Abstract

We presented a case of a cholecystoduodenal fistula in a patient 4 years post-Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. The patient presented with biliary colic symptoms after a stone became impacted in the fistula and outflow through the cystic duct was intermittently obstructed by a second stone. The fistulous tract was taken down with a cholecystectomy and duodenum repaired with a modified Graham patch.

Background

Gallstone formation and associated complications, such as biliary colic, cholecystitis and choledocholithiasis, are seen with increased frequency after surgically induced weight loss.1–5 Despite this, comparing the risks and benefits of adding a cholecystectomy to the weight loss procedure has led to the general consensus that the gallbladder be left in place unless there are associated biliary symptoms occurring preoperatively.2 With surgical weight loss procedures becoming increasingly popular, surgical treatment of complications from gallstones in this patient population will become commonplace.6 Given the altered gastrointestinal anatomy associated with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography is generally not considered a feasible diagnostic and treatment modality.7 Therefore, accurate diagnosis of biliary tract disease relies heavily on preoperative imaging and intraoperative findings.

Case presentation

A 44-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with a 12-h history of fever and unrelenting right upper quadrant and epigastric pain (6 of 10). Additionally, she described a 2-month history of constant dull right upper quadrant pain with intermittent increases in the pain, described as sharp in nature, after fatty or high-protein meals. She denied weight loss, jaundice, acholic stools, haematocheia or melena. Her only previous surgery was Roux-en-Y gastric bypass performed 4 years prior. Aside from obesity and a previous history of alcoholism, she denied any medical problems and took no medications.

Examination revealed an afebrile, non-toxic woman with a body mass index of 29.9. Blood pressure was 96/63 with a heart rate of 95. There was mild right upper quadrant tenderness and an enlarged liver palpable several centimetres below the right costal margin. The abdomen was non-distended with laparoscopic surgical scars present. She lacked pallor, jaundice, sclericterus, skin rashes or sensory deficits.

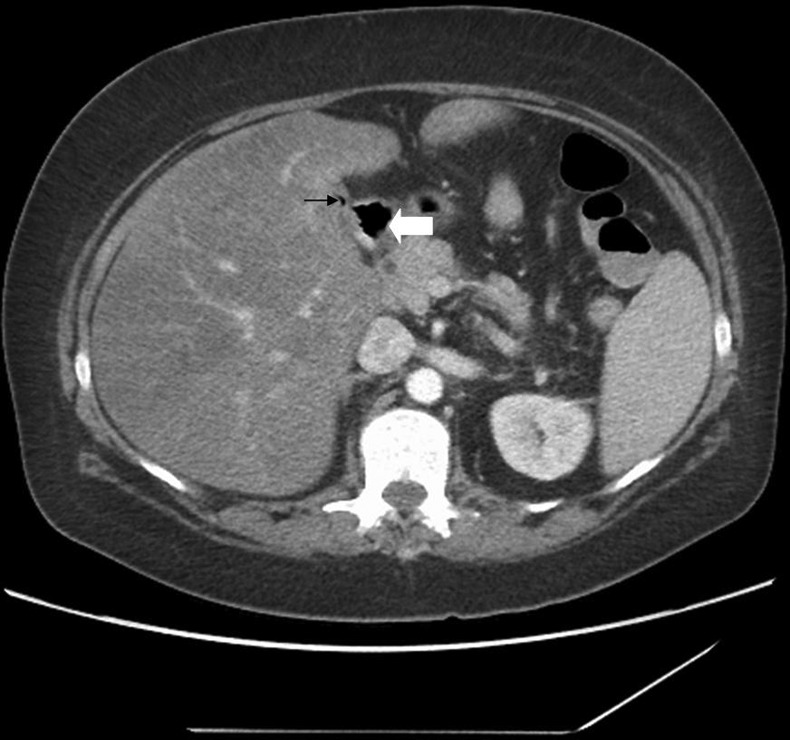

Laboratory results identified a leucocytosis (13 400), normocytic anaemia (haemoglobin 8.5) and mild protein malnutrition (albumin 2.7). Hypokalaemia was the only electrolyte abnormality. Alkaline phosphatase (238) and aspartate aminotransferase (141) were mildly elevated and total bilirubin was 2.1. Kidney function was normal, international normalised ratio was 1.5 and partial thromboplastin time was 35. Oral and intravenous contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen and pelvis identified postsurgical changes consistent with Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, fatty infiltration of the liver resulting in hepatomegaly, and a gas-filled, contracted gallbladder suspicious for a cholecystoenteric fistula (figures 1 and 2). Right upper quadrant ultrasound showed a thick-walled, contracted gallbladder with multiple echogenic foci thought to represent bubbles of air, as opposed to stones.

Figure 1.

CT of the abdomen and pelvis with PO and IV contrast. A thin black arrow identifies the cholecystoduodenal fistula.

Figure 2.

CT slice of the abdomen with PO and IV contrast. A thin black arrow identifies the fistula. A thick white arrow marks the duodenal stump.

The patient was admitted and was started on intravenous ceftriaxone and metronidazole with a nil per os order. The leucocytosis resolved within 24 h of initiating antibiotics. The gallbladder was not visualised on hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid (HIDA) scan. MR cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) reflected the findings of the CT and revealed no adenopathy or biliary ductal dilation (figure 3).

Figure 3.

MR cholangiopancreatography image. A thick black arrow marks the fistula, and a thick white arrow marks the duodenal stump. A thin black arrow marks the distal common bile duct.

Treatment

The patient was taken to the operating room for diagnostic laparoscopy. Inspection of the liver revealed cirrhosis and marked adhesions between the omentum and bowel to the under surface of the liver. Initially, adhesions were taken down laparoscopically, however, after finding a contracted, fibrotic, intrahepatic gallbladder without a critical view of safety, the decision to convert to an open procedure was made. Further dissection revealed a fibrotic band of tissue (fistula) tethering the midbody of the gallbladder to the adjacent duodenum. A cholangiogram revealed two routes of contrast filling into the duodenum, with the fistula being the most prominent (figure 4). There were no filling defects in the biliary system, but a filling defect, likely representing an impacted stone, was seen at the opening of the fistulous tract. The previously identified fibrous band correlated with the fistula seen on cholangiogram. This was sharply taken down exposing gallbladder mucosa proximally and duodenal mucosa distally. The gallbladder was cored from the fossa with suture ligation of the cystic duct and artery. The mucosa of the duodenotomy was closed in two layers: 3–0 Vycril followed by 3–0 silk Lembert sutures with tails left long to form a modified Graham patch using omentum. A 19F Blake drain was placed in the Morrison's pouch and the peritoneum was irrigated and closed.

Figure 4.

Intraoperative cholangiogram. A thin arrow with a long tail identifies the contracted gallbladder. The thick black arrow marks the fistulous track with proximal filling defect representing the impacted stone. The thin arrow with a short tail marks the distal common bile duct and the thick white arrow identifies the proximal gastric remnant.

Outcome and follow-up

Postoperatively, the patient's course was uncomplicated. The drain was removed and she was discharged home on postoperative day 5. Pathology identified a fibrotic gallbladder with cholelithiasis, transmural chronic inflammation and a cholecystoenteric fistula that measured 2 cm in length with a 0.8 cm diameter gallbladder orifice. Impacted within the proximal portion of the fistula was a dark green multifaceted 6 mm stone with surrounding focal haemorrhagic and inflammatory mucosal changes. A second stone was found free in the neck of the gallbladder but there was no associated cystic duct obstruction.

Discussion

Cholelithiasis occurs at a frequency of 10–20% in the general population with the great majority of cases remaining asymptomatic.8 Obesity and rapid weight loss are known risk factors for the development of gallstones, hence, surgical weight loss procedures are associated with an increased risk of gallstone disease. Development of cholelithiasis after gastric bypass is estimated to be as high as 52.8%.1 Cholecystectomy from complications related to gallstones is required in 6.8% to 15.7% of postgastric bypass patients, which is significantly higher than the general population.2–5

Cholecystoenteric fistulas are predominantly discussed in the literature under the topic of gallstone ileus. Intestinal obstruction secondary to a large enteric gallstone is a rare phenomenon occurring in less than 6/1000 cases of cholelithiasis.9 As a single gallstone enlarges to a larger size, often greater than 2 cm, it rests fixed in the most dependent location within the gallbladder. The weight of the excessive stone causes pressure necrosis of the wall of the gallbladder. This necrosis induces an intense inflammatory response which is the underlying pathophysiology of the fistula formation. A surrounding hollow viscous, most often the duodenum but alternatively the stomach, jejunum or colon, becomes involved in the inflammatory process and as the gallstone erodes through the wall of the gallbladder, a fistula is formed to the adjacent bowel.10

Based on the prominence of the fistula compared to the common bile duct in our patient, as seen on cholangiogram and measured on pathological evaluation, it is evident that the cholecystoduodenal fistula had become the primary route for bile drainage into the duodenum. The gallbladder was therefore continually compressed, which explains its contracted appearance. The chronic symptoms were likely related to bacterial reflux through the fistula resulting in chronic cholecystitis. The pathological evaluation of the gallbladder specimen identified a 6 mm gallstone impacted in the proximal portion of the fistula. As seen on the cholangiogram, this stone significantly decreased the flow of contrast through the fistula, which was measured to have an 8 mm diameter. Any gallbladder wall oedema would readily obstruct the fistulous track at the location of the impacted stone. The intermittent acute pain, we hypothesise, was secondary to intermittent obstruction of the cystic duct by the second stone, which was found free within the gallbladder on pathological evaluation. Essentially, the patient was experiencing biliary colic due to intermittent obstruction of the cystic duct when the fistula was no longer an outflow track. The unrelenting pain symptoms, fever and leucocytosis at presentation likely represents the onset of acute cholecystitis as the cystic duct became persistently obstructed, explaining the lack of gallbladder visualisation on HIDA scan. Significant gallbladder distension was not found intraoperatively, suggesting subsequent relief of the outflow obstruction allowing decompression, which is supported by the flow of contrast seen on the intraoperative cholangiogram.

Our modified Graham patch repair of the duodenotomy proved successful as drain output remained non-bilious until its removal. At outpatient follow-up the patient remained symptom free and tolerant of a low fat diet.

Learning points.

Gallstone disease is common after surgically induced weight loss.

Complications relating to gallstones, such as acute cholecystitis, ascending cholangitis and cholecystoenteric fistulas, are more common after bariatric surgery.

The altered gastrointestinal anatomy after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass limits the use of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography as a diagnostic and treatment modality for complications of gallstone disease.

A modified Graham patch (omental patch) after mucosal closure of the duodenotomy created after cholecystoduodenal fistula takedown is an effective repair technique.

Footnotes

Contributors: CWE collected data for the manuscript. BCH is the primary author of the manuscript. LHB is the secondary author and editor of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Iglezias Brandao DO, Adami CE, da Silva BB. Impact of rapid weight reduction on risk of cholelithiasis after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg 2003;2013:625–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warschkow R, Tarantino I, Ukegjini K, et al. Concomitant cholecystectomy during laparoscopic roux-en-y gastric bypass in obese patients is not justified: a meta-analysis. Obes Surg 2013;2013:397–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nagem R, Lazaro-da-Silva A. Cholecystolithiasis after gastric bypass: a clinical, biochemical, and ultrasonographic 3-year follow-up study. Obes Surg 2012;2013:1594–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wattchow DA, Hall JC, Whiting MJ, et al. Prevalence and treatment of gallstones after gastric bypass surgery for morbid obesity. BMJ 1983;2013:763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Villegas L, Schneider B, Provost D, et al. Is routine cholecystectomy required during laparoscopic gastric bypass? Obes Surg 2004;2013:206–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nguyen NT, Masoomi H, Magno CP, et al. Trends in use of bariatric surgery, 2003–2008. J Am Coll Surg 2011;2013:261–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marks JM, Ponsky JL. Chapter 3 Endoscopy and endoscopic intervention. In: Zinner MJ, Ashley SW. eds. Maingot's abdominal operations. 12th edn. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakorafas GH, Milingos D, Peros G. Asymptomatic cholelithiasis: is cholecystectomy really needed? A critical reappraisal 15 years after the introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Dig Dis Sci 2007;2013:1313–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saund M, Soybel DI. Chapter 50 Ileus and bowel obstruction. In: Mulholland MW, Lillemoe KD, Doherty GM, Maier RV, Upchurch GR. eds. Greenfield's surgery. 4th edn. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Masannat Y, Masannat Y, Shatnawei A. Gallstone ileus: a review. Mt Sinai J Med 2006;2013:1132–4 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]