Abstract

Lymphadenopathy can occur at any stage of HIV infection, with multiple aetiologies including reactive, infectious and malignant. An accurate and timely diagnosis has obvious implications for treatment. We report cryptococcal lymphadenitis as the presenting manifestation of HIV infection. The diagnosis in our patient was eventually confirmed with a lymph node biopsy. Fine needle aspiration cytology has been shown to be a rapid and cost-effective method, which has been used in the diagnosis of lymphadenopathy in HIV infection, and could have been used to make an earlier diagnosis in our patient.

Background

Cryptococcus neoformans is an opportunistic fungus that causes meningitis and pneumonia in patients with HIV infection. Dissemination may cause disease in multiple sites. Cryptococcal lymphadenitis accompanies immune reconstitution syndrome but is uncommonly described in disseminated disease. We report cryptococcal lymphadenitis as the presenting manifestation of HIV infection in a patient who was found to have disseminated disease, but required a lymph node biopsy to establish the cause. The literature suggests that fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) of peripheral lymph nodes is a rapid and safe method to make the diagnosis in HIV-associated lymphadenopathy.

Case presentation

A 38-year-old African-American woman presented to our outpatient clinic with fever, chills, night sweats, headache, mild haemoptysis and progressive neck swelling of 2 weeks duration. She had failed to respond to empiric treatment with azithromycin and prednisone, and reported a 30 pound weight loss.

The patient's medical history was notable for migraine headaches and hypertension. There was no history of tobacco, alcohol or injection drug use. She was monogamous with a male partner and reported consistent use of barrier protection. Her last sexual intercourse had reportedly been 1 year ago. She had two teenage children who were healthy.

On examination, she was ill-appearing and febrile to 38.5°C. Her blood pressure was 133/80 mm Hg, pulse 95/min, respiratory rate of 18/min with an O2 saturation of 100% on room air. Head and neck examination revealed enlarged right posterior cervical lymph nodes which were firm, but non-tender and freely mobile. Smaller submandibular and supraclavicular nodes were palpated bilaterally. Examination of the oropharynx showed no pharyngeal oedema or exudate, and mucous membranes were moist. There was no evidence of oral thrush. Neck was supple. Her cardiovascular examination was normal, lungs were clear to auscultation, and abdominal examination was unremarkable with no hepatosplenomegaly. Neurological examination was completely unremarkable and no skin lesions were appreciated.

Investigations

Initial laboratory data showed a white cell count of 3.9 K/μL (4–10.5), with an absolute neutrophil count of 2800 (1400–6500), absolute lymphocyte count of 600 (1200–3400), and 3% band forms. Haemoglobin was 9 g/dL (12.5–16) with a mean corpuscular volume of 68 (78–100). The platelet count, creatinine and liver functions tests, including bilirubin, were all within normal limits.

CT scan of the neck and chest was obtained which revealed prominent bilateral posterior cervical, supraclavicular, axillary and mediastinal adenopathy, as well as nodular pleural thickening in the posterior aspect of the lungs.

HIV ELISA and western blot were positive. A CD4 count was profoundly depressed at 18/μL. HIV viral load, measured by branched DNA testing was 6696 copies (Bayer, Tarrytown, New York). Blood cultures grew yeast, subsequently identified as Cryptococcus neoformans. Serum cryptococcal antigen was positive at 1 : 512. Lumbar puncture revealed 11 white , and 7 red blood cells. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) India ink stain was negative, cryptococcal antigen in CSF was positive at 1 : 4 and CSF culture grew few Cryptococcus neoformans, sensitive to fluconazole and voriconazole.

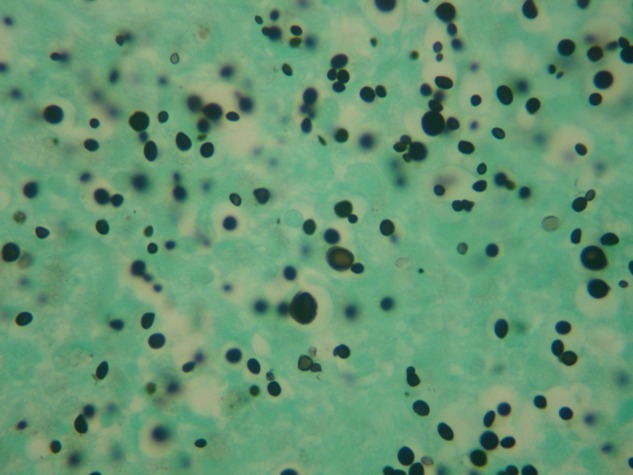

On hospital day 6, the patient underwent a lymph node biopsy, which showed necrotising granulomas with evidence of numerous cryptococci on H&E and Gomori's methenamine silver stain. (The patient's lymph node histopathology is shown in figure 1.) Lymph node fungal culture grew many Cryptococcus neoformans organisms. Acid-fast bacilli smear and culture of a specimen of expectorated sputum as well as the lymph node were negative. There was no pathological evidence of malignancy in the lymph node.

Figure 1.

Microscopic images of cryptococcal organisms within a lymph node. Gomori's methenamine silver stain (×40 magnification).

Differential diagnosis

Our patient was diagnosed with disseminated cryptococcal infection with fungaemia, central nervous system and lymph node involvement.

Other infectious aetiologies were excluded by positive blood cultures for Cryptococcus, as well as lymph node biopsy, which also excluded malignancy as a cause of lymphadenitis in this immunocompromised host.

Treatment

The patient was initially treated with liposomal amphotericin B and 5-flucytosine for 2 weeks, followed by 8 weeks of oral fluconazole. The hospital course was complicated by acute kidney injury secondary to amphotericin. Her discharge medications included fluconazole 400 mg daily, as well as dapsone 100 mg daily and azithromycin 1200 mg/week for Pneumocystis jiroveci and Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare complex prophylaxis, respectively.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient was discharged after 18 days in the hospital.

Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) was initiated 2 months after initial diagnosis with efavirenz/emtricitabine/tenofovir. Her CD4 count at that time was 19 cells/µL, with a viral load of 30 650 copies, and serum cryptococcal antigen titer of 1 : 1024. She tolerated therapy well with a few gastrointestinal side effects.

She returned to work, and lymphadenopathy was absent at her 3 month follow-up. At her 8 month follow-up CD4 count was 204 cells/μL, HIV viral load was undetectable (<75 copies) and cryptococcal antigen in the serum was 1 : 256. There was no evidence of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS).

Discussion

Lymphadenopathy is a common finding in HIV infection, and is often one of the earliest manifestations of HIV infection. Causes of HIV-associated lymphadenopathy include non-specific follicular hyperplasia, opportunistic infection and malignancy. It is critical to establish the cause(s) of lymphadenopathy in patients infected with HIV. Various researchers have reported on different causes of lymphadenopathy worldwide. With the advent of HAART, the incidence of cryptococcal disease has declined, from 24 to 66 cases/1000 persons in the USA in 1992 to 2–7/1000 in 2000.1

In a large Indian study, Kamana et al2 analysed lymph node specimen from 300 HIV-infected individuals. Most patients had tuberculosis or reactive lymphadenitis; cryptococcus was found in only 4/300 lymph node samples (1.3%). Studies from India and Thailand have had similar findings. Not surprisingly, there are epidemiological variations in the aetiology of neck masses between developing and developed countries.3

Numerous case reports describe the importance of cryptococcus in the IRIS associated with the initiation of HAART.4 Typical presentations include lymphadenitis, central nervous system infection and pulmonary disease.5–7 Srinivasan et al reviewed 15 cases of cryptococcal lymphadenitis, all diagnosed by FNAC. In their review, 8 of the 15 patients had HIV infection, and 5/8 biopsies showed necrotising granulomas as was observed in our patient.8

We present this case to remind clinicians of the importance of establishing a diagnosis when patients present with unexplained adenopathy. FNAC has been shown to be a safe and effective tool even in the presence of HIV infection.9 10 It has also been shown to be valuable in diagnosing cryptococcal lymphadenitis, even in patients with a negative latex agglutination test,11 and is safe for patients with malignancy.12 FNAC is more cost-effective than excisional biopsy ($75–$350 vs $1200–$2500). The primary drawback is the risk of sampling error, which can contribute to false-negative results.

Learning points.

Cryptococcal infection should be a diagnostic consideration for lymphadenopathy in any patient, regardless of known HIV infection.

This case highlights the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion in order to diagnose and treat in a timely manner.

Fine needle aspiration remains a rapid, accurate and cost-effective tool in the diagnosis of lymphadenopathy. It is likely that this patient would have been diagnosed sooner had an FNAC been performed earlier.

Footnotes

Contributors: PD and MG were involved in the writing and editing the manuscript. NN was involved in interpretation and reporting of the lymph node histopathology, and also provided the caption for the lymph node pathology photograph.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Mirza SA, Phelan M, Rimland D, et al. The changing epidemiology of crytococcosis: an update from population-based active surveillance in 2 large metropolitan areas, 1999–2000. Clin Infect Dis 2003;2013:789–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kamana NK, Wanchu A, Sachdeva RK, et al. Tuberculosis is the leading cause of lymphadenopathy in HIV-infected persons in India: results of a fine-needle aspiration analysis. Scand J Infect Dis 2010;2013:827–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmad T, Naeem M, Ahmad S, et al. Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) and neck swellings in the surgical outpatient. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad 2008;2013:30–2 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tahir M, Sharma SK, Sinha S, et al. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in a patient with cryptococcal lymphadenitis as the first presentation of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J Postgrad Med 2007;2013:250–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skiest DJ, Hester LJ, Hardy RD. Cryptococcal immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome: report of four cases in three patients and review of the literature. J Infect 2005;2013:e289–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsai HC, Chen YS, Lee SR, et al. Cervical lymphadenitis caused by Cryptococcus-related immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome. QJ Med 2010;2013:531–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuttiatt V, Sreenivasa P, Garg I, et al. Cryptococcal lymphadenitis and immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome: current considerations. Scand J Infect Dis 2011;2013:664–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Srinivasan R, Nalini G, Shifa R, et al. Cryptococcal lymphadenitis diagnosed by fine needle aspiration cytology: a review of 15 cases. Acta Cytol 2010;2013:1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vanisri HR, Nandini NM, Sunila R. Fine-needle aspiration cytology findings in human immunodeficiency virus lymphadenopathy. Indian J Pathol Microbiol 2008;2013:481–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarma PK, Chowhan AK, Agrawal V. Fine needle aspiration cytology in HIV-related lymphadenopathy: experience at a single centre in north India. Cytopathology 2010;2013:234–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu X, Bi X-L, Wu J-H, et al. Disseminated cryptococcal lymphadenitis with negative latex agglutination test. Chin Med J 2012;2013:2393–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burnand KG, Young AE, Lucas J, et al. The new Aird's companion in surgical studies. 3rd edn China: Elsevier, 2005 [Google Scholar]