Abstract

The introduction of metagenomics into the field of virology has facilitated the exploration of viral communities in various natural habitats. Understanding the viral ecology of a variety of sample types throughout the biosphere is important per se, but it also has potential applications in clinical and diagnostic virology. However, the procedures used by viral metagenomics may produce technical errors, such as amplification bias, while public viral databases are very limited, which may hamper the determination of the viral diversity in samples. This review considers the current state of viral metagenomics, based on examples from Korean viral metagenomic studies-i.e., rice paddy soil, fermented foods, human gut, seawater, and the near-surface atmosphere. Viral metagenomics has become widespread due to various methodological developments, and much attention has been focused on studies that consider the intrinsic role of viruses that interact with their hosts.

Keywords: bacteriophages, DNA sequence analysis, DNA viruses, environment, metagenomics

Introduction

Viruses are the most abundant and diverse biological entities in the biosphere, and their global numbers have been estimated at 1.2 × 1030 and 2.6 × 1030 in the ocean and soil, respectively [1]. Thus, viruses are key elements that contribute to the life cycles of cellular organisms [2]. However, the study of viral ecology in natural habitats has been limited due to the difficulties of viral culture [3]. The lack of a ubiquitous marker gene, such as the 16S rRNA gene shared by all bacteria and archaea, also hampered our understanding of the genetic diversity of viruses, prior to the introduction of metagenomics into the field of viral ecology [1, 4]. Recently, viral metagenomics has enabled researchers to explore the community structure and diversity of viruses in various natural ecosystems [5]. This methodology depends on a priori knowledge of the viral types that may be present [6, 7].

The first viral metagenome of uncultured marine viral communities was published in 2002 [8], and there have been many subsequent advances in the methodologies (e.g., methods for amplifying the initial viral genomes) and tools used for bioinformatics analysis in viral metagenomics. These technical developments have facilitated explorations of the abundance and diversity of viruses from a wide range of natural habitats in Korea. In Korea, viral metagenomics was applied for the first time to unique samples, including fermented foods and atmospheric samples, as well as habitats where viruses are expected to have significant roles, such as rice paddy soil, seawater, and the human gut. This review describes recent advances in viral metagenomics and provides summaries of studies that have been conducted to characterize Korean viral metagenomes. In addition, the advantages and disadvantages of the most widely used viral DNA amplification methods are discussed, based on empirical knowledge. Further directions for the study of virus-host interactions are also highlighted.

Approaches to Viral Ecology Using Metagenomics

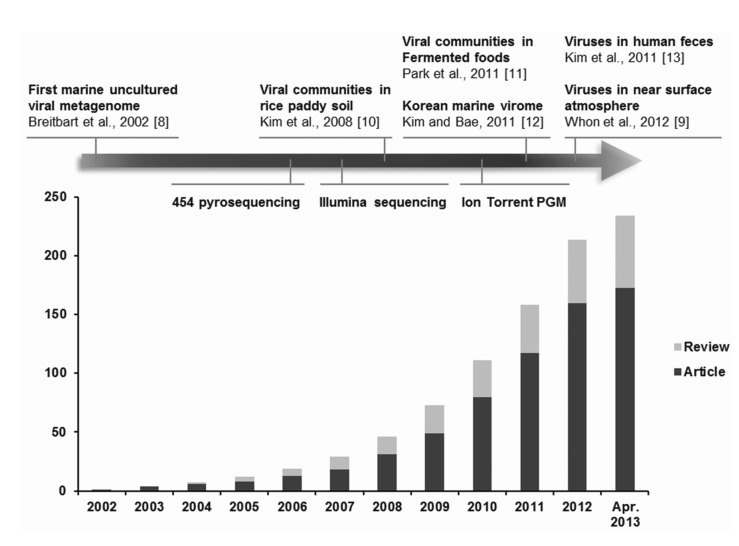

Viral metagenomics is the study of viral metagenomes (known as viromes), which are obtained directly from environmental samples using viral particle purification and shotgun sequencing. Viral metagenomic studies have increased gradually since the expansion of metagenomic approaches to viral ecology; i.e., over 200 (61 reviews) investigations of the viral communities in environmental samples have been published (Fig. 1) [8-13]. In 2002, Breitbart et al. [8] used shotgun library sequencing and reported that the majority of the sequences in marine viral metagenomes shared no similarity with any genes in public databases, which suggested that most environmental viruses remained uncharacterized. This was the first study using viral metagenomic approaches in the field. Subsequently, many studies have surveyed the viral diversity of unexplored habitats using viral metagenomics.

Fig. 1.

Overview of viral metagenomic studies conducted between 2002 and 2013. The cumulative number of publications determined by PubMed searches using the keywords '(virus OR viral OR virome) AND (metagenome OR metagenomics)' is shown on the y-axis. The first viral metagenome and Korean metagenomes (highlighted by arrows), as well as the technical development of high-throughput sequencing platforms (below the highlighted arrow), are shown with the year of publication and/or public release.

Cultivation in a host is usually necessary to obtain a virus from the environment that is being investigated. However, the application of metagenomics techniques based on genetic information can circumvent this obstacle [14]. Based on the physical characteristics of virions, viral particles can be isolated from environmental samples, which are enriched using a combination of size filtration (e.g., <0.22 µm) and density gradient centrifugation (e.g., 1.35-1.5 g/mL cesium chloride) [14], so that the virome can be obtained from the purified viral particles. There is a lack of evolutionarily conserved genes, such as the prokaryotic 16S ribosomal RNA gene, in viral genomes. Therefore, the fragmented viral metagenomic sequences obtained by whole-genome shotgun DNA sequencing are used to analyze the viral ecology instead. Viral genomes are small (on average, they comprise a few to several dozen kilobases); so, valuable genome coverage can be achieved easily by DNA sequencing. The advent of high-throughput sequencing techniques, such as 454 pyrosequencing and Illumina sequencing, makes it easier to achieve suitable genome coverage at low cost. Indeed, over 90 of either nearly complete or complete novel viral genomes were assembled using these methods in recent studies [9, 10, 15-20]. However, it is inevitable that an amplification step is necessary for small viral genomes prior to DNA sequencing. Linker amplified shotgun library (LASL) and multiple displacement amplification (MDA) are the main methods used to amplify viromes in viral metagenomics. The LASL method, developed by Breitbart et al. [8], PCR-amplifies a virome after adapter attachment to randomly fragmented viral DNAs. The application of adapter attachment is restricted to double-stranded DNA sequences; so, only double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) viruses can be detected using the LASL method. Thus, the dominance of dsDNA tailed bacteriophages was reported initially in uncultured marine viral assemblages [8], as well as other environmental samples, such as kimchi [11], aquatic water [8], and feces [21]. The MDA technique [22] amplifies DNA isothermally using the phi29 polymerase and random hexaprimers and has been used before in microbiology [22]. The high amplification efficiency of this method means that it is suitable for amplification during viral metagenomics applications. Particularly, the phi29 polymerase of the MDA technique selectively amplifies circular genomes (estimated at 100 times) [10], and it has facilitated the discovery of abundant single-stranded DNA and RNA viruses in environmental samples [23, 24] (described in detail below).

Assignment of Viral Sequences Based on Their Metadata and Potential Hosts

The analysis of viral metagenome data using bioinformatics is one of the most challenging aspects of viral metagenomics. One million to 1 billion reads of viral metagenomic sequences are typically generated by high-throughput sequencing platforms (with an average read length of 350-400 bp using 454 GS-FLX Titanium and 2 × 150 bp using Illumina HiSeq 2500). After removing any low-quality, redundant, and chimeric sequences, the viral sequences are compared to sequences in public databases (e.g., the GenBank non-redundant nucleotide database, MG-RAST, and CAMERA) using BLAST [25] or USEARCH [26]. The identification of viral sequences based on significant amino acid similarity (E-value of <10-3) was first described by Breitbart et al. [8], and it has since been extended to the exploration of environmental viromes, although the E-score applied to viral metagenomic studies appears to be regarded as "a loose standard" [27].

Most of the environmental viromes detected by viral metagenomics are defined as orphan (unassigned) sequences. The majority of viral sequences shares no amino acid similarity with previously observed genes (average 40% to 50%, occasionally up to 90%, of sequences); so, they are characterized as "unknown" [5]. Comparisons of viral sequences with the data in public databases have demonstrated that little is known about environmental viruses. Thus, the majority of the unassigned sequences in viral metagenomes is often regarded as "junk sequences" due to a lack of suitable bioinformatics tools and viral databases for their characterization [1, 28]. At present, the viral databases are biased toward animal and plant viruses, although viruses that infect prokaryotes (bacteriophages) are sparsely represented. Most of the latter are restricted to phages that infect bacteria belonging to the phyla Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, and Actinobacteria [29, 30]. Moreover, even "known" viral sequences share low amino acid similarities (<50%) with viral protein sequences [9, 11, 13, 31]; so, the majority of environmental viruses representing novel viral species and their viral diversity is much greater than considered previously. The observation of a high percentage of ORFans (open reading frames with no homologs in known genes in the databases) in viral genomes [32] also supports the novelty of environmental viromes. Thus, researchers could discover novel viruses in orphan sequence pools that currently remain "untapped resources." These findings indicate our current lack of knowledge about viral genetic information and emphasize the need for physiological studies of viruses to understand viral ecology based on genomic data.

Viral Metagenomes from Korean Samples

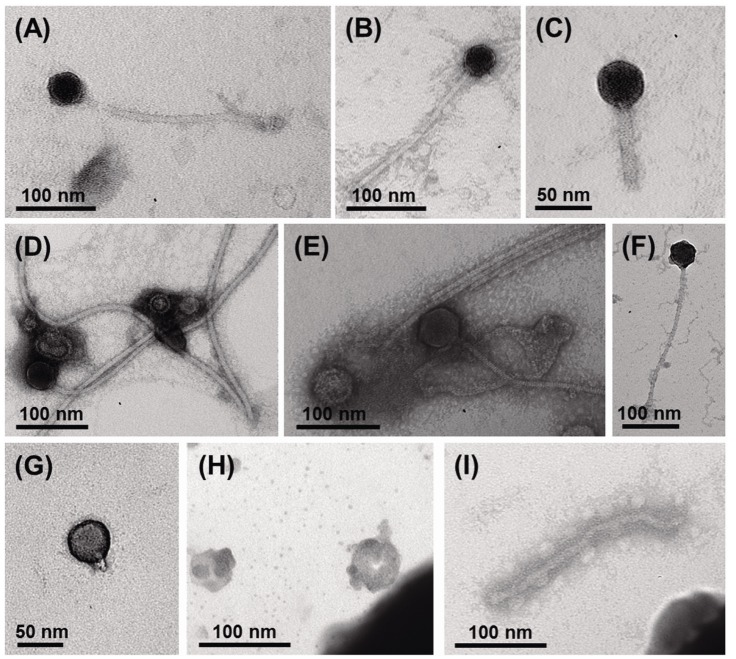

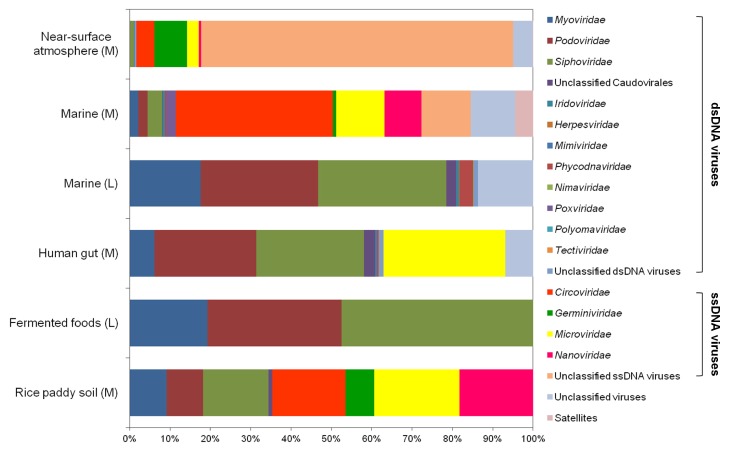

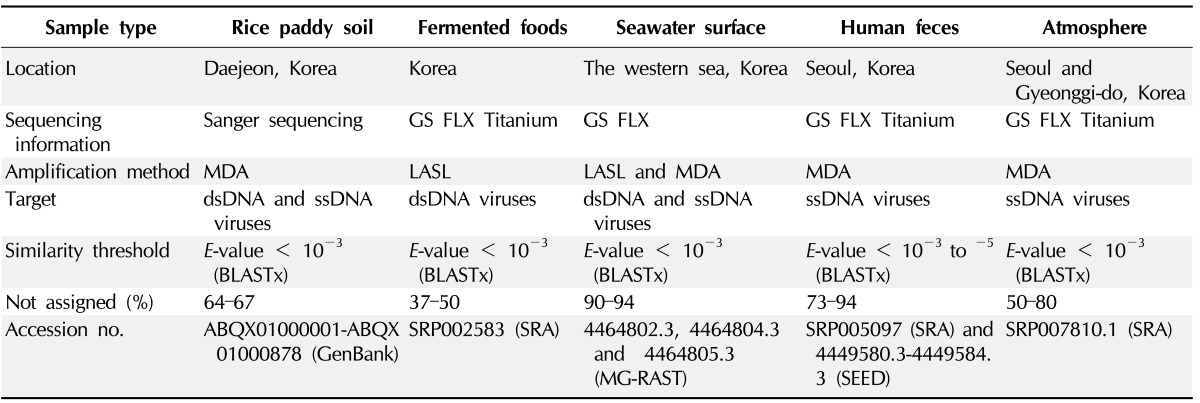

Using viral metagenomic approaches, viral diversity and abundance have been investigated in various natural ecosystems in Korea, including rice paddy soil, fermented foods, the human gut, seawater, and the near-surface atmosphere (Table 1). The morphologies of environmental viruses have been imaged using transmission electron microscopy (Fig. 2). Sipho- and podo-like tailed viruses were found in fermented foods (Fig. 2A-2C), while non-tailed small viruses were detected in the near-surface atmosphere (Fig. 2G-2I). Various types of tailed, non-tailed, circular, and long linear viruses were found in the human gut (Fig. 2D-2F). In general, the virions ranged in size from 30 to 60 nm. In agreement with the results of previous viral metagenomic studies [23, 31], over half of the sequences in the Korean environmental viromes were described as orphan sequences, based on comparisons with viral proteins in public databases (Table 1). Most of the sequences identified were assigned to the Siphoviridae, Podoviridae, and Myoviridae families of dsDNA viruses and the Circoviridae, Germiniviridae, Nanoviridae, and Microviridae families of ssDNA viruses (Fig. 3). The first viral metagenomic study in Korea surveyed uncultured viral assemblages in rice paddy soil in 2008 [10], where MDA was used with phi29 DNA poly merase and random hexaprimers to amplify viral DNA and to construct clone libraries for metagenome sequencing. The soil was found to contain a rich pool of unknown ssDNA viruses and dsDNA viruses. This study also focused on the effect of MDA amplification on different types of genomic DNA and showed that MDA preferentially amplified circular DNA genomes. This was also demonstrated using an environmental sample from surface seawater [12], where dsDNA viruses alone were retrieved in the LASL library, whereas ssDNA viruses were overwhelmingly represented in the MDA library. Thus, the amplification methods used in viral metagenomics can affect the ratios of viral sequences greatly and lead to inaccurate estimates of viral diversity.

Table 1.

Published Korean viral metagenomics

MDA, multiple displacement amplification; LASL, linker amplified shotgun libraries; dsDNA, double-stranded DNA; ssDNA, single-stranded DNA.

Fig. 2.

Transmission electron micrographs showing the different morphologies of virus particles found in viral samples from Korea. (A-C) Fermented foods. (D-F) Human feces. (G-I) Atmosphere.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of the compositions of viral assemblages identified in Korean environments. The percentages of viral families in each virome indicate the assignments of the metagenomic sequences to viral families. The amplification methods used in each study are designated as follows: M, multiple displacement amplification; L, linker-amplified shotgun library.

Next, Park et al. [11] investigated the abundance and diversity of uncultured viral assemblages in fermented shrimp, kimchi, and sauerkraut-fermented foods that have been consumed for a long time around the world. In contrast to the soil virome, dsDNA bacteriophages from the families Myoviridae, Podoviridae, and Siphoviridae dominated the fermented foods, and they contained a low complexity of viral assemblages compared with other environmental habitats, such as seawater, human feces, marine sediment, and soil. However, it is possible that the viral diversity of the viromes detected in fermented foods may have been constrained to dsDNA viruses by the LASL method.

A large number of unknown microbes, such as bacteria, archaea, microbial eukarya, and viruses, constitute up to 1012 bacteria per gram of feces in the human gastrointestinal tract [33], and it is expected that gut viruses will affect the relationships among viruses, bacteria, and gut epithelial cells [34]. Kim et al. [13] investigated the abundance and diversity of DNA viruses in fecal samples from five healthy Koreans, particularly ssDNA viruses. Using epifluorescence microscopy with SYBR Gold staining [35], the viral abundance ranged from 108 to 109 per gram of feces, which was 10-fold less than the bacterial abundance in many other environments that harbored 10-100-fold more viruses (e.g., aquatic environments). Moreover, the diversity of gut viral assemblages was lower than that of gut bacteria. These results support Reyes et al. [29], who found that viral-microbial interactions in the human intestine could not be described as a predator-prey relationship, and instead, it was referred to as "kill the winner," which was driven by a lytic life cycle.

Airborne viruses are now regarded as major environmental risk factors for complex disease pathogenesis [36-38]. However, the atmosphere remains "one of the last frontiers of biological exploration on Earth" [9]. Using viral metagenomics with an advanced airborne particle sampling system, Whon et al. [9] conducted the first study of the diversity and community composition of airborne viruses in the near-surface atmosphere. The viral abundance in the atmosphere exhibited seasonal changes (increasing from autumn to winter before decreasing until spring) in the range of 106 to 107 viruses per m3, and the temporal variations in viral abundance were inversely correlated with seasonal changes in temperature and absolute humidity. Plant-associated ssDNA geminivirus-related viruses and animal-infecting circoviruses dominated the viral assemblages, with low numbers of nanoviruses and microphages in air viromes, which suggests that airborne viral assemblages are affected greatly by terrestrial plants and animal activities.

The compositions of viral assemblages are determined by how the virome is amplified. Thus, the compositions of the viral assemblages detected in fermented foods and marine samples are biased toward dsDNA viruses, such as sipho-, podo-, and myophages, when the LASL method is used, whereas the viral assemblages detected in rice paddy soil, human gut, marine, and near-surface atmosphere samples contain high proportions of ssDNA viral sequences, due to the use of MDA, as shown in Fig. 3. In addition, the compositions of the viral assemblages characterized in Korean environments tend to depend on their specific microbial features. The human gastrointestinal tract and fermented foods are exposed to massive numbers of gut bacteria and lactic acid bacteria, respectively [39-41]. By contrast, the atmosphere contains far less cellular metabolism and reproductive activity than other environments, such as the soil, seawater, fermented foods, and the human gut [42]. On this basis, the lowest abundance of eukaryotic viruses was observed in the viral assemblages in the human gut and fermented foods, whereas a high abundance of eukaryotic viruses was detected in the near-surface atmosphere. High levels of prokaryote and eukaryote cells are present in rice paddy soil [43] and seawater [44], and so, comparable amounts of bacteriophages and eukaryotic viruses were detected in their viromes.

Discovery of Single-Stranded DNA Viruses in Korean Environments

The development of viral metagenomics has facilitated the discovery of novel, previously undescribed viral species. An artifact of the MDA method is that it selectively amplifies the circular genomes of ssDNA viruses, so that a large number of ssDNA viral sequences have been identified in environmental viromes. Thus, there is great interest in the distribution and host range of ssDNA viruses. In particular, microphages from the family Microviridae have been identified in a wide range of environments [13, 45, 46]. In contrast to the ecology of marine dsDNA phages, marine ssDNA phages in the family Microviridae have distinct spatial and temporal distributions [45]. ssDNA microphages were abundant in the healthy human gut and their genotypes were much more diverse than those reported previously [13]. Moreover, prophage-like elements in the genomes of gut microbes, such as Bacteroides and Prevotella spp., were characterized as a novel subgroup in the family Microviridae [13, 47], while viral sequences from the human gut were clustered with prophage-like elements from Bacteroides and Prevotella spp. [13]. This suggests that Bacteroides and Prevotella spp. are included within the host range of the ssDNA microphages in the human gut [47].

Eukaryotic ssDNA viruses that infect plants and mammals have been identified in many environmental viromes. Circoviruses that are known to infect birds and pigs have also been identified in the viromes of invertebrates and a fish [48, 49], while geminiviruses that cause plant diseases have been detected in whiteflies, which act as insect vectors of plant viruses [50]. A recent study by Whon et al. [9] investigated airborne DNA viral assemblages in near-surface atmosphere samples and showed that a high number of viruses (log 6 to 7 viruses per m3) were present in the air, which were dominated by geminivirus-related viruses. These viruses were identified as plant fungal pathogen-infecting mycoviruses-i.e., Sclerotinia sclerotiorum hypovirulence-associated DNA virus 1-which indicates that the airborne viral assemblages in the near-surface atmosphere may have strong interactions with plants. These results highlight the extensive distribution of ssDNA viruses in a wide range of environments, and their host ranges may be wider than previously recognized. Thus, the discovery of novel genomes of ssDNA viral families in metagenomic studies could revolutionize our knowledge of the ecology and evolution of ssDNA viruses.

Virus-Host Interactions and Emerging Technologies

In the last decade, viral ecologists have focused on community-level analyses of viruses to understand their abundance and genetic diversity in specific environments. The ecological effects of viruses, particularly bacteriophages, are known to control host populations via the "kill the winner system," while they drive mortality and evolutionary change in microorganisms via lateral gene transfer by infecting their host bacteria, although the basic issue of "who infects whom" is poorly understood [2, 29, 51, 52]. In the ocean, for example, viruses regulate the microbial abundance, release dissolved organic matter, and affect global biogeochemical cycles by killing up to 40% of host bacteria per day [53, 54]. In contrast, symbiotic functions of viruses, such as host survival, competition, and protection from pathogenic infections, are beginning to be understood [55], and evidence for a beneficial interaction in phage-host interactions was found in the mammalian gut ecosystem [29, 56]. When host survival is threatened, a variety of environmental factors can trigger prophage induction, and the liberated prophages may become completely virulent [57]. Overall, these studies suggest that prophage induction may responsible for triggering dysbiosis and changes in the microbial population by altering host phenotypes, thereby leading to a new environmental niche.

Traditionally, host culture-dependent techniques, such as plaque assays, have been widely used for the identification of phage and host bacteria interactions. However, plaque assays require isolated host bacteria; so, they are low-throughput methods. This method is also difficult to apply to environmental samples where lysogenic infections are prevalent, because the method relies on observations of visible plaque formations, which are often absent from lysogenic infections [3, 58, 59]. Recently, Deng et al. [52] demonstrated a new technique, known as "viral tagging," for identifying the interactions between cultivated host bacteria and their phages, which used the nucleic acid stain SYBR Gold to generate fluorescently labeled phages, so that the host cells fluoresced with viral tagging, thereby allowing the sorting of virus-tagged cells by flow cytometry [52, 60]. This emerging technique is undoubtedly helpful for not only exploring virus-host interactions in their natural habitats when the method is combined with other experimental tools, such as single viral genomics [61] and phageFISH [62], but also identifying viral receptors in macro-organisms (e.g., the mammalian gut) if the method is combined with a fluorescently labeled receptor protein during histological examinations.

Conclusion

The emergence of viral metagenomics has facilitated advances in virology and allowed us to understand novel aspects of viral ecology. At present, viral metagenomics is a powerful and sensitive technique for detecting viruses that cannot be identified by traditional culture- and sequence-based approaches. Most importantly, viral metagenomics suggests that novel viruses interact constantly with the human population. Thus, viral metagenomics can facilitate the improved surveillance of viral pathogens in the fields of public health and food security. This technique can be used to understand viral ecology by exploring the environmental viromes that are generated by viral metagenomics.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Mid-Career Researcher Program (2011-0028854) and NRF-2012-Forstering Core Leaders of the Future Basic Science Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology.

References

- 1.Mokili JL, Rohwer F, Dutilh BE. Metagenomics and future perspectives in virus discovery. Curr Opin Virol. 2012;2:63–77. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rohwer F, Prangishvili D, Lindell D. Roles of viruses in the environment. Environ Microbiol. 2009;11:2771–2774. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Willner D, Hugenholtz P. From deep sequencing to viral tagging: recent advances in viral metagenomics. Bioessays. 2013;35:436–442. doi: 10.1002/bies.201200174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rohwer F, Edwards R. The Phage Proteomic Tree: a genome-based taxonomy for phage. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:4529–4535. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.16.4529-4535.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosario K, Breitbart M. Exploring the viral world through metagenomics. Curr Opin Virol. 2011;1:289–297. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edwards RA, Rohwer F. Viral metagenomics. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:504–510. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delwart EL. Viral metagenomics. Rev Med Virol. 2007;17:115–131. doi: 10.1002/rmv.532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breitbart M, Salamon P, Andresen B, Mahaffy JM, Segall AM, Mead D, et al. Genomic analysis of uncultured marine viral communities. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:14250–14255. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202488399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whon TW, Kim MS, Roh SW, Shin NR, Lee HW, Bae JW. Metagenomic characterization of airborne viral DNA diversity in the near-surface atmosphere. J Virol. 2012;86:8221–8231. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00293-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim KH, Chang HW, Nam YD, Roh SW, Kim MS, Sung Y, et al. Amplification of uncultured single-stranded DNA viruses from rice paddy soil. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:5975–5985. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01275-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park EJ, Kim KH, Abell GC, Kim MS, Roh SW, Bae JW. Metagenomic analysis of the viral communities in fermented foods. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:1284–1291. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01859-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim KH, Bae JW. Amplification methods bias metagenomic libraries of uncultured single-stranded and double-stranded DNA viruses. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:7663–7668. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00289-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim MS, Park EJ, Roh SW, Bae JW. Diversity and abundance of single-stranded DNA viruses in human feces. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:8062–8070. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06331-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thurber RV, Haynes M, Breitbart M, Wegley L, Rohwer F. Laboratory procedures to generate viral metagenomes. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:470–483. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li L, Kapoor A, Slikas B, Bamidele OS, Wang C, Shaukat S, et al. Multiple diverse circoviruses infect farm animals and are commonly found in human and chimpanzee feces. J Virol. 2010;84:1674–1682. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02109-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.López-Bueno A, Tamames J, Velázquez D, Moya A, Quesada A, Alcamí A. High diversity of the viral community from an Antarctic lake. Science. 2009;326:858–861. doi: 10.1126/science.1179287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blinkova O, Victoria J, Li Y, Keele BF, Sanz C, Ndjango JB, et al. Novel circular DNA viruses in stool samples of wild-living chimpanzees. J Gen Virol. 2010;91(Pt 1):74–86. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.015446-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ng TF, Manire C, Borrowman K, Langer T, Ehrhart L, Breitbart M. Discovery of a novel single-stranded DNA virus from a sea turtle fibropapilloma by using viral metagenomics. J Virol. 2009;83:2500–2509. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01946-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li L, Shan T, Soji OB, Alam MM, Kunz TH, Zaidi SZ, et al. Possible cross-species transmission of circoviruses and cycloviruses among farm animals. J Gen Virol. 2011;92(Pt 4):768–772. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.028704-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosario K, Duffy S, Breitbart M. Diverse circovirus-like genome architectures revealed by environmental metagenomics. J Gen Virol. 2009;90(Pt 10):2418–2424. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.012955-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Breitbart M, Hewson I, Felts B, Mahaffy JM, Nulton J, Salamon P, et al. Metagenomic analyses of an uncultured viral community from human feces. J Bacteriol. 2003;185:6220–6223. doi: 10.1128/JB.185.20.6220-6223.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilbert JA, Zhang K, Neufeld JD. Multiple displacement amplification. In: Kenneth N, editor. Handbook of Hydrocarbon and Lipid Microbiology. Berlin: Springere-Verlag; 2010. pp. 4255–4263. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Angly FE, Felts B, Breitbart M, Salamon P, Edwards RA, Carlson C, et al. The marine viromes of four oceanic regions. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e368. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Culley AI, Lang AS, Suttle CA. Metagenomic analysis of coastal RNA virus communities. Science. 2006;312:1795–1798. doi: 10.1126/science.1127404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Benson DA, Karsch-Mizrachi I, Lipman DJ, Ostell J, Sayers EW. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:D32–D37. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kerfeld CA, Scott KM. Using BLAST to teach "E-value-tionary" concepts. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1001014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wooley JC, Ye Y. Metagenomics: facts and artifacts, and computational challenges. J Comput Sci Technol. 2009;25:71–81. doi: 10.1007/s11390-010-9306-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reyes A, Haynes M, Hanson N, Angly FE, Heath AC, Rohwer F, et al. Viruses in the faecal microbiota of monozygotic twins and their mothers. Nature. 2010;466:334–338. doi: 10.1038/nature09199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kristensen DM, Mushegian AR, Dolja VV, Koonin EV. New dimensions of the virus world discovered through metagenomics. Trends Microbiol. 2010;18:11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosario K, Nilsson C, Lim YW, Ruan Y, Breitbart M. Metagenomic analysis of viruses in reclaimed water. Environ Microbiol. 2009;11:2806–2820. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yin Y, Fischer D. Identification and investigation of ORFans in the viral world. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Turnbaugh PJ, Ley RE, Hamady M, Fraser-Liggett CM, Knight R, Gordon JI. The human microbiome project. Nature. 2007;449:804–810. doi: 10.1038/nature06244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reyes A, Semenkovich NP, Whiteson K, Rohwer F, Gordon JI. Going viral: next-generation sequencing applied to phage populations in the human gut. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2012;10:607–617. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patel A, Noble RT, Steele JA, Schwalbach MS, Hewson I, Fuhrman JA. Virus and prokaryote enumeration from planktonic aquatic environments by epifluorescence microscopy with SYBR Green I. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:269–276. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Foxman EF, Iwasaki A. Genome-virome interactions: examining the role of common viral infections in complex disease. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:254–264. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hurst CJ, Murphy PA. The transmission and prevention of infectious disease. In: Hurst CJ, editor. Modeling Disease Transmission and Its Prevention by Disinfection. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1996. pp. 3–54. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sattar SA, Ijaz MK, Gerba CP. Spread of viral infections by aerosols. Crit Rev Environ Control. 1987;17:89–131. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Humblot C, Guyot JP. Pyrosequencing of tagged 16S rRNA gene amplicons for rapid deciphering of the microbiomes of fermented foods such as pearl millet slurries. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:4354–4361. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00451-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roh SW, Kim KH, Nam YD, Chang HW, Park EJ, Bae JW. Investigation of archaeal and bacterial diversity in fermented seafood using barcoded pyrosequencing. ISME J. 2010;4:1–16. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2009.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qin J, Li R, Raes J, Arumugam M, Burgdorf KS, Manichanh C, et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature. 2010;464:59–65. doi: 10.1038/nature08821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Womack AM, Bohannan BJ, Green JL. Biodiversity and biogeography of the atmosphere. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2010;365:3645–3653. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Elsas JD, Jansson JK, Trevors JT. Modern Soil Microbiology. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wommack KE, Colwell RR. Virioplankton: viruses in aquatic ecosystems. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2000;64:69–114. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.64.1.69-114.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tucker KP, Parsons R, Symonds EM, Breitbart M. Diversity and distribution of single-stranded DNA phages in the North Atlantic Ocean. ISME J. 2011;5:822–830. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2010.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Desnues C, Rodriguez-Brito B, Rayhawk S, Kelley S, Tran T, Haynes M, et al. Biodiversity and biogeography of phages in modern stromatolites and thrombolites. Nature. 2008;452:340–343. doi: 10.1038/nature06735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krupovic M, Forterre P. Microviridae goes temperate: microvirus-related proviruses reside in the genomes of Bacteroidetes. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19893. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lorincz M, Cságola A, Farkas SL, Székely C, Tuboly T. First detection and analysis of a fish circovirus. J Gen Virol. 2011;92(Pt 8):1817–1821. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.031344-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosario K, Marinov M, Stainton D, Kraberger S, Wiltshire EJ, Collings DA, et al. Dragonfly cyclovirus, a novel single-stranded DNA virus discovered in dragonflies (Odonata: Anisoptera) J Gen Virol. 2011;92(Pt 6):1302–1308. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.030338-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ng TF, Duffy S, Polston JE, Bixby E, Vallad GE, Breitbart M. Exploring the diversity of plant DNA viruses and their satellites using vector-enabled metagenomics on whiteflies. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19050. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weinbauer MG. Ecology of prokaryotic viruses. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2004;28:127–181. doi: 10.1016/j.femsre.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Deng L, Gregory A, Yilmaz S, Poulos BT, Hugenholtz P, Sullivan MB. Contrasting life strategies of viruses that infect photo- and heterotrophic bacteria, as revealed by viral tagging. MBio. 2012;3:e00373-12. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00373-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Suttle CA. Viruses in the sea. Nature. 2005;437:356–361. doi: 10.1038/nature04160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Breitbart M. Marine viruses: truth or dare. Ann Rev Mar Sci. 2012;4:425–448. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-120709-142805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roossinck MJ. The good viruses: viral mutualistic symbioses. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:99–108. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Duerkop BA, Clements CV, Rollins D, Rodrigues JL, Hooper LV. A composite bacteriophage alters colonization by an intestinal commensal bacterium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:17621–17626. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206136109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chibani-Chennoufi S, Bruttin A, Dillmann ML, Brüssow H. Phage-host interaction: an ecological perspective. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:3677–3686. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.12.3677-3686.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen J, Novick RP. Phage-mediated intergeneric transfer of toxin genes. Science. 2009;323:139–141. doi: 10.1126/science.1164783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kenzaka T, Nasu M, Tani K. Transfer of a phage T4 gene into Enterobacteriaceae, determined at the single-cell level. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:1274–1277. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02219-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ohno S, Okano H, Tanji Y, Ohashi A, Watanabe K, Takai K, et al. A method for evaluating the host range of bacteriophages using phages fluorescently labeled with 5-ethynyl-2'-deoxyuridine (EdU) Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;95:777–788. doi: 10.1007/s00253-012-4174-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Allen LZ, Ishoey T, Novotny MA, McLean JS, Lasken RS, Williamson SJ. Single virus genomics: a new tool for virus discovery. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17722. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Allers E, Moraru C, Duhaime MB, Beneze E, Solonenko N, Barrero-Canosa J, et al. Single-cell and population level viral infection dynamics revealed by phageFISH, a method to visualize intracellular and free viruses. Environ Microbiol. 2013;15:2306–2318. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]