10, 2002

| Criminal history characteristics | All male special needs inmates | |

|---|---|---|

| Special needs with SMI (n=1833) | Special needs without SMI (n=882) | |

| Sentence longer than 5 years | 69.2% | 69.4% |

| Convicted of arson | 2.6% | 1.2% |

| Convicted of violent offense | 54.7% | 53.6% |

| Convicted of sex offense | 15.5% | 15.2% |

| Rearrested on parole violation | 31.8% | 35.8% |

2.1.2.4. Need–placement difficulty clusters

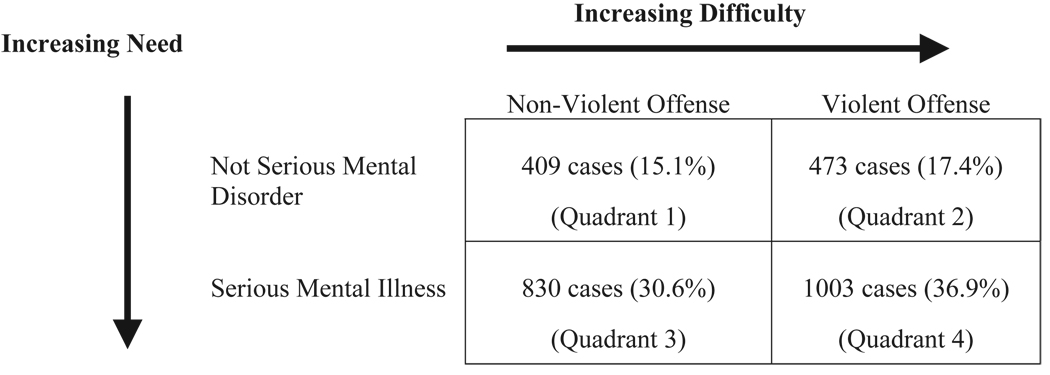

Considerable variation exists in the need and placement difficulty characteristics of special needs inmates. There is not one type of special needs inmate, just like there is not one type of person with mental illness in the community. These individuals vary in their behavioral health problems (e.g., serious versus non-serious mental disorder, presence of addiction problems, personality disorder) and criminal histories (e.g., violent versus non-violent). The heterogeneity within this population of inmates is illustrated by classifying special needs inmates by type of mental illness (non-serious mental illness or serious mental illness) and type of conviction (non-violent or violent) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Need–placement difficulty classification of male special needs inmates.

The highest need and placement difficulty cluster, representing 37% of special needs inmates, has a serious mental illness and is serving time for a violent offense. The majority of these inmates (51%) had at least one prior psychiatric hospitalization, and 38% has a co-occurring addiction problem. An example of a high need–high placement difficulty inmate is

Case W, a male inmate in his early 40s, who has a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, antisocial personality disorder, and polysubstance abuse. He has had multiple admissions to psychiatric hospitals and an extended admission to a forensic hospital during his incarceration. His criminal history predates puberty and includes multiple convictions for violent crimes. He has been in and out of prison for 20 years. In prison he has committed dozens of institutional infractions and spent over five years in administrative segregation for assaults and failure to obey. His treatment compliance in prison has been fair.

The cluster of high need and low placement difficulty inmates appears in quadrant 3. These inmates, representing 31% of special needs inmates, are not currently serving time for a violent offense but they may have a violence history. Roughly half of these inmates had a prior psychiatric hospitalization and (48%) have a co-occurring addiction problem, as reflected in the following case study:

Case X is a male inmate in his early 40s with a major depressive disorder, with psychotic features. He has attempted suicide four times in five years, including one attempt while incarcerated. He was incarcerated for burglary and drug related convictions. He has no official record of violent crime. His history of treatment compliance is very good. He has no institutional infractions while incarcerated.

Inmates with a non-serious mental disorder (low need) are divided into two placement difficulty groups: those with low (non-violent conviction) and high (violent conviction) placement difficulty, and appear in quadrants 1 and 2, respectively. Roughly one-quarter of the inmates in these two clusters had a prior psychiatric hospitalization. An alcohol or substance abuse diagnosis was more common in the low need–low placement group (46%), compared to the low need–high placement difficulty group (30%). Cases Y and Z represent the profiles of low need–placement difficulty and low need–low placement difficulty clusters, respectively.

Case Y is a male inmate in his mid 30s with an adjustment disorder. He has no prior mental health treatment history or history of suicidality. His criminal career began at age 15. He has been in prison for 15 years and is serving a 25-year sentence for robbery and manslaughter. He has several institutional infractions for failure to comply with rules and using abusive language but has not spent any time in administrative segregation. His treatment compliance is reported as very good.

Case Z, a male in his late 20s, has a diagnosis of adjustment disorder. He has no history of psychiatric hospitalization, suicidality, or outpatient mental health treatment. His is currently serving a short sentence for resisting arrest and eluding police. He has no official record of violent crime or juvenile delinquency. His treatment compliance in prison is rated very good. He has no institutional infractions.

2.2. Reentry planning and community-based treatment: The costs of the investment

Building reentry and treatment capacity with health and justice outcomes in mind involves both anticipating the needs and placement challenges among inmates to-be-released and budgeting for programs that respond to their needs and criminal behaviors. The resources needed to coordinate reentry and to manage the behavioral health problems in the community are likely to vary among inmates with different needs and placement challenges. Some cases may require more coordination and treatment effort because the inmate’s mental health problems are more serious and his criminal problems more extreme. Finding appropriate treatment in the community and maintaining treatment engagement for individuals with these profiles is likely to be time consuming and subject to considerable uncertainty. By contrast, some inmates with special needs will be relatively easy to place because their mental health problems are straightforward and their criminal histories less problematic. In this section, the cost of two different investments in both reentry and community-based programming are estimated for the population of special needs inmates described above.

2.2.1. Methods

2.2.1.1. Community reentry and reentry participation rates

Cost estimates are sensitive to rates of release and reentry program participation. According to the NJDOC, 20% of the special needs population is released each year. It was assumed that 95% of these inmates would participate in the reentry program. The cost of reentry programming was also estimated assuming a 5-percentage point increase and decrease in the release rate (i.e., 15, 20, and 25) and a 5- and 10-percentage point decrease in the rate of participation (95, 90, and 85).

2.2.1.2. Reentry planning tiers

Reentry planning varies by the length of the coordination period. There are four reentry coordination tiers:

Super Extensive Reentry Coordination (Tier 4). Eighteen months of specialized coordination by a mental health professional with forensic experience, beginning 6 months before release. The average case receives 85 hours of coordination effort.

Extensive Reentry Coordination (Tier 3). Twelve months of specialized coordination by a mental health professional with forensic experience, beginning 6 months before release. The average case receives 65 hours of coordination effort.

Basic Reentry Coordination (Tier 2). Six months of specialized coordination by a mental health professional with forensic experience, beginning 3 months before release. The average case receives 45 hours of coordination effort.

Limited Appointment Coordination (Tier 1). Four weeks of engagement by a mental health professional with forensic experience, beginning 2 weeks before release. Responsibility is limited to scheduling an appointment with an outside mental health provider and following up on any problems. The average case receives 8 hours of service coordination.

2.2.1.3. Community treatment alternatives

Community treatment includes treatment for mental health and addiction problems. It is assumed that 60% of special needs inmates will need outpatient addiction treatment. There are four community treatment tiers, which reflect the care options available in New Jersey, with the first two tiers funded by the state but delivered under contract by private agencies:

Assertive Community Treatment (Tier 4). Case management according to the PACT model (4), which includes at least one face-to-face meeting each week with a case manager, alcohol or drug abuse counseling, and medication monitoring by a psychiatrist and nurse.

Enhanced Intensive Case Management Services (Tier 3). Case management that includes five face-to-face meetings with a case manager per month, one group therapy session each week, one medication monitoring visit with a psychiatrist per month, plus one individual outpatient drug/alcohol treatment visit and three group sessions per week (6 months).

Basic Case Management Services (Tier 2). Case management that includes 2 hours of face-to-face time with a case manager each month, one group therapy session each week, and one medication monitoring visit with a psychiatrist per month, plus one individual outpatient drug/alcohol treatment visit and three group sessions per week (6 months).

Non-Case Managed Care (Tier 1). Two outpatient individual counseling sessions in first month, one group therapy session per week for 6 months, and one medication monitoring visit with a psychiatrist per month, plus one individual outpatient drug/alcohol treatment visit and three group sessions per week (6 months).

2.2.1.4. Unit cost estimation

Two techniques were used to value services. Unit costs were derived for reentry planning and were based on variable cost structures. For community-based services and medications, New Jersey Medicaid rates, adjusted for state subsidies, were used as a proxy measure of costs borne by the state. Cost estimates were provided by the Chief Financial Analyst for the New Jersey Division of Mental Health Services.

2.2.1.5. Reentry planning

Currently, there are no reentry programs in operation in New Jersey that provides the level of reentry coordination proposed here. For this reason, unit costs had to be estimated by drawing on the cost experience of other existing programs. Unit costs for the reentry tiers reflect variable costs (e.g., salary, fringe benefits, travel costs, telephone, and office supplies) and were based on two sources of data. First, data on program costs were obtained from two programs (one located in New Jersey, which serves only women prisoners and provides 4 weeks of coordination only, the other in Massachusetts, which provides 6 months of coordination to prisoners with serious mental illness only). The program directors provided detail information on salary and travel costs associated with their staff. Information on salary costs for forensic social workers was also obtained from local and state agencies located in New Jersey. For the State of New Jersey, the competitive salary for an MSW social worker with 2 years forensic experience is US$38,000. Because salary costs for social workers were 94% of total program costs, cost estimates were also constructed assuming an annual social worker salary of US$40,000 and US$42,000. Second, work effort calculations were constructed based on interviews with 10 case coordinators affiliated with reentry programs located in Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and New Jersey.

2.2.1.6. Community-based services

Medicaid reimbursement rates and state subsidy rates were used to estimate the costs to the State of New Jersey of providing community-based services to special needs inmates with mental health and addiction problems. Rate information was obtained from the Chief Fiscal Analyst for the Department of Mental Health Services and covers the following: assertive community treatment, intensive case management services, medication management visits, group therapy, outpatient substance abuse treatment, and psychotropic medications.

2.2.2. Results

Two need–placement difficulty classification schemas were used to characterize the reentry needs and placement challenges of the estimated 543 male inmates with special needs to-be-released from New Jersey prisons each year. Once classified, need–placement groups are matched to reentry planning tiers. Cost estimates are constructed based on the proportion of inmates in each need–placement group and the unit cost of the reentry tier to which the inmates are assigned. Estimates are provided for two reentry investments: a universal program with 12 months of supervision (as recommended by the National Institute of Corrections (NIC, 2003) and a four-tier program with 1 to 18 months of supervision. Reentry tier groups are then matched to two community-based treatment investments: a universal enhanced intensive case management program and a four-tier community-based program with four treatment options: Assertive Community Treatment, Enhanced Intensive Case Management, Intensive Case Management, and Non-Case Managed Treatment.

2.2.2.1. Investment option 1: Equal need and placement and universal reentry and community treatment programming

This investment option assumes that special needs inmates have equal need and placement challenges. Under this set of assumptions, all special needs inmates would receive the same level of coordination assistance and supervision pre- and post-release. The reentry program would be a universal, one-size-fits-all approach. The distinguishing feature here would be the length of time for coordination and supervision.

Applying the 12-month NIC standard, all special needs inmates would receive 12 months of reentry coordination and supervision. This translates into approximately 65 hours of coordination and supervision distributed over 12 months. Reentry planning would consist of three face-to-face meetings with a case coordinator at the prison (first 6 months) and 18 face-to-face meetings in the community (last 6 months). The remainder of the care coordinator’s time is allocated to travel, coordination and consultation, and paperwork. If this standard is applied to all 543 special needs inmates expected to be released in 2003, reentry planning is estimated to cost approximately US$900,000 annually (Table 4).1 Providing all special needs inmates with 12 months of enhanced case management following release is estimated to cost US$7.3 million, 80% of which is associated with mental health treatment. Reentry coordination and community-based case management would overlap for 3 months post-release to facilitate the transition to the community. If problems or delays in coverage arise during this period, the reentry coordinator would be responsible for coordinating case conferences and community resources.

Table 4.

Estimated unit and total costs of alternative reentry and community-based programs

| Assumptions about the special needs population |

Length of reentry coordination | Total program cost |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 month US$353/case |

6 months US$1356/case |

12 months US$1785/case |

18 months US$2643/case |

||

| Equal need and placement difficulty |

N=516, US$921,060 |

US$921,060 | |||

| Unequal need and placement difficulty |

N=78, US$27,534 |

N=90, US$122,040 |

N=158, US$282,030 |

N=190, US$502,170 |

US$933,774 |

| Type of community-based treatment | |||||

| Non-case managed |

Basic Case Management |

Enhanced Case Management |

Assertive Community Treatment |

||

| Mental Health Treatment | US$1880/case | US$6000/case | US$10860/case | US$19985/case | |

| Substance Abuse Treatment | US$3894/case | US$3894/case | US$3894/case | US$3894/case | |

| Equal need and placement difficulty |

N=516, US$5,603,760 |

US$6.8 m | |||

| (SMI and non-SMI) |

N=310, US$1,207,140 |

||||

| Unequal need and placement difficulty |

N=348, US$3,779,280 |

US$4.6 m | |||

| (SMI only) |

N=209, US$813,846 |

||||

| Unequal need and placement difficulty |

N=78, US$146,640 |

N=90, US$540,000 |

N=158, US$1,715,880 |

N=190, US$3,797,150 |

US$7.0 m |

| (SMI and non-SMI) |

N=47, US$183,018 |

N=54, US$210,276 |

N=95, US$369,930 |

||

2.2.2.2. Investment 2: Unequal need and unequal placement difficulty and a four-tier reentry and community-based treatment programming

This investment option assumes that special needs inmates have unequal treatment needs and public safety challenges. In contrast, to the first scheme, it recognizes that mentally disordered inmates have mental disorders that vary in their complexity and service needs. And because more than half of the special needs inmates was found to be serving time for violent offenses, it is likely to be more difficult to place these individuals in the community because of their history of violence. Likewise, they may need more supervision to monitor behavioral tendencies that put the public at risk of harm.

If unequal need and placement were assumed, special needs inmates would be classified in terms of seriousness of mental illness and violent offense history, as shown in Fig. 1. This type of classification scheme suggests a four-tier reentry program, with the high need–high placement difficulty inmates receiving 18 months of coordination and supervision (4 prison visits and 24 community visits); high need–low placement difficulty inmates receiving 12 months; low need–high placement difficulty inmates receiving 6 months (2 prison visits and 12 community visits); and low need–low placement difficulty receiving 1 month (1 visit at prison and in the community). The estimated cost of a four-tier program is US$930,000, slightly more expensive than the universal 12-month program (see Table 4).2

The expected cost of providing community-based treatment to special need inmates depends on who is targeted to receive treatment and whether inmates are matched to services based on their need and placement characteristics. If, for example, community-based treatment is reserved to those special needs inmates with a serious mental illness (67.5%) and they are all assigned to enhanced case management, community-based mental health and addiction services treatment is estimated to cost the State of New Jersey approximately US$4.6 million. Alternatively, matching the higher need–placement tiers (4 through 1) to treatment tiers that provide more intensive case management (tiers 4 through 1), would increase the expected cost by US$2.4 million to US$7.0 million, slightly more than providing all released offenders enhanced case management services (US$6.8 million).

3. Public’s investment in health and justice outcomes

Connecting offenders with mental illness to community mental health services is critically important according to the position statement on post-release planning issued by the American Association of Community Psychiatrists (2000) and the Task Force of the American Psychiatric Association (2000). Yet while important, these standards have not made their way into practice in New Jersey. Most special needs inmates are released without effective linkages to medications or psychiatric services, both of which are essential for maintaining their mental health (C.F. v Terhune, 1999; Wolff, Plemmons, Veysey, & Brandli, 2002). The situation in New Jersey is consistent with anecdotal reports from other states. Delivering seamless care to individuals who move between corrections and the community requires delivering comparable services in both settings and coordinating the actions of corrections, the court, and community service agencies. The cost estimates presented here suggest that New Jersey would need to invest US$5.5 million to US$7.9 million in reentry planning and community-based treatment services to assure the delivery of continuous mental health and addiction services to special needs inmates in the year following their release from prison. The average cost per inmate is approximately US$15,000, which is 40% less than a year in a New Jersey prison.

There are several limitations that warrant attention. First and foremost, it is important to keep in mind that the purpose of this study was to estimate the investment cost of reentry and treatment for special needs inmates located in a single state system. New Jersey is not representative of all states within the United States, or different countries located around the world. Yet the experience in New Jersey is representative of problems that characterize many states and countries: large concentrations of mentally disordered offenders in prisons and jails; a fragmented and under-funded system of care; and spatial concentration of offenders in urban areas that are densely populated and challenged by complex social problems resulting from urban decay and poverty. But our goal was not to provide a single estimate; but rather, to provide a method for estimating the annual costs of alternative investments for integrating ex-offenders with mental health problems into the community post-release. In an effort to make our estimates and approach more generalizable, programs are described in terms of what is provided and who is doing the work. With this level of detail, hours of effort and the skill levels of the staff could be locally adjusted and monetized according to local unit costs.

Another limitation concerns how prisoners were assigned to need–placement groups. This study classified cases on the basis of information on Axis I diagnosis and instant offense. This should be considered a rough approximation of need–placement difficulty. In implementing a multi-tiered reentry and treatment program, more sophisticated placement difficulty and need assessment would be used by clinicians to assign individuals to groups. There are likely to be other clinical and criminogenic factors, such as personality disorder, prior hospitalization, violence history, that may be predictive of need and placement difficulty but which are not routinely available in administrative databases. The classification system used here, as well as more clinically based assignment rules, would benefit from carefully designed validation studies. But, in the absence of this precision, reasonable estimates are needed to inform policy makers of the expected costs of investments in reentry planning and community-based treatment for prisoners returning to the community with mental health problems.

4. Implications for practice, policy, and research

Restoring mental health begins and continues with effective treatment. Research evidence has shown that there are effective programs available for people with mental illness, including assertive community treatment, supportive employment programs, programs for mentally ill, chemical abusers, as well as medications management regimes (Burns & Santos, 1995; Clark et al., 1998; Jerrell & Hu, 1989; Lave et al., 1998; Wolff et al., 1997). In addition, programs are developing that respond to the special needs of people with mental illness and criminal histories (Council of State Governments, 2002; Draine & Solomon, 1994; Hartwell & Orr, 1999; Roskes & Feldman, 1999; The Thresholds, 2001; 25–29). The issue is not whether effective treatment exists but whether it is consistently available to the people who need it, and whether these individuals continuously avail themselves of treatment.

4.1. Investments in treatment as a mechanism for producing mental health and prosocial outcomes

The public (or the state as its agent) cannot afford to fully meet the needs of the special needs population, but there is some level of care that is within the public’s budget. The level of care to be provided will depend in large measure by the size of the investment budget, which depends on how much the public is willing to spend on a standard of care for this population. Once the investment budget is determined, an investment strategy is needed. The three recommendations presented here are intended to set the foundation for the public’s investment strategy. The strategic recommendations include: treatment parity, treatment capacity building, and need–treatment matching.

Strategic Recommendation #1: Treatment Parity—standards of care and treatment opportunities must be equivalent between correctional and community settings.

Whatever treatment opportunities exist on one side of the gate must exist on the other side if treatment is to be consistent and continuous. Treatment must follow the person, and it cannot follow if the capacity is absent or changes with residency status. National standards for correctional health care, such as those recommended by the American Psychiatric Association (2000), may make clinical sense in an abstract social context but they are not socially useful if they are not paired with equivalent service standards in the community.

Strategic Recommendation #2: Treatment Capacity—the degree of specialization within the treatment capacity must fit the case mix of the population.

The complexity and diversity of the treatment capacity is determined in large measure by the variation in need within the special needs population. The “one-size-fits-all” treatment approach is not likely to fit the case mix within the special needs population, which includes people with severe mental illness combined with addiction problems, and personality disorders, those with mild forms of acute depression, and everyone else in between. An array of services contoured to the multi-dimensional nature of the problems within the population will most likely be needed, especially in areas with high concentrations of addiction problems.

Strategic Recommendation #3: Treatment–Problem Matching—screening and assessment must be comprehensive and used to guide the assignment of treatment intensity

Matching people with mental health problems to appropriate treatment services is critical. It requires accurate screening for mental health problems and a comprehensive accounting of co-occurring conditions and violence factors. Without this information, people may be assigned to services that are more or less intensive than what they need, which is wasteful and inconsistent with clinical standards.

4.2. Preserving and protecting the public’s investments in mental health

Mental health is lost when treatment is disrupted or discontinued against clinical advice. Even if these strategic recommendations are adopted, treatment may still lapse for reasons discussed below. The recommendations here are operational in nature and respond to specific obstacles.

4.2.1. Coordination obstacles

Persons are typically released from correctional facilities in an uncoordinated way. Often there is little or no coordination within the correctional facility or between corrections and the community. The first recommendation is intended to facilitate coordination inside the gate.

Operations Recommendation #1: Coordinate release—develop protocols for release that include clearance by the medical unit and the provision of 2 weeks of medication as “personal property.”

Fragmentation exists between the medical and correctional staff. The professional philosophy of these two groups is different in focus and objective, each seeing the inmate and his/her needs differently. Gaps in communication also exist between the correctional staff in charge of release and the medical staff. The lack of communication here can begin the cycle of relapse for inmates who are chronically ill and need medications and continued treatment to maintain their health in the community.

The next recommendation is intended to coordinate treatment activities between correctional and community providers.

Operations Recommendation #2: Agency Responsibility—assign one public agent with the responsibility to coordinate treatment between the correctional and community settings and fund it appropriately.

Treatment is disrupted upon release from a correctional facility because no public agent has responsibility for coordinating treatment between the correctional setting and the community. In the breach, no system accepts responsibility and the public’s investment in inmate health is placed at risk. To protect the public’s investment, some public system must become the responsible agent, and to act responsibly the agent must be adequately funded and provided with the information necessary to make the treatment connections inside and outside the gate.

4.2.2. Information obstacle

Timely and complete medical information is required to respond efficiently and effectively to inmate health problems. The goal here is to remove informational bottlenecks so that clinically appropriate information flows smoothly to providers with minimum duplication and delay.

Operations Recommendation #3: Regulate Information Sharing—develop protocols for sharing health information that are consistent with federal and state protections on privacy and applicable to public and private providers.

Idiosyncratic interpretations of federal and state regulations on confidentiality typically limit information sharing between health providers treating the same person in different settings. Information barriers can impair clinical decision-making and create unnecessary disruptions in treatment.

4.2.3. Eligibility obstacles

There are two types of eligibility obstacles. The first obstacle concerns the difficulty of matching offenders’ treatment histories to the eligibility requirements for community-based services.

Operations Recommendation #4: Eligibility Crosswalk—develop a way to identify case equivalents between community and correctional setting and develop protocols for assuring equal access for those in equal need.

Eligibility for intensive treatment in the community typically requires a serious mental illness and evidence of extreme treatment noncompliance during the past 18 months (typically manifested as a psychiatric hospitalization in the past 18 months). While these criteria are designed to restrict access to those who are most in need of intensive treatment, they are not compatible with the treatment and confinement experience of inmates. While in prison, some inmates may be receiving treatment equivalent to that provided by assertive community treatment teams or intensive case managers and their mental health status may depend on receiving that level of treatment. Barring them from appropriate community care because they were incarcerated (and not hospitalized recently) is not consistent with the clinical intent of these programs or the public’s investment in them.

The second eligibility obstacle concerns access to public benefits, especially Medicaid. Access to treatment depends critically on the ability to pay. Federal and state entitlements, including health insurance, are typically suspended or terminated if a person is incarcerated for more than a month. The next recommendation addresses access to public entitlements.

Operations Recommendation #5: Eligibility Continuity—create a mechanism by which inmates can reactivate their Medicaid eligibility prior to release.

Termination or suspension of benefits has serious consequences for reentry planning and community treatment engagement. It can take up to 6 months to get Medicaid and SSI benefits reinstated (after release) but in the interim these individuals need medical care and housing.

These recommendations are consistent with the notion of maximizing the rate of return on the public’s investment in health and justice outcomes. The strategic recommendations provide a framework for structuring a seamless system of care that rationalizes the allocation of resources according to need and placement difficulties. These changes would provide an investment environment that is consistent with getting the most from society’s investments in treatment. Treatment can follow the person if parity exists on both sides of the gate. And the health and justice outcomes that flow from treatment will be maximized if scarce resources are rationed among those with different needs and placement challenges, according to these differences. A treatment–need matching scheme that provides more intensive and extensive services to those special needs inmates with serious mental disorder and violence histories, and then tapers down the services to those with less serious need or public safety risks, is more likely to yield a set of health and justice outcomes that society values enough to fund.

Focusing more on the micro-level, the operations recommendations attempt to bridge the gap between the corrections and the community in an effort to facilitate the movement of people with mental illness between the two settings. They seek to improve coordination and cooperation in ways that reduce obstacles inhibiting the delivery of consistent and continuous treatment. Reducing time lags and information bottlenecks, which are bureaucratic in nature, reduces inefficiency and waste that characterizes the dynamic within the mental health and criminal justice systems and between them.

These structural and operational changes, along with investments in reentry planning and targeted and integrated treatment, to produce a set of health and justice outcomes are more consistent with society’s preferences. Closing the gap between these systems reduces the likelihood of treatment discontinuities and, as a consequence, preserves and protects the public’s yield from these investments. But, to move the public’s investment strategy more in keeping with that outlined here, there must be the political will to change systems, remove structural barriers, and regulate performance. It is not clear that the proposed investment strategy will cost the public more, but it is clear is that the public dollar would be invested differently and more purposefully.

Acknowledgements

Support for this study was provided by the New Jersey Department of Corrections, the New Jersey Division of Mental Health Services, and the Center for Mental Health Services and Criminal Justice Research (Grant #P20 MH66170).

Footnotes

The cost of the reentry program decreases by roughly 5% with each 5-percentage point decline in the participation rate. Similarly, changing the release rate by 5-percentage points changes the program cost by approximately 25%. Increasing the care coordinator’s salary to US$40,000 per year would increase the total program cost by about 5%.

The cost of the reentry program decreases by roughly 5% with each 5-percentage point decline in the participation rate. Similarly, changing the release rate by 5-percentage points changes the program cost by approximately 25%. Increasing the care coordinator’s salary to US$40,000 per year would increase the total program cost by about 5%.

References

- American Association of Community Psychiatrists. Position Statement on Post-Release Planning. 2000. Oct, Retrieved from http://www.wpic.pitt.edu/aacp/finds/postrelease.html. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Psychiatric services in jails and prisons: A task force of the American Psychiatric Association. 2nd ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association Guidelines for Psychiatric Services in Jails and Prisons; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bartels SJ, Teague GB, Drake RE, Clark RE, Bush PW, Noordsky DL. Substance abuse in schizophrenia: Service utilization and costs. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1993;181:227–232. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199304000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AJ, Maruschak LM. Mental health treatment in state prisons. Washington DC: United States Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2001. (No. NCJ-188215) [Google Scholar]

- Burns BJ, Santos AB. Assertive community treatment: An update of randomized trials. Psychiatric Services. 1995;46:669–675. doi: 10.1176/ps.46.7.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cevasco R, Moratti D. The State of Corrections, Proceedings American Correctional Association Annual Conferences, 2000. Lanham, MD: American Correctional Association; 2001. New Jersey’s mental health program; pp. 159–168. [Google Scholar]

- v Terhune CF. U.S. Dist. LEXIS 15677. 1999 67 F. Supp. 2d 401. [Google Scholar]

- Clark RE, Teague GB, Ricketts SK, Bush PW, Xie H, McGuire TG, et al. Cost-effectiveness of assertive community treatment versus standard case management for persons with co-occurring severe mental illness and substance abuse disorders. Health Services Research. 1998;33(50):1285–1308. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Council of State Governments Criminal justice/mental health consensus project 2002. Lexington, KY: Council of State Governments; > [Google Scholar]

- Ditton PM. Mental health and treatment of inmates and probationers. US Department of Justice Special Report. Washington DC: United States Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics; 1999. (No. NCJ-174463) [Google Scholar]

- Dixon L. Assertive community treatment: Twenty-five years of gold. Psychiatric Services. 2000;51(6):759–765. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.6.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draine J, Solomon P. Jail recidivism and the intensity of case management services among homeless persons with mental illness leaving jail. Journal of Psychiatry & Law. 1994;22:245–261. [Google Scholar]

- Drake RE, Rosenberg SD, Mueser KT. Assessing substance use disorder in persons with severe mental illness. In: Drake RE, Mueser KT, editors. Dual diagnosis of major mental illness and substance abuse: Vol. 2. Recent Research and Clinical Implications. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1996. pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Jerrell JM, Hu T. Cost-effectiveness of intensive clinical and case management compared with an existing system of care. Inquiry. 1989 Summer;26:224–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartwell SW, Orr K. The massachusetts forensic transition program for mentally ill offenders reentering the community. Psychiatric Services. 1999;50:1220–1222. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.9.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human Rights Watch. Ill-equipped: U.S. prisons and offenders with mental illness. Washington, DC: Human Rights Watch; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KS, Edlund MJ, Frank RG, Leaf PJ. The epidemiology of co-occurring addictive and mental disorders: Implications for prevention and service utilization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1996;66:17–31. doi: 10.1037/h0080151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lave J, Frank R, Schulberg H, Kamlet MS. Cost-effectiveness of treatments for major depression in primary care practice. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:645–651. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.7.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAlpine DD, Mechanic D. Utilization of specialty mental health care among persons with severe mental illness: The roles of demographics, need, insurance, and risk. Health Services Research. 2000;35(1):277–292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monahan J, Steadman HJ, Silver E, Appelbaum PS, Robbins PC, Mulvey EP, et al. Rethinking risk assessment, The MacArthur study of mental disorder and violence. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- National Commission on Correctional Health Care. The health status of soon-to-be released inmates: A report to Congress. 2001;Vol. 1 Retrieved from http://www.ncchc.org/stbr/Volume1/Health%20Status%20(vol%201).pdf. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Corrections. Transition from prison to community initiative. 2003 Retrieved from http://www.nicic.org/pubs/2002/017520.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Roskes E, Feldman R. A collaborative community-based treatment program for offenders with mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 1999;50(12):1614–1619. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.12.1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon P, Draine J, Meyerson A. Jail recidivism and receipt of community mental health services. Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 1994;45:793–797. doi: 10.1176/ps.45.8.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson JW, Holzer CE, Ganju VK, Jono RT. Violence and psychiatric disorder in the community: Evidence from the epidemiologic catchment area surveys. Hospital and Community Psychiatry. 1990;41(7):761–770. doi: 10.1176/ps.41.7.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Thresholds, State, County Collaborative Jail Link Project, Chicago. Helping mentally ill people break the cycle of jail and homelessness. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52(10):1380–1382. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.10.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ventura LA, Cassel CA, Jacoby JE, Huang B. Case management and recidivism of mentally ill persons released from jail. Psychiatric Services. 1998;49:1330–1337. doi: 10.1176/ps.49.10.1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff N, Helminiak TW, Morse GA, Calsyn RJ, Klinkenberg DW, Trusty ML. Cost-effectiveness of three approaches to case management for homeless mentally ill people. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154(3):341–348. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.3.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff N, Plemmons D, Veysey B, Brandli A. Release planning for inmates with mental illness compared with those who have other chronic illnesses. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53:1469–1471. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.11.1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]