Abstract

Liver enzyme elevations, as an indicator of liver function, are widely associated with metabolic diseases. Genome-wide population-based association studies have identified a genetic susceptibility to liver enzyme elevations and their related traits; however, the genetic architecture in childhood remains largely unknown. We performed a genome-wide association study to identify new genetic loci for liver enzyme levels in a Korean childhood cohort (n = 484). We observed three novel loci (rs4949718, rs80311637, and rs596406) that were multiply associated with elevated levels of alanine transaminase and aspartate transaminase. Although there are some limitations, including genetic power, additional replication and functional characterization will support the clarity on the genetic contribution that the ST6GALNAC3, ADAMTS9, and CELF2 genes have in childhood liver function.

Keywords: alanine transaminase, aspartate transaminase, childhood liver enzyme, genome-wide association study

Introduction

Plasma liver enzyme tests are broadly applied to predict biochemical liver functions and to diagnose liver diseases. Alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST) are closely associated with hepatocyte damage and steatosis, including non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [1]. Elevated liver enzyme levels, as prospective risk factors, have been reported to be involved in type 2 diabetes and coronary heart disease [2, 3]. However, alkaline phosphatase and gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase are related with biliary, cholestatic, and alcoholic diseases [4].

Overweightedness in childhood or adolescence is persistent in adulthood obesity and is closely associated with adverse health effects, including metabolic diseases [5]. A recent cohort study in Korean adolescents has shown strong associations of liver enzyme levels with a cluster of metabolic syndrome components [6]. Thus, finding genetic markers of liver enzyme levels in childhood would be important for early prediction of liver function and its related disease in adulthood.

Liver enzyme levels are affected by environmental and genetic factors. The heritabilities of liver enzyme levels range from approximately 35% to 61% [7, 8]. To date, two genome-wide association studies (GWASs) in European ancestry populations have identified genetic variants located in multiple genes associated with levels of ALT (HSD17B13-MAPK10, TRIB1, CHUK, and SAMM50), AST (NBPF3-ALPL), and both of them (CPN1 and PNPLA3) [9, 10]. In addition, a meta-analysis identified pleiotropic effects between NAFLD and metabolic traits, such as low-density lipoprotein, high-density lipoprotein, triglyceride, fasting glucose, and insulin resistance [11].

Despite the identification of novel genes or loci associated with liver enzymes in cohort populations, the common variants in childhood are still largely unknown. Here, we present findings from a GWAS in childhood subjects to identify new susceptibility loci for liver enzyme levels.

Methods

Study subjects

Students, aged between 8 and 13 years, were recruited from Gwacheon City and Kyunggi Province from April to June 2010. This study was performed as a part of the Korean Children-Adolescents Study (KoCAS), which has been monitored yearly since their entry into elementary school at age 7 in Gwacheon City or fourth grade at age 10 in Seoul and Gyeonggi Province, Korea. Subjects who were enrolled in a specific diet program or were taking any medications known to affect appetite were excluded from the study. AST and ALT levels were measured in the serum of each subject. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of Seoul Paik Hospital, Inje University, and the Korea Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Informed consent was obtained from the childrens' parents.

Genotyping and quality control

A total of 532 samples were genotyped using the Illumina HumanOmni1-Quad BeadChip (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Samples that revealed the following properties were excluded: genotyping call < 98%, heterozygosity > 30%, sex inconsistency, cryptic first-degree relative, or duplication. A total of 48 subjects were excluded from the sample QC process. Markers with a high missing call rate (> 5%), minor allele frequency < 0.01, and significant deviation from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (p < 1 × 10-6) were also excluded. The remaining 747,076 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were used in subsequent analyses for association.

Association analyses

Genome-wide association was analyzed using the PLINK software (http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/~purcell/plink). The association between genotypes and concentration of liver enzymes in plasma was evaluated with linear regression analysis, controlling for age and body mass index (BMI) as covariates. The Manhattan plots of -log10 (p-value) were made using Haploview v. 4.2. The quantile-quantile plots were generated using R statistics package to assess the overall significance of the genome-wide associations.

Results

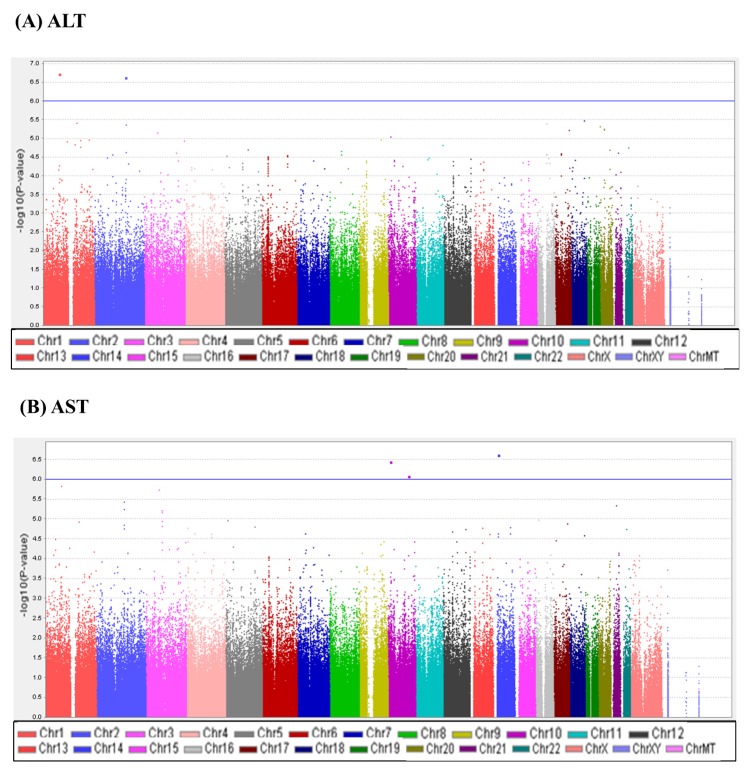

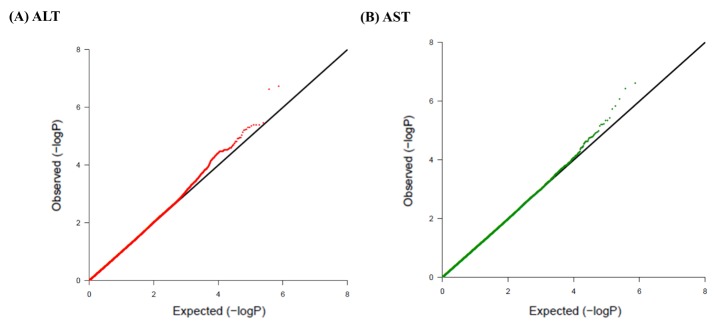

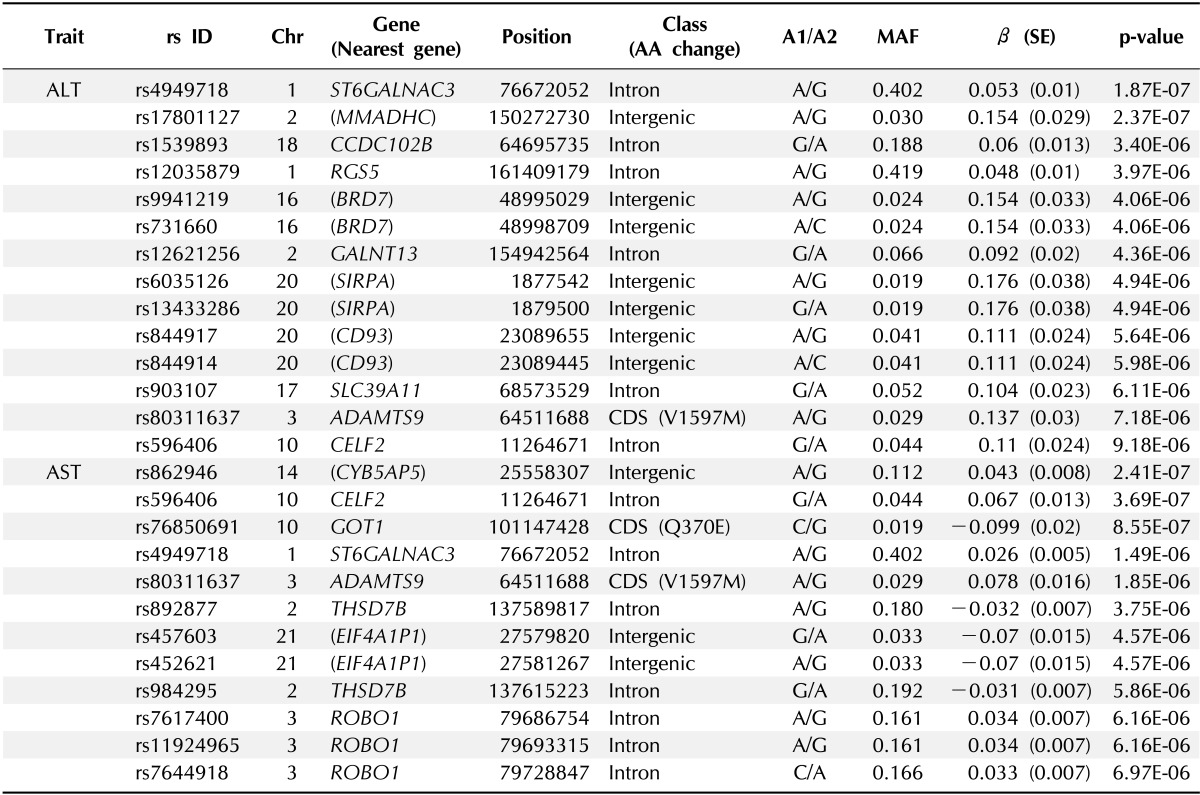

A total of 747,076 SNP genotype assays were tested on the DNA samples of 484 Korean childhood subjects. ALT and AST levels of the subjects according to age and sex are presented in Supplementary Table 1. Linear regression analyses were performed to estimate the p-values for the association between genotype distributions and levels of ALT and AST. Manhattan plots of association analyses of all SNPs with respect to ALT and AST are presented with the chromosomal positions (X-axis) and negative logarithm of p-values (Y-axis) of each SNP (Fig. 1). Quantile-quantile plots comparing the association p-values with those expected for a null distribution are also presented (Fig. 2). The highest-ranked SNPs showing the lowest p-values (p < 1.0 × 10-5) of association with ALT and AST levels are listed in Table 1. In addition, genotype clusters of the SNPs are presented in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Manhattan plots of association results for alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST) levels. Manhattan plots of the genome-wide analyses of association with ALT (A) and AST (B) are based on a total of 484 Korean children. Color scale of X-axis represents chromosomes, and negative logarithms of p-values are shown on the Y-axis.

Fig. 2.

Quantile-quantile plots of association results for alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST) levels in Korean children for 747,076 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Quantile-quantile plots for ALT (A) and AST (B) AST are composed of X-axis and Y-axis indicate the negative log-scale of expected p-values of each SNP and the negative log-scale of the observed p-values, respectively. A straight line indicates the expected results under Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium.

Table 1.

Genetic loci associated with levels of ALT and AST at p < 1 × 10-5 in the GWAS of Korean children (n = 484)

ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transaminase; GWAS, genome-wide association study; Chr, chromosome; AA, amino acid; MAF, minor allele frequency; SE, standard error.

Although there was no SNP satisfying the criteria of genome-wide significance (p < 1.0 × 10-8), we identified three loci (rs4949718, rs80311637, and rs596406 in ST6GALNAC3, ADAMTS9, and CELF2, respectively) that were suggestively associated with levels of ALT and AST. Of these SNPs, rs4949718 was found to be more strongly associated with ALT levels (p = 1.87 × 10-7) but less in AST levels (p = 1.49 × 10-6). The missense rs80311637 (V1597M) and intronic rs596406 SNPs were more strongly associated with an increased risk of AST than ALT.

Discussion

The levels of ALT and AST, known as transaminases, are important indicators for determining hepatocyte injury or hepatocellular diseases. However, ALT is known to be found in the highest level in the liver; thus, ALT levels are more liver-specific indicators [4]. Moreover, it has been reported that ALT levels are more significantly associated with a cluster of metabolic syndrome than AST levels in a Korean adolescent cohort study [6].

In this study, we identified three novel genes (ST6GALNAC3, ADAMTS9, and CELF2) that were multiply associated with elevated levels of ALT and AST. Of the three loci, rs4949718 in the intron region of ST6GALNAC3 yielded the lowest p-value for the association with ALT, compared to AST levels (Table 1). In addition, rs80311637 (ADAMTS9) and rs596406 (CELF2) were shown to be more strongly associated with AST levels, compared to ALT. These results indicate that the liver-specific feature of ALT was not driven as the secondary association for AST. In recent, a previous GWAS in an Amish population identified two genetic variants (rs17209512 and deletion) in glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase 1 (GOT1) that were associated with serum AST. However, the rs17209512 SNP, which is in incomplete LD with rs76850691, was not replicated in our study (Table 1).

For the three multiply associated loci, we performed conditional analyses to test whether the association with the other trait was simply secondary to the primary association (Supplementary Table 2). In these analyses, the association signals on rs4949718 for AST and rs80311637 and rs596406 for ALT were abolished by adjustment of the ALT and AST, respectively. It is assumed that the multiple effects of these loci on ALT and AST resulted from the secondary effects by physiologically correlated features between ALT and AST [12]. In addition, when comparing with BMI-unadjusted data, the association signals in ALT were relatively weaker than those of the BMI-adjusted data. However, there was no significant difference in p-values before and after adjusting for BMI in AST (data not shown).

ST6GALNAC3 encodes a type of sialyltransferase that plays a role in the transfer of sialic acids from cytidine 5' monophospho-N-acetylneuraminic acid (CMP-NeuAc) to the carbohydrate termini of glycoproteins and glycolipids [13]. Previous GWASs have revealed the associations of ST6GALNAC3 SNPs with human electroencephalogram and nicotine dependence [14, 15]; however, there has been no report on an association with liver enzyme levels. Although the association with liver enzymes is still unknown, ST6GALNAC3 has been shown to be associated with subscapular skin-fold thickness, a type of obesity-related trait, in a Korean adult population [16]. Obesity affects elevated liver enzyme levels by inducing inflammatory responses in the liver, accompanied by increases in C-reactive protein [17]. The involvements between obesity and liver enzyme levels have been found in cohort studies [18-20]. Therefore, the association of ST6GALNAC3 with obesity may influence liver enzyme levels indirectly. In addition, ST6GALNAC3 protein interacts with α2-Heremans-Schmid glycoprotein (AHSG), which is also known as fetuin-A, by enzyme-substrate specificity [13]. AHSG is abundantly distributed in serum protein and is produced mainly in the liver, and elevated levels of this protein are associated with the risk of NAFLD [21]. Considering that liver enzyme levels are closely involved indicators in NAFLD [22, 23], the interaction with AHSG might induce an association between ST6GALNAC3 and liver enzyme levels.

ADAMTS9 is a metalloproteinase that plays a role in cleavage of proteoglycans and is expressed in skeletal muscle and pancreas [24]. ADAMTS9 has been reported as a type 2 diabetes susceptibility region in a GWAS [24]. This gene has also shown an association with insulin resistance and impaired beta-cell function in the pancreas [25]. Taken together, the association of ADAMTS9 with liver enzymes might be due to its susceptibility to diabetes and insulin resistance.

CELF2 (also known as CUGBP2) induces the skipping of exon 11 of insulin receptor (IR). The mRNA expression level of exon-skipped IR is significantly lower in liver than in other organs in mouse models [26]. It has been reported that a decrease in the number of IRs on target cells can cause insulin resistance [27]. Therefore, it is assumed that CELF2 affects liver enzyme levels by lowering expression of IR in liver that induces insulin resistance.

In summary, our data demonstrate new multiple associations with ALT and AST levels in a Korean childhood cohort. Further replication and functional studies remain to be done to clarify the genetic factors of liver dysfunction.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (4845-301;4845-302), an intramural grant from the Korea National Institute of Health (2012-N73002-00).

Supplementary materials

Supplementary data including two tables and one figure can be found with this article online at http://www.genominfo.org/src/sm/gni-11-149-s001.pdf.

References

- 1.Li Y, Xing C, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. Genetic variant in PNPLA3 is associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in China. Hepatology. 2012;55:327–328. doi: 10.1002/hep.24659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forlani G, Di Bonito P, Mannucci E, Capaldo B, Genovese S, Orrasch M, et al. Prevalence of elevated liver enzymes in Type 2 diabetes mellitus and its association with the metabolic syndrome. J Endocrinol Invest. 2008;31:146–152. doi: 10.1007/BF03345581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monami M, Bardini G, Lamanna C, Pala L, Cresci B, Francesconi P, et al. Liver enzymes and risk of diabetes and cardiovascular disease: results of the Firenze Bagno a Ripoli (FIBAR) study. Metabolism. 2008;57:387–392. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pratt DS, Kaplan MM. Evaluation of abnormal liver-enzyme results in asymptomatic patients. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1266–1271. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200004273421707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Must A. Does overweight in childhood have an impact on adult health? Nutr Rev. 2003;61:139–142. doi: 10.1301/nr.2003.apr.139-142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee K, Yang JH. Which liver enzymes are better indicators of metabolic syndrome in adolescents: the fifth Korea national health and nutrition examination survey, 2010. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2013;11:229–235. doi: 10.1089/met.2012.0153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bathum L, Petersen HC, Rosholm JU, Hyltoft Petersen P, Vaupel J, Christensen K. Evidence for a substantial genetic influence on biochemical liver function tests: results from a population-based Danish twin study. Clin Chem. 2001;47:81–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whitfield JB, Zhu G, Nestler JE, Heath AC, Martin NG. Genetic covariation between serum gamma-glutamyltransferase activity and cardiovascular risk factors. Clin Chem. 2002;48:1426–1431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuan X, Waterworth D, Perry JR, Lim N, Song K, Chambers JC, et al. Population-based genome-wide association studies reveal six loci influencing plasma levels of liver enzymes. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:520–528. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chambers JC, Zhang W, Sehmi J, Li X, Wass MN, Van der Harst P, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies loci influencing concentrations of liver enzymes in plasma. Nat Genet. 2011;43:1131–1138. doi: 10.1038/ng.970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Speliotes EK, Yerges-Armstrong LM, Wu J, Hernaez R, Kim LJ, Palmer CD, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies variants associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease that have distinct effects on metabolic traits. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1001324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim YJ, Go MJ, Hu C, Hong CB, Kim YK, Lee JY, et al. Large-scale genome-wide association studies in East Asians identify new genetic loci influencing metabolic traits. Nat Genet. 2011;43:990–995. doi: 10.1038/ng.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsuchida A, Ogiso M, Nakamura Y, Kiso M, Furukawa K, Furukawa K. Molecular cloning and expression of human ST6GalNAc III: restricted tissue distribution and substrate specificity. J Biochem. 2005;138:237–243. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvi124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hodgkinson CA, Enoch MA, Srivastava V, Cummins-Oman JS, Ferrier C, Iarikova P, et al. Genome-wide association identifies candidate genes that influence the human electroencephalogram. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:8695–8700. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908134107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uhl GR, Liu QR, Drgon T, Johnson C, Walther D, Rose JE, et al. Molecular genetics of successful smoking cessation: convergent genome-wide association study results. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:683–693. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.6.683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee KT, Byun MJ, Kang KS, Park EW, Lee SH, Cho S, et al. Neuronal genes for subcutaneous fat thickness in human and pig are identified by local genomic sequencing and combined SNP association study. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16356. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kerner A, Avizohar O, Sella R, Bartha P, Zinder O, Markiewicz W, et al. Association between elevated liver enzymes and C-reactive protein: possible hepatic contribution to systemic inflammation in the metabolic syndrome. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:193–197. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000148324.63685.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Franzese A, Vajro P, Argenziano A, Puzziello A, Iannucci MP, Saviano MC, et al. Liver involvement in obese children. Ultrasonography and liver enzyme levels at diagnosis and during follow-up in an Italian population. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:1428–1432. doi: 10.1023/a:1018850223495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luyckx FH, Desaive C, Thiry A, Dewé W, Scheen AJ, Gielen JE, et al. Liver abnormalities in severely obese subjects: effect of drastic weight loss after gastroplasty. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1998;22:222–226. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sabuncu T, Nazligul Y, Karaoglanoglu M, Ucar E, Kilic FB. The effects of sibutramine and orlistat on the ultrasonographic findings, insulin resistance and liver enzyme levels in obese patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Rom J Gastroenterol. 2003;12:189–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haukeland JW, Dahl TB, Yndestad A, Gladhaug IP, Løberg EM, Haaland T, et al. Fetuin A in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: in vivo and in vitro studies. Eur J Endocrinol. 2012;166:503–510. doi: 10.1530/EJE-11-0864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zain SM, Mohamed R, Mahadeva S, Cheah PL, Rampal S, Basu RC, et al. A multi-ethnic study of a PNPLA3 gene variant and its association with disease severity in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Hum Genet. 2012;131:1145–1152. doi: 10.1007/s00439-012-1141-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sookoian S, Pirola CJ. Meta-analysis of the influence of I148M variant of patatin-like phospholipase domain containing 3 gene (PNPLA3) on the susceptibility and histological severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2011;53:1883–1894. doi: 10.1002/hep.24283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zeggini E, Scott LJ, Saxena R, Voight BF, Marchini JL, Hu T, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association data and large-scale replication identifies additional susceptibility loci for type 2 diabetes. Nat Genet. 2008;40:638–645. doi: 10.1038/ng.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trombetta M, Bonetti S, Boselli ML, Miccoli R, Trabetti E, Malerba G, et al. PPARG2 Pro12Ala and ADAMTS9 rs4607103 as "insulin resistance loci" and "insulin secretion loci" in Italian individuals. The GENFIEV study and the Verona Newly Diagnosed Type 2 Diabetes Study (VNDS) 4. Acta Diabetol. 2013;50:401–408. doi: 10.1007/s00592-012-0443-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suzuki H, Takeuchi M, Sugiyama A, Alam AK, Vu LT, Sekiyama Y, et al. Alternative splicing produces structural and functional changes in CUGBP2. BMC Biochem. 2012;13:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-13-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor SI, Kadowaki T, Kadowaki H, Accili D, Cama A, McKeon C. Mutations in insulin-receptor gene in insulin-resistant patients. Diabetes Care. 1990;13:257–279. doi: 10.2337/diacare.13.3.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data including two tables and one figure can be found with this article online at http://www.genominfo.org/src/sm/gni-11-149-s001.pdf.