Abstract

Hypoxic hepatitis (HH) most commonly results from haemodynamic instability and disruption of hepatic flow. The vast majority of cases are caused by cardiac failure, respiratory failure and septic shock. We report a case of HH, acute liver failure, acute kidney failure and progressive thrombocytopenia that developed following a hypotensive episode in a patient treated with intravenous diltiazem for a newly developed atrial fibrillation (A-fib). The pre-existing liver diseases, including chronic alcohol use and liver congestion secondary to right heart dysfunction, might have predisposed the patient to the development of HH. The patient was given supportive treatment and experienced full recovery of both liver and kidney function. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of HH that occurred following ventricular rate control for acute A-fib. For patients with underlying liver diseases, closer blood pressure monitoring is warranted during diltiazem infusion.

Background

Hypoxic hepatitis (HH), also known as ischaemic hepatitis or shock liver, is an acute liver injury resulting from liver hypoxia.1 It has been reported that HH occurs in 1% of the patients admitted to the intensive care unit and the prognosis has been poor.2 3

Pathologically, HH is characterised by centrilobular liver cell necrosis, which clinically manifests by a massive increase in serum aminotransferase.4 5 Generally, HH is preceded by an acute event that abruptly decreases the oxygen availability of the liver, in the presence of a pre-existing disease that causes chronic liver hypoxia.2 5 Cardiac failure, respiratory failure and septic shock account for more than 90% of the cases of HH.4 Although disruption of hepatic blood flow has been described as the most important mechanism in the development of HH, a shock state is found in only 50% of cases.4 Here we report a case of HH, acute liver failure, acute kidney failure and progressive thrombocytopenia following intravenous diltiazem infusion for newly onset rapid atrial fibrillation (A-fib). The patient responded to supportive treatment and experienced full recovery of liver and kidney function.

Case presentation

A 70-year-old German man presented to the emergency department of our hospital with palpitations, shortness of breath, loose bowel movements and flu-like symptoms including productive cough with yellowish sputum for 3– 4 days. Medical history included coronary artery disease complicated by a right ventricular infarction status post a successful six vessel coronary artery bypass grafting 17 years prior, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, sleep apnoea (non-compliant with continuous positive airway pressure), prostate cancer treated with radiation and transurethral resection of the prostate and oesophageal strictures status postpneumatic dilation. The patient admitted to a 6–8 ounce daily alcohol intake. He denied history of renal dysfunction or abnormal liver enzymes.

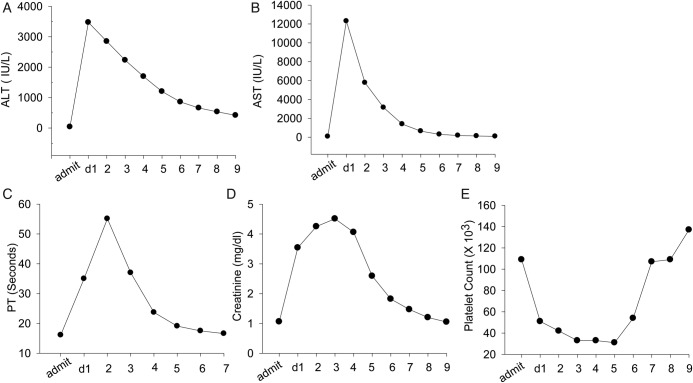

On admission, vital signs were blood pressure (BP) 121/81 mm Hg, heart rate (HR) 135/min, temperature 36.8 °C and respiratory rate 32/min. A physical examination revealed oral thrush, irregular heart rhythm, tachypnoea, clear breath sounds, no palpable organomegaly and no significant peripheral oedema. Lab tests showed haemoglobin 15.2 g/dL, haematocrit 43.9%, mean corpuscular volume (MCV) 103.6 fL, white cell count (WBC) 9.3×103/µL, neutrophil 73.5%, platelet 109 000/µL, normal serum folate and B12 levels, creatine (Cr) 1.06 mg/dL, blood urea nitrogen 22 mg/dL, brain naturetic peptide 462 pg/mL. ECG monitoring showed A-fib and atrial flutter with rapid ventricular response (RVR). The ECG showed ejection fraction 59%, wall motion abnormalities consistent with disease in the distribution of the right coronary artery, moderate mitral, tricuspid and aortic regurgitation, increase in the left and right atrial volume and mild increase in right ventricular systolic pressure. The chest X-ray showed no signs of infection or pulmonary oedema. Enoxaparin was administered and the patient was put on telemetry. Diltiazem was given according to the standard diltiazem protocol, that is, bolus injection of 20 mg (0.25 mg/kg) followed by an intravenous infusion at a rate of 10 mg/h. BP was measured 15 min after bolus, every 30 min×2 times, then every 1 h×2 times, then every 4 h during the intravenous infusion. Approximately 15 h after the initiation of intravenous diltiazem, the patient was found to be hypotensive (BP of 80/50 mm Hg), which was rapidly reversed by stopping the diltiazem flow. The day after admission, the patient deteriorated. He gradually developed bilateral lower extremity oedema, mild epistaxis and a productive cough with blood-streaked sputum. He was afebrile, normotensive and fully oriented. Complete blood count revealed WBC 16.6×103/µL, neutrophil 89.4%, haemoglobin 13.2 g/dL, haematocrit 40.7%, MCV 104.5 fL and platelet 51 000/µL. The liver function test showed alanine transaminase (ALT) 3472 IU/L, aspartate transaminase (AST) 12 307 IU/L, albumin 3.1 g/dL, prealbumin 17 mg/dL, total bilirubin 2.3 mg/dL, direct bilirubin 0.8 mg/dL, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 7753 IU/L, serum ammonia 74 µmol/L. The patient also had rapid elevation of Cr, prolongation of prothrombin time (PT) and progressive thrombocytopenia (figure 1). An abdominal ultrasound revealed mild ascites and small bilateral pleural effusions. MRI was not performed during the hospitalisation due to kidney failure. A Technetium-99m renal scan showed normal blood flow to both kidneys and markedly impaired cortical function unrelated to obstruction. Serum acetaminophen level was within normal limits and the hepatitis virus panel was negative. Screening for diffuse intravascular coagulation, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, antinuclear antibody, haemolysis and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura was negative. A chest CT scan without contrast showed multiple patchy areas of infiltrate with inflammatory appearance. Sputum culture grew Moraxella catarrhalis. Blood, urine and stool culture were all negative.

Figure 1.

Change of aminotrasferase (ALT), alanine aminotransferase (AST), prothrombin time (PT), creatine and platelet count of the patient since admission. (A) Normal serum ALT on admission (admit), abrupt increase on postadmission day 1 (d1) and gradual decrease over 8 days (2–9). (B–E): changes of AST, PT, creatine and platelet.

Treatment

The patient was given intravenous piperacillin/tazobactam for his pneumonia, along with supportive treatment. His anticoagulation was held initially because of coagulopathy secondary to liver dysfunction.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient recovered and his liver enzyme and renal functions returned to normal gradually. The outpatient MRI 4 weeks after discharge showed mild cirrhotic changes in the liver. The patient was readmitted 8 weeks later with exacerbation of mitral, tricuspid and aortic regurgitation, and uncontrolled HR. He underwent atrioventricular node ablation and pacemaker placement. Currently, he has been in a stable condition.

Discussion

HH is most commonly caused by acute circulation disturbances and reduced hepatic blood flow, although shock occurs in only 50% of patients.3 Being an organ with dual blood supply, a normal liver is not susceptible to ischaemic injury. Generally, HH results from a combination of low blood flow and one or more pre-existing hepatic conditions, including venous congestion and portal hypertension.6 7

To our knowledge, there has been no reported case of HH following acute A-fib and diltiazem infusion in the English literature. In this case, the diagnosis of HH was based on the following: (1) hypotension episode before the evidence of liver injury; (2) there was no evidence of viral hepatitis, acetaminophen overdose, autoimmune hepatitis, occlusion of hepatic vessels or other conditions that might cause the massive increases in serum aminotransferase levels; (3) laboratory findings that were characteristic of HH, including a striking increase in aminotransferase levels exceeding 1000 IU/L or 50 times the upper limit of normal, a rapid decrease of serum aminotransferase levels following the initial peak, an early rise in the serum LDH level and a ratio of ALT/LDH of <1.5 early in the course, thrombocytopenia, the absence of severe hyperbilirubineamia and an early increase of Cr, are rarely seen in other causes of hepatitis.3 8–10 The diagnosis of HH is usually based on the combination of the haemodynamic disturbance and the evidence of acute liver injury, and a liver biopsy is necessary in some cases.10 For this case, the liver biopsy and the MRI study were not attempted during hospitalisation because of the bleeding diathesis resulting from acute liver failure and acute renal failure, respectively. According to the literature, histological confirmation or imaging examination is not needed to confirm the diagnosis when there is a typical clinical course,4 which was described above. An outpatient MRI obtained 4 weeks after discharge showed mild cirrhotic change, which might be related to his chronic alcohol use.

A series of 14 patients with HH showed that cardiac diseases and ECG abnormalities are major predisposing factors of HH.10 During acute A-fib with RVR, the rapid HR and loss of effective atrial contraction could cause a marked decrease in cardiac output, especially in a patient with a pre-existing cardiac dysfunction.11 12 The episode of hypotension that developed suddenly during the intravenous diltiazem infusion might have caused further reduction in hepatic blood flow, which contributed to the development of HH. In this case, possible chronic congestion secondary to right heart dysfunction and alcohol-induced liver damage may have predisposed to the development of HH.

Intravenous diltiazem infusion has been widely used to control the ventricular rate during A-fib.13 14 Diltiazem is extensively metabolised in liver and one of the common side effects of diltiazem is hypotension. In the current case, the patient developed an unpredicted episode of hypotension 15 h after the initiation of the intravenous diltiazem infusion. Therefore, for patients with acute A-fib and underlying liver disease, closer BP monitoring is warranted during rate control using diltiazem.

Learning points.

In patients with underlying liver disease, even transient haemodynamical disturbances could cause hypoxic hepatitis.

Although hypotension most commonly occurs in the first few hours following initiation of intravenous diltiazem infusion, the patient presented in this case developed an unpredicted episode of hypotension 15 h later.

For patients with underlying liver diseases, closer blood pressure monitoring is needed during diltiazem infusion.

Acknowledgments

We thank Emanuela Verenca for editing the paper.

Footnotes

Contributors: WD collected and analysed the patient data, and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. LF supervised the information collection, data interpretation and manuscript preparation.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Henrion J. Hypoxic hepatitis: the point of view of the clinician. Acta Gastroenterol Belg 2007;2013:214–16 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birrer R, Takuda Y, Takara T. Hypoxic hepatopathy: pathophysiology and prognosis. Intern Med 2007;2013:1063–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seeto RK, Fenn B, Rockey DC. Ischemic hepatitis: clinical presentation and pathogenesis. Am J Med 2000;2013:109–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henrion J. Hypoxic hepatitis. Liver Int 2012;2013:1039–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henrion J, Schapira M, Luwaert R, et al. Hypoxic hepatitis: clinical and hemodynamic study in 142 consecutive cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 2003;2013:392–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen JA, Kaplan MM. Left-sided heart failure presenting as hepatitis. Gastroenterology 1978;2013:583–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nouel O, Henrion J, Bernuau J, et al. Fulminant hepatic failure due to transient circulatory failure in patients with chronic heart disease. Dig Dis Sci 1980;2013:49–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cassidy WM, Reynolds TB. Serum lactic dehydrogenase in the differential diagnosis of acute hepatocellular injury. J Clin Gastroenterol 1994;2013:118–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strassburg CP. Gastrointestinal disorders of the critically ill. Shock liver. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2003;2013:369–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Denis C, De KC, Bernuau J, et al. Acute hypoxic hepatitis (‘liver shock’): still a frequently overlooked cardiological diagnosis. Eur J Heart Fail 2004;2013:561–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prystowsky EN, Benson DW, Jr, Fuster V, et al. Management of patients with atrial fibrillation. A statement for healthcare professionals. From the Subcommittee on Electrocardiography and Electrophysiology, American Heart Association. Circulation 1996;2013:1262–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anter E, Jessup M, Callans DJ. Atrial fibrillation and heart failure: treatment considerations for a dual epidemic. Circulation 2009;2013:2516–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aronow WS. Management of atrial fibrillation in the elderly. Minerva Med 2009;2013:3–24 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aronow WS. Etiology, pathophysiology, and treatment of atrial fibrillation: part 1. Cardiol Rev 2008;2013:181–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]