Abstract

A 47-year-old woman was admitted to the emergency department with a history of asthenia, periorbital and lower limbs oedema, associated with hypokalaemia and increased blood pressure levels. Metabolic and renal causes were initially investigated as thyroid disease, Cushing syndrome and tubulopathies were excluded during the first week of admission. However, further questioning of the patient, revealed that she had been consuming several sachets of raw liquorice lollies (ignored amount) obtained from a herbalist a month ago. Based on the history and clinical findings, liquorice poisoning was highly suspected; an apparent mineralocorticoid excess secondary to ingestion of liquorice. Afterwards, levels of aldosterone and plasma renin activity were measured and found low 3 weeks later; therefore, our clinical suspicion was established. During the patient's stay at the hospital, liquorice was stopped and potassium supplements were started. Subsequently, a week after, the patient fully recovered without any significant sequelae.

Background

This case demonstrates the importance to investigate the patient’s lifestyle in detail, as part of the clinical history, as this may assist the early diagnosis of pseudohyperaldosteronism. In this particular case, large amounts of ingested liquorice led to poisoning, thus triggering hypokalaemia, which is rarely found these days. A high clinical suspicion is required in order to assess and treat this particular condition.

This case also demonstrates a high clinical suspicion of this condition by the emergency department.

Case presentation

A 47-year-old-woman presented to the emergency department with a history of fatigue, periorbital and lower limb oedema from the last 5 days. She denies any other symptoms. Physical examination showed blood pressure: 150/95 mm Hg, heart rate: 82 bpm, 96% SO2, basal temp 36.2°C, with periorbital oedema, ankles with pitting oedema (Godet Scale II), and the rest of the physical examination was unremarkable. However, during further questioning of the patient, she revealed that she had been consuming several sachets of raw liquorice lollies for the past 1 month.

Investigations

Haematology

WBC 6.24×109/L, haemoglobin 12.00 g/dL, haematocrit 34.80%, platelets 263 000×109/L.

Analytic

Glucose 79 mg/dL, urea 11.00 mg/dL, creatine 0.50 mg/dL; sodium 140 mmol/L, potassium 2.70 mmol/L, chloride 102 mmol/L, magnesium 1.9 mg/dL, bicarbonate 29 meq/L. Thyroid tests, hepatitis B and C, liver function tests, serum and urine cortisol; ACTH, and proBNP were within normal ranges.

Venous blood gases

PH: 7.43, PCO2: 45.6 mm Hg, HCO3: 29.9 mmol/L.

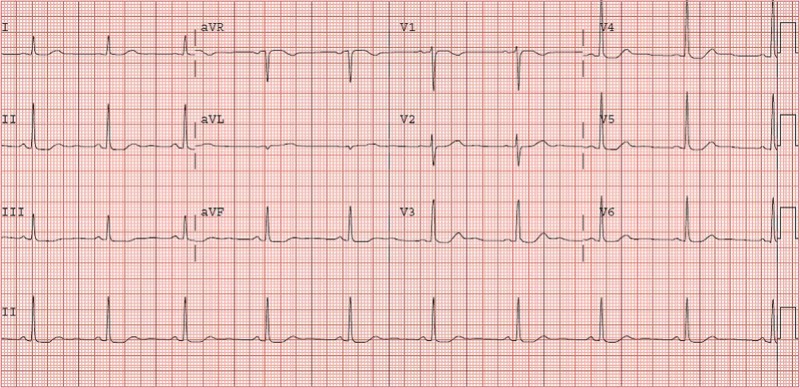

ECG

Presence of U waves (figure 1).

Figure 1.

ECG. U waves suggestive of hypokalaemia.

Urinalysis

pH 6.5, density 1007 g/L, protein negative, glucose negative, normal sediment.

Urine

Sodium 83.00 mmol/L, potassium 22.70 mmol/L, chloride 91.00 mmol/L, creatine 114.20 mg/dL, protein 0.178 g/L, glucose 0.140 g/L and osmolality 520.

Others

Aldosterone (Plasmatic): 40 pmol/L, plasma renin: 0.10 ng/mL/h.

Differential diagnoses

Primary aldosteronism

Heart failure

Treatment

Oral potassium supplements were instituted since the beginning with complete recovery in the third day (BOL-K 10 mEq 9 tablet/24 h). After diagnosis was made, liquorice lollies were immediately stopped. After a week, the patient recuperated completely and she was discharged from the hospital.

Outcome and follow-up

A month later, the patient was evaluated without any symptoms since her admission; potassium levels were within normal limits. The patient reported good general health since she stopped consuming liquorice products. Further renin and aldosterone levels were not requested due to the patient's significant clinical improvement.

Discussion

The traditional belief that liquorice is a healthy natural substance without side effects drives its abundant consumption which can occasionally be hazardous. Its main constituent, glycyrrhizic acid, mimics mineralocorticoids in its action (sodium reabsorption and potassium secretion). The extent of metabolic and acid–base derangement can occasionally be severe enough to cause serious complications.1

Chronic ingestion of liquorice or liquorice-like compounds induces a syndrome with findings similar to that in primary hyperaldosteronism, namely hypertension, hypokalaemia, metabolic alkalosis and low plasma renin activity. The only unique feature to this syndrome is that plasma aldosterone concentration is decreased.2–4

Liquorice-induced hypokalaemia is a rare condition; the most common symptom is generalised muscle weakness. Liquorice's active ingredient, glycyrrhizic acid inhibits, the 11 β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, which is responsible for conversion of cortisol to cortisone. As a result, renal mineralocorticoid receptors are activated by cortisol, which causes excess mineralocorticoid production. Glycyrrhetinic acid is the substance that causes hypertension and hypokalaemia.5

11-Hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase promotes the conversion of cortisol to cortisone, and one form of this enzyme (11 β-HSD2) is largely restricted in the kidney to the aldosterone-sensitive sites in the collecting tubules. This effect is physiologically important, because cortisol binds as avidly as aldosterone to the mineralocorticoid receptor.2 6

The World Health Organisation suggested that consumption of 100 mg/day would be unlikely to cause adverse effects. The Dutch Nutrition Information Bureau advised against daily glycyrrhizin consumption in excess of 200 mg/day.7 Liquorice overconsumption should be suspected clinically in patients presenting with the otherwise unexplained hypokalaemia and muscle weakness. A clue is provided when history reveals excessive dietary intake of liquorice, due to its aldosterone resembling effect.1

Together, the history of liquorice abuse, the low potassium, plasma renin and aldosterone levels, combined with the lowering of the hypertension and normalisation of the serum potassium after cessation of the liquorice abuse are sufficient evidence for the diagnosis of pseudohyperaldosteronism by liquorice abuse.5

Excess in the mineralocorticoid activity must initially be determined by the plasma renin activity and aldosterone levels. After determining the normal or low renin and aldosterone, the next step is to rule out other conditions that can cause an increase in the corticosteroid activity; this can be achieved by measuring cortisol levels and dexamethasone suppression test.8 9

The intracellular acidosis induced by hypokalaemia promotes increased secretion of hydrogen ions, which can react with luminal bicarbonate, leading to bicarbonate reclamation or to urinary buffers such as ammonia to produce ammonium. This increase in hydrogen ion secretion increases net bicarbonate reabsorption and can contribute to high levels of bicarbonate.10

Emergency physicians should enquire about liquorice consumption while taking the patient's clinical histories of unexplained hypertension, peripheral oedema or hypokalaemia. Although this patient's response to glycyrrhetinic acid spontaneously resolved, prompt physician recognition of this dietary habits may prevent the progression of toxicity in early-identified cases.11

Treatment involves removal and replacement of liquorice and consumption of daily potassium whereupon patients respond appropriately.12 13 Potassium replacement is primarily indicated when hypokalaemia is due to potassium loss like in this case. If the patient can take potassium supplements this is the pathway recommended, the urgency of therapy depends upon the severity of hypokalaemia, associated comorbidity, and the rate of decline in serum potassium concentration. In our case the cause was the liquorice intake and we considered oral replacement.10 This case contributes and adds relevant information to the previously reported cases of pseudohyperaldosteronism, due to the liquorice abuse.

Learning points.

Chronic ingestion of liquorice may resemble a clinical picture of primary aldosteronism; however, it differs from it by its low levels of aldosterone and plasmatic renin activity.

Early recognition of the clinical features of liquorice intoxication may prevent serious complications such as cardiac arrhythmias caused by hypokalaemia and rhabdomyolysis.

Pseudohyperaldosteronism by chronic ingestion of liquorice is a treatable condition; highly manageable with removal of products that caused such condition and by establishing potassium supplements immediately after confirming the diagnosis.

This case demonstrates that high clinical suspicion is required, in order to detect and treat this condition, from the first moment the patient is admitted to the emergency department.

Acknowledgments

Dr Cristina Vivanco, Dr Paula Molina.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Hesham RO, Komarova I, El-Ghonemy M, et al. Licorice abuse: time to send a warning message. Ther Adv in Endo and Metab 2012;2013:125–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kusano E. How to diagnose and treat a licorice-induced syndrome with findings similar to that of primary hyperaldosteronism. Intern Med 2004;2013:5–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Armanini D, Lewicka S, Pratesi C, et al. Further studies on the mechanism of the mineralocorticoid action of licorice in humans. J Endocrinol Invest 1996;2013:624–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sahay M, Sahay RK. Low rennin hypertension. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 2012;2013:728–39 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Janse A, van Iersel M, Hoefnagels WH, et al. The old lady who liked liquorice: hypertension due to chronic intoxication in a memory-impaired patient. Neth J Med 2005;2013:149–50 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farese RV Jr, Biglieri EG, Shackleton CH, et al. Licorice-duced hyperrmineralocorticoidism. N Engl J Med 1991;2013:1223–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sontia B, Mooney J, Gaudet L, et al. Pseudohyperaldosteronism, liquorice, and hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2008;2013:153–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moreno-Rodrigo A, Gutiérrez-Macías A, Arriola-Martínez P, et al. [Hipopotasemia asociada al consumo de regaliz.] Gac Med Bilbao 2008;2013:135–7 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moriés Alvarez MT. [Hiperaldosteronismo primario y secundario. Síndrome de exceso aparente de mineralocorticoides. Pseudohiperaldosteronismo. Otros trastornos por exceso de mineralocorticoides.] Medicine 2008;2013:976–85 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaplan NM, Young WF. Apparent mineralocorticoid excess syndromes (including chronic licorice ingestion). UpToDate, 8 Oct 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johns C. Glycyrrhizic acid toxicity caused by consumption of licorice candy cigars. CJEM 2009;2013:94–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saito T, Tsuboi Y, Fujisawa G, et al. An autopsy of licorice-induced hypokalemic rhabdomyolisis associated with acute renal failure. Nippon Jinzo Gakkai Shi 1994;2013:1308–14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meltem AC, Figen C, Nalan MA, et al. Hypokalemic muscular weakness after licorice ingestion: a case report. Cases J 2009;2013:8053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]